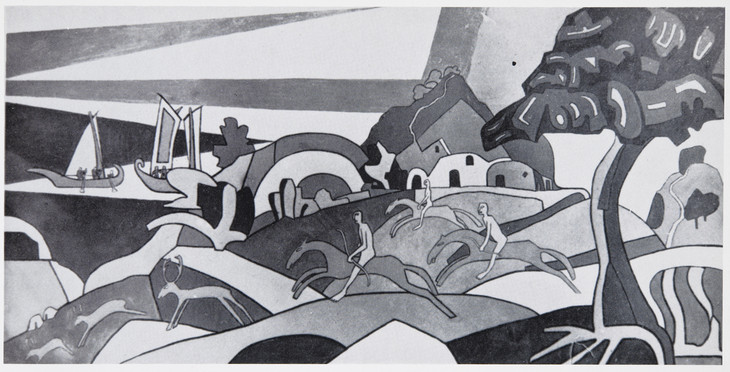

Spencer Gore Study for a Mural Decoration for 'The Cave of the Golden Calf' 1912

Spencer Gore,

Study for a Mural Decoration for 'The Cave of the Golden Calf'

1912

Frida Strindberg chose Spencer Gore to organise the bacchanalian decorative scheme of her avant-garde nightclub off Regent Street, known as The Cave of the Golden Calf. This oil study, which includes the flat forms of three orange and blue striped tigers as well as a mounted hunter and antelope, reflects the influence of Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian pictures. It is uncertain how many murals Gore completed for the club’s interior; decorations were also completed by Charles Ginner, Wyndham Lewis, Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill. The cabaret closed down in 1914; the whereabouts of Gore’s large-scale paintings, presumably executed on canvas, are unknown.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for a Mural Decoration for ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf’

1912

Oil paint and graphite on paper mounted on card

305 x 605 mm

Inscribed in unknown hand ‘S’ (?) or ‘57’ bottom right; inscribed in unknown hand ‘Decoration for ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf’ by Spencer Gore | Ginner did the opposite wall, I think. ‘The Cave of the Golden | Calf’ was a night club run by Mme Strindberg (widow of | the dramatist) circa 1912. The originals may be in the U.S.A.’ in ink on label on back.

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1961

T00446

1912

Oil paint and graphite on paper mounted on card

305 x 605 mm

Inscribed in unknown hand ‘S’ (?) or ‘57’ bottom right; inscribed in unknown hand ‘Decoration for ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf’ by Spencer Gore | Ginner did the opposite wall, I think. ‘The Cave of the Golden | Calf’ was a night club run by Mme Strindberg (widow of | the dramatist) circa 1912. The originals may be in the U.S.A.’ in ink on label on back.

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1961

T00446

Ownership history

Given by the artist in 1912 to Zina Drummond (1887–1931), first wife of Malcolm Drummond (1880–1945), from whom bought by Redfern Gallery, London, c.1930, and sold Sotheby’s, London, 12 July 1961 (242) to Tate Gallery (£90).

Exhibition history

1951

The Camden Town Group, Southampton City Art Gallery, June–July 1951 (61, as ‘Sketch for a Mural Decoration’).

1955–6

Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, (Arts Council tour), Arts Council Gallery, London, November–December 1955, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, January 1956, Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, February 1956, Southampton City Art Gallery, March 1956, Leeds City Art Gallery, April 1956, Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, December 1956 (50).

1984

The Omega Workshops: Alliance and Enmity in English Art 1911–1920, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London, January–February 1984 (40).

1985

Pound’s Artists: Ezra Pound and the Visual Arts in London, Paris and Italy, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, June–August 1985, Tate Gallery, London, September–November 1985 (no number).

1987

British Art in the 20th Century: The Modern Movement, Royal Academy, London, January–April 1987 (31, reproduced).

1997

Modern Art in Britain 1910–14, Barbican Art Gallery, London, February–May 1997 (96).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (ex-catalogue).

References

1962

Tate Gallery Report 1961–62, London 1962, p.23.

1962

‘Letters to the Editor’, Apollo, vol.76, May 1962, reproduced p.234.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, pp.249–50.

