Fig.1

Thomas Gainsborough

Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape c.1750

The prominent inclusion of a transverse flute in Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape (Tate T06746; fig.1) reflects the great popularity of this musical instrument among English gentlemen of the mid-eighteenth century.1 Having been introduced from the Continent during the post-Restoration surge in music-making of all kinds, this distinctly modern and fashionable instrument had since flourished in the market-led musical life of the nation, and was patronised across the polite classes.2

By this period, makers such as Pierre Jaillard Bressan, Thomas Cahusac and Thomas Stansby Jr had honed the construction of the flute,3 professional performers such as John Loeillet had grown ever more specialised, and composers had long since been fuelling the public appetite for virtuosic solo pieces and concertos.4 Thanks to the printing of scores by London’s numerous music publishers (notably John Walsh the Elder) and the movement of skilled instructors,5 amateur flute-playing had spread rapidly from the capital to provincial centres. Regarded as an artistic development of the recorder and capable of nuanced playing in articulation, dynamics and tone, by the 1750s the instrument was firmly entrenched as an indication of refinement in good taste and an apt pastime for the English aristocracy and aspiring classes alike.6

William Keable, the figure playing the flute in Gainsborough’s portrait, was a prime example of this kind of upwardly mobile enthusiast. The key known facts of his life and career are discussed in Peter Moore’s essay in this publication, however his musical life becomes significant in the 1740s, a time in which he was a London-based painter who could enjoy and find inspiration in the virtuosic flute obbligato arias at the city’s opera house.7 Subsequently based in Norwich, he would have had little trouble accessing the flute repertoire published specifically for amateur players. Lists of subscribers published in each new collection of this kind reveal a veritable who’s who of London’s musical movers and shakers, but also document the patronage of musical societies and more modest individuals at some remove from the capital. As a Norwich resident, Keable may have laid his hands on Michael Festing’s Twelve Sonatas in Three Parts (1731), which lists that city’s Musical Society among its many subscribers. Indeed, Norwich was a particularly active centre of amateur music-making and was renowned at the time for the quality of performances.8 Since 1724 there had been a regular ‘Musik Meeting’ to which ‘any Gentlemen that are Lovers of Harmony’ were invited to be admitted into the ‘Musical and Friendly Society… either as Members, or Clubbers’.9 As an amateur violist and member of the Ipswich Musical Society, Gainsborough himself was also involved in such regional musical activities.10

Fig.2

Thomas Gainsborough

William Woolaston c.1759

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service, Colchester and Ipswich

Fig.3

André Bouys

La Barre and other Musicians c.1710

National Gallery, London

Fig.4

Antoine Watteau

L’Accord Parfait 1719

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

The specific reference to the ‘gentlemen’ amateurs of Norwich in particular is significant in relation to the flute, which was deemed ‘improper’ for ladies, ‘as taking away too much of the Juices, which are otherwise more necessarily employ’d, to promote the Appetite, and assist Digestion’.11 The instrument seems to have been particularly linked to elite male pastimes, with no less visible a proponent than Frederick the Great of Prussia.12 The inclusion of Keable with the instrument in Gainsborough’s portrayal is nonetheless somewhat unusual. Cultural historian Richard Leppert has suggested that the relative paucity of flautists in portraiture points to a conflict over ‘the competing interests of men who may have loved music sufficiently to have its trace included in their portraits, but who were nevertheless part of a culture which increasingly and systematically marked music as improper for a man’.13 When gentlemen did choose to be painted with a flute, they typically avoided being shown ‘in action’.14 For example, Gainsborough’s somewhat later portrait of another flautist, William Wollaston, shows him posing with the instrument resting against his middle (William Wollaston c.1759; fig.2). Various other resting poses can be seen in André Bouys’s earlier depiction of Michel de la Barre and other musicians of c.1710 (fig.3). However, perhaps because he is unlikely to have been Gainsborough’s patron for this portrait, Keable is portrayed mid-performance on his transverse flute, leading to the slight obscuring of his face and the distortion of the serene expression more typical of polite English portraiture of the period.15

The flute had deep cultural associations with the outdoors. Commonly linked with bucolic themes, it featured prominently in English pastoral compositions, such as Thomas Arne’s cantata ‘The Glorious Sun’ (1762) and Georg Frederick Handel in ‘Sweet Bird’ from L’allegro, il penseroso ed il moderato (1740) to name but two of the most celebrated examples.16 In the European landscape tradition, Arcadian figures playing woodwind instruments are similarly commonplace. Gainsborough’s portrait specifically draws on Antoine Watteau’s fête galante refinement of this theme, in which elegant and fanciful figures are frequently to be found playing modern transverse flute in outdoor gatherings, as is seen, for instance, in Watteau’s L’Accord Parfait 1719 (fig.4).

