Little could be more antithetical than the premises of the two most contentious European exhibitions of 1989, Magiciens de la Terre at the Centre Georges Pompidou and La Villette, Paris, and The Other Story in London’s Hayward Gallery. A mix of Western gallery art and folkloric art from the global elsewhere, Magiciens, curated by museum director Jean-Hubert Martin, pursued the anthropological notion of pre-modern cultural ‘authenticity’ in which intercultural aesthetic borrowing by the non-European was perceived as illegitimate ‘contamination’; whilst The Other Story, curated by the artist Rasheed Araeen, sought to demonstrate and legitimise the suppressed history of a modernist aesthetic among British visual artists of African, Caribbean and Asian ancestry.1 If Magiciens was instrumental in drawing global cultures into the orbit of Western institutions, initiating a ‘postmodern’ wave of neo-imperial ‘explorations’ of the exotic, the somewhat ironically titled The Other Story was understood internationally, if not domestically, as a major breakthrough in ‘de-imperialising’ the institutional mind.

Couched as a ‘celebration of achievement’, Araeen’s catalogue text leaves us in no doubt that the absence of Black and Asian artists from the history of British modernism and national patrimony could only be attributed to racist discrimination. Guy Brett’s catalogue essay suggested this exclusion was symptomatic of a wider malaise in the British art establishment, which he describes as ‘an antiquated and still basically beaux-arts model’ that consistently failed to recognise the experimental and transnational in its midst.2 Indeed, in the absence of institutional support, it is common to find experimental artists acting as their own exhibition curators, writers, historians or archivists, and this was also true for the generation of Black and Asian artists that emerged in the 1980s. (Note that ‘Black’ at this time was a self-defining political not phenotypical category, alluding to alliances based in shared histories of colonial repression.) Thus, The Other Story was one of several multi-stranded initiatives by Araeen and other artists to construct a cultural and archival counter-memory.3

Araeen must be credited as the only commentator persistently to draw attention to the need for British Black and Asian art historical research at a time when, on the one hand, artists were being categorised either by ethnicity or by socio-political concerns that distracted from the material, historical and philosophical evaluation of their work proper to the discipline of visual art; and on the other, public funding for so-called ‘ethnic minority arts’ primarily meant the ‘folkloric’ or ‘community arts projects’. First proposed to but rejected by the Arts Council in 1978 as being ‘untimely’.4 The Other Story perhaps may never have happened were it not for the pressure exerted on art habitus gatekeepers during the 1980s by the generation of artists now known as the British Black Arts Movement, politically radicalised by feminist critique and anti-racist discourses in the UK, the USA and South Africa. This movement included Araeen himself, who is a bridge between those artists who witnessed the turmoil of national liberation and civil war following decolonisation, and the later generation schooled in semiotics and the politics of representation. Intellectually, he bridges Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (1952), revisited by postcolonial theorists for its focus on the psychic dynamics of ‘race’, and Wretched of the Earth (1961) by the same author, which was a major influence on anti-colonial debates.

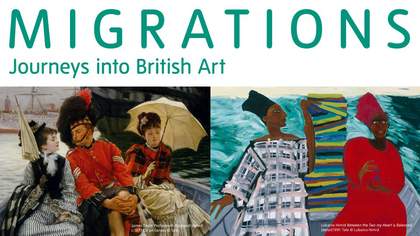

Fig.1

Sonia Boyce

‘Lay back, keep quiet and think of what made Britain so great’ 1986

Charcoal, pastel and watercolour on paper;four parts

each 152.5 x 65 cm

© Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

Of the twenty-four artists in the exhibition, only six were drawn from the younger generation, which included the only four women: Sonia Boyce (fig.1), Mona Hatoum, Lubaina Himid and Kumiko Shimizu.5 Among the more analytic exhibition reviews, the poor representation of women artists drew the most criticism, not ameliorated by Araeen’s apologia regarding his inability to locate Black and Asian women artists from the earlier generations and the refusal of several women to participate in what they possibly feared was a ghettoising context.6 Among the supportive reviews, Petrine Archer-Shaw complained that the exhibition reflected none of the vibrancy of Black vernacular cultures, film and music.7 However, this was not Araeen’s curatorial remit; his criteria for selection were strictly focused on the relationship between modernism in the visual arts and African, Caribbean and Asian artists resident in the UK for at least ten years, with the aim of interrogating how certain practices, barring a few isolated cases, had become not simply marginalised but ‘whited out’, as it were.

