As an introduction, let me speak about how I lost my innocence as a starry-eyed art student in Kassel in 1959. The landscape architect Hermann Mattern had provided a setting for this event four years earlier by planting a new lawn and fields of roses, bushes to hide behind, and furnishing other amenities in the Karlsaue of Kassel. For the 1955 Bundesgartenschau he had been commissioned to transform this war-ravaged park, and the ruin of the Orangerie palace dominating it, into a new place of pleasure. It was the third time this publicly financed and hugely popular horticultural exhibition was held, each time in a different German city.

Mattern, in fact, had only prepared the grounds for my loss of naiveté. The real culprit was a certain Arnold Bode, a close friend and colleague of Mattern’s on the faculty of the academy in Kassel, where I was a student during the second half of the 1950s. With cunning and determination the two developed a scheme for adding an ambitious art component to the Bundesgartenschau. And they called it documenta.

As a professionally acclaimed landscape architect, Hermann Mattern had survived the Nazi regime relatively unscathed. Bode, on the other hand, had been fired from his job at an art teachers’ training college in Berlin soon after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933; and, according to the new terminology, being a ‘degenerate’ artist, he could not exhibit his paintings any more. In 1947, the two conspirators and like-minded friends resuscitated the Kasselart academy and made it an institution in the tradition of the Bauhaus. Studios, workshops, and an improvised lecture hall of what became my alma mater, were established in an old barracks building that had miraculously survived the war. That is where Bode and Mattern hatched the documenta plot in the early 1950s.

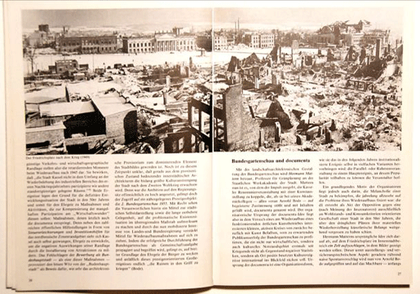

Fig.1

Kassel in Ruins 1949

Photograph reproduced in Kunstforum International, ed. Walter Grasskamp, vol.49, 1982, Cologne

Subtitle of issue (transl.): ‘Documenta Myth – A Picture Book for Art History’

Kassel was a major centre of Hitler’s military industrial complex and served as an administrative hub for the Nazis’ attempt to implement and export its brand of social engineering. In 1943, the city was subjected to devastating bombardments (fig.1). Its centre, like the heart of many German cities, was totally destroyed. Bode recognised the potential of one of the ruins, the Fridericianum, for accommodating the exhibition he was dreaming of. The Fridericianum had opened in 1779 as a public museum, the first museum built as such on the continent. Landgrave Frederick II of Hessen-Kassel had paid for it to house his art holdings, various other collections of his and a library. It offered him a naming opportunity: he called it ‘Fridericianum.’ The wherewithal for the collection and the place for its display came from the sale of some 30,000 of his subjects to King George III of England, who deployed these Hessian soldiers in the American War of Independence. As we know, without ultimate success.

Between the end of the Second World War and the reunification of Germany thirty-five years later,Kassel languished as an isolated backwater, far from major West German centres, about thirty kilometres away from the Iron Curtain. It was because of this precariousness that the Federal Government of West Germany and the state of Hesse provided considerable funds to the city, including finance for the 1955 Bundesgartenschau and – as its extension – a major international art exhibition. The rationale for these investments was similar to those behind the inclusion of a cultural component in World’s Fairs, the Olympic Games, the soccer World Cup and comparable events attracting visitors from around the world: urban development on a massive scale and building an up-to-date infrastructure. This combination of hard- and software, invariably, is meant to boost a city’s or a country’s image, with the expectation of reaping positive economic and political rewards. Be that Kassel, Londonor Beijing, the formula has proven its worth.

Pulling off the documenta scheme required shrewdness, political savvy, and a sense for the practical. Bode was endowed with all of these. At least as important, however, were his infectious enthusiasm and his almost naive and total commitment to a notion of art that had nothing to do with economic and political expediency. Aside from drawing a salary as a painting professor, he had earned extra money and acquired skills as the designer of trade fair interiors. This experience, and the connections made along the way, served him well in transforming the ruin of the Fridericianum into the site for what later was referred to as the ‘museum of 100 days’.

Of major historical significance for Germany – and perhaps beyond its borders – was the programme Bode and his collaborators developed for this improvised stage in downtown Kassel: nothing less than introducing or re-introducing Germans to the art which had been produced and exhibited in their own country before the Nazis banned it as ‘degenerate’, and acquainting them with developments in Europe, from which most had been cut off for almost two decades. In retrospect, it is difficult to fully appreciate the boldness and the need for such an endeavour – nor the consequences it has had.

It was the first documenta of 1955 and word that Fritz Winter, one of the best-known abstract painters in Germany at the time, had just been appointed to join the faculty, that made me apply for admission to the Kassel academy. I was accepted. Together with my fellow students, I was hired in 1959 to assist with the second documenta. We served as guards; and we moved works from one location to another until their position looked right to Bode and his team. And, even though we had no training other than what we had picked up during our studies, we led tours of even less informed visitors.

