Fig.1

John Constable

The Cornfield 1826

National Gallery, London

Much has been written about John Constable’s success at the Paris Salon of 1824, but his participation in the next Salon of 1827–8 has received far less attention. This relative neglect is perhaps not so surprising, given that the single painting he exhibited, The Cornfield 1826 (fig.1), did not repeat his earlier triumph. The same Salon at which Constable met with a critical setback, however, also marked the debut of Paul Huet, the artist usually regarded as his closest French follower. But if critics and artists seem out of step in their attitudes to the English artist in the later 1820s, the real flowering of Huet’s engagement with Constable has often been overlooked, since it came more than a quarter of a century later.

Fig.2

Paul Huet

The Flood at Saint-Cloud exhibited 1855

L’Inondation à Saint-Cloud

Louvre Museum, Paris

Fig.3

John Constable

The Hay Wain 1821

National Gallery, London

This paper is in two parts. The first looks at the circumstances in which The Cornfield was presented in Paris and offers a close consideration of its critical reception. Under the direction of the painter and antiquary the Comte de Forbin, who had been such a staunch advocate for Constable in 1824, the Salon of 1827 helped to consolidate the position of the new French Romantic painters, while landscape painting also gained greater prominence. In marked contrast to his standing in 1824, however, Constable’s work was placed in a marginal position and, although largely disregarded by critics, was treated with outright hostility by the few who mentioned it. At the same time, the Salon was said to be full of his imitators. The negative terms in which certain critics now accounted for Constable’s work underlines just how short-lived and narrowly focused this phase of enthusiasm for Constable was in France, but it also indicates the extent to which artists and critics seemed to be at cross purposes. The second part of this article takes up the case of Paul Huet, whose early work has been central to any discussion of the Anglo-French landscape connection. The focus here, however, is on one of his most ambitious later pictures, The Flood at Saint-Cloud (L’Inondation à Saint-Cloud) exhibited 1855 (fig.2), in which memories of Constable’s The Hay Wain 1821 (fig.3), which was exhibited at the Salon of 1824, were drawn upon and reworked.

The discussion is framed by the watery terms of ‘marsh’ and ‘flood’. The first refers to the pointed French word marécages (marsh) which Étienne-Jean Delécluze, in his critical commentary on the Salon of 1827, chose to describe the pictures Constable had exhibited at his first Salon. The second refers to the subject of Huet’s picture, which although it depicts a situation Constable himself never painted, sets up a significant dialogue with the English master.

The Cornfield at the Salon of 1827

Fig.4

John Constable

View on the Stour near Dedham 1822

Huntington Art Museum, San Marino, California

There would have been every reason for Constable to have high expectations of the Salon of 1827. The two large pictures he had shown at the previous Salon, The Hay Wain and View on the Stour near Dedham 1822 (fig.4), had attracted widespread attention and even come close to acquisition by the French state.1 Both had found purchasers in France and the celebrity he had so unexpectedly found abroad had resulted in further commissions. At the close of the Salon he had been awarded a gold medal – as the art historian and curator Patrick Noon has observed, this was ‘probably the vindication of a life’s struggle’.2 True, in 1827 he could no longer depend on the services of his French dealer John Arrowsmith, who had gone out of business in the interim. Claude Schroth, the other Paris-based dealer who had invested in his work, had also scaled back his enterprise, and though he had offered his assistance should the artist wish to send anything to the next exhibition, in the end Constable sought the help of the London dealer Dominic Colnaghi to make arrangements on his behalf.3

The key figure Constable needed to cultivate was the Comte de Forbin, Director General of the Royal Museums, who had prime responsibility for the conduct of the Salon. He had been a member of the jury in 1824 and had been instrumental in ensuring a favourable position for Constable’s two principal pictures. Forbin had at first assumed that they would be seen to best advantage at a distance, but as Constable related to his friend John Fisher, Forbin realised that their quality lay in ‘the richness of the texture and the attention to surface of objects in these pictures, a thing unknown in their own paintings’, and had them repositioned in a place of honour in the Salon Carré so they could be appreciated at closer quarters.4 It was Forbin who conveyed to Constable by letter the formal notification of his gold medal, adding that he had taken pleasure in drawing the attention of King Charles X to Constable’s work.5 Forbin had also been among the first to admire, at Schroth’s gallery on the Rue de la Paix in March 1825, Constable’s two new paintings of Hampstead Heath commissioned by the dealer.6 To smooth the way for his return to the Salon, taking advantage of a visit to Paris by Colnaghi in September 1827, Constable sent the Count a gift of a small landscape painting, accompanied by a diplomatic letter.7

