Fig.1

François Kollar

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica 1937 displayed in the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World Fair, 1937

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais and François Kollar

In 1940, the year he joined the underground Communist Party, the Sicilian artist Renato Guttuso received a postcard of Pablo Picasso’s 1937 painting Guernica (Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid). It was sent to him in Rome from New York by the art historian and critic Cesare Brandi, and Guttuso carried it in his wallet until 1943, the year of Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini’s fall, describing it as ‘an ideal membership card of an ideal party’.1 It was a view shared by one of Guttuso’s contemporaries, the critic Mario de Micheli, who would later recall making reproductions of Guernica at Milan’s Castello Sforzesco art library for distribution among his friends as badges of allegiance.2 Commissioned for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World Fair in Paris, Picasso’s mural-sized painting was designed to raise awareness of the plight of the Republican government in Spain’s ongoing civil war, in which the Nationalist rebels, aided by fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, were gaining ground (fig.1). In this most public of settings, Picasso applied the pictorial language he had developed through cubism and surrealism to an urgent political and humanitarian crisis. Guernica was thus revered by Guttuso and his colleagues as a model of political engagement without stylistic compromise.3 As art historian Christopher Green has argued: ‘Guernica was the most ambitious modernist painting of the 1930s to marshal the weapons of attack honed in the interwar avant-gardes for an explicit political purpose, aimed against a specific target, the fascist Right.’4 For this reason, Picasso’s mural was seen as the archetypal resistance artwork by Guttuso and other members of Italy’s left-wing avant-garde seeking to oppose fascist oppression during the latter stages of the regime.

From the late 1930s onwards, Guttuso made repeated reference to Guernica in his art and writing. Picasso’s rejection of partisan motifs in favour of a more universal iconography of suffering made Guernica readily applicable to contexts other than the one for which it was made. Guttuso, accordingly, found in Guernica the language with which to confront the violence of the Italian mid-century, from fascism and the Nazi occupation to the era of Christian Democracy and the Cold War. This article will examine Guttuso’s sustained dialogue with Guernica, focusing on the period between its initial exhibition at the Paris World Fair in 1937, when he encountered it vicariously, and its display as part of a major retrospective of Picasso’s work in Milan in 1953, when Guttuso would at last see it in the flesh. The Paris and Milan exhibitions bookend the period of Guttuso’s most urgent political engagement with Guernica, when he most consistently cited Picasso in order to intervene in the circumstances of his time.5

I shall argue that Guttuso’s incorporation of Guernica into an Italian language of resistance was consistent with the symbolic strategy of the Communist Party in post-war Italy, which drew inspiration from the political theories of Antonio Gramsci, Italian communism’s most original thinker. As the artist chosen to represent the Italian Communist Party (PCI) on its first post-war membership card, Guttuso and his work can be seen to occupy a place of particular importance within the symbolic universe of the PCI as it became a party of mass membership in the wake of the resistance. He would, after the war, become the most prominent Italian communist artist of his generation. By investigating Guttuso’s repeated citation of Guernica, this article seeks to shed light on the place of visual art in communist constructions of history. More broadly, it explores appropriation as an instrument of protest art, adding to the growing body of literature on Guernica’s ongoing afterlife, or what art historian Jonathan Harris has described as ‘its life as icon-symbol’.6

Guernica as talisman

By the time Guttuso received Brandi’s postcard in 1940, Guernica’s status as avant-garde agitprop was firmly established.7 Picasso’s canvas was an outraged response to the suffering inflicted on the Basque town of Guernica by German and Italian warplanes acting on behalf of the Spanish Nationalists, led by General Francisco Franco. The attack, which took place on 26 April 1937, shocked the international community for the unprecedented way in which it targeted civilians with saturation bombing. Following its exhibition at the Paris World Fair, Guernica embarked on a tour of Scandinavia (1938) and England (1938–9) to raise funds and awareness for the Republican campaign, capitalising on the high-profile status of both the subject matter of the mural and its artist. Arriving in New York on 1 May 1939, after the defeat of the Spanish Republic that would see General Franco rule over Spain as dictator until his death in 1975, Guernica was exhibited around the United States to raise money for the Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign. The painting was returned to New York for a Picasso retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) from November 1939 to January 1940. It toured the US again, as part of that exhibition, until the summer of 1943, when it was installed at MoMA for safekeeping under Picasso’s instructions that it should be returned to Spain only when the Republic had been restored.8

The perception of Guernica as a watershed in anti-fascist art making was widely shared within Guttuso’s circle at this time. In a letter to the critic Giuseppe Marchiori, dated 2 June 1944, the Milanese painter Renato Birolli described it as ‘a historical turning point’ that heralded a new era: ‘If Guernica is an indication, we are saved’, he wrote.9 Birolli and Marchiori, like Guttuso, had been part of the group of artists and intellectuals that gathered around the Milanese journal Corrente in the late 1930s. The group harboured a cultural resistance to the fascist regime that prefigured the armed resistance in which a number of its members would later participate.10 Their primary model for that cultural resistance was Guernica. The Corrente painter Ennio Morlotti, who raised awareness of Guernica in Italy as one of the few Italian artists to have visited Paris during the World Fair of 1937,11 summarised the position of the group in his ‘Letter to Picasso’, published in the first issue of the militant cultural review Il ’45 in February 1946: ‘With Guernica we began to want to live, to leave prison, to believe in painting and in ourselves’.12 Mussolini’s contribution to the Spanish Civil War – which saw him supply troops and material aid to support the Nationalist campaign – and the involvement of Italian planes in the bombing of Guernica made Picasso’s mural a particularly compelling prototype for these young artists: in Guernica they found both a model of artistic engagement and a direct protest against the actions of the regime that they, too, opposed.13

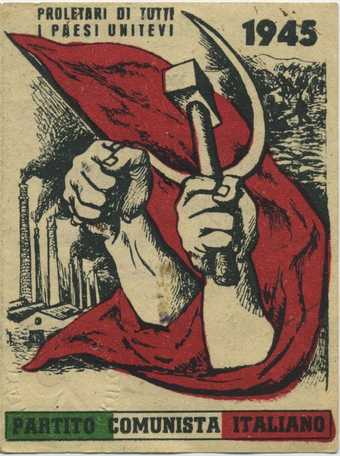

Fig.2

Renato Guttuso

Membership card of the Italian Communist Party, 1945

© Fototeca Gilardi

For all its unifying idealism during the fascist years, Guernica would become a rather vexed model for this group of left-wing artists in the years that followed Italy’s liberation in April 1945. Early signs of these difficulties can be found in Guttuso’s design for the first post-liberation membership card of the PCI, in which the imagined ideal of Guernica was rejected in favour of didactic socialist statement (fig.2). Beneath a header bearing the rallying cry of the Communist Manifesto – ‘Proletari di tutti i paesi, unitevi!’ (‘Workers of the world, unite!’) – Guttuso paired scenes of industrial and agricultural labour, linked by a draped red flag from which two disembodied arms emerge, fists raised, one clutching a hammer, the other a sickle. The shift from Guttuso’s wartime imagining of Guernica as an ‘ideal membership card’ to the didactic realism of his actualised version eloquently demonstrates the communist dilemma with regard to Picasso, whose stylistic divergence from the Party’s preferred realist mode would complicate the kudos brought by his allegiance. It was a problem that first surfaced at the time of Guernica’s making – as Green puts it, ‘how effectively could modernist art be an art of opposition in the political arena?’ – and would resurface when Picasso joined the French Communist Party in 1944.14

By taking a membership card of his own, Picasso vindicated the conviction these young Italian artists had shown in adopting his work as their unofficial badge of allegiance. His adherence to the French Party was commemorated in late 1944 by the Italian communist press, which had resumed full publication following the liberation of Rome in June that year.15 The newly founded magazine La Rinascita (‘the rebirth’), named for the cultural and political renewal it sought to inaugurate, published a modified translation of Picasso’s own account of his new allegiance, first printed in the American Marxist magazine New Masses in October 1944.16 Tellingly, the Italian version enhanced the militancy of Picasso’s description of his artistic practice, and emphasised the inevitability of his communism. Translated into English, it reads:

My adherence to the Communist Party is the logical consequence of my entire life, of my entire career. As, I am proud to say, I have never considered painting an art of mere pleasure, as a distraction; I wanted, with design and with colour, as these were my weapons, to penetrate deeper into a knowledge of the world and of men, so that this knowledge might free us all.17

Published as Italy’s war of liberation continued in the north of the country, Picasso’s statement of allegiance must have raised the spirits of those artists on the left who had contributed their work, cultural and otherwise, to the resistance movement. Yet they too acknowledged that Picasso’s presence among their ranks could not be greeted without qualification.18 Writing in the PCI organ L’Unità on 24 December 1944, Guttuso offered ‘comrade Picasso’ a welcome that anticipated these concerns:

We mean to say that Guernica is, yes, a typical product of the civilisation from which it is born, and yes, it is stylistically tied to the intellectualistic schemes of Cubist painting and of Picasso himself, and yes, it is tied, in its form and in its language, to all of the artistic baggage of capitalist bourgeois society, but in its essence, it is a new work, it is a cry of revolt and of vendetta.19

Both articles sought to repackage Picasso for communist consumption. They attest to the emergence of a preferred reading of Picasso, focused on Guernica, which sought to diminish those aspects of his practice that conflicted with the nascent cultural politics of the PCI, and to highlight those that evidenced political activism.20 As we shall see, the attempt to navigate these tensions would shape Guttuso’s engagement with Guernica – in his art as well as his writing – in the years that followed.

