Fig.1

Thomas Gainsborough

Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape c.1750

Oil paint on canvas

765 x 642 mm

Tate T06746 / Gainsborough’s House

Photo © Tate

In Peter Darnell Muilman and Charles Crokatt, Thomas Gainsborough was presented with two young sitters born to commercial wealth at a time when both men were embarking on their own mercantile careers. Close in age, education and refinement around the time that Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape was painted in the early 1750s (Tate T06746; fig.1), Muilman and Crokatt were also connected by marriage. Art historian Hugh Belsey has plausibly suggested that the portrait’s third figure, the flute-playing William Keable, was included in the painting as the music tutor of one or both of these young men.1 Certainly, this and the provenance of the painting make it likely that the painting was commissioned by either the Muilmans or the Crokatts, although it is unclear which, as will be discussed below. This being the case, the work can be understood to capture not only a significant moment in Gainsborough’s development as a landscape and portrait artist, but the moment of elevation of two scions of London’s burgeoning overseas trade into the commercial and landed elite.

Born in Charles Town (now Charleston), South Carolina, in June 1730, Charles Crokatt was the eldest of James Crokatt and Esther Gaillard’s six children, five of whom would reach adulthood.2 Scottish-born James Crokatt had, after emigrating to Charles Town – South Carolina’s largest settlement and one of the most significant ports in Britain’s North American colonies – become one of the port’s leading merchants. Like many of his contemporaries, after establishing himself in transatlantic commerce in South Carolina, gaining valuable experience and building a network of clients and partners, James Crokatt relocated to London. In 1739 he established his trading house as the most important in London in the ‘Carolina trade’, exporting British and European manufactured goods and textiles to South Carolina and importing rice, indigo and naval stores from the colony.3

Peter Muilman was also born in 1730, to Henry Muilman, a London merchant of overseas origins and great commercial standing.4 Henry Muilman had come to London from Amsterdam in 1715 to establish a branch of the family’s trading house – the second largest in Amsterdam – in the British capital. Joined in partnership in the City of London by his brother, he left three other brothers in the Netherlands, and became a naturalised British subject in 1721.5 Achieving distinction in London’s trade with northern Europe, Henry Muilman was the first naturalised subject to become a member of the Russia Company’s Court of Assistants, was a director of the South Sea Company, and would serve as Danish consul in London.6

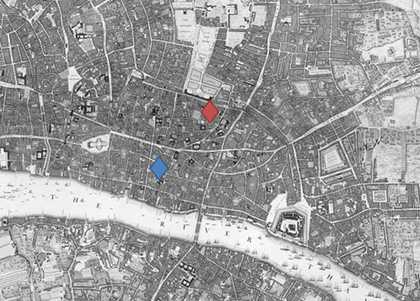

Fig.2

John Roque’s 1746 map of London, with James Crokatt’s premises marked in blue and Henry Muilman’s premises marked in red

Locating London’s Past, www.locatinglondon.org

As was customary among London’s eighteenth-century merchant community, both Charles Crokatt and Peter Muilman probably lived with their parents in residential quarters above their fathers’ trading premises in the City – in Crokatt’s case on Coleman Street and then Cloak Lane, off Cannon Street, and in Muilman’s on Winchester Street, close to London’s Dutch church at Austin Friars (see fig.2).7 By the time of their sons’ portrayal alongside Keable in Gainsborough’s painting, both James Crokatt and Henry Muilman had amassed commercial wealth on such a scale as to allow them to buy large country estates in Essex and entry into the landed elite.8 Crokatt bought Luxborough Hall, a grand country estate near Chigwell in Essex, in c.1749–50, spending an enormous £19,500 on acquiring the estate and an additional £10,000 on repairing and furnishing the property (see the engraving by John Walker after Conrad Martin Metz, East Front of Luxborough House, in Essex, the Seat of Sir Edward Hughes, Bart. 1788; fig.3). Besides the classical mansion itself and its eighteen acres of garden and forty-three acres of pasture, the Luxborough estate included the freehold in six farms covering 520 acres, with an estimated annual rental income of £575. ‘I think he has Grandeur enough for his Money’, reported Peter Manigault, a young Carolinian visitor to the estate in late 1750. ‘Mrs. Crokatt seems very much pleased with her fine House’, he added.9 At the same time, Henry Muilman bought Dagnams, a large estate near Romford in Essex. Within easy reach of London, both Luxborough and Dagnams allowed their owners – like the many other City merchants who acquired country properties on the capital’s fringes – the trappings of landed gentility while keeping up their business in the capital.10 Moreover, the two families were soon to become more than neighbours: they were to be in-laws.

Fig.3

John Walker after Conrad Martin Metz

East Front of Luxborough House, in Essex, the Seat of Sir Edward Hughes, Bart. 1788

British Museum, London

Manigault reported in February 1751 that the marriage between Charles Crokatt – ‘a very pretty young fellow’ – and Anna Muilman, in his words ‘the only daughter of a rich Hamburgh Merchant [Henry Muilman]’, was being planned. This may have been a deliberate strategy to consolidate the two families’ commercial success: the union was, according to Manigault, to be further cemented by the marriage of Anna’s brother, Peter Muilman, to Charles Crokatt’s younger sister, Mary.11 Manigault was less impressed by Peter Muilman than by Charles Crokatt, however, writing to his mother that ‘young Muilman by what I have seen, and heard of him, is not quite so agreeable as could be wished’.12

It was in this context of strengthening bonds between the Crokatts and Muilmans that Gainsborough was commissioned to paint the two eldest sons of each family. Whether the painting was commissioned by Charles Crokatt or by Peter Muilman, or indeed by one of their relations, is impossible to resolve definitively. The union between the Crokatts and Muilmans and their newfound status as country landowners would certainly have been worthy of commemoration by either family. The fact that the picture was passed down through Anna Muilman’s line leaves open the possibility that the picture was intended for her, as the sister and wife of the two principal sitters.13 A precise identification of the figures is similarly elusive. A label formerly attached to the back of the painting identifies each of the three sitters, although only the central figure playing the flute can be securely identified as Keable. As such, while the two remaining, better-dressed figures certainly depict Muilman and Crokatt, it is not known which of these young men is the second seated figure on the left and which the one standing on the right.

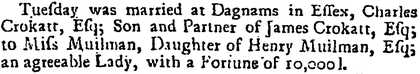

Captured in Gainsborough’s portrait at the apex of their fathers’ elevation into the landed country elite and of their own emergence as young men of refinement and promise, neither Charles Crokatt nor Peter Muilman would repeat their fathers’ commercial successes. The complexities of Crokatt’s later life were prefigured in the story of his marriage to Anna Muilman.14 Rather than a conventional marriage at either Crokatt’s or Muilman’s parish church in the City of London, their wedding took place at St George’s Chapel, Mayfair, in April 1752. The chapel, not to be confused with the more refined premises of nearby St George’s, Hanover Square, was a venue notorious for performing so-called ‘clandestine marriages’ – ceremonies that were valid and binding in law, but for which no licence had been obtained, no banns read and, often, no parental consent given. Charles and Anna Crokatt’s wedding was one of 146 to take place at the chapel in April 1752 alone.15 Why the wedding took place at St George’s is unclear. By all appearances the union had the blessing of both families: bride and groom were socially compatible and Anna Muilman brought with her a dowry of some £10,000.16 Adding to the mystery, a contemporary newspaper report in the London Evening Post stated that the marriage took place in September 1752 at Dagnams, Henry Muilman’s country manor in Essex (fig.4).17 Why such apparent subterfuge? Perhaps these circumstances point to the most common reason for such ‘clandestine’ unions – that it was done in haste because of pregnancy. Or perhaps, the gossip of Manigault and the like notwithstanding, one or other of these families had hopes for a superior social match for their child.

Fig.4

Newspaper article reporting the marriage of Charles Crokatt to Anna Muilman

London Evening Post, no.3881, 1–14 September 1752, p.1

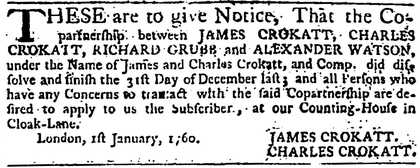

Whatever the exact circumstances of the union between Charles Crokatt and Anna Muilman, the mooted marriage between Peter Muilman and Mary Crokatt never took place.18 Peter Muilman joined his father in partnership in his London trading house which, like most mercantile contemporaries, was maintained even after buying a large country estate. He died, apparently unmarried and without children, in 1766.19 Charles Crokatt’s life after his marriage to Anna Muilman can be more completely reconstructed. He formally entered partnership with his father in 1754, receiving £4,000 from him to allow him to take a 20 per cent stake in the business, renamed James and Charles Crokatt & Co. The partnership continued until the arrangement, which also included partners Richard Grubb and Alexander Watson, broke down acrimoniously in 1759 and was dissolved in early 1760 (fig.5).

Fig.5

Notice reporting the dissolving of James and Charles Crokatt & Co

Public Advertiser, no.7829, 2 January 1760, p.1

James Crokatt later alleged that he had had ‘many proofs of the Negligence and Misconduct’ of his three minority partners, including Charles, and he would find on liquidating the accounts of the dissolved partnership that his son had ‘taken very considerable sums of Money’ from the firm without his knowledge.20 After a further ten years of financial misconduct that led to mounting debts, and facing bankruptcy, Charles Crokatt committed suicide in April 1769.21 He was survived by four children and his wife, Anna, who married the London merchant John Julius Angerstein in 1771.22 It was down this line of the family that the portrait was passed until it was jointly bought by Gainsborough’s House and Tate in 1993.

Commissioned to represent Peter Muilman and Charles Crokatt at the moment of their commercial and social ascendance, Gainsborough’s painting instead captures more fully the wealth and elevation of the previous generation. Henry Muilman and James Crokatt were immigrant merchants who had capitalised upon the great profits to be made in Britain’s overseas trade in the mid-eighteenth century, spending their proceeds on landed estates and stylish luxuries such as music tuition and fashionable clothes for their offspring. Not least among these fine acquisitions was a painting by Gainsborough. In celebrating the refinements of a new generation, the commission was a resounding statement of the confidence of these prosperous mercantile dynasties even if it did not, in the event, prove a harbinger of their continuing success.