Fig.1

John Constable

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows exhibited 1831

Tate

John Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows exhibited 1831 (fig.1) constitutes one of the most extensive iconographies of the gothic cathedral that came to prominence in the Romantic era. This paper moves beyond Constable’s picture to look at the cultural and historical climate in which it appeared in 1831, and the legacy and transformation of cathedral imagery later in the century and beyond. The intention is not necessarily to posit direct influences on Constable’s cathedral, but to explore its wider contemporary contexts: ideas about the origin and development of the gothic style; the gothic affinity with nature; antiquarianism and conservation; revolutionary secularism and post-war ecclesiastical revival; patriotism and constructions of national identity; politics and society. Similarly, Constable’s picture cannot be credited with the evolution of a type of ‘universal’ cathedral – an emblem of modernist ideas, no longer rooted in a particular place or religion, made of glass rather than stone and soaring upwards to some still-undefined utopia. It can, however, be demonstrated that the cathedral as what has been called ‘a modern myth’ shared some of the same historical background.1

Trees of God

Salisbury Cathedral, Constable’s subject, is admired today as an exceptionally harmonious and coherent example of medieval gothic architecture. Mostly built in the thirteenth century, with a magnificent spire – the tallest in England – added in the fourteenth, it stands in an expansive close among meadows beside the River Avon, forming a splendid and serene ensemble. As is the case with many cathedrals, however, even the briefest historiography presents a more complicated and disputed picture than present appearances suggest. The cathedral has survived the destruction of Protestant iconoclasts after the English Reformation, later restorers and ‘improvers’, and the existential danger posed by the huge weight of its spire resting on buckling pillars and weak foundations. It was not always treated with respect or affection, even after the tide of English taste turned back towards the gothic style during the eighteenth century. While its original fabric and contents justified the author John Britton in beginning his survey of Cathedral Antiquities with a monograph on Salisbury in 1814, outrage at changes to the building made in the 1790s for Bishop Barrington – including the demolition of a bell tower and two chapels, and the mutilation of historic tombs – had ruined the reputation of the bishop’s architect, James Wyatt.2 J.M.W. Turner, depicting the cathedral in watercolours for a Wiltshire grandee, Richard Colt Hoare, established himself as its foremost iconographer before Constable, not only by his prowess in architectural topography but by negotiating a delicate balance between loyalty to Wyatt, who had employed him in his office, and the views of a patron who championed antiquarian critiques of modern alterations to historic buildings.3

Misguided alterations were not the only charges levelled against the cathedral by this time. A symbol of ecclesiastical corruption, it was in the eye of storms stirred up by the campaigns for reform of Church and State leading up to the Great Reform Act in 1832. Its tainted reputation and degraded condition helped inspire the architect A.W.N. Pugin’s zeal for a morally and socially motivated gothic revival based on ‘true Catholic principles’.4 Having moved near to Salisbury in 1835, Pugin converted to Catholicism and published his famous polemic Contrasts there in 1836.5 It sold out but made him a ‘marked man’ in the city.6 John Ruskin’s first reaction to the damp and chilly cathedral in 1848 was a bad cold. In the longer run the experience, closely followed by a tour of the cathedrals of northern France, set him on the way to his own formulation of the ‘sympathy’ between medieval gothic and nature promulgated by the earlier Romantics.7

Constable’s interest in Salisbury Cathedral arose from his friendship with John Fisher, the bishop’s nephew. Fisher’s suggestion of the ‘Church under a cloud’ for the 1831 picture has created a modern impression that its stormy atmosphere reflects their shared objections to Reform.8 Although Constable was politically conservative, his belief that, in the words of his biographer C.R. Leslie, the picture contained ‘the fullest impression of the compass of his art’ makes it scarcely credible that he confined it to this issue alone.9 Besides depicting the cathedral, it is a self-evidently a landscape and a record of changing weather. Rising like the trees around it, bridging earth and heaven, the cathedral has an organic feel and texture. The rainbow, added late to the picture, promises revival and recovery. Constable had in mind ‘rainbow landscapes’ by the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640);10 and around the time he began Salisbury Cathedral he copied out the first two lines of William Wordsworth’s poem ‘The Rainbow’: ‘My heart leaps up/When I behold a rainbow in the sky’.11

The revival of interest in gothic buildings had been under way in England for more than a century, spanning antiquarianism, historical literature and picturesque imitations called ‘gothick’.12 Medieval archaeology was a more recent development that owed much to English scholars like Thomas Rickman, who had defined the still-current phases of gothic from ‘Early English’ through ‘Decorated’ to ‘Perpendicular’ in 1817.13 Rather than such academic concerns, Constable owed more to the Romantic generation who cultivated an imaginative affinity with the Middle Ages and projected its own ideas and aspirations onto the gothic style. Freely created by people worshipping God and inspired by nature, capable of infinite permutations, to their mind gothic was the polar opposite of the rule-bound classicism of papal Italy or Napoleonic France. These notions coincided with the rise of landscape as the distinctive visual art of the Romantic age for its naturalism and ability to express what the German painter Phillip Otto Runge, promoting his art of Landschafterey, called ‘the most profound religious mysticism’.14 In Romantic ideology nature was both the product of divine will and the source of gothic form. While Constable dedicated himself to ‘natural’ painting, Germans convinced themselves they had a special understanding of nature. Their concept of landschaft – as scenic view or defined region – is as pertinent for their own national feeling as for Constable’s painterly localism.