Gramsci and communist (art) history

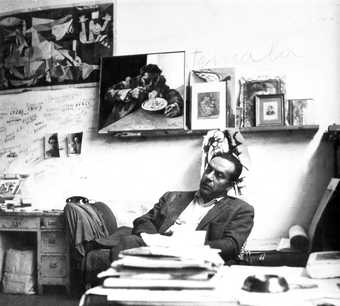

Fig.3

Renato Guttuso in his studio at Villa Massimo, Rome, 1956

That Guernica remained a touchstone for Guttuso well beyond the war years is evident in a photograph of his studio at Villa Massimo in Rome, taken in 1956 at the height of the Cold War (fig.3). It shows a poster of Picasso’s mural tacked to the wall above a photograph of Marxist philosopher and communist politician Antonio Gramsci, who had died in the year Guernica was painted, on the day after the bombing of the Basque town. Gramsci had been one of the founding members of the Communist Party of Italy in 1921, later becoming its leader. Following his arrest by the fascist authorities in 1926, he endured more than a decade of imprisonment, during which time his health deteriorated and his theoretical writing flourished. His major contribution to twentieth-century political thought, the so-called Quaderni del carcere (Prison Notebooks), were produced during his prolonged confinement. Already regarded by his allies as a heroic victim of the fascist regime at the time of his imprisonment, his death from a brain haemorrhage shortly after his release assured his martyrdom, and with it his place in the pantheon of Italian communism.

One of the most influential cultural ideas to emerge from Gramsci’s prison writings was the concept of the national-popular. As cultural historian David Forgacs puts it, the national-popular was a ‘form of culture in which there was an organic relationship between Italian intellectuals and the broad national masses’.21 This, Gramsci argued, had been missing from Italian culture, which had been characterised historically by a detachment of the intellectuals from the people. As a result, Forgacs and film historian Geoffrey Nowell-Smith argue, ‘the Italian nation had … been more a rhetorical or a “legal” entity than a felt cultural reality’.22 Developed in response to fascism, Gramsci’s concept of national-popular culture was intended as a means of bringing about “revolutionary change” by transforming ‘popular mentalities and behaviour’, as Forgacs puts it.23 This was central to Gramsci’s strategy for bringing socialism to power in Italy, which, he argued, required a different approach to the Russian revolutionary model of a direct attack upon the state. The strength of civil society in the West, Gramsci argued, demanded a more gradual approach.24 Working class hegemony would have to be established with ‘exceptional qualities of patience and inventiveness’ in order to prepare the ground for power.25 In this, the alliance between the working class and other social forces opposed to the capitalist ruling class would be essential, and the role of intellectuals in ‘coordinating and leading’ those forces would be crucial.26 According to this model, a national-popular culture that brought intellectuals into dialogue with the people would play a critical role in the struggle towards working class hegemony.

These ideas informed Palmiro Togliatti’s leadership of the PCI from March 1944, when he returned to Italy from exile in Russia.27 Having become leader in November 1926 following Gramsci’s arrest – a fate he himself had escaped on account of being in Moscow on Party business – Togliatti had, until this point, led an outlawed party from a position of exile. His return to Italy marked a major turning point in PCI strategy, which was to prioritise Italy’s liberation from fascism over socialist revolution. In adopting a position of national unity in response to the particular circumstances of Italy, Togliatti was influenced by Gramsci’s thinking on socialist strategy.28 Though the first volume of the Prison Notebooks would not be published in Italy until 1948, Togliatti had had access to Gramsci’s unpublished writings in Moscow, and incorporated them into his own ‘Italian road to socialism’, as Togliatti’s Gramscian strategy was known.29 The concept of the national-popular would gain currency in the late 1940s and 1950s when the Prison Notebooks were published and began to inform the official cultural policies of the PCI, notably in its promotion of socialist realism and the so-called andata al popolo, the practice of artists and intellectuals going to work among the people.30 The party’s first cultural resolution, issued on 1 March 1948, adopted a Gramscian stance in calling for ‘the unity of Italian culture, which can only overcome its fragmentary nature through participation in the life and struggles of all the people’.31

While this resolution would crystallise the political engagement of Guttuso and other communist artists at the end of the 1940s, the roots of his national-popular turn can be traced to the late fascist period a decade earlier, when, as we have seen, Guernica was held up as a beacon of artistic engagement for revolutionary change. In pairing Gramsci’s portrait with Picasso’s mural, Guttuso made a shrine of his studio wall (see fig.3), paying homage to the anti-fascist icons of the interwar years, which continued to motivate him twenty years later. As Forgacs has shown, this particular photograph of Gramsci was iconic both in terms of its fame and the reverence it inspired.32 It was, invariably, this portrait that was hung on the walls of Communist Party branches across Italy from the late 1940s. Its display both commemorated Gramsci’s martyrdom and celebrated the survival of his legacy. It thus became emblematic of the narrative of continuity constructed by the party under Togliatti’s leadership. Acting under Gramsci’s watchful eye, the PCI drew a direct line between its post-war programme and the actions and ideas of its most venerated anti-fascist martyr. By hanging the party-approved portrait on his studio wall, Guttuso situated his own practice beneath this same Gramscian gaze, reaffirming the narrative of continuity from anti-fascism to post-war socialism, which found its artistic equivalent in the displaying of Guernica. The arrangement of his studio wall suggests an equivalence between Guernica and Gramsci’s portrait, whose fame and inspiration of devotion it shared. In the manner of the postcard he envisaged as an ideal membership card, the poster of Guernica, displayed alongside Gramsci’s portrait, staged Guttuso’s studio as an ideal party branch, where the compatibility of Gramsci and Guernica could be maintained, and the lesson of Picasso could be understood as national-popular.

By the time Guttuso posed for the photograph in his Villa Massimo studio in 1956, the Party’s reservations about the accessibility of a pictorial language informed by Picasso were well established. The so-called picassismo of Guttuso and other artists of the left, such as Giulio Turcato and Emilio Vedova, had been robustly condemned by Togliatti in the autumn of 1948. The fragmented forms that characterised the neo-cubist style practiced by Guttuso and others in the late 1940s were the target of a vitriolic attack by the PCI leader in the pages of Rinascita.33 Responding to an exhibition of such works in the Prima mostra nazionale d’arte contemporanea at Bologna’s Palazzo Re Enzo, Togliatti condemned their ‘geometric and anatomical eccentricities’, arguing that ‘they speak of nothing to us and to ordinary men’.34 This outburst, which amounted to the prescription of a realist idiom and divided communist artists, was itself a response to pressures from the international communist community, and from within the PCI, to impose cultural orthodoxy.35 This cultural calling to order should also be understood in the context of the political failure of the left in the general election of April 1948, and the widespread social unrest that followed an attempt on Togliatti’s life that July.36 It marked a radical shift from the apparent openness to cultural pluralism that had seen artists and intellectuals flock to the Party in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War.37 Although Guttuso would remain loyal to the Party, developing a more accessible realist language in the wake of the Rinascita debate, it is clear that he would continue to see Guernica as the archetype of politically engaged art.

