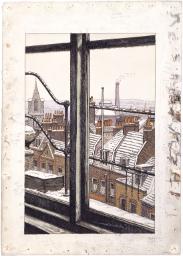

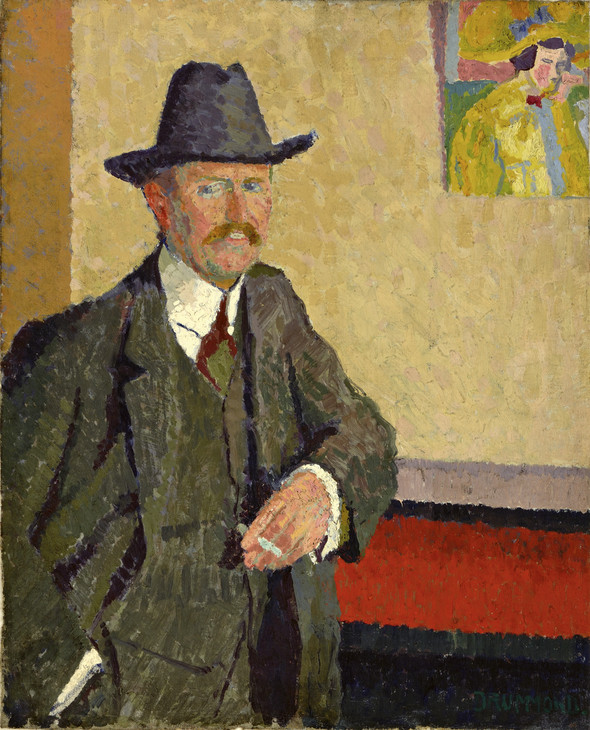

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

Charles Ginner 1911

Oil paint on canvas

603 x 490 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.1

Malcolm Drummond

Charles Ginner 1911

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Isaac Charles Ginner was born in Cannes in the south of France on 4 March 1878.3 He was the third of four children of Isaac Benjamin Ginner (died 1895), from Hastings in Sussex, and Lydia Adeline Wightman, who had lived in London and was of Scottish descent. Ginner’s father established the Pharmacie Ginner in Cannes,4 and his elder brother, Ernest Wightman Ginner, later became a doctor with a practice on the Riviera. Ginner’s eldest brother had died in infancy. His youngest sibling, Ruby Mary Adeline Ginner (later Dyer), became a dancer and dance teacher; many of Ginner’s works were in her collection.5