Germans of the pre-Romantic ‘Sturm und Drang’ (storm and stress) movement, which prioritised subjectivity and extremes of emotion, came relatively late to gothic. Nevertheless, they prepared the ground for a younger generation of writers, critics, philosophers and artists who espoused it as a national art, rising from home soil and characterised by its relationship to nature.15 This chauvinist tendency emerged first as a reaction to the provincialism and inferiority complex felt across the many separate German states. It became almost a patriotic duty when Napoleon dissolved the one meaningful symbol of German nationhood, the Holy Roman Empire, in 1806 and incorporated much of its disparate territories into his own. In his 1772–3 pamphlet Von Deutscher Baukunst (On German Architecture), inspired by Strasbourg Cathedral, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had already rebranded the cathedral’s gothic architecture German and likened it to ‘a sublimely towering, wide-spreading tree of God which, with its thousand branches, millions of twigs and leaves … proclaims to the surrounding country the glory of its master, the Lord’.16 Goethe’s text (which he revisited several times) was significant in more than just its telling natural metaphors.17 Gothic buildings had long been despised by classically educated Germans, of whom Goethe was one, and the pamphlet announced a change in taste. It expressed the author’s surprise as he began to admire the cathedral against his better judgement and (as an amateur artist) to see it with a painter’s eye, observing how its densely ornamented façade (which he had expected to dislike) gradually coheres into a satisfying whole. As his perceptions change the cathedral enters a state of becoming, like religion in human consciousness, evolution in nature – or, we may guess, a nation in the making. Goethe applied the same concepts of creation and mutation in a 1790 study of the morphology of plants where they are understood as inevitable and irresistible, like the primitive will-to-form he also describes in his essay on Strasbourg.18 Goethe sourced Strasbourg’s organic gothic to individual and national genius, lauding its supposed architect, Erwin von Steinbach.19 He imagined the cathedral taking on a life of its own as the ‘strong, rugged German soul’ works on ‘the narrow, priest-ridden stage’ (that is, the unreformed Catholicism) of the Middle Ages. He described gothic is ‘our architecture’ while ‘the Italian has none to call his own, still less the Frenchman’.20

Nature and nation

Goethe later justified his ‘patriotic idea’ on the grounds that the cathedral stood in an ‘old German city’ and von Steinbach’s name sounded German too.21 Similarly circular, nationalist arguments allowed the poet and philosopher Friedrich Schlegel to declare that ‘floral and vegetable inspiration constitute the essential of [gothic] architecture, of which the true origin resides in the deep German feeling for nature’.22 For another German writer, Ludwig Tieck, the cathedral represented infinity, but a German infinity. In his novel about a young painter published in 1798, the hero and his friend, approaching Strasbourg, declare that the cathedral embodies the ‘Spirit of Man’ and ‘honours the German’.23 Revising his book in 1843, Tieck attributes it to ‘the Germans alone’, wondering if ‘we will learn one day that all the splendid buildings of this type in England, Spain and France were erected by German masters’.24 In fact, there could hardly be a less secure foundation for such wishful thinking than Strasbourg, a city in Alsace that had been part of France since 1681, is now French again after periods of German rule, and whose cathedral is recognisably French in style, having alternated between Catholic and Protestant denominations.

Who owned gothic would be fought across Europe as patriots and pundits claimed it as theirs, if not their invention then at least part of their history and identity. Almost all agreed on its organic roots while crediting their own cultures for its development and obliterating its real origins in Arab and Islamic architectural forms brought back to Europe by twelfth-century Crusaders. For the French writer François-René de Chateaubriand in Génie du Christianisme (The Genius of Christianity) (1802), the Catholic spirit of ‘l’ancienne France’ produced gothic churches with ‘carved leaves, and arboreal columns’.25 Ruskin, whose studies of the gothic focused on France and Italy, tended to think of it as Protestant and thus English by implication (only Ruskin, with his propensity for contradictory ideas, could convince himself of this when English gothic was a Catholic creation!). It was left to the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was closely attuned to European thought, to take a cosmopolitan view of organic gothic in his Philosophical Lectures (1818–19), observing that ‘a cathedral like York, Milan or Strasbourg with all its many chapels, pillared stems and leaf-work’ looked as if some ‘sacred grove of Hertha had been awed into stone at the approach of the true divinity’.26 Admirers of gothic had much in common but operated in different spheres. Enlightenment rationalism and the militant secularism unleashed by the French Revolution undermined the spiritual or feudal foundations of gothic architecture, and closed or vandalised many continental cathedrals if it did not convert them, like Strasbourg’s, to a ‘Temple of Reason’.27 This was bound to produce a reaction. But the reaction would be different for French or Germans, royalists or revolutionaries, Catholics or Protestants, let alone Britons spared the immediate consequences of such upheavals at home but afraid they might spread across the Channel. Chateaubriand’s nostalgia for the Catholic Middle Ages and fetishisation of gothic was a symptom of his legitimist conservatism, maintained during exile in England from revolutionary France, as much as his faith. In 1822, famous as the author of worldly romantic novels, he returned as the restored Bourbon monarchy’s ambassador to London. Génie du Christianisme had already rehabilitated him to the previous regime by appearing perfectly timed to coincide with Napoleon’s reconciliatory concordat with the Catholic Church – a politically pragmatic move undertaken to consolidate his power.

Fig.2

Caspar David Friedrich

Abbey in the Oakwood 1809–10

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Chateaubriand’s Catholicism was sensuous, aesthetic and ‘delicious’ to his admirers.28 He was as shocked by the desecration wrought at the German cathedral of Ulm by the home-grown Protestant Reformation as he was by the iconoclasm and anti-clericalism more recently exported from revolutionary France.29 While southern Germany had always been Catholic and there were high-profile converts – like Friedrich Schlegel in 1808 – among the Romantic generation elsewhere, German ecclesiastical nostalgia during the French occupation often originated in the Protestant, Lutheran north. It favoured the plain and natural in worship as in life and art. In paintings by Caspar David Friedrich, living trees contrast with dead Catholic monasteries or, more tellingly, are as dead as each other, as in Abbey in the Oakwood 1809–10 (fig.2). The message of these works was not just religious, however. Their bleakness evoked the despair of a subject race and called for a national revival, not a Catholic one. The gothic cathedrals Friedrich imagined borne aloft by angels or rising from rocks and trees are visions of release reaching like Tieck’s Strasbourg to infinity. For Karl Friedrich Schinkel, gothic was a ‘freely-working idea’ transcending the material.30 He admired the ‘infinitely rich and daring’ architecture of Europe’s gothic cathedrals but found them most ‘grave, dignified, and sublime’ when purged of ‘meaningless pomp’.31 Unable to build his own in French-occupied Prussia, Schinkel pictured cathedrals as backdrops for the Berlin stage, in illuminated transparencies and in a portrait of his wife. Some were multi-sensory entertainments like the diorama of a Gothic Cathedral by Water he exhibited in 1811, where soldiers crossed a bridge at sunrise while cannon fired real sparks and the organ boomed.32 In other pictures Schinkel expressed a yearning for transcendence akin to prayer.33 They were metaphorical and inspirational, just as Friedrich’s symbolic imagery was designed to bring forth multiple meanings from his inner vision and in the eye of the beholder.

