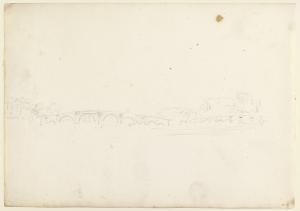

Turner Bequest XCV

47 leaves from a disbound roll sketchbook, originally bound in blue and pink marbled laid paper covers of which only the front one survives (D40344)

The cover made by an unknown maker, without watermark; the leaves of white wove paper made by William Balston and the brothers Finch and Thomas Robert Hollingworth, Turkey Mill, Maidstone, Kent and variously watermarked ‘1797 | J WHATMAN’

Inscribed by Turner in ink ‘Thames from Reading to Walton’ on the remaining cover, top left running vertically

Endorsed in ink by the Executors of the Turner Bequest ‘No 160’ and signed by Henry Scott Trimmer and Charles Turner ‘H. S. Trimmer’ and ‘C. Turner’ and initialled by John Prescott Knight and Charles Lock Eastlake ‘JPK’ and ‘C.L.E.’ inside the cover

The cover made by an unknown maker, without watermark; the leaves of white wove paper made by William Balston and the brothers Finch and Thomas Robert Hollingworth, Turkey Mill, Maidstone, Kent and variously watermarked ‘1797 | J WHATMAN’

Inscribed by Turner in ink ‘Thames from Reading to Walton’ on the remaining cover, top left running vertically

Endorsed in ink by the Executors of the Turner Bequest ‘No 160’ and signed by Henry Scott Trimmer and Charles Turner ‘H. S. Trimmer’ and ‘C. Turner’ and initialled by John Prescott Knight and Charles Lock Eastlake ‘JPK’ and ‘C.L.E.’ inside the cover

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

These leaves, now mounted separately, come from a dismembered sketchbook belonging originally to the group used on or near the Thames from circa 1805. Its views of the river are concentrated around Isleworth and Richmond, and above Cliveden towards Oxford. They have been variously dated between 1806 and 1808 but studies related to Turner’s painting Walton Bridges (Loyd collection)1 possibly exhibited at his Gallery in 1806 would allow a dating of 1805, when the artist was living at Sion (or Syon) Ferry House, Isleworth; see especially Introduction to the Studies for Pictures: Isleworth sketchbook (Tate D05491–D05617; D40568–D40574; D41505; Turner Bequest XC). Other material from the sketchbook overlaps with the Studies book and with others used at Sion Ferry House; Hesperides (1), Hesperides (2) and Wey, Guildford (Tate D05766–D05842; D05844; D40632; D40634; Turner Bequest XCIII; Tate D05485–D05904; D40637; D41506; Turner Bequest XCIV; Tate D06180–D06362; D40594–D40594; D41507; Turner Bequest XCVIII).

From this sketchbook comes what must surely be Turner’s most informative view of Sion Ferry House, with its garden wall and Gothic summer-house and a glimpse of the Thames bank with the dry mouth of the former Duke of Northumberland’s River and its retaining wall in the foreground (D05952; Turner Bequest XCV 48). Turner also made views looking in the opposite direction from the house or summer-house (D05916, D05949; Turner Bequest XCV 12, 45). Together they paint a vivid picture of his adopted territory, and of the changeable, stormy weather in the summer of 1805.

While a number of subjects are near Isleworth, others must have been drawn in the course of a trip along the Thames almost as far as Oxford, in the boat that Turner kept for sketching, painting and fishing. The viewpoints are often from the water. David Hill posits a trip lasting perhaps a month in September or October 1805 when the weather was fine,2 although a view of Shillingford (D05944; Turner Bequest XCV 40) shows the sun declining in the sky to the north-west, indicating midsummer. During the same tour, Turner painted from nature in oil on canvas and as Hill oberves, the oils follow the same topographical range and views like those of Goring and Caversham mirror those in the sketchbook. Turner’s title for the sketchbook, for what it is worth, indicates that he was moving down-river. However, Hill assumes he was going in the opposite direction. In the end, the direction of travel or the order in which the drawings were made seems inconclusive since Turner would have had to go up-river from Isleworth in the first place.

