Daniel Buren, Travail in situ, Wide White Space Gallery, Antwerp, June 1971

The young French artist, Daniel Buren, is internationally known for an artistic production that questions all the usual concepts about what is fundamental in art. At the Sixth International Exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, his work was almost universally boycotted by the masters of the contemporary avant-garde. Daniel Buren has also written extensively and very theoretically about his work, about which people are able to say very little at first sight. It always repeats the same simple pattern.

These are the first sentences spoken in a short film produced by the Belgian Dutch-language public broadcasting company BRT, shown on television on 22 May 1971, at the time of Daniel Buren’s second exhibition at the Wide White Space Gallery in Antwerp (Travail in situ, 11 May–5 June 1971). The film, lasting only five minutes and forty seconds, is by Jef Cornelis, and was made for Zoeklicht op de culturele actualiteit (Spotlight on Current Cultural Events), a short, prime-time news programme first broadcast in 1969 and aired six days a week by what was then Belgian Radio and Television.

This untitled short film seems at first relatively conventional. The Wide White Space Gallery comes into view, while the artist concerned is introduced offscreen. Then a ‘reporter’,1 Georges Adé, throws a number of critical queries to the artist: ‘You always repeat the same thing. In what way does this represent a rupture?’ ‘Do you believe in [the development or so-called progress of artists and art]?’ and ‘Do you sell this thing?’ The questions are critical but pose no threat to an artist known to be exceptionally articulate.

The film is nonetheless essentially discordant in nature. In the four short opening sentences spoken by an offscreen female presenter, reference is made to one of the biggest conflicts in which Buren had been involved during his long career. This was the commotion caused by his contribution to the Sixth Guggenheim International Exhibition in 1971, the same year the film was aired on the Zoeklicht programme. The French artist had been given the green light by the Guggenheim in October of 1970 for his two-part project – a work for a public space, made of paper, and a giant canvas to be hung in the large central space of the Guggenheim. Once the canvas had been hung, curator Diane Waldman gave in to pressure from two American artists, Donald Judd and Dan Flavin, who insisted that Buren’s work be removed.

Although only four sentences are devoted to introducing Buren, Cornelis chose to cite this exhibition at which the French artist was ‘almost universally boycotted by the masters of the contemporary avant-garde’. The first thing said in the film is that Buren’s work questions ‘what is fundamental in art’. This is illustrated by the reference to the conflict that had occurred in the Guggenheim Museum. In addition to evoking this literal or real conflict – which I believe has to do with Cornelis’s own interest in conflict as such – there is another important moment in the film. Unlike the introduction by an offscreen commentator, Adé’s mildly incisive questions, or Buren’s razor-sharp answers, what takes place now is non-verbal. In order to examine what actually happens in the film, it is important first to take a look at Travail in situ, the work that Buren was showing at the Wide White Space Gallery.

As the title of the work indicates, Travail in situ was made on location, at the Wide White Space Gallery, located in Schildersstraat in Antwerp. The work existed only for the duration of the exhibition (11 May–5 June 1971). For this period, Buren attached posters to the lower section of the outside and inside walls of the Wide White Space Gallery. On one side of the poster was information about the exhibition, the address of the gallery, dates and other practical details. The other side was printed with alternating red and white stripes, 8.7 centimetres wide. The posters were lined up perfectly one against the other, creating a long band of stripes that ran from the outside of the gallery, over the front door, to the inside (fig.1). There was nothing else in the gallery space, apart from the partially covered lower wall. In other words, the Wide White Space Gallery’s regular visitors had received an invitation to go see a work that was made up of – and nothing but – the invitation itself.