Even more than the Salon of 1824, that of 1827 was marked by the contest between the old guard of the classical tradition and the emergent Romantics, but this time, despite forming a minority of the exhibitors, it was the latter who gained the advantage. In her detailed study of the exhibition, art historian Eva Bouillo makes it clear that the establishment of the new aesthetic at the heart of the French art world was largely due to the strategic role played by Forbin. She shows how he was able to lend his support to the Romantics, independently of the authority of the vicomte Sosthène de la Rochefoucauld, super-intendant of the Beaux Arts and to whom Forbin was nominally answerable. This he achieved through strategic placement of significant works and by judicious use of the system of rewards and commissions.8 In marked contrast to the Salon of 1824, English artists were a more marginal presence in 1827 and Constable, whatever his hopes may have been from his previous connections with Forbin, found himself at no particular advantage.9 His contribution to the Salon played no part in what turned out to be an almost exclusively French triumph.

Constable would have originally expected the next Salon to be held in 1826, since it had been a bi-annual event. Thanks to the promotion of Arrowsmith and Schroth, his reputation had been strong in Paris through 1825 and that year he was also invited to contribute to a Salon in Lille; he sent two pictures, including The White Horse 1819 (Frick Collection, New York), borrowed from Fisher, and was awarded a second gold medal.10 There were surely good grounds for hoping that his official success in France would continue in 1826. The Salon was delayed until the following year, however, mainly for financial reasons, and its opening pushed back to the autumn.11 He chose to send The Cornfield, which he had already shown twice in London without finding a buyer; it appeared in the Salon booklet as Paysage aux animaux (Countryside with Animals).12 The delay to the Salon must have hurt his chances of success, and by the time his picture eventually went on display, the critical tide had already turned against him.

The arrangement and hanging of the Salon had presented Forbin with an even more intractable problem than usual this year, and again revealed the unsuitability of the Palais du Louvre as a venue for such events. On top of the usual drawbacks associated with the cumbersome apparatus of state patronage, he now had to find a way of dealing with the accumulated backlog of two and a half years of artistic production.13 The Salon would eventually go through three distinct arrangement of rooms (‘parcours’) and four different arrangements of exhibits. According to Bouillo’s research, Constable’s painting only made its appearance at the third of these, after 6 February 1828.14 This is confirmed by the fact that there are no reviews mentioning the picture before February. Although Delécluze noted that Constable was among the exhibitors in an article dated 5 November 1827, the day after the exhibition first opened, this was presumably on the basis of the catalogue only.15

It was not necessarily a disadvantage to have a major work put on display only at this later stage of the Salon; Eugène Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalus 1827 (Louvre Museum, Paris) was introduced at the same time and it still emerged as one of the most discussed paintings of the whole event. Besides, this third hanging represented the exhibition’s fullest and most characteristic phase, in which Forbin’s strategy was most evident. The first two hangs had been widely criticised for the confusing sequence of the spaces and the scattered, incoherent nature of the display.16 More to the point was the peripheral position allocated to Constable’s picture. It was hung in the easternmost wing of the Louvre, in the galleries adjacent to the great colonnade of the east façade of the palace. This was about as far removed from the Salon Carré as it could have been.17 The contrast with 1824, as far as the spectator’s encounter with Constable was concerned, can hardly have been greater. The Salon Carré, traditionally regarded as the most prestigious location and the scene of his former triumph, had not been available for Forbin’s first arrangement of the galleries in November 1827. It had been re-instated for the second hanging, and in the third especially was exploited by the count to display some of the most dramatic, and in some cases contentious, works by Charles-Émile Champmartin, Delacroix, Achille Devéria, Théodore Gudin, Ary Scheffer, Xavier Sigalon and others. The front line of the new movement had shifted decisively to history painting and was now presented as a purely French concern.

Bouillo compiled tables charting the exhibits most frequently cited by the critics in the extensive coverage of the Salon of 1827, but there is no mention of The Cornfield among the 116 paintings she lists. While the critical indifference to Constable’s painting has been generally noted in the literature, it was in fact singled out by some critics, but only to be dismissed in the most emphatic terms.

The critic of Le Figaro was the first mention him: ‘We noticed in passing some Constable landscapes painted with a carelessness and a heavy-handedness never previously demonstrated by the painter’.18 The remark might itself be thought somewhat careless since Constable was represented by only one landscape, but a striking contrast is made here between his new picture and his previous exhibits. In a later bulletin, Le Figaro returned to the theme, looking back to how the artist had first been perceived:

It is perhaps to a foreigner, who since then seems to have come to a halt in the middle of the very path he had successfully opened up, it is to Constable that we owe the first attempts at a kind of painting which, with its harsh truths, came as something of a shock to eyes transfixed by a conventional view of nature, but which already demonstrated a meticulous attention to all the chance effects of landscape. A great number of our artists have walked in the Englishman’s footsteps and we can be justly proud of the reputations of many of these today.19

In the view of this critic, Constable had already been outpaced by the French landscape painters he had so recently inspired.

