Cultural amnesia – imposed less by memory loss than by deliberate political strategy – has drawn a curtain over much important curatorial work done in the past four decades. As this amnesia has been particularly prevalent in the fields of feminism and oppositional art, it is heartening to see young scholars addressing the history of exhibitions and hopefully resurrecting some of its more marginalised events.

I have never become a proper curator. Most of the fifty or so shows I have curated since 1966 have been small, not terribly ‘professional’, and often held in unconventional venues, ranging from store windows, the streets, union halls, demonstrations, an old jail, libraries, community centres, and schools … plus a few in museums. I have no curating methodology nor any training in museology, except for working at the Library of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for a couple of years when I was just out of college. But that experience – the only real job I have ever had – probably prepared me well for the archival, informational aspect of conceptual art.

I shall concentrate here on the first few exhibitions I organised in the 1960s and early 1970s, especially those with numbers as their titles. To begin with, my modus operandi contradicted, or simply ignored, the connoisseurship that is conventionally understood to be at the heart of curating. I have always preferred the inclusive to the exclusive, and both conceptual art and feminism satisfied an ongoing desire for the open-ended. ‘Illogical judgments lead to new experience’, wrote Sol LeWitt in 1969.1 Rejecting connoisseurship was part of a generational rebellion against the Greenbergian aesthetic dictatorship that was becoming obsolete inNew York by the mid 1960s. Like the pop and minimal artists from whom I learned about art, I adamantly turned my back on the diluted excesses of the second generation of Abstract Expressionists.

In the 1960s critics rarely curated, and artists never did, but all kinds of boundaries were beginning to be blurred, as in the fusion or confusion of painting and sculpture that marked the beginning of minimalism. I called it the ‘Third Stream’ (as in jazz) or ‘Rejective Art,’ and then ‘Primary Structures’. My first exhibition was Eccentric Abstraction, held in 1966 at Marilyn Fischbach’s gallery in New York. It, too, was an attempt to blur boundaries – in this case between minimalism and something more sensuous and sensual – that is, in retrospect, something more feminist. There was nothing innovative about the exhibition except the art. Gallery director and good friend Donald Droll was there to help me, and there were only eight artists to deal with: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams, Bruce Nauman, Keith Sonnier, Gary Kuehn, Don Potts and Frank Lincoln Viner. Afte Eccentric Abstraction, I organised a couple of shows for the Museum of Modern Art travelling exhibitions department, which I barely count since I did not have the opportunity to install them myself. Installation is when you finally get to see what you have as a whole, instead of in fragments. Like holding a finished book in your hands at last, it makes the entire gruelling process worthwhile. I suspect every curator feels the same.

In November 1968, when Paula Cooper opened her first gallery on Prince Street in New York, I devised a show of major minimal works, with artist Robert Huot and Socialist Workers Party organiser Ron Wolin, for the benefit of Student Mobilization against the war in Vietnam. I had just returned from a radicalising trip to Argentina (with French critic Jean Clay) during the military dictatorship. There we had met members of the Rosario group in the midst of their Tucamán Arde campaign (which in the last decade or so has finally been recognised as the groundbreaking work that it was). This was the first time I had heard artists say that they were not going to make art until the world was changed for the better. It made a profound impression on me.

In Latin America I was also trying to promote a series of ‘suitcase shows’ that could be transported from country to country by artists, bypassing the institutions and allowing more international networking and face-to-face interaction between artists. When I got back to New York I met Seth Siegelaub, who had similar ideas and was beginning to implement them. Soon afterwards, the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC) was founded around the issue of artists’ rights and was soon concentrating on anti-Vietnam war actions. Both Siegelaub and I and his ‘gang of four’ – Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, and Lawrence Wiener – joined AWC, as did Carl Andre and, peripherally, my dear friend and modest mentor Sol LeWitt.