Fig.1

Jef Cornelis

Still from an untitled film made for Zoeklicht op de culturele actualiteit 1971

© Courtesy Argos, Brussels

Travail in situ was not Buren’s first gallery exhibition. In 1968, he had worked with the Galleria Apollinaire in Milan, where he hermetically sealed the glass door, the only entrance to the gallery, with striped paper. Following his contribution to Prospekt in Düsseldorf that same year, for which he had been selected by Guido Le Noci from Galleria Apollinaire, he received various invitations from galleries, including the Wide White Space Gallery, where in 1969 Buren presented the same work that he later showed in 1971. Only the colour of the stripes – selected in both cases by Anny De Decker, owner of Wide White Space, with the support of her husband, Bernd Lohaus – was different: in 1969, De Decker and Lohaus chose green, the same colour as the work that Buren had made for Prospekt; in 1971 they chose red.

Both Cornelis and Adé had met Buren for the first time on 24 May 1969, when they were involved in the founding of the A379089 alternative art space, named after the telephone number of the space on the Beeldhouwersstraat in Antwerp, a stone’s throw from the Schildersstraat where the Wide White Space Gallery was located. A379089, run by the German curator Kasper König, was destined to be short-lived (it lasted a mere ten months), but in that short period it was the scene of a number of exceptional events, including the opening of Marcel Broodthaers’s Musée d’art moderne, Département des Aigles, Section XVIIème Siècle, the performance This is the Ghost of James Lee Byars Calling, and La Monte Young’s and Marian Zazeela’s environment A Continuous Environment in Sound and Light with Singing from Time to Time. Another of König’s initiatives was the re-publication of Mise en garde, Buren’s critical pamphlet that had been published only a few months before in the catalogue to the exhibition Konzeption: Dokumentation einer heutigen Kunstrichtung, organised by Rolf Wedewer at the Schloss Morsbroich Municipal Museum in Leverkusen.2

Thus, Cornelis and Adé, both of whom contributed financially and logistically to the activities of A379089, had known Buren back in 1969 and were familiar with the artist’s critical discourse. They may also have seen Buren’s first version of Travail in situ at the Wide White Space Gallery. Adé’s questions, especially ‘In what way does this represent a rupture?’ and ‘Do you believe in [the development or so-called progress of artists and art]?’, would suggest that he had read Mise en garde. In that text Buren claimed that the so-called avant-gardes never express themselves in more than fictitious or illusory ‘breaks’, while in fact, a real break – a rupture – needs to be produced. Adé’s questions were an almost literal paraphrasing of Buren’s claims in Mise en garde. Although they appear to be aggressively critical, they offered the artist an opportunity to elaborate on his position.

After his 1969 and 1971 exhibitions, Buren would be invited back to the Wide White Space Gallery three more times, in June 1972, June 1973 and April 1974. In each case he produced the same work, using different colours for each exhibition: yellow in 1972, blue in 1973 and brown in 1974. Buren took his own photographs of all of these variations of Travail in situ and, as he always did, referred to these photographs as Photos-souvenirs. All of these Photos-souvenirs were subsequently published in the 1990 catalogue A chaque monstration sa place – Travaux 1966–1989, produced by the Isy Brachot Gallery in Brussels on the occasion of an exhibition by Buren. The catalogue shows that Buren took one photograph from the outside of the gallery and one from the inside, each taken from virtually the same vantage point. The snapshots were thus thoughtfully produced, and their reproduction in A chaque monstration sa place makes direct comparisons between them possible, a virtual spot-the-difference. An overview of the Photos-souvenirs reveals that in the photographs of the outside of the gallery, the double front door is sometimes closed (1969, 1972, 1973), and sometimes open (1971, 1974). However, in the photographs of the interior of the gallery, one section of the double door is always open, so that the viewer can see that the band of stripes runs over a portion of the front door, from inside to outside and vice versa.

If we compare the Photos-souvenirs with the way Cornelis filmed Travail in situ in 1971, one essential difference immediately becomes apparent. In the Photos-souvenirs, there are virtually no passers-by, except for the single proverbial exception, at the far left of a photograph from April 1974. In Cornelis’s short film, by contrast, there are no fewer than twenty-three passers-by, of whom only two are seen more than once – that is, twenty-one different people in a film lasting barely more than five and a half minutes. In this count, I confess to having included a dog, which makes its appearance in the company of a woman five minutes into the film. While this may sound trivial, I think it is important, and will return to this below.