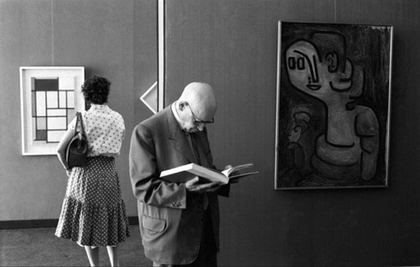

Fig.2

Hans Haacke

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Arnold Bode 1959

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

As sometimes bewildered or awed onlookers, we got a sense that this exhibition was not just an art event but had national and even international political implications (fig.2). As was to be expected, local dignitaries like the mayor of Kassel and the governor of the state of Hesse attended the opening. However, the president of the Republic came, too, as did cabinet members of the Federal government and ambassadors from many countries. As I learned later, the CIA had sponsored my first encounter with abstract expressionist paintings at documenta 2. Ironically, while having to fend off McCarthyite accusations against these works, it was the Museum of Modern Art’s International Council that sent them on a European tour to serve as weapons in the Cold War. In the fight over the hearts and minds of intellectuals on the continent, Kassel, close to the Iron Curtain, was to serve as a beacon of the ‘free world’ and contain the inroads so-called socialist realism had made in some European art circles (fig.3).

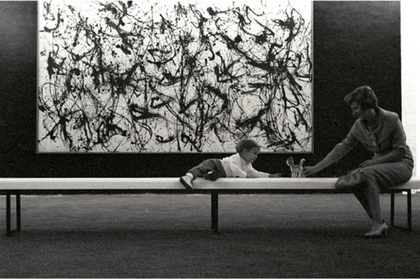

Fig.3

Hans Haacke

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Pollock Room 1959

© The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London 2009

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

As students of the academy in Kassel, we were aware of this Soviet art doctrine and its brutal enforcement not far from us to the east. We also understood that documenta played a role in another ideological struggle, this one home-grown: Hans Sedlmayr’s 1948 denunciation of much of nineteenth- and twentieth-century art and, in particular, of abstract art as a symptom of a ‘loss of the centre.’ 1 Sedlmayr, an Austrian Nazi collaborator, had succeeded not only in surviving the demise of Hitler’s ‘Reich of a Thousand Years’ but six years later in landing a senior position and a pulpit on the art history faculty of the University of Munich. Ingeniously, he had shifted his fascist ideological allegiances to the conservative wing of the Catholic Church. In art matters, this faction is most conspicuously represented today by Cardinal Meisner of Cologne (in 2007, during the debate over Gerhard Richter’s stained-glass windows in the Cologne Cathedral, the Cardinal warned his flock not to fall for ‘degenerate’ art). Sedlmayr met a hugely receptive audience and in 1955, the year of the first documenta, his polemic against modern art was re-published as a paperback by Ullstein, one of Germany’s biggest publishing houses.

One year before the first documenta in 1955, Painting in the 20th Century by the art historian Werner Haftmann was published in Munich.2 It was the first substantial overview of modern art after the war in Germany. In effect, it was a riposte to the philistine thesis of Hans Sedlmayr. Bode asked Haftmann to join his team and he became what commentators called the ‘chief ideologue’ of documenta. His impact in spreading the word on the art of the first half of the twentieth century and his personal bias of favouring the École de Paris and abstract painting cannot be overestimated. His selections for documenta, however, totally omitted dada, much of French surrealism, the works of Russian constructivists as well as paintings of Neue Sachlichkeit. Given the mindset of even the most open-minded art historians of the period it is not surprising that neither non-Western art nor photography was considered worthy of inclusion. The name of John Heartfield does not appear in the index of Haftmann’s book or in documenta. The phobia about Soviet-inspired art, coupled with the devastatingly costly triumph over the kitsch promoted by the Nazis, probably led to the exclusion of works that articulated political attitudes. Haftmann’s bible served as the only tool with which my peers and I tried to understand what we were guarding at the Fridericianum.

Fig.4

Hans Haacke

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Mondrian, Klee 1959

© DACS 2009

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

In effect, we also acted as stage-hands. A new term had entered the vocabulary associated with art presentations: Inszenierung or mise-en-scène, a term derived from the world of the theatre. Bode was the most accomplished among those who directed, or staged, exhibitions (fig.4). Mounting a show was not just putting one picture next to the other on the wall. Individualised spaces were set up for single or sets of works. The unusual structuring of juxtapositions or placement of works on facing walls, and vistas across adjoining spaces fostered dialogue between paintings. Fluid transitions between relatively open rooms produced an ambulatory experience, different from walking through the clearly circumscribed spaces of traditional museum architecture, or the tedious line-up of booths at trade fairs. Dominating visual axes were either avoided – or created to give leading roles to certain works in Bode’s and Haftmann’s choreography, as they did in the Fridericianum’s two commanding spaces on the second floor. One was dominated by a canvas approximately 250 cm by 650 cm by the German abstract painter Ernst Wilhelm Nay (fig.5). It was the largest painting in the show, no doubt boosting Nay’s reputation. The other space was devoted entirely to Pollock and presided over by his Number 32– in comparison to Nay’s painting, a rather small work (fig.6). Fontana’s slit canvases were relegated to the Fridericianum’s attic. I remember overhearing Werner Schmalenbach, one of the members of Bode’s team, insisting that Robert Rauschenberg’s Bed be removed. His wish was granted. Rudolf Zwirner, who served as secretary of documenta 2 kept the Bed in his office for the duration of the exhibition. Years later, Schmalenbach acquired Number 32 for the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, a new state museum he was heading by then, and Rudolf Zwirner became a powerhouse among German art dealers and co-founder of the Cologne Art Fair in 1967.