Another critic, Auguste Jal, also took the line that Constable had failed to live up to the expectations raised in 1824:

Three years ago, two paintings by Constable and two portraits by Lawrence were worthy of our praise; but this year the courteousness of the jury has been pushed too far. Adopting a harsh attitude to French artists, the judges displayed considerable indulgence towards the London artists: the injustice is doubly regrettable. The Constable painting exhibited under no.219, is worse than mediocre and with all the familiar defects of its creator, has neither the naivety nor the colouring which, in 1824, drew such admiration for the work of the leading English landscape painter. It is a trivial nature, lacking any kind of charm, a systematically crude execution and, lastly, a mass of colours devoid of brilliance and without truth.20

Jal’s uncompromisingly hostile verdict on Constable’s painting can be read as part of his broader polemic against the institution of the Salon jury itself, but given how few English artists actually participated in this Salon, his insinuations of favouritism on the part of the jury seem unjust, bordering on the xenophobic.

Delécluze did not think much of the picture either, although this is not so surprising, given his consistent advocacy of the paysage historique, in which landscape could be elevated by reference to subjects from history, mythology or literature, and his conviction that the landscape artist must abstract from nature and idealise his subject matter:

A number of English landscape painters have submitted work for our Exhibition. This year, Mr Constable’s contribution was weak; but we were delighted by two Views of Venice painted by Mr Bonington. These paintings are indeed remarkable. Nor shall we forget the highly original depiction of the long avenue leading to Windsor Castle painted by Mr Daniell.21

Yet Delécluze had formerly shown himself aware of the shortcomings of the nascent French landscape school and had been prepared to allow that Constable had, at first, a valuable lesson to teach. He was, moreover, not indifferent to the qualities of English scenery, having spent six months in England in 1826 – in his memoirs, he recalled the ‘the charming and original landscapes of that island’.22 His favourable mention of William Daniell’s The Long Walk at Windsor c.1826 (whereabouts unknown) is interesting; as it happens, he had made a sketch of the very same subject himself only the previous year.23

Had Constable simply chosen to send the wrong picture to Paris? Had he sent The Leaping Horse 1825 (Royal Academy, London) instead, would it have been regarded as a worthy successor to The Hay Wain, enabling him to hold on to his reputation as the artist at the forefront of the new landscape painting?24 At the time of writing, it so happens that The Hay Wain and The Cornfield are displayed side by side at the National Gallery in London. The contrast is instructive, though of course no spectator in Constable’s time could have had the luxury of this direct comparison. There are marked differences in the character of the two works, as has frequently been remarked, but it could be argued that, if anything, many of the qualities that make The Cornfield distinctive ought to have made it eminently suitable as a Salon submission. In The Cornfield, the prospect is more conventionally framed, there is a higher degree of finish and definition in the detail, the handling is vigorous and emphatic, the scheme of tone and colour built up around the contrast of silver clouds and golden corn. So how to account for the assertions of negligence, heaviness, weakness and mediocrity made by French critics in 1828?

It is true that The Cornfield has sometimes been regarded as something of an exception among Constable’s works. This is partly due to the ‘eye salve’ the artist claimed to have added, giving it a higher degree of finish in the hope of making a sale.25 Art historian Michael Rosenthal, for example, has interpreted the painting as a falling back from the naturalism and integrity of the six-footers that preceded it.26 The English critics had been altogether more generous in their reviews of the painting when it was shown at the Royal Academy in 1826 and again at the British Institution in the spring of 1827, and there was certainly no suggestion of any decline in the artist’s competence.27 In France, though, the initial enthusiasm turned quickly to indifference and disdain, but the comments made by critics of the Salon on The Cornfield are insufficiently nuanced to enable us to identify specific issues they may have had with the picture. We are left only with the claim that Constable now had nothing more to offer French landscapists, but given the relatively short duration of exposure to his work, the idea that his example had been absorbed so completely might be regarded with legitimate scepticism.

Delécluze dismissed The Cornfield with the single word, ‘weak’, but in a piece on the Salon in the Journal des Debats three weeks earlier he recalled the positive effect of Constable’s presence at the Salon of 1824: ‘[Constable’s paintings] did at least have a positive effect on our French landscape painters in that they forced them to recognise the extent to which their own use of colour was heavy, dull and contrived’.28 It is the phrase that follows, however, that is particularly striking: ‘Mr Constable’s marshes [marécages] were also in vogue; he was imitated then and is still imitated now’.