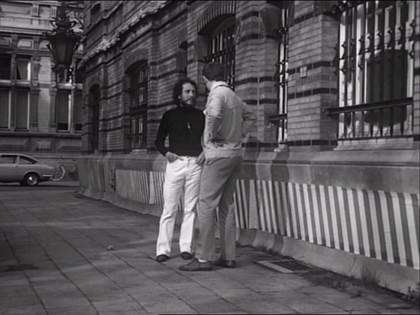

Does the busy pedestrian traffic along the Schildersstraat in Antwerp, where the Wide White Space was located, hold any particular meaning? That is to say, is there some significance in the fact that these people are in the image or is it pure coincidence? To answer these questions, we need to look at how the figures come into the image. The film begins with an overhead shot of the impressive building in which the gallery was housed. This is not just the highest shot of the film, but also the most impressive: the beautiful Art Nouveau building is shown in its entirety, making it almost impossible to see Buren’s work. Three passers-by appear in this image. In addition, the film includes five other kinds of shot, not counting the travelling shot over the invitational poster at the end of the film and the final credits. These shots include a fairly high shot of the building, in which Buren’s work is clearly visible; close-ups of Buren’s work, in which the pavement is prominent; a travelling shot moving from inside to outside the gallery; a shot of Buren and Adé standing in front of Buren’s work, both men in full frame (fig.2); and a close-up of Buren. There are passers-by in each of these frames, except for the travelling shot where the camera scans the work at such close range that it would have been impossible for any figures to be included.

Fig.2

Jef Cornelis

Still from an untitled film made for Zoeklicht op de culturele actualiteit 1971

© Courtesy Argos, Brussels

In itself, the fact that all the other shots include people is remarkable; even in the close-ups passers-by manage to find their way between the camera and the artist. To ascertain whether or not the presence of these passers-by is purely coincidental, let us look at the fragments of the film in which the commentator’s voice or Adé’s conversation with Buren is heard, without the speakers being in view. It is in these fragments that most of the passers-by appear. There are, however, major differences in the sequences. In the first, filmed from a very high vantage point, the people are necessarily extremely small, like toy soldiers. In the second group, in which the whole of Travail in situ is in view, people walk past Buren’s artwork: some simply walk past the open door of the gallery, while others – identifiable as De Decker’s and Lohaus’s children, the latter’s nanny and possibly De Decker and Lohaus themselves – walk in and out the door. A third group of sequences makes clear that the filming of the pedestrian traffic along Buren’s work is anything but coincidental. These are the sequences in which only part of Buren’s work is in view, along with part of the pavement outside the gallery.

This last sequence is edited over the soundtrack, starting when the figure(s) step into view. The camera then tracks the figure(s) through their entire trajectory along Buren’s work, following their every step. Eight people appear in the film in this way, and two conclusions can be drawn from their appearance. The first argues in favour of a conscious decision to show a representative sample of society – including both men and women, young and old. The second conclusion concerns the way in which the passers-by appear. In only one of the fragments can an individual’s face be seen. This is a shot following two girls in mini-skirts, carrying handbags and engaged in conversation, as they walk right past Buren’s work. It is clear that they have not seen the art work. In all the other shots, the heads of the passers-by are outside the frame, or are filmed from behind, making it impossible to determine whether they have noticed Buren’s work or not. We do know, however, that they did not stop to contemplate the work. Indeed, everyone who walks by does just that: simply walk right past the work. (Everyone, that is, except the small child of the gallery owners, poking at one of the paper stripes in Buren’s installation, and who is quickly removed from the scene of his or her crime by a parent or nanny.)

