Spencer Gore The Gas Cooker 1913

Spencer Gore,

The Gas Cooker

1913

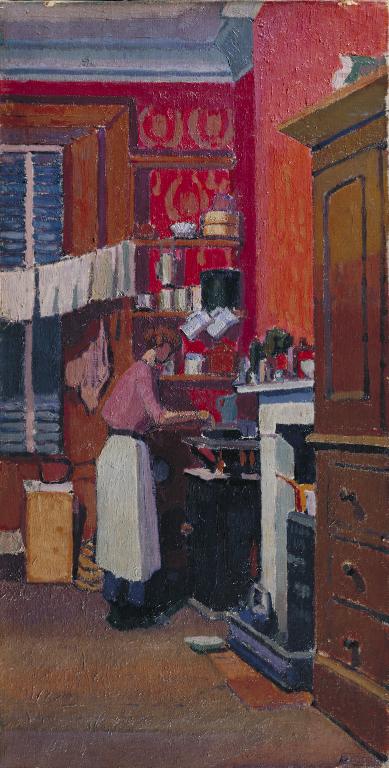

Gore’s wife Mollie is shown cooking over the gas stove in their flat at 2 Houghton Place, NW1. The painting’s strong verticals emphasise the height of the ceiling in their quarters, located on the first floor of a five-storey house once occupied by a single family. Crimson wallpaper with a gold laurel wreath pattern indicates the kitchen’s previous function as a drawing room. Lowered blinds suggest the time of day to be evening; the family’s laundry hangs near the window from a line secured to shelving stacked with plates and pots.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Gas Cooker

1913

Oil paint on canvas

710 x 370 mm

Inscribed by Harold Gilman ‘Painted by S.F. Gore at 2 houghton Place [...] the Gas Cooker. Painted from a drawing without any painted study [...] is his [...] to represent gas light. Painted in the year 1913. Unsigned 173(a)’ on label on back; studio stamp ‘S.F. GORE’ bottom right.

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1962

T00496

1913

Oil paint on canvas

710 x 370 mm

Inscribed by Harold Gilman ‘Painted by S.F. Gore at 2 houghton Place [...] the Gas Cooker. Painted from a drawing without any painted study [...] is his [...] to represent gas light. Painted in the year 1913. Unsigned 173(a)’ on label on back; studio stamp ‘S.F. GORE’ bottom right.

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1962

T00496

Ownership history

Mrs Mary Johanna Gore, the artist’s widow, from whom bought through Redfern Gallery, London, for £650 by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest and presented to Tate Gallery 1962.

Exhibition history

1913–14

Exhibition of the Work of English Post Impressionists, Cubists and Others, Public Art Galleries, Brighton, December 1913–January 1914 (53).

1916

Paintings by the Late Spencer F. Gore, Carfax Gallery, London, February 1916 (36, 50 guineas).

1928

Exhibition of Paintings by Spencer F. Gore, Leicester Galleries, London, April 1928 (43).

1955–6

Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, (Arts Council tour), Arts Council Gallery, London, November–December 1955, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, January 1956, Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, February 1956, Southampton City Art Gallery, March 1956, Leeds City Art Gallery, April 1956, Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, December 1956 (40).

1962

Spencer Gore and Frederick Gore, Redfern Gallery, London, February–March 1962 (64, reproduced).

1970

Spencer Gore 1878–1914, The Minories, Colchester, March–April 1970, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, April 1970, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, May–June 1970 (61, reproduced on front cover).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, February–May 2008 (46, reproduced).

References

1962

Sunday Times, 6 May 1962, p.13, reproduced.

1962

Tate Gallery Report 1961–62, London 1962, p.24.

1962

John Rothenstein, The Tate Gallery, London 1962, reproduced p.253.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, p.250.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, p.375.

1992

Maureen Connett, Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group, Newton Abbott 1992, pp.40–1, reproduced p.37.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.182.

