Fig.1

Thomas Gainsborough

Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape c.1750

Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape c.1750 (Tate T06746; fig.1) belongs to an eighteenth-century sub-genre of portraiture known as the ‘conversation piece’. Such pictures are distinguishable from more formal categories of portrait by the small-scale presentation of their sitters in sociable little gatherings. In such images, both mixed and single-sex sitter groups are common, typically connected to one another by friendship, family, or a combination of the two. As historian Huw David observes elsewhere in this publication, since the exact date of Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape is unknown we cannot be certain whether the piece was commissioned as a celebration of friendship or the union of two families through marriage. (Charles Crokatt married Peter Muilman’s sister in 1752.)1 ‘Conversation’ was closer in usage to the modern term ‘interaction’ in the eighteenth century, so refined activities like tea-drinking and card-playing provided the scenarios for these group portraits as often as congenial discourse. Depending on the taste of the patron or the occasion being marked, other pastimes popular for enactment included reading aloud, toying with pets or, as in this example, taking the air and making music. Having leapt into fashion in the 1730s, conversation pieces remained in demand well into later decades of the century, keeping a number of specialists in the field, like Thomas Gainsborough in the 1740s and 1750s, in good business at any given time.2

The popularity of this form of portraiture derived in large part from its peculiar effectiveness in conveying the prized quality of politeness in its sitters.3 The pervasiveness of this term in eighteenth-century Britain went hand-in-hand with broader shifts in the behaviour and constitution of the period’s social elites. In ways that seem to have appealed equally to large swathes of the traditional landowning classes and the ever-growing ranks of those such as the Muilmans and Crokatts who had earned their fortunes through trade and in the professions, the urbane culture of politeness scorned both vulgarity and pomposity in social intercourse, just as it disavowed both meanness and ostentation in consumption. Outwardly manifest in refined but affable manners and in the cultivation of good taste, politeness for its most serious advocates also betokened a deeper probity, and even virtuousness, that counteracted the rampant selfishness and materialism threatened by an increasingly commercial society. What the conversation piece offered to mercantile and aristocratic elites alike was a decorative rehearsal of those social situations – a music party, a country walk – that best demonstrated not only the personal refinement of wealthy individuals of different stripes, but the harmonious relations that mutual civility and shared tastes fostered between them.

Fig.2

Philippe Mercier

The Music Party 1733

National Portrait Gallery, London

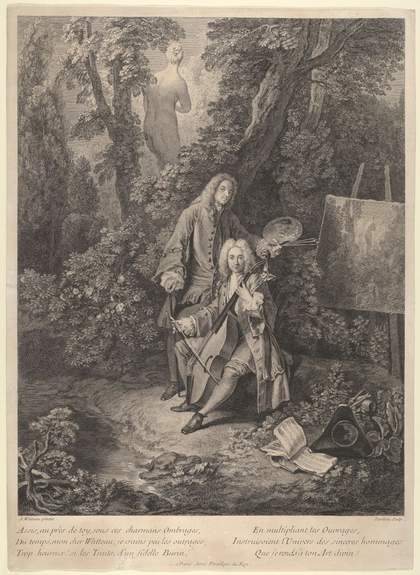

By the time Gainsborough turned his hand to the depiction of Muilman, Crokatt and Keable, the idea of a conversation piece that celebrated simultaneously the sociable delights of landscape and music-making had acquired a cosmopolitan pedigree that itself signalled distinction and refinement. An important precedent along these lines had been commissioned around two decades earlier by no lesser figure than Frederick, Prince of Wales, from the Huguenot painter Philippe Mercier: The Music Party 1733 (fig.2), which depicts Frederick and his sisters. Innovative at the time in its informality – especially for a royal likeness – the painting depicts the prince in one of the family’s pleasure parks playing intently on the bass-viol.4 Absorbed in their shared artistry, two of his sisters accompany him on a mandora and a harpsichord while a third gazes out at the viewer with a volume of poetry open on her lap. Mercier’s French origins were significant. For just as the gloss of courtly politesse was a vital ingredient of British polite conduct, the elegant art of modern France was a rich source of models for conversation pieces – not least the fête galante compositions of Antoine Watteau, whose original pictures found a ready market in early eighteenth-century England, and inspired a raft of imitations and printed reproductions.5 Indeed, it is probably no coincidence that in several important respects, Gainsborough’s Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape more closely resembles the better-known portrait of Watteau and his patron, Jean de Julienne, than the Mercier (see Nicolas-Henri Tardieu’s 1731 etching with engraving after the original; fig.3).6 Here, the pleasures of landscape figure doubly, in the form of the fête galante at which the painter works and in the dappled forest clearing he occupies with his companion. At the same time, Jean de Julienne plays his viol da gamba and smiles at the viewer, as if to lend an air of financial disinterestedness to his friend’s art and an aspect of serious endeavour to his own.

Fig.3

Nicolas-Henri Tardieu ?after Antoine Watteau

Assis, au près de toi… 1731

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

As in Watteau’s portrait, musical and country pleasures in Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape are seen to overcome the significant class difference between its sitters, producing an image of harmonious masculine friendship. Muilman and Crokatt, the two outer figures, were the eldest sons of two of the City of London’s most successful overseas traders, at that time in the midst of acquiring the expensive trappings of the landed gentry.7 (It is not known which of these sitters is Muilman and which Crokatt.) On the other hand, the central figure on the fashionable transverse flute, William Keable, was a minor painter whose limited professional success lay before him, as detailed in musicologist and baroque flautist Hannah French’s and art historian Peter Moore’s essays in this publication.8 The impression of intimacy and familiarity between these widely differing individuals is created not by animated interaction – all of the figures gaze out at the viewer – but by a suspension of the action of a pleasant walk for a spontaneous moment of musicality.

Crucial to the picture’s impression of poised togetherness is the sensitive disposition of the figures and, even more crucially, the delicate relationship the composition establishes between them. The multiple tweaks and adjustment to the figures revealed by Rebecca Hellen and Alexandra Gent’s detailed conservation analysis of the picture’s creation show this to have been a high priority in the commission.9 While the ceremonious courtly pose of the standing figure on the right caused Gainsborough little trouble, major changes to the left-hand figure reveal that its more pleasing brand of elegant nonchalance – informally crossed legs, arms and spine in repose, a cocked hat – required rather more work to achieve. In fact, Lord Chesterfield’s contemporary letters to his illegitimate son, designed to guide him round the pitfalls of high society, make plain that the business of cutting a polite figure at this time was no less challenging in reality than it was in visual representation. ‘There is nothing more difficult to attain or so necessary to possess, as perfect good-breeding,’ he warned, ‘which is equally inconsistent with a stiff formality, an impertinent forwardness, and an awkward bashfulness.’10

Fig.4

Thomas Gainsborough

Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape, detail of the sitters

Photo © Tate

Looking at the grouping of these men in its entirety, the picture’s tactics for achieving an overall impression of informal coherence becomes apparent. Not least among these is the flowing recurrence of certain motifs (fig.4). Thus three pairs of white stockinged legs collapse and straighten into an attractive inverted arc across the bottom portion of the canvas. All the while, a serpentine pattern of hands, arms, walking canes and flute winds elegantly through the middle of the group. Colour also plays an important role in this respect. Echoing mid-eighteenth-century portraits of gentlemen in uniform hunt liveries,11 the way in which Muilman, Crokatt and Keable are each clothed a variation on red, grey and black works to unite the figures formally, giving outward form to a kind of collective social identity.

But if, in these ways, Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape politely plays down the difference in rank and circumstance between its sitters, it was not at all unusual as a conversation piece in also pointing discreetly to the significant social and economic imbalance within the group. That the true parity in this group of friends exists between the two wealthy young merchants who flank the figure of Keable is manifest in slight but unmistakable ways. Thus, all three men are fashionably attired, but only Muilman and Crokatt have an expensive trim to their coats. While Keable has embellished his hat with silver decoration, Muilman and Crokatt can afford gold. Muilman and Crokatt have powdered hairstyles, furthermore, while Keable’s remains its natural brown colour.

In fact, we know that the members of the overseas trading class to which Muilman and Crokatt belonged were particularly noted for the subtle but nonetheless evident ways in which they distinguished themselves from other members of urban society through their attire. With demonstrably substantial capital a prerequisite for the profession but prudence in money matters no less essential, as historian Perry Gauci has observed, ‘merchants prided themselves on an outward appearance of modest refinement’. Their most ‘prized personal items’ tended to include ‘gold watches, gold-topped walking canes, or gold rings denoting bonds of affection and connection’ which only ‘perceptive visitors [to the City] would have picked up on’.12

Even more telling of the real distribution of social status in the picture is the delegation of musicianship to Keable. The flute and carefully rendered embouchure of the lips partially obscure his likeness, strongly suggesting that the weight of importance in the commission was placed on the other two figures. Moreover, while every one of the sitters is elevated by this group demonstration of fine musical taste, the picture nonetheless divides its sitters into cultural providers on the one hand and consumers on the other.13

Fig.5

William Hogarth

The Strode Family c.1738

Tate N01153

Photo © Tate

Art historian Hugh Belsey has suggested that Keable is included in the portrait as the young men’s flute instructor as well as their friend.14 Although no other documentation has been found of this second string to this painter’s bow, the speculation is highly plausible, especially when a somewhat earlier, and in other respects rather different, conversation piece like William Hogarth’s The Strode Family c.1738 is taken into consideration (fig.5). Here the key point of comparison with the Gainsborough is the relationship Hogarth depicts between the two sitters at the far left-hand side of his composition. These figures are the commissioner of the portrait, the successful South Sea broker William Strode, enjoining his former tutor and Grand Tour guide, Dr Arthur Smyth, to put down his book and join his family at the tea table.15 In their different cultural spheres, Keable and Smyth are both evidently celebrated in these pictures for their personal value as well as the services they provide, yet typically of such groupings, their presence is ultimately required to demonstrate the elegant taste and high culture of the principal sitter (usually also the patron), and politely to gloss its commercial acquisition as a kind of sociable interaction.

Despite being painted when Gainsborough had moved back from London to his native Suffolk, Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape demonstrates his ability to fulfil commissions that fluently spoke the language of metropolitan politeness. Depicted at a pointed remove from the feverishly competitive sphere of urban commerce from which they continued to derive their wealth, the two principal figures of Muilman and Crokatt can be seen as a consummate embodiment of mid-eighteenth-century polite sociability and its refining influence. For while the setting of the conversation piece is one of rustic tranquillity, the fashionable dress and deportment of these gentleman as well as their taste for a distinctively modern musical instrument are emphatically urbane in flavour.16 Brought together in an intimate concert champêtre that itself bestows a cosmopolitan flair on this work of art, these men of trade and commerce are here presented, above all, as polished and amiable young gentlemen. The picture answers the call of good breeding for uncondescending interaction across the classes, but it also fulfils portraiture’s other duty to distinguish, however subtly, between the different social degrees of its sitters – and, in the process, the limits of polite equality.