Fig.3

Jef Cornelis

Still from an untitled film made for Zoeklicht op de culturele actualiteit 1971

© Courtesy Argos, Brussels

To sum up, there is a lot of activity in the vicinity of Buren’s work but no interest in it whatsoever. The film seems keen to show that the passers-by apparently have no interest in the French artist’s work. This intention is most obvious when the woman with the dog – and not just any dog, a poodle, a typically upper-class status symbol – appears in the image, at the exact moment when an embarrassed and bewildered Adé asks, pointing to Buren’s paper stripes: ‘By the way, do you sell this thing?’ (fig.3) Buren had just finished saying, ‘it’s a painting that is seen twice, which raises the specific problem of paintings, which are generally seen once.’ Adé had understood Buren as saying ‘vend’ instead of ‘voit’, ‘sell’ instead of ‘see’.3 As soon as Adé asks this question, the lady with the poodle makes her entrance in the film. Any image that Cornelis might have edited over this section of the soundtrack would have produced the same kind of answer – ‘No, I am not interested. I do not even notice this art work. How could I possibly be interested in buying it?’ – but by including a lady walking down the street behind a poodle, both perfectly oblivious to Buren’s work for sale on the wall, Cornelis is emphasising the public’s indifference to contemporary art to the point of caricature.

Cornelis is not only fascinated by the critical discourse expressed in Buren’s Mise en garde and by the conflicts generated by the work – the dispute, for example, about the artist’s work at the Guggenheim. The filmmaker also managed to stage his own conflicts, as exemplified by the silent, critical commentary of the woman and her poodle in response to Adé’s confused question ‘Do you sell this thing?’ Sitting at the editing table, Cornelis inserted the film sequence of the lady and her poodle at the very spot where Adé and Buren refer to the work being for sale: an intentional superimposition, I would argue, that was meant to support the film’s layered critical commentary.

Sonsbeek buiten de perken, Arnhem, June-August 1971

It is no exaggeration to say that at least a portion of Cornelis’s oeuvre, especially his films devoted to art exhibitions between 1968 and 1972, constitutes a collection of conflicts. These conflicts were sometimes obvious, as in Cornelis’s 1968 film on documenta 4, in which French artists, including Martial Raysse, criticise the exhibition. In his film on the next documenta, in 1972, Cornelis focused on the standpoints of different representatives of so-called conceptual art, including Lawrence Weiner and Joseph Kosuth. These two examples suffice to demonstrate that Cornelis possessed a kind of sixth sense for art-world conflicts – between artists and curators, amongst the artists themselves and between critics and curators.

Another film from 1971, the same year as the short film on Buren, offers additional material in support of this thesis. It is Cornelis’s film on that year’s Sonsbeek exhibition (Sonsbeek buiten de perken, or Sonsbeek Out of Bounds), held between 18 June and 15 August. In this longer work, which runs forty-seven minutes and fifty seconds, the various protagonists seem literally to fight their way through the film. Before introducing the actors themselves, however, we should first pause at the highly original way that Sonsbeek buiten de perken was officially opened on 18 June on the Dutch national television evening news. ‘In a few minutes, live from Arnhem, the art event Sonsbeek buiten de perken will begin’ is how the newsreader presented the experimental exhibition to Dutch television viewers. He went on:

In addition to Sonsbeek Park itself, at a large number of locations across the country, art is being shown in a new way. The organisers have taken one important thing into account: teaching people to look, compelling people to look, often at ordinary, everyday things, or at something that is really bizarre, or maybe just something that you might find beautiful. The Sonsbeek people consider communication to be very important. For that reason, there is a tent, rather like a molehill, where you can have a discussion with other people in other parts of the country, by telephone or by Telex.

Following this statement, several participating projects were introduced, including Ger van Elk’s work at the Tropical Museum in Amsterdam, a bed of Salvia plants by Fred Sandback at Sonsbeek Park and Robert Smithson’s Broken Circle outside the city of Emmen. The newsreader concluded: ‘It will all continue until 15 August. The Sonsbeek buiten de perken exhibition will begin five seconds from now.’ Meanwhile, Cornelis and Adé were inside the information centre at Sonsbeek Park in Arnhem, following the live Dutch national news broadcast, and Cornelis had his camera trained on a television set on which the programme was being broadcast.4