Fig.3

Karl Friedrich Schinkel

Medieval City on a River 1815

Mittelalterliche Stadt an einem Fluß

Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Photo © Andres Kilger/Nationalgalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin

It would be simplistic to see the work of these artists only in nationalist or religious terms. But during the French occupation and the Wars of Liberation (1813–15) it played to German patriotic sentiment. Schinkel described the gothic as ‘putting forth shoots’, called a proposed gothic mausoleum for Queen Luise of Prussia a ‘church of nature’ and planned a vast cathedral on Berlin’s Leipziger Platz to commemorate liberation in the same style with a lofty spire like a ‘plant striving towards the sky’.34 This last idea was impossibly expensive for a post-war economy but its spire, along with English memorial crosses, found an echo in a more modest memorial to the war dead built of cast iron on the city’s Kreuzberg hill. In Schinkel’s Medieval City on a River 1815 (fig.3), celebrating King Friedrich Wilhelm III’s return from Paris the previous year, a victorious army returns to find a new cathedral rising from a grove of German oaks. Lit by a rainbow as the storm of war recedes, it flies the flag of the Holy Roman Empire perhaps soon to be reborn.

Reawakenings

Following the new emphasis on construction in Medieval City on a River, where one of the cathedral’s towers is scaffolded and not yet finished, Schinkel abandoned the gothic cathedral as a subject for painting by 1817, resuming his career as an architect – usually in the classical style. To feel the power of his painted cathedrals we need only consider the background from which they arose. Gothic ruin became a romantic motif because so many real examples existed and made such effective propaganda. Even at the height of revolutionary iconoclasm, leaving Rouen Cathedral exposed to the elements by stripping lead from its roof to supply the arms foundries of Paris caused a national scandal. After the French revolutionary Army of the Rhine overran Mainz in 1793, the publishers Artaria, who had fled to Mannheim, recorded its vandalism in prints of the ruins of the city’s cathedral and churches.35 Images like these fed the fantasies of painters like Carl Blechen whose gothic naves had gone back to nature, their decay the inevitable sequel to organic growth.36 While these had a freakish charm, real ruins cried out for repair, nowhere more than in Cologne where the huge cathedral, never finished by its medieval builders, had been laid waste by the same French army that ravaged Mainz. ‘O for the help of Angels to complete this Temple’, wrote Wordsworth after a visit in 1820.37 Requisitioned as a granary, ammunition dump, prison and quarry, and even scheduled for demolition, the remains were saved by their sheer size and the zeal of the merchant-antiquaries Sulpiz and Melchior Boisserée. Beginning in 1808 the brothers undertook an exhaustive study of the cathedral and joined Schinkel in planning its completion, publishing illustrations of what it could become.38 When their work drew Goethe to Cologne in 1815, the cathedral reminded him of ‘the inadequacy of man, the moment he undertakes something that is too big for him’.39

Recovering his early enthusiasm for Strasbourg, undermined by intervening experiences such as a visit to Milan whose cathedral had been spoilt by alterations, Goethe decided not to feel ashamed of his pamphlet of 1772: ‘For I had felt the inner proportion … recognised the development of the individual ornaments out of the whole, and discovered, after long and repeated observation, that there was something incomplete about a tower even though it was built high enough’.40 The nation-building that Goethe implies behind architectural construction was made explicit elsewhere. The Boisserées could not convince Napoleon to fund the work on Cologne to make up for previous French crimes but had more success with the Prussian Crown after it absorbed the Rhineland in 1815. This ‘national cathedral idea’ superseded the unbuilt Berlin scheme, combining a memorial to the Liberation Wars with a symbol of a future German empire. Laying the foundation stone in 1842, Friedrich Wilhelm IV declared that the ‘spirit of German unity and truth’ now finishing the cathedral was the same as had ousted the French from German soil.41

In 1823, Goethe observed that while gothic cathedrals had long been ‘a hangover from the past … how powerful has been their effect in recent times when feeling for them has been reawakened’.42 As royal and religious revivals spread across Europe after the fall of Napoleon, cathedrals were again the settings for great national occasions, such as the coronation of Charles X of France at Rheims in 1825. His predecessor Louis XVIII had brought back the full Latin mass and promoted throne and altar as twin pillars of the restored Bourbon monarchy. No such highly politicised revivalism had yet appeared in Britain, where there had been no permanent rupture since the Reformation. But the recent wars had generated interest in Anglican cathedrals by turning attention to history and heritage at home. This led to a boom in antiquarian studies, attention from artists and – less happily – from architects like Wyatt, whose alterations to Salisbury and Durham became infamous. As we have seen, Turner’s watercolours of Salisbury made in the 1790s for Colt Hoare and seen at the patron’s Wiltshire home, Stourhead, by Constable and Bishop Fisher in 1811 manage to accommodate Wyatt’s work to the original cathedral. However, at the Society of Antiquaries in 1795 and 1797, the architectural draughtsman John Carter, another of Colt Hoare’s stable of artists, attacked Wyatt for breaking ‘the long Train of historic Ideas’.43 In drawings of Durham made for the Society and salvoes against ‘Architectural Innovation’ in The Gentleman’s Magazine (1798–1817) Carter put the preservationist case.44 Colt Hoare, an Antiquary since 1793, admitted the need for repairs but argued that ‘grand Gothic structures’ must ‘bear the Character’ of their time.45 He had considered mounting Turner’s Salisbury watercolours together in a frame shaped like a gothic pointed window with, centred at the top, Turner’s view of the spire seen through a dramatically enlarged section of the cloister that arches over the cathedral like the branches of a tree.46

Fig.4

J.M.W. Turner

The Choir of Cologne Cathedral with Adjacent Houses and Townsfolk from Rhine Sketchbook 1817

Tate

Fascinated by architecture – with experience of working alongside architects including Wyatt – and echoing the will-to-form passage in Goethe’s Strasbourg essay in one of his Royal Academy Perspective Lectures, Turner extended his attention to continental cathedrals when able to travel again.47 In Cologne in 1817, he drew the cathedral alongside ‘ruined piles of old windows’, as he wrote on the drawing, and newly sawn timber (fig.4). His survey of Rhine castles and cathedrals followed one the previous year by Schinkel and the Boisserées, and like Schinkel’s additions to Berlin, including the Kreuzberg memorial which Turner drew in 1835, must have interested his architect friend John Soane whom Schinkel visited in London in 1826. No direct contact between Turner and Schinkel is known but Turner’s friend the painter A.W. Callcott knew the Boisserées, visited Cologne in 1827 and, afterwards in Munich, saw their recently published work on the cathedral. Maria Callcott thought Cologne’s ‘florid Gothic’ choir ‘magnificent’, but the rest still ‘melancholy from its wretched state – old yet not completed’.48