1964

Quentin Bell and S. Chaplin, ‘Ideal Home Rumpus’, Apollo, vol.80, no.32, October 1964, pp.284–91.

1976

Richard Cork, Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age, vol.1, London 1976, pp.34–7, reproduced p.35.

1976

A Terrific Thing: British Art 1910–16, exhibition catalogue, Norwich Castle Museum 1976, p.4.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.43–4, 298, 374.

1980

Simon Watney, English Post-Impressionism, London 1980, reproduced pl.90.

1980

Towards a New Art: Essays on the Background to Abstract Art 1910–20, London 1980, pp.98, 100, reproduced p.99.

1981

Charles Harrison, English Art and Modernism 1900–1939, New Haven and London 1981, p.80.

1982

Richard Cork, ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf’, Artforum, vol.21, December 1982, pp.56–68.

1985

Richard Cork, Art Beyond the Gallery in Early 20th Century England, New Haven and London 1985, pp.61–115, reproduced p.74.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, pp.50, 80 n.64, 181.

Technique and condition

Study for a Mural Decoration for ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf’ is executed in artists’ oil paints on paper. The support comprises of a single sheet of brown wove paper, which has been cut down after painting and marouflaged onto a paper-faced, wood-pulp board. After marouflage the support was again cut down on the left vertical edge, probably to frame. The support has several creases and a vertical fold running the length of the paper at the left-hand side, which appears to have been present before painting. There are several small holes and tears in the top left-hand corner that may be pin holes made to fix the paper to a board during painting, in preparation for marouflage or in working on the mural itself.

There is no preparatory sizing or priming visible on the paper support. Faint pencil marks consistent with preliminary drawing are visible in areas such as the central horse-mounted archer and the tiger. The design is initially drawn in thinned black paint (see also Tate T02260). The paint has the appearance of oil paint, where the medium has leached into the paper resulting in a consistently matt finish. The drawn shapes are boldly coloured with brushed opaque colours and substantial impasto, in some areas applied with a palette knife. The colour palette consists of blue, red, green and yellow ranging in tonality from dark to medium to light. Pure unmixed colours are quickly worked in broad directional strokes, the texture of the brushstrokes retained in the matt paint. Unpainted paper remains visible in most areas, particularly towards the edges of shapes. Some outlines are reinstated with dark blue paint, such as the tigers and goats. Existing colour is modified and further colour added over the reinstated outlines. During painting a two-inch square grid was applied in pencil, creating shallow troughs in the soft paint. Further colour and impasto were applied after the grid was drawn. High impasto has been flattened and appears more polished as a result of marouflage. The surface is unvarnished.

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan

September 2004

How to cite

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', September 2004, in Robert Upstone, ‘Study for a Mural Decoration for ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf’ 1912 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

The Cabaret Theatre Club, later known as The Cave of the Golden Calf, was a nightclub at 9 Heddon Street W1, off Regent Street. It was the brainchild of Frida Strindberg (1872–1943), the divorced second wife of the Swedish dramatist August Strindberg (1849–1912), and opened on 26 June 1912. Strindberg was an Austrian who had inherited a large fortune at an early age, and worked variously as a translator, journalist and author; she was described by the journalist Ashley Gibson, who met her shortly before the club opened, as

an amazingly masterful, intelligent, and in her way fascinating Austrian ... She already gave proofs of a mesmeric faculty for getting people to do things for her, and showed a rare discrimination in her choice of accomplices. Instinct led her without fail to select the young men who mattered, or were going to.1

Much more famously she was described by Augustus John, with whom she was infatuated, as ‘the walking hell-bitch of the Western World’.2 Jacob Epstein recalled that the project to open the club was launched at a dinner for ‘artists and those she thought would be interested in her scheme’; it should have sounded a warning for all those involved:

The meal was sumptuous, the champagne lavish. When the management presented the bill Madame Strindberg took it in her hand, and turning to the company said: ‘Who will be my knight, tonight? ... There was no response from the company!’3