As was the case in the Buren film, discord is immediately apparent in the introduction to the Sonsbeek film. In the former, there was reference to the conflict at the Guggenheim. In the Sonsbeek news broadcast, we hear someone speaking on a telephone, saying: ‘Yes, okay, we have, I think, I believe, not so much a more or less aesthetic standpoint like the one shown in Arnhem, in Sonsbeek Park … We attach, I believe, more importance to the social aspect that is associated with it, in order to speak to people in a different way.’ This critical voice – of someone wanting to pick apart the autonomy of the art, minimal art for example, that dominated Sonsbeek in 1971 – is the first but by no means the only one in the film. At the time the exhibition opened, the Netherlands, and Arnhem in particular, were in the midst of a vehement controversy, which pitted most notably the BBK national artists’ association against the organisers of Sonsbeek. With their slogan ‘A Million Guilders of Elite Art for the Elite’, BBK artists argued that ‘Sonsbeek is a perfectly proper, neat exhibition. Sonsbeek is much ado about nothing. Sonsbeek is a fact packed in a plastic bag and put in a display case, whereupon everybody declares in the newspapers that it smells delicious. Conviviality, magic, chaos, fantasy and people – all of that is missing. Sonsbeek is dried out and dead.’

Cornelis’s film gives ample attention to the BBK, stretching the conflict right across his documentary on the event. We see BBK slogans and posters and hear opinions from BBK artists no fewer than four times. It is also remarkable that in this film, Adé presents the disgruntled artists with a wide-open target. He does not even ask a question but states: ‘This catalogue for Sonsbeek is a dirty piece of propaganda.’ A BBK artist duly responds: ‘Yes, that’s what we think, at least. There are of course others who are of the opinion that this is information. Then we immediately ask ourselves, information for whom? We feel it is information for a very small in-crowd, a very small elite.’ Cornelis and Adé bring the protesting artists in front of the camera three more times. The second time, his insinuation equally evident, Adé asks: ‘The money spent on Sonsbeek buiten de perken was badly spent. Why?’ He proceeds to ask: ‘Does that mean that the art is reserved for a very small group of people with highly cultured backgrounds?’

In any conflict there have to be at least two parties, which, in our case, begs the question of who is being presented as the opponents of the protesting artists. Here the opponents can only be the organisers of the exhibition, including Wim Beeren, the spokesperson for the working committee responsible for selecting the artists and the organisation of Sonsbeek buiten de perken, and Cor Blok, the exhibition’s educational advisor. Both men make lengthy appearances in Cornelis’ film. One of Blok’s answers makes clear that Adé has put him firmly on the defensive: ‘There are so many things that are more important. Should you spend so much money to organise an exhibition of visual art? In fact, you should begin by changing all of education, because that is where the problems come from. That’s why people go into the world so badly prepared, among other things, in this field.’

Other ‘opponents’ appear before Cornelis’s camera, including local Arnhem politicians who facilitated the exhibition. Interviewing two of Arnhem City Councillors, Adé solicits their reaction to the local artists’ slogan ‘Elite Art for an Elite Group.’ Both councillors react negatively, one of them answering angrily:

If the population were to decide – and sometimes people say that participation should be taken to extremes – … whether there should be any support at all given to visual artists, then they would have to fear that the main lines of the population would alas all send them to a concentration camp, and that is the issue that they do not always take into consideration.

In the film, even artists participating in Sonsbeek buiten de perken, such as Ronald Bladen and Robert Morris, have to answer questions about the elitist aspect of the exhibition, the bone of contention for the BBK artists. The artists rebut the claims of elitism. Morris, for example, says about his observatory, which was in fact not yet complete when the exhibition opened: ‘I hope that when it is finished, it will be a space that makes this area very special, that people without any knowledge that it is in fact partly an observatory will be able to enjoy it, because I don’t think that this is fundamental to it. It is a space, a place to be, for anyone.’ Cornelis and Adé also seek the opinion of an art critic, Lambert Tegenbosch, who does not spare the exhibition. Without referring to the criticism from the BBK, he says, ‘When I criticise the expense, it is for artistic reasons. They are critical objections. I mean, the art that we are seeing here is art that has been established for who knows how many years. It is recognised art. A magazine has been devoted to it – it is all established art. We no longer have to be shown what it is about.’