The last part of the sentence has become familiar enough. It was quoted by R.B. Beckett, for example, in his commentary on Constable’s correspondence with Arrowsmith and Schroth.29 But it is the use of the word ‘marécages’ that compels attention here – it is such an unlikely term to apply to the The Hay Wain and The View on the Stour near Dedham. We have become accustomed to thinking of the Suffolk represented in Constable’s pictures as a place of improved and productive land, of carefully managed water regimes and navigable rivers. Moreover, this would have been clear from the titles given in the Salon catalogue: a hay wain crossing a ford below a farm; a canal in England.30

Given the circumstances, we can take Delécluze’s marécages figuratively, as referring to the uncertain ground onto which the English painter was tempting young French artists, luring them away from the Italian ideal, the classical tradition and the paysage historique.31 It is a further expression of his idea of the antithesis between north and south that had informed the extended study trips Delécluze himself had recently made, to Italy in 1823–4 and England in 1826, in order to test his principles and confirm the validity of his beliefs. There is a detectable sarcasm in that word marécages, but behind the sense it conveys of a waterlogged country, an unstable region of saturation and flux, lies a wider set of assumptions about the link between climate and artistic achievement. In the previous century, ideas on the influence of climate had been associated with the writings of Jean Baptiste Dubos, Montesquieu and Johann Joachim Winkelmann, and had traditionally privileged Italy, and more recently Greece, as environments most propitious for excellence in the arts.32 Delécluze could hardly have chosen a more inappropriate word to describe the paintings that Constable had actually exhibited, but it serves to point up the risk impressionable young landscape painters were running of getting bogged down in unprofitable northern wetlands. His comment, though, seems to anticipate the surface water that glints in so many of the paintings by Théodore Rousseau and other artists associated with the Barbizon school.33

For Jal, Constable’s failure with The Cornfield signalled the end of a regrettable episode:

The English school was to lose all the importance it had gained three years earlier, to the delight of some and the distress of others. ‘Look’, one landscape painter commented, ‘Constable is really bad this time. Never mind – so much the better really! Defeated today, the English will not dare to show their faces in 1829; they won’t steal our medals and our public acclaim’. Yet it was thanks to them that you embarked on new paths.34

Landscape painting, in his view, was now safely in the hands of French artists. Delécluze, on the other hand, as we have seen, warned of the continuation of Constable’s influence: ’He was imitated then and is still imitated now’.35 But what did it mean to be a follower of Constable in 1828 and after? Contact with his most significant work had been relatively limited. True, the View on the Stour near Dedham and The Hay Wain had remained in France. Both eventually entered notable private collections in Paris: that of Louis-Joseph-Auguste Coutan in the Place Vendôme in the first case; and of Boursault-Malherbe in Pigalle in the second.36 Boursault was a prominent figure – he had variously been an actor, playwright, theatrical entrepreneur, politician, businessman and horticulturalist – and as art historian Linda Whiteley has pointed out, he also had a family connection with Delacroix.37 Whiteley has speculated that the Boursault circle – ‘a little romantic inner circle’, as she calls it – might be the channel by which the influence of The Hay Wain was ultimately transmitted and consolidated:

It is not unreasonable to suppose that this environment which would have seemed utterly incongruous to Constable himself, nevertheless encouraged a generation of younger artists to look closely at this painting, and enabled more solid and substantial links to be made between the events of the 1824 Salon and the landscape painting of Théodore Rousseau and his contemporaries.38

This fascinating suggestion touches on what we might take to be the holy grail of the study of Anglo-French artistic relations – the search for the Constable-Rousseau connection.39 It remains a speculation, however, and in the present state of our knowledge it is difficult to be sure exactly how ‘the landscape painters of 1830’ could build on the English example.40 Certainly The Cornfield did nothing to bridge the gap between 1824 and 1830. At any rate, those hostile to the new landscape in 1827 were certain that there were no real principles involved, merely a ‘kind of madness’, nothing but an indulgence in overwrought conventions.41

Paul Huet and The Flood at Saint-Cloud

Huet made his debut at the Salon of 1827 with a Vue des environs de La Fère (View of the Area Around La Fère) (now lost), entirely overlooked by critics in a year in which landscape was gaining prominence: Bouillo estimated that thirty per cent of the exhibited paintings and lithographs were of landscape subjects.42 The growing popularity of the genre reflected the development of tourism to the French provinces and an increasing sense of the distinctiveness of regional character, as well as a retreat from the conventions of ideal landscape, evident in the emphasis on specific locations, atmospheric conditions and times of day. Within a few years, however, Huet had emerged as a leading figure in this new landscape school. His testimony as to Constable’s impact has often been quoted:

