My interest in the subject of biennials and their participants’ national affiliations dates back to the Taipei Biennial of 2004, the fourth such event in our city, and my reaction to a curatorial provocation there. I had been kept waiting for more than three hours for what turned out to be a crisp thirty-minute interview with one of the two curators of the show, the Brussels-based Barbara Vanderlinden. I kicked off by asking her to explain the curatorial policy regarding the number – five – of native Taiwanese artists chosen to appear. To this she replied by curtly throwing a question of her own back at me: ‘Do you know how many Taiwanese artists were represented in the Shanghai Biennial?’ Meaning, of course, that five local representatives seemed to her quite adequate, thank you very much, and people would certainly be wrong to expect more.1 Her reply took my breath away. I had no comeback at the time – not only because I did not know the answer, but also because I felt I was speaking to a foreign expert who knew her own business better than I did. In those days I enjoyed neither the funds nor the working conditions to enable me to travel long distances to biennials, as global art-world insiders apparently can. More recently, however, I have been able to fly to biennials as remote as Havana and São Paulo, as well as to most of the Asian and European events, and I find that the question of artistic representation at such international gatherings is still, after all this time, haunting me.

It may seem odd, even retrograde, to think of contemporary art practice in terms of artists’ nationality and place of birth, at a time when there is so much talk of globalisation, hybridisation, transnationalisation, world markets and so on. Nevertheless, the question of national affiliation is critical to what the biennial (or triennial, or quinquennial) has come to stand for since the 1980s. An increasingly popular institutional structure for the staging of large-scale exhibitions – some observers refer to ‘the biennialisation of the contemporary art world’ – the biennial is generally understood as an international festival of contemporary art occurring once every two years.2 Here the operative words are, of course, ‘international’ and ‘festival’. On the first of these depends the second: without the national diversity of its participants, there could be no real celebration or festivity. ‘International’ in this scheme of things means that artists, almost by definition, come from all four corners of the world; even events with a specific geographical focus, such as the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale, cast their net far beyond their immediate backyard; they rightly see this as imperative not only for their legitimacy but also for their success.

Artscapes

The fact that artists from remote areas now appear centre-stage in Western events such as the Kassel documenta or the Venice Biennale is often taken as further proof that the distinction between centre and periphery has collapsed. In his studies of global cultural flows, for example, Arjun Appadurai uses the terms ‘artscape’ and ‘ethnoscape’ to characterise the space through which uninterrupted flows of people – including artists, curators, critics – and high art criss-cross the globe, as city after city vies to establish its own biennial in order to claim membership of the international art scene.3 Like other globalisation theorists, Appadurai emphasises the growing planetary interdependence and intensification of social relations. Nowhere, however, are we told in what directions such ‘flows’ flow, nor what new configurations of power relations these seemingly de-territorialising movements imply.4

Hence this attempt to understand the power implications of biennials by looking more closely, and empirically, at the artists themselves – a luxury in which most theorists have too little time to indulge. I am, of course, well aware of the risks that a nation-based approach may involve, including the possibility of inviting criticism from the pro-globalisation lobby in particular. I do not wish to assert that the international art scene has not undergone significant changes over the last two decades. But what ultimately is the nature of these changes, and for what reasons have they taken place? Is the much-discussed collapse of the centre and dissolution of the periphery as irrefutable as some people would have us believe? Has the global art world really become so porous, open to all artists irrespective of their origins – even if they come from what Paris or New York would consider the most marginal places?

To attempt to answer these questions on the basis of national statistics may be unexpected. But the actual numbers of artists, and the range of countries they come from, prove to be centrally embedded in the psychology of biennial organisers and feature prominently in their marketing strategies. The 2006 Singapore Biennial boasted of ‘95 artists from over 38 countries’, while at the Liverpool Biennial in 1999, ubiquitous banners proclaimed: ‘350 artists, 24 countries, 60 sites, 1 city’. In what follows, I shall take a closer look at the quantitative data underpinning such ‘flat-world’ claims, by establishing not only where the artists come from, but also, in the case of those who move or emigrate, which places they choose to emigrate to – in other words, the direction of the cultural flows they personify. My purpose in examining these data was, firstly, to map out the shifts that have taken place in the focus of large-scale international exhibitions, which have gone from a marked Eurocentrism to encompass the world beyond the NATO-pact countries; and secondly, to ask whether these events have become another powerful Western filter, governing the access of artists from under-resourced parts of the world to the global mainstream.