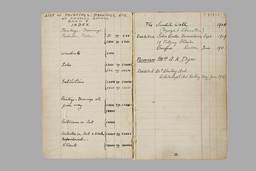

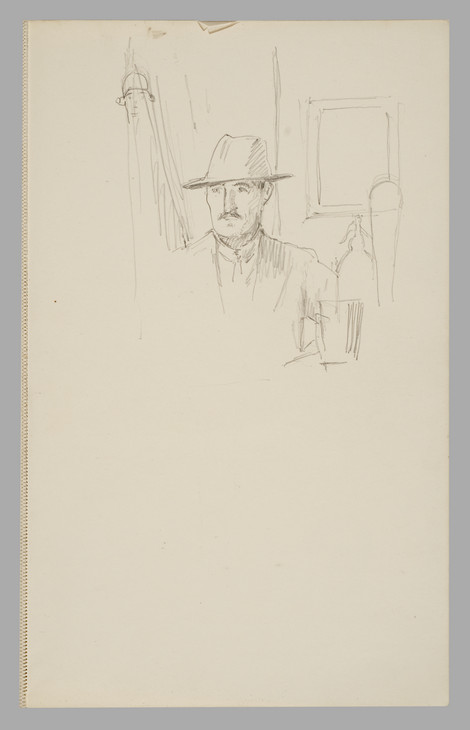

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

Study for 'Portrait of Charles Ginner' c.1911

Graphite on sketchbook paper

354 x 217 mm

Tate Archive TGA 8915

Purchased from Joyce Mills, September 1989

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Fig.2

Malcolm Drummond

Study for 'Portrait of Charles Ginner' c.1911

Tate Archive TGA 8915

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

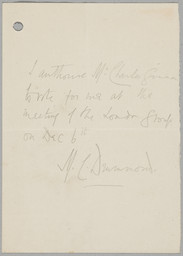

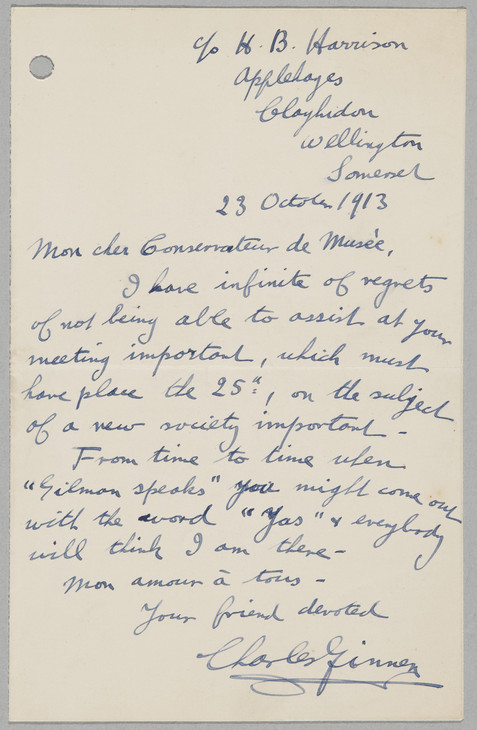

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 23 October 1913

Tate Archive TGA 806/10/6

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.3

Charles Ginner

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 23 October 1913

Tate Archive TGA 806/10/6

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Ginner was educated in Cannes at the Collège Stanislas. At the age of sixteen he contracted typhoid and double pneumonia and was sent to recuperate on a long sea voyage on his uncle Charles Harrison’s tramp steamer in the Mediterranean and South Atlantic.6 Upon returning to Cannes, he spent time working in an engineer’s office before moving to Paris at the age of twenty-one where he was employed in an architect’s office from 1899 until 1904.7

Early style and inspiration

The former director of the Tate Gallery and friend of Ginner, John Rothenstein, wrote about the artist that: ‘For as long as he could remember he wished to be a painter, but he had to overcome the opposition of his family’.8 With financial help from his uncle, Ginner eventually enrolled at the Académie Vitti in Paris in 1904. During his time at art school he earned money as a magazine illustrator, creating some highly detailed, ironic depictions of lascivious gentlemen in decadent Parisian scenes.9 He studied at the Académie until 1908 firstly under the French artist Paul Jean Gervais (1859–1936) and later the Spanish painter Hermen Anglada-Camarasa (1871–1959), as well as briefly studying in 1905 at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.10 He may have learnt to use bright colours and impasto from Anglada-Camarasa;11 a fluid handling of thick paint can be seen in Ginner’s earliest known oil paintings, The Sunlit Wall 1908 (private collection),12 Tache Décorative – Tulipes 1908 (private collection)13 and Girl at an Easel c.1908–9 (private collection).14 This style was short-lived, however, as he soon developed the unique system of methodically applying thick paint in small brushstrokes, which he continued with throughout his life, as his student Marjorie Lilly recollected:

[Ginner] drew in his picture, faintly but carefully, then applied a thin colour wash of approximately the right colours, using turpentine so that it dried quickly. Then he started his real painting with a quantity of rather small, flat brushes and in his methodical way working from left to right across the canvas, finishing the picture in one very thick coat of paint. His aim was to complete this second coat without any corrections.15

While still resident in Paris, Ginner contributed to his first London exhibition: the open-submission Allied Artists’ Association at the Royal Albert Hall in 1908. The organiser, Frank Rutter, later recalled:

Few people took much notice of his work when it was first shown here in 1908, but several artists were literally attracted by his lavish use of pigment, and, the canvas being still wet, took away samples of his paint in their finger-nails. Some few, however, approached his work with more respect, and I well remember Spencer Gore coming up to me before the Ginners and saying with conviction, ‘This man is a painter.’16

In April of the following year Ginner travelled to Buenos Aires in Argentina.17 The art historian Malcolm Easton states that Ginner held a joint exhibition in September at the Salón Costa in Buenos Aires with a fellow student from the Académie Vitti, the Danish painter Dora Erichsen (died 1943),18 where he sold at least five paintings.19 The art historian Wendy Baron reasons that the two probably travelled to and from Argentina together,20 and that Dora was most likely the married woman described in Benjamin Fairfax Hall’s first-hand account of Ginner:

He never married and adopted a slightly cynical attitude towards sex, affecting to regard his mistress as a constitutional necessity like the T.C.P. with which he gargled every morning. Actually, he was much in love as a young man with a woman who preferred to marry someone else. The marriage was not a success and would have been disastrous for the two daughters born of it, had not Ginner, who had a great fondness for children, made himself responsible for their education and welfare. Perhaps he never quite recovered from his early love, and this secret in an otherwise simple life may account for a reticence and shyness surprising in someone whose work was so self-assured as to be unaffected by changing tendencies in art.21

