Between 1978 and 1983 I worked for the German art magazine Kunstforum International that planned to publish its fiftieth volume in 1982, the year of the seventh dOCUMENTA. I proposed that we should dedicate the issue to the history of the documenta, combining our minor jubilee with the major event that had re-established West Germany as an international forum of modern art in 1955.

Having heard that a dOCUMENTA archive existed in Kassel, I expected that little work would be needed. ‘Just grab the photos and run’, I thought, but I was wrong. The archive in Kassel turned out to be quite a respectable library, consisting of catalogues and books on modern and contemporary art, most of them debris from the previous six exhibitions sent in by gallerists and artists, or bought for, and left behind by, the various exhibition committees. More appropriate to the name and function of an archive was an impressive collection of press clippings and reviews, stored in folders that also contained letters, drafts and other material written by the founders and curators of the first six dOCUMENTAs. When I asked for installation photographs of the exhibitions, however, I was shown a metal locker in the corner of the room, brim-full of envelopes and files containing heaps of photographs and papers. But it seemed that the locker had been opened for me for the first time in years: a quick examination showed that most of the photographs were unsorted and had no comments, or only laconic comments, on the back, some not even giving the number of the documenta in which they had been taken. Most of the photographs were great – but so was the work of sorting and titling them that lay ahead of me.

I am a little wary about describing this unforgettable day in autumn 1981 because the two art historians who then ran the archive then became friends during my time there. They had taken over the archive only a year before and had their own priorities in reorganising it. Moreover, interest in installation shots – primary sources for the history of exhibitions and nowadays commonplace in curatorial studies – was then only just beginning to develop. During the weeks to come, which included my Christmas holiday, I sorted the chaotic material into chronological order, identified dozens of people and, using the catalogues, many works of art, as well as various views of the Museum Fridericianum.

Mind the gap

I tell this story not to glamourise my personal history but to give a sense of this Stone Age in the historiography of exhibitions. At the time, I wondered if the magazine issue I planned could ever be produced at all. I was not aware that I had just discovered a law of historiography, namely, that nothing is more difficult to obtain than material on events that were sensations only a couple of years ago (at least, in the age before Google).

There was then a gap between the historical and the contemporary, of between approximately five and fifty years. In this gap much material and information was lost or very difficult to find before archives began to be interested or jubilees dawned. The period between the first and the sixth documenta that I had decided to work on lay precisely within this gap: only one book dedicated to the history of dOCUMENTAs existed, documenta-Dokumente 1955 bis 1968: Texte und Fotografien, a collection of press clippings and assorted photographs edited by Dieter Westecker in 1972, that covered the first four exhibitions.1

But seldom have I been as happy in my professional life as I was during the weeks when I sifted through the layers of photographs and letters, the stratifications of six dOCUMENTA exhibitions from 1955 to 1977, unused by a posterity that had not yet discovered the relevance of this material. And seldom have I learnt so much in such a short time, comparing the catalogue lists and illustrations with the installation photographs of the pieces that had been shown (in early documentas these could differ sometimes). For the first time in my life I read the names of artists such as Reg Butler, Kenneth Armitage and Lynn Chadwick, having been familiar only with Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore in the context of British postwar sculpture. For the first time, too, I looked up names like Afro Basaldella, Ernesto de Fiori and Massimo Campigli – big shots in their heyday, though their heyday proved much shorter than expected.

I was born in 1950 and the first dOCUMENTA I had visited had been the sixth in 1977 (though I never confessed this to Harald Szeemann, who would not have forgiven me, dividing the world, as he did, between those who had and those who had not visited his documenta 5). Sifting through the stranded goods of six exhibitions was art-historical time travel for me, full of news and surprises.

Vintage prints

One of the main reasons I enjoyed my work was the astonishingly good quality of most of the photographs, especially the early ones from the first to the fourth documentas which were taken mostly by Günther Becker. It turned out that Arnold Bode, the creator of dOCUMENTA, had had the foresight to commission Becker to take photographs of the first dOCUMENTAs. Being a specialist in trade fairs, Bode knew that events like these only survive adequately in photographs of the installations and not through catalogues. Thus, he employed a more than adequate photographer, someone who seemed to have been aware of the delicacy of the task. In documenting the early documenta exhibitions, Becker was sympathetic to Bode’s combinations of spaces and sites, single objects and constellations of works. His photographs constituted the best part of the volume Mythos documenta that finally did appear in 1982, as number 49 of Kunstforum International and not, as planned, as number 50.2