Strindberg chose Spencer Gore to organise the club’s decorative scheme, which was intended to reflect and contribute to its intended avant-garde status. In a preliminary brochure issued in April 1912, Strindberg stressed that the club’s ‘decoration will be entirely and exclusively the work of leading young British artists’.4 Gore was the coordinator, and commissioned others of his circle to contribute works. The project took up much of his time during this period, and it appears also to have sapped his emotional strength, for he suffered constant pressure and unnecessary interference from his patron. Generally an even-tempered man, Gore admitted his uncharacteristic annoyance in an undated letter to his pupil John Doman Turner:

I have been stopped by the cabaret decorations which have taken up a lot of time that I regret[.] days and days I have spent arguing about the colour of the walls and ceiling. Most irritating thing I ever had to do with.5

Gore’s mention of wall and ceiling colours indicates that he was not just responsible for organising the specific fine-art decorations for the club, but also its overall design. He involved Charles Ginner, who painted three large wall decorations, Chasing Monkeys (untraced), Birds and Indians (untraced) and the triptych Tiger Hunting (untraced, fig.1),6 as well as designing two posters for the club in distemper (see, for example, fig.2).7 Wyndham Lewis was a friend of Strindberg, and it may have been through him that Gore gained the commission. Lewis painted a drop curtain depicting raw meat for the stage, and he also hired out his painting Kermesse (untraced),8 which hung on the stairs down to the club. Epstein carved coloured and decorated columns and capitals, most likely pursuing a sexual theme,9 while Eric Gill was commissioned to make a phallic-looking statue of a Golden Calf for the foyer.10 He also designed the sign outside, a relief version of the calf sculpture flanked by flaccid penises.11

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Tiger-hunting mural in the Cave of the Golden Calf 1912 Central panel of triptych

Distemper on canvas

Approximately 183 x 183 cm

Whereabouts unknown

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.1

Charles Ginner

Tiger-hunting mural in the Cave of the Golden Calf 1912 Central panel of triptych

Whereabouts unknown

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo courtesy of the Gore family

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Poster in distemper

c.213 x 137 cm

Whereabouts unknown

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo courtesy of Jeffrey Weiss

Fig.2

Charles Ginner

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Whereabouts unknown

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo courtesy of Jeffrey Weiss

The name of the club was intended to convey a message of primitive abandon through its reference to the Biblical story of the Israelites who, while Moses was absent, indulged in orgiastic, idolatrous celebrations before a golden calf (Exodus 32: 1–6). The brochure for the club reinforced this bacchanalian agenda:

Our aims have the simplicity of a need. We want a place given up to gaiety, to a gaiety stimulating thought rather than crushing it. We want a gaiety that does not have to count with midnight. We want surroundings, which after the reality of daily life, reveal the reality of the unreal.12

Gore had problems trying to coordinate the other artists’ work, and it progressed very slowly, with Strindberg constantly urging them to be ready by the planned opening. Lewis would only work if absolutely forced, with Gore’s wife standing over him, and when the club opened his drop curtain was still wet and got snarled up. Ginner worked almost equally slowly, starting late in the morning and taking long lunch breaks, a practice Gore attributed to his residence in France. Gore himself worked hard and long, a habit he had maintained throughout his career.13 Mollie Gore helped her husband with his work, and ‘primed the canvas, melted the size, mixed the paint and began to fill in the colours’.14