Fig.5

Hans Haacke

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Nay, Guided Tour 1959

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Fig.6

Hans Haacke

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Pollock, Child with Toy 1959

© The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London 2009

Photograph © Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

As I witnessed this particular moment of stage management, I overheard many conversations among art dealers, collectors, members of the press, as well as with the organisers of the exhibition – or behind their backs. Eventually, it began to dawn on me that documenta and, in fact, all exhibitions, by design or default, promote the ranking of artists and art movements as much as the prices for which their works are traded. Not only the selection and, for that matter, the omission of certain works from prestigious exhibitions has consequences: how they are presented, the attention they receive in the press, the business acumen of dealers and art advisers, but also the critical and art historical discourse surrounding them, can determine the reception of these works – and their market. Ignoring this inevitable aspect of exhibitions would yield a flawed comprehension of the dynamics of the art world; yet, to focus exclusively on the commodity status of art works or an artist’s celebrity rating among collectors, be that critically or in awe, would lead to an equally deficient understanding. After the loss of my innocence at documenta, I promised myself never to be dependent on the sale of my works to pay the rent.

Ten years after my graduation and five years after my move to New York, Kynaston McShine invited me to participate in the Information show he was curating in 1970 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was the first major exhibition of so-called conceptual art in the United States, after several European institutions had already introduced many of the artists to their audiences, among them Harald Szeemann in When Attitudes Become Form at the Berne Kunsthalle and the ICA in London (1969).

Two and a half months before the opening of Information, the USA invaded Cambodia and on 4 May, during a demonstration of students against the Vietnam War the Ohio National Guard killed four students at Kent State University. Practically all men of draft age were opposed to the war. Many went to Canada to evade the draft or tried to get a draft deferment by going to college (I had a number of such students at The Cooper Union in New York).

Several artists in the Information show were close to the Art Workers Coalition and Art Strike, two groups responding to the political events of the moment. They viewed the members of the boards of trustees of New York museums, in particular those of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum, as representatives of the ‘establishment’, responsible for the Vietnam War and the maintenance of racial, gender and economic inequality in theUSA. Heated confrontations occurred on the premises of MoMA and the Met. There were also rumblings by the staff of the Museum of Modern Art to form a labour union. It culminated in a strike against the museum’s administration the following year.

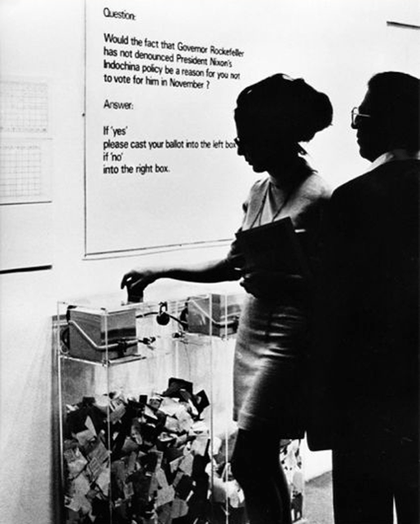

Fig.7

Hans Haacke

MoMA-Poll 1970

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

This was the context in which my MOMA Poll solicited the opinion of the visitors of the Information show on a topical issue (fig.7). The polling question referred to Nelson Rockefeller’s campaign for re-election as Governor of New York State. For many years, Henry Kissinger, who advised President Nixon on the US bombing of Cambodia and conduct of the so-called Cambodia Incursion had been Nelson Rockefeller’s trusted foreign policy consultant. Nelson Rockefeller had himself been president and chairman of the MoMA Board. His brother David was chairman at the time of the Information show and their sister-in-law was on the board as well.

I had not revealed the content of my question until the night before the opening. David Rockefeller was not amused. Word has it that an emissary of his arrived at the Museum the next day to demand the removal of the poll. However, John Hightower, who had just been appointed director of the Museum, did not follow orders. He lasted in his job less than two years.

In his Memoirs David Rockefeller offers his reasoning behind John Hightower’s short tenure:

He believed museums had an obligation to help society resolve its problems. Since Vietnam was one of the principal societal problems of the day, John thought MoMA should participate in the national debate … He allowed the bookshop to sell a poster of the infamous My Lai massacre … [Three members of the Art Workers Coalition had produced the poster.] This was followed by the infamous ‘information’ exhibition in the summer of 1970 … museum-goers were asked to vote on the question: ‘Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller had not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina policy be a reason for you not to vote for him in November’ … John was entitled to voice his opinions, but he had no right to turn the museum into a forum for antiwar activism and sexual liberation … Bill Paley [chairman of CBS and president of the MoMA Board], with my full support, fired Hightower in early 1972.3

Fig.8

Hans Haacke

MoMA-Poll (ballots) 1970

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

During its twelve-week run, the Information show had 299,057 visitors. 12.4 per cent of them participated in the poll (fig.8). 68.7 per cent dropped their ballots into the ‘No’ box, indicating their opposition to Nelson Rockefeller; and 37.3 per cent voted in his favour. It is not surprising that I became persona non grata at MoMA.