Constable did not travel, but acknowledged the importance of ‘primitive’ (medieval) architecture to Mrs Karl Aders, the doyenne of German culture in London.49 He also imbibed some German Romantic historicism from the younger Fisher, who wrote to him in 1828:

I met, in Schlegel, a happy criticism on what is called Gothic architecture. We do not estimate it aright unless we judge of it by the spirit of the age which produced it, and compare it with contemporary productions... we never look at the Cathedral aright unless we imagine mitred abbots and knights … I have put Schlegel into our own language, and have enlarged a little on his notion, since he only hints at the thing.50

Fig.5

John Constable

Salisbury Cathedral from The Bishop’s Ground 1823

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Via Schlegel, Fisher creates an Anglicised version of a vision of the Middle Ages that can be traced back to the art-loving friar in the German writer Wilhelm Wackenroder’s novel who is always expecting to meet a knight or a monk in medieval German towns.51 The appeal to the spirit of an earlier age as the benchmark for its architecture would echo down through Pugin to Ruskin and beyond while Constable, lecturing on ‘Gothic Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting’ in 1836, declared: ‘We contemplate them with associations, many of which, however vague and dim, have a strong hold on our imaginations’.52 Feudal society and its collective devotions were widely admired in conservative circles at this time, but Fisher and Constable had in mind the particular example of Salisbury’s historic predecessor Old Sarum, the site of the original cathedral and of England’s first parliament.53 As well as politically conservative, Constable was deeply if conventionally religious. Grounded in pietism and English Protestantism, his sense of divinity in nature could inspire him to rhapsodies worthy of his German contemporaries, both in words and paint. Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Ground 1823 (fig.5), painted for Bishop Fisher’s London house in 1823, reprises Turner’s earlier ‘general view’ made for Colt Hoare (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery) but adds an arch of trees that would not be out of place in a picture by Friedrich. Constable had ‘dreaded’ this ‘most difficult subject in landscape I ever had upon my easil (sic)’ and applied himself to ‘windows, buttresses, &c, &c’ with such exaggerated care that he was advised to show less detail for ‘breadth of effect’.54 In the 1831 view from the meadows, the cathedral is not just framed by its landscape but integrated into it, technically as well as compositionally, so that gothic as an expression of living religion is enhanced by its proximity to living things.

Fig.6

David Roberts

Rouen Cathedral 1831

Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool

Fig.7

Paul Huet

General View of Rouen from Mont-aux-Malades 1831

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Constable’s achievement in these pictures was unique in Britain. Turner never painted a cathedral in oil. If we discount the illuminated spectacles of Canterbury and Chartres Cathedrals shown by Louis Daguerre at London’s Regent’s Park Diorama in 1823–5, the only other artist depicting cathedrals on any scale or in oil was the Scot David Roberts, who painted a series of continental specimens after visiting Normandy in 1824.55 A view of Rouen exhibited by Roberts in 1826 may have encouraged Turner to revisit the city that year, and another (fig.6) was in the Society of British Artists in 1831 when Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows was in the Academy. Boldly painted, Roberts’s cathedrals are enlivened by the play of light and shade across their surfaces much as Goethe had seen at Strasbourg and Claude Monet would observe and paint in Rouen, and a later picture by Roberts of Burgos Cathedral would be criticised for lacking exactly that architectural precision Constable had been advised to avoid. Yet as urban scenes Roberts’s pictures cannot pursue the natural metaphors of gothic that Constable saw at Salisbury. Constable and Roberts, unlikely competitors who clashed over Constable’s hanging of his picture in relation to Turner in the 1831 exhibition, can nevertheless be credited with the two modes of representing cathedrals to emerge from the Romantic age – in a landscape, and in a cathedral city.56 The first was the most original and suggestive, adopted by the French painter Paul Huet for his distant General View of Rouen from Mont-aux-Malades (fig.7), shown at the Paris Salon in 1833, and later in Camille Corot’s views of Mantes or Chartres where trees and towers echo each other.57 Turner took both approaches, surveying his cathedrals from near and far.

Opinions and convictions

Later reborn in Ruskin’s writings on architecture, the Romantic notion of organic gothic gave a new legitimacy to medieval cathedrals. It rooted them in their place and made them authentic as the stylistically imitative products of the contemporary gothic revival were not. For Constable, gothic belonged to its own time, and – outside pictures – ‘modern mimicry’ was a ‘vain attempt to reanimate deceased art … to reproduce a body without a soul’.58 As Wyatt had found to his cost, many people agreed with Constable who may have remembered Colt Hoare introducing Turner’s Salisbury watercolours as well as reading Fisher on Schlegel. Across the Channel at Rouen, a cast-iron replacement for the cathedral spire destroyed by lightning in 1822 was disputed for decades, its detractors including the architect Viollet-le-Duc, the novelist Gustave Flaubert and presumably Turner who usually continued to portray the cathedral as he had first seen it in 1821. The artist John Sell Cotman’s views of the cathedral in his Architectural Antiquities of Normandy had appeared since 1819 so also showed it unchanged.59 While the style and materials used in repairs and reconstructions were often criticised on grounds of taste, motivations were also questioned. Asked why nothing like Amiens Cathedral could now be built, the German writer Heinrich Heine – a religious sceptic – replied that ‘the men of old times had convictions; we modern men have only opinions, and more than these are needed to raise cathedrals’.60 Opinions were certainly apparent in Cologne where finishing the cathedral for a new Reich became an openly political project with the intention of reconciling the Catholic, democratic Rhineland with Protestant, authoritarian Prussia. In this it signally failed, Catholicism becoming so toxic in Prussia that Catholic politicians were banned from the Catholic cathedral’s dedication service in 1880.