Fig.4

Jef Cornelis

Still from Sonsbeek buiten de perken 1971

© Courtesy Argos, Brussels

The artists protesting against Sonsbeek are allowed to speak out in Cornelis’s film, as are their counterparts – the Arnhem politicians, the Sonsbeek organisers and the participating artists – who are confronted with the protest actions unfolding in front of the Flemish public broadcasting camera, in the hands of Cornelis, and of the microphone of the then Belgian Radio and Television, in the hands of Adé, reporting on the conflict. But Adé and Cornelis did more than mediate between existing or available critical voices. They also single-handedly produced a critique of their own. This is especially evident at the very end of the Sonsbeek film, when Buren appears before the camera and microphone (fig.4). Adé and Buren are standing in front of a sculpture by the Dutch artist Wim T. Schippers, and Adé asks Buren, who was in the show, to ‘take a critical look at what happened in Sonsbeek.’ Buren eagerly accepts Adé’s invitation and offers a cutting response, first by declaring that Sonsbeek is a museum exhibition, and that ‘you don’t step outside the boundaries of art culture simply because you’re exhibiting in the street, in a field, etc.’ Perhaps the organisers of Sonsbeek 71 would not have entirely disagreed with that, but Buren then adds that art in the streets, in other words, art ‘outside the boundaries’ of the museum – which was the ambition of Sonsbeek 71 – disturbs people who had not asked for it. The people, Buren argued, have nothing to do with this art, are unnecessarily burdened by it, and thus no one should be surprised that they are reluctant to respond to it. Here Buren is arguing on behalf of the museum context, where art only ‘pesters’ people when those people have themselves chosen to enter the museum.

In Cornelis’s film, the whole concept of Sonsbeek buiten de perken – to take art beyond the confines of Sonsbeek Park and explore spatial relationships and new communication technologies – is skilfully criticised, with Buren appearing to have the last word against the exhibition’s aims: on the one hand, by claiming that one cannot simply go outside the boundaries of the museum; on the other, that the organisers are behaving like enemies to the people when they do move beyond the museums.

Yet is this really the last word? In fact, Cornelis kept it for himself, as he sat down with his editor to edit the film. With Adé, the cameraman and the sound technician absent, Cornelis was free to insert certain images – images mentioned earlier in this text – at the point when Buren is speaking out against art outside the boundaries of the museum, in the public realm. Instead of shots of Buren’s work exhibited at Sonsbeek, Cornelis chose images he had filmed for the Zoeklicht programme, namely the detailed shots of Buren’s work at the Wide White Space Gallery in which the pavement in front of the gallery is prominent, and in which we see the passers-by who so captivated the camera but who showed no interest whatsoever in the art that was out there, in the street. In the Zoeklicht film, the woman and her poodle appear just as Adé asks Buren about his work being for sale. In the Sonsbeek documentary, Cornelis illustrates the arguments of Sonsbeek’s most intelligent critic with that critic’s own work: while Buren is busy claiming that ‘you don’t step outside the boundaries of art culture simply because you’re exhibiting in the street, in a field, etc,’ Cornelis shows Buren’s work out there on the street, in de Schildersstraat in Antwerp, for people ‘who happen to be and who will be pestered by things they couldn’t care less about’, as Buren says. What Cornelis is showing in the Sonsbeek film is the very audience that had never asked to be confronted with art in the streets: the people walking past Buren’s Travail in situ in Antwerp.