Technique and condition

The Gas Cooker is painted on primed stretched canvas. One of Harold Gilman’s handwritten paper labels is attached to the back of the stretcher (see also Tate T02260), inscribed: ‘Painted by S.F. Gore at 2 houghton Place [...] the Gas Cooker. Painted from a drawing without any painted study [...] is his [...] to represent gas light. Painted in the year 1913. Unsigned 173(a)’.1 The cloth is plain, relatively close-weave linen. The cut edges of the canvas are uneven and the lines marking up for cutting are still visible in places (see also Tate N05099). The canvas is stamped at the back in the centre with the mark of artists’ colourman P. Shea. Its stretched dimensions also conform to a standard commercial size, suggesting it was purchased pre-stretched. Sizing has been applied to the cloth, which is visible as a minimal layer on the canvas, and double white priming containing lithopone in the upper layer. Primer has been evenly applied and conforms to the canvas weave texture. The preparation is consistent with Gore’s choice of materials (see also Tate T01960).

The painting has been squared up in a black graphic medium to transfer the design from a drawing. Initial drawing in dark blue paint on the primed canvas is still visible at the edges of some forms (see also Tate T02260). The painting is confident in execution and no visible changes have been made to the composition of the subject during painting. Opaque colour was applied within the confines of each shape, in a fairly medium-rich malleable paint, which has formed soft ridges at the edges of forms. Layers of paint were built up as the colour of the shapes was modified, applying fresh paint when the layer below was touch-dry. Earlier campaigns are left visible at the edges of the shapes, revealing in some areas the process of modifying colour values through several layers (see also Tate T01859). In the final stages, touches of paint have been applied wet-in-wet to describe detail and add accents of colour, and contours are reinstated with the same blue used for the initial drawing.

Gore probably used artists’ oil paint direct from the tube. A good range of pre-mixed colours were available from artists’ colourmen at this time. The tube paint would have been applied directly onto a palette and mixed as required. Among those that Gore used, a large, elongated palette has survived, rather like a traditional portrait painter’s palette. The artist probably laid it on a flat surface while he worked. The dried colours preserved on the palette are consistent with those seen and identified on Gore’s paintings: relatively pure spectral colours, with no evidence of mixing with earth colours and no black (see also Tate N05099). White has been used directly from the palette, by picking it up with a brush loaded with coloured tube paint and applying the lightened tone straight onto his canvas. Zinc white was also identified as an admixture in some colours; if used by Gore, it may be an early use by a British artist, again reflecting the influence of contemporary French painting technique.

Roy Perry, Joyce Townsend and Sarah Morgan

July 2004

Notes

How to cite

Roy Perry, Joyce Townsend and Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', July 2004, in Robert Upstone, ‘The Gas Cooker 1913 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Spencer Gore shows the kitchen at 2 Houghton Place, NW1, with his wife Mollie cooking at the gas stove. The writer John Woodeson stated that:

Mrs S. Gore informed me that she did not formally pose for the picture, but that Gore made sketches of her while she was working in the kitchen. The room is the kitchen of the Gore’s flat at 2 Houghton Place, and double doors lead to the front room.1

Three pencil studies for the painting are in private collections: one shows just the figure of Mrs Gore (356 x 254 mm), another the kitchen without any occupant (355 x 240 mm, Agnew’s, London), but the third is a graphite and blue pencil version of the oil painting’s full composition (354 x 258 mm), the only difference being that in this third drawing Gore has included the detail of their cat Bunty drinking a saucer of milk, a feature absent in the final design. None of these drawings are squared up; a squared-up watercolour for the final composition, presumably that upon which Gore based the Tate painting, was sold at Sotheby’s.2 It differs from the final painting only in that it shows Mollie standing more upright, rather than slightly bending over the stove.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

In Sickert’s House at Neuville 1907

Oil paint on canvas

587 x 457 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.1

Harold Gilman

In Sickert’s House at Neuville 1907

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Gore showed this painting in the Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others he organised at Brighton Public Art Galleries that opened on 16 December 1913. A label on the back of the stretcher written by Harold Gilman states: ‘Painted by S.F. Gore at 2 houghton Place [...] the Gas Cooker. Painted from a drawing without any painted study [...] is his [...] to represent gas light. Painted in the year 1913. Unsigned 173(a)’.3 Gilman’s reference to Gore attempting to capture the effect of gas lighting is interesting. This is evidently an evening scene, something also suggested by the window’s lowered blind. There is, however, little in the picture that implies a type of light that is distinctive to gaslight, although Gore does emphasise the warm rich colours of the red wallpaper and its harmony with the browns of the floor and cupboards and Mollie’s blouse.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