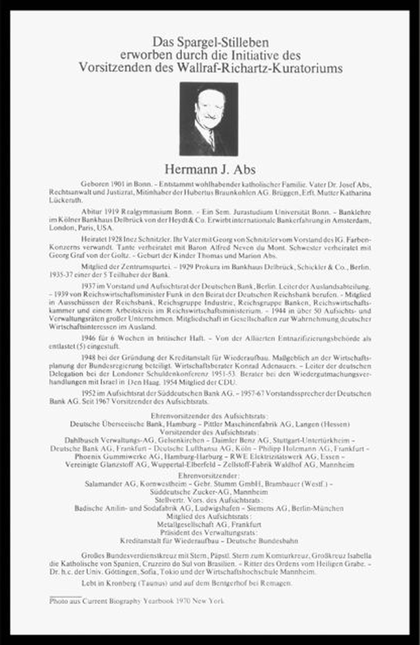

Fig.9

Hans Haacke

Manet-PROJEKT ’74 (Hermann J. Abs, one of ten panels) 1974

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

A few years later I also ran foul of the forces behind the Cologne Wallraf-Richartz Museum. I intended to include the biography of Hermann Josef Abs in the museum’s 150-year anniversary show (fig.9). As the chairman of Deutsche Bank he was a colleague of David Rockefeller. That was too much for the museum’s director in Cologne. Perhaps learning from what had happened to John Hightower, he censored the work. TheCologne museum is a municipal institution. MoMA, by contrast, is private. However, with its tax-exempt status and the tax-deductibility of donations by its patrons, the Museum of Modern Art is also supported by taxpayers.

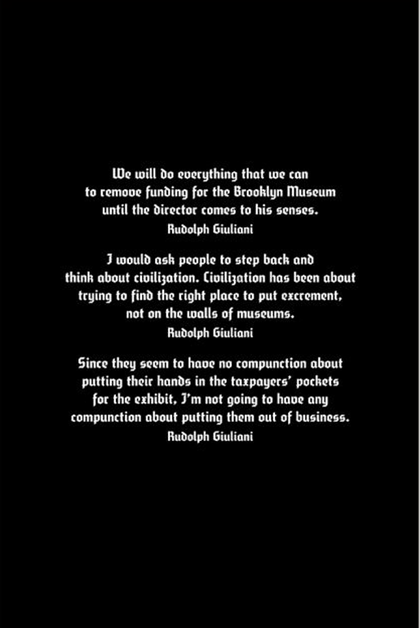

Today, David Rockefeller is still a force to reckon with at The Museum of Modern Art. In 2005 he pledged a donation of $100 million. Gratefully, the museum threw him a garden party. Two years earlier, Rudolph Giuliani had been honoured at such an event for his contribution to the arts in New York – after the mayor had tried to close down the Brooklyn Museum over its exhibition of works by Chris Ofili (fig.10). There is a tradition.

Fig.10

Hans Haacke

Sanitation (detail; quotes by Rudolph Giuliani) 2000

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

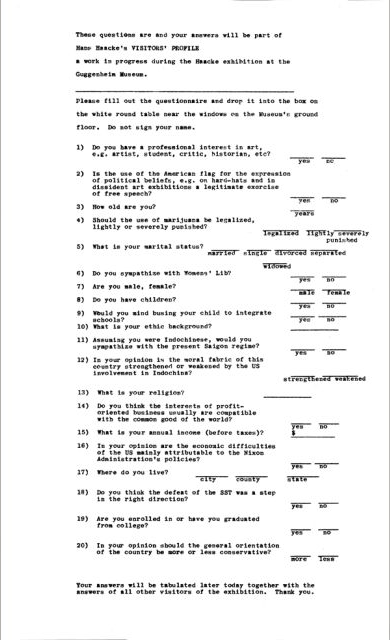

Fig.11

Hans Haacke

Guggenheim Museum Visitors’ Profile (unrealised questionnaire) 1971

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

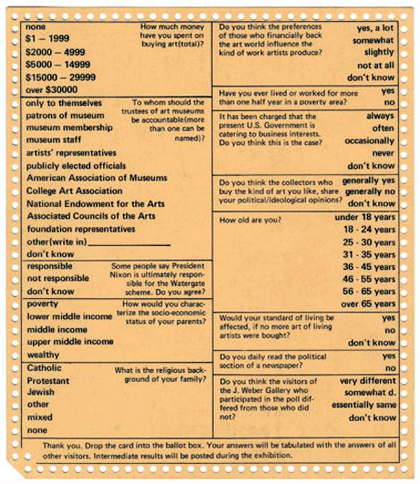

My interest in getting a sense of the public of art exhibitions began in 1969 with an inquiry into where the visitors of the Howard Wise Gallery on New York’s 57th Street were born and where they lived. In 1971, using a multiple-choice questionnaire, I planned to conduct an expanded poll of the visitors of a show that I was scheduled to have at the Guggenheim Museum (fig.11). As is well known, this exhibition was cancelled six weeks before it was to open. One of the three works the Museum director Thomas Messer objected to was this poll. It comprised ten demographic questions and ten questions concerning topical, political, and cultural issues. Messer argued the Museum ‘is non-political, is apolitical, and not concerned with political and social issues’ and therefore a political survey would be ‘out of bounds’. He saw it as his duty to prevent that ‘an alien substance enters the Museum organism’. I do not know whether the Guggenheim Museum in 1971 conducted audience surveys. Since then, however, the marketing department of every major museum in the world tries to learn as much as possible about its target audience.