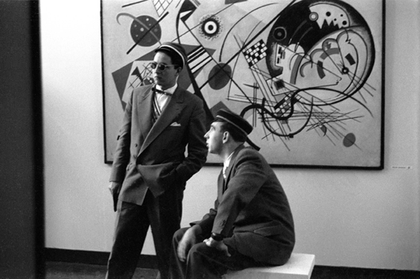

Of course there were exceptions to the rule, one being a very badly produced print that, moreover, had darkened with time and could not be reproduced in the magazine. It had been taken in 1959, judging by the Kandinsky it showed, but it had no identifying details on its reverse: no author, no date, no details, and – most unprofessional – no bank account. But I was fascinated by it: the unknown photographer, obviously an amateur, had seen the weird aspect of the scene, the contrast of the Kandinsky painting with members of a students’ fraternity, showing off their full regalia (fig.1). Thus, the image juxtaposed two very different German traditions: Kandinsky stood for the international free-trade zone of art that Germany had been between 1850 and 1914; the students stood for the nationalistic movements of the nineteenth century some of which eventually were entwined in many ways with the National Socialist nightmare of the twentieth. Whoever took this photograph was a fleeting witness to the contradictions of postwar (West) Germany. I was sorry not to know his name and not to be able to order a usable new print. Finally, I decided to include the visually unsatisfying print and dedicated a short essay to the unknown photographer and his little feat.

Fig.1

Hans Haacke

Fraternity students in documenta 2 1959

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2009

Photograph © Hans Haacke

By chance, I gave the very first Kunstforum copy of the dOCUMENTA volume, hot off the presses, in May 1982 to the artist Hans Haacke.

Preparing his contribution to the upcoming documenta that summer, Haacke visited me in my office in Cologne and a few days later he telephoned to tell me that he was the unknown photographer. As a twenty-three year-old student of art school in Kassel he had earned some money by working as an exhibition guard during the second documenta in 1959 and had taken some photographs. This print was not the only one that he had later given to the archive but obviously it was the only one to have survived there.3 Around thirty of them have been published since, after I convinced Haacke that they, alongside his student informel paintings of the time, were his very first major works of art.

A new topic

The weeks I spent researching the history of the documenta exhibitions were happy ones, because I had discovered a topic that was completely new to me and more or less to academic art history as well. Let us call it the pictorial history of exhibitions. It is always good luck in an academic career to discover a field of research where there very few competitors. But this career advantage was not the reason why the history of exhibitions became a Leitmotiv of my research, with a focus on Germany in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.4

In the beginning it was the fascination of time travelling, using the simple machines of photographs and slide projectors, that kept me devoted. Catalogues were poor records of exhibitions then because they were normally produced weeks before the opening; and contemporary critics generally described exhibitions from a subjective perspective, being more interested in judging in general than in reporting in detail. But how art was actually seen in its time cannot be judged by the comments of the self-chosen few, but only by how it was shown to the public. This insight may have become a commonplace now – among curators and in academic circles – but it was uncommon then or in any case underrated.

Anyone interested in this subject could turn only to a few books and essays, for instance, Lawrence Alloway’s The Venice Biennale: 1895–1968. From Salon to Goldfish Bowl, or Brian O’Doherty’s essay ‘Inside the White Cube’, published in Artforum in 1976, while the first general study on the subject, Georg Friedrich Koch’s 1967 book Die Kunstausstellung. Ihre Geschichte von den Anfängen bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts (The Art Exhibition. Its History from the Beginning to the End of the Eighteenth Century) ended, as the title indicates, in the eighteenth century.

Interest in the subject grew in the 1980s. Inspired by the success of installation art, dOCUMENTA 7 made a major contribution by publishing Germano Celant’s essay ‘A Visual Machine. Art Installation and its Modern Archetypes’ (Eine moderne Maschine. Kunstinstallation und ihre modernen Archetypen) in the catalogue. During the last few decades the history of exhibitions has become a prominent part of our business, although it is sometimes still amazing how little installation photographs of historically important exhibitions are taken care of.

Although dOCUMENTA was the first stop in my research in the history of modern exhibitions which focused on Germany in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, I have not become an expert in the special case of Kassel. Whenever I have a question, I simply telephone Harald Kimpel, who was a student working in the archive when I first visited it and later published his thesis on the history of the dOCUMENTA as well as several books which have become standard works. And, of course, the dOCUMENTA archive has become a professional institution, fully deserving its name, where you can find everything you need to know about the history of the dOCUMENTA, some of it maybe still with my handwriting on the back.