It was, after all, in Gramscian terms that Guttuso had defended the revolutionary character of Picasso’s work. Writing in L’Unità in November 1947, he intervened in the fallout that followed the criticism of Picasso and Henri Matisse in the Soviet newspaper Pravda that summer. The socialist realist painter Alexander Gerasimov had condemned the ‘formalism’ of the two artists’ work as bourgeois and decadent, prompting suggestions that Picasso had been ‘excommunicated’ by the Party.38 Guttuso’s response, which allowed space for Pravda as well as for Picasso, echoed the logic of Gramsci’s national-popular strategy:

Picasso is and remains a great painter, probably the greatest painter of bourgeois capitalist society … in the objective, historical sense of time and place. He is that which we all are, an actor in a society; a society we do not like, that we find unjust and monstrous, and against which we rebel, but within which we are … He is not a Soviet artist born in a socialist society, but a Spanish painter who, in the culture of his and our time, and with the means that this culture allows him, has made revolutionary work.39

While the means allowed to artists working within the culture of the PCI would soon become significantly more restricted, Guttuso’s esteem for Picasso as the leading (communist) artist of the West would survive the watershed of 1948. As the display at his Villa Massimo studio suggests, for Guttuso the Picasso of Guernica remained compatible with an idea of popular realism. Prominently placed on the shelf before which Guttuso sits is a painting he made the year the photograph was taken: Uomo che mangia gli spaghetti (The Spaghetti Eater) 1956 (private collection). A modernist reworking of Annibale Carracci’s Bean Eater c.1583–5 (Galleria Colonna, Rome), Guttuso’s painting describes an everyday scene in realist mode. Like Carracci before him, Guttuso presents an unflinching portrait of a working man in the act of eating. The closely framed figure in a hunched pose – mouth open, fork full – describes the urgency of eating after the fatigue of labour. Taking Carracci’s painting as its source, Guttuso’s canvas typical of his work in a decade that saw communist artists turn to Italian artistic heritage in pursuit of a national-popular tradition.

These efforts were centred on Realismo, a monthly journal for the figurative arts launched in Milan in June 1952 to provide a forum for the contemporary realist movement.40 It advocated for an Italian form of socialist realism, which paralleled the Italian road to socialism pursued by the post-war PCI, under the influence of Gramsci’s thought. The journal sought to situate the work of contemporary artists within a national tradition, constructing a genealogy of Italian realism from the Renaissance to the present.41 In doing so, it created a distinctly Gramscian framework for contemporary realism, arguing in its first editorial that the movement sought ‘to repair that separation between art and the public, between culture and life’.42 It traced the origins of this pursuit to ‘the culture of anti-fascism and the Liberation’, for which, as we have seen, Guernica was a major point of reference.43 The arrangement of objects on Guttuso’s studio wall – the overlapping of Guernica with a work of historically inspired popular realism in the presence of Gramsci – displays Realismo’s arguments in pictorial form. If Uomo che mangia gli spaghetti reveals the more accessible pictorial language Guttuso would pursue in the 1950s, the way in which it is positioned and photographed in his studio acknowledges the avant-garde as well as the anti-fascist origins of that realist mode, and in doing so proposes a Gramscian reading of Guernica.

Art against Barbarism

Guttuso’s repeated recourse to Picasso, like his tribute to Carracci, can be understood as part of a broader tendency towards art historical citation in communist protest art, dating to the years of resistance and liberation. In August 1944, two months after Rome’s liberation from Nazi occupation, the exhibition L’arte contro la barbarie (Art against Barbarism) opened at the Galleria di Roma. Organised by L’Unità, with the PCI leader Togliatti presiding over its Honorary Committee, the exhibition presented work made in opposition to Nazi fascism by Rome-based artists. As the struggle for Italy’s liberation continued north of the capital, the exhibition showcased Rome’s cultural resistance through contemporary interpretations of iconic revolutionary artworks: Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat 1793 (Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels) was reworked by Ugo Rambaldi; François Rude’s The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792, better known as La Marseillaise 1833–6 (Arc de Triomphe de l’Etoile, Paris), by Mirko Basaldella; Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808 1814 (Museo del Prado, Madrid) by Guttuso; Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People 1830 (Musée du Louvre, Paris) by Mario Mafai; and Aleksandr Deineka’s The Defence of Petrograd 1928 (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) by Giulio Turcato.44 As art historian Adrian Duran has observed, the subject matter of these works – martyrdom, popular insurrection, resistance to foreign occupation, the defence of capital cities – resonated with the contemporary experiences of the Italian people.45 In adopting the language of their revolutionary precedents, these paintings and their collective exhibition situated the Italian resistance movement within a historic lineage of revolution. By claiming this revolutionary tradition as its own, the Italian Communist Party – the leading force within Italy’s resistance movement – sought to position itself as the guardian of the political and cultural rebirth of the post-fascist nation.46

As art historian Nicoletta Misler has argued, Art against Barbarism’s homage to the politically engaged art of other nations can be seen as a template for the national-popular tradition that Gramsci had found lacking in Italian culture.47 As well as allowing the exhibition to sidestep the politically compromised history of Italian modernism,48 the recourse to international models of revolutionary art highlighted the absence of a national-popular culture in Italy, which Gramsci had associated with the nation’s non-history of popular revolution. If the development of a national-popular tradition was, for Gramsci, to be a prelude to revolutionary change, then the ambitions of this exhibition seem clear. Writing in the pages of Rinacista, one of the exhibition’s organisers, the communist critic Antonello Trombadori, described it as a new beginning, in Gramscian terms. It was, he wrote, ‘an important event in the cultural and artistic life of our country’ on account of the artists’ recognition that ‘art can no longer be something detached, separate, intangible and exclusively bound to its peculiar and autonomous rules’.49 The position adopted by the artists, he argued, ‘cannot but serve and arise from the working-class movement on the path to progress’.50

The historical approach evident in the Art against Barbarism show – the construction of a narrative of Italian anti-fascism in the language of earlier revolutionary history – was consistent with the Italian Communist Party’s symbolic strategy, as defined by historian David Kertzer, of framing the present through the past.51 Examining the history of the PCI in the wake of its dissolution in 1991, Kertzer adopts an anthropological perspective in order to highlight the importance of symbolism in motivating political allegiance. As Italy’s second largest political party, and the largest and most successful Communist Party in Western Europe, the PCI enjoyed considerable support in the post-war years. Kertzer maintains that the Party’s ‘successful construction of history’ was central to its appeal, and that: ‘This history was both outward looking – casting an eye on the rest of the world, producing a PCI view of world history – and inward looking, holding itself up for inspection, producing a self-history.’52 Both aspects of this history-making were in evidence in Art against Barbarism, in which artworks relating to key revolutionary episodes in world history were reinterpreted to produce the Party’s self-history in the form of the myth of the resistance, which was to be, as anthropologist Jaro Stacul has argued, the major ‘source of legitimation of the PCI’s past and present’.53 As Kertzer puts it, ‘“making history”’ means ‘“making a future” as well as “making a past”’.54 I want to argue that the tactics of appropriation adopted by Guttuso represent a historical attitude that can be aligned with the symbolic strategy of the PCI, as identified by Kertzer.

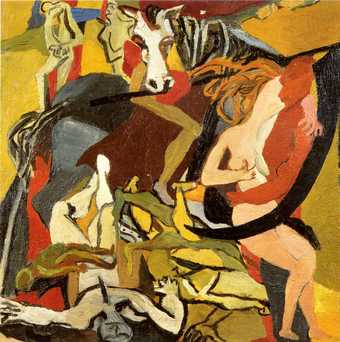

Fig.4

Renato Guttuso

Fucilazione in campagna (Execution in the Countryside) 1938

Oil on canvas

980 x 730 mm

National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome

© Renato Guttuso / DACS 2020

Guttuso’s major contribution to Art against Barbarism – Fucilazione in campagna (Execution in the Countryside) of 1938 (fig.4) – brought an already layered history to the exhibition’s comparative presentation of Rome’s cultural resistance.55 Reworking Goya’s Third of May, whose composition is here cropped and reversed, with a reduced cast of perpetrators and victims, Guttuso’s painting depicts an execution by gunshot at point-blank range, punctuated by bodies slumped on the blood-stained ground. In Goya’s tribute to the Spanish rebels, whose uprising against Napoleonic occupation we see brutally suppressed, Guttuso found the art historical framework through which to convey the historic nature of the present moment. He dedicated his canvas to the Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca, who is thought to have been killed by a Nationalist firing squad in August 1936, at the start of the Spanish Civil War.56 Exhibited in the Art against Barbarism show, Fucilazione in campagna thus brought the combined histories of the Napoleonic and Spanish Civil Wars into the communist construction of the Italian resistance.

