Fig.1

Thomas Gainsborough

Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape c.1750

By the middle of the eighteenth century, Britain’s status as one of the world’s leading global trading nations was firmly established. The Atlantic region in particular was a focal point for mercantile activity, and the criss-crossing of people and goods within this arena enabled the development of new spheres of social interaction. As a result, the settlement of foreign families in London and provincial centres became a salient feature of the period’s demographic change.1 Gainsborough’s group portrait Peter Darnell Muilman, Charles Crokatt and William Keable in a Landscape c.1750 (Tate T06746; fig.1; hereafter Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape) embodies this coming together of cultures. Together, the men’s family and professional connections encompassed locations as widespread as Scotland, colonial North America, the Netherlands, Germany and Russia. However, in this painting they are dramatised as a tight-knit unit with a strong sense of rapport and social affinity which belies their diverse origins. Although imperial and economic relationships were rarely addressed directly by British artists in the period, this essay seeks to reveal how Gainsborough effectively reconciled such complicating factors through a variety of well-rehearsed representational techniques from his artistic repertoire.2 This process, which can be termed ‘pictorial naturalisation’, could be understood as part of a broader contemporary drive towards ‘glocalisation’, in which the distinctions between ‘local’ and ‘global’ identities became gradually eroded.3

As émigré merchant communities began to spread more widely across the British Isles, the boundaries of these communities were decreasingly defined by space.4 Rather than describing a discrete area populated by merchants, the term ‘merchant community’ came to express something less tangible. Ties of kinship, marriage, fraternity and shared patterns of patronage were at the core of these networks. This kind of union is demonstrated in Gainsborough’s painting, where Muilman and Crokatt represent the familial association between two merchant dynasties; in 1752 the two men became brothers-in-law, following Charles Crokatt’s marriage to Anna Muilman. Beyond this matrimonial alliance, the families moved in the same business circles. Peter Muilman’s uncle, Peter, and Charles Crokatt’s father, James, served together on a committee of merchants formed in the City of London in 1746.5 Peter Muilman’s father, Henry, was also involved in the capital’s closely interlinked commercial community: along with his brother, he was elected to the board of the Russia Company at a meeting in London in 1743; he was also a director of the South Sea Company.6 As heirs apparent in their respective families, the depiction of Muilman and Crokatt together seems to record for posterity the creation of a distinctly patriarchal mercantile genealogy.

While Peter Muilman and Charles Crokatt were evidently connected through these bonds of friendship, family and business, their companion in the portrait, William Keable, was from an altogether different background. Thought to have been born at Nayland in Suffolk,7 Keable travelled to London to train as an artist in the 1740s. He later became a member of the St Martin’s Lane Academy. Given the similarity with Gainsborough’s professional trajectory at this time, it seems highly likely that the two men were acquainted. Moreover, there is a suggestion that Keable and Gainsborough also had a mutual friend in the author Joshua Kirby, another Suffolk man, whose Method of Perspective Made Easy (1754) they both subscribed to.8 In the early part of his career in London, Keable developed something of a reputation as a portrait painter for visiting Carolina merchants; James Crokatt’s business partner in Charles Town (now Charleston), Benjamin Smith, and his wife were among them.9 However, Keable’s standing in this regard seems to have been relatively modest. As Peter Manigault commented during a visit to England from the colonies in 1750, some of Keable’s paintings were ‘very good’, yet in others ‘his Paint seemed to be laid on with a Trowel and looked more like Plaistering than Painting’.10

Fig.2

Thomas Gainsborough

John Plampin c.1752

National Gallery, London

Fig.3

Thomas Gainsborough

A Gentleman with a Dog in a Wood c.1747

Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury, on loan from a private collection

As a fairly minor figure in the London art world, Keable’s appearance in Gainsborough’s portrait is significant in several respects. On the one hand, it formally acknowledges his friendship with Muilman and Crokatt, and therefore reflects the social status enjoyed by young and aspiring British artists – even those of a lower rank. This kind of reading may be extended to Gainsborough, whose portrayals of John Plampin of about 1752 and an unidentified sitter in A Gentleman with a Dog in a Wood of about 1747 express the same air of ‘convivial intimacy’ between artist and sitter (figs.2 and 3).11 Evidence of dealings between the Plampin and Muilman familes,12 who shared a mutual association with Gainsborough, further strengthens the notion of an interconnected milieu of male sociability in which artists and their patrons enjoyed close personal and professional relationships. The inclusion of Keable in Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape may likewise be seen to reify a suggestion of personal and professional kinship between painters, analogous to the bonds that existed between members of the mercantile community. Finally, by imperceptibly adding a local ‘British’ dimension to the collective identity of the trio, Keable’s presence implies a sense of integration between foreign and native communities. In doing so, the portrait suggests that, in the wake of rapid global development, national identity was no longer considered the ‘trump identity’ that it once was, and that other forms of individual or group identity could be far more meaningful.13 As historian Kathleen Wilson has noted, the most significant social relations, or identities, were far more transient and subject to constant re-formation ‘through the practices of everyday life’.14

Fig.4

Thomas Gainsborough

Mrs Mary Cobbold with her Daughter Anne in a Landscape with a Lamb and a Ewe c.1752

Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury

This painting is not the only example of a Gainsborough conversation piece designed to aid the flattering self-presentation of members of the commercial classes.15 In Mrs Mary Cobbold with her Daughter Anne in a Landscape with a Lamb and a Ewe c.1752 (fig.4), Gainsborough introduces an element of performance that clearly resonates with this characterisation of the genre. Here, the female members of a commercial brewing family are depicted in a rural idyll, dressed in fashionable contemporary attire, but styled in the distinctive guise of shepherdesses.16 The pastoral femininity signified by this classical allusion and the overall rusticity of the setting counterbalance any prevailing attitudes of disdain towards newly moneyed members of the eighteenth-century business community, of which the Cobbolds were part.

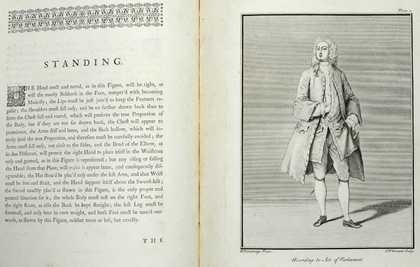

Fig.5

Pages from François Nivelon, Rudiments of Genteel Behaviour, London 1737

Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury

Similarly, Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape fuses an image of contemporary urbanity with the more nuanced pictorial vocabulary of idealised country living. Conforming to the established ‘rudiments of genteel behaviour’, set out in etiquette manuals like François Nivelon’s 1737 publication of that title, the figure on the right adopts the recommended posture for ‘standing’ (fig.5). In doing so, he may be distinguished as ‘amiable, genteel and free in [his] Person … Air and Motions’, and is thus dramatised as a knowing participant in the physical language of politeness.17 At the same time, however, there is a sense of removal from the trappings of contemporary metropolitan life – and critically in this case, the excesses often associated with mercantilism and the commercial world. While it has been suggested that Keable’s role as the flautist implies his proficiency as a musician (and perhaps also his role as music master to Crokatt and Muilman), his portrayal as a rural piper may also be seen as a more oblique classical allusion, namely to Pan, a figure synonymous with the pastoral world of ancient Greek mythology. As the writer and poet Joseph Addison remarked in 1751, ‘the sweetness and rusticity of a Pastoral cannot be so well expressed in any other tongue as in the Greek’.18 By evoking this esteemed pastoral tradition, Gainsborough’s image of the countryside and its mercantile inhabitants is elevated beyond the realm of the everyday; the world of material prosperity is subdued in favour of a more timeless, universal appreciation of nature.

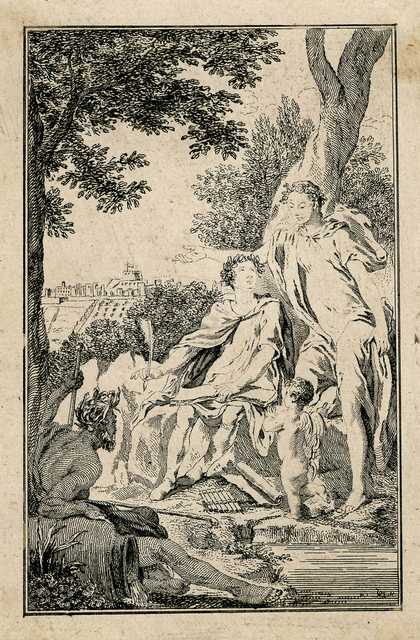

Fig.6

Hubert-François Gravelot

Etched state of an illustration for an unidentified publication, c.1740s

British Museum, London

The period in which Gainsborough was working saw representations of the British countryside become increasingly punctuated by these kinds of classical allusions. The landscapes of John Wootton, George Lambert and Richard Wilson are particularly notable in this regard. However, this development was not simply a condition of fine art, but extended into contemporary graphic art too, and in particular the field of book illustration in which Gainsborough’s early mentor Hubert-François Gravelot was a leading figure. A design by Gravelot for an unidentified publication from the 1740s is an important point of reference here (fig.6). It depicts a poet sitting on a rural bank accompanied by a muse, a putto and a river god. A set of panpipes lies on the floor by his feet. The composition is framed by large trees and contains a distant view of what appears to be a fortified settlement. In its comparable pictorial style and its allusion to the classical or pastoral world, the mode of portraiture crafted by Gainsborough for Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape demonstrates the influence of such visual precedents. Moreover, if, as literary historian Paul Alpers suggests, the ‘pastoral’ is an essentially ‘urban and sophisticated’ form of expression ‘in which the real and the ideal come together’, Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape provides an exemplary model of how the verbal rhetoric of mid-eighteenth-century pastoral was transfigured by Gainsborough into an alternative form of visual representation.19