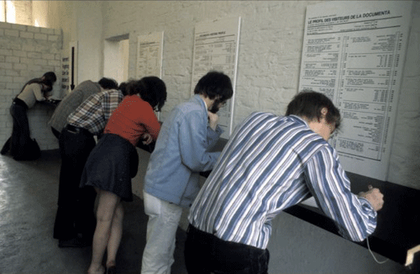

Fig.12

Hans Haacke

Documenta Besucher Profil (documenta visitors completing questionnaires) 1972

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

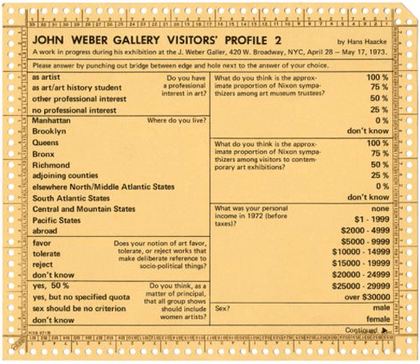

The questionnaire of the aborted Guggenheim poll served a few months later as a poll at the Milwaukee Art Center. And a year later, I took similar surveys of the audiences of the Krefeld Museum Haus Lange, Harald Szeemann’s documenta 5 (fig.12), the Kunstverein in Hanover, Germany, as well as the art crowd passing through the John Weber Gallery in New York (figs.13, 14). At that time, the John Weber Gallery was located in a building on West Broadway, together with four other galleries, among them the Castelli Gallery and the Sonnabend Gallery. The building was then known as the Pentagon of the art world. Of course, this concentration of galleries in one building inSoHo is nothing next to today’s art emporiums in Chelsea.

Hans Haacke

John Weber Gallery Visitor’s Profile 2 (questionnaire, side 2)

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Hans Haacke

John Weber Gallery Visitor’s Profile 2 (questionnaire, side 1) 1973

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Since the cumulative polling tallies were posted regularly in the exhibition, the visitors, in effect, were producing a collective self-portrait in a participatory and self-reflective process. I invited them to consider how much they have in common and how they differ from each other, and to speculate about how, collectively, their demographic composition and opinions compare with people who do not visit art galleries and museums exhibiting contemporary art. The data also offered the audience an opportunity to recognise that art is not produced, viewed and traded in an awe-inspiring world apart but in a continuous social universe.

In the early 1970s, a relatively large portion of the art audience was rather young; many were college students. The majority of the older respondents had at least a college education. Many of the young were living on a relatively low income, but appeared to come from at least a middle class if not well-to-do background. Since school classes were taken to documenta, a third of the participants of the documenta poll were high-school students. On both sides of the Atlantic, the visitors were almost uniformly white. At the height of the Vietnam War and a time of pervasive questioning of political structures, both in Europe and the USA, it is not surprising that a large number of respondents professed critical attitudes toward their governments and established institutions. But not only the young among the exhibition visitors, also their elders could be called liberals (in the American use of the term).

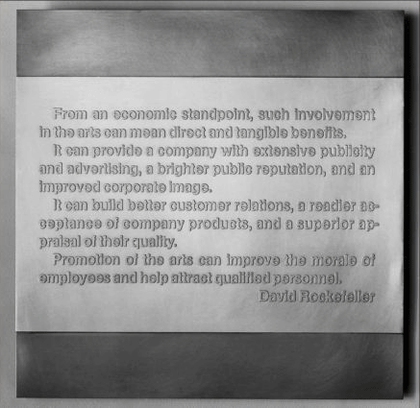

This audience belonged to that segment of society that was or could reasonably be expected in the future to be close to the decision-makers of the country, if not to occupy influential positions themselves. Corporations with foresight, in consultation with public relations experts, recognised that this group needed to be cultivated. As early as 1966, David Rockefeller, in his position as chairman of the Chase Manhattan Bank, had this to say: ‘From an economic standpoint, such involvement in the arts can mean direct and tangible benefits. It can provide a company with extensive publicity and advertising, a brighter public reputation, and an improved corporate image. It can build better customer relations, a readier acceptance of company products, and a superior appraisal of their quality. Promotion of the arts can improve the morale of employees and help attract qualified personnel.’ (fig.15)

Hans Haacke

On Social Grease (quote David Rockefeller; one of six panels) 1975

Photograph: Walter Russell

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

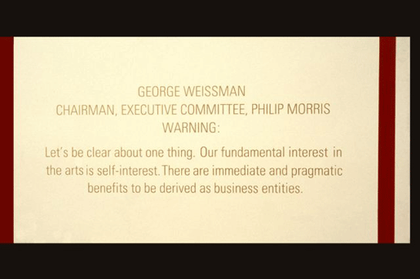

One of the early attempts to act on this understanding was, in 1968, the sponsorship by Philip Morris of Harald Szeemann’s When attitudes become form (fig.16). Ruder & Finn, aNew York public relations firm, guided the tobacco giant in this venture. In 2008, at the University of Venice, Claudia di Lecce wrote a thesis with the title ‘Avant-garde Marketing’ on this collaboration Under the heading ‘Arts & Culture’, Ruder & Finn currently tells the visitor of their website about what they are good at: ‘Our staff has experience in all of the following areas: institutional and corporate branding, identity and positioning; international and national media relations and special event management; sponsorship development and promotion; exhibition organization and circulation; strategic planning; and crisis communication.’4 Among their corporate clients (in the past) they list David Rockefeller’s Chase Manhattan Bank and Mobil.