Guttuso’s repeated allusions to Guernica – which he often deployed alongside other revolutionary models – in works that refer to the Italian situation can similarly be seen to perform Kertzer’s symbolic history-making in art historical terms: producing the Party’s own history through reference to episodes of world (art) history. This is not to imply that the works in question were directly commissioned by the Party to serve this purpose, but rather that Guttuso’s own historicism, formed in part during his first experiences of communism in the late fascist years, paralleled that of the Party. His formative experience of the PCI coincided with the years during which the Party’s symbolic strategy was being developed, making him a consumer of that symbolism as well as, through his artworks, a producer of it.

It is telling that the history-making capacity of art was explicitly recognised in the founding manifesto of the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti, the post-war successor to the Corrente group, which has itself been described as the artistic equivalent of the communist Garibaldi Brigades in the armed resistance.57 The brief manifesto, issued in Venice on 1 October 1946 and signed by eleven former members of Corrente, including Guttuso, closed with the emphatic declaration: ‘Art is not the conventional face of history, but history itself’.58 This, it might be argued, was the legacy of the cultural resistance, formed in opposition to fascism and informed by Guernica. Just as the PCI’s resistance narrative was foundational in constructing its post-war self-history, so the strategies that Guttuso had established in opposition to fascism became the foundation for his post-war art of opposition. Foremost among these was his use of Guernica.

Painting history, history painting

Fig.5

Renato Guttuso

Fuga dall’Etna (Flight from Etna) 1938–9

Oil on canvas

1440 x 2540 mm

National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome

© Renato Guttuso / DACS 2020

Guttuso’s initial, heavily coded recourse to Guernica occurred in his first major painting relating to the struggle against fascism, Fuga dall’Etna (Flight from Etna) of 1938–9 (fig.5), which adopts the erupting volcano as a probable metaphor for the violence of the regime.59 It was conceived and executed at a crucial moment in the history of European fascism, and Italy’s place within it. In May 1938, two months after the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany), Hitler undertook a state visit to Italy, appearing alongside Mussolini and amid much fanfare in Rome, Naples and Florence in a carefully choreographed performance of the Rome-Berlin Axis. In November that year Italy introduced racial laws that defined Italians as Aryans and enforced discrimination against those defined otherwise. In May 1939 the Pact of Steel was signed between Italy and Germany, which would lead to Italy entering the war against the Allies in June 1940.

While Fuga dall’Etna shares little with Guernica in stylistic terms, it borrows from Picasso’s iconography to describe domesticity disrupted by violent suffering. This is most evident in the bared teeth and strained necks of Guttuso’s horses, the distressed expressions of his cattle, and in the figures of naked women gesturing in despair. But Guernica is present too in the vernacular details of this scene. At the top left of Guttuso’s canvas, the terracotta roof tiles and half-open shuttered window recall similar architectural elements to the right of Guernica’s centre. In both paintings, the effect is to locate the scene of suffering in everyday domestic space. While Guttuso places his figures outdoors, the overturned rush-seated chair at the heart of his composition refers to the interior room space preferred by Picasso and, like the kitchen table to the right of the bull in the upper left part of Guernica, serves to highlight the shocking proximity of domesticity and death.

The figure at the heart of Guttuso’s composition is adapted from one of the iconic revolutionary paintings that would later be reworked for the Art against Barbarism exhibition: Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People. Like Delacroix’s prototype, Guttuso’s ‘Liberty’ is depicted in a light-coloured dress, with her breast exposed and her head turned over her right shoulder to face the crowd that follows. In place of Liberty’s tricolour, she carries a furled red flag in her right hand, making a necessarily more understated gesture of political allegiance, whose coding was sufficient to allow Guttuso to exhibit the painting at the officially sanctioned Premio Bergamo in 1940, where it was awarded third prize.60

Although Fuga dall’Etna’s dimensions (1440 x 2540 mm) do not match the mural-sized scale of Guernica (3490 x 7770 mm), its size signals Guttuso’s intention to make a contemporary history painting in the manner of Picasso. That he should make it for public exhibition at an art prize founded by the fascist Minister for National Education suggests that Guttuso sought to make the kind of cultural intervention of which Guernica was exemplary, thus fulfilling the didactic imperative of history painting. If, as Gramsci argued, Italy’s lack of national-popular culture could be attributed to its lack of popular revolution, Fuga dall’Etna might be seen as a precocious attempt to invent both. Guttuso’s inclusion of a figure indebted to Delacroix’s Liberty together with her white-jacketed male counterpart at bottom left, who beckons the suffering crowd to follow him, stages the natural disaster of the painting’s title as a popular uprising. In doing so, Guttuso imagines the premise for the emergence of Gramsci’s national-popular culture, and seeks to bring it about in the form of a history painting, after the model of Guernica.

The ‘practical’ Picasso

Fig.6

Renato Guttuso

Marsigliese Contadina (Peasant Marseillaise) 1947

Oil on paper mounted on canvas

1500 x 2020 mm

Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

© Renato Guttuso / DACS 2020

Guttuso would borrow from these same revolutionary prototypes almost a decade later in a painting relating to post-war peasant activism: Marsigliese contadina (Peasant Marseillaise) of 1947 (fig.6). Here, Guernica’s idiom and Delacriox’s iconography are combined with references to another revolutionary subject that had been reworked in the Art against Barbarism show: François Rude’s Arc de Triomphe frieze from 1833–6, La Marseillaise. Liberated from the constraints of working and exhibiting under fascism, and inspired by having met Picasso on his first visit to Paris in 1946, Guttuso’s citation of Guernica is now more explicit, his neo-cubist figuration and striking grisaille palette paying unmistakable homage to Picasso’s painting.61 But where Guernica’s dragging, twisted forms were inscribed with pain, as art critic John Berger observed, those of the Marsigliese contadina are shaped by the militant energy of La Marseillaise and Liberty.62

Guttuso’s compact, frieze-like composition alludes, like his title, to Rude’s sculptural group. At its centre is a striding female figure whose featureless face, turned boldly towards the viewer, invites an allegorical interpretation. Leading her group’s advance with a decisive forward stride and an outstretched, flag-bearing arm, she reveals her indebtedness to the warrior-like Liberty made iconic by Rude and Delacroix. Guttuso further signals her revolutionary ancestry in the red and blue colouring of the flag and sky – the most striking breaks in his grisaille palette – which combine with white accents to evoke the French tricolour that had been the symbolic focus of Delacroix’s composition and the revolution that inspired it.

The Marsigliese contadina was the major painting to emerge from Guttuso’s visit to his native Sicily in 1946 to observe at first hand the peasant land occupations taking place there. It was, in other words, an early product of his participation in what would become the andata al popolo, that key national-popular project of the PCI. Guttuso’s translation of post-war peasant activism into the language of Guernica invokes the anti-fascist resistance as a symbolic as well as historical precedent for the wave of land occupations that swept across rural Italy from the mid-1940s to the early 1950s. These occupations were sanctioned by government legislation, which permitted the takeover of uncultivated or poorly cultivated land, on the condition that the occupying peasants form production cooperatives.63 Like the resistance, the mobilisation of the peasant movements to occupy uncultivated land could be understood as a popular engagement with the nation. This was particularly significant given the concentration of land occupations in the south, which had not experienced the resistance proper. Land reform was a central issue in the PCI’s post-war programme for the south, where it sought to build consensus in the absence of the support base generated by the resistance in the north and centre of the country. As Guttuso’s work demonstrates, the symbolic weight of the land occupations was considerable. In alluding to Rude’s (armed) volunteers – who set out to defend the French Republic – in the language of Guernica, Guttuso casts his peasant protesters as defenders of resistance values in the newly republican Italy. This revolutionary palimpsest conforms to the historical framework constructed by the Italian Communist Party to produce its preferred reading of current events. Italy had become a republic following the constitutional referendum of 2 June 1946, in which 54.3% of votes were cast in favour of republicanism. However, the south, including Sicily, remained overwhelmingly monarchist.64 If Guttuso’s Sicilian peasants were revolutionary defenders of the resistance and the republic, they were certainly not representative of the wider communities they were meant to symbolise. This was rather a rallying call: art as agitprop, in the manner of Guernica.