There was a sort of unconscious international energy: ideas in the air formed, like Alzheimer’s disease, of an incomprehensible tangle of nerves and interactions between artists of very different stripes. It emerged from the raw materials of friendship, art history, books, and a fervour to change the world and the ways artists existed in it. The cross-disciplinary Do It Yourself or DIY movement that is being rediscovered today in very different contexts by a much younger global generation was an integral element of this international network. You did not apply for grants: you just did what you could with what was at hand. For me the point of conceptual art was precisely the notion of doing it ourselves – bypassing mainstream institutions and the oppressive notion of climbing the art-world ladder by having an idea and directly, independently, acting upon it.

While conceptual art clearly emerged from minimalism, its basic principles were very different, stressing the ‘acceptive’ and open-ended in contrast to minimalism’s ‘rejective’ self-containment. For a brief period, Process art (Arte Povera inEurope) also intervened, with its perverse denial of materiality in favour of an obsession with materials. Scattering, spattering, puddling and pulverising, it opened up new ways for the artist to identify actively with what he or she was making, including performance, street works, video, and other ephemeral rebellions against what was then called the ‘precious object syndrome’.

I liked the idea of fragmenting my job, too. I have never considered criticism as an art in itself, separate from its subjects, as some would have it, but as a text woven like textile (the etymological root is the same) into the art and the systems that surround it, including exhibitions. In the 1960s, I was trying – rather unsuccessfully – to execute a kind of chameleon (or parasitic) approach to writing about art, choosing a style of writing that was congruous with the artist’s style of art making (easier said than done.) Dada was my art-historical field, if I could be said to have had one, and Ad Reinhardt was a hero and a major influence because of his fundamental iconoclasm. In different ways, both Dada and Reinhardt were attempting a tabula rasa, a clean slate on which to draw plans for a new world and a new kind of art. Just as minimalism and then conceptual art offered apparently clean slates to artists, so they did to curators. (Of course, the palimpsest on those slates became obvious in retrospect; history always catches up with rebels.)

It seemed perfectly logical that if the art was going to change so drastically from its immediate predecessors, then criticism and exhibition strategies should change as well. Artists were making blank films; they locked galleries, and practised doing nothing. They were denying conventional art by emphasising emptiness, cancellation, the vacuum, the void, the dematerialised, the invisible. Value judgments were beside the point – another reaction against the narrow definition of quality disseminated by the Greenbergians, as well as a way of defying and questioning authority in the ‘wider world’. The exhibitions I curated by numbers certainly illustrated this all-inclusive aspect. As Hanne Darboven wrote in 1968: ‘Contemplation had to be interrupted by action as a means of accepting anything among everything.’2 Huebler said that there were already too many objects in the world and he did not want to add any more. Instead, he wanted to make an art that embraced everything about everything. The more expansive, the more inclusive an exhibition could be, the more it seemed coherent with all the other so-called revolutions taking place at the time. I began to see curating as simply a physical extension of criticism.

In May 1969 I organised the first of the numbered shows – Number 7 at Paula Cooper’s gallery. I cannot remember where the number came from, but it had a factual base of some kind. This was the progenitor of the other numbered shows, and it doubled as a rather un-lucrative benefit for the AWC. There was only one card, with the artists’ names: I called myself the ‘compiler’ of the exhibition rather than its curator. Cooper’s gallery had three relatively small rooms, and there were thirty-nine artists, all or most of whom were also in the later number shows. The largest room looked virtually empty, although it contained nine works including one of LeWitt’s first public wall drawings, Hans Haacke’s Air Currents (an unobtrusive fan in the corner), Existing Shadows by Bob Huot, a blip by Richard Artschwager, a Lawrence Weiner pockmark on a wall from an air-rifle shot, a magnetic field by Robert Barry, a secret by Steve Kaltenbach, Ian Wilson’s Oral Communication (the last three were invisible), and a tiny found wire piece by Andre on the floor. The middle room featured two empty walls painted blue (by Huot), while the smallest room was filled with conceptual pieces, mostly books, photos, photocopies and texts on one long table. I think this show was far more visually interesting in terms of installation than the later numbered ones. But since no documentation of this exhibition remains, this may be just wishful thinking.