The two paintings by Constable were remarkable particularly on account of their effortless originality, underpinned by truth and verve. Exhibited in 1824, this was perhaps the first time that their freshness could be sensed, the first glimpse of that luxuriant and verdant nature with no trace of darkness, no coarseness or manner. A cottage, half-hidden in the shade of magnificent trees, a clear stream and a ford crossed by a horse and cart and, in the distance, the London countryside, suffused in the moist English air.43

Huet’s comments come from the notes he prepared for the critic Theophile Silvestre in 1854, recalling his impressions thirty years after the event. Silvestre’s request for information must have prompted him to reflect on his own career and perhaps helped him to define his place in relation to a new phase of landscape painting closely associated with Barbizon. But it cannot be a coincidence that this retrospective survey is also accompanied by a resurgence of an engagement with Constable in Huet’s own work. This appeared as if to re-assert the influence of the English master on the course of Romantic landscape in France, at a time when Romanticism itself was challenged by a new realist aesthetic. The Flood at Saint-Cloud might be regarded as the great set piece of this highly personal Constable revival.

Fig.5

Paul Huet

Caretaker’s Cottage in the Forest of Compiègne 1826

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

Fig.6

Paul Huet

View of Rouen from Mont aux Malades 1831

Vue générale de Rouen prise du Mont-aux-Malades

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, Rouen

Scholars seeking to trace the influence of Constable in the formation of Huet’s landscape practice have, logically enough, concentrated on the period of the immediate aftermath of the Salon of 1824 through to the early 1830s. The Caretaker’s Cottage in the Forest of Compiègne (fig.5), a large canvas dated 1826 but not exhibited in the artist’s lifetime, has been cited as the exemplary immediately post-Constable picture. Although mixing in elements from Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1521), as Patrick Noon has shown, it contains an unmistakeable echo of Willy Lott’s house in The Hay Wain, that ‘cottage, half hidden in the shade of magnificent trees’, as Huet would later remember it.44 Noon has pointed to other plausible candidates too, but it is Huet’s ambitious View of Rouen from Mont aux Malades 1831, shown at the Salon of 1833, that is now generally acknowledged as the climax of this early phase (fig.6).45 The identity of many of the paintings by Constable that had entered France as a result of the initiatives of Arrowsmith and Schroth, and their subsequent whereabouts (and therefore accessibility), remains difficult to establish with any certainty. With time and the increasing circulation of dubious copies and pastiches, the situation becomes still murkier, to say nothing of variations based loosely on prints.46 But the View of Rouen, an extensive vista of open slopes, rutted tracks and big skies, with no framing device at either side to edit down or narrow the prospect, has an evident relationship with the two views of Hampstead Heath commissioned from Constable by Schroth in 1825; they had remained in his possession, for his own pleasure, even after he had withdrawn from dealing in paintings.47

More than thirty years later, in one of the most significant paintings of his career, and one destined for the particularly prestigious context of the 1855 Exposition Universelle, Huet returned to his early source of inspiration. The reference to The Hay Wain in his The Flood at Saint-Cloud is explicit enough, although it has been mostly overlooked, and the connection does not seem to have been made in the extensive coverage by contemporary critics of the 1855 exhibition.48 But to read Huet’s canvas in terms of Constable’s influence is to go against the grain of what quickly emerged as a dominant, more pessimistic interpretation. The Flood can only be fully understood as a multi-layered painting, drawing on several traditions in order to forge a grand synthesis of older masters and modern art.

The more usual response has tended to emphasise its darker, even catastrophic, qualities, stemming ultimately from its perceived relationship with Winter (The Deluge) 1660–4 by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), but coloured also by Huet’s own reputation as a painter of the unleashed powers of nature.49 It is hardly surprising that these darker readings should have made the allusion to the noonday high summer pastoral of The Hay Wain more difficult to perceive. Furthermore, the idea of Constable as one of the founding influences on French landscape has itself been vigorously contested by Huet’s son and biographer René Paul Huet. In his book, René Paul was at pains to minimise Constable’s role in the shaping of his father’s sensibility, invoking support from Huet’s contemporary the critic Gustave Planche, as well as from later French writers on art.50 He mentions The Hay Wain and The Flood at Saint-Cloud in the same sentence, but only in order to express his scepticism about the extent of the influence of the English master.51 All the same, he published in full the notes on Huet’s first encounter with Constable as quoted above, which his father made for Silvestre. This account is the source for the information that Huet made a small copy of The Hay Wain on that occasion.