Fig.5

Thomas Gainsborough

Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape, detail of objects held by sitters

Photo © Tate

However, notwithstanding the fictive nature of this pictorial source (nor the acoustic impracticality of the early flute for effective outdoor performance) there appears to have been a strong link in actual practice between the seemingly disparate gentlemanly pursuits of country walking and flute playing. It is notable that all three figures in the Gainsborough portrait carry either a flute or a walking cane, and that the eye is drawn to the rhythmic arrangement of these objects at similar heights and angles across the canvas (fig.5). Perhaps some light witticism is intended here. Walking sticks, which ‘permeated masculine leisure’ in the eighteenth century, could be ingeniously combined with all manner of other gentlemanly accessories, from telescopes, pedometers and quill pens with ink and paper, to musical instruments such as violins, clarinets, mouth organs and banjos.17 To judge by the frequency of their survival, flutes concealed within the shafts of walking sticks seem to have been a particularly popular variation on this fashion (see, for instance, Georg Henrich Scherer’s walking-stick flute/oboe from the 1750s; fig.6), evoking just the kind of sociable and spontaneous concert champêtre depicted by Gainsborough.18

Fig.6

Georg Henrich Scherer

Walking-stick flute/oboe, c.1750–7

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.7

Martin Wenner

Flute after J.W. Oberlender, stained boxwood, a=415 Hz, 2015

Photo: Martin Wenner

The delicate precision of the artist’s rendering in this conversation piece allows us to identify the transverse flute in Keable’s hand rather precisely. The standard six holes and single key of the instrument are visible, while the colour suggests it is made from boxwood. The distinctive shape of the bore or interior chamber, especially the bulge at the base of the head-joint, indicates that it was made by Johann Wilhelm Oberlender (1681–1745). This Nuremburg musician was one of the most celebrated makers of the day, suggesting that a discerning Keable sought a quality instrument from the Continent rather than a British-made instrument. Although a German flute would have been considered more fashionable and an indication of good taste, the choice of boxwood over ebony or granadilla, and the lack of ornamental decoration (such as horn or silver rings), shows the prioritisation of quality of sound over costly show. Similarly undecorated instruments are made today in the workshop of Martin Wenner in Singen, Germany (fig.7). These are copied from an Oberlender preserved in the Museo Civico in Modena, which is almost identical to the flute held by Keable.19

Fig.8

Thomas Gainsborough

Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape, detail of William Keable

Photo © Tate

Keable’s choice of flute is indicative of his taste and discernment, but the correctness of his carriage (which Gainsborough went to some lengths to capture with accuracy),20 is no less suggestive of the sitter’s skill on the instrument (fig.8). John Johnson’s Compleat Tutor, first published in 1727, instructed enthusiasts like Keable in the technique and terminology of various musical instruments and, for the flautist, provided a translation from Jacques-Martin Hotteterre’s Principes de la Flûte Traversière (1715).21 For the player of this instrument, ‘one of the most pleasant, and one of the most fashionable’,22 the text, which was republished many times, recommends a stance that accords precisely with that depicted by Gainsborough with regard to the angle of his head, arms, hands and fingers. Indeed, the artist even makes a subtle nod towards the optimum distribution of weight between the flautists’ legs, despite the fact that Keable is seated:

The body, sitting or standing, should be erect, the head rather raised than inclined, and somewhat turned to the left shoulder; the hands high without raising the elbows or shoulders; the left wrist bent inwards, and the left arm close to the body. When standing stand firm, advancing the left foot a little and bearing the weight of the body on the right leg, without constraint, and avoid all motion of the head or body in beating the time. The flute must be held between the thumb and fore finger of the left hand, which must be uppermost; the first and second fingers something more arched than the third; all the fingers of the right hand almost straight; the thumb over against the fourth hole or a little lower; the little finger between the sixth hole and the bottom piece, and the wrist bent a little inward. Keep the flute almost strait, a little inclining to the lower part.23

Gainsborough’s depiction of the vital embouchure of Keable’s mouth similarly conforms to the prescriptions found in the Compleat Tutor:

Tho’ some think this cannot be taught by rules, yet the description of a good master, and method, may facilitate the doing of it. Observe therefore the lips are to be close, except just in the middle, to give passage to the wind, and must be contracted gently, even and smooth rather than pouting out.24

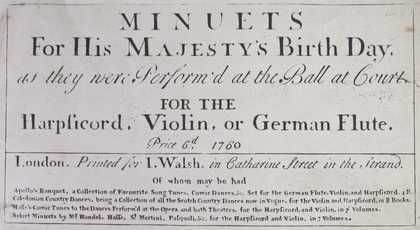

Keable’s evident accomplishment hints at the kind of repertoire he might have been playing to entertain his walking companions. The Compleat Tutor was republished several times over the course of the century as The Muses Delight and Apollo’s Cabinet and offered musical extracts as progressive lessons.25 These include melodies such as ‘The Shepherd’s Invitation Set by Mr Lampe’ and ‘The Shepherd’s Complaint Set by Mr Russel’ which continued to promote the flute’s pastoral associations. Similarly apposite to the outdoor flute-playing of the Gainsborough portrait are the contemporary scores published in pocket-sized formats, such as Minuets for His Majesty’s Birthday published by John Walsh in London in 1760 (fig.9). These chequebook-like volumes, which most frequently drew upon composers at court in London such as Michael Festing and Georg Frederick Handel in melodic dances and opera arias, were designed to fit into a gentleman’s coat pocket and could thus be conveniently transported for just the kind of spontaneous and informal performance depicted by Gainsborough, wherever it might arise.

Fig.9

Minuets for His Majesty’s Birth Day

Pocket-sized score published in London, 1760

University of Cambridge, Cambridge

The context of mid-eighteenth century amateur flute playing allows us to understand Gainsborough’s portrait more completely as an image of masculine refinement. The figure of Keable at play reveals the extent to which the depiction of music-making could invest a portrait with the highly desirable qualities of fashionable taste, sociable spontaneity and, perhaps above all, cosmopolitan savoir faire. Here, after all, in the midst of a scene of remote pastoral calm, was the exquisite depiction of a German instrument, popularised in France, increasingly associated with Italianate musical style, and finding refinement in the hands of an English gentleman.