In order to provide a long-term view of these developments, I shall focus here on the Kassel documenta exhibitions, nine in all, between 1968 and 2007; examining firstly, where the artists were born; secondly, where they are currently living; and thirdly, the relation between the two.5 I use typical regional categories – North America, Latin America, Asia, Africa and Oceania. Europe, however, I have divided in two. For despite EU enlargement, there are still two Europes in contemporary art practice: one comprises Germany, Italy, Britain, France, Switzerland, Austria, and to a lesser degree Holland, Belgium and Spain, which supply the majority of European art figures – ‘Europe A’. The remaining countries, whose artists appear only sporadically at international events, form what I call ‘Europe B’.

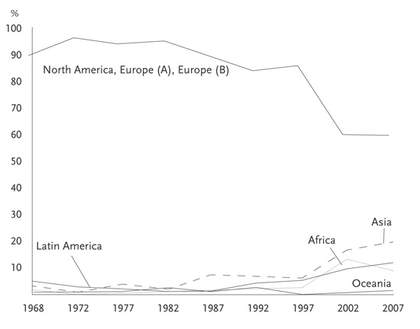

What conclusions, then, can we tentatively draw from this mass of statistics, which seems to belong more to sociology than to art history? The first and most obvious is that until recently, the vast majority of artists exhibited at documenta were born in North America and Europe – well over ninety per cent in fact, reaching a record ninety-six per cent in 1972 (see table 1). Although the 1989 Magiciens de la terre exhibition at the Pompidou Centre is generally considered the first truly international exhibition and a trend-setter for the next decade, North Americans and Europeans were still predominant at the 1992 and 1997 documentas. The real change came with Okwui Enwezor’s documenta 11 in 2002, when the proportion of Western artists fell to a more respectable sixty per cent. It remained fixed at this lower level in 2007.

Table 1

Where documenta artists were born

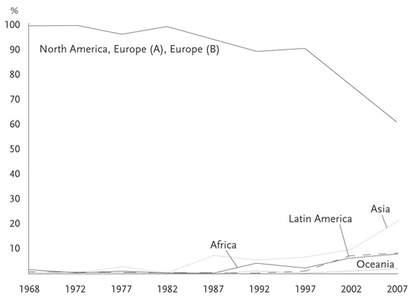

The figures on where artists are currently living, meanwhile (see table 2), show that a substantial number of artists have moved or emigrated from the countries where they were born. In some cases, of course, artists will divide their time, and their lives, between two or more places – their birthplace, and where their artistic careers take them (or where they have a better opportunity of succeeding). Up to and including the 1982 documenta, nearly one hundred per cent of participating artists lived in North America and Europe. This proportion begins to fall from 1987; for the 1992 and 1997 documentas it was around ninety per cent, dropping to seventy-six per cent in 2002 and sixty-one per cent in 2007.

Table 2

Where documenta artists are currently living

(Source: documenta catalogues 1968–2007)

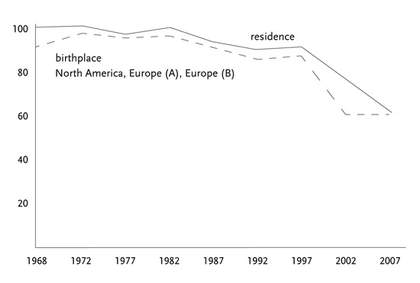

But it is the difference between these two sets of figures – where artists were born and where they are currently living (see table 3) – that interests me most, because it shows what directions artistic ‘flows’ have taken. Of course, artists do not move solely because of their work: there may well be personal circumstances involved; but there is no denying that an artist from, say, Taiwan or Indonesia stands a better chance of succeeding in the international art world if she lives in New York or London. Before 1992, nearly all the artists originally from Latin America, Asia or Africa had already moved to either North America or Europe before they exhibited in documenta. During the 1990s, these ‘flows’ represented around four or five per cent of the total artists showing. By 2002, they had risen to nearly sixteen per cent.