A summer’s day in Kassel 1955

After the Kunstforum volume on the history of the dOCUMENTA was published, I became obsessed for years by the idea of reconstructing documenta I, researching newspaper and magazine illustrations of the time which often gave important information in their captions. But for that task I was lacking a fundamental piece of information: a floor plan of the installations in the three storeys of the Museum Fridericianum. When I casually complained about this to Walther König, the famous Cologne art book dealer and publisher, he surprised me with a small and rare publication that in fact I had never heard of, containing a room-by-room floor plan of the first dOCUMENTA. The numbers of the rooms corresponded with installation shots, and this finally permitted a more or less complete reconstruction of the show.5

The booklet had been published in 1955 by a sponsor as an obviously unofficial but extremely helpful take-away. Walther König generously allowed me to photocopy it, and it became the basis for my slide show ‘A Guided Tour through documenta I’ that I have often given since then (a minor revolution in museum education, by the way, because it enabled you to visit a complete exhibition without leaving your chair). Enriched over the years with newly found photographs, this lecture was the basis of my essay on documenta I that appeared with only a few photographs in the book Die Kunst der Ausstellung. Eine Dokumentation dreißig exemplarischer Kunstausstellungen dieses Jahrhunderts (The Art of Exhibition. Documentation of Thirty Exemplary Art Exhibitions of This Century), edited in 1991 by Bernd Klüser and Katharina Hegewisch. In 1998 a French version was published, as I learned only recently.6

An insufficient answer

A couple of years later it dawned on me that the first dOCUMENTA of 1955 should be regarded as an answer to the Nazi exhibition Degenerate Art that took place in 1937, only eighteen years before. I wrote an essay about this relationship, the title of which expressed up my dissatisfaction with this answer: Entartete Kunst und documenta I. Verfemung und Entschärfung der Moderne (Degenerate Art and documenta I. Modernism Ostracised and Disarmed). This essay appeared in 1987 in the catalogue of the exhibition Museum der Gegenwart, curated by Jörn Merkert in the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, commemorating the gloomy jubilee of the Degenerate Art exhibition fifty years before, and in 1989 it became the central essay in my book Die unbewältigte Moderne. Kunst und Öffentlichkeit (the English version of the essay was published in Museum Culture. Histories Discourses Spectacles, edited by Daniel J. Sherman and Irit Rogoff in 1994.)7

The essay’s thesis was that only Harald Szeemann’s dOCUMENTA 5 was a complete and courageous answer to Degenerate Art, the first four documentas being simply too timid. It took thirty-five years before a documenta, the fifth, defied the seductive attacks and popular allegations of the Nazi exhibition with a controversial exhibition which was confident enough to concede that modern art had been a difficult subject from the beginning and still was, while the first dOCUMENTAs tried to win the public over with pedagogical pathos and questionable aesthetic allusions.

A German exhibition

The comparison with Degenerate Art emphasises how much documenta was a German exhibition before it became a truly international one. One might argue that it was a specifically West German exhibition, because official artists from East Germany were excluded from the start. But it was the exclusion of East German artists that made the first dOCUMENTA an allegory for Germany. Immediately after the war, art exhibitions had included both Germanys: in 1946 a large and important exhibition of contemporary art had been organised in the war-destroyed city of Dresden, combining artists from West and East Germany. It was curated by Will Grohmann, who also organised the exhibition East German Artists in the museum of the Bavarian, and hence West German, city of Augsburg in 1947. The immediate postwar German art scene had been one of a broad possible artistic community, all the more so as both postwar German states for a short time canvassed outstanding prewar modernists such as Otto Dix.8 For a few years art exhibitions served as a realm of cease-fire and included artists of all the occupied zones.

When the Cold War began with the blockade of West Berlinin 1948 and climaxed in the Korean War in 1950, the idea of a German-German artistic community proved to be unrealisable. It was not only the West German authorities (political as well as aesthetic) that preferred East German art to be excluded; the East German authorities also wanted their artists to stay at home – and in East Germany political and aesthetic authorities tended to be one and the same. So the early dOCUMENTA exhibitions represented not so much a new postwar era as the tensions of the Cold War.

Recklinghausen

Looking at the first dOCUMENTA in a specifically German context provided another surprise: only recently I realised that I count among the dOCUMENTA addicts who tend to exaggerate its singularity. In its historiography dOCUMENTA is seldom seen in the larger context of its time but is regarded as a unique event, a stroke of the genius of Arnold Bode, which it was in many ways but not without antecedents. To reconstruct dOCUMENTA’s prehistory in the context of the postwar German and European art scene is work still to be done and might lead to levelling its singularity perhaps a bit.