Hans Haacke

Helmsboro Country (detail; quote by George Weissman) 1990

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

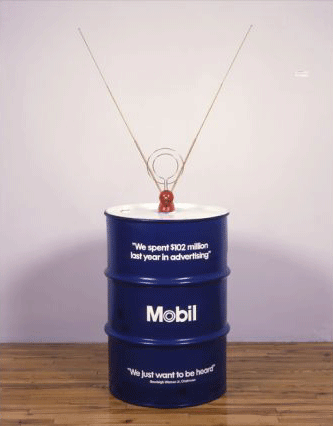

Since the 1970s, Mobil and Exxon (now merged) have been conspicuous sponsors of art exhibitions. In 1984 Mobil treated an exhibition of mine at the Tate Gallery to what Ruder & Finn elegantly calls ‘crisis communication’. It demanded that the catalogue of the show be taken out of circulation. Supposedly, I had violated Mobil’s copyright in several of my works (fig.17). For almost an entire year the Tate Gallery did, in fact, pull the catalogue. It was released only after a big New York law firm explained to the Tate that Mobil had peddled a bogus interpretation of US law. Under the so-called fair-use doctrine, my use of the company’s logo and quotes from its public pronouncements are exempt from copyright protection. Of course, they did not quite conform to the notion of ‘Art, for the sake of business’, as Mobil had proclaimed in an advertisement on the Op-Ed page of the New York Times. For the dense reader of this ad the sponsors offered this reasoning: ‘What’s in it for us – or for your company? Improving – and securing the business climate.’

Fig.17

Hans Haacke

Creating Consent 1981

Photograph: Fred Scruton

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Six years later, Philip Morris (now sailing under the name of Altria) did not appreciate my interpretation of ‘innovation’ and ‘experimentation’ that the company had claimed when it sponsored Harald Szeemann’s Berne exhibition. John Weber got a letter from Philip Morris’s counsel, warning him that the company would react negatively if his gallery were to go ahead with an exhibition of mine that revealed the tobacco company’s sponsorship of Senator Jesse Helms – as one could deduce from the show’s announcement Helms had made himself a name as the most powerful culture warrior of his time. Fortunately, John Weber was not intimidated. The show went on (fig.18).

Fig.18

Hans Haacke

Helmsboro Country 1990

Photograph: Fred Scruton

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

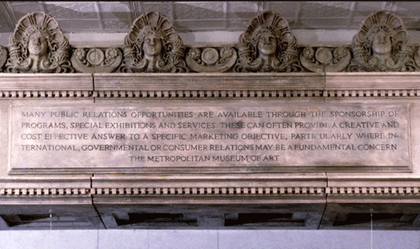

My citing these examples risks being understood as petty attempts to get even over minor slights, and overlooking the dependency of so many museums and art venues on corporate support. Therefore I like to quote an expert, Philippe de Montebello, the former director of the MetropolitanMuseum. In 1985 he confided to Newsweek: ‘It’s an inherent, insidious, hidden form of censorship.’ He probably meant self-censorship. Exhibition projects that are not likely to attract crowds, or could cause damaging controversies within the sponsors’ target group, are abandoned before the institution even looks for outside funding. Curators have internalised these rules of the game and, understandably, do not want to waste their time. The corporations’ largesse, of course, is tax-deductible (fig.19).

Fig.19

Hans Haacke

MetroMobiltan Detail (quote from Metropolitan Museum flyer The Business of Art knows the Art of Good Business) 1985

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Documenta in its early days attracted a mere 135,000 visitors, and Harald Szeemann’s instalment in 1972 increased attendance to approximately 230,000. These are paltry figures. Art audiences have since grown exponentially – as has the size of museum gift shops. Blockbuster exhibitions are de rigueur. Even the former stepchild, contemporary art, has become glamorous, in part due to a new breed of turbo collectors and multi-million dollar price tags. Accelerating and banking on this development, the fashion industry has moved in. Major fashion houses have joined the club of sponsors courted by museums, curators, and an increasing number of artists. The rag trade emulates the example of oil companies, high-end car manufacturers and banks, whose PR departments had recognised decades ago how an association with culture could improve their image and sales, and make them immune to critical questioning of their business practices. Already in Kassel, a hunch that documenta might attract hotel guests to this godforsaken city and fill restaurants and bars, encouraged the expenditure of tax money. Today, it is generally understood that the tourist and entertainment industry benefits from big art exhibitions. This year, the mayor ofNew York appointed theMetropolitanMuseum’s President Emily Rafferty to chair the board of NYC & Company, the city’s marketing and tourism organisation.

Fig.20

Bust of Riccardo Selvatico, Mayor of Venice, Giardini Pubblici, Biennale Site, Venice

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

As early as 1895, well before documenta, Riccardo Selvatico, the mayor of Venice (fig.20), invented an art fair to promote the artists in town and to boost the local tourist industry. The then dominant nations of Europe took an interest in his venture. France, Britain, and Germany joined. Each built a national pavilion and hoisted their flags on a hill in the Giardini Pubblici, a hill, which had been created from the rubble of the campanile of San Marco after its collapse in 1902. Other nations followed in the lowlands. It became the mother of all biennials.