How is The Hay Wain echoed in The Flood? Most obviously, there is the motif of the horse-drawn cart standing in shallow water, a two-wheeled cart with high open sides in this case, harnessed to a single horse, with two other horses standing by (Constable had shown a heavier-duty vehicle, a timber wagon temporarily modified for transporting hay).52 The two paintings have a comparable spatial structure: both have a stretch of shallow water in the foreground with the main river flowing beyond, revealed just above the cart in Constable’s picture and by a break in the screen of trees in Huet’s. Although more evident in an early oil sketch such as The Mill Stream. Verso: Night Scene with Bridge c.1810 (Tate), and the mezzotint of the same title published in English Landscape Scenery, the opening to the river in The Hay Wain is admittedly easily missed, or rather easily mis-read.53 Someone not familiar with the location itself could hardly be expected to realise that we are looking through to a navigable river. Thanks to the research of local historian Attfield Brooks and others, we now see the advantage of a detailed knowledge of the water system at Flatford, the arrangement of main stream and backwaters, dams, locks and ponds, whereas for Huet the painting could not have been tied to a specific topography, as his comment on ‘the London countryside’ referred to earlier, makes clear.54

Above all, both paintings are depictions of modern rural life, presented on a large scale. Despite the reactions of contemporary reviewers – Théophile Gautier spoke of its ‘strange and desolate aspect’, for example, while Maxime Du Camp commended ‘a well-captured sinister atmosphere’, going on to note ‘a passing boat, ferrying wretched people hints at the terrible drama we sense rather than see’ – there is nothing portentous going on in the foreground of Huet’s picture.55 It is a scene of salvage: the figures in the boat and cart are retrieving floating casks, and perhaps driftwood. The Seine’s floods are seasonal, temporarily disruptive no doubt, but ultimately beneficial. All the same, France was a flood-prone nation and there were many years in which the flooding of major rivers had devastating consequences.56 Indeed, there is a strand of contemporary French paintings which dealt with just such episodes. Jean-Pierre Alexandre Antigna had shown his large canvas of The Flood of the Loire (L’Inondation de la Loire) (now lost) at the Salon of 1852, and the following year Gustave Brion exhibited The Potato Crop During the Flooding of the Rhine Flood in 1852 (La Récolte des pommes de terre pendant l’inondation du Rhine en 1852) (Musée d’Arts de Nantes, Nantes); both focused on the plight of local inhabitants.57 The year after Huet’s painting was exhibited, south and central France was affected by the worst flooding of the century, particularly in the Saône and Rhone Valleys, and paintings were commissioned by the State designed to draw attention to the beneficence and humanity of the Emperor Napoleon III. These included William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s Napoleon III Visiting the Victims of Tarascon in June 1856 (Napoleon III visitant les victims de Tarascon en Juin 1856) exhibited 1857 (Hôtel de Ville, Tarascon) and Hippolyte Lazerge’s His Majesty the Emperor Distributing Aid to Flood Victims in Lyon (Sa Majesté l’empereur distribuant des secours aux inondés de Lyon) 1856 (Musée Nationale du Château de Compiègne, Compiègne).58 These are exercises in modern history painting, not landscape, and Huet’s The Flood at Saint-Cloud is in a very different mode. For all its stormy spectacle and the eerie effect of light, it is essentially bound to quotidian experience, secured to that world by the memory of Constable’s canal and river scenes, and the artist’s own deep familiarity with the moods and fluctuations of the Seine.

Huet’s view is taken from river level somewhere near the famous cascade below the Château of Saint-Cloud, and shows the great sweep of the Seine looking upstream to the Pont de Sèvres, barely recognisable in these flood conditions since the water level comes so close to the tops of the arches. This was a stretch of river he knew intimately and had represented on many previous occasions. In his youth, he had spent his summers on the Île Séguin, immediately above the Pont de Sèvres, as a guest of the family of his friend and fellow artist Charles Lelièvre, who had a house there. In that period the island was relatively wild: in his etching The Flood on the Île Seguin (L’inondation dans L’île Seguin) 1833, Huet’s earliest-known flood subject, he renders the site dense and impenetrable as a rain forest.59 He told Silvestre that the island was the place that made him a landscape painter, and indeed he has sometimes been referred to as ‘a pupil of the Île Séguin’.60 René-Paul Huet maintained that the idea for what would become The Flood at Saint-Cloud originated on this island before he first encountered Constable’s work in 1824, another small point in support of his case against the formative influence of the English artist. Huet’s obsessive return to his first place of inspiration is striking in itself, however, and suggests a parallel with Constable’s own career.