I am ashamed to say that there were only four and a half women in Number 7: Christine Kozlov, Rosemarie Castoro, Hanne Darboven, Adrian Piper, and Ingrid Baxter (who was half of the NE Thing Co.). 557,087 was not much better, despite the fact that it was almost twice the size. In terms of global representation, 557,087 was even worse. I can only mutter in my defence that I had not yet seen the light. I became a feminist a year later.

When I took on 557,087 at the vast Seattle World’s Fair Pavilion in 1969 and its sibling, 955,000 in Vancouver in 1970, I was hardly prepared to execute something on this scale. Both shows consisted of sprawling assortments of objects, non-objects and site-specific works. My lack of training and lack of respect for the ubiquitous white gloves must have shocked the professionals at the time. But on another level, ignorance was an advantage: I had as little baggage as the artists. The numbered exhibitions of 1969–73 were as scattered and expansive (you might say unfocused) as the art itself. Although 557,087 was sponsored by the Contemporary Art Council of the Seattle Art Museum, it did not take place in the museum proper, but at the former World’s Fair Pavilion, whose marginal position was of course highly appropriate.

I took seriously Barry’s 1968 statement: ‘For years people have been concerned with what goes on inside the frame. Maybe there’s something going on outside the frame.’3 Taking the museum as the frame, 557,087 and the subsequent Vancouver version, 955,000, were the first shows I did – and maybe the first shows anywhere – that took place half outdoors, around the city in a radius of fifty miles. Though maps were provided at the museums, I think it is safe to assume that very few people ever saw the whole exhibition – a fragmentation, again, appropriate to the art itself, like Artschwager’s blips or John Baldessari’s labels marking the boundaries of the ghetto. While public art is not seen with the private intensity that art in museums generally receives, it is seen by people who would not be caught dead in a museum. Working outside of the museum or the gallery is my favourite part of curating, and the riskiest, since it exposes both artists and audiences to unexpected and unfamiliar experiences, which can lead to vilification and vandalism.

The Seattle and Vancouver exhibitions were the first of the numbered shows to have a catalogue – 10 x 15 cm loose index cards to be arranged and read randomly, including my introductory, or interfoliated, text. (Forty-two cards and three artists were added when the show moved to the Art Gallery of Vancouver and the Student Union at the University of British Columbia, where the title became 955,000.) I liked the idea that the reader could throw out the cards she or he did not like, which paralleled the ‘anti-taste’ bias of the entire exhibition. The show was so large that the public would be overwhelmed and have to depend on its own perceptions. The index card form was carried over to the subsequent numbered exhibitions: 2, 972, 453 at the Centro de Arte y Communicación in Buenos Aires in 1971 (this included only artists that were not in the first two shows, among them Siah Armajani, Stanley Brouwn, Gilbert & George, and Victor Burgin) and c. 7,500 at CalArts in Valencia, California, in 1973–4. I did not install either of these exhibitions and c. 7,500 travelled to several other venues.

The titles of these numbered exhibitions were approximate population figures for the cities where the shows were held. I was of course looking for something neutral — non-associative, non-relational, according to the gospel of the era. I was also determined not to provide a new category in which disparate artists could be amalgamated. Numbers were, as we know, an important factor in conceptual art. There was a certain unspoken competition to see how far an artist could really go: On Kawara had One Million Years books, Barry produced One Billion Dots (recently reconstituted in colour) and Dan Graham’s March 31, 1966 covered an infinite span from the edge of the universe to the microspace between the eye’s cornea and retina. No discipline was safe as artists looked far afield for raw material. I have in mind the arguments Robert Smithson and I had on finity versus infinity (as though you could argue about such a thing): he was for finity; I was, idealistically, for infinity.