Designs

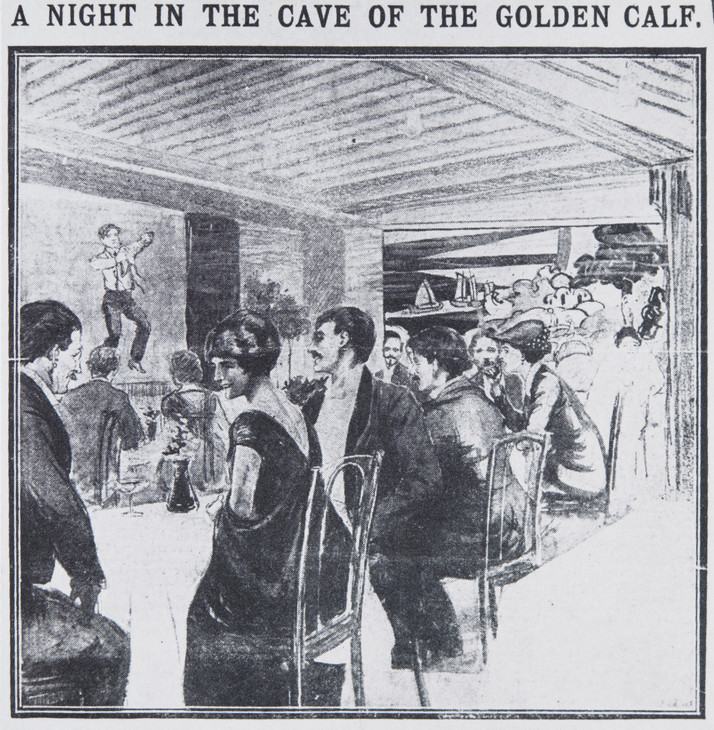

Several sheets of studies for Gore’s designs survive, and these indicate that initially the artist was planning to decorate a large number of the interior walls.15 As it turned out, he appears to have given much of this work to Ginner. It is difficult to be certain of the precise number of decorations Gore actually executed. The mural Deer Hunting (untraced, fig.3) was certainly completed, as it is shown in an illustration of the club in the Daily Mirror on 4 July 1912 (fig.4), situated on the wall to the right of the stage. The Tate’s oil study has a trio of orange and blue-striped tigers in it, and might have been the subject taken over by Ginner and represented by his triptych Tiger Hunting. However, the man on horseback is shooting an arrow at a deer or antelope, and so this could equally suggest that the design was an alternative for Gore’s mural Deer Hunting. There are a number of references that suggest Gore executed further finished murals. Strindberg writes of ‘your pictures’ in a letter to him in 1913,16 and Lewis too, in his obituary of Gore, referred to his ‘large paintings’ for the commission.17

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Deer-hunting mural in the Cave of the Golden Calf 1912

Distemper on canvas

Dimensions unknown

Whereabouts unknown

Photo courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.3

Spencer Gore

Deer-hunting mural in the Cave of the Golden Calf 1912

Whereabouts unknown

Photo courtesy of the Gore family

A Night in the Cave of the Golden Calf 4 July 1912 in The Daily Mirror

Fig.4

A Night in the Cave of the Golden Calf 4 July 1912 in The Daily Mirror

In a letter of February 1962 to the Tate Gallery, Gore’s widow recalled the circumstances of her husband’s work on the project. By implication, she suggested that there was just a single design by her husband, and explained how the Tate study was presented to Zina Drummond:

My husband and Ginner each did a separate wall & Wyndham Lewis did the drop curtain ... Lewis had a studio large enough to take his drop curtain, but Ginner & my husband had to hire a studio with clear wall space large enough for two decorations, and they kept every one out until they were nearly finished – Then one Fitzroy Street day they said I could take any of the members to see the decorations & it was then that they presented the sketches to the two members’ wives present – Mrs Robert Bevan who got the Ginner & Mrs Drummond, Zena, his first wife, she died, got the Gore. That’s how it was.18

The Tate study is in the same simplified, vibrantly coloured manner as Gore’s other studies for the project, and in both subject and style is clearly influenced by Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian pictures. Gore had seen a group of Gauguin’s works at the Stafford Gallery in November 1911,19 and commemorated the exhibition and his excitement in his painting, Gauguins and Connoisseurs at the Stafford Gallery 1911 (fig.5). The subject matter of wild beasts and tribal hunters must have been chosen deliberately to emphasise the carefree and hedonistic ideals of the club. Tribal societies, often dubbed as ‘primitive’, were a cipher for a simpler way of life that was more in tune with human needs and emotions, and in particular, the erotic urge. This fantasy of what tribal life in somewhere like Gauguin’s Tahiti might be like was partly a reaction against the mechanised, industrialised, urban, alienating society that early modern Britain had become, and also a response to the continuing restrictiveness of accepted sexual morals. That the club had a popular image of sexual freedom is testified by its citation in a sensational divorce trial in July 1914, and description as an unsuitable place for a respectable married woman to visit.20