The militancy of Guttuso’s peasant group was consistent with the symbolic world of the PCI, in which the military metaphor was an essential component. Post-war communist discourse, as Kertzer has argued, presented history as a continuing battle between good and evil, with the resistance struggle as its major point of reference.65 In his catalogue essay introducing Picasso’s solo show that occupied one room of the Italian Pavilion at the 1948 Venice Biennale,66 Guttuso situated the Spaniard’s work at the heart of a similarly dualistic struggle: ‘with his canvases, he enters … a debate that is no longer about abstract and concrete, or figurative and non-figurative, or formalism and naturalism, but between human and inhuman, between “good” and “evil”, no less.’67 Predictably, Guttuso traced this moral interpretation of Picasso’s work back to the fascist years in which his generation had first encountered it: ‘Perhaps precisely because of this climate [of fascism], the lesson of Picasso reached young Italian painters through a filter of tension and rage that allowed them to make profound use of it.’68 Encountered through the lens of fascism, Guttuso’s generation found, to borrow historian Hayden White’s terminology, a ‘practical’ Picasso. White’s notion of the ‘practical past’ is an ethical conception of history in which the past is put to work in the service of the present, as opposed to the ‘historical past’, a scientific conception of history in which the past is ostensibly studied for its own sake, and confined to the past.69 It was this ‘practical’ Picasso that Guttuso’s essay presented to the Italian public at the 1948 Biennale, in what was the first significant exhibition of Picasso’s work in Italy.

Organised by Rodolfo Pallucchini, the Secretary General of the Biennale, the exhibition comprised nineteen paintings from the private collections of Yvonne Zervos in Paris and Roberto Meier in Zurich.70 Made between 1907 and 1942, these works documented key phases in Picasso’s artistic development, from analytic and synthetic cubism, through surrealism, to the semi-abstract figurative paintings of the late 1930s and early 1940s. The latter included Night Fishing at Antibes 1939 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), Picasso’s largest and, according to the Italian press, ‘most important’ painting since Guernica.71 The show was neither entirely cohesive nor comprehensive, but it offered the Italian public its first chance to examine Picasso’s oeuvre, and Italian artists an unprecedented opportunity to situate their work within its orbit. As the first post-fascist Biennale, the 1948 exhibition was an occasion to take stock of the recent past and to consider how it might inform new artistic developments. Elsewhere in the Italian Pavilion, a two-room exhibition dedicated to the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti revealed Picasso’s influence on Guttuso’s generation.72 This was nowhere more the case than in Guttuso’s own work, which was dominated by the angular forms and flat space he had encountered through Picasso. Alongside these stylistic devices, Guttuso’s paintings in the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti display aligned themselves with the humanity he had identified in Picasso’s work. Focusing on worker subjects – including Lavandaia (Washerwoman) of 1947, Cucitrice con drappo rosso (Seamstress with Red Flag) of 1947, and Contadino siciliano (Sicilian Peasant) of 1948 – Guttuso applied the pictorial lessons of Picasso to a Gramscian project.73 Picasso had been, and would continue to be, cited and put to work.

This ‘practical’ engagement with Picasso, traced back, as Guttuso’s catalogue essay explains, to the fascist years in which it had begun, resonates with the historical attitude of the Italian Communist Party. As Kertzer puts it, the leadership of the PCI ‘worked tirelessly to construct its history … to define the party’s identity … and create a world in which current events could be properly interpreted.’74 In repeatedly citing the revolutionary art of the past, Guttuso, it seems, was equally committed to invoking the past in the service of the present. If the resistance was the touchstone for the PCI’s constructions of history, Guernica was Guttuso’s resistance.

Guttuso’s Guernica at war

Fig.7

Renato Guttuso

Massacro (Massacre) 1943

Oil on canvas

550 x 705 mm

Museo Novecento, Florence

© Renato Guttuso / DACS 2020

Fig.8

Renato Guttuso

Trionfo della morte (Triumph of Death) 1943

Oil on canvas

550 x 550 mm

National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome

© Renato Guttuso / DACS 2020

By the late 1940s Guernica was firmly established as the primary source for Guttuso’s art of protest. We have seen this already in Fuga dall’Etna, Guttuso’s first major anti-fascist painting and his first attempt to address the Italian situation in the language of Guernica. A number of other paintings of the late fascist years – including Massacro (Massacre) and Trionfo della morte (Triumph of Death) , both from 1943 (figs.7 and 8) – are heavily dependent on the universalising iconography that has made Picasso’s Guernica so quotable.75 Both artists present naked corpses of statue-like men, contorted horses and weeping women to describe a timeless state of brutality and despair, which, contextually and by association, evoke the particular circumstances of Italy and Spain. Guttuso’s citation of Guernica in these scenes of unrelenting mortality speak of his desperation during what would be Mussolini’s last year in power, and a time of acute personal risk. Finding himself under political surveillance, Guttuso left Rome in the summer of 1943 to take refuge with the collector Alberto della Ragione in Quarto, outside Genoa.76 Although Massacro and Trionfo della morte were executed in early 1943 – some months before Italy’s resistance movement began that September in the wake of the deposition of Mussolini and Italy’s alignment with the Allies – both paintings belong firmly to the artistic resistance that anticipated the armed equivalent to come. They are the painterly expression of Guttuso’s carrying of his Guernica postcard as an ideal membership card, which persisted until this very year.

Both Massacro and Trionfo della morte include specific citations from Guernica. The figure of the grieving woman in the upper right segment of Massacro enters the scene through a window, open-mouthed in despair, much like the candle-bearing figure of Guernica, whose dark, wavy, grey-flecked hair she shares. The outstretched arm and open-palmed hand of Guttuso’s figure are borrowed from another of Guernica’s grieving women: the mother who screams in agony at her baby’s limp body. Like Guernica’s mother, the grieving woman of Massacro gestures in despair at the devastation before her, the deeply etched lines of her upturned palm imploring us too to bear witness. In Trionfo della morte, Guernica’s horse provides the major iconographic model. On the left side of the painting, the hindquarters of Guttuso’s horse, like those of Picasso’s, are viewed side-on and tilted towards the viewer. Its neck is twisted back over its body, and in the lower centre the horseshoe of an upturned hoof reveals itself, after Picasso’s precedent, among the bodies on the ground. But there are differences too: in place of Guernica’s horse-as-victim, Guttuso’s horse is the mount of Death. Its head turns to confront the viewer, but does not cry out in pain, as Picasso’s does; rather, its nose rests upon the handle of the scythe poised to claim Death’s latest victims.

Fig.9

Unknown artist

Trionfo della morte (The Triumph of Death) c.1446 from the court of Palazzo Sclafani, Palermo

Fresco

6000 x 6420 mm

Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo

Fig.10

Renato Guttuso

Natura morta con lampada (Still Life with Lamp) 1940–1

Oil on canvas

550 x 800 mm

Galleria d’Arte Maggiore, Bologna

© Renato Guttuso / DACS 2020

Guttuso’s horse, as his title implies, is a hybrid. It is Guernica’s horse haunted by the skeletal animal ridden by Death in the fifteenth-century Trionfo della morte fresco from Palazzo Sclafani in Palermo, close to Guttuso’s native Bagheria (fig.9). This too was a painting that Guttuso had understood in relation to Guernica. Writing in Il Selvaggio in April 1940, three months after he received Brandi’s postcard from New York, Guttuso made a direct connection between this painting and Guernica:

Observing a large panel by Picasso, I think back to the Trionfo della morte at Palazzo Sclafani in Palermo … In the Palermo encaustic, there is the medieval sense of equality in the face of death, old age, youth, the poor and the powerful; in Picasso’s painting, there is a modern sort of terror and tragedy, without resignation, under the light of electric lamps.77

While the oppressive political circumstances of spring 1940 prevented him from naming Guernica, Guttuso’s mention of ‘electric lamps’ leaves an unmistakable clue for readers familiar with Picasso’s work. He would express this same clue pictorially in a still life of that year, Natura morta con lampada (Still Life with Lamp) (fig.10), which features the black shade of an electric light hanging ominously over a table. The homage to Guernica’s electric lamp is reinforced by the painting’s alternative title, Natura morta con bucranio e lampada (Still Life with Ox Skull and Lamp), which directs our gaze towards the ox skull beneath it. In place of Picasso’s living, suffering bull and jaggedly illuminated electric lamp, Guttuso gives us that animal’s brittle remains and a spent, blackened bulb to suggest a Guernica post-mortem.78 These motifs are combined with a birdcage and a red cloth backdrop to suggest politically motivated oppression: a comment, surely, on the political experience of the outlawed party Guttuso had joined in the year he made this painting, the year of Italy’s entry into the Second World War. These implied meanings would be made more explicit after the war, when the painting was reproduced, in colour, in the founding issue of Il ’45 in February 1946, alongside Morlotti’s ‘Letter to Picasso’.79 Here, as we have seen, Morlotti attributed to Guernica a revitalising effect, a renewed desire ‘to live, to leave prison, to believe in painting and in ourselves’.80 In this shared context of publication, Guttuso’s painting might be understood as the pictorial equivalent of Morlotti’s statement. Guttuso’s overturning of a birdcage and hanging of a flag-red cloth suggest a rejection of entrapment and an embracing of belief, while the Guernica-inspired motifs indicate the cause of those effects in a painting made at the end of the year in which Guttuso had received Brandi’s postcard of Picasso’s mural.81