As well as investing themselves with the trappings of pastoralism in art, the distinctly commercial Crokatt and Muilman families made the countryside an integral part of their real lives. By acquiring residences in rural Essex, and inhabiting spaces in the British countryside, their movements reflect a pattern of consumption that saw mercantile communities embrace the conventions of ‘English gentility as a social insulator’, as the historian I.K. Steele has described it.20 As relatively new inhabitants of these rural locations, it is worth pausing to contemplate what type of landscape is alluded to in Gainsborough’s portrait of Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape. In particular, as John Chu argues elsewhere in this In Focus, it is important to consider the distinction between ‘common land’ and ‘land ownership’, and how this separation of spaces is articulated.21 Certainly, these alternative conditions of land and their derivatives were often expressed in quite different terms by Gainsborough: as expansive pasture for grazing in Mrs Mary Cobbold with her Daughter Anne in a Landscape with a Lamb and a Ewe; as parkland with classical statuary in Mr and Mrs Carter c.1747–8 (Tate T12609); or as an agrarian ideal of land management in Mr and Mrs Andrews c.1750 (National Gallery, London), where the neatly stacked sheaves of wheat, and an overt allusion to Robert Andrews’s huntsmanship in the form of the gun he holds, tell of the specific land they owned and inhabited. In Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape, however, the unusual complexity and painterly development of the landscape element seems to contain several possible meanings, and certainly invites more than one historical perspective.

Fig.7

A View of the Seat of the Late Henry Muilman Esqr at Dagenham in Essex, from A New and Complete History of Essex, Chelmsford 1771

Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury

In the mid-eighteenth century, possessing even a modest landed estate could function ‘as a passport into the governing class’, as historian Stephen Hague observes.22 Indeed, as Hague has suggested, ‘in whatever situation they occupied, gentlemen’s houses were primarily about confirming status’.23 An exterior view of the Muilman Residence at Dagnams (fig.7), which was included as an illustration in the 1771 edition of A New and Complete History of Essex, epitomises the way in which such houses were represented and fêted for this purpose. Significantly, Peter Muilman’s paternal uncle, Peter, appears to have had a role in bringing this work to publication and reputedly obtained the plates for the illustrations.24 The viewpoint chosen to represent Dagnams at this later date positions the house as both a part of, and apart from, the surrounding countryside. A boundary fence subtly demarcates the extent of the manicured garden space where the land gives way to a more rugged agricultural landscape. A row of tall trees, planted in neat succession, appears to serve the same function, continuing the line of the fence.

Although there is no obvious pretension to topographic accuracy in Gainsborough’s portrait of Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape, there are similarities to be drawn with this later engraving of Dagnams. The painting certainly evokes the notion of a rural estate – or at least the boundary of one – and the long avenue of tall trees behind the men, which winds its way into the distance, is reminiscent of how the threshold is demarcated in the print. The appearance of a church tower and distant cottages beyond fields across a valley (presumably symbolic of a nearby village) is a further unifying factor between the print and the painting. While it is important to note that these two images were produced some twenty years apart, and that major developments were made in both landscape design and its associated visual language during this time, cultural historian Stephen Bending’s proposition that ‘gardens by definition mark out their own difference from the productive agricultural land around them’ hints at a universal quality applicable across space and time.25

Interpreted in this way, then, the subjects of Gainsborough’s portrait may be understood as occupying a liminal position between the domestic and natural, private and public. Our gaze is not directed towards the residence we might imagine we would see if we reversed our viewpoint, but towards a broad panorama of the vast and open space beyond. Read in these terms, the absence of a house in the painting rejects the notion of built property as an essential form of iconography to confirm cultural and economic authority. This alternative, outward-looking perspective in many ways echoes the mind-set of the eighteenth-century merchant, for whom traversing frontiers – both nationally and internationally – was a routine part of everyday life. As Bending and Andrew McRae propose in their 2003 book The Writing of Rural England 1500–1800, ‘landscape is not simply experienced from a particular viewpoint, but shaped by a point of view. Indeed, as the latter phrase suggests, a viewpoint, then, is not just the ground on which one stands, but the mental structures and assumptions that enable one to see in a particular way’.26

While the rural conversation piece cannot be exclusively connected to the mercantile classes, or those invested in imperial trade, it was certainly a mode of representation that these individuals bought into. Moreover, for the reasons drawn out elsewhere in this publication, Gainsborough’s particular approach to the genre served a dual function for such clients.27 Displaying economic and social status was clearly a motivating factor for the commission of works like Muilman, Crokatt and Keable in a Landscape, but demonstrating an innate sense of value and moral judgement to legitimise this privilege was undoubtedly also a pressing concern.