At least, I have suspected this ever since I did a lengthy interview with the West German curator Thomas Grochowiak for a book that has just been printed.9 Born in 1914, Thomas Grochowiak played an important role in the development of the postwar modern art exhibition inGermany and in re-establishing modern art there. From 1950 he was responsible for the annual exhibitions of the Festival of the Ruhr (Ruhrfestspiele), a festival in the city of Recklinghausen at the northern edge of the Ruhr region.

During the two postwar decades in West Germany his role was as important as that of Arnold Bode, though he never became as prominent in the historiography of exhibitions. It is little known, even in Germany, that the dOCUMENTA had a forerunner in this annual exhibition that was born as an extension of a theatre festival. The city of Recklinghausen had been home to the Ruhrfestspiele from 1947, the early years being devoted to opera and theatre only. The annual Ruhrfestspiele aimed to serve the population of the industrialised area around theRuhr, where rapid economic growth had not yet created a comparable cultural boom.

Begun by a workers’ union with a strong socialist ethos, the festival addressed the coalminers and steelworkers inRecklinghausenand neighbouring cities in the Ruhr area. While the theatre-dominated annual festival started in 1947, the regular art exhibition started as its offspring in 1950 and was organised in a repurposed air-raid shelter.

In the early period these exhibitions were as important as dOCUMENTA, founded five years later but never acquiring a catchy title. Recklinghausen never received the international fame that documenta and the Venice Biennale achieved but it was an important counterpart to the first dOCUMENTA at Kassel, and played an international role insofar as one of the most important postwar curators was involved from the beginning, the director of the Stedelijk Museum at Amsterdam, the great Willem Sandberg.

From the start the annual Recklinghausen shows were early examples of themed art exhibitions (thematische Ausstellungen), a category later made famous by Harald Szeemann. In addition, they also had an advanced exhibition design. The Recklinghausen experiments in staging art may have to be considered as models for the installations in Kassel, the original source being in any case Sandberg’s Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, augmented with local ingenuity.

Like Arnold Bode, who was born in 1900, Thomas Grochowiak originally was a painter. Before 1933 he earned his money in applied arts and after 1945 was at the start of a career as a modern artist, when he was commissioned to run the local museum in the city of Recklinghausen. As Grochowiak told me, Bode was a regular visitor of the annual exhibitions in Recklinghausen, like almost everyone interested in modern art in postwar Germany, before he invented documenta. Bode must have been one of the first to recognise the importance of the Ruhrfestspiele’s experiments in exhibition design and concepts. He is even said to have asked if he could be the guest curator of one of them before he started his own enterprise inKassel. This is of some historical importance as in Recklinghausen modern art was presented in a way that, through Sandberg’s influence, reflected aspects of the modernist displays of the Stedelijk before and after the Second World War. Sandberg (born 1897), however, was not the only source of inspiration. There was also the ‘junger Westen’, a group of young artists, of which Grochowiak was also a member, who in their commissions to design spaces at Recklinghausen experimented with the white cube and combined fine and applied art in an original way. It was plainly significant that the postwar innovators in methods of displaying art – Sandberg, Bode and Grochowiak together with his colleagues from ‘junger Westen’ – had originally been visually trained artists rather than art historically educated scholars.

Unlike Recklinghausen, dOCUMENTA did not combine applied and fine art, much to Bode’s concern, I would imagine. His indispensable companion Werner Haftmann, the chief ideologist of the first three dOCUMENTAs, appears to have insisted successfully on his rather traditional academic notion of art, restricting the exhibition to painting, the graphic arts and sculpture. dOCUMENTA was innovative in its choice of contemporary painters and sculptors but very conservative in its understanding of media, rejecting photography and film as artistic media and, above all, ignoring design and architecture with few exceptions. Being familiar with the ideas of the Bauhaus, Bode, Grochowiak and Sandberg were open to combining applied and fine art, but Haftmann was not.

Developed only eighty miles from Kasselin Weimarand only one generation before the first documenta, the Bauhaus’s innovations reached documenta only in relation to the methods of display and not the ideology of art itself. Only the sixth documenta, under the aegis of Schneckenburger and curated by Klaus Honnef, included photography as art in its own right in 1977; and only the eighth documenta, again under the aegis of Schneckenburger and curated by Michael Erlhoff, tried to correct the highly questionable division between applied and autonomous art.

If dOCUMENTA is often seen as rival of the Venice Biennale, which it somewhat turned out to be in the end, it seems that in the beginning the Biennale was not the major point of reference, maybe not even a marginal one. There was an internal German competition between Recklinghausen and Kassel to see which could establish modern art presented in a modern way. In fact, Grochowiak has stressed that for his generation – and therefore Bode’s, too – the Milan Triennale was much more attractive, up-to-date and influential in the postwar decade than the Venice Biennale. As a designer of commercial fairs Bode would have visited the Milan Triennale and studied the art on display and the display itself as closely as Grochowiak did and Sandberg, too.