The Kitchen c.1908–9

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 458 mm

National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

Photo © National Museum of Wales

Fig.2

Harold Gilman

The Kitchen c.1908–9

National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

Photo © National Museum of Wales

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Shopping List 1912

Oil paint on canvas

615 x 510 mm

British Council

Photo © Rodney Todd-White & Son

Fig.3

Harold Gilman

Shopping List 1912

British Council

Photo © Rodney Todd-White & Son

It might be supposed that gas stoves were unusual when Gore painted this in 1913, but in fact they had become quite common and technically modern in their design. The sort of gas stove at which Mollie stands, apparently cooking something in a frying pan, was extremely common and was produced in large numbers. Like a modern stove, it had an oven below and a ring with gas jets above.4 Until about 1880 gas had been relatively expensive, the preserve of more affluent households, and gas companies were not interested in providing gas to working class houses. The invention of the pre-payment gas meter in the 1880s transformed the potential of gas supply and made it commercially viable for mass consumption, both for lighting and cooking. The meter meant that the company was paid for its gas in advance, something they considered an important feature if gas was to be piped into working class houses. They also offered simple appliances such as gas rings, small cookers and lights on hire purchase or rental agreements which proved an effective way of selling more gas. Cooking with gas seemed in some sense to represent a modern world, as well as having a number of practical advantages. N.R. de Lissa noted in a guide devoted to using the new stoves published in 1913:

To use gas for cooking means, in effect, a saving of labour, time, temper, prevents dirt and mess, and it keeps the house cool and free of cooking odours in summer ... Never let the flame appear outside the saucepan but extend simply under the entire bottom surface. Any excess of gas beyond this is simple waste ... It is a well-recognised fact that gas companies and stove makers do not like to hear of gas used extravagantly, as this, although it may swell a quarter’s account will never arrive at encouraging the use of the finest domestic medium for obtaining heat for cooking that has ever been known to the present day.5

The Houghton Place kitchen also has an older range in the fireplace, presumably coal-fired, on which sits a copper saucepan, and in the hearth is a kettle. The kitchen has a string of washing across the window, presumably to catch the breeze when the window was open, a symptom both of not having enough space or perhaps access to the garden, and also a young baby. Foodstuffs crowd along the mantelpiece and tins and pans are stacked on the open shelves. The Gores occupied an interesting social position. They were living in relatively modest accommodation, in an area that once had been more affluent. Formerly occupied in their entirety by single families, the large houses were now divided into flats. When Charles Booth (1840–1916) walked the area with Police Inspector Wait on 28 October 1898 for his survey of London poverty, he recorded in his notebook, ‘East into Harrington Sq and south down Houghton Place into Ampthill Sq: “The whole of this district” said Wait “is on the decline: lodgers are coming in more and more”’.6 In his Maps Descriptive of London Poverty (1898–9), Booth colour-coded Houghton Place as a mixture of red – indicating the second most affluent level in his system of categorisation and described as ‘Middle class. Well-to-do’ – and purple, which was two steps lower and which he described as ‘Mixed. Some comfortable others poor.’ Presumably the Gore’s only had income derived from picture sales, but nevertheless they employed a cleaner, the sitter in Tate’s North London Girl (Tate T00027).7

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Modern British & Irish Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, Sotheby’s, London, 28 September 1994 (56, reproduced).

N.R. de Lissa, Cooking by Gas: A Guide to the Correct and Economical Use of the Gas Cooking Stove, London 1913, pp.29, 28.

Related biographies

Related essays

- City Visions: The Urban Scene in Camden Town Group and Ashcan School Painting David Peters Corbett

- Her Indoors: Women Artists and Depictions of the Domestic Interior Nicola Moorby

- From Drawing Room to Scullery: Reading the Domestic Interior in the Paintings of Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group Juliet Kinchin

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘The Gas Cooker 1913 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www