The club was a venue for drinking, eating and, most notably, watching an extremely varied programme of performances. The Times reported that:

Austin Harrison,21 Spencer Gore, and Leon Daviel, acting as a preliminary committee, write that the first English Artists’ Cabaret will be opened ... The club will open at 8.30 each evening, and from 9 o’clock till 11.30 a varied programme will be given. On the opening night there will be dances from Goya’s ‘Caprichos’, morris and hieratic dances, and a scene from a Breton ‘Wake’ of quite Hogarthian character. Spanish gipsies will sing their old mysterious lore – a feature entirely new to any English stage. The reigns of Charles II and the Georges will supply each their particular quota of mirth and song. The more serious note will be struck in works by Bantock, Delius, Lapara, Fried, Mistral, Moret and in the form of modern English poetry drama and satire.22

The opening night performances included songs by the Norwegian singer Bokken Larsson,

a description of the club by a mythical ‘Cook’s Man’, piano jests by Mr. Dalhousie Young, cabaret songs by M. Rienzi and M. Percy, two barefoot dances by Miss Margaret Morris, Indian musicians and much else.23

The club mixed the avant-garde with more obscure or arcane material from the past in its bills. A performance of Pergolese’s La Serva Padrona attracted a long review in the Times which, as well as drawing attention to the ‘Futurist paintings’, praised the Club’s ‘catholicity of outlook’.24

The position of the club below street level probably gave rise to the ‘Cave’ part of its name; possibly the ‘prehistoric’ associations suggested by cave dwelling influenced Gore’s choice of savage scenes. The art critic of the Observer was quick to compliment

this group of artistic revolutionaries upon the happy title which has been bestowed upon and accepted by them. The ‘Troglodytes’, or ‘Cave-dwellers’, is a singularly appropriate appellation for a coterie of artists, who are not only connected with the ‘Cave of the Calf’, but who aim – most of them – at the primitive simplicity of the days when art was in its infancy. It was, after all, on bones and on the walls of caves, that the artistic instinct found its first expression.25

The club was seen as a distinctly continental phenomenon by the Times which, while sceptical of its success, praised its creativity:

The Cabaret has not sprung up naturally in the soil of London, and therefore it appears hazardous to transplant it thither. On the Continent it is traditional for men of letters and of art to have their café, but in England one fancies it is the old-fashioned club or nothing ... In London, too ... there is the music-hall, perhaps nowhere else so dangerous a competitor to the cabaret.

For these reasons the prospect that the Cabaret Theatre Club will become a social centre remains for the present highly speculative; it seems on the whole more probable that its chief success will be found to lie in its dramatic activity, for it will have rare opportunities to produce works of theatrical and musical virtuosity, and has already announced a d’Annunzio tragedy and a Pergolese opera.

The club house is dubbed ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf,’ and it is certainly cavernous to the extent that it has to be entered by a sort of man-hole; within there is a small stage and mural decorations representing we should not care to say what precise stage beyond impressionism – they would easily, however, turn into appalling goblins after a little too much supper in the cave.26

For these reasons the prospect that the Cabaret Theatre Club will become a social centre remains for the present highly speculative; it seems on the whole more probable that its chief success will be found to lie in its dramatic activity, for it will have rare opportunities to produce works of theatrical and musical virtuosity, and has already announced a d’Annunzio tragedy and a Pergolese opera.

