Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Self-Portrait 1914

Oil paint on canvas

410 x 305 mm

National Portrait Gallery, London

Photo © National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig.1

Spencer Gore

Self-Portrait 1914

National Portrait Gallery, London

Photo © National Portrait Gallery, London

Gore was born on 26 May 1878 in Epsom in Surrey, the fourth child of Spencer William Gore (1850–1906) and Amy Gore (née Smith, William’s senior business partner’s daughter). His father was a partner in Smith, Gore & Co. (now Smiths Gore), who were land agents to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners in Yorkshire; he was also winner of the first Lawn Tennis Championship at Wimbledon in 1877. Gore’s childhood was spent in Holywell, Kent. He attended Harrow School from 1892 to 1896 where he discovered his love of art, winning the first Yates Thompson Prize for drawing. He also inherited his father’s sporting abilities, excelling in cricket while at school.

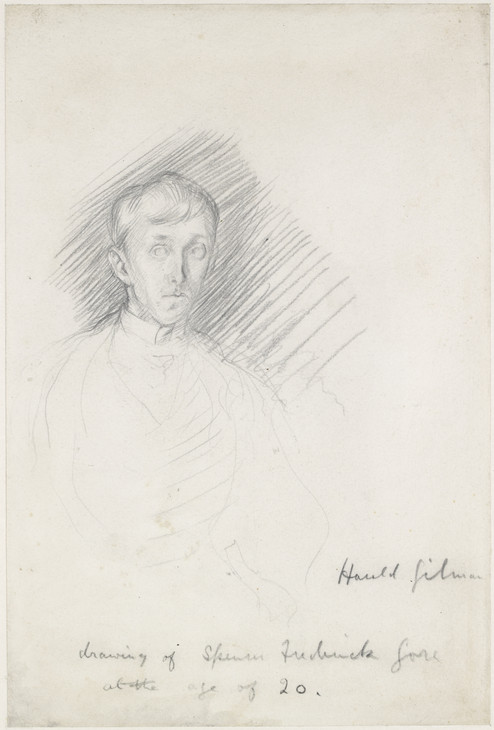

Enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art from 1896 to 1899, Gore’s contemporaries included Gilman (fig.3), Augustus John, Wyndham Lewis, William Orpen and Albert Rutherston, with many of whom he made lasting friendships. Gore was taught by Frederick Brown, Philip Wilson Steer and Henry Tonks. Although not much of Gore’s early work survives, some landscapes, such as The Cricket Match c.1908 (The Hepworth Wakefield),4 reveal the influence of Steer’s English impressionism of the late 1880s and early 1890s; Steer, in turn, had been inspired by Claude Monet as well as neo-impressionists such as Georges Seurat.5

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Portrait of Spencer Frederick Gore 1898–9

Pencil on paper

275 x 183 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum

Fig.3

Harold Gilman

Portrait of Spencer Frederick Gore 1898–9

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum

The three early works in the Tate collection were presented by Albert Rutherston (Tate N06016, N05263 and N05307). Gore and Rutherston were close in the early 1900s and Rutherston painted a portrait of his friend in quite a humorous pose in 1902 (National Portrait Gallery, London).9 It was through Rutherston that Gore met Sickert when the two were travelling in Normandy in 1904. They were staying in the Normandy village of Cany;10 Sickert was nearby in Dieppe, where he had been living intermittently since 1898. Rutherston later remembered that ‘Gore had a great admiration for Sickert’s work’ and so ‘the temptation to act as his cicerone’ meant that the pair travelled to Dieppe ‘where we spent two delightful days and evenings in Sickert’s company’.11 Gore and Rutherston spoke enthusiastically about the new generation of artists who were emerging from the Slade: John, Orpen, Lewis, Gilman, Gwen John, Ambrose McEvoy and Edna Clarke Hall. Sickert’s interest was ‘aroused’ by these tales of exciting developments in the London art world,12 and Gore’s personality appealed to him; he promised that he would exhibit at the winter New English Art Club and also visit these young artists in London.