Fig.11

Renato Guttuso

Crocifissione (Crucifixion) 1940–1

Oil on canvas

2000 x 2000 mm

National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome

© Renato Guttuso / DACS 2020

Although Natura morta con lampada codes its references to Guernica through the memento mori conventions of still life, this triumph of death in the domestic domain speaks directly to the room space of Picasso’s painting. In placing Guernica’s kitchen table centre stage, Guttuso underlines Picasso’s point that death, in wartime, finds its victims at home. It belongs to a series of fraught still lifes executed by Guttuso in the early 1940s, alongside his major protest painting of the period, Crocifissione (Crucifixion) 1940–1 (fig.11), which likewise codes contemporary political commentary in the language of art historical tradition.82 Guttuso’s initial ideas for this painting, recorded in a diary entry of October 1940, had placed the crucifixion scene in an interior, after the model of Guernica: ‘I want to paint Christ’s execution as a scene of today as a symbol of all those who suffer affront, jail, torture, because of their ideas … crosses (gallows) raised in a room. Soldiers and dogs – dishevelled, half-dressed, crying women – in the light of a candle (Guernica’s candle?).’83 The only legacy of this idea of domestic crucifixion in the external setting seen in the final painting is the still life composed of instruments of torture, incongruously placed on a kitchen table in the immediate foreground of the composition. By his own admission, Guttuso ‘did not have the courage’ in 1941 to realise his initial plan to show the crucifixion as a contemporary scene ‘in an interior, just as our executions occur today … with a gunshot to the nape of the neck’.84

Fig.12

Renato Guttuso

Gott mit Uns 1944

India ink on paper

Published in Renato Guttuso, Gott mit Uns, Rome 1945

© Renato Guttuso / DACS 2020

Guttuso’s initial idea for updating the iconography of the crucifixion would subsequently be realised during the Nazi occupation of Rome, when scenes of contemporary brutality came to dominate his work. This was nowhere more evident than in Gott mit Uns (God with Us) of 1944, an emphatically non-allegorical series of drawings of Nazi atrocities committed on Italian soil.85 One of these scenes of execution shows civilian victims herded into an interior by uniformed and armed German soldiers (fig.12). The room itself recalls the interior of Guernica in the clearly delineated room space, grid of floor tiles and electric ceiling lamp hanging left of centre. The bowed heads of the prisoners and the pistol held, trigger-ready, by the soldier at far right anticipate precisely that contemporary mode of execution Guttuso had privately imagined during his work on Crocifissione. Begun during Guttuso’s Ligurian exile and completed following his return to Rome in 1944, when he would join the resistance, these drawings were made using inks from the clandestine press with which he was involved and were therefore materially as well as thematically bound to partisan activity.86

The series was shown (in part) at the Art against Barbarism exhibition in Rome in 1944, which, as we have seen, sought to establish a model for a national-popular culture informed by existing models from other national contexts, and to produce the history of Italy’s ongoing resistance through international histories of revolution.87 At the start of 1945, ahead of Italy’s liberation in April, the portfolio was published as an artists’ book by Galleria La Margherita in Rome, which would host an exhibition of the full set of drawings in August that year.88 Leaving behind the coded messages of paintings made for public exhibition during the fascist regime, the Gott mit Uns series made an explicit intervention into the public narratives of resistance and liberation. In this sense, as well as in its iconographic citations, it followed Guernica’s model of art as agitprop.

From World War to Cold War

The prevalence of Guernica in Guttuso’s wartime production secured its place within an Italian discourse of anti-fascism, into which the art of revolutionary France had, to a lesser extent, also been incorporated. As such, by the time he returned to Guernica – alongside Liberty Leading the People and La Marseillaise – for the Marsigliese contadina in 1947, Guttuso was situating post-war peasant activism within an established narrative of Italian resistance, which had itself been integrated, visually and symbolically, into broader European revolutionary narratives. In so doing, he produced, in art historical terms, the preferred historical narrative of the post-war PCI, in which the resistance – and the communist contribution to it – was the major frame of reference through which current events were understood.89 Guernica, then, was central to Guttuso’s production of communist history. By redirecting his preferred model of anti-fascist resistance towards an art of peasant protest, he fulfilled, by way of Guernica, the Gramscian prediction Trombadori had made in his review of Art against Barbarism in 1944: that the ‘popular and progressive’ content of the exhibited works could not ‘but serve and arise from the working-class movement on the path to progress’.90

If Guttuso’s land-occupying peasants in the Marsigliese contadina were aligned with the partisans, those against whom they exercised their agency were, by implication, aligned with the fascists. It was an idea that was beginning to gain traction by 1947, as the anti-fascist unity of the immediate post-war years gave way to Cold War sectarianism. In May that year, communist ministers were ejected from the government of the Christian Democrat Prime Minister Alcide de Gasperi, paving the way for the comprehensive victory of his party in the general election of April 1948. The militant and upbeat mood of Guttuso’s Marsigliese contadina, which seems to turn Guernica’s trauma into revolutionary euphoria, reflects the optimism of the Italian left ahead of that election, which was still looked to as the moment in which parliamentary majority would be achieved and the ideals of the resistance would come to power. Yet in his invocation of La Marseillaise, Guttuso reminds us that those ideals were in need of defence.

Given his acute historical and art-historical awareness, it also seems likely that by returning so emphatically to Guernica in 1947, Guttuso meant to mark the tenth anniversary of the making of Picasso’s mural and the atrocities that inspired it. Once again, this commemorative gesture is consistent with what Kertzer identifies as the PCI’s ritualistic engagement with history. Used ‘to create history and nourish the party’s symbolic universe’, anniversaries were an important means of legitimising ‘the party and its actions and leadership in the present’.91 This marking of ritual time as a means of asserting authority had been practised extensively by the fascist regime.92 In marking the passage of time with their own symbolic dates, the Italian communists engaged in an act of re-appropriation – of the nation and this temporal means of defining it – from fascism, with resistance history as the structuring narrative.

The commemorative temporality of Marsigliese contadina might also be extended to the tenth anniversary of the death of Gramsci, thus intersecting with the Party’s practice of worshipping individuals, as well as of ritualised time.93 A key component of the symbolic world of the PCI was the sacralisation of party leaders, none more so than the martyred Gramsci, who would become ‘the party’s leading visual icon’.94 As we have seen, this iconic treatment of his photograph is evident from its placement on Guttuso’s studio wall at Villa Massimo; and as the photograph of this studio shows, it was a status shared, in Guttuso’s imagination, by Guernica. Beyond the veneration of icons, viewing Marsigliese contadina as a (doubly) commemorative painting might also allow us to see it as the product of a Gramscian mode of engagement, after the model of Guernica. As an artistic representation of the popular struggles Guttuso had witnessed at first hand, the painting can be seen as an attempt to bridge the gap between the intellectuals and the people in the manner Gramsci had envisaged in his concept of the national-popular. That Guttuso should do so in the language of Guernica, on the tenth anniversary of its making and of Gramsci’s death, invites an association of Guernica with Gramsci that anticipates the curation of his studio wall.

Fig.13

Renato Guttuso

Portella della Ginestra 1953

Oil on paper mounted on canvas

1050 x 2000 mm

Private collection

© Renato Guttuso / DACS 2020

Guttuso’s return to the model of Guernica in the year of Italy’s second post-war general election also had a strong commemorative function. In Portella della Ginestra of 1953 (fig.13), Guttuso revisited an infamous scene of massacre pertaining to the peasant activism of the previous decade. On 1 May 1947, eleven peasants were killed by machine gun fire as they gathered to celebrate Labour Day at Portella della Ginestra in the province of Palermo. While the material responsibility for the massacre was that of the gang led by the infamous bandit Salvatore Giuliano, it is thought that a higher authority may have been behind the actions of the gunmen, with the mafia, the police and centre-right political parties all coming under suspicion.95 Like Picasso, Guttuso chose not to represent the perpetrators of his massacre, focusing instead on the distress of the victims, described in gestures of grief and sprawling bodies crushed beneath writhing horses. These recall the tangled compositions of those Guernica-inspired death scenes from Guttuso’s wartime oeuvre, Massacro and Trionfo della morte, though now articulated in a didactic realist style that cites Picasso’s iconography rather than his idiom.

