Albert Rutherston 1881–1953

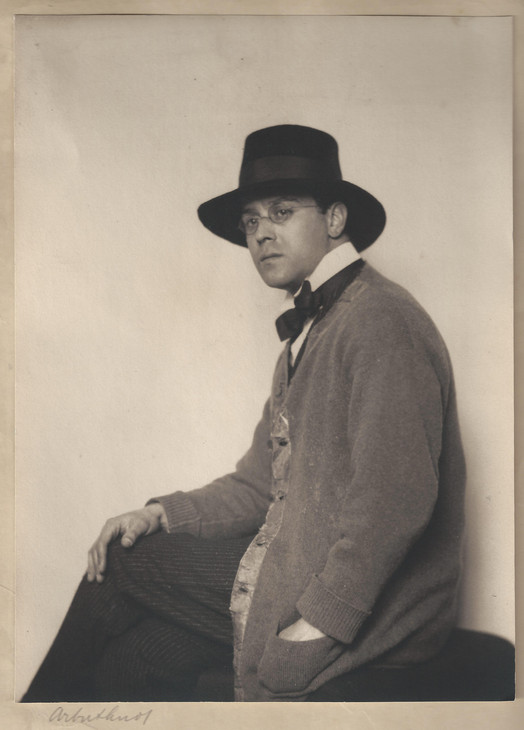

Albert Rutherston (fig.1) was a member of the talented, artistic Rothenstein family, but he anglicised his surname in 1916 during the First World War as a declaration of patriotism for the country of his birth. Born on 5 December 1881, he was the youngest of the six children of Moritz and Bertha Rothenstein, German-Jewish immigrants who had settled in Bradford in Yorkshire in the 1860s. Rutherston’s father worked in the wool cloth trade in the city and Rutherston was educated at Bradford Grammar School. His elder brother was the artist and director of the Royal College of Art, Sir William Rothenstein (1872–1945), while two of his other elder siblings, Charles Rutherston and Emily Hesslein, both accumulated impressive collections of modern British and French art. His nephew Sir John Rothenstein (1901–1992), son of William, was director of the Tate Gallery between 1938 and 1964, while William’s younger son, Michael (1908–1993), also became a distinguished artist.

Albert Rutherston 1881–1953

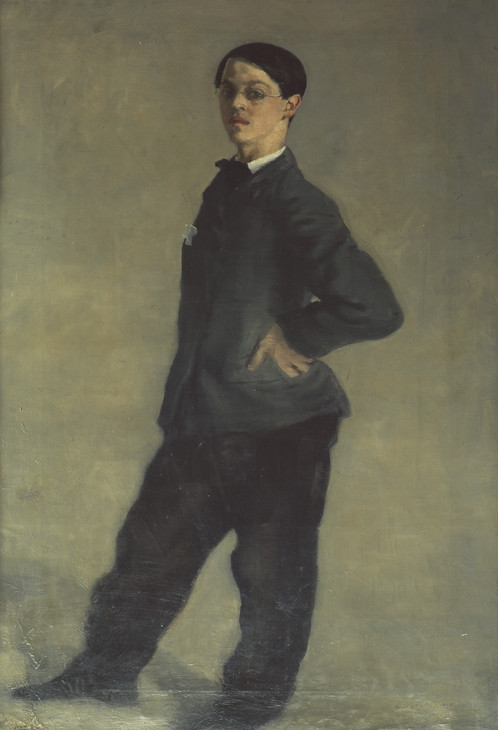

Self-Portrait at the Age of Sixteen 1898

Oil paint on canvas

955 x 655 mm

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

Courtesy of the artist's grandchildren

Photo © Ferens Art Gallery: Hull Museums

Fig.2

Albert Rutherston

Self-Portrait at the Age of Sixteen 1898

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

Courtesy of the artist's grandchildren

Photo © Ferens Art Gallery: Hull Museums

In 1898, aged only sixteen (fig.2), Rutherston moved to London to study at the Slade School of Fine Art, following in the footsteps of his elder brother. Rutherston’s time at the Slade brought him into contact with a number of the most talented artists of the day, including Ambrose McEvoy, Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman and Wyndham Lewis. His particular friends during this period, however, were the slightly senior and extremely gifted artists Augustus John and William Orpen. The trio became known as the ‘Three Musketeers’ and worked, socialised and holidayed together, indulging in what might be called typically precocious and extrovert ‘Sladey’ behaviour. In 1899 they organised a protest campaign against the installation of decorative mosaics in St Paul’s Cathedral by the Royal Academician Sir William Richmond (1842–1921). Among his contemporaries, the short-statured Rutherston was known variously as ‘Little Rothenstein’,1 ‘Little Albert’,2 or ‘All-but’.3 Although not considered an artistic prodigy like his two friends, Rutherston progressed well at the Slade. In 1900 he had two paintings admitted to the New English Art Club and in 1905 he was made a full member.

Max Beerbohm’s caricature of the New English Art Club in 1907 portrays Rutherston as a tiny, dark bespectacled figure sitting cross-legged and cross-armed underneath a table.4 This view represents his position in the British art world of the early twentieth century. He was not only physically short in stature but artistically was dwarfed by his more talented and experimental contemporaries, yet he staunchly maintained his own individuality apart from the main developments in British art. His early paintings were mostly sober interiors with figure compositions, painted with a closely observed realism reminiscent of his brother, William Rothenstein, and characteristic of the style of painting favoured by the majority of the New English Art Club at this time.