One apparent paradox in the discourse of The Other Story was the implied desire for inclusion in and approbation from a system regarded at the outset as unjust and corrupt. This is a paradox inherent in ‘oppositional’ politics where the opposing position tends, among other things, to be a reactive response to an existing authority that thereby maintains its status as the privileged term. I shall try to address this by placing my focus where Araeen really places his – on the practices of the immediate post-war generations rather than those of the Black Arts Movement, at the time itself largely unaware of its predecessors for the very reasons advanced by The Other Story.8

I shall pursue two lines of thought prompted by a retrospective consideration of the exhibition’s context: modernism and intellectual property, and nationalism, internationalism and cosmopolitanism.

Modernism and intellectual property

One fundamental argument is that African, Asian and Caribbean modernists presented an untenable challenge to a Eurocentric universalist system of values to which, nonetheless, only the white (male) artist could claim legitimate genealogy. (To even speak of ‘genealogy’ is to invoke the spectre of ‘race’ and belonging.) In other words, this ‘universalism’ was defined by what it excluded. During the early 1980s, modernism was still being portrayed as a European innovation with no influence from other cultures other than stylistic ‘affinity’, as the curators of the 1984 MoMA exhibition ‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art: Affinities of the Tribal and the Modern described the relationship between early European modernism and so-called ‘tribal’ cultures. As Terry Eagleton put it, non-Western others had ‘culture’ – irrational, pre-modern and static, whilst the West had ‘civilisation’ – rational, modern and progressive.9 The violence of Eurocentric universalism (or better, universalised particularism) lies both in its evolutionist systematisation of other cultures, whereby, as Araeen stated, ‘other cultures/peoples [were removed] from the dynamics of historical continuity’,10 and in its subordination and devaluation of cultural difference to its own privileged terms of reference.11

However, from a ‘postcolonial’ perspective, European modernity itself was a consequence of the wealth, power and knowledge accumulated through slavery and imperial exploitation. Contact between Europe and its ‘others’ produced transformations in both directions, leading to a plurality of modernities and modernisms, each with its own local inflections – what Partha Mitter, speaking primarily of the situation in India, calls ‘virtual cosmopolitanism’.12 Thus, contrary to the view that Western art followed a self-generating intellectual and aesthetic progression – with the occasional ‘affinity’ – cross-cultural encounters are perceived as central to the formation of modernism, not supplementary (unless in the Derridean sense of the supplement already contained by what it amplifies), both in the formal break with pictorial conventions and in the development of the ‘expressionist’ strand of modernism that began with ‘primitivism’. This is the umbilical connection made by Gavin Jantjes in his painting Untitled, 1989, among the key artistic statements in The Other Story.

Alongside its technologies, the British Empire also (inadvertently) exported the Enlightenment’s principles of equality and freedom, patently at odds with colonial tyrannies: democratic rights were hardly universal if they only applied to a select few. Hence by the early twentieth century one sees emerging in the colonies the twin aspirations of national independence and modernism in visual art, both responding to prevailing socio-political realities and signifying the early optimism of modernisation. To illustrate the complexity of colonial intercultural exchanges, the artist Everlyn Nicodemus, in speaking of the African context, points out that for the African artist the academic naturalism of European easel painting was ‘modern’ and its own sculpture ‘traditional’, whereas for the European the position was reversed.13

Ronald Moody

Johanaan (1936)

Tate

In the British context, however, the most important Black artist in London of the interwar decades was Ronald Moody (1900–1984), who, although he arrived in 1923 from Jamaica to study dentistry, was so overwhelmed by the Egyptian collection in the British Museum (1929) that he turned to sculpture (fig.2).14 During the same period Henry Moore also frequented the British Museum, in his case drawn by Mayan sculpture. Hence, as Araeen points out,15 both artists occupied and responded to a common spatio-temporality and artistic ethos belonging to the history of British modernism.