The stylistic shift from Marsigliese contadina to Portella della Ginestra exemplifies Guttuso’s pragmatic response to Togliatti’s calling to order of communist artists in late 1948. Writing in the left-wing literary magazine Nuovi Argomenti in May–June 1953, Guttuso, who had been elected to the Central Committee of the Italian Communist Party in 1951, defended realism as the necessary mode of socially engaged art making for communist artists:

For us today this means reclaiming the most elementary means of figurative expression in order to represent a reality that is clear and recognisable to all, and to express that reality in the most complete way … Only by expressing reality as a whole … can one contribute to its improvement, enlighten men and raise awareness. Marxist ideology teaches us to adopt the most just point of view from which to face reality, to become acquainted with it and to express it, the point of view of the most progressive forces in society: the working class and its allies.96

While he prioritised the party’s national-popular project over artistic freedom, Guernica remained relevant to Guttuso because he understood Picasso’s lesson to be moral rather than formal. Recalling, in the 1960s, the impact of the postcard Brandi had sent to him in 1940, Guttuso explains that ‘Guernica was a key (not a dictionary)’.97 If Guernica was a guide – a model of artistic engagement that showed Guttuso’s generation a way forward – then its lessons might just as easily be followed by a painting like Portella della Ginestra. It is perhaps this social realist reinterpretation that produces the most Gramscian Guernica, the most national-popular Picasso.

In an essay published in the spring of 1952, Guttuso discussed the emerging realist movement, of which he was de facto leader, outlining a tactical approach consistent with his definition of Guernica as guide: ‘Today we can only say that there is a tendency, a group of artists that has set off on the path of realism, and that that realism is for us “a guide to action”, a condition for working, not a formula or a school.’98 Having invoked the oft-repeated statement that Marxism ‘is not a dogma, but a guide to action’,99 Guttuso went on to align the development of the realist movement with Gramsci’s position on the necessary conditions for the emergence of a new art, which could, he argued, only emerge from a new culture: ‘For us, the search for a means of expression is above all connected to a moral clarification, to the aspiration for a new culture “that cannot but be intimately connected to a new intuition of life, until it becomes a new way of feeling and seeing reality” as Gramsci said.’100 If Guernica, like realism, was for Guttuso ‘a guide to action’ for a means of artistic expression that would emerge, as Gramsci suggested, from a new moral engagement with life, then Portella della Ginestra can be seen as an example of the action guided by Guernica, the product of a moral engagement with contemporary reality.

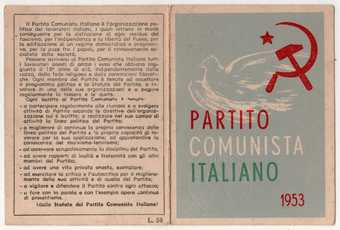

Fig.14

Membership card of the Italian Communist Party, 1953

Fig.15

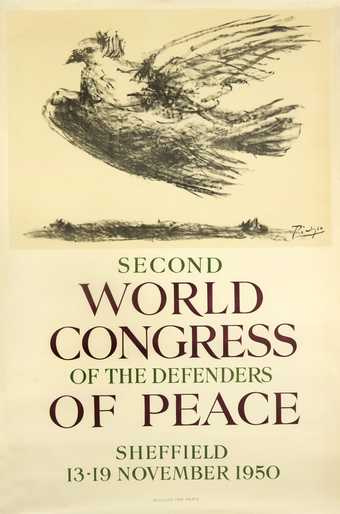

Poster for the Second World Peace Congress, Sheffield, November 1950, featuring Pablo Picasso’s Dove in Flight

In resurrecting the peasant killings of 1947 in this general election year, 1953, using the most iconic model of anti-fascist protest, Guttuso made a powerful statement about the era of Christian Democracy, which was consistent with the PCI’s election campaign theme of peace and cultural freedom. Emblematic of this theme was the design for that year’s party membership card (fig.14), which featured a pared-down version of the Dove in Flight lithograph that Picasso had produced for the poster for the Second World Peace Congress in Sheffield in November 1950 (fig.15). On the cover of the membership card, the outstretched wings of the dove connect the bold red hammer and sickle of international communism with the name of the Italian party, rendered in tricolour type. Here, the dove becomes a visual device linking the PCI’s international allegiance with its domestic concerns. In 1950 Moscow had declared the fight for peace to be the primary concern of communists worldwide,101 and it was towards this theme that the PCI directed much of its propaganda in the wake of its defeat in the general election of 1948.102

That it was the dove rather than Guernica that eventually made Picasso membership-card material is consistent with the use the Party found for his work in the context of the Peace Movement. The founding meeting of the Movement had taken place in Wroclaw, Poland in August 1948, under the title of Congrès Mondial des Intellectuels pour la Paix. Ostensibly an independent initiative of Polish and French intellectuals, the congress attracted an international community of artists, writers and academics.103 Picasso, in a major coup for the organisers, attended as a member of the French delegation, and Guttuso as a member of the Italian one.104 In reality, the congress had been planned by the Soviets under Andrei Zhdanov, secretary of the Soviet Central Committee and creator of the Party’s strict code for cultural production, which demanded absolute conformity from artists and intellectuals.105 These demands for cultural orthodoxy would surface over the course of the congress, with the Soviet writer Alexander Fadeyev launching a diatribe against western intellectuals and ‘formalism’ in art. Already indignant at this attack, Picasso would also be privately reprimanded for the decadent and bourgeois nature of his work.106

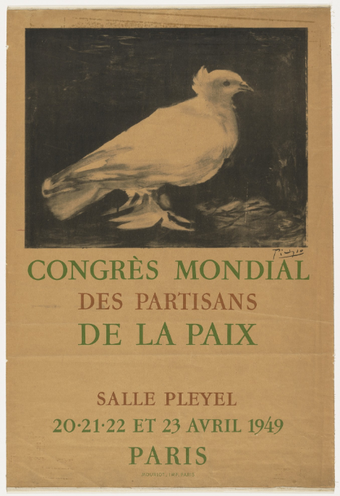

Fig.16

Poster for the World Peace Congress, Paris, April 1949, featuring a lithograph of a pigeon by Pablo Picasso

The second meeting of the Peace Movement, the first World Peace Congress, was held in Paris in April 1949 and offered a solution to the Picasso problem. The poet Louis Aragon, by this time the preeminent intellectual of the French Communist Party and an advocate of socialist realism, selected as the poster image for the Paris Congress Picasso’s lithograph of a pigeon, which he took to be a dove (fig.16). The subtle naturalism of Picasso’s pigeon was uncharacteristic of his work at this time, but offered Aragon an opportunity to find a form of Picasso’s art that was acceptable to international communism. At the same time, the status of its author, which was asserted in the prominence of Picasso’s signature on the poster, also allowed the pigeon to represent an independent avant-garde operating outside the prescriptive dogma of socialist realism, thus giving the campaign for peace increased credibility among non-communists, whose support was sought for the consensus-building agenda of the campaign. Through the success of Picasso’s Paris poster image, followed by his prolific production for subsequent propaganda materials, the dove became inextricably linked with the Peace Movement’s highly partisan campaigns against American military aggression and nuclear armament.107 These intensified following the outbreak of war in Korea in June 1950, three months after the US State Department had denounced the Peace Movement as ‘the leading Communist front organisation in the world’.108

The PCI’s use of Picasso’s dove on its membership card in 1953 can therefore be understood as a loaded Cold War statement. By this time, the targets of the Peace Movement – the perceived aggression and expansionism of the US – were moving closer to home. Italy’s entry into NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization) in 1949 triggered a process of re-militarisation: American and NATO bases appeared throughout the peninsula; the Italian military was hurriedly re-armed at American expense; and the Christian Democrat government repaid the investment by increasing the defence budget and extending the period of compulsory military service.109 Parallel to this, in the wake of the riots following Togliatti’s attempted assassination, was the expansion of the police force to include militarised mobile battalions in addition to brutally uncompromising flying squads.110 Juxtaposed with the strongest communist party in Western Europe, the repressive apparatus of the Christian Democrat state, coupled with a very visible US presence, set the scene for the playing out of Cold War conflicts on the domestic stage.