Fig.21

Hans Haacke

GERMANIA 1993. Entrance to German Pavilion, Venice Bienniale

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Commissioner of the German pavilion for the 1993 instalment of the Venice Biennale was Klaus Bussmann, at the time the director of the Westfälisches Landesmuseum and known as the co-founder of Skulptur-Projekte Münster. The pavilion is owned by the German government and administered by its Foreign Office (fig.21). Government officials urged Bussmann to select an East German and a West German artist, now that the two parts of Germany were reunited. In his view, this smacked of nationalism. And he resented the meddling in his selection process. In response, he asked Nam June Paik and me to occupy the site on the hill. Paik was Korean, and I had been living in New York since 1965 and had not made myself popular among officials of my native country.

After some soul-searching, I accepted Bussmann’s invitation. I decided to represent Germany in both senses of the term: being the official representative of Germany – the flag bearer, so to speak – and producing a representation of the country. Preparing for this task, I researched the pavilion’s history, and, for hours, sat alone in its nave which had been assigned to me.

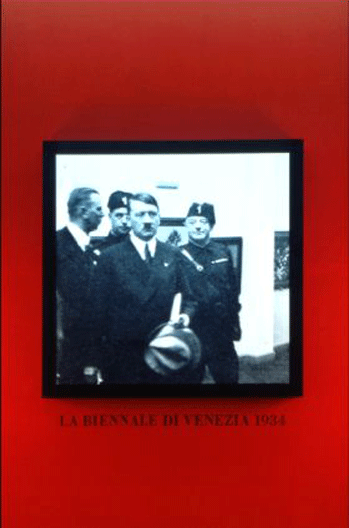

Fig.22

Hans Haacke

GERMANIA (detail) 1993

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

I learned that the pavilion’s present appearance was tied to Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. As part of an excursion to Venicefor a meeting with his comrade Benito Mussolini, the man who had not succeeded as a painter in Vienna, paid a visit to the Biennale and the German pavilion (fig.22). Hitler did not like what he saw. As a consequence, by 1937 an exhibition titled Degenerate Artopened inMunich, and plans for the re-styling of the pavilion inVenice were approved. A new national corporate identity was in the making – and so were preparations for the expansion ofGermany beyond its borders and the introduction of a deadly programme of ethnic cleansing.

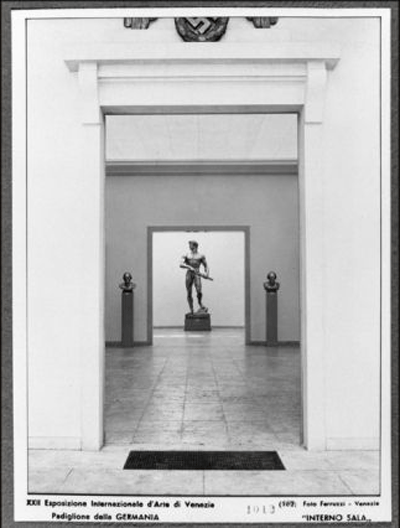

Fig.23

Entrance to German Pavilion, Venice Bienniale, 1940

(Arno Breker, Readiness 1939)

© Biennale Archives, Venice

Hitler’s invasion of Poland and, as a consequence, the beginning of the Second World War, was accompanied by Arno Breker’s occupation of the German pavilion in the Giardini Pubblici, in 1939 (fig.23). For the occasion, Paik’s and my predecessor presented to the international art world a body builder drawing his sword. The title of his statue was Readiness. A lot had happened since. Fifty years later, with the reunification ofGermany, a significant step could be taken to repair at least some of the horrific damage of the proclaimed ‘readiness’. As we all know, the human toll of these years could not be undone.

Fig.24

Hans Haacke

GERMANIA 1993

Photograph: Roman Mensing

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

I had not anticipated that the rubble of the marble plates (fig.24), with which Hitler’s architect had replaced the pavilion’s original parquet floor, would make some viewers think of Caspar David Friedrich’s 1823–4 Shipwreck of Hope, now at the Hamburg Kunsthalle. The painting has been interpreted as expressing Friedrich’s despair over the central European monarchies’ successful repression of the Republican movements and of the democratic agitation that had been inspired by the French Revolution and was followed by victory in the wars of liberation against Napoleon. The fact that the masts of the ship caught in the ice look like the trunks of fir trees with stumps of cut off branches encourages me to accept this interpretation. Friedrich is known for encoding political symbols in his paintings. To him fir trees representedGermany. I observed how visitors of the field of rubble in the German pavilion picked up unbroken plates and, with obvious emotion, smashed them to bits. Children used it as an adventure playground.

My works have been presented in a number of documentas and biennials. Some of these spectaculars may be traded under the heading ‘landmark exhibitions’. What qualifies as such, of course, is fungible. The most recent Biennial including works of mine was the Gwangju Biennial inKorea, which opened in early September 2008.