By the time Dora became known in Fitzroy Street circles, she was the wife of a physician, Dr Alfred Victor Sly.22 Harold Gilman painted her in Mrs A. Victor Sly c.1914–15 (Wakefield Art Gallery).23 In A Little Cheque 1914 (Sotheby’s),24 Walter Sickert depicted Dora and Ginner’s financial arrangement as described by Fairfax Hall. Her first husband died on 1 May 1920 and on 29 December 1921 she married a solicitor, Robert Leo Fulford. Dora was given many works by Ginner over the years,25 and Baron argues that she is the sitter in Ginner’s The Girl Philosopher 1929 (Christie’s).26 Dora may also be the female artist in Ginner’s Girl at an Easel, which was painted in South America and depicts a pale-faced, blonde-haired young woman painting at an easel.27

The Camden Town Group and post-impressionism

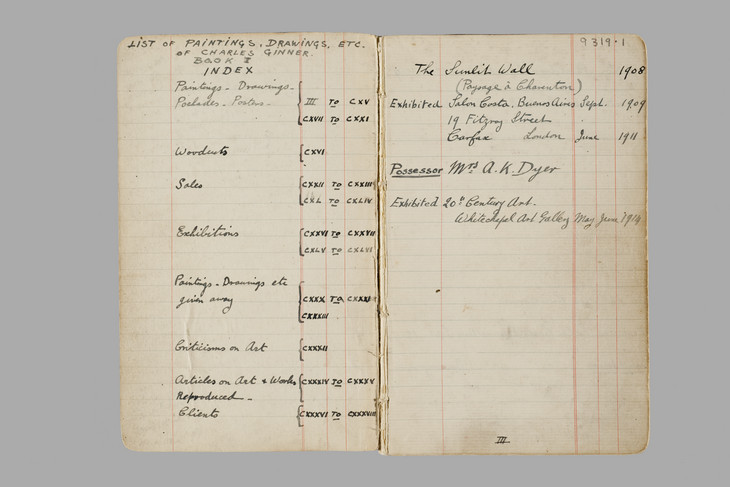

At the end of 1909 Ginner moved to London, where his mother and sister had relocated following the mother’s remarriage.28 Around 1910 he began recording his paintings and drawings in a series of four notebooks in which is listed the titles, dates and sizes of works, as well as where they were exhibited and to whom they were sold, exchanged or given away (fig.4).29 He backdated his records to 1908, where the first oil painting is listed. The notebooks reveal that Ginner continued to exhibit abroad after settling in London, including at the Salon des Indépendants and Roger Fry’s Exposition de quelques artistes indépendants anglais at the Galerie Barbazanges in Paris in July 1912, as well as in Antwerp in Belgium (1911) and Switzerland (1918), as well as many towns and cities across Britain.

In 1910 Ginner was invited to be part of the Hanging Committee for the third exhibition of the Allied Artists’ Association. The committee was alphabetically chosen, and so Ginner met Gilman and Gore. The three became firm friends, and Rutter believed this was the reason why Ginner permanently remained in London.30 It might also have been that he met Sickert in France who advised the move to London.31 Ginner first lived with his mother in Prince of Wales Mansions by Battersea Park, with a studio in Tadema Street, Chelsea.32 Around 1911 he moved to 3 Chesterfield Street (now Crestfield Street) by King’s Cross Station, close to Gore and Gilman in Camden Town.33

As Rothenstein noted, ‘Ginner, one of the most consistent painters of the time, possessed a knowledge of Parisian theory and practice approached by very few of his English contemporaries’.34 In the autumn of 1910, Ginner accompanied Gilman to Roger Fry’s seminal exhibition, Manet and the Post-Impressionists.35 With Rutter the two also visited Paris,36 where at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune they saw ‘a room entirely decorated with the works of Van Gogh, a sight unsurpassed in beauty and intensity’.37 Van Gogh was a great inspiration to Ginner throughout his career, influencing his use of bright colours, thick paint and occasionally a more expressive style, as seen in Victoria Embankment Gardens 1912 (Tate T03841). The critic of the Art News wrote of the brightness of Ginner’s works on display in the first Camden Town Group exhibition:

For sheer glory of colour it is difficult indeed to surpass Mr. C. Ginner. One hesitates to use the phrase ‘crushed jewels,’ which has been so often applied to Monticelli, but ‘The Sunlit Wall’ really glows like jewels themselves. It is quite Bacchic in its voluptuous beauty.38

Ginner assimilated van Gogh’s realist creed, and a photograph of him from the late 1940s shows him reading the 1918 edition of the Dutch artist’s letters.39

Although a photograph from c.1911–12 shows him painting en plein air,40 Ginner generally made sketches from nature, making notes in the margins about particular colours, which he then squared up for transfer to canvas. He used a homemade viewfinder, 11 x 9 cm, subdivided with black and white cotton to find his compositions.41 He also made small oil sketches, each recorded as a ‘pochade’ (pocket sketch) in his notebooks.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Leicester Square 1912

Oil paint on canvas

642 x 559 mm

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Fig.5

Charles Ginner

Leicester Square 1912

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

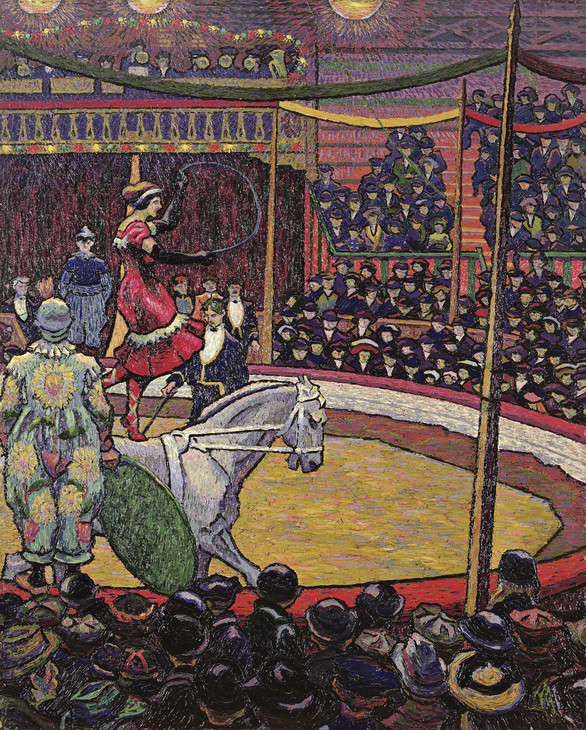

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Circus 1913

Oil paint on canvas

762 x 610 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.6

Charles Ginner

The Circus 1913

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

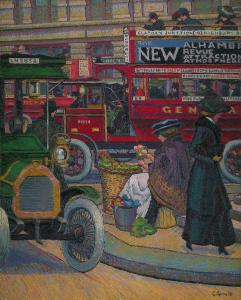

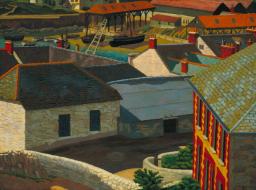

Around 1911 Ginner began painting the central London scenes for which he is most famous. These include The Café Royal 1911 (Tate N05050), Leicester Square 1912 (fig.5), Victoria Embankment Gardens 1912 (Tate T03841), Piccadilly Circus 1912 (Tate T03096), The Circus 1913 (fig.6), London Bridge 1913 (Museum of London),42 The Sunlit Square, Victoria 1913 (Atkinson Art Gallery, Southport),43 The Angel, Islington 1913 (private collection)44 and The Fruit Stall 1914 (fig.7). He continued to depict similar scenes throughout his career, as in The Church of All Souls, Langham Place, London 1924 (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge)45 and The Albert Memorial 1935 (Southampton City Art Gallery).46

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Fruit Stall, King's Cross 1914

Oil paint on canvas

654 x 559 mm

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.7

Charles Ginner

The Fruit Stall, King's Cross 1914

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund

© Estate of Charles Ginner

As well as painting central London, Ginner also created a ‘historic series’ of ‘the industrial cities of Yorkshire’.49 He visited Leeds with Gilman for the first time in 1913. Rutter had moved there to work at Leeds Art Gallery and had organised an exhibition of post-impressionist painting with the Vice-Chancellor of Leeds University, Michael Sadler, who later owned several of Ginner’s works. Ginner painted many industrial scenes of Leeds, such as Leeds Canal 1914 (Leeds City Art Gallery)50 and The Barges, Leeds 1916 (Southampton City Art Gallery),51 and during the war depicted soldiers in a Leeds hospital in Roberts 8 1916 (fig.8), painted before he became an official war artist.52 According to his notebooks he also gave lectures, including a talk on ‘Modern Art and the Future’ on 27 September 1915 at the Leeds Art Club.53

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Roberts 8 1916

Oil paint on canvas

482 x 730 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Tate

Fig.8

Charles Ginner

Roberts 8 1916

Private collection

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Tate

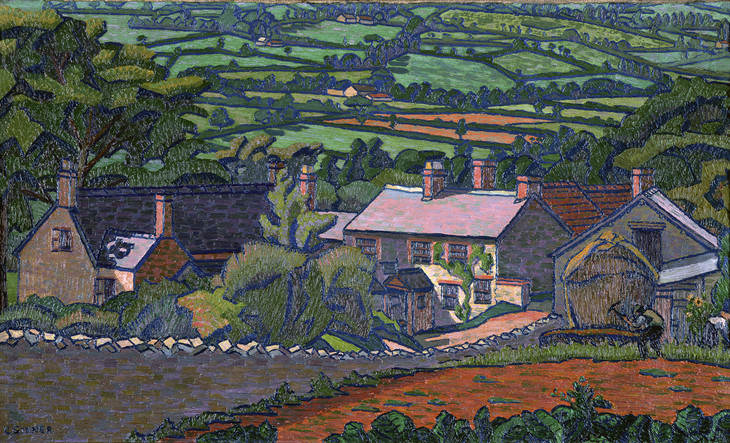

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Clayhidon 1913

Oil paint on canvas

384 x 639 mm

Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, Devon, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.9

Charles Ginner

Clayhidon 1913

Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, Devon, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

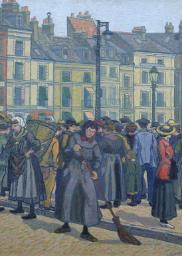

Ginner was not just a painter of urban scenes. In the late summer of 1912 he stayed at Harold Bertram Harrison’s farm, Applehayes, with Gore and Robert Bevan. He visited again in 1913 and 1914.54 There he painted works including West Country Landscape 1912 (private collection),55 North Devon 1912 (private collection),56 Landscape with Farmhouses c.1912–13 (Manchester City Art Galleries)57 and Clayhidon 1913 (fig.9). Two works from the 1912 trip, North Devon and Rain on the Hill (private collections),58 were exhibited along with his famous London scene, Piccadilly Circus (Tate T03096), at the third Camden Town Group exhibition in December that year. Following his sister’s move to Boscastle in Cornwall around 1915 he visited her and the area often, painting works such as Hartland Point from Boscastle 1941 (Tate N05306).

‘Neo-Realism’

On 1 January 1914, Ginner published a manifesto on ‘Neo-Realism’ in the New Age. The article was republished in April in the catalogue of his and Gilman’s exhibition at the Goupil Gallery, representing their combined philosophy.59 The pair had also exhibited under this title in the Allied Artists’ Association exhibition in July the previous year. Ginner began:

All great painters by direct intercourse with Nature have extracted from her facts which others have not observed before, and interpreted them by methods which are personal and expressive of themselves – this is the great tradition of Realism.60

He felt, however, that some of his contemporaries were producing work that simply imitated the innovations of the great realists Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin and van Gogh:

The Academic painters merely adopt the visions which the creative artists drew from the source of nature itself. They adopt these mannerisms, which is all they are capable of seeing in the work of the creative artist, and make formulas out of them.61

For Ginner ‘Neo-Realism’ challenged this formulaic art:

To this new Academism, which will eventually destroy Art ... we must oppose a young and healthy realistic movement, a New Realism, i.e., ‘Neo-Realism’.62

He also described his views on painterly technique:

A pictorial work of Art must be a complete expression of the artist in relation to Nature, and must result in a strong and solidly built up work to be of any lasting purpose. Good craftsmanship must be the natural result of a strong, forcible, and deliberate self-expression. An artist who cannot go beyond a sketch is but a poor artist. Neo-Realism by its very ideals finds itself opposed to the slap-dash, careless, and slick painting which has been and is still so much in vogue.63

Ginner’s article received a detailed response in the New Age from the critic and philosopher T.E. Hulme who rejected the view that realism was the only viable art form, favouring abstraction instead:

It is true, then, that an artist can only keep his work alive by research into nature, but that does not prove that realism is the only legitimate form of art.

Both realism and abstraction, then, can only be engendered out of nature, but while the first’s only idea of living seems to be that of hanging on to its progenitor, the second cuts its umbilical cord.64

Sickert responded ironically to Ginner’s article:

Have Mr. Ginner and Mr. Gilman reflected that, when they put their heads between the sandwich-boards of this or any classification, they will have to carry the blasted boards about for another thirty or forty years?65

Lucien Pissarro was likewise reticent about the term, writing to James Bolivar Manson in November 1913, ‘I fail to understand why some of them have taken the title of Neo-Realist – I fear they don’t quite know where they are going and as true opportunists want to be ready to turn with the wind.’66

In a later review of the New English Art Club, Sickert complimented the smooth and tonal work of Henry Lamb, criticising the use of impasto and bright colours:

Mr. Lamb is not only a great talent, but a great talent under the guidance of a clear and educated brain. He has never been, for a moment, the dupe of technical pedantries. He knows, for instance, that it is a trivial thing to spend a life-time in an effort after intrinsic brightness of paint. He knows that the brightest colours will fade. He knows that there is a strict limit to the advantages of impasto. He knows that, firstly, excessive impasto is not even durable. He knows that impasto is not in itself a sign of virility. He knows even that it is, when practised as an aim in itself, only another subterfuge. Intentional and rugged impasto, from the fact that each touch receives a light and throws a shadow, so far from producing brilliancy, covers a picture with a grey reticulation and so throws dust in the eyes of the spectator, and serves, to some extent, to veil exaggerations of colour or coarseness of drawing. It is a manner of shouting and gesticulating and does not make for expressiveness or lucidity.67

Ginner and Gilman saw this as a veiled attack on their manner of painting. Ginner deftly responded, ‘Sir, – Paint is thicker than turpentine. In answer to Mr. Sickert I have but one statement to make: I shall paint as thick as I damn well please.’68 Despite these differences, Ginner’s statement on realism can be seen as a manifesto for many members of the Camden Town Group:

Each age has its landscape, its atmosphere, its cities, its people. Realism, loving Life, loving its Age, interprets its Epoch by extracting from it the very essence of all it contains of great or of weak, of beautiful or of sordid, according to the individual temperament. Realism is thus not only a present intimate revelation of its own time, but becomes a document for future ages. It attaches itself to history.69

Later groupings

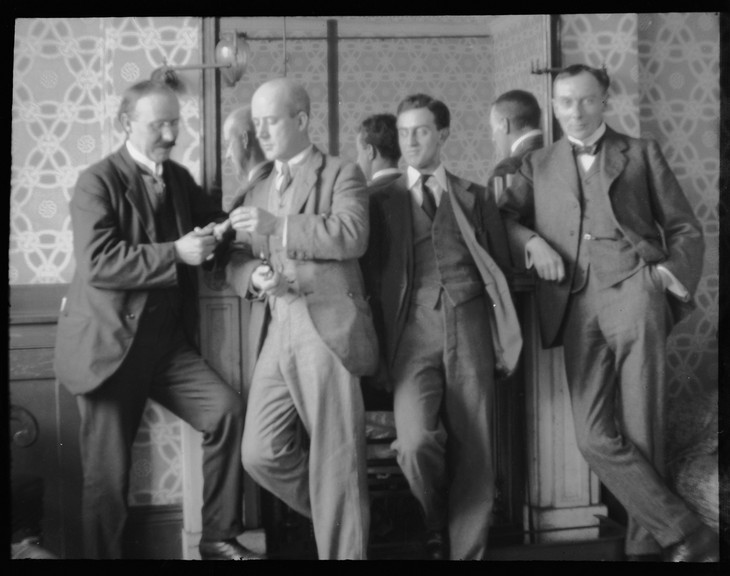

Alvin Langdon Coburn 1882–1966

The Cumberland Market Group c.1915 from left to right: Charles Ginner, John Nash, Robert Bevan and Harold Gilman

Negative, gelatine on nitrocellulose roll film

90 x 120 mm

Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Fig.10

Alvin Langdon Coburn

The Cumberland Market Group c.1915 from left to right: Charles Ginner, John Nash, Robert Bevan and Harold Gilman

Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Alvin Langdon Coburn 1882–1966

The Cumberland Market Group c.1915 from left to right: Charles Ginner, Harold Gilman, John Nash and Robert Bevan

Negative, gelatine on nitrocellulose roll film

90 x 120 mm

Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Fig.11

Alvin Langdon Coburn

The Cumberland Market Group c.1915 from left to right: Charles Ginner, Harold Gilman, John Nash and Robert Bevan

Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

In early summer 1914 Ginner became a member of Bevan’s Cumberland Market Group alongside Gilman and John Nash, which held ‘At Homes’ in Bevan’s studio overlooking the old market square (figs.10 and 11). In January 1916 he set up a painting school with Gilman at 15–16 Little Pulteney Street, Soho, where he taught Marjorie Lilly, who recalled:

No one could have looked less arty than Charles Ginner. Most people would have taken him for a bank manager, an engineer, an accountant, but never for a painter ... Only once did I see him throw off his armour of reserve completely and that was at a party, when he pushed aside a sofa to clear more floor space and executed a neat little French song and dance with complete abandon.70

The school closed in December the following year as Ginner had left for war.71 Rothenstein wrote of Ginner’s time at war:

Ginner was called up about 1916, serving first as a private in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, but his knowledge of French (he was completely bilingual) resulted in his transfer to the Intelligence Corps. He was promoted sergeant and stationed at Marseilles, and later recalled to England to work for Canadian War Records, with the honorary rank of Lieutenant.72

Working as a war artist he spent eight weeks in Hereford, close to the border with Wales, where he recorded work in a munitions powder-filling factory in a large painting, No.14 Filling Station, Hereford 1918 (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa), which has numerous sketches (for example, fig.12). Ginner served as an official war artist in both world wars.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Study for 'No.14 Filling Station, Hereford' c.1918