Although the theoretical branch of conceptual art, represented by the likes of Kosuth, Mel Bochner, and early Art & Language, was fond of philosophical analysis and boundaries, the free-form branch with which I identified was essentially utopian in its openness to everything extant. In this branch we were obsessed with time and space, body and mapping, perception, measurements, definitions, the literal and the quotidian, and with enigmatic, tedious activities that appeared simply to fill space and time, the kind of unexceptional lived experience that might not be available to those not living it. One of my many focuses – as I wrote in the card catalogue for 557,087, a remark which resurfaced years later in my book Overlay and which resonated with my ongoing fascination with archaeology – was in ‘deliberately low-keyed art [that] often resembles ruins, like Neolithic rather than classical monuments, amalgams of past and future, remains of something “more”, vestiges of some unknown venture.’ I went on to talk about ‘the ghost of content’ hovering over the most obdurately impenetrable art and suggested that ‘the more open, or ambiguous the experience offered, the more the viewer is forced to depend upon his/her own perceptions.’

Peter Plagens, reviewing 557,087 in Artforum, accused me of being an artist. He wrote: ‘There is a total style to the show, a style so pervasive as to suggest that Lucy Lippard is in fact the artist and her medium is other artists.’4 I was annoyed by this at the time, but in another sense it is not such a bad assessment of all curating, as it pinpoints one of the prime issues of the period in which these shows were made – the deliberate blurring of roles, as well as boundaries between mediums and functions. Over the years I admit I did my best to exacerbate this confusion, collaborating with several conceptual artists, LeWitt, Barry, Huebler, David Lamelas, among others. In a labyrinthine text in which I fused my contributions to a book and exhibition project by Lamelas and a collaboration with Huebler, I wrote: ‘It’s all just a matter of what to call it. Does that matter? … Is a curator an artist because he uses a group of paintings and sculptures in a theme show to prove a point of his own? Is Seth Siegelaub an artist when he formulates a new framework within which artists can show their work without reference to theme, gallery, institution, even place or time? Is he an author because his framework is books? Am I an artist when I ask artists to work within or respond to a given situation?’5

The ‘given situation’ was a reference to my chain reaction ‘exhibition’ that took place in a 1970 issue of Studio International guest-edited by Siegelaub, which was inspired by LeWitt’s line: ‘The words of one artist to another may induce an idea chain.’6 Around the same time I also did a show called Groups at the School of Visual Arts, in which I asked artists to photograph groups of people. I had an ulterior motive here, as I was writing a novel – I See/You Mean – that started out solely as written descriptions of group photos and an index; it eventually opened up into something else, but conceptual art was its prime influence.7

I went on to ask, ‘Is Bob Barry an artist when he “presents” the work of Ian Wilson within a work of his own, the process of the presentation being his work and Ian’s remaining Ian’s? If the critic is a vehicle for the art, does an artist who makes himself a vehicle for the art of another artist become a critic?’8 This game of inclusions could go on and on, in a manner reminiscent of Dada’s meaningful play. ‘Imagine’, John Lennon had exhorted us, and the power of imagination was at the root of even the stodgiest attempts to escape from the ivory towers in which art seemed imprisoned.

In another version of role-blurring, I was asked to write a critical text in absentia (as I was living in Spain) for the influential Information show at MoMA in the momentous year of 1970, the year of Cambodia Spring and of the Kent State and Jackson State massacres. When I produced an incomprehensible randomly selected ‘thing’, curator Kynaston McShine had no choice but to list me as an artist, since the critical text he had asked for was definitely in absentia. (He let me do another random ‘readymade’ text for a catalogue of a Duchamp exhibition at MoMA. We got away with a lot in those days!)

I did not become an artist by collaborating with artists, but their fixation on the ‘ordinary’ was what permitted my participation in their work. The introduction of text as art and the notion of the artist working in a study instead of a studio – as John Chandler and I put it in our 1967 article ‘The Dematerialization of Art’– gave me, as a writer, an entrance into the game.9 The artists themselves were trying to change the whole definition of artist, and I was a willing accomplice, in part because I never wanted to be a critic, and because the word sounded antagonistic to the artists with whom I associated. Since they certainly were not conforming to what was expected of visual art, I saw no reason why I had to meet the expectations of criticism.