The club house is dubbed ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf,’ and it is certainly cavernous to the extent that it has to be entered by a sort of man-hole; within there is a small stage and mural decorations representing we should not care to say what precise stage beyond impressionism – they would easily, however, turn into appalling goblins after a little too much supper in the cave.26

The club was viewed as a triumphal achievement for Gore by his contemporaries, and this success led to him being invited by the Daily Mail to make decorative designs for a modernist house in the Ideal Home Exhibition. But Gore decided to pass on the commission, and this led to a row between Lewis and the Omega Workshops who both believed they had been given it.27

In his obituary of Gore, Lewis highlighted the club decorations as among Gore’s best work, and asked that ‘the memorial exhibition of his work shortly to be held should, if possible, since the Cabaret Club has closed, contain the large paintings he did for that place’.28 The memorial exhibition never took place, cancelled in the wake of the outbreak of war in August 1914. A grieving Walter Sickert viewed the club differently, blaming the hard work and interminable wranglings as contributing to his friend’s death. ‘I wished he hadn’t had that long fatiguing rotten period of running that blasted cabaret’, he wrote to Nan Hudson.29 ‘I tried all I could to prevent his hacking himself to pieces with that bloody Madame Strindberg’s Cabaret. That was a mistake’, he wrote later the same month to Ethel Sands.30

The club had been a great critical and popular success, but by 1914 it was in financial difficulties and Strindberg seems never to have paid the artists involved the fees they had been promised. On 14 April 1913 she wrote characteristically to Gore:

I quite understand that you and Ginner will not wait any longer for the money, but what can I do? The only proposition is that I make over to you my property, 4 oil paintings, 5 drawings, 30 etchings by Augustus John, which represents the sum of £535 that I owe you and something more to cover interest. The pictures are mortgaged at present, but I shall have them back soon and if you will be satisfied with this transaction we can include it in some more work to be done.31

This arrangement naturally enough seems to have fallen through, and in 1914 Strindberg closed the club and sailed to the United States, leaving behind her a wake of creditors, and apparently taking many of the decorations, including Gore’s murals. Mollie Gore’s description of her husband and Ginner hiring a studio to execute the works and Lewis’s call for them to be included in a memorial exhibition confirms that they were made on canvas or some other transportable support, rather than being painted directly on the walls of the club, and so the removal by Strindberg seems certainly to have been physically possible. Attempts to trace these and other works from the club have, however, reaped no indication of their whereabouts at any time after they were displayed in the Cave of the Golden Calf.

Ownership

The first owner of the Tate study was Zina Drummond (née Ogilvie), first wife of the artist Malcolm Drummond, whom she married in 1906. She was a painter and illustrator, and was drawn by Sickert in c.1913–14.32 A label on the back of the picture is inscribed in ink in an unknown hand ‘Decoration for ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf’ by Spencer Gore | Ginner did the opposite wall, I think. ‘The Cave of the Golden | Calf’ was a night club run by Mme Strindberg (widow of | the dramatist) circa 1912. The originals may be in the U.S.A.’33

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Ashley Gibson, Postscript to Adventure, London 1930, p.103; quoted in Richard Cork, Art Beyond the Gallery in Early 20th Century England, New Haven and London 1985, p.67.

Quoted in Michael Holroyd, Augustus John: A Biography, London 1976, p.480; for a full account of her life, see Monica Strauss, Cruel Banquet: The Life and Loves of Frida Strindberg, New York and London 2000.

Reproduced in ‘Un Cabaret de cubistes à Londres’, L’Actualité, 10 November 1912. Reproduction is from Jeffrey Weiss, The Popular Culture of Modern Art: Picasso, Duchamp and Avant-Gardism, New Haven 1994, p.196.

A study for Kermesse is reproduced in Cork 1985, p.89; the work itself is untraced and not reproduced.

Frederick Gore, ‘Spencer Gore: A Memoir by his Son’, in Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1974, p.12.

Austin Harrison edited English Review (1910–23) and in 1905 became editor of the Manchester Guardian. It seems possible that he was a relation of Gore and Bevan’s patron Harold Bertram Harrison (1855–1924); see Tate T00282.

See Quentin Bell and S. Chaplin, ‘Ideal Home Rumpus’, Apollo, vol.80, no.32, October 1964, pp.284–91.

Related biographies

Related essays

- Leisure Interiors in the Work of the Camden Town Group Jonathan Black, Fiona Fisher and Penny Sparke

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Wyndham Lewis, ‘Frederick Spencer Gore’ BLAST, No.1, June 1914, p.150.

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Study for a Mural Decoration for ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf’ 1912 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www