Oil paint on canvas

530 x 610 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.12

Charles Ginner

Study for 'No.14 Filling Station, Hereford' c.1918

Private collection

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Their partnership was a delightfully vivid and amusing affair; the austere and incorruptible passion of Gilman playing against the urbane certainty and serenity of Ginner was a spectacle much relished by their friends, and I think by themselves, for a sense of humour was their property in common.75

In 1920 Ginner had his first solo exhibition at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, with a catalogue introduction by Walter Bayes. He became a member of the New English Art Club,76 but still remained part of the avant-garde, showing in Wyndham Lewis’s Group X exhibition at the Mansard Gallery, March–April 1920. The following year he helped to organise an Exposition d’un groupe de peintres modernes at the Galerie Druet, Paris from June to July, where his work was shown alongside that of Gilman, Bevan, Nash, Stanislawa de Karlowska, E.M. O’Rourke Dickey, McKnight Kauffer, Edward Wadsworth, William Roberts and Ethelbert White.

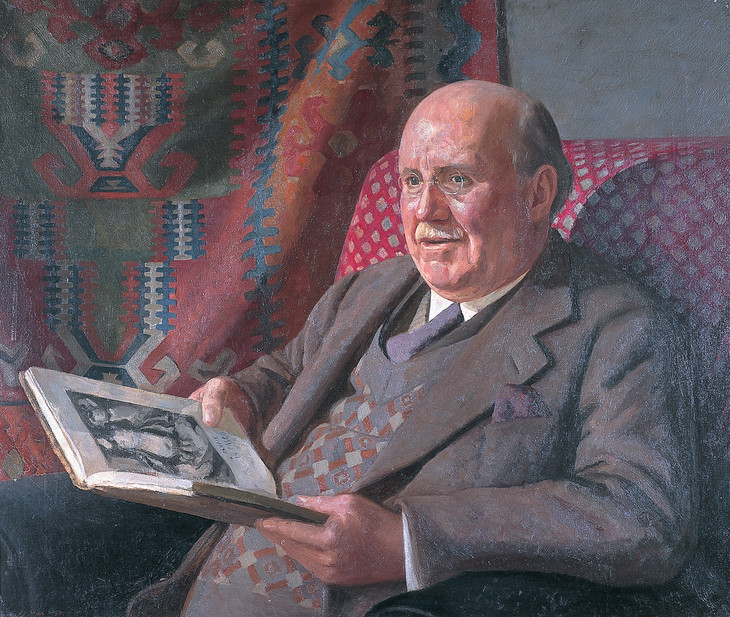

Edward Le Bas 1904–1966

Portrait of Charles Ginner 1930

Oil on canvas

Private collection

© Estate of Edward Le Bas

Photo © Janet Balmforth

Fig.13

Edward Le Bas

Portrait of Charles Ginner 1930

Private collection

© Estate of Edward Le Bas

Photo © Janet Balmforth

In 1938 he moved to 66 Claverton Street in Pimlico, close to the Tate Gallery; Snow in Pimlico 1939 (Tate N05270) is an example of the works he continued to paint from his window there. In 1942 at the age of sixty-four he was elected an Associate Royal Academician, about which he wrote to his friend and fellow artist, Stanislawa de Karlowska, ‘Last April I was elected an A.R.A.! Just imagine it, me in the Royal Academy – wonders will never cease!’80 Three years later he was also made a full member of the Royal Watercolour Society, and joked to Karlowska, ‘I am, as you see, still going up in the world.’81 In 1950 he was made a CBE for his contribution to the arts.82 Wellington’s view of Ginner in 1925 encapsulates his career:

Charles Ginner holds a special and rather enviable position among painters. Very well aware of all modern movements, ready to welcome – or to investigate with interest – any experiment, however wild, if it seems genuine and energetic, he goes on undisturbed with the exercise of his own very considerable talents. His characteristic liberality of mind finds good things among the doings of fiercely warring sects, but none of them can claim him as their own; he remains personal and independent, so that no one, I imagine, can mistake a picture by Ginner for the work of any other man.83

Ginner died of pneumonia on 6 January 1952 at the age of seventy-three. The Arts Council held a touring exhibition of forty-three of his works the following year.84

Notes

In his early pictures Ginner includes ‘I.’ as part of his signature, but he soon dropped ‘Isaac’ from his name altogether.

Ibid., p.208, and Wendy Baron, ‘Ginner, (Isaac) Charles (1878–1952)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/33410 , accessed 28 January 2011. Ruby Ginner Dyer made the final records in Ginner’s notebooks after his death, now held in the Tate Archive, TGA 9319.

Three of these illustrations are reproduced in Charles Ginner 1878–1952, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1985: Question d’Actualité 1904, Indian ink and watercolour, 195 x 280 mm (1); Du Tic Au Tac 1907, Indian ink and watercolour, 210 x 248 mm (2); and Les Suiveurs 1907, Indian ink and watercolour, 264 x 221 mm (3).

Ginner may have been encouraged to exhibit in Buenos Aires through meeting a group of wealthy Argentineans living in Paris who admired Anglada-Camarasa’s work and purportedly induced him to exhibit there from 1910. See S. Hutchinson Harris, The Art of H. Anglada-Camarasa: A Study in Modern Art, Leicester Galleries, London 1929, p.20.

Benjamin Fairfax Hall, Paintings and Drawings by Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner in the Collection of Edward Le Bas, London 1965, p.29. Wendy Baron notes that Dora was not the mistress that Fairfax Hall describes; see Baron 2003, p.518, n.15.

The work is inscribed by Ginner’s friend Anton Lock, ‘Painted in S. America. To me from C. Ginner, Anton Lock’. See Christie’s 1988 (46).

Charles Ginner, ‘Harold Gilman: An Appreciation’, in Memorial Exhibition of Works by the Late Harold Gilman, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1919, p.5.

M.S., ‘Other Exhibitions. The Camden Town Group’, Art News, 15 July 1911, p.78. The Sunlit Wall is reproduced in Baron 1979, no.84a.

The photograph, which includes Gilman standing behind Ginner, is reproduced in Easton 1970, fig.2, p.204.

Reproduced in Christie’s 1988 (122, as ‘London Bridge; Adelaide House and Fresh Wharf from the Southern End’).

Reproduced in Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008 (32).

Listed in his notebook as decorative panels entitled Chasing Monkeys, Birds and Indians and Tiger Hunting, Tate Archive TGA 9319/1. A photograph of the lost Tiger Hunting mural and an oil study are reproduced in Richard Cork, Art Beyond the Gallery in Early 20th Century England, London 1985, figs.104 and 110, pp.78 and 82–3. For more on the Cave of the Golden Calf, see Tate T00446.

Known only through reproductions in Lady’s Realm, April 1912 (as listed in Ginner’s first notebook), and the French newspaper L’Actualité, 10 November 1912; L’Actualité reproduction in Bernard Vere, ‘“The Most Wonderful and Complex City in the World”: London and the Camden Town Group’, Literary London: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Representation of London, March 2010, http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/march2010/vere.html , accessed 21 January 2011, and Jeffrey Weiss, The Popular Culture of Modern Art: Picasso, Duchamp and Avant-Gardism, New Haven 1994, p.196.

Rosalind Billingham, Artists at Applehayes: Camden Town Painters at a West Country Farm, 1909–1924, exhibition catalogue, Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry 1986, n.p.

An Exhibition of Paintings by Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner, Goupil Gallery, London, April–May 1914.

T.E. Hulme, ‘Modern Art – II. A Preface Note and Neo-Realism’, New Age, 12 February 1914, p.469. For a fuller account of Hulme’s response, see Tate T13025.

Walter Sickert, ‘Mr. Ginner’s Preface’, New Age, 30 April 1914, p.819, in Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.360.

Lucien Pissarro, letter to James Bolivar Manson, 20 November 1913, Pissarro Papers, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; quoted in Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.64.

Ibid., pp.207–8. Ginner wrote an appreciation of Gilman in Art and Letters, vol.2, no.4, Summer 1919, pp.129–35, reproduced that October in Memorial Exhibition of Works by the Late Harold Gilman, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1919, pp.3–8.

Hubert Wellington, ‘Charles Ginner’, in Exhibition of Paintings by Charles Ginner, exhibition catalogue, Godfrey Phillips Galleries, London 1925, [p.2].

Such as Flask Walk, Hampstead, on Coronation Day 1937 (Tate N05276), painted from the first-floor windows, and From a Hampstead Window 1924 (Tate N03873), painted in the attic, as well as By the Ponds, Hampstead (private collection), reproduced at http://www.bridgemanart.com .

NPG 4992. Reproduced at the National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/largerimage.php?mkey=mw02530&search=ss&firstRun=true&sText=charles+ginner&LinkID=mp01780&role=sit&rNo=0 , accessed 21 January 2011.

Charles Ginner, letter to Mrs Bevan [Stanislawa de Karlowska], 15 August 1942, Tate Archive TGA 9216/44.

Charles Ginner, letter to Mrs Bevan [Stanislawa de Karlowska], 15 July 1945, Tate Archive TGA 9216/47.

Two photographs of Ginner from this time are in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw100977/Charles-Ginner?search=ss&firstRun=true&sText=charles+ginner&LinkID=mp01780&role=sit&rNo=1 , accessed 21 January 2011.

Catalogue entries

How to cite

Helena Bonett, ‘Charles Ginner 1878–1952’, artist biography, January 2011, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www