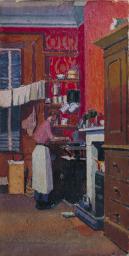

Sickert returned to live in London in 1905 after an absence of almost seven years, renting a studio at 8 Fitzroy Street;13 Gore and Rutherston were nearby with studios at 21 and 18 Fitzroy Street respectively.14 Gore and Sickert began painting and drawing together, sometimes sketching in the Bedford music hall in Camden. Gore acquired from Sickert an enthusiasm for painting everyday urban life, especially nudes in intimate interiors; Sickert encouraged Gore to paint in the studio rather than en plein air as was the more typical impressionist practice. In works such as Sickert’s Mornington Crescent Nude: Contre-Jour c.1906 (private collection)15 and Gore’s Behind the Blind 1906,16 we can see that at this time both artists were using the same studio, furniture and models.

During this period in which they often painted together, Sickert was inspired by Gore to adopt a slightly brighter palette and to use a more painterly technique, building up his painting in dabs of colour with a dryer brush. As he later remarked, ‘To come down to historical fact, I may as well say that it is my practice that was transformed from 1905 by the example of the development of Gore’s talent’.17 In 1909 Gore moved to 31 Mornington Crescent with Sickert close by at 6 Mornington Crescent.18 The two were firm friends throughout their lives and were best man at one another’s weddings.

Sickert also judged that the first group of modern artists in England were not influenced by him, but rather ‘by Mr. Gore and Mr. Lucien Pissarro’.19 It was in 1904 that Gore first met Lucien Pissarro, whose work, along with that of his father Camille, he would have seen at the NEAC exhibitions in the 1890s when they were the forerunners of neo-impressionism. As Sickert said of Lucien:

Mr. Pissarro, holding the exceptional position at once of an original talent, and of the pupil of his father, the authoritative depository of a mass of inherited knowledge and experience, has certainly served us as a guide, or, let us say, a dictionary of theory and practice on the road we have elected to travel.20

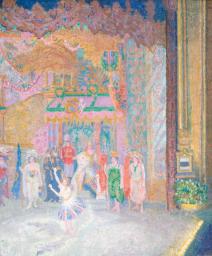

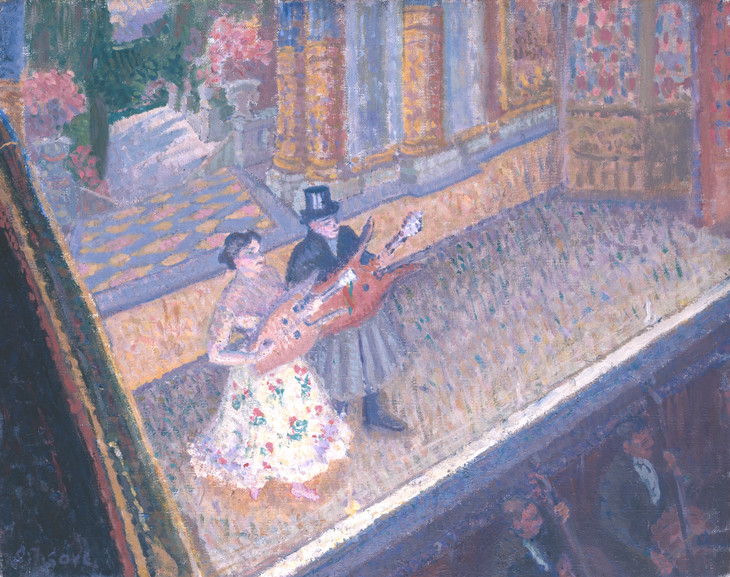

Several of Gore’s works, such as Rule Britannia (Tate T06521) and Inez and Taki (Tate N05859, fig.4), have a neo-impressionist flavour with bright pastel colours and pointillist dabs of colour. The art critic Frank Rutter remarked that ‘Steer excelled in painting the wide-open spaces of England. Pissarro gave clear and more intimate views of her copses and her orchards.’21 The influence of Pissarro’s more intimate landscapes can be seen in some of Gore’s landscapes such as The Garden, Hertingfordbury 1909 (fig.5). In 1910 Gore remarked that neo-impressionism ‘was not a great success because it made a painting very mechanical and took a long time to do’,22 but he clearly adopted certain of its techniques and made them his own.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Inez and Taki 1910

Oil paint on canvas

support: 406 x 508 mm; frame: 608 x 710 x 52 mm

Tate N05859

Purchased 1948

Fig.4

Spencer Gore

Inez and Taki 1910

Tate N05859

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Garden, Hertingfordbury 1909

Oil paint on canvas

410 x 510 mm

Fife Council Libraries & Museums: Kirkcaldy Museum & Art Gallery

Photo © Antonia Reeve

Fig.5

Spencer Gore

The Garden, Hertingfordbury 1909

Fife Council Libraries & Museums: Kirkcaldy Museum & Art Gallery

Photo © Antonia Reeve

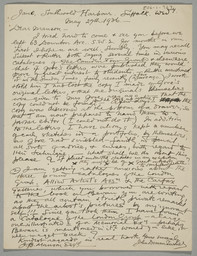

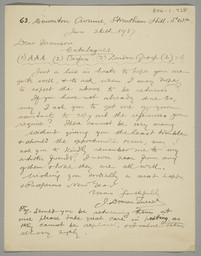

Gore first exhibited at the NEAC in 1906, but James Bolivar Manson recollected that by that time the club ‘had already found its respectable level; it had reached a point of safety. It was too tired or too wise to venture further.’23 This led Gore and Sickert to form the Fitzroy Street Group in 1907 and the Camden Town Group in 1911 and also to help Frank Rutter set up the Allied Artists’ Association in 1908. Gore was also a regular exhibitor at the Paris Société des Artistes Indépendants from 1906 until 1910.24 From 1908 to 1913 he taught drawing by correspondence to the deaf amateur artist John Doman Turner (1872/3–1938), with a series of forty-two letters in total, held in a private collection.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Gauguins and Connoisseurs 1911

Oil paint on canvas

838 x 717 mm

© Private collection

Fig.6

Spencer Gore

Gauguins and Connoisseurs 1911

© Private collection

In January 1912 Gore married Mary Johanna Kerr, known as ‘Mollie’, and moved to 2 Houghton Place, Mornington Crescent (see Tate T03561). By this time he was becoming increasingly affiliated with the more progressive modern artists in England, working on a commission to provide mural decorations for the avant-garde nightclub the Cave of the Golden Calf alongside Ginner, Lewis, Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill. His mural study (Tate T00446) shows the influence of Gauguin’s type of ‘primitivism’, as well as an increasing interest in modern painterly forms of expression, most likely inspired by Paul Cézanne, whose work Gore said had ‘wonderful gravity’.28

Gore produced some of his most modern work, such as The Cinder Path (Tate T01960) and The Beanfield, Letchworth (Tate T01859), from August to November 1912 while staying at Gilman’s house at 100 Wilbury Road, Letchworth Garden City, in Hertfordshire, where Gore’s daughter was born in October (fig.7). Although Gore was not a permanent resident of one of the new Garden Cities, he was evidently attracted by the modern ideas of its proponent Ebenezer Howard. As the art historian Ysanne Holt writes, ‘Howard’s solution to the deteriorating inner-city conditions, building on widespread anti-urbanism and endemic rural nostalgia ... was intended to resolve the traditional town or country dilemma’.29 The fusion of nature with industry is shown in The Beanfield, Letchworth with its geometric patterns and non-realistic colours marking out the field and the factory smoke. In the four-month period in which Gore stayed at Gilman’s house he produced at least twenty-three paintings.30

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Harold Gilman's House at Letchworth 1912

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 760 mm

Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Photo © Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Fig.7

Spencer Gore

Harold Gilman's House at Letchworth 1912

Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Photo © Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Letchworth Station 1912

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

National Railway Museum, York

Photo © National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

Fig.8

Spencer Gore

Letchworth Station 1912

National Railway Museum, York

Photo © National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

As the critic J. Wood Palmer later wrote, Gore ‘was an innovator’ who ‘was in every instance the first to seize on the new movements from France, to examine and assimilate them’.31 His interest in the work of Cézanne and André Derain is reflected in the work of this period. Gore was, significantly, the only member of the Camden Town Group to exhibit as part of ‘the English Group’ in Fry’s Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition at the Grafton Galleries from October 1912 to January 1913, where he showed his recent work Letchworth Station 1912 (fig.8) and also The Cinder Path when the exhibition was extended.32