The many pencil drawings from the sketchbook are sometimes slight but always clear and crisp in outline. Turner also added some coloured studies. These retain the freshness and naturalism of the watercolours in the smaller Hesperides (1) and are often bold and gestural in execution, with scratching and stopping out and thumb and finger prints. But they are sometimes more considered in their design, causing debate as to whether they were made on the spot or in the studio. For John Gage, ‘the character of the watercolours is various’,3 implying differences in timing and manner of execution. Gerald Wilkinson sees Turner ‘actually composing his pictures on the spot’,4 Andrew Wilton considers them ‘among the finest of all romantic open-air watercolours’5 while also observing their ‘Poussinesque dignity’6 or ‘strongly classicizing formality of conception’7 and Hill shares similar views while admitting that some of the effects described, such as passing shadows, are too fleeting to capture live in watercolour. To some extent, such transience may be a clever technical illusion and Michael Spender is inclined to think it was sometimes achieved in the studio. The purpose of these watercolours is also debatable. While Spender8 considers them ‘Turner’s first group of fully developed watercolour studies produced for his personal interest and use, rather than as preliminary designs for other works’, it seems equally possible that they had some intermediate function or were meant to be shown; if not exhibited, then perhaps presented to collectors as the basis of commissions or to publishers and engravers for reproduction. In addition, as Hill notes, many of the leaves are ‘creased, dirtied, and battered’, and if this wear and tear occurred in Turner’s studio it would indicate that he made good use of them.

Hill suggests that Turner was planning a series of Thames plates like the aquatints in Samuel Ireland’s Picturesque Views on the River Thames (1792) or William Combe’s History of the River Thames published by John and Josiah Boydell (1794, 1796), which contained plates after Turner’s colleague Joseph Farington, some of which Farington engraved himself. As recently as perhaps 1804, Turner had made a view of Abingdon, from the Thames Navigation (Courtauld Gallery, London)9 for engraving in copper-plate for William Byrne’s Britannia Depicta; a Series of Views, with Brief Descriptions, of the most interesting and picturesque Objects in Great Britain. The print, dated 1 January 1805, appeared in the first part, published in 1806. Farington was among Turner’s fellow contributors to this project, which after Byrne’s death in 1805 was continued until 1810 by his daughter Letitia. A similar publication focused on the rustic Thames, and published independently, could have been on Turner’s mind.

It must have been the beauty of the watercolours in this sketchbook that accounted for its early dismantling. Hill10 believes this was done by Turner himself but there is no surviving proof for this, nor of another possibility that John Ruskin was the perpetrator, as he was in other cases. From the First Loan Collection tour (various venues,11 1869–1931), leaves from this book have been among the most often exhibited of all the Thames watercolours, and to all intents and purposes they have been treated as independent works. Exhibition records are therefore given in this catalogue only for individual leaves. Most of the leaves have numbers in red ink, as typically given by Ruskin, but it is not certain that they record the original order of contents. Finberg, who found the leaves loose, used them as the basis for his own ‘page’ numbers. However, some sheets have different numbers in pencil on the back. Finberg included, as ‘pages 43 and 44’, two leaves with coloured sketches of stags (D05947 and verso D40274, D05948); these are on different paper, show evidence of having been cut down and seem not to belong to this sketchbook. It is doubtful if all the original contents formed part of the Turner Bequest or are at Tate. Hill lists a group of seven or perhaps eight watercolours of Thames subjects that on stylistic grounds might have belonged to the book, but this cannot be confirmed and they show discrepancies in size.

While most commentators have seen this former sketchbook (and especially the watercolours) as evidence of a trend to naturalism in Turner’s work, Hill’s treatment of its content is by far the most detailed and informative, with many new identifications of Turner’s subjects, supported by his own photographs, and insights into how Turner’s use of the book dovetailed with his work in other media at the same time. In addition, Hill arranges the contents into a notional sequence in topographical order, beginning with a group of views from Kew Bridge to Richmond Bridge and proceeding thence up-river from Walton Bridge to Dorchester. He places the remaining unidentified subjects in a third and separate group. He numbers this arrangement (in Roman numerals) and provides a concordance. However, there can be no certainty that Turner used the book in a methodical topographical order even if all the subjects could be identified, and the likelihood of missing leaves makes reconstruction of the original order speculative at best. Moreover, as stated above, Turner’s title indicates a down-river sequence of subjects. For these reasons, and to avoid yet another concordance, the present catalogue retains Finberg’s sequence.

Technical notes

How to cite

David Blayney Brown, ‘Thames, from Reading to Walton sketchbook 1805’, sketchbook, February 2009, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www