Heine had never put much faith in the Christian church’s ability to pacify the German character. Surveying modern Germany from his adopted France in 1834 he feared the Norse god Thor would rise again and smite gothic cathedrals.61 He was proved right when the First World War began in 1914 but had been wrong to relegate convictions to history. Far from fading, they had intensified and fragmented, gaining strength in opposition. Even staunch Lutherans or Protestants travelling in Catholic Europe might find themselves unexpectedly moved by a mass at Dresden or the piety of an Italian peasant. In Britain, where the established Anglican Church was generally acknowledged to have decayed, Catholics urged reform from without, high Anglicans, like those emerging in Oxford, from within. Meanwhile populist evangelicals and millenarians preached destruction as a prelude to the New Jerusalem foretold in the Bible’s Book of Revelation and expected to appear first in Britain. In 1829 Jonathan Martin, brother of the apocalypse painter John Martin, tried to burn down York Minster because ‘his god was not there properly worshipped’.62 This near-tragedy turned into farce later the same year, when the painter Clarkson Stanfield’s diorama of York with the Cathedral on Fire at the Royal Bazaar in London’s Oxford Street was so realistic that it set itself alight.

The ‘powerful feelings’ for cathedrals observed by Goethe and the ‘opinions’ remarked by Heine could interact in unexpected ways. The July Revolution in France in 1830 brought down the neo-feudal Bourbon Restoration and put political distance between throne and altar. It added to a febrile atmosphere in Britain where resurgent Catholicism combined with progressive politics and conservative nostalgia clashed with sometimes destructive dissent. In a highly reactionary essay England, the Fortress of Christianity (1828) the Reverend George Croly, an ultra-Tory Ulsterman, had linked Catholicism and democracy as dangers to church and state. Repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts that year and the new Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829 allowed British Catholics to worship, enter Parliament and hold public office. The 250,000 Catholics in England and Wales in 1830 would swell to 846,000 by 1850; in 1832, the Reform Bill widened the franchise and reduced corruption.63 It also reduced the historic privileges of the Anglican clergy such as the right to collect tithes, the tenth of produce paid in cash or kind by farmers to their parish. The previous year, Anglican bishops had joined the nobility in opposing the bill in the House of Lords, provoking a backlash from riotous mobs who stoned their coaches and burned their palaces. Salisbury was widely regarded as one of the most corrupt dioceses in the country while nearby Old Sarum was its most notorious rotten borough, electing two members of parliament despite having shrunk to a constituency of just seven registered voters.

Constable sided with the establishment, going so far as to describe Reform as a demonic insurgency, but at least did so privately unlike the painter Samuel Palmer who published a hysterical attack on ‘Jacobinical hyenas’ inspired by ‘atheistical France’ in a pamphlet addressed to the ‘Electors of West Kent’ in 1832.64 How far Constable advertised his political opinions in his paintings of Salisbury and the stormy 1831 picture represents ‘the Church of England in crisis’ as argued by the art historian David Bindman seems moot, given that Constable’s anger was short-lived and that he believed symbolic allegory was not readily understood in art.65 He thought his friend Fisher’s fears for his church were a ‘Phantom’ and the painted storm is passing, banished by the rainbow.66 It touches the ground near Fisher’s house in the Close, honouring the friend who had shared his vision of the medieval cathedral, consoled him as he mourned his wife and died before the picture was quite finished, taking his anti-Reform rage with him to the grave and leaving the artist’s to abate as well. The rainbow points to the afterlife, as does the cathedral’s spire; grief gives way to the hope of eternity sustained by Constable’s faith. The unity of cathedral and landscape is the natural expression of this as well as of organic gothic, just as in 1819 he had seen in ‘whatever object I turn my Eye that sublime expression of the Scripture …“I am the resurrection & the life”’.67

Sermons in stone: image and word

Fig.8

J.M.W. Turner

Distant View from Old Sarum c.1827–8

Salisbury Museum, Salisbury

While Constable was painting Salisbury during the fraught Reform years, Turner was at work on watercolours of selected English cathedrals for his definitive survey of the nation, Picturesque Views in England and Wales. Including episodes of stoning and arson as well as calmer views lit by sunshine or rainbows, they follow the emotional and narrative arc bridged in Constable’s picture. With the worst Reform battles still to come, visitors to the exhibition of England and Wales watercolours at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly in 1829 could decide for themselves if the rain-swept family in the foreground of his Distant View from Old Sarum c.1827–8 (fig.8) was a traditional Christian shepherd and his flock, as Ruskin would later argue; the rural poor made poorer by paying tithes; or even the handful of burgage voters who still returned Sarum’s two MPs. Modern scholars offer different interpretations of this work: as a favourable comparison, perhaps inspired by lines in James Thomson’s poem Spring, of ancient barbarity and modern prosperity, liberty and law under God;68 or a visualisation of the ‘native’ described by Turner in verse drafted around 1811 who no longer obeys the ‘Priests and Soldiers’ of feudal Sarum and lives by his own labour.69 Thomson’s complacency might have been all very well in earlier Georgian times. It was hardly sustainable during the rural miseries and agricultural unrest of the late 1820s, and is not supported by the evident discomfort of the shepherd’s family, huddled on their bleak knoll while the cathedral, safe under a break in the clouds, offers them no shelter.70

Fig.9

J.M.W. Turner

Rouen Cathedral c.1832

Tate

Looking at these exposed figures, rather than reading the studiedly neutral letterpress written for Picturesque Views in England and Wales, we sense that Turner was privately as in favour of Reform as Constable was opposed. His views of French cathedrals made in the early 1830s seem free of overt political or religious narratives.71 Yet it is hard not to see the sunlit crowds in Rouen Cathedral c.1832 (fig.9) – Turner’s most famous and influential cathedral image – as liberated and content, modern, yet descended from people whose faith and creative freedom had built and ornamented it. The accompanying text by Leitch Ritchie described Rouen’s ‘innumerable’ gothic details as ‘individually insignificant, yet grand and harmonious in their union’.72 This sounds a democratic note appropriate to Turner’s ‘Annual Tours’, which were directed to a mass audience, and to France, where the restored Bourbons had been replaced by the ‘Citizen King’ in the July Revolution of 1830. Turner had known the new king Louis-Philippe during his English exile, and it seems fitting that Turner’s last cathedral would be Eu, on the Channel coast, which he saw during a visit to the king’s summer residence in 1845.73