Displaying his often noted powers of diplomacy, in 1913 Gore brought together the fractured artistic groupings for an Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others at the Brighton Public Art Galleries from December 1913 to January 1914. The Camden Town and Fitzroy Street groups occupied the first two rooms, and the ‘Cubists’ – including Lewis, Epstein, David Bomberg, Frederick Etchells, Edward Wadsworth and C.R.W. Nevinson – the third. Gore had even tried to include the Bloomsbury Group, but Fry wrote to him that it was too soon ‘after so violent a rupture’ with Lewis over a disputed commission.33

Gore held one solo exhibition in his lifetime, Paintings by Spencer F. Gore, at the Chenil Gallery in Chelsea from March to April 1911, at which he showed music-hall scenes, nudes and landscapes. In 1913 he held a joint exhibition Paintings by Spencer F. Gore & H. Gilman at the Carfax Gallery in January, was part of the jury for the NEAC, and showed works at Rutter’s Post-Impressionists and Futurists exhibition at the Doré Galleries in October.

In the summer of 1913 he and his wife and daughter moved to 6 Cambrian Road in Richmond, where he produced thirty-two paintings. His son Frederick was born there in November. Gore made eight more paintings while visiting Somerset that year, creating forty paintings in total in the last six months of his life.34 His painting outdoors in Richmond Park in the cold and wet winter months brought on pneumonia, of which he died on 27 March 1914. Many tributes were paid to the artist, among them Lewis stated in Blast that Gore’s ‘leisureliness and confidence were infectious’ and that:

Had he lived, his dogged, almost romantic industry, his passion for the delicate objects set in the London atmosphere around him, his grey conception of the artist’s life, his gentleness and fineness, would have matured into an abundant personal art, something like Corot and Gessing [sic].35

Lewis felt that some of Gore’s work ‘towards the end belonged rather to this present movement than to any other’.36 Sickert wrote:

It is my privilege to have observed at close quarters the development of Spencer Frederick Gore, from what I may perhaps call the coming of age of his talent in 1906, to its close in 1914 ... In his painting was made manifest colour, and not merely colours ... He attained to exquisiteness in touch. Expression descended like snowflakes on his canvases, varied, adequate, and economical. He painted with the reticence and the measure of the great gentleman that he was.37

A memorial exhibition, Paintings by the Late Spencer F. Gore, was held at the Carfax Gallery in February 1916.

Notes

Frederick Gore, Spencer Gore in Richmond, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Richmond, Surrey 1996, p.8.

For more information, see Robert Upstone, ‘“The Cubist Room” and the Origins of Vorticism at Brighton in 1913’, in The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2011, pp.27–33.

Walter Sickert, ‘Spencer Frederick Gore’, in Paintings by the Late Spencer F. Gore, exhibition catalogue, Carfax Gallery, London 1916, p.2, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, pp.402, 403.

Reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (48).

Reproduced in Ysanne Holt, ‘An Ideal Modernity: Spencer Gore at Letchworth’, in David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds.), The Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past 1880–1940, New Haven and London 2002, fig.35, p.93.

Frederick Gore, Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1974, p.6.

National Portrait Gallery NPG 3320; reproduced in R.M.Y. Gleadowe, Albert Rutherston, London 1925, pl.3, and National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait.php?sText=gore+rutherston&submitSearchTerm_x=6&submitSearchTerm_y=12&OConly=true&search=sp&firstRun=true&rNo=0 , accessed September 2009.

Frederick Gore and Richard Shone, Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay, London 1983, [p.3].

Albert Rutherston, ‘From Orpen and Gore to the Camden Town Group’, Burlington Magazine, vol.83, no.485, August 1943, p.202.

Last known whereabouts Christie’s, 7 March 1986, lot 220. Reproduced in Baron 2000, no.27 and Baron 1979, no.9.

J.B. Manson, ‘Introduction. Rooms I–II’, in Exhibition of the Work of English Post Impressionists, Cubists and Others, exhibition catalogue, Public Art Galleries, Brighton 1913, p.5.

Spencer Gore, ‘Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh &c., at the Grafton Galleries’, Art News, 15 December 1910, pp.19–20.

Nicola Moorby, ‘Gauguins and Connoisseurs’, in Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008, p.59.

Catalogue entries

How to cite

Helena Bonett, ‘Spencer Gore 1878–1914’, artist biography, September 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www