This was a landscape of personal associations, but the resonance of Huet’s painting is also partly due to the historical significance of the location. The château had been built by Philippe, Duc d’Orléans, brother of Louis XIV, and the gardens and park were laid out in rivalry to those of nearby Versailles; the most impressive feature was the great cascade descending from the terraces adjacent to the palace to the level of the river, surmounted by allegorical figures of the Seine and Marne. In the early nineteenth century, the château and its domain had become a popular destination, both for Parisians and foreign tourists. J.M.W. Turner was particularly attracted to it, devoting no less than three subjects to Saint-Cloud in the second volume of his Annual Tour on the Seine.61 Turner preferred to keep to the high ground above the river, commanding extensive views towards Paris. Huet in contrast turns away from the grand siècle, the great period of the reign of Louis XIV, and the palace’s more recent associations with the Imperial court and modern leisure. He looks instead towards the vernacular world and to the spectacle of the Seine unbound, moving through the great trees at the margin of the park, elemental forces temporarily prevailing over those of culture and artifice. In this respect, Huet’s painting moves up through registers not found in Constable’s canal scenes.

Fig.7

Nicolas Poussin

Winter (The Deluge) 1660–4

Louvre Museum, Paris

Gautier, taking up the idea of a noble architecture submerged, likened the trunks of the trees to the columns of a cathedral, and then went on to evoke, as Du Camp had done, ‘flat boats gliding silently through the water loaded with indistinct figures like shades crossing the river Styx’.62 Admittedly, this sombre note was sounded in the context of his tribute to Huet written on his death in January 1869. In that context it is entirely appropriate that Gautier should have chosen to allude to another of the references clearly made in the painting, that to Poussin’s Winter (fig.7), from the series The Four Seasons. The painting depicts the flood from the Bible’s Old Testament, and was more often referred to as The Deluge; it shows the imminent extinction of human life on earth, and was also known to be the last painting Poussin ever created. The painting had come to be highly regarded in the early years of the nineteenth century – echoes of it are to be found in the work of Anne-Louis Girodet, Géricault and Turner, among others, and in alluding to it, Huet was following an illustrious Romantic tradition.63

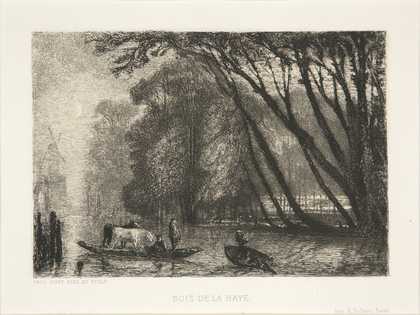

Fig.8

Paul Huet

Etching of Le Bois de la Haye 1864–5, executed 1867

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

Fig.9

John Constable

The White Horse 1819

Frick Collection, New York

Evidence to support the claim that reference to Constable was a self-conscious component of The Flood at Saint-Cloud comes just over a decade later with Le Bois de la Haye (Setting Sun in an Autumn Fog) Le Bois de la Haye (soleil couchant par un brouillard d’automne) 1864–5 (Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Orléans, Orléans), exhibited at the Salon of 1866 and purchased by the state for the museum at Orléans. An etching of the work (fig.8) was published in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1867.64 The subject is another flood scene, this time set in the Netherlands (which Huet had visited in 1864), and there are good reasons to identify it with the painting Huet told his friend Auguste Petit he wanted to make as a pendant to The Flood.65 The two paintings are comparable in composition and mood, with screens of tall trees and a deep space opening beyond, landscapes transformed by inundation. But what is particularly striking here is the motif of the white horse being ferried across the water, an unmistakeable allusion to Constable’s The White Horse (fig.9), the painting the latter had sent for exhibition in Lille in 1825 and for which he won his second gold medal. It is possible that Huet may have travelled to Lille to see it – given his enthusiasm for Constable at that period, it is not inconceivable.66 But in any case he had had the opportunity to see The White Horse at the International Exhibition in London in 1862, as discussed in the postscript below.

Another indication of a mid-1850s revival of interest in Constable comes with the appearance of an article on the artist by artist and art historian Frédéric Villot in the Revue Universelle des Arts in January 1857.67 The piece took the form of a review of the second edition of C.R. Leslie’s Memoirs of the Life of John Constable, which had been published in London almost twelve years earlier.68 Drawing on Leslie’s transcriptions of Constable’s correspondence with Fisher and William Brockedon, Villot revisited the heady days of 1824, when Constable appeared as ‘a messiah of landscape’, bringing a vital stimulus to the regeneration of French landscape painting.69 Villot, at that time keeper of painting at the Louvre and, like Huet himself, a close friend of Delacroix, regretted that Leslie’s biography was not known in France:

The memoir published by Mr Leslie very much deserves to be translated and is the only work to adequately convey the true value of the English artist. We have Cellini’s memoirs, along with those of Bernard Palissy: it is to be hoped that we will soon have those of Constable.70

In the event it would be nearly another fifty years before Leslie’s book was published in French, translated by the writer Léon Bazalgette and prefaced with an essay on ‘Constable et les paysagistes de 1830’.71

At the Salon of 1869, a few months after his death, Huet was represented by a large charcoal sketch for The Flood at Saint-Cloud.72 It had evidently been submitted as a tribute to his late father by René-Paul, perhaps underscoring the melancholy aspect of the subject for the occasion, along with two of Huet’s paintings and two of his own. It makes for an intriguing epilogue to the original. The size is not identical to that of the canvas exhibited in 1855, but it is unusually large (1300 x 1620 mm, compared to 2035 x 3000 mm for the painting), and of course the medium is different too. But the echo of Constable’s practice of making full-scale studies for his big exhibition pictures is suggestive enough to raise the question as to whether he had heard something of the English master’s unique methods.

Fig.10

Théodore Géricault

The Raft of the Medusa 1819

Le Radeau de la Méduse

Louvre Museum, Paris

Huet’s The Flood at Saint-Cloud was eventually purchased by the state in 1857, partly as a result of Delacroix’s advocacy. It was sent to the Musée de Luxembourg in Paris, giving it the highest profile of any of his works, and was widely acknowledged as his masterpiece.73 After Huet’s death, the historian Jules Michelet was to claim that Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (fig.10) was ‘very close to The Flood at Saint-Cloud’. This revealing comment ties Huet’s painting to that great breakthrough in Romantic art in France, and ascribes to the vision of a practitioner of landscape, as art historian Chiara O’Reilly has noted, something of the grandeur of modern history painting itself.74 The link with Géricault is especially fitting, since it was he who initiated the whole process by which Constable’s work was introduced to France: it was his enthusiasm for The Hay Wain at the Royal Academy in 1821 that led to Arrowsmith’s interest in the artist and the presentation of the picture at the Salon of 1824, leading to Huet’s enthusiasm for it in turn. Michelet emphasised the darker, tragic, more elemental aspect of Huet’s vision in bringing out the connection with Géricault’s Medusa, but from another perspective we can see the aftermath of The Hay Wain working through his Flood just as clearly.

Postscript: full circle

In 1862 both The Hay Wain and The Flood at Saint-Cloud were brought together for the International Exhibition in London: Huet’s picture had been chosen by the French selection committee charged with putting together a survey of the last ten years of art in France, while The Hay Wain was lent by George Young, who had owned the painting since at least 1853.75 The White Horse was also among the paintings by Constable on display. At the same time, Henry Vaughan lent the full-scale sketch for The Hay Wain to the Sheepshanks Gallery, then known as the National Gallery of British Art and adjacent to the site of the International Exhibition in South Kensington.

Huet had heard that his painting had been well-placed and judged ‘a true success’ by several people. In July he travelled to England to see for himself, and there, according to René-Paul’s account, ‘he rekindled all the enthusiasm of his youthful response to the Ford [The Hay Wain]’.76 René-Paul also notes that his father made a second sketch of The Hay Wain, larger than the one he had done back in 1824: ‘On his return from London … he produced a larger version based on a rough sketch made in front of the painting and then transformed into a wash drawing when he got back to his hotel that evening’.77 We have no record of what other pictures he saw while he was in London. He could perhaps have renewed his acquaintance with The Cornfield, at that time also on display in South Kensington, though in the light of its reception in Paris in 1828, he may have had no incentive.

Huet took the opportunity to travel in the English landscape itself, however, as detailed in letters to his wife and daughter. He compared the Long Walk at Windsor with the parc de Saint-Cloud, and visited Stonehenge and Salisbury. In his biography René-Paul showed himself aware that the latter site was associated with Constable, making a rather confused allusion to ‘the Roman camp that inspired one of Constable’s paintings’, although Huet himself makes no mention of the connection in describing his visit to his wife.78 He went on to travel through the West Country as far as Cornwall and Land’s End, making sketches and watercolours along the way.

It was particularly appropriate that Huet was represented by The Flood at Saint-Cloud in London, given the English strand in its ancestry, although it is unlikely that the selection committee could have been aware of that. English commentators were just as unlikely to perceive the echo of The Hay Wain, despite the by now entrenched belief that Constable had helped to change the course of landscape painting in France. In his Handbook to the Pictures at the International Exhibition, Tom Taylor declared that ‘all modern French landscape painting’ was influenced by Constable and Bonington.79 The claim was asserted in such general and overarching terms, however, that the relationship between The Hay Wain and Huet’s painting would continue to be overlooked.