A print of Turner’s Rouen façade helped to illustrate the French writer Jules Janin’s La Normandie (1844), in which the cathedral’s past traumas – from near destruction by fire when almost new to the fall of its spire in 1822 – were recounted.74 By mid-century, and until the impressionists revived the subject for paintings, word was replacing image as the medium for describing and appreciating the gothic cathedral, with architectural surveys and treatises saturating the market. Until Ruskin turned his attention to architecture, few antiquarian or topographical publications aspired to the status of ‘literature’ except in France where Chateaubriand’s Génie du Christianisme inspired the author Charles Nodier to begin writing texts for Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France (Picturesque and Romantic Journeys in Old France) in 1820.75 In 1831, Nodier’s friend and fellow author Victor Hugo published his democratic novel Notre-Dame de Paris, in which the cathedral is presented as a book within the book – its fabric and decoration to be read by everyone as a national history.76 Hugo proclaimed architecture to be ‘the great book of mankind’.77 First translated into English by the younger William Hazlitt (son of the radical critic and essayist) in 1833, in the same decade as the architect Georg Moller’s study of German gothic appeared in Britain, Hugo’s book would later influence Ruskin’s architectural writing.78 Put off by Hugo’s anti-feudal stance and advances towards the political left, Ruskin hid the debt behind attacks on the French writer’s ‘deadly poison’, just as he covered his links to the conservative Pugin whose revivalist projects he disliked.79 He could hardly have missed these sources when gothic architecture had become a European preoccupation and ideas passed freely back and forth.

Neither an antiquarian nor an archaeologist but a polemicist, the Anglo-French Pugin drew on the romantic ideas of Schlegel and Chateaubriand, devotional critiques of architecture and art developed by the French-Scots Comte Charles de Montalambert and Alexis-François Rio, and habitual English Tory worries about national decline.80 Pugin’s Contrasts, published in Salisbury in 1836 and revised in 1841, links the ‘degraded state’ of its ecclesiastical buildings to the ‘decayed and compromising Church of England’.81 Salisbury’s Bishop Barrington and his architect Wyatt are censured yet again for ‘barbarities and alterations too numerous to recite’;82 and meanhwile the great medieval cathedrals have only survived to justify their ‘lands and oblations’, not for splendours like Salisbury’s spire.83 Advocating Catholicism and gothic as social remedies, Pugin shows himself both radical and conservative while the Ruskin scholar Robert Hewison has discerned similarly opposing traditions in Ruskin’s Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849).84 Yet in naming ‘Restorer’ and ‘Revolutionist’ as equal menaces to historic buildings that should – as many had already argued – embody the past, Ruskin is unable to acknowledge Pugin or Hugo more openly.

Witnessing the aftermath of the latest continental revolution in 1848, Ruskin looked to French cathedrals for continuity despite his evangelical objections to their Catholic ritual. He could have sympathised with Pugin’s hymn to Rouen, published ten years earlier, for surviving ‘tempests, conflagrations, heretical ravages and revolutionary violence’.85 Pugin’s Gothic revivalism, however, like his conversion, was anathema. Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice (1851–3), another study of gothic, were both written to preserve what remained untouched, while it still stood.86 Ruskin’s fullest exposition of its organic character came at the end of the second volume of Stones (1853) under the deliberately double-edged title The Nature of Gothic. Ruskin pictures gothic as a living force that rises to peaks like Rouen’s north porch, must be allowed to die but still has value for the future as a social and political, rather than aesthetic example. Musing on gothic’s inherent naturalism and eventual ‘redundance’ he rejects the convention that it derived from vegetation, preferring instead to see it growing to resemble nature as its builders discover beauty in the natural world and learn to match it in stone.87 This process is itself a natural impulse, as German Romantics had argued. Urging his readers to turn away from the modern manufactures – proof only of their servitude – in ‘this English room of yours’, he sends them ‘forth again to gaze at the old cathedral front’ and consider ‘the life and liberty of every workman who struck the stone; a freedom of thought … which it must be the first aim of all Europe at this day to regain’.88 William Morris echoed this in a preface to his 1892 edition of The Nature of Gothic – one of the first books from his Kelmscott Press – where he stated that it opened ‘a new road on which the world should travel’.89

Pugin’s ideas reached Germany partly through a pamphlet on him published in 1877 by August Reichensperger, an anglophile Catholic antiquarian closely involved in the later stages of the work at Cologne. Ruskin’s came to France through the somewhat less likely agency of the young Marcel Proust, who translated and introduced one of Ruskin’s last books, The Bible of Amiens (1885) in 1904. The outcome of a late return to France and an invitation to lecture on Amiens Cathedral to the schoolboys of Eton, the book reads the cathedral as the product of the values of its age.90 Proust was exasperated and seduced by Ruskin’s subjective mixture of morality, politics and aesthetics, and shocked by what he saw as his tendency to idolatry. But he found Ruskin’s ‘erroneous judgment often more interesting than the beauty of the work being judged’ and offered it to French readers in the same year he pronounced ‘The Death of Cathedrals’ in the newspaper Le Figaro.91 Proust’s article might seem contrarian when French cathedrals, having recovered from the Revolution and survived a century being disputed by royalists and radicals, Catholics and Republicans who viewed them very differently, were officially preserved as national treasures.92

Claude Monet’s exhibition of paintings of Rouen Cathedral in Paris in 1895 sealed their importance for the most innovative artists.93 The apotheosis of French cathedral literature, J.K. Huysmans’s novel La Cathédrale (1898) recounted a ‘mystical devotion to Our Lady of Chartres’ with so much detail on the cathedral’s structure and ornament that tourists used it as a guidebook.94 The distinctive stylistic and religious qualities of French gothic were recognised by art historians like Emile Mâle whose interest had been sparked as a boy by Hugo’s Notre-Dame but grew to repudiate its anti-feudal, democratic bias, and was called in aid by Proust in his Figaro article.95 Even Germans had come to realise that Goethe’s ‘German architecture’ was more likely to be French. Hardly had funds been allocated to complete Cologne in the early 1840s than it became apparent that Amiens had been its original, medieval model, prompting a heated ‘cathedral debate’ that even reached the German parliament. The nationalist strand in Goethe’s reappraisal of gothic, once so influential, was superseded by a narrative of Germanisation through assimilation and synthesis into such art-historical sleights of hand as ‘German special gothic’ (Sondergotik).96 France’s cultural gain was offset by the strategic loss of Strasbourg and its splendid cathedral to Germany in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871. A militant Germany was not Proust’s concern in 1904, however. Instead he saw danger within, from a new wave of anti-clericalism threatening to sweep away the old concordat of church and state that was as much part of France’s identity as her cathedrals. Rouen had seen anti-clerical riots, with demonstrations outside the cathedral and firecrackers let off in the nave, as recently as 1888.97