In Seattle and Vancouver, however, I was not given the opportunity to play at being an artist: I was forced to actually make a number of the pieces in the shows because there was no money for artists’ airfares. Curation became unintentionally creation. Moreover, the catalogue cards describing the artists’ projects often bore little resemblance to anything that was actually in the show. This was usually for one of two reasons: the artist changed her or his mind, or the piece was so out of scale or proportion to the time and money available. I am not even sure every artist listed actually produced anything. We tried to construct each work according to the artist’s instructions. Sometimes we succeeded. For instance, Smithson was not in Seattle and so he gave me instructions to take ‘400 square snapshots of Seattle horizons – should be empty, plain, vacant, surd, common, ordinary, blank, dull, level.’ I vividly remember going out one afternoon to find places around hilly Seattle that met his criteria. Andre was not so lucky. His instructions were simply: ‘Timber Piece, 28 units c. 1′ x 1′ x 3″ and a little drawing. I pictured ‘timber’ as raw logs, where he meant finished lumber. It looked great, but he always insisted that it was my piece, not his. Barry Flanagan’s and Robert Roehm’s rope pieces did not come out quite right either. Randy Sims’s white arc, spray-painted on trees, looked lovely in his mock-up and awful in the flesh. The LeWitt did not get executed in Seattle because of bad carpentry, nor did the Jan Dibbets, because of weather conditions. Richard Serra did not produce his own contribution to the Seattle show, but there is a plywood piece of his in the photographic record, and so someone must have made it. In Vancouver, the LeWitt was expertly executed by artist Glenn Lewis. Smithson managed to travel there somehow and made a major piece – Glue Pour.

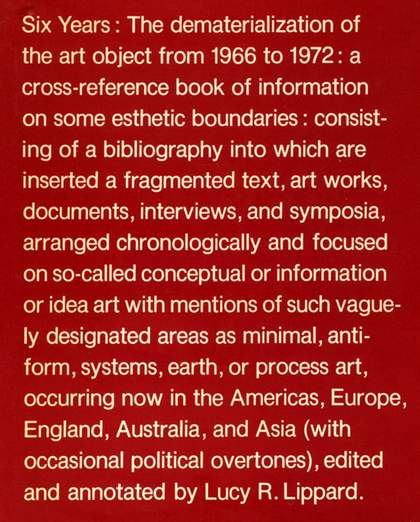

These two shows taught me more about the nature of the art involved than all the words that had gone under the bridge. They also made it abundantly clear – as did other contemporary exhibitions, such as When Attitudes Become Form, Op Losse Schroeven, and Information – that this work was fundamentally uncategorisable. For all the attention that my number shows are attracting today, they were not nearly as innovative as Siegelaub’s dematerialised exhibitions around the same time – especially his March show, which broke all exhibition conventions by taking place around the world at the same time, and The Xerox Book, which introduced the notion that an exhibition of real art rather than reproduced art could be presented in books, which in turn triggered the significant, if always marginal, cottage industry of artists’ books. Certainly, my compendium Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object etc. (the title was eighty-seven words long and covered the entire front cover of the book), could be seen as an exhibition (fig.1). It has also been called a ‘conceptual art object in itself’ and a ‘period-specific auto-critique of art criticism as act’. Ultimately, Six Years was probably my most successful curatorial effort, precisely because I am a writer and not an artist.