Cornelis, moreover, does not show the entire work in Antwerp, only the portion that is outdoors, which the people are walking past. Had Cornelis instead shown the travelling shot, moving from inside the gallery towards the street, for example, he would have reinforced Buren’s argument that one cannot go beyond the boundaries of the cultural or the artistic. Cornelis would have demonstrated that the work seen outside the gallery had to do with the work presented indoors, and consequently that art was not separated from the art institution, in this case the gallery. But in showing the outside portion of the work, Cornelis’s message is clear: Buren says that art belongs in the museum and that you must not disturb unsuspecting residents with art, but Buren is himself doing just that. And is it true that these passers-by are being approached aggressively? In response, Cornelis lets us see numerous unsuspecting citizens filing past Buren’s work, apparently oblivious to the fact that Buren’s work is even there.

Fig.5

Jef Cornelis

Still from Sonsbeek buiten de perken 1971

© Courtesy Argos, Brussels

It seems to me that there is more happening here than an ordinary documentary about an exhibition, more than television mediating a conflict. To argue this point, I want to take one more look not at the end of the film, but at the beginning. As I mentioned earlier, Cornelis was at Sonsbeek Park as a witness to the opening of the exhibition on live national television, his camera set up in front of a television set to record the live news broadcast. At the time, Cornelis may not have seen what was being aired immediately before the news item on Sonsbeek. Only later, when he was editing the film, would he have seen that the item that preceded the statement about Sonsbeek was a cartoon of two figures, one strangling the other (fig.5). What could an animated cartoon possibly have to do with Sonsbeek? Nothing, of course. The drawing has no relevance whatsoever to the exhibition, but it nonetheless turns out to be very pertinent to Cornelis’s film about Sonsbeek buiten de perken, for that cartoon stranglehold has everything to do with the way Cornelis approaches art, artists and art events.

The beginning of the Sonsbeek film is a motto. It is not about whether the local artists and politicians, the organisers, the participating artists or the proud art critic who enjoys nationwide respect are correct or not. Cornelis had no intention of promoting the opinions of any of the parties involved. Instead his Sonsbeek film is a series of negations. Very explicitly with words, but also very subtly with visual images, Cornelis lets points of view and visions clash against one another. The filmmaker is more interested in these clashes and oppositions than in presenting any standpoint that might be called his own. What is essential is the conflict itself – the difference in meaning, standpoint or vision, without the need for them to be interpreted as his own.

Yet a distinction should be made between the two ‘secretively’ critical moments in Cornelis’s films: on the one hand, the symbolic appearance of the lady with the poodle in the film on Buren’s work at the Wide White Space Gallery and the images of Buren’s installation at that same gallery in the Sonsbeek film; on the other, the initial cartoon scene in the latter film. These fleeting first images – the strangling cartoon figures – go virtually unnoticed, unless one looks at the film frame by frame. Viewers would probably not even have caught those first frames in the Sonsbeek film, but they may have had the feeling that there was something wrong with the way it begins. In this sense, the opening of the film is a kind of index or subscript. The strangling cartoon figures are a clue, pointing to something being ‘wrong’, something not quite right. This is to argue that in Cornelis’s practice, television is more than an instrument to promote any individual opinion or an instrument to arbitrate conflicts. Television itself is fundamentally discordant.

English translation of the conversation between Georges Adé and Daniel Buren in Jef Cornelis’s short untitled film made for Zoeklicht op de culturele actualiteit, Belgian Radio and Television, 1971

Georges Adé

You always repeat the same thing.

Daniel Buren

Formally, it’s the same thing, in the sense that it’s always vertical white and colour stripes. It’s not always the same colour – in fact, it’s never the same colour.

Georges Adé

But the colours don’t mean anything.

Daniel Buren

No, the colours don’t mean anything. They’re never mixed. There’s never a red, a green, and a yellow. But it can be any colour. One at a time.

Georges Adé

One opposition at a time?

Daniel Buren

A white and a colour, that’s all. But in fact it’s never exactly the same thing. The materials are the same. What we see gives the impression of being identical.

Georges Adé

Yes?

Daniel Buren

Here, for example, the experience of doing an exhibition in the same gallery as two and a half years ago, using exactly the same situation as before, the only difference being that the colour’s not the same – which I think will hardly be noticed – is a way of showing that the exact same thing is completely different. Firstly because there’s a difference of two and a half years between the two and secondly because the whole story around it is different, which I think changes things enormously.