Restricted internationality

The first dOCUMENTA had been a purely European exhibition. Among the 148 artists, only one, Alexander Calder, originated from outside Europe. The three other North American participants were German emigrés of a first or second generation: Josef Albers, Kurt Roesch and Lionel Feininger, the latter even listed in the catalogue as representing Germany. Among the 147 European artists Germany dominated with fifty-eight, including part-time immigrants like Kandinsky, followed by France with forty-two artists, a figure that generously included German immigrants Wols, Max Ernst and Hans Hartung. Italy came next with twenty-eight, England with only eight, Switzerland with six and Holland with just two artists. A rather surreal view of ‘art in the twentieth century’, the field the first dOCUMENTA claimed to cover.

Subsequent ddOCUMENTAs expanded their geographical focus at the same time they managed to restrict the time period covered. The next dOCUMENTA aimed to cover only ‘art after 1945’, but in so doing also included a large number of North American artists and thus extended its purview. In this, the second dOCUMENTA was following of course the transatlantic partnerships also prevalent in politics, the economy and culture. Expanding its focus in space and reducing it in time made the dOCUMENTA the international exhibition we know now: by 1964 it dedicated itself officially to contemporary art of just the last couple of years.

The second dOCUMENTA also adopted a wider vision of the arts. For it Werner Haftmann invented the enticing slogan of ‘abstraction as a world language’. Thus, documenta appeared to extend its geographical scope to include the whole world, in much the same way as the then very successful artist Victor Vasarely spoke of abstraction as a ‘planetary folklore’.10 But whoever thought that the slogan would lead to more non-European artists being invited to Kassel would have been disappointed: the slogan was not intended to upgrade non-European art but rather to offer a licence for the latest Western recipe for art to the rest of the world – without any guarantee of imports from countries outside the transatlantic alliance. Thus, with very few exceptions, artists from Africa, Asia, Australia and South America remained excluded and were clearly under-represented in the so-called ‘world exhibition of art’ for over thirty years until the 1990s. Only the number of North American artists increased considerably from 1959 onwards. With its invitation to US artists documenta half-heartedly gave up its Eurocentric image of the world only to put in its place aNorth Atlantic one.

This was also true of the internationally renowned exhibition Westkunst (Western art) which Kasper König and Laszlo Glozer organised in Cologne in 1981. The title was a frank expression of what had not been spoken of until that moment: the predominance of the transatlantic art business, where only home-grown artists were regarded as relevant. Westkunst handled this so nonchalantly that it provoked a Yugoslavian curator to ask whether you had to be a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) to be exhibited under the Westkunst label. You could have asked this question about the first documentas, too.

The exhibition title, Westkunst, had been intentionally provocative in providing a handy concept for a somewhat complicated and also rather embarrassing fact: Europe may have exported the art museum as a cultural model throughout the world, but it was still reluctant to accept in its own art museums objects produced as museum-worthy art in non-European cultures. That was the stance of documenta for a long time, changing noticeably only in 1997 with dOCUMENTA 10. dOCUMENTA began as a self-help enterprise, to remedy a gap in public knowledge and evaluation of modern art after a period of censorship and attack in a war-destroyed country. Rather than even attempting to bring world art to a small provincial town, it could have seen itself as a good model for other places in the world to copy. For my own part, I feel it is open to question whether art can be understood worldwide and in any place, and wonder whether this is just a curatorial myth.

The universality of art

Although the first dOCUMENTA was reluctant to include non-European artists, it was surprisingly international in its pedagogical ideology. In the very first room, through which all the visitors had to pass, a series of photographic posters showed images of archaic and exotic sculptures. Photographs of works from Benin and pre-Columbian America were assembled there, as well as of works from archaic Greece and Mesopotamia, making the most heterogeneous look similar. Modern art was thus enhanced by other cultures and traditions, even by the most remote in time and space. (I have dealt with this special room extensively in my already mentioned essay, ‘Degenerate Art and documenta 1’).11

Arnold Bode, who planned this introduction to the exhibition, did not suggest anything of the baroque imperialism of the chamber of curiosities; instead, he wanted to refer to the taste for the exotic among early avant-garde artists. This intercultural reinforcement was based on the then fashionable theory of the universality of art. A product of the early twentieth century, this theory reached its apogee in the influential anthology Towards Modern Art or King Solomon’s Picture Book, published in London in 1952 by the Austrian emigré Ludwig Goldscheider.12 It intended to prove the continuity in expressive forms, from the archaic to the modern, from the earliest stone idols to Brancusi’s abstraction, from the Stone Age to Picasso. The theory of the universality of art had spread like wildfire with the worldwide success of the art museum, in which the European notion of art was globalised. InKassel, of course, it had a special aspect, directed, as it was, against classicising aesthetics as misused by national socialism. In its recourse to the idea of a continuity of expressive form in global and historical terms, the entrance hall installation cited so-called primitive and archaic art as a source of inspiration of modern art, not as a proof of aesthetic equality.