Fig.1

Front cover of Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972

Berkeley and Los Angeles 1973

The strategy in both the number shows and the book was one of over-the-top accumulation, the result of a politically intentional anti-exclusive aesthetic that was also a core value of feminist art, which hit me and New York in the fall of 1970 and which carried over into political activism. Since 1969, the Guerrilla Art Action Group had used text and performance to protest the hierarchy of museums and metaphorically to overthrow the US government. In 1970 Ad Hoc Women Artists Committee used conceptual art forms in feminist protests against the predominantly male Whitney Annual exhibitions. We distributed a fake press release purportedly coming from the Whitney, proudly announcing that since the museum had been founded by a woman it was only appropriate that that year’s sculpture show would consist of 50% women and 50% ‘non white’ (as we quaintly put it) artists. On the model of Kosuth’s faked artist’s membership cards to MoMA in 1969, we also forged invitations to the Whitney opening so we could organise a sit-in inside the museum, and we projected slides of works by women artists on the outside of the museum – a nice twist on site-specificity. (Thanks to our efforts and of the Women’s Art Slide Registry, the Whitney included four times as many women as they had before.) Luckily all this was done more or less anonymously, since the FBI had been called in to catch the criminals (they did not catch any). As Lee Lozano put it, ‘Seek the extremes. That’s where all the action is.’10

The last number show with cards as the catalogue – c. 7,500 in 1973 – was ‘an exasperated reply,’ as I wrote in the catalogue, ‘to those who say “there are no women making conceptual art”.’ The show ended in London, after travelling to seven venues, and so the population title became irrelevant. I had not thought of that. Among the twenty-six artists included in c. 7, 500 there were poets, writers, and performance artists as well as trained visual artists. The works were small and tight, with more informative cards (text on both sides) than in the previous card catalogues. Comparison of c. 7, 500 with the previous mostly male shows of conceptual art highlights the contributions of women’s art to the movement, primarily through an emphasis on the body, biography, transformation, as well as gendered perception.

There was a political bottom line to this work that incorporated a rather rarefied populism, the hope that by dematerialising the art object we could make it accessible to a far broader audience. But, in so doing, we forgot that the audience has to want it after it is made available. Blake Stimson has suggested that conceptual art had ‘little of the social utopianism that drove’ earlier avant-garde movements, but I would argue that this idealistic embrace of everything about everything was indeed utopian, a term I do not reject: why not go for the ideal?11 However, this embrace was limited to the art world, which is where we lived, for better or worse. At the same time it made sense for us to be primarily concerned with art institutions, the distribution systems, etc, precisely because that is where we lived, what affected us most, where we had the knowledge and some power (if not much) – in other words, where we could effect change. The idea was that the revolution would happen because of radical change in every sector. The sum of the parts would add up to permanent political change. Thus, if everything could be art and everything was worthy of being the subject of art, then it seemed – in 1969 – that curating itself might soon become obsolete. The fact that it has not signals an ultimate failure. Despite its huge influence within the art world up to the present, conceptual curating remains what Luis Camnitzer has called ‘full-belly art’.12

When one thinks about it, sedentary exhibitions are odd vehicles for communicating and informing about global issues, but they can allow curators and artists groups to make what I have called exhibitions-as-art – collages, or collective art works in the exhibition format. As an example I could refer to the double windows at Printed Matter facing onto Lispenard Streetin New York, which I curated as an ongoing exhibition for several years. Group Material, Anti-World War 3, CoLab and PAD/D (Political Art Documentation/Distribution) were among those who pioneered this conceptual work in New Yorkaround 1980. Jerry Kearns and I organised a number of similar shows together, and later I worked with groups in Coloradoto produce shows in which the issues – homophobia, the Central American wars, consciousness of place – took precedence over individual artists’ production. We do not see much of this type of show these days, as society is increasingly ‘based on an accumulated individuality instead of a community structure’, as Camnitzer has put it. The last exhibition I curated – Weather Report: Art and Climate Change, in 2007 at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art – was conventionally installed inside the gallery, but it also included seventeen public pieces around town, ranging from sculptures to photography displays, to performances, children’s drawings in the public library, and a newspaper insert. Many of these works were specific to places where global warming would drastically affect the environment.

In my favourite review of the second edition of& Six Years, artist Liam Gillick chastised me for understating in retrospect the power of the ideas that emerged from 1966 to 1972. He argued that the artists, critics and organisers at the time ‘articulated a set of thinking and a number of social shifts that were not limited to art and thereby opened up the territory available to us all’.13 He is right, because the imaginative richness and freedom of the era are with me still.