However, The Other Story effectively begins from the first post-war decades, with the generation of African, Asian and Caribbean peoples recruited to aid in the reconstruction of Britain. In 1949, a year after the Empire Windrush docked in Tilbury, what had originally been the Commonwealth of Nations under the colonial British Crown was reconfigured as the Commonwealth of Independent Nations. Amongst its mandates was educational, cultural and economic exchange, and the Commonwealth Institute became an important exhibition venue.16 Throughout the 1950s and 1960s many artists and writers from the Commonwealth also came to Britain to study or work; they gravitated to what they considered to be the intellectual and artistic centre of modernism, just as artists earlier had congregated in Paris. Many of the participants of The Other Story studied in prestigious British art schools and therefore, contrary to the dismissive claims made by later critics, were visually and intellectually literate in prevailing debates on modernism and academicism.17

Initially, this ‘Commonwealth’ generation of artists had modest recognition and support from galleries and critics independent of the cultural events staged by the Commonwealth Institute. Amongst the most welcoming were Victor Musgrave’s Gallery One, which exhibited Francis Souza and Avinash Chandra; the Woodstock Gallery, exhibiting Moody and Uzo Egonu; and the New Vision Centre, set up in 1958 and directed by the South African artist Denis Bowen with Kenneth Coutts-Smith whose interest in international non-objective art included alongside European Tachist, Kinetic and Constructivist art, Aubrey Williams, Ahmed Parvez, Amwar Jalal Shemza, and Balraj Khanna. But as discrimination and hostility against immigrants within British society increased, so aspirations of being fully recognised by the art establishment diminished. Some artists returned home; others, like many white artists, relocated to New York as the new centre of artistic energy; whilst others like Egonu remained quietly working in Britain. Williams, Moody, Clifton Campbell (who eventually returned to Jamaica) and Althea McNish found intellectual and politically focused support in the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM, 1966–72), although they were disappointed by its lack of appreciation for visual arts.18 CAM was primarily a literary and publishing collective with sympathetic links to the US Civil Rights Movement and the Black Panthers; nowadays the list of its participants reads like a ‘Who’s Who’ of internationally distinguished poets and writers.19 This contrast between sustained recognition in the literary, film or music field and that in visual arts is profoundly dispiriting, an indictment in itself of the structures of support available to art and artists.

Among the reasons why the ‘Commonwealth’ generation dropped off the radar during the 1970s, one can suggest the following: by 1973 the British government appears to have lost its enthusiasm for the Commonwealth as an economic and cultural market and joined the European Community. At the same time, as Britain increasingly identified itself politically with the USA, one cannot discount the impact on British art of the aggressive promotion of American art and consumerism during the Cold War.20 In addition, by now, interest in those strands of modernism rooted in ‘primitivism-expressionism’ had waned, as artists turned to alternative practices intent on challenging institutional orthodoxy.

Obviously, shifts in the artistic climate may ‘explain’ why certain art practices go out of fashion, but not why they are absent from public collections, art historical anthologies and exhibition surveys. For The Other Story the seeds of this exclusion were to be found in the extent to which the reception of the ‘Commonwealth’ generation was entangled in patronising attitudes increasingly inscribed with racist undertones of cultural nationalism and separatism. Araeen’s catalogue text cites numerous instances in which, pursuing a rhetoric of stereotypical cultural assumptions, earlier critics, much as the later ones, contextualised the work by the artist’s ethnicity, not by the prevailing – albeit Eurocentric – criteria of modernism. For instance, Chandra aligned his work to van Gogh and Soutine, and so was insulted to be asked if he could paint elephants and tigers.21 Whilst Williams claimed influences from the New York School, especially Gorky, alongside Guyana’s pre-Columbian Indian iconography, one reviewer, after alluding to ‘tangled forests and African rituals’, stated that ‘[Williams] has become more acceptable to European eyes but less powerful, though some of the original primitive urgency remains’.22 It is important to note that Williams supported modernist ‘abstraction’, which he saw as consistent with pre-modern traditions, against narrative painting, which he regarded as ‘missionary art’.23 Meanwhile Khanna’s work was described as ‘suffused with a purely Indian sensibility … imbued with an element of sensuous charm natural to his native tradition.’24 Perhaps the most ‘honest’ comment was the one addressed to Frank Bowling: when he was not selected for the Whitechapel’s New Generation exhibition of 1964 alongside his Royal College peers, he was told that ‘England is not yet ready for a gifted artist of colour.’25

That such attitudes still prevailed in the late 1970s and early 1980s is confirmed by comments made by the second generation Black and Asian artists about their art school experiences,26 and the institutional double standards applied to them, whereby the appropriation of global artistic capital was solely the prerogative of white artists. Modernism was the intellectual property of the European and they had crossed a forbidden line – they were trespassers, irrespective of their professional training. If earlier critics sought to stress ethnic roots, the accusation of cultural ‘inauthenticity’ was to be levelled in even more chauvinistic and vitriolic terms at The Other Story by newspaper critics. Thus, we find Andrew Graham-Dixon asserting that the work was ‘tame and derivative’;27 and Brian Sewell (the last man standing of the old ‘beaux-arts’ brigade) pronouncing that the works ‘parroted Western visual idioms they don’t understand’ as ‘third-rate imitations of the white man’s cliché’.28 One can only describe these arrogant, unsubstantiated opinions that commonly passed for ‘art criticism’ as themselves clichéd ‘parrotings’ of prejudice and ignorance. The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu points out that the power to ‘consecrate’ value that critics assign to themselves does not reflect a value intrinsic to art, but to the dynamics of competing interests in the field.29 Value is reflected not through the work of art as such, but through agents with a mastery of the rules of the game – rules that were more than transparent to the participants of the Black Arts Movement, new social agents at a remove from the earlier hierarchical colonial binaries.

Among the more ambivalent aspects of The Other Story was its complaint of exclusion from the institutions of national patrimony whilst conforming to their systemic rules, poised between a reactive critique of Eurocentric values and a proactive drive to create a new set of parameters for reading art history. The prevailing intellectual climate was dominated by the sociologically biased philosophy of ‘recognition of difference’, ‘redistribution of wealth’ and ‘equality of opportunity’. Whilst this constituted one of the most important anti-colonial attacks on British complacency, it tended, on the one hand, to obscure the fact that cross-cultural encounters produce difference; and on the other, to fetishise difference whilst downplaying those very commonalities Araeen’s discussion of modernism sought to demonstrate.

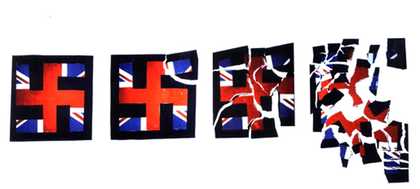

Genuine inclusion requires an institutional mindset prepared to reconfigure British society in a multicultural way, in effect a redistribution of power, whereas on the contrary we witnessed hegemonic containment, or what Sarat Maharaj described as ‘multicultural managerialism’. Araeen’s dilemma was that the demand for inclusion in any habitus – inscribed, according to Bourdieu, with largely unconscious codes – is a double-edged sword. As Derrida points out, inclusion implies accepting the authority of the ‘host’ and submission to the terms on which the host makes inclusion possible.30 To accept inclusion is to submit to a subtle form of subjection and control, terms that those artists who later rejected Britain were perhaps not prepared to tolerate: hospitality and hostility are two faces of the same coin. One could argue an ‘assimilationist’ tendency in the work of the ‘Commonwealth’ artists, consistent with the initial hopes and aspirations of the Windrush generation before disappointment and a sense of betrayal and isolation set in. With the exceptions of Souza and Locke, the art work was rarely overtly confrontational in content; but this may well be because this generation saw itself as belonging and contributing to what it anticipated as a non-partisan, international modernism underlined by universalist principles of a common humanity. By contrast, this somewhat utopian perspective could not be sustained by the 1980s post-conceptual, mostly British-born Black and Asian artists politicised by a social milieu fraught with prejudice, discrimination and racial tension. Eddie Chambers’s set of images Destruction of the National Front 1979–80 – in which the Union Jack, overlaid by blocks of red and black in an uncomfortable resonance of a swastika, is progressively shredded – became emblematic of the rejection of the presumed political ‘neutrality’ and ‘universalism’ of international modernism and its failure from the particularised perspective of the Black subject (fig.3). The demand of this generation was therefore not assimilation but overhaul of the art establishment itself.

Fig.3

Eddie Chambers

Destruction of the National Front 1979–80

Collage, four panels, each 35 x 20 cm

© Eddie Chambers

In retrospect, The Other Story was less a demand for inclusion as such than an exposure of the inherent lack in an institutional structure whose very coherence depended on exclusionary practices. Hence, if there was a demand it was for democratic institutions to fulfil their universalist obligations of extending socio-political and aesthetic agency to its entire citizenry; in other words, a demand for justice, appealing to the only court capable of dispensing it.

Nationalism, internationalism and cosmopolitanism

What Araeen called the ‘citadel of modernism’ emerges as a dreary British parochialism in which internationalism was too often led by the initiatives of non-British artists such as Denis Bowen’s New Vision Centre. Guy Brett’s frustration during this period with the lack of institutional recognition of the radical art practices of the 1960s and 1970s is palpable in his essay in The Other Story on internationalism. Much of this history remained outside the exhibition’s remit as it included a different constituency of artists, many of whom were temporary residents in exile from state violence at home and unaffiliated to British colonial geographies. I shall give only a brief summary in an effort to unravel a disjunction that some reviewers sensed in the exhibition. With hindsight this may be attributable to some fuzzy distinctions between exile and migration, internationalism and cosmopolitanism, the latter of which, I shall suggest, provides a partial conceptual link between the generation of ‘Commonwealth’ artists and the Black Arts Movement.

From The Other Story’s account of artistic and political radicality of the period I shall mention two figures, David Medalla (born 1942, Philippines) and Li Yuan Chia (born 1929 or 1932, China). Medalla remains an inveterate cosmopolite in the classical sense: Diogenes the exile, ‘citizen of the world’, refusing identification with any city-state. Amongst his many collaborative enterprises, Signals Gallery and Newsbulletin (1964–6) were instrumental in introducing to London audiences avant-garde Fluxus-like events, environments and installation from both Europe and Latin America at a time when the art establishment was so narrowly focused on the United States it also mostly ignored European art.31 Always engaged in collective interventions (contrary to the European concept of the autonomous genius), Medalla famously promoted art production as audience participation.32 Li Yuan Chia, now credited as the ‘father’ of Chinese abstraction, came via Italy to exhibit in Signals, and subsequently settled in Cumbria to create his own international gallery. Among the younger participants in The Other Story, Kumiko Shimizu, whose environmental work was displayed on the Hayward Gallery’s exterior walls, was an indirect heir to this historical strand.

Signals was forced to shut down following its critiques of the Vietnam War, but its participants were to return to political engagement in 1970 with the Artists’ Liberation Front, followed in 1974 with Artists For Democracy (AFD, 1974–7),33 dedicated to ‘giving material and cultural support to liberation movements worldwide’.34 However, if AFD was primarily focused on international politics, the emerging Black and Asian artists refocused attention on the socio-political crises at home.

In Paki Bastard-Portrait of the Artist as a Black Person, performed at AFD in 1977, and How Could One Make a Self-Portrait 1978, Araeen expressed the dilemma of the first generation diasporas, psychically caught between the place of departure as a lost belonging and a hostile place of arrival to which they could not fully belong. While much of the debate on displacement and exile was couched in terms of melancholy and loss, the literary critic and theorist Edward Said had a more nuanced approach.35 For Said, the postcolonial exile, who experiences two or more cultures, has another, cosmopolitan choice, which is potentially to ‘see the whole world as a foreign land’; that is, an original multi-dimensional – or ‘contrapuntal’ – vision, perhaps not essentially in conflict with Medalla’s assertion that any place he happened to be was ‘home’.36

I am not convinced, however, that the average ‘immigrant’ – who must reinvent belonging, with little expectation of return – has this freedom of detachment. In any case, the following generations were neither exiles nor immigrants but citizens under British rights of ius soli, and could not legally be subjected to those demands for ‘repatriation’ that Enoch Powell had notoriously levelled at their parents’ generation. In the soundtrack of a seminal work of 1983, Black Audio Film Collective’s slide-tape Signs of Empire, (not included in The Other Story), a politician announces that this indigenous diaspora generation ‘do not know who they are, or what they are.’ The comment was symptomatic of the establishment’s polarisation of ‘British’ and ‘black’, and inability to accept that the crisis of identity was more properly a post-imperial national one. The challenge to assumptions of national identity posed by Signs of Empire signalled a turn among younger artists towards more pluralised subjectivities, configured through a re-articulation of prevailing political realities with cultural counter-memories and neglected diaspora histories that extended beyond national boundaries. One might suggest, in the spirit of Said, that this generation of artists introduces a ‘postcolonial’ cosmopolitanism of multiple spatio-temporal attachments.

It is from this multiple perspective that The Other Story allows us to make a speculative connection between the trajectory of the Black Arts Movement and the earlier generation, drawing on the concept of cosmopolitanism Kobena Mercer introduces in Cosmopolitan Modernisms.37 In The Other Story chapter ‘Recovering Cultural Metaphors’, Araeen cites several of the earlier artists (Shemza, Egonu, Locke), who, to rebuild a sense of identity shattered by British indifference, reassessed their prior cultural heritage, producing in their work a ‘synthesis’ of diverse cultural experiences – a complex double articulation of modernism reflecting back on the sources that inspired it in the first place. ‘Synthesis’ specifies however a more fundamental condition that should not be understood on simply stylistic or iconographic grounds. As Said wrote, any artistic endeavour speaks from a place of beginning (a necessary fiction to be distinguished from the divine resonances of ‘origin’ that contaminate the entire history of modernist art criticism).38 It is therefore the bearer of both involuntary intangible culture (values, memories and philosophies) not necessarily bound to specific cultural signs, and voluntary identifications. The tyranny of exoticism or ethnocentrism is to insist that those who speak from a place of difference should also represent it in recognisable signs, as if this gave transparent access to the ‘other’s’ meaning: in effect, an already knowable unknown. Nonetheless, it is in the contradictions and aporias of cultural translation that a creative difference is produced. And by attending to this process we may eventually disclose what was so special about the ‘Commonwealth’ generation. In its own humanist, multiple spatio-temporalities, the work presents a vivacious amplification of modernism’s internationalism; one might describe it as Britain’s ‘lost’ cosmopolitan moment, commensurate with the aspirations of the Commonwealth federation, and prefiguring the ‘postcolonial’ cosmopolitanism of the Black Arts Movement.

Cosmopolitanism has re-entered the vocabulary in part to characterise global interdependency and in part to identify alternative pathways to the unpalatable choice between neo-liberal globalisation and ethno-nationalism. The new formulations of cosmopolitanism do not mean élite globetrotting flâneurs, belonging everywhere or nowhere, but globalism with responsibility. They counter the complacent metropolitan postmodern and globalisation myth that we are now liberated from belonging to anywhere in particular, but concede that we may have multiple belongings. Some versions, perhaps prematurely, speak in terms of a post-nation, global civil society and solidarity, which seems unrealistic whilst human identity remains a construction of particularised cultural memories. Others see cosmopolitanism as a social practice rooted in the particular but responsive to shared global realities, irrespective of nationalist agendas – i.e. not an ascetic detachment, but reattachment, or multiple attachment. Kwame Anthony Appiah defines it as a universalising of shared human values, needs and security, but not an homogenisation of ways of life (which is among the demands of neo-liberal democracy).39

Ulrich Beck insists that ‘internationalism’ and ‘cosmopolitanism’ are not interchangeable terms: ‘[In the cosmopolitan] the “either inside or outside” that underlies the distinction between the national and the international is transcended by a “both inside and outside”. The cosmopolitan outlook determines multiple spatial, temporal and practical both/and realities to which the national perspective remains blind.’40 It may be difficult to apply such neat distinctions to artistic diversity, except to suggest an emphasis on the ‘outside’ by the international avant-garde with its ambivalent attachment to formal genealogies and the (relative) autonomy of art, in contrast to the critical cosmopolitanism Mercer attributes to ‘other’ modernisms, whose aesthetics are grounded in an emancipatory politics of ‘both inside and outside’ and the multiple, transcultural spatio-temporalities of which Beck speaks. This genuinely transgressive as distinct from progressive modernism perhaps throws light on why avant-garde ‘internationalism’ has a rather uneasy presence in The Other Story.

Beck’s national ‘blindness’ evokes the institutional lack I spoke of earlier, but is too polite a description of British racially inscribed chauvinism, which, like the repressed, returned to haunt the 1990s and early 2000s. Despite international acclaim, in less than ten years the momentum gained by The Other Story and Black Arts Movement was submerged by the so-called Young British Artists (yBa), who were supported by an influential network that included Saatchi, White Cube, the Royal Academy, the British Council, New Labour and Tate Modern. One may speculate that the nationalist ‘Cool Britannia’ rhetoric that accompanied the institutional promotion of the yBas was symptomatic of a backlash against the politically inflected cosmopolitanism of the diasporas and an attempt to reassert an apolitical, if not overtly ‘white’ ‘British’ genealogy, in which the ultra-British postures of Gilbert & George were cited as precedents alongside a specious valorisation of (white) working-class culture.41

What constitutes ‘Britishness’ remains an obsession with political conservatism; but whatever it is, it now has to be configured with the multiple geographies of cosmopolitanism. The truth is that in multi-ethnic, multi-faith societies with trans-national affiliations, the nation state can no longer sustain its myth of unified spatio-temporality, and national identity is not, nor ever has been, co-terminous with cultural identity. As Tariq Madood has said, a multicultural society cannot be stable without developing a common sense of belonging among all its citizens, based not on ethnicity but on the political reciprocity between state and citizen.42 Only this can be the foundation of a just society and its institutions.

In summary, what The Other Story and its aftermath exposed is a philistine, British institutional parochialism concurrent with an experimental artistic cosmopolitanism that is never fully recognised or realised. Whilst one can argue that ‘cultural diversity’ has been institutionalised with respect to the circulation of contemporary Black and Asian artists,43 can the same be said for national collections and the higher levels of arts management? In a corrective riposte in the Evening Standard to Sewell’s assertion that, contrary to Araeen’s claim, the artists of The Other Story were neither ignored nor invisible, Sandy Nairne, then Director of Visual Arts at the Arts Council of Great Britain, listed only two artists represented in Tate’s Collection, whilst in the field of arts management there was but one Black or Asian officer among the entire national visual arts funding bodies.44 Twenty years on, is the story any different? Has justice finally been served?45