Kassel and Münster

Leaving aside comparisons with the Degenerate Art and the Recklinghausen exhibitions, I have also focused on two other aspects of documenta – its position in relation to art in the urban sphere and its attitude towards electronic media.13

The subject of publicly sited art arose with the 1959 dOCUMENTA 2, when the ruin of the Orangerie was found to be an attractive area. Subsequent documentas have taken different approaches, some concentrating on art inside the walls, as in Szeemann’s dOCUMENTA 5, others conquering the public sphere of Kassel, as in Schneckenburger’s dOCUMENTA 8. For this and many other reasons it is worthwhile to compare the history of documenta with that of another internationally renowned German exhibition, Skulptur-Projekte Münster, which for many reasons I have been familiar with from the very start in 1977. I visited the first exhibition by chance; I was teaching art history at the Polytechnic in Münster during the second in 1987, when during the exhibition I organised the international conference Unerwünschte Monumente. Moderne Kunst im Stadtraum (Unwanted Monuments. Modern Art in Urban Space);14 and I wrote the main catalogue essay, as well as the visitor’s guide for the third, in 1997; for the fourth, in 2007, I was a mere tourist again.

Begun in 1955, dOCUMENTA had a four- and then five-year cycle. Started twenty-two years later, Skulptur-Projekte Münster follows a comparatively modest ten-year cycle. The differences between both enterprises are obvious to anyone who ever visited them, but both have more in common than one might expect. Originally, neither was intended to be repeated on a regular cycle. The very first dOCUMENTA did not know it was the first, and only received its number 1 in retrospect. At Münster the first exhibition which was later labelled ‘Skulptur Projekte’ was simply called project area (Projektbereich) when it was decided in 1977, more or less at the last minute, to be added as an urban expansion to a museum exhibition on the history of modern sculpture that had already been planned for a long time by Klaus Bußmann. A Münster-born friend called Kasper König (younger brother of the already mentioned Cologne art-book dealer Walther König), who had lived in America for a couple of years and was one of the very first known freelance curators, encouraged him to include open-air projects by his friends Claes Oldenburg, Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Michael Asher, Bruce Nauman and Ulrich Rückriem. This is typical of both exhibitions again: both were initially conceived as minor additions to a more major event that had been planned over a longer period. In Kassel, dOCUMENTA was added to a state-funded and nation-wide garden festival (Bundesgartenschau). Originally, the art exhibition was going to be housed in a large marquee. That the ruin of the classical Museum Fridericianum was used in the end as an auratic backdrop to the international exhibition of twentieth-century art was due to a genial improvisation of money and means that made Arnold Bode famous as one of the great exhibition wizards of the century.

Thus, skilful improvisation lay at the heart of both exhibitions, with the caveat that it was easier, technically speaking, to site a few sculptures in the open air in 1977 than to refurbish the ruin of the Museum Fridericianum for pieces of art that needed to be protected from heat, dust and humidity. But it was, of course, as difficult for Skulptur-Projekte Münster as it was for dOCUMENTA to legitimate the use of public money for contemporary art, especially in Münster where the pieces were situated in the public spaces of the town. In fact, as extensions of another event, they were originally regarded as necessary to make good a deficiency in knowledge of contemporary art. In case of dOCUMENTA, this lack of knowledge might be thought self-evident given the Nazis’ policy of persecution and confiscation, but the situation was a little more complex than that and slightly different. In the 1930s there probably was not another nation that was as well informed about modern art as the German nation because the various propaganda exhibitions, notably the Munich exhibition Degenerate Art showed a large number of modernist masterpieces, albeit in an unfavourable context, and allegedly had millions of visitors in several major cities. The task of dOCUMENTA was thus less to inform the German postwar public about modern art but to re-evaluate it, which of course meant providing information about the development of international art during the twelve years when Germany was cut off from international contacts. This was part of the Allies’ efforts at re-education, a word incorporated into German since then. In 1977 the situation in Münster was not so different, and the re-evaluation of modern art also was an aim. But the cause was different and more local in character. Since the 1950s modern outdoor sculptures had been the focus of conflict in the conservative Westphalian town of Münster. The donation of a Henry Moore to the local university in the 1960s, for example, had been rejected. In the mid 1970s the purchase and installation of a relatively well-behaved kinetic outdoor sculpture by George Rickey provoked more letters of protest, prompting Klaus Bußmann to conceive of a major museum exhibition of modern sculpture to address the gap in knowledge and taste among his fellow citizens. Bußmann planned to include some outdoor pieces but only in the immediate environs of the museum, on its very premises in fact. James Reineking, for example, sited a sculpture prominently in front of the museum entrance. Such spaces are what the German curator Claudia Büttner has correctly baptised ‘institutional space’ in her 1997 book Art Goes Public: Von der Gruppenausstellung im Freien zum Projekt im nicht-institutionellen Raum (Art Goes Public: From Group Exhibitions to Projects in Non-Institutional Space). This important distinction between institutional and non-institutional spaces in art underscores the significant step outdoor modernist art had to take, namely, to be positioned in spaces that were not connected with official institutions of art.

This was exactly what Kasper König proposed to his friend Bußmann in 1977: the key innovation was to leave the museum grounds and its environs, and extend the exhibition of outdoor sculptures throughout the city. König’s slogan was ‘VomParkauf den Parkplatz’ (‘Out of the park and into the parking lot’). This was not the first instance of such a step, not even in Germany, but it was an apt response to the original local problem, the opposition to urban outdoor sculpture, that Bußmann had thought at first to make only on the premises of the museum only. Of course, König hit a nerve among the brave citizens of Münster, but he also hit the international headlines, too. In fact, the local politicians were impressed when the name of their provincial town appeared on the front page of the New York Times in a favourable context, and they were thus keen to discuss a follow-up of the show, even though it had met with hostile comments in the local press.

It was not coincidental that Kasper König had taken the opportunity to operate in Münster. The Westphalian exhibition opened at the same time as the sixth dOCUMENTA in Kassel. Having been a co-curator of documenta 5 in 1972 – the famous one that Harald Szeemann had been responsible for – König could have thought himself a serious candidate for the curatorship of the next show in 1977 but he was not selected. The coincidence of the opening of the two exhibitions at the same time allowed an element of competition. The curators in Münster took the opportunity to address a theme of which dOCUMENTA had always been very timid, that is, modern art in the urban sphere.

dOCUMENTA and Skulptur-Projekte Münster also have in common that originally and for several iterations they were organised by two co-operating curators, who complemented each other perfectly in many respects. In both cases one of them was locally based with an supra-regional reputation (Bode in Kassel, Bußmann in Münster) and the other with an international background (Werner Haftmann had lived in Italy for a couple of years during the Third Reich in the case of dOCUMENTA, and Kasper König had lived in Halifax and New York in the 1960s and 1970s in the case of Münster). The case of König is interesting because he had been born in Münster, in a well respected and well connected family. Thus, both the Münster curators had a strong local base. The local roots of Bode inKassel and of Bußmann and König in Münster were fundamentally important for the longevity of the exhibitions.

The dOCUMENTA pair of Bode and Haftmann had worked with changing committees but remained the centre of power until Haftmann quit following the third documenta in the late 1960s to become director of the Neue Nationalgalerie in West Berlin. Bode tried to preserve his shrinking influence in his remaining years until his death in 1977 after dOCUMENTA 6. In Münster Bußmann and König split only recently when Bußmann retired to Paris and König remained head of a small, new committee of local professionals (all female for the first time in the history of both exhibitions) to prepare Sculpture Projects for 2007. The collaboration of two curators with equal rights and competence is rather rare in this business: to appreciate this, it is only necessary to remember that Edy de Wilde and Harald Szeemann proved unable to work together on dOCUMENTA in 1987, which could have been a gem in the history of this periodic exhibition.

Both exhibitions brought world fame to small, provincial towns, which in turn proved to help make the exhibitions more visible than they would otherwise have been if in a bigger metropolis, where they would have had to compete with various other glamorous events. (This is true for Recklinghausen, too, and underlines the importance of cultural federalism with these German exhibitions.)

Most obviously, both exhibitions have in common the fact that despite their experimental beginnings they were repeated. Although planned in, and for, a very short time, they have surprisingly turned out to have a long life. While Bode had to make use of all his legendary persuasiveness to have dOCUMENTA repeated in 1959, the curators of the Munster project were even asked to consider cutting the ten year interval to five to fit in with documenta because of the international prominence it brought the town, a seductive offer the organisers were able to resist.

At the same time, the curators of both exhibitions had to address the classic biennale problem, that is, to discover and put into place a mixture of traditional structures and contemporary art, of a general concept and flexible ideas, of a reliable local infrastructure and changing international curatorships. While biennales have become ubiquitous, neither dOCUMENTA nor Skulptur-Projekte Münster face any direct competition, being seen now as town-specific.

In fact, it is interesting to see the titles under which the only serious attempts to challenge the singularity of dOCUMENTA have been made within Germany: Zeitgeist (1982) and Metropolis (1991) were exhibitions made by Christos Joachimides and Norman Rosenthal for West Berlin, both exhibitions without any doubt planned to break the monopoly of documenta with great shows of contemporary art in a capital city. With both titles Joachimides explicitly challenged the predominance of documenta, the first, Zeitgeist, putting the up-to-dateness of dOCUMENTA into question, the second, Metropolis, trying to outclass the provincial town of Kassel with the historical urban myth of a Berlin that, however, had yet to recover from the last war and the ensuing division of the city. Joachimides could not establish a Berlin tradition to challenge Kassel or Münster. Berlin is famous for contemporary art today but this is owing to its newly established biennales and art fairs, the latter having become the true opponent to every periodic exhibition of contemporary art, and challenging more and more the institutional and independent curatorial function of biennales. Art fairs represent growing competition for dOCUMENTA, too, because they are annual – the oldest type of periodic art exhibition since the age of guilds and the early academies.

As I pointed out at the beginning I rather stumbled onto my subject, the history of exhibitions, when I first visited the dOCUMENTA archive in 1981. So I was amazed to see that in 1997 the idea of the archive played a role in the documenta curated by Catherine David. During the 1980s the notion and image of the archive had become rather popular among intellectuals, owing to the idiosyncratic use Michel Foucault had made of the term in his political anthropology. Now the archive was no longer regarded as the dull and boring working place of pale and faded clerks but a solemn post-structuralist notion.

In 2007 Skulptur-Projekte Münster included its own archive, too, by presenting table tops used for previous projects in 1977, 1987 and 1997 as well as photographs of their installations and by inviting the artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster who contributed a wonderful open-air retrospective of the preceding three exhibitions with key works she carefully and wittily recreated in miniature and sited on an open meadow. Thus, both exhibitions have included their own history, either in a catalogue, as Catherine David preferred, or as a museum installation and an art work as in Münster in 2007. It took the dOCUMENTA forty-two years to include its history and Skulptur-Projekte Münster only thirty. The historiographic gap mentioned at the beginning is in fact diminishing.

Coda

Periodic exhibitions seem to be the oldest form of showing works of art, established some time before crafted items of beauty or excellence were regarded as art objects. Before the academies of art began to organise more or less annual exhibitions of art (in Paris from the middle of the seventeeth century), regular exhibitions were a monopoly of the guilds. Until their monopoly was threatened by the academies, only the guilds were allowed to offer artisan products at fairs, the dates of which followed the Christian calendar and thus were regular, too. The competition between the guilds and the art academies can be regarded as the beginning of the art exhibition in general, as the German scholar Georg Friedrich Koch pointed out 1967 in his book Die Kunstausstellung. Ihre Geschichte von den Anfängen bis zum Ausgang des 18.Jahrhunderts, (The Art Exhibition. Its History from the Beginning to the End of the Eighteenth Century).

It seems that periodic exhibitions have not only been the oldest but also the most successful model of art mediation. Their repetition gave them importance, attention and resonance. The most successful form of a periodic exhibition of modern art is 113 years old now: the Venice Biennale – a success story from the start that has led to many imitations, no matter that the formula was used for architecture, music and film, that the events took place in São Paolo, Shanghai or Ouagadougou, or whether they were baptised Manifesta, Ensemblia or Fespaco. Especially in recent decades the biennale concept has spread worldwide and acquired such an omnipresence that artists can in fact travel for years to ‘one place after another’ (Miwon Kwon) with their reputedly site-specific concepts in store, while critics complain that the recent boom in biennales has given birth to an art that should be labelled ‘biennale art’. I prefer to see it as a new type of concept art that could be called ‘event specific’.15 In any case, it is interesting to see that it took the Venice Biennale more than sixty years before the topic of its history came to the fore with the already mentioned book by Lawrence Alloway, The Venice Biennale 1895–1968. From Salon to Goldfish Bowl. Periodic exhibitions provoke a consciousness of their own history, but it obviously takes time before the topic is taken care of.