Georges Adé

We see this in a completely different way from two years ago.

Daniel Buren

Yes, I think that plays a role: that’s the relationship inside the same work. But it also plays a critical role in relation to art, as we know it in galleries in general.

Georges Adé

That’s what I’d like you to explain to me. I think you use the term rupture in your writings. In what way does this represent a rupture?

Daniel Buren

I don’t say that what I do, what I’ve made visible until now, is a rupture. I’m trying to see if it is. At any rate, if it were, it wouldn’t take the form of an image of rupture: that would be stupid. When I say that it’s critical, it’s because it clearly plays in relation to, meaning that it addresses a number of problems – from very simple problems like the development or so-called progress of artists and art.

Georges Adé

You believe in that?

Daniel Buren

No, exactly, I don’t. So, from simple problems to problems much more specific to the proposition itself, like the repetition, the use of supports, a surface covered by this work on given supports, be they inside or outside, in the gallery or in the street.

Georges Adé

Precisely. I’m going to say something commonplace, no doubt, and maybe naive. You’ll tell me to what extent it is naive or valid. You exhibit in a gallery, don’t you?

Daniel Buren

Yes, of course.

Georges Adé

And everything you do is a work of art, isn’t it?

Daniel Buren

The issue that I’m trying to tackle is that everything you put in a gallery, without value criteria – which come afterwards – is an art work. And it’s an art work partly and especially because what’s found in a gallery generally has no interest or is no longer possible outside of the gallery. Or outside it’s done differently, it’s done for the outside context, which amounts to roughly the same thing. Sculpture has always been done outside and in relation to the outside. The problem that I’m raising with this work is that what you see in the gallery in any case … even when we are no longer in a gallery as such … it is still a cultural venue, a structure one can conceive on.

Georges Adé

But the stripe continues inside. It follows a path.

Daniel Buren

It continues inside because, since I’m using the gallery, it’s a painting that is seen twice, which raises the specific problem of paintings, which are generally seen once.

Georges Adé

By the way, do you sell this thing?

Daniel Buren

Sell? Well, if someone wants to buy it, I don’t keep it for myself. But selling is saying a lot because there aren’t a great many people interested in buying something like this. And when they’re interested, you wonder why they’d want to have something that they can make themselves. But it’s not outside the economic system. That would be unrealistic.

English translation of the conversation between Georges Adé and Daniel Buren in Jef Cornelis’s television documentary on the exhibition Sonsbeek buiten de perken 1971

Georges Adé

Let’s take a critical look at what happened in Sonsbeek.

Daniel Buren

In what sense?

Georges Adé

In yours.

Daniel Buren

All I can say is that the work I wanted to do was simply the same work I usually do exclusively in the museum setting, even though in this case the whole exhibition, I think, was in the street, in the country, outside. It’s not a huge critique, just a way of making a point: you don’t step outside the boundaries of art culture simply because you’re exhibiting in the street, in a field, etc. It’s a way of continuing the kind of work I do personally and, in this particular context perhaps, of relating it critically to this supposedly new form of art, etc.

Georges Adé

So you think that when you exhibit in a park or smack in the middle of nature, you’re not leaving the confines of a museum or a gallery?

Daniel Buren

No, you’re not at all. Especially not in the case of this exhibition. It’s clearly a museum exhibition in every respect; only the form has been changed somewhat. Instead of having all the works on display inside the walls of the museum, the museum has exploded a little and exhibits in different places. The very basis of organisation of an exhibition like this is completely museological. The advantage of the art found in museums, even the most awful art, is that it only disturbs people who set foot in the museum. When art, as is, is taken out of the museum’s usual boundaries, without being questioned, its impact on an uninformed audience is much more aggressive. Which makes their reluctance understandable. It’s a way of more or less assaulting not only the middle classes who have a certain desire to go to museums but also people who happen to be in the street and who will be pestered by things they couldn’t care less about.