Table 3

Comparisons between artists’ birthplace and current residence

(Source: documenta catalogues 1968–2007)

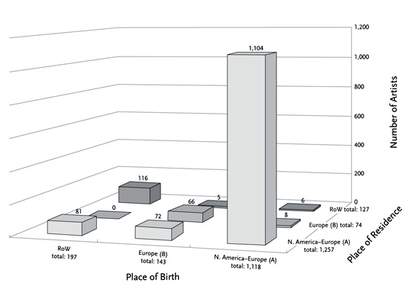

As table 4 demonstrates, the upshot of these movements is unmistakable. For artists born in North America and Europe A, nearly ninety-three per cent of movements are within that region – between London and New York, for example, where the conditions for artistic production and reception may be considered more or less equal. Secondly, for artists born in Europe B, nearly eighty-nine per cent of movements are towards North America and Europe A, presumably in search of better support systems and infrastructures. Thirdly, for artists born in Latin America, Asia or Africa, the overwhelming majority of movements – over ninety-two per cent – are to North America and Europe A. They constitute a generalised one-way emigration from what I would call the periphery to the centre, or centres; that is, in the direction of the USA, UK, France and Germany. As we can see, seventy-two artists from Europe B and eighty-one artists from the rest of the world have moved to North America and Europe A, making this region the most popular place of residence for the majority of the artists who have figured in the last nine documentas. Rarely if ever does an artist from London or New York move to, say, Thailand or Trinidad.

Table 4

Migration of documenta artists 1968–2007

(Source: documenta catalogues 1968–2007)

Flowing uphill

There is a Chinese saying: water flows downhill, people climb uphill. If, as some critics would have us believe, centres and peripheries are a thing of the past, how are we to account for this almost exclusively one-way flow of artists? Figures like this lead us to question claims that the 2002 documenta 11 represented ‘the full emergence of the margin at the centre’,6 or ‘the most radically conceived event in the history of postcolonial art practice’, offering ‘an unprecedented presence of artists from outside Europe and North America’.7 Whatever questions may be raised by the hybrid make-up of the emigrant artists in question, there is something highly incongruous in talking about an exhibition like documenta 11, in which nearly seventy-eight per cent of the artists featured were living in North America or Europe, as illustrating ‘the full emergence of the margin’.

Although it is forever shifting, the global art world nevertheless maintains a basic structure: concentric and hierarchical, we can imagine it as a three-dimensional spiral, not unlike the interior of the Guggenheim in New York. Concentric because there are centres, or semi-centres, and peripheries as well. To reach the centres you need to imagine an uphill journey, starting from the peripheries and passing through the semi-peripheries and semi-centres before you reach the top – though in some cases it may be possible to jump straight from a periphery to one of the centres. Hierarchical because, like all power relations, the spiral has a central core, with clusters of satellites orbiting it. Even those who champion the globalisation of the contemporary art world, and imagine the biennial to be one of its most successful manifestations, recognise a political dimension to such exhibitions. Okwui Enwezor, for instance, has advocated a ‘G7 for biennials … so as not to further dilute the “cachet” of this incredibly ambiguous global brand’.8 Global the biennial perhaps is, but global for whom and for what reasons? Whose interests are served by the ‘biennialisation’ of the contemporary art world?

The rise of the biennial over the last twenty years has, of course, made it easier for a few artists from less well-resourced countries to gain visibility in the art world. If, however, this is indeed part of ‘globalisation’, it is very different from other manifestations of that process. The agents of economic globalisation, for example, whether individuals or multinationals, have to invest substantial amounts of time and money in order to establish themselves in their new location. The people who curate most of the biennials these days, on the other hand, are constantly on the move. Jetting in and out of likely locations, they have no time to assimilate, still less to understand, the artistic production in any one place. From the viewpoint of those living and working in distant outposts, mega-curators and global artists may seem well connected; but they remain, by the very nature of the enterprise, more or less culturally rootless. At the same time, this deracination gives them a position of advantage, if not of privilege; for them, biennials do indeed have no frontiers. But for the majority outside the magic circle, real barriers still remain. The biennial, the most popular institutional mechanism of the last two decades for the organisation of large-scale international art exhibitions, has, despite its decolonising and democratic claims, proved still to embody the traditional power structures of the contemporary Western art world; the only difference being that ‘Western’ has quietly been replaced by a new buzzword, ‘global’.