Impressions and symbols

Fig.10

Claude Monet

Rouen Cathedral: Setting Sun 1892–4

National Museum Wales, Cardiff

Fig.11

Camille Pissarro

The Roofs of Old Rouen, Grey Weather (Cathedral) 1896

Les toits du vieux Rouen, temps gris (la cathédrale)

Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio

While impressionist painters had revived cathedrals as pictorial subjects in recent decades, how far if at all did these motifs reflect external circumstances? Were they self-sufficient, or screens for transient effects? Monet was not religious, nor was his interest in architecture antiquarian or historical. The rough texture of his Rouen series, resulting from frequent studio revisions, evokes carved stone without any of the details that could now be documented in photographs. Rather, they show the cathedral in varied lights and shades such as dawn and sunset (fig.10) and affected by his own changing moods. Camille Pissarro’s title for his profile of the cathedral riding above Rouen like a great ship on a stormy sea (fig.11) cites the rooftops and the damp and gloomy weather (‘temps gris’), only mentioning the cathedral in parenthesis. Neither painter, however, can have been immune to its significance as a national monument, its contested history or its place in art. The art historian Paul Hayes Tucker has argued for a patriotic role for Monet’s most characteristic French subjects.98 Pissarro acknowledged earlier ideas when, in Rouen in 1896, he remarked ‘how close to nature’ were the ‘true French Gothics’.99 Both artists reclaimed for France motifs and viewpoints previously made familiar by Turner, and the serial approach adopted by both Turner and Constable. In London in 1887 and 1889 respectively, Monet and Pissarro missed the exhibition of Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1888. But Monet may have seen Turner’s study of Rouen’s west front in the National Gallery as well as in reproduction; Pissarro, finding himself in Turner’s footsteps in Rouen, asked his son Lucien who was in London to copy Turner’s view of the city and cathedral, a subject he was thinking of painting himself.100 Pissarro, with his Jewish heritage, rejection of organised religion and radical, even anarchist politics would have recoiled from medieval Catholicism. But he was competing with Monet’s Rouen series, visited the exhibition at Durand-Ruel and discussed Monet’s ‘extraordinary mastery’ of ‘fugitive effects’ with his fellow artists.101 Some critics of Monet’s pictures (like those of Constable’s in 1831) did not address the cathedral at all, let alone gothic. Raymond Bouyer, who did, was shocked to find the ‘pious cathedral crumbling under an atheist sun’.102 Camille Mauclair thought Monet’s ‘pagan art’ unfit for Christian architecture.103 Others thought Monet had revived the age of faith or achieved an ‘assumption of the cathedral’, and the painter Henri-Edmond Cross even heard an exhibition visitor exclaim ‘one can hear the organ’.104

Pissarro told his son that Monet’s cathedral series was controversial (‘très combattu’).105 Partisan or conflicted reactions were to be expected in the contentious climate of the French Republic.106 Painting the cathedral as repeatedly as he did altered Monet’s own perceptions. He had nightmares of it looming over him, crushing him not like a tree but a cliff, a geological variation of the biological metaphor repeated by Emile Gallé when, echoing Goethe, he compared gothic architecture to the morphology of plants.107 For his library at Giverny Monet acquired a copy of Huysmans’s La Cathédrale, as might more readily be expected of symbolist contemporaries who made cathedrals some of their most suggestive images. Transcendence, mystery, yearning for the spirituality and collective will of a vanished age when anonymous builders, the people, could raise the greatest works of art, were powerful attractions even if separated from religion. Explaining the symbolist aesthetic in 1895, the artist Maurice Denis cited gothic cathedrals, Gregorian chanting and ‘primitive’ art to show how human feelings and emotions inevitably find their plastic equivalent and corresponding beauty. If this sounds like an echo of Goethe’s will-to-form, it departs from his romanticised view of individual national genius epitomised by Erwin von Steinbach. Similarly, when symbolists followed romantics in comparing gothic cathedrals to forests, they sometimes inverted the simile, to more disturbing effect. Their poet-apostle Charles Baudelaire had begun his poem ‘Obsession’ in Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) with the sinister injunction ‘Great woods, you frighten me like cathedrals’.108

In 1907, the sculptor Auguste Rodin discussed writing a book on gothic cathedrals with the Francophile German Count Harry Kessler. Rodin’s Les Cathédrales de France appeared in the spring of 1914, with an introduction by Charles Morice proclaiming their rediscovery and resurrection – just months before the destruction foreseen by Heine began.109 Rodin’s famous statement that ‘all our France’ is in her cathedrals spoke to their cultural history as much as to the buildings themselves. Like others before him, he asserted the cathedrals’ national character as expressions of the French soul, soil and landscape. He preferred them ruined than restored. Rheims Cathedral, his ‘wonder of wonders’, inspired a passage more exalted even than Goethe’s on Strasbourg’s, foretelling ‘Sublime apotheosis! Holy terror!’.110 By mid-September Rheims was a burnt-out shell, the first great cathedral to fall to German guns; Soissons, Arras, Verdun, Louvain and others followed. Heine’s vision of the destroying Thor was invoked in German and French propaganda and the martyr-cathedral became a symbol of threatened nationhood and enemy barbarity. It signified more, to a far greater number of people, than the romantic forest-cathedral or the more elusive and ethereal structures envisioned by the symbolists. Reversing Goethe’s questionable insight and following the later ‘cathedral debate’, patriots urged replacing the use of ‘gothic’ to describe medieval architecture with ‘French’.111 Mâle’s scholarship was co-opted in the campaign, losing credibility it has yet to recover in Germany; while to regain ground lost in the propaganda war German experts were enlisted to show the world that measures were in place to protect and conserve monuments in occupied territory or on the Western Front. This was more about image than reality, but not entirely cynical. With modern French culture pervasive across Europe and Paris a longstanding retreat for German intellectual dissidents from Heine to Karl Marx many Germans were privately Francophile. Otto Grautoff, the art critic who led German cultural propaganda from late 1914, had written on Rodin (1908) and Monet (1912).112 The painter Franz Marc, passionately anti-war by the time he was killed at Verdun in 1916, had first welcomed it as a necessary purge, making way for a new Europe based on French ideals. In fact, German perceptions of unjust defeat in 1918 revived the old quest for Germanness, not least as manifested in gothic, but tempered it with the fear that it was a lost cause. Having to return Strasbourg, the archetype of Goethe’s ‘German architecture’, to France was a symbolic blow and the art historian Wilhelm Pinder, writing in 1920, claimed France was outlawing admiration for anything German.