It was in this oppressive climate that the second edition of L’arte contro le barbarie (Art against Barbarism) was organised at the Galleria di Roma. Planned as a protest against the visit of US President Eisenhower to Italy in January 1951, the exhibition deliberately invoked the Nazi barbarity that the first exhibition of this title had protested against in 1945.111 Eisenhower’s visit gave Italian communist intellectuals the opportunity to rehearse the partisan rhetoric of the Peace Movement, equating American military aggression with Nazi warmongering.

Participating artists in the second Art against Barbarism exhibition were unrestrained in their visual statements of anti-Americanism. Guttuso’s contribution, Sogno di un guerrafondaio (Dream of a Warmonger) (private collection), is dated 17 January 1951, the day before the exhibition was due to open. It shows a caricatured President Eisenhower carrying lambs to their slaughter, assisted in his massacre of the innocents by a shepherd with the exaggerated features of Prime Minister de Gasperi. However, the doors of the Galleria di Roma would not be opened to the public. Rome’s Chief of Police intervened to prevent its inauguration, citing the expiry of the gallery’s licence.112 The police also had the works inspected by an official from the Ministry of Education, who dismissed the artistic value of the exhibition and therefore any need for public access to it. In early February the show was moved to a private venue, the communist Casa della Cultura. By this time Eisenhower’s Italian visit was over, but far from relaxing its grip, the police reaction was even more extreme: at the time of its scheduled inauguration on the afternoon of 5 February, around one hundred armed officers were dispatched to set up road blocks around the venue, accompanied by a police commissioner who declared the exhibition unlawful.113 Lest there be any doubt as to the motives for the police intervention, Guttuso and some of the other artists were referred to the judicial authorities for the offence of ‘vilipendio al Governo’ (‘public defamation of the Government’) and engaging in ‘atti ostili idonei a turbare le relazioni con uno stato estero’ (‘hostile acts fit to upset relations with a foreign state’).114

Fears of a Christian Democrat dictatorship in Italy were raised in 1952 when the ruling party, shaken by its poor performance in the recent local elections, proposed an unconstitutional electoral reform law that would give two thirds of seats in the Chamber of Deputies to any coalition polling more than 50% of the vote in a national election.115 The communists and socialists bitterly but unsuccessfully contested the law, which they renamed ‘la legge truffa’ (‘the swindle law’), comparing it to Mussolini’s 1923 Acerbo law that awarded two thirds of seats to any party gaining over 25% of the vote.116 The Christian Democrats assembled a seemingly failsafe coalition with the Liberals, Social Democrats and Republicans, a grouping that had collectively polled 62.6% of votes in 1948.117 The general election of 1953 therefore assumed historic importance, with the left fighting against parliamentary marginalisation and the Christian Democrat centre-right seeking to extend their power by unconstitutional means. It was also to be an election characterised by the wider conflicts of the Cold War. Clare Boothe Luce, American Ambassador to Italy, threatened serious repercussions in the event of a Christian Democrat defeat, while the Italian left expected the same in the event of a Christian Democrat victory.118

Exhibiting Picasso

In entering this election year under the banner of Picasso’s dove, the PCI placed the artist at the forefront of these conflicts. He would take on an even greater electoral role with the staging of a major retrospective of his work in Rome and Milan in 1953, the former opening at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna on 5 May, just over a month before polling day on 7 June. While the art critic and historian Lionello Venturi presided over the final stages of the exhibition’s organisation at the Galleria Nazionale, the retrospective had been a PCI initiative. The communist senator Eugenio Reale first wrote to Picasso to propose the exhibition in August 1952, and would visit him to confirm plans in December that year.119 Reale did not hide the electoral function of the exhibition from Picasso, who lent his support to the project as a political enterprise.120 That he personally selected the works to be exhibited – almost 250 in total, spanning thirty years of his career – is evidence of his cooperation with the project.121

In the event, the exhibition would take on an important strategic function for Picasso too, providing an opportunity for rehabilitation in the wake of the row that followed the publication of his drawing of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in Les Lettres françaises on 12 March 1953.122 Intended to commemorate Stalin following his death on 5 March, the portrait provoked widespread outrage within the French Communist Party, its heavy lines and stylised features deemed unworthy of the leader. The ensuing scandal reverberated throughout the French Communist Party and cast doubt on Picasso’s political commitment.123 The opening of his retrospective as part of the Italian Party’s election campaign less than two months later provided a means for him to reaffirm his allegiance. By maintaining its own commitment to the exhibition, the PCI, for its part, was able to emphasise its independence from Moscow, and from the more repressive cultural climate that had surfaced in the French Party.

The electoral power of Picasso was not lost on the Christian Democrats. In February 1953, the Christian Democrat senator Mario Cingolani wrote to Palma Bucarelli, Director of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, to suggest that the exhibition be postponed until such a time as ‘we are beyond these tempestuous times in Parliament!’.124 While the exhibition went ahead as planned during the pre-electoral period, the government sought to limit its political impact by prohibiting the display of Picasso’s most topical and anti-American painting, Massacre in Korea 1951 (Musée Picasso, Paris).125 Confined to the stores of the Galleria Nazionale, and omitted from the official catalogue, it was left to the communist press to bring Picasso’s painting, and the government censorship of it, to public attention. In an article published in L’Unità on 3 June 1953, Guttuso, himself a member of the exhibition’s Executive Committee, launched a scathing attack on the Christian Democrats’ intervention, directing much of his anger towards Giulio Andreotti, who had established a reputation for obstructing left-wing culture as Undersecretary for the Press, Entertainment and Tourism:

The Honourable Andreotti also knows that this show should have exhibited one of the masterpieces of the great Spanish artist: Massacre in Korea. And that this painting has not been exhibited on account of an unofficial but peremptory veto … This painting has already been exhibited in France, in an official salon; it has been published by newspapers and magazines all over the world: only in Italy could it not be exhibited. This shows that the guiding principle of Christian Democrat cultural politics, the principle of reactionary censorship, has been defeated only in part.126

Published four days before the election, Guttuso’s article was entirely on message according to the electoral strategy of the PCI: the exhibition’s success demonstrated support for progressive culture across broad swathes of the Italian public, and the reactionary interventions of the Government demonstrated that this culture was in need of defence. In response to the repressive climate produced by increased government censorship, the Cultural Commission of the PCI, in its resolution of April 1952, had adopted an electoral alliance strategy to build consensus around the idea of cultural freedom.127 In Picasso they found the ideal figure around whom supporters of progressive culture could coalesce, across artistic and political boundaries. Equally famed for his communism and his unorthodoxy, Picasso could stand at once for political engagement and modernist experimentation. These alternative interpretations were evident in the literature produced for the Roman exhibition, which presented competing claims for his work. The official catalogue, edited by Venturi, was sold at the Galleria Nazionale alongside a special double issue of Realismo, which was presented to the public as a more affordable alternative, complete with its own exhibition guide.128 That a journal whose editorial board was composed of the Communist Party’s foremost cultural cadres was offered for sale in a state institution is testament to the decisive role of the PCI in organising the exhibition.129

Unsuprisingly, Realismo proposed a reading of Picasso that privileged content over form. Guttuso’s open letter to Picasso, with which the special issue began, set the tone: ‘What matters to us most of all is that which you have said and suggested to us with your work … What matters to us is that which lies beneath your formal audacities’.130 In the official catalogue, meanwhile, Venturi sought to distance Picasso’s artistic expression from reality, even in the case of his most politically engaged works: ‘Guernica expresses the horror of human cruelty, the agony of Picasso’s vision, but it does not depict the event of the destruction of a holy city. That is to say that there is a complete translation from historical reality to fantastical vision, whatever the agony.’131

For Realismo, whose cultural project was situated within a narrative of continuity from anti-fascism to post-war realism, Guernica was placed at the heart of his oeuvre, despite its absence from the exhibition itself, in order to produce the journal’s preferred reading of Picasso. Mario de Micheli’s essay traced the realist reception of Picasso’s work in Italy through Guernica, highlighting its enduring impact on the resistance generation: ‘its discovery nourished us for years and years, spurred us to heroism, taught us to make of art a weapon in the service of man.’132 Antonello Trombadori dedicated a section of his article to Guernica, attributing its ‘historical importance’ to its ideological basis, overcoming ‘almost a century’ of ‘political indifference’ in western art.133 Roberto Battaglia’s exhibition guide included a separate entry for Guernica, as if to ensure its vicarious presence, while also noting the weight of its absence.134

Fig.17

Poster for the exhibition Mostra di Picasso at Palazzo Reale, Milan, 1953, featuring a reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica