Fig.1

Thomas Gainsborough

Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape c.1750

As its title suggests, landscape plays an important role in Thomas Gainsborough’s Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape c.1750 (Tate T06746; fig.1; hereafter Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape). The three modishly dressed sitters, comprising the scions of two of the City of London’s most important overseas trading families and the painter William Keable on the flute, are enveloped on all sides by a scene of remote, rustic tranquillity. This gentlemanly concert champêtre takes place atop a wooded hill while a long vista unfolds below, taking in a lone cottage, a sandy bank, a copse and – in the far distance – a church tower. Large cumulus clouds billow above the low horizon scattering patches of light and shade across the view.

The landscape also helps to organise and complement the composition. While the shadowy wood provides a dark screen to throw fine silks and rosy complexions into relief, the gently rising bank, with its tussocks and burdock leaves, forms a framework on which the figures are elegantly disposed. The central oak tree – so closely observed that it almost constitutes a fourth likeness – is crucial, joining the airy top left-hand corner of the picture to its earthbound bottom right and uniting the three men in a single unit.

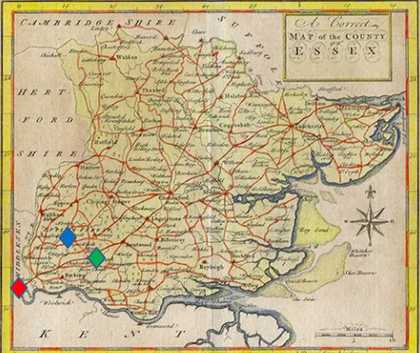

Fig.2

Thomas Osborne’s 1748/50 map of Essex, engraved by Thomas Hutchinson, with London marked in red, Luxborough marked in blue and Dagnams marked in green

Genmaps, http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~genmaps/

The significance of the landscape in this picture has been very plausibly attributed to the particular circumstances of the Muilman and Crokatt dynasties. As historian Huw David explains in detail,1 both of these families, who were united by the marriage of Charles Crokatt to Peter Muilman’s sister Anna in 1752, had recently bought extensive country estates in close proximity to one another in the county of Essex. By the time the portrait is thought to have been painted, the Crokatts had acquired Luxborough, near Chigwell, and the Muilmans had bought Dagnams, some six miles away, near Romford (for a map showing these locations, see fig.2).2 In an unpublished research document in the Gainsborough’s House archive, art historian and former director of the museum Hugh Belsey suggests that this rural portrait was prompted by just this ‘passing of the family’s status from commerce to landed gentry’.3 Art historian Peter Moore takes this idea further in his essay in this In Focus, pointing to a wider culture among the mercantile classes for acquiring the trappings of the propertied country gentleman.4 Read in this way, the landscape in this portrait becomes a potent symbol of gentility and an index of upward social mobility.

Convincing as this line of argument is, the present essay proposes that the carefully rendered landscape in this portrait served more than one purpose, and that it signified a cosmopolitan and even distinctly mercantile refinement in taste as much as it did a newly genteel landed status. Landscape, after all, had begun to emerge as an important artistic genre in its own right by this date in England, and a complex one at that, imbued with a range of significant meanings. A number of factors give initial pause for thought when approaching this dimension of Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape.

Fig.3

Thomas Gainsborough

Mr and Mrs Andrews c.1750

National Gallery, London

It is worth observing, for instance, that far more obvious depictions of the eighteenth-century country estate were available to the patrons of Gainsborough’s outdoor conversation pieces.5 Robert and Frances Andrews, for example, had themselves depicted in a more or less literal portrayal of the Auberies, their Suffolk estate just outside the artist’s hometown of Sudbury (see Mr and Mrs Andrews c.1750; fig.3). This portrait is likely to have been commissioned to celebrate the union of two adjacent properties which the couple’s marriage achieved, and which is paraded here as a model of up-to-date land management.6 More popular among Gainsborough’s sitters were ornamental parkland surroundings that evoked the idea of landed gentility no less ambiguously, if in a rather more metaphorical fashion. Thus the parents of Frances Andrews, who like the Muilmans and Crokatts were commercial people with bases in both the City of London and East Anglia,7 opted to present themselves within a silvery grove before a large piece of classical stone garden statuary in Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Carter c.1747–8 (fig.4).8

Fig.4

Thomas Gainsborough

Mr and Mrs Carter c.1747–8

Tate T12609

Photo © Tate

By contrast, Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape belongs to a third type of Gainsborough conversation piece, set instead within scenery more evocative of ‘common land’.9 That is to say, a communally managed terrain of rutted roads, open pasture, small woods and modest cottages, to which, in contrast to a private pleasure garden or an ‘enclosed’ landscape like the Andrews’s, the poor of the parish had customary rights to forage. As art historian Mark Hallett has demonstrated, such tracts of open countryside were also becoming popular sites for the leisured (although not necessarily landed) members of society to roam, to take the air and generally to enjoy the view.10 Muilman, Crokatt and Keable are depicted, in other words, within a landscape in which the polite classes were taking increasing pleasure, yet not in a fashion that was inevitably or implicitly proprietorial.

Fig.5

Thomas Gainsborough

Sarah Kirby (née Bull); (John) Joshua Kirby c.1751–2

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Gainsborough also depicted his great friend, the artist and antiquarian Joshua Kirby, in just this kind of rough-and-ready setting alongside his wife, Sarah, and their dog (Sarah Kirby (née Bull); (John) Joshua Kirby c.1751–2; fig.5).11 Yet the obvious disparity in the levels of finish and detail between the countryside scenery in this picture and the one included in Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape gives an additional prompt to think a little more about the problematic status of the landscape element in the latter. As conservators Rebecca Hellen and Alexandra Gent make clear,12 the nuance and complexity of the landscape in this portrait are exceptional in the corpus of Gainsborough’s early portraits even when differences in the condition of the works are taken into account. Indeed, it is more on a par with the ‘standalone’ rustic landscapes in the seventeenth-century Dutch manner for which Gainsborough was far better known at this stage, at least in the fashionable London art world. For these reasons, I propose that we ought to consider the landscape of Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape, especially the vista that opens out on the left-hand side of the canvas, in more than one way; not only as a generalised ‘natural’ backdrop to consolidate the newly landed identity of its two mercantile sitters, but also as a kind of painting within a painting, designed to show off their taste in the artifice of a reputed landscape specialist.

Fig.6

Francis Hayman

George Dance the Elder c.1750

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

In this respect, the picture may be said to have less in common with Mr and Mrs Andrews than it does with Francis Hayman’s contemporary portrait of the City of London surveyor George Dance the Elder, in which the sitter proudly presents himself next to a gold-framed rustic landscape (George Dance the Elder c.1750; fig.6). Indeed, with its irregular groves, billowing clouds and distant spire, the landscape displayed on Dance’s wall is remarkably similar to the one behind Gainsborough’s sitters in a comparable place in the composition.13 I want to suggest that in Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape no less than in George Dance the Elder, landscape as art and as a locus for the performance of modern connoisseurship has a prominent role to play in the self-presentation of significant City figures. (It is worth noting, furthermore, that Gainsborough painted at least one landscape background for a Hayman conversation piece around this time, not as a piece of hackwork but as a signature addition by a named artist, of which its metropolitan patron could proudly boast.)14

There is a distinct possibility, in fact, that Gainsborough was better known to the Crokatts and Muilmans as a landscape painter than he was as a portraitist, and that his abilities as such were an unusually important dimension of the commission. In London, where these families were primarily based, Gainsborough had built up an impressive reputation as the leading specialist in rustic landscape art, which he worked hard to sustain even after his move to Suffolk. Throughout this period he produced landscape designs for publication in the capital, and also supplied speculative works for sale through the Soho art dealer Panton Betew.15 Indeed, the earliest known patrons of this phase of Gainsborough’s landscape production were all London residents.16 By the same token, the southernmost part of Essex occupied by Luxborough and Dagnams was far removed from those Suffolk circles of patronage that generated most of Gainsborough’s other conversation pieces (fig.2).

Fig.7

Thomas Gainsborough

The Charterhouse 1748

Foundling Museum, London

Yet perhaps the most compelling reason of all to emphasise Gainsborough’s superior reputation as a landscapist in relation to the commission of Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape is the fact that, in 1750, James Crokatt, father of Charles, was elected a governor of the Foundling Hospital in London.17 It was to this institution that Gainsborough had recently donated a landscape roundel of the Charterhouse School to hang alongside works by the established masters in the field, where it was nevertheless ‘tho’t the best & masterly in manner’ (The Charterhouse 1748; fig.7).18

But if these circumstances imply that Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape was first regarded as a portrait and a landscape as well as a portrait in a landscape, what particular kind of connoisseurship could such a commission advertise? Indeed, what might have been at stake for these sitters in being so closely associated with a painted view by this precocious master? To begin to answer these questions, we must first consider the particular esteem in which Gainsborough’s landscape art was held at mid-century.

Fig.8

Thomas Gainsborough

Landscape after ‘La Forêt’ by Jacob van Ruisdael 1746–7

Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester

Fig.9

Thomas Gainsborough

Cornard Wood, near Sudbury, Suffolk 1748

National Gallery, London

The extremely close resemblance of Gainsborough’s early rustic landscapes to those of earlier Dutch masters, notably Jan Wijnants and Jacob van Ruisdael, has been noted with approval since the eighteenth century.19 In more recent accounts, art historians have looked beyond this typical formulation of artistic influence and pointed out that Gainsborough began producing these works on the crest of a wave of popularity for the Dutch originals in the London old master market of the 1740s. The taste for such paintings, which epitomised the preference for brilliantly painted yet intellectually undemanding ‘cabinet’ pictures, was led by an aristocratic elite of collectors.20 In an art market largely driven by emulative consumption, curator Susan Foister observes, Gainsborough was just one prominent figure among a number of British artists who ‘were inevitably attracted … to make imitations and, in some instances, forgeries’ of these modish commodities.21 In fact, we know just how closely Gainsborough looked at Dutch landscapes to cater for this market from a precise chalk study he made after a Ruisdael (Landscape after ‘La Forêt’ by Jacob van Ruisdael 1746–7; fig.8), which he then elaborated upon to create Cornard Wood, near Sudbury, Suffolk 1748 (fig.9).

Fig.10

Jacob van Ruisdael

Peasant Cottages in Dunes 1647

State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

The landscape that envelops the figures of Muilman, Crokatt and Keable is a medley of immediately recognisable (perhaps even deliberately clichéd) elements from the Dutch tradition. Here, of course, is the ‘introduction’ of a Wijnants-like burdock plant, which fills the prominent space at the bottom of the picture below the figure of Keable. Even more tellingly, in the middle distance of the ‘standalone’ vista, the triple composition of the tumbledown cottage, the sandy hillock and the little oak copse repeats one of the most frequently recurring tropes in all Dutch landscape art. Indeed, it is as if a classic Ruisdael, such as Peasant Cottages in Dunes 1647, has been shrunk down and carefully inserted into the left-hand side of the canvas, so perfectly does it imitate the manner and format of that artist (figs.10 and 11). For here is not only a characteristic Ruisdael subject,22 but a convincing imitation of his admired grainy yet delicate application, of his use of a low, lopsided horizon line and of his dramatic way of throwing a band of golden light across shaded terrain, often picking up, as he does here, the exposed flank of an inland sand dune.23

Fig.11

Thomas Gainsborough

Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape, detail of the landscape

Photo © Tate

During the throes of his final illness in 1788, Gainsborough would come to look back with nostalgia upon his earliest landscape style, noting that ‘tis odd how all the Childish passions hang about one in sickness, I feel such a fondness for my first imatations [sic] of little Dutch Landskips’.24 It is important to dwell for a moment on the nuance of this utterance. In eighteenth-century cultural discourse, the term ‘imitation’ did not have the connotations it now has of an affordable but inferior approximation, but referred instead to a rather more creative kind of response that combined something of the originator and of the imitator, and something of the past and of the present. In the art world, the more specific term for this kind of creative imitation was ‘pastiche’ (a term which, likewise, has been degraded over time). The discussion of this kind of picture in the 1750 translation of Roger de Piles’s The Art of Painting provides an especially useful and detailed insight into how a cleverly Ruisdael-like but, on closer inspection, evidently modern Gainsborough might have been enjoyed:

It remains for me to say something of those pictures that are neither originals nor copies, which the Italians call pastici … A Painter that would deceive in this way, ought to have, in his mind, the manner and principles of the master of whom he would give an Idea, whether he takes any part of a picture which that master has made and puts it in his own work, or whether the invention is his own, and imitates lightly, not only his touches, but even his goût of design and colouring. … There are some … pastici made with so much cunning, that the eyes of the most judicious are surprized by them at first sight; but soon distinguish the one’s colouring, and the one’s pencil [i.e. brushwork], from the other’s.25

This quotation provides a sense of the light touch and ingenuity that such pastiches required of their makers, but also the pleasant surprise which they gave to their viewers, as the work of a famous master dissolved under their ‘judicious’ gaze and was reconfigured as a work of modern ‘cunning’. De Piles makes it clear that no permanent deception was intended by the production of these ‘counterfeits’, for the principal part of the diversion lay in its revelation. The emphasis is on fun and game-playing; indeed, on a kind of pleasant sociability between the artist, object and patron.26

Of course, the sitters and patrons of Gainsborough’s conversation piece could never have intended to mistake any part of their commission for a much older work by another hand, yet the inclusion of this little Ruisdael pastiche could nonetheless deliver much of the punch of this highly sophisticated form of art. Here, it can be proposed, was a picture within a picture that cleverly asserted itself neither as an original nor a copy and that, in reversing the typical process of a pastiche, slowly revealed an old master’s ‘touches [and] even his goût of design and colouring’ within an otherwise ostensibly modern work of art.

But besides pointing out the distinction that so close an association with the simultaneous social and aesthetic delights of pastiche could bestow, can we conclude by being any more specific about the significance of all of this to these particular sitters? Perhaps the cosmopolitanism of pastiche, and of the exceptionally international milieu in which overseas traders lived and worked, provides one answer. As musicologist and baroque flautist Hannah French demonstrates, the flute-playing featured prominently in this picture was replete with sophisticated European associations.27 This is no less true of mid-eighteenth-century English landscape production which, as this essay has argued, can be understood in relation to the Franco-Italian pastiche tradition here applied to fashionable Netherlandish models. Successful City merchants, meanwhile, were no less cosmopolitan in outlook than their aristocratic counterparts with their Grand Tours and diplomatic postings,28 although this personal quality was put to quite different purposes. Besides substantial capital, a demonstrable competence in the manners and customs of overseas cultures was one of the most important ways in which great family operations like the Dutch Muilmans and transatlantic Crokatts gathered backing for their projects.29 Indeed, having been schooled in business in a London headquarters, up-and-coming members of trading families were habitually sent to foreign outposts to ‘learn the fine details of their trade at first hand, and make contacts that could have a crucial long-term influence on their businesses’.30

But there was also a cultural and social dimension to this cosmopolitanism. As historian Perry Gauci observes, ‘eighteenth-century commentators were increasingly prepared to accord [overseas] merchants a distinctive role at the apex of economic life, and their cosmopolitanism only served to differentiate them from the rest of the commercial world.’31 One of the most frequently noted ways this manifested itself was in the highly praised fluency in multiple modern languages. But in a milieu in which cosmopolitan self-presentation returned both commercial and social dividends, an internationally flavoured commission like Muilman, Keable and Crokatt in a Landscape must surely have made a valuable contribution. Painted for a pair of families that continued to trade internationally in the City even as they assumed their place in the country squirearchy, the singular complexity of the landscape in this conversation piece may well derive from a paradoxical double life; as a scene, at once, of natural English retirement and of urbane cosmopolitanism of the utmost contrivance.