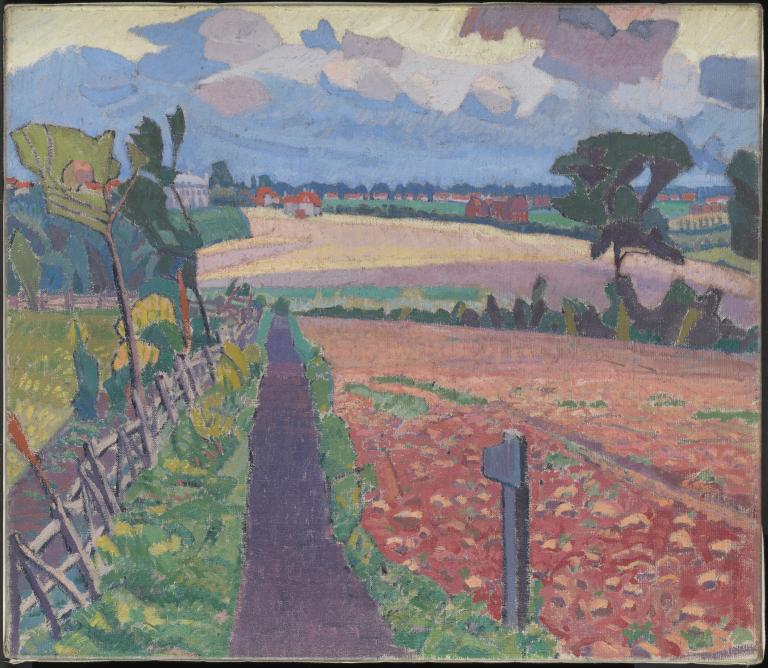

Spencer Gore The Cinder Path 1912

Spencer Gore,

The Cinder Path

1912

Gore made a number of paintings while staying with his family at Harold Gilman’s house in Letchworth, a progressive garden city north of London. The composition is anchored by a straight path leading directly away from the viewer towards the town visible on the horizon. Gore was a keen observer and accurate topographer who took an essentially naturalist approach to landscape painting.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Cinder Path

1912

Oil paint on canvas

686 x 788 mm

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1975

T01960

1912

Oil paint on canvas

686 x 788 mm

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1975

T01960

Ownership history

... ; by descent from her father to Mme Gefain, from whom bought by Frank Williams, Burford; his sale Sotheby’s, London, 22 April 1970 (303), £2,100; bought by Agnew’s for John A. Lumley, from whom bought by Tate Gallery 1975.

Exhibition history

1912–13

?Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition, Grafton Gallery, London, December 1912–January 1913 (116).

1913

?Paintings by Spencer F. Gore and Harold Gilman, Carfax Gallery, London, January 1913 (31).

1979–80

Post-Impressionism: Cross-Currents in European Painting, Royal Academy, London, November 1979–March 1980 (302, reproduced).

1997

Modern Art in Britain 1910–14, Barbican Art Gallery, London, February–May 1997 (93, reproduced).

1998–9

An Ordinary Life: Camden Town Painters, Aberdeen Art Gallery, November 1998–January 1999 (11).

2006

Spencer Gore in Letchworth, Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery, September–October 2006 (15, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (72, reproduced).

References

1974

John Woodeson, ‘Spencer Gore’, Connoisseur, vol.185, no.745, March 1974, reproduced fig.5.

1975

An Exhibition of the Bevan Gift of Paintings and Drawings by the Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Camden Arts Centre, London 1975, p.8.

1978

Tate Gallery Acquisitions 1974–1976, London 1978, pp.100–1, reproduced.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.42, 48, 292–3, 374, reproduced pl.113.

1979

Simon Wilson, British Art from Holbein to the Present Day, London 1979, p.127, reproduced p.123.

1980

Simon Watney, English Post-Impressionism, London 1980, p.121, reproduced pl.3.

1980

Wendy Baron and Malcolm Cormack, The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven 1980, p.49.

1989

Simon Wilson, Tate Gallery: An Illustrated Companion, London 1989, p.127, reproduced.

1991

Bernadette Nelson, The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1991, p.9.

1996

Robert Upstone, Spencer Gore in Richmond, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Richmond 1996, p.18.

1996

Robert Upstone, Treasures of British Art: Tate Gallery, New York and London 1996, reproduced p.225.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, pp.55, 132, 181.

2002

Ysanne Holt, ‘An Ideal Modernity: Spencer Gore at Letchworth’, in David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds.), The Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past 1880–1940, New Haven and London 2002, p.103, reproduced fig.41.

Technique and condition

The Cinder Path is painted in artists’ oil colours on primed stretched canvas. The painting appears to have been re-stretched. This was probably carried out early on or using the artist’s original materials after his death. The stretcher bears the stamp of the artists’ colourman Percy Young, from whom Gore is known to have purchased materials (see, for example, Tate T00027). The dimensions of the support do not conform to a standard commercial size, suggesting that Gore purchased and made up the stretcher separately and bought canvas from the roll, preparing the support himself. The cloth is made of hemp fibres and has a plain open weave with some uneven threads and slubs. The left-hand edge of the canvas is a selvedge with holes used to stretch the canvas on a loom for priming. The cloth has been coated with a thick glue size. This did not prevent priming from seeping through the interstices to the back. The double-white primer is evenly applied and retains the canvas weave texture. It is composed of a thin dense layer of chalk and lithopone with zinc white over a thicker more transparent layer of chalk, gypsum and zinc white. The use of lithopone in place of lead white in the upper layer seems to reflect Gore’s interest in the whiteness of his preparatory surface (see also Tate N04675). Lithopone had greater opacity and was exceptionally white, although it was known to be unstable.1 Lithopone is also found in primers on paintings of the same period by Charles Ginner and J.B. Manson.

There are marks for squaring up the canvas on all but the left-hand edge, suggesting that the primed canvas may have been squared up for transfer before stretching. The outline composition has been drawn with dark blue paint and restated during painting (see also Tate T02260). The paint has been worked to a rich, paste-like consistency and is confidently manipulated within the drawn shapes. The directional strokes often leave the white priming visible towards the borders and where a broken stroke of stiff paint has been lifted from the brush by the canvas texture. There is some reworking of the cloud forms in the sky and the field in the middle distance. In these areas, the several layers of paint required to achieve a balance of colour and form cover the priming more completely. These denser passages are enlivened by final vibrant touches of contrasting colour. The lively texture imparted by the canvas and brushwork imparts a unifying surface scatter with occasional delicately lipped impasto. The consistency of handling and surface integrates the farmed, built and natural elements depicted. The normal expectations of perspective are gently confounded by features such as the painted linear outline of the lime green tree foliage at the near left that incorporates a building located on the horizon implying that the near and distant points physically lie on the same picture plane.

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan

July 2004

Notes

How to cite

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', July 2004, in Robert Upstone, ‘The Cinder Path 1912 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Overview

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Icknield Way 1912

Oil paint on canvas

634 x 762 mm

Art Gallery of New South Wales. Purchased 1962

Fig.1

Spencer Gore

The Icknield Way 1912

Art Gallery of New South Wales. Purchased 1962

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Letchworth, The Road 1912

Oil paint on canvas

406 x 432 mm

Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery

Photo © Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery (North Hertfordshire Museum Service)

Fig.2

Spencer Gore

Letchworth, The Road 1912

Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery

Photo © Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery (North Hertfordshire Museum Service)

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Garden, Hertingfordbury 1909

Oil paint on canvas

410 x 510 mm

Fife Council Libraries & Museums: Kirkcaldy Museum & Art Gallery

Photo © Antonia Reeve

Fig.3

Spencer Gore

The Garden, Hertingfordbury 1909

Fife Council Libraries & Museums: Kirkcaldy Museum & Art Gallery

Photo © Antonia Reeve

Gore took a strictly naturalist approach to painting landscapes, and generally did not introduce artificial features. Although he sometimes treated landscape in a highly stylised manner, The Beanfield, Letchworth 1912 (Tate T01859) being a notable example, he was, in fact, generally a highly accurate topographer. In his Letchworth pictures Gore evolved a practice of rationalising the shapes of trees and clouds, giving them straight edges and outlines and a highly geometric, stylised structure. However, this was always the result of an intense study of his subject and, despite such simplification of forms, he nevertheless aimed to remain true to nature. Reviewing the exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists at the Grafton Galleries in the Art News in 1910, Gore observed that:

The attempt to separate the decorative side of painting from the naturalistic seems to me to be a mistake. Durer is supposed to have said just before he died, that he had begun to see how simple nature was. Simplification of nature necessitates an exact knowledge of the complications of the forms simplified. This may be done to produce a greater truth to nature as well as for decorative effect ... It is equally untrue to say of Pissarro, Sisly [sic], Signac, or Seurat that they cared for nothing except the momentary effects of light on objects as it is to say of Cézanne or Gauguin that they simplified objects to express the emotional significance which lies in things. All of them were equally interested in the character of the thing painted, and if the emotional significance which lies in things can be expressed in painting the way to it must lie through the outward character of the object painted.3

Elsewhere, Gore emphasised to his pupil John Doman Turner his commitment to portraying things as he found them:

Personally I always find things more interesting as they are, or if you like interesting because they are so. I am perfectly incapable of inventing the shape of a stone or how it lies on the top of another or how it would be related to everything else. I believe that it is attention to those sort of things as well as the more important which make a mans drawings more convincing than those of others who may be otherwise be his equals in skill. However some people worship one god some another and some none at all.4

Letchworth Garden City

The Cinder Path shows a point in Letchworth where town and countryside meet, the distinctively rendered and whitewashed houses with red-tiled roofs spreading out across the horizon. This mingling was a central tenet of the philosophy that lay behind the planning of Letchworth. The town’s planner, Ebenezer Howard (1850–1928), wanted to see town and country married, to create a new and better way of modern living. Howard designed Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City as self-contained satellites of London, fully provided with a range of civic amenities. The architects used were the partnership of Barry Parker (1867–1947) and Raymond Unwin (1863–1940), both influenced by William Morris’s ideals of life and labour. Houses were well designed and constructed, and cheaply priced, and the landscape and layout of the towns was carefully considered. Howard believed that a good environment and quality of life would renew and inspire the population, and ultimately lead to a better society.5 In formulating his theories he was particularly influenced by the writings of John Ruskin and William Morris, but Howard’s original, revelatory inspiration to build Letchworth came from reading the American writer Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward. Published in 1888, this novel was a fantasy about an ideal Boston in the year 2000, where capitalism had been abolished and society was now devoted to maintaining a fulfilling, mutual, egalitarian life. The novel, Howard wrote, made him realise ‘as never before, the splendid possibilities of a new civilisation based on service to the community, and not on self-interest, at present the dominant motive’.6 To develop his plans, Howard undertook a study of the industrial housing at New Lanark, Port Sunlight and Bourneville, and in 1898 published Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform.7 The first Garden City Association conference was held in 1901, hosted by George Cadbury, at which George Bernard Shaw was one of the speakers, and by 1903 Parker and Unwin had been commissioned to build Letchworth.

Letchworth was soberly and sensibly designed, and its houses generally made in a sort of comfortable, vernacular version of Arts and Crafts modern style. But from the start the new town attracted residents who were a heady mixture of high-minded socialists, militant vegetarians, teetotallers and eccentrics. The town pub, ‘The Skittles’, served only non-alcoholic drinks, while the school, built in 1905–7, had classrooms open to the elements so as to promote the healthy effects of fresh air on the lungs and encourage suitable conditions for theosophical meditation. Harold Gilman’s decision to commission a Letchworth house represents an adventurous choice, and a commitment to a progressive, new way of living, albeit one that looked to an idealised, agrarian, craft-based past. Gore’s Letchworth sojourn from August to November 1912 was perhaps simply a convenience, a move for the young family to more comfortable quarters while Gilman was absent. But nevertheless, the surroundings of Letchworth, or its palpable idealism, seem to have spurred Gore to produce his stylistically most advanced works.

There is some uncertainty as to the precise location of the scene shown in The Cinder Path. The writer John Woodeson believed it was at some point on the path that ran ‘from the end of Works Road in Letchworth (about a mile from Wilbury Road) across the fields towards Baldock, but subsequent building has altered the whole area’.8 This was certainly a route that was traditionally known locally as ‘the cinder path’, following the line of the railway; but the ridge rising to the horizon in the painting does not seem to be entirely borne out by the current topography of that part of town. Gore shows a large, Georgian-style house towards the left of the ridge that bears some resemblance to the convent that is on the Baldock edge of Letchworth, but it is natural brick rather than the grey rendering in the picture. For these reasons this location can seem to be discounted. A more likely identification is provided by Brynhild Parker, the daughter of Stanley Parker, whose parents lived next door to Gilman at 102 Wilbury Road. In 1982 she wrote to the Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery, and in recalling The Cinder Path wrote that this was the path ‘which we always took to go into town’.9 Based on Brynhild Parker’s letter, Anna Mercer, Curator of the Museum, wrote to the author that:

This cannot therefore have been the Letchworth to Baldock cinder path – I also enclose a plan of the town to illustrate this. From this you will see, however, that a direct route from Wilbury Road to the town centre would not have taken a path alongside the railway – but there is a path marked on the map, across Norton Common ... which might well have been taken. The road called Cowslip Hill, and many of the roads on this side of the town, were not built until considerably later – so going into town from Wilbury Road, would have involved crossing open fields, so there would probably have been quite a network of footpaths. There was also a footbridge across the railway more or less in line with this path, before the present bridge was built.10

Certainly a spot closer to Wilbury Road would support Gore’s usual practice of selecting landscapes that were quite close to where he was living. Whatever the precise location, in The Footpath at Letchworth 1912 (private collection)11 Gore painted a further view from the point at which the footpath in The Cinder Path turns sharply to the left. This work includes a figure walking on the path wearing a hooded blue cloak or cowl, who might be a nun or equally someone in an eccentric costume.