Rutherston became acquainted with Walter Sickert during a painting holiday in France in 1900, and like so many others of his generation was drawn to the older artist, later writing that, ‘I held him indeed in high hero worship; his work and personality fascinated me so much that I knew no other gateway to France than Dieppe’.5 In 1904 Rutherston engineered one of the pivotal relationships of the Camden Town Group by introducing Sickert to his friend and Slade colleague, Spencer Gore, during another painting trip. Rutherston later claimed that it was their news and enthusiasm regarding developments in the London art world which encouraged Sickert to return to England in 1905 from his self-imposed exile in Dieppe.6

In the following years Rutherston became one of Sickert’s most frequent companions and he was one of the original members of the Fitzroy Street Group, enjoying the social benefits as much as the artistic. 19 Fitzroy Street was a convenient location for the group to be based since at this time Rutherston was already living at number 18 and Gore was opposite at number 21. In a letter to his friend Ethel Sands, Sickert wrote, ‘I remember Albert used to hang out of his window in Fitzroy Street when I had the old studio here till he saw a lady ring at my bell. Five minutes afterwards he would ring the bell with the intention of dropping in.’7 Rutherston’s participation in the open studio ‘Saturday Afternoon At Homes’ only lasted until 1908 and he never became a member of the Camden Town Group. He seems to have outgrown his youthful respect and admiration for Sickert. In 1910 Rutherston wrote to his brother: ‘Of Sickert I’ve seen nothing – he’s become somehow a very tragic figure – we dined one night a long while ago & he was very delightful but he seemed a man used & worn out.’8

Rutherston was a sociable and extrovert personality who enjoyed meeting people and associating with other painters. He frequently travelled abroad in the company of other artists including Max Beerbohm, Spencer Gore and Walter Russell. He was also open to artistic experimentation under the guidance of his friends. It is therefore surprising perhaps that Rutherston’s association with the Fitzroy Street Group was so shortlived. In an article written for the Burlington Magazine in 1943, he wrote that he initially stopped attending owing to illness, and afterwards became discouraged by changes in the membership and the character of the work exhibited, so ‘I decided on a solitary path. The idea of a group of a more formal character appealed to me as little then as now.’9 The art historian Wendy Baron has suggested that the article is rather unreliable.10 Rutherston did attempt to become a member of the London Group in 1913–14 but was twice rejected, probably since by this stage his art bore no resemblance to that of his former Fitzroy Street colleagues. He had never really adopted the bright palette and post-impressionist techniques employed by other Camden Town Group artists and he had begun instead to establish a reputation for illustration and theatre design.

In 1906, while holidaying in Normandy, Rutherston was introduced to watercolour by the artist Edna Clarke Hall (Edna Waugh before her marriage in 1898). In 1910, while in Grasse on the French Riviera with the artist Gerald Chowne, he tried his hand at watercolour painting on silk, a technique most famously used by his friend, Charles Conder. From 1910 Rutherston’s work underwent a significant stylistic change reflected by the range of works on display at his first solo exhibition at the Carfax Gallery in October of that year. The majority of these were small-scale decorative watercolours, often painted on silk, featuring stylised young figures and imaginary landscapes in a highly personal linear style with thin colour washes. These works were often book illustrations, designs for stage settings and costumes, or fan-shaped panels for inclusion in pieces of furniture. An early example of his new style is the mural he executed as part of the decorative scheme for the dining room of the Borough Polytechnic in south London in 1911, now in Tate’s collection (see Tate N04569). This public art scheme was not judged a success, but other commercial commissions better suited to his talents followed, including a number of collaborations with the English dramatist and director, Harley Granville-Barker (1877–1946). In 1911 he designed costumes for Granville-Barker’s innovative production of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale performed at the Savoy Theatre in 1912. One of his last theatrical commissions before the onset of the war was to design the scenery and costumes for a new production of Le Réveil de Flore, a short ballet starring Anna Pavlova, performed in London and the United States in 1914.

The outbreak of the First World War forced a temporary halt to Rutherston’s artistic activity. A poor medical record meant that he was initially assigned a desk job working for the Engineers’ War Service Register at the Board of Trade in Westminster, but from October 1916 he served with the Northamptonshire Regiment in Egypt and Palestine. After he returned from service abroad he married an actress, Marjory Holman, in October 1919, with whom he had two sons. During the 1920s and 1930s Rutherston resumed his artistic career but was principally involved in teaching and publishing ventures. His first teaching post was at Camberwell School of Art and during the summer of 1920 he initiated a project to revitalise the Oxford School of Drawing, Painting and Design. This was eventually taken over by the Ruskin School, Oxford, where Rutherston was employed as a visiting lecturer. In 1929 he became Ruskin Master of Drawing, following the death of Sydney Carline. His own work flourished when he was recruited as an illustrator by the Curwen Press along with Claud Lovat Fraser and Paul Nash. His designs were used in a number of books including Poor Young People (1925), a collection of poems by Edith, Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell, Sitwelliana (1928), an anthology of their collected writings, and The Haggadah (1930). Rutherston also edited a series of monographs on Contemporary British Artists (1923–7) and co-wrote a publication with John Drinkwater as a tribute to their friend, Claud Lovat Fraser.

In 1938 Rutherston returned to oil painting after being introduced by Barnett Freedman (1901–1958) to a young art student, Patricia Koring. She became his model for over a decade and the portraits and nude studies which Rutherston produced of her reconfirm his considerable talent for oil painting. Rutherston continued to paint until shortly before his death, while on holiday in Switzerland, 14 July 1953, aged seventy-one.

Notes

Max Rutherston, ‘A visit to Edna Clarke Hall’, unpublished manuscript, 1989, Tate Archive TGA 921/17.

Reproduced in The New English Art Club Centenary Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1986, p.6.

Catalogue entries

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Albert Rutherston 1881–1953’, artist biography, November 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www