Crystal and glass: cathedrals of utopia

As historic cathedrals were destroyed new ones arose in the mind. These were not Christian but utopian, heirs to the secularised ‘new churches’ and temples of reason of the French Revolution. Made of new materials, they remained essentially gothic in form, imagined from the natural materials that had fascinated the Romantics. Describing how Cologne Cathedral might look when finished, Friedrich Schlegel had supposed it would appear from afar like a forest but turn as he approached into a vast formation of crystals.113 For A.W. Schelling, the crystalline revealed the ‘spiritual within the material’.114 Crystallography, a branch of mineralogy introduced to Germany at the turn of the nineteenth century, offered new images for the process of construction more purely cerebral than the vegetable forest. In 1914 the expressionist architect Bruno Taut contributed a transparent crystalline structure to an exhibition held by the Werkbund in Cologne.115 It was dismantled when war broke out but meanwhile he had planned a vast building of glass, steel and other modern materials that would recruit all the arts as cathedrals had in the Middle Ages. It was, he wrote, ‘a Necessity’ but for no purpose other than to surpass itself.116 A modernist successor to Schinkel’s unrealised Liberation cathedral, potentially the apotheosis of the Romantic dream of a total work of art, it looked to an unspecified future rather than the past.

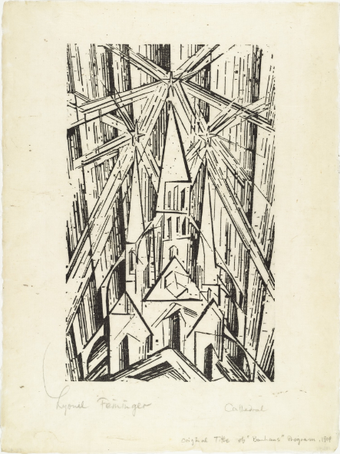

Fig.12

Lyonel Feininger

Cathedral 1919

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

After the German defeat and the November Revolution that overturned Imperial Germany in 1918, the collective will that had raised medieval cathedrals was invoked again in what the philosopher Ernst Bloch called a ‘mixture of Marx and prayer’.117 Writing of Rheims the same year, Adolf Behne paraphrased Rodin by stating ‘the cathedral is itself a people’.118 The Bauhaus, founded in 1919, dreamed of its own ‘building of the future, rising into the sky from the hands of a million workers, a crystal symbol of a new faith to come’.119 The American-born painter Lyonel Feininger, who had emigrated to Germany in search of his roots, pictured this aspirational vision in the Bauhaus manifesto (fig.12). His is a crystal cathedral, towers and spire rising into the cosmos through shafts of light like searchlights and stars like bursting shells, leaving behind the horrors of war and its gothic predecessors which, as the poet Alfred Knoblauch had told Feininger in 1917, were now ‘lonely watchers over sunken cities’.120

These crystalline fantasies had no basis in religion; they were cathedrals without God. The greatest of all glass buildings, London’s Crystal Palace, had been devoted to manufactures, commerce and Empire; Victorian railway stations, with their glazed vaults and forests of cast-iron columns, serviced mass transport. As the Bauhaus embraced functionality, the modern cathedral was as likely to be a sports hall or factory, a skyscraping office tower or a department store such as the one Hans Scharoun, a member of the ‘Glass Chain’ group of architects and designers, imagined rising over Berlin’s Friedrichstrasse in the early 1920s.121 Today’s secular cathedral is an art gallery or a shopping mall. For much of the twentieth century, it seemed as if the medieval gothic cathedral was lost to art, and in 1968 the art historian Ludwig Grote, who had been closely associated with the Bauhaus, observed that ‘pursuing the cathedral idea’ remained a task for the future.122 The decline of religion, at least in the West, would be a factor in erasing this once compelling preoccupation only in so far as religion had determined its reappearance in the Romantic period. The dwindling of antiquarianism, rejection of competing nationalisms and reaction against the adoption of Romantic ideas by Nazi ideologues contributed as well.

Fig.13

Dennis Creffield

Peterborough: Approaching the West Front 1987

Tate

© Dennis Creffield

Nevertheless, the destruction wrought by yet another war brought a revival of interest. John Piper, a devout Anglican and lover of Romantic art and medieval churches, painted the ruins of Coventry Cathedral shortly after it was bombed in 1940. He depicted York Minster from Clifford’s Tower for Hans Hess, director of the city’s art gallery and a refugee from Nazi Germany whose father had been a founding sponsor of the Bauhaus and a friend of Feininger. As a ‘Homage’ to Constable, he made a watercolour of Salisbury Cathedral overhung by trees.123 The ‘cathedral idea’ in modern art was taken up by the art historian Donat de Chapeaurouge in an article on Corot published in 1973, and later pursued more broadly in exhibitions in London, Rouen and Cologne.124 In 1987 the Arts Council of England commissioned Dennis Creffield to do what even Turner had never managed and draw all of England’s medieval cathedrals. Exemplified by his Peterborough: Approaching the West Front 1987 (fig.13), these were energetically rendered in charcoal, often filling entire large sheets of paper. They recall Monet’s Rouen but with the religion restored – adding, as Creffield explained, ‘my glory to their glory which came from the glory of God’.125 Describing his project for an exhibition of the drawings in 1987, Creffield ranged over the cultural history of gothic. He described Rodin’s Cathédrales as ‘not an architectural treatise – but a loving and passionate advocacy’;126 Ruskin’s ‘broader polemic’ in Seven Lamps and Stones;127 and the Romantic conception of organic gothic that Constable adopted and Ruskin adapted.128 He pictured Salisbury’s north side ‘as green as the river from which it springs’;129 and related how at Southwell ‘stone is transformed into plants’.130 This, Creffield related, occurred ‘not by superficial imitation of their appearance but by becoming the growing thing – entering the spirit of the growing thing – yet remaining itself’ just as Constable’s cathedral does as it rises from the meadows.