Technique

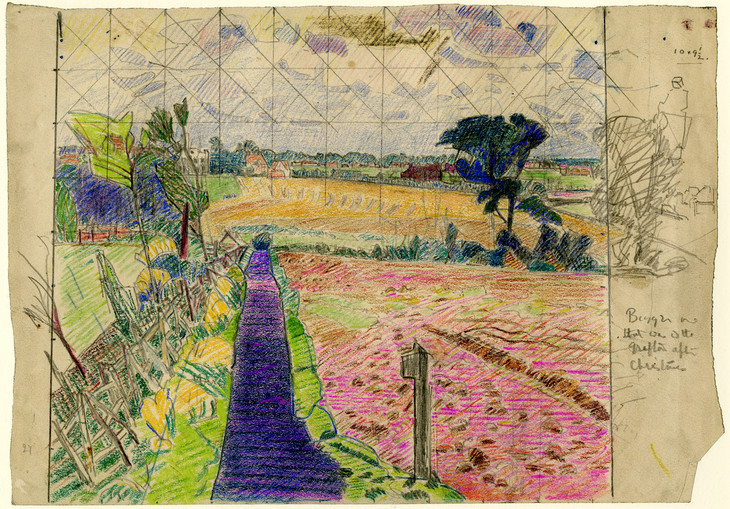

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for 'The Cinder Path' 1912

Coloured chalks and pencil on paper

235 x 332 mm

British Museum, London

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.4

Spencer Gore

Study for 'The Cinder Path' 1912

British Museum, London

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Cinder Path 1912

Oil paint on canvas

350 x 400 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.5

Spencer Gore

The Cinder Path 1912

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Gore painted The Cinder Path from a squared-up pencil and coloured chalk drawing that is now in the British Museum (fig.4). Unusually, Gore made two oil paintings of exactly the same composition; a much smaller, less finished version is in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (fig.5). It seems likely that he executed this version first, and possibly painted it on the spot. One version was shown in the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition at the Grafton Gallery from December 1912 to January 1913 (116), and the other in Paintings by Spencer F. Gore and Harold Gilman at the Carfax Gallery in January 1913 (31). Although it is difficult to be absolutely certain which version was shown where, the pencil study for The Cinder Path is inscribed in an unknown hand ‘Bigger one | that was at the | Grafton after | Christmas.’ The art historian Wendy Baron considers that it was probably the Tate painting that was included in the Grafton exhibition ‘where among radical works, its size would have been an advantage’, while the smaller Ashmolean version was placed in the more ‘intimate’ Carfax Gallery.12

This is one of the largest pictures Gore made, its scale suggesting a sense of grander ambition and importance. Its composition has an unusually high horizon, something that is emphasised by the line of red-roofed houses that stretch out across it. Such a horizon was a feature of many of Robert Bevan’s landscapes made at Applehayes in Devon (see Tate T00282). Overall, Gore’s picture is held together by the strict maintenance of harmonious colour, with a preponderance of purples, pinks and mauves. He has drawn the outlines with the brush and allowed them to remain visible. In some places the canvas has been allowed to remain bare so as to give emphasis to the outline of certain forms, such as the path, the trees and the fence. The yellow of the field in the middle distance suggests that ripe corn is growing there, while the foreground crops might be turnips or mangolds. The post in the immediate foreground is foreshortened into an oblique form, and may have had directions or a name on it.

Oddly, at the top left of the picture Gore has painted some houses on top of trees, even though spatially they are behind them, making them appear as if they are floating among the greenery. Their red roofs clash against the green, emphasising them vividly. It might be assumed to be an error, but it is a feature that appears in both versions of The Cinder Path and in the study. Possibly Gore might have been trying to resolve the way in which the buildings were visible between the leaves, perhaps as the trees moved in the wind.

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Ysanne Holt, ‘An Ideal Modernity: Spencer Gore at Letchworth’, in David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds.), The Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past 1880–1940, New Haven and London 2002, p.103.

Spencer Frederick Gore, ‘Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh &c., at the Grafton Galleries’, Art News, 15 December 1910, p.19.

Quoted in Frank Jackson, ‘The Growth and Development of the First Garden City of Letchworth’, in Where Shall I Live? The Building of the First Garden City at Letchworth (1903–14), exhibition catalogue, Nottingham University Art Gallery 1979, [p.2].

Brynhild Parker, letter to John Marjoram, Senior Curator, Letchworth Museum and Art Gallery, 17 November 1982.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Spencer Gore, ‘Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh &c., at the Grafton Galleries’ The Art News, 15 December 1910, pp.19–20.

Related film

-

Conservator Stephen Hackney on Spencer Gore's The Cinder Path 1912© 2011 Tate

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘The Cinder Path 1912 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www