Like documenta, the Johannesburg Biennial and the Gwangju Biennale – respectively, the first biennials inAfrica and inAsia, and both founded in 1995 – have political origins. In Johannesburg, it marked the cultural opening after apartheid. Less known is the story behind the Gwangju Biennale. Gwangju, about two hours south of Seoul, was distant or in outright opposition to the eighteen-year reign of the South Korean dictator Park Chung-hee and his equally dictatorial successor. In May 1980, an uprising, spearheaded by local students and professors, was brutally suppressed by the military. Many hundreds of demonstrators were massacred (fig.25). In 1995, a few years after a democratically elected president was inaugurated inSeoul, the Gwangju Biennale was founded as part of the retrospective celebration of the democratic uprising and a commemoration of its martyrs.

Fig.25

Hans Haacke

National Cemetery at outskirts of Gwangju, where the victims of 18 May 1980 uprising against the South Korean dictatorship are buried.

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

In his foreword to the Biennale catalogue, the city’s mayor, who is also the President of the Gwangju Biennale Foundation, said: ‘the Gwangju Biennale belongs to civil society on the one hand, and on the other, it is a public and communal product of the co-operation among cultural agents, artists, economists and the city of Gwangju … These efforts will no doubt cohere positioning Gwangju as a strategic signpost on the road to becoming the cultural hub-city of the global village and the cultural capital of Asia.’5 Both the city of 1.3 million and theSeoul government appear ready to provide the funds for such an enterprise. Aside from the aspect of political restitution, they recognise the potentially profitable conversion of the symbolic capital of Gwangju into economic capital, with which they hope to secure the city’s future as ‘the cultural capital ofAsia’ (fig.26). Conversions of the symbolic capital of art works into economic capital have always been the raison d’être of the art market, too.

Fig.26

Hans Haacke

Promotion of Gwangju as ‘Culture Hub City of Asia’ (municipal building, Gwangju) 2008

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Okwui Enwezor, who had curated the 2nd Johannesburg Biennial in 1997 and documenta in 2002, was appointed artistic director of this year’s Gwangju Biennale. The encounter with works in galleries – i.e. in art trading posts – has always had an effect on selections for ostensibly non-commercial presentations. Okwui Enwezor (fig.27) openly put his Biennale under the headingAnnual Report. He invites the reader of the bilingual catalogue to follow A Year in Exhibitions, presenting on sixty pages the press releases of the galleries and not-for-profit venues visited. He and his co-curators Hyunjin Kim of Korea and Ranjit Hoskote from India, and the four authors of so-called ‘Position Papers’ and ‘Insertions,’ based in Korea, the Philippines, Morocco, and New Orleans, selected works from around the world. None of the artists and groups chosen can be considered big players in the contemporary art market. A great number are not fromWestern Europe or theUSA. Probably for that reason, the majority was unknown to me. In many instances, I had difficulty in getting a sense of the meaning of their works, because I knew little or nothing about the context in which and for which they had been made. It was challenging, and I learned a lot.

Fig.27

Hans Haacke

Okwui Enwezor, Commissioner of Gwangju Biennial 2008

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

The Gwangju Biennial attracted 400,000 visitors this year – most of them from the region, and among those a great number were school classes. Last year’s documenta had 750,000 visitors. Also in Kassel a great many were high-school students under the guidance of a teacher. It would be worth exploring what either public made of the works it was exposed to. I am certain, however, that the exposure to these exhibitions will affect their sense of themselves and of the world they live in. Such experiences have the potential of contributing to the social consensus of a period and a country.

Fig.29

Hans Haacke

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Cleaning Women (Hans Haacke) 1959

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Fig.29

Hans Haacke

Wide White Flow 1967 (installation at Gwangju Biennial 2008)

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

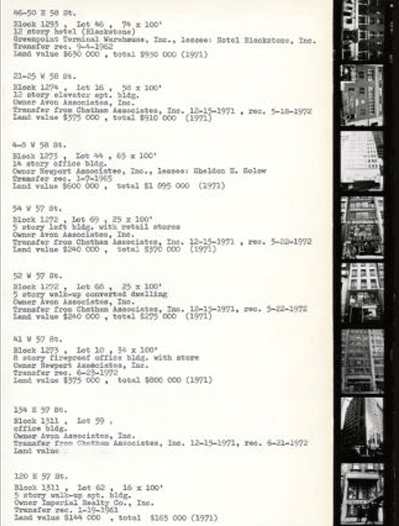

In January 2008, Okwui Enwezor saw an exhibition of mine at the Paula Cooper Gallery in New York. He decided to make the entire show part of his Annual Report. To be seen in Gwangju were five works from the show: photographs that I had taken at documenta in 1959 (fig.28), Wide White Flow, an installation with moving parts from the 1960s (fig.29), one of the three works that cost me the solo show at the Guggenheim Museum (fig.30), and two works offering a sense of my feelings about current US politics, Trickle Up (figs.31, 32) and Mission Accomplished (fig.33) The most recent is a torn image of the stars in heaven and the American Flag on earth (fig.34).

Fig.30

Hans Haacke

Sol Goldman and Alex DiLorenzo Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, 1971 (detail)

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Fig.31

Hans Haacke

Trickle Up 1992 (as shown at Gwangju Biennial 2008)

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Fig.32

Hans Haacke

Mission Accomplished 2005 (detail, on wall, as exhibited at Gwangju Biennial 2008)

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst

Fig.33

Hans Haacke

Mission Accomplished 2005 (detail, on floor, as exhibited at Gwangju Biennial 2008)

© Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst