David Bomberg (1890–1957) left two legacies: as a pugnacious, experimental painter, and as one the most influential teachers in the post-Second World War period. In the latter role, he inspired a particular artistic identity within generations of art students, some of whom, including Frank Auerbach and Gustav Metzger, have become well known. These dual legacies sit uneasily with one another, largely because Bomberg’s parallel activities of teaching and painting during the later part of his career (c.1948–1957) have been treated as oppositional, leading observers, critics and art historians to ignore how each affected the other.

The importance of Bomberg’s teaching was clear to critics in the post-Second World War British art scene. David Sylvester wrote in 1960 that ‘the most serious new trend in painting to have appeared in this country since the war is that which has been inspired by the example of David Bomberg’.1 John Berger wrote in 1959 of Bomberg and his students that ‘someone will soon give this movement a name and then people will be able to talk about it.’2 John Russell, another notable critic, called it an ‘undeterredley active underground’ in 1962.3

There is a familiar saying, representative of a wider attitude: ‘those who can’t do, teach’. In 1958 the artist Robert Lowe dryly lamented the prevalent notion of the artist who teaches:

His life becomes a series of compromises between the demands of these two masters. It becomes a life of continual meditation and arbitration in which neither master is served with the total commitment and dedication, which he deserves. The only possible resolution to such a life, based as it is on an unholy marriage of vocations, is the ultimate triumph of one master and the death of the other.4

The divide between these two occupations (ideally, vocations) was one widely acknowledged in the mid-twentieth century, as artist George Szekely noted in an article of 1978 when an angry letter answered his requests for graduate school programme descriptions, telling him to clarify from the outset whether, in his words, he wanted ‘to be an artist or an art teacher’.5 As the effects of art education reform and the number of universities greatly increased in the 1970s and 1980s, more and more artists, including Lowe and Szekely, welcomed the full creative potential of allowing artistic growth and teaching to nourish each other – a transition that art education journals of the time attest.6 Ground won by artist-teachers within art education, however, has not been matched within art history.

Bomberg’s renown was hard won by his family and followers, and in their battle for recognition, his teaching was often an inconvenient success.7 Despite Bomberg’s posthumous popularity among the rising generation of art students, institutional recognition was harder to win: the Arts Council memorial exhibition of 1958, which was the first serious exhibition of work from across his career, was not developed into a thorough retrospective until 1988.8 After the early 1920s, during which the institution purchased two of his drawings, Tate did not acquire any works by Bomberg until the 1960s – and until the end of that decade, these were all pieces from his early career.9 In large part this responded to Bomberg’s work remaining largely unsold and un-exhibited during his final years.10 It also derived from a lack of appreciation for the continuity in his practice. His three main periods were difficult to reconcile, from his early success with mechanised forms and solid, hard-edged colours to his experiments with the lugubrious naturalism of his Palestine landscapes, to the impasto immediacy of his later interpretative portraits and landscapes. Bomberg’s later works appeared discontinuous from his early ambitions, and he suffered critical neglect that shook his confidence and destabilised his living conditions.11 He was not a ‘success’ in the market terms used to evaluate an artist during his lifetime.12 It was, in fact, the championing of his teaching by outspoken students that threatened to eclipse his legacy as an artist, as expressed by art historian Simon Watney in 1987: ‘Bomberg was undoubtedly a great teacher. It does not however follow that great teachers are always great artists.’13 Even the long-time collector of Bomberg’s work Arthur Stambois wrote to Bomberg in 1945 in the same vein:

I was very pleased to notice a great change in your views on life and can never remember seeing you look so pleased with life as you did the other night – it seems that teaching has brought you peace of mind and satisfaction to your spirit … you will shortly reach your true zenith which lies in your power to pass on your very fine knowledge to the initiated and also the unsophisticated – as David I think that will be your truer vocation.14

The notion of teaching being Bomberg’s ‘truer vocation’ spurred his widow, Lilian Holt, to regard his teaching as a lamentable distraction.15 Teaching is often underplayed in art historical works on Bomberg, including those of his most prominent biographer, Richard Cork.16 This is particularly unfortunate as it is Cork’s monumental monograph on Bomberg that contains the most thorough account of Bomberg’s teaching activities written by a non-student – relatively few published words have been dedicated to Bomberg-the-teacher, fewer still pushing past mere documentation, which greatly contrasts with the voluminous work addressing Bomberg-the-artist.17 Aside from Cork, the most extensive writer on Bomberg’s teachings is a former student, Roy Oxlade. He diligently transcribed and analysed Bomberg’s scrawled and fragmentary archive, collating it with his own experiences of Bomberg’s teaching in two postgraduate theses and in a special issue of the RCA Papers.18 Despite some excellent insights, Oxlade lacks distance: he elides facts about the student community and reads Bomberg’s career from the pseudo-mystical position of Bomberg’s late self-styling.19 Both Oxlade and Cork provide much information on the teaching imparted to the students, but they underplay or ignore the effects of Bomberg’s teaching on his artistic practice. Bomberg’s archive at Tate preserves evidence of how transformative his teaching was – both as a practice and as a conceptual activity in his later career.20

The educational theorists Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger’s idea of ‘communities of practice’ states that ‘learning involves the whole person; it implies not only a relation to specific activities, but a relation to social communities – it implies becoming a full participant, a member, a kind of person’.21 It is important to consider not only how and what Bomberg taught but also how his was a ‘community of practice’. This stands in contrast to Cork and Oxlade, who seek to endorse the greatness of Bomberg-the-artist by characterising his teaching as either an interruption (Cork) or as a symptom of artistic greatness (Oxlade). I would like to reclaim Bomberg’s teaching period and offer a detailed look at it, making use of both archival material and testimony from former students. In the sections that follow, I argue that the practice of his teaching – and its reliance on conditioning a set of relations to a social community that resulted in two artist collectives, the Borough Group and the Borough Bottega – was, contrary to the dominant narrative, beneficial for Bomberg’s art and that his late work deserves reappraisal. Bomberg’s teaching should not be separated from his interest across his later career for an organic, human engagement, not only through his aesthetics and personal practice but also from his communal participation.

The class structure and students

Fig.1

David Bomberg

The Round Church, Middle Temple 1944

Private collection

© The estate of David Bomberg

Bomberg was in his mid-50s when he began steady teaching, and when he did it was with difficulty and out of economic necessity.22 Once he did, however, he poured tremendous energy into the endeavour, crafting a radical community from scant materials and attracting a loyal following of students and admirers that became a cultish sub-culture in the post-war period. Bomberg sought a teaching position for years before the human resource drain of the Second World War provided him with his first substantial positions: Oxlade records that between 1939 and 1944 Bomberg submitted applications for more than 300 teaching positions and though he was rewarded with occasional evening classes from 1937 onwards, they were precarious, free-form and no-growth positions.23 Bomberg’s first significant break came via architect and educator Charles Riley, who recommended Bomberg to the Bartlett School of Architecture in 1944 as a drawing teacher. In this, Riley acutely perceived the benefits of exposing aspiring architects to Bomberg’s sense of mass and structure, exemplified by his charcoal drawings of St Paul’s Cathedral and the Inner Temple Round Church, London in 1944–5 (fig.1).24 It was, however, the Borough Polytechnic in 1945 – where he was allotted a repurposed engineering room for two days a week, though by 1947 this was cut to one day – that allowed Bomberg the freest scope to develop his teaching practice.25 He remained there, teaching day and evening classes, for eight years.26

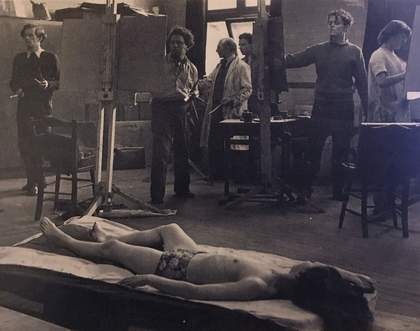

Fig.2

David Bomberg (centre) with students at Borough Polytechnic, c.1946–50

It is to Bomberg’s credit that although he was unable to win a secure position, he managed to use the bureaucratic informality of the Borough to his advantage, crafting a class that allowed him to bend and extend hours and to remain unencumbered by a prescribed curriculum. This casualness even made it possible for some cash-strapped students to avoid paying the Polytechnic’s small fee. Most importantly, he was free from educational conventions. He prefigured the social emphasis of learning in educational theory by breaking away from the practice of introductory teacher demonstrations, honing a feedback-based teaching style at variance with the then common ‘banking concept’, critically defined by radical educationalist Paulo Freire in 1972.27 Bomberg’s classes revolved around close individual feedback and the encouragement to ‘keep the paint moving’, or in other words, to learn through doing.28 In some respects, the classes were conventional life rooms: students worked in paint or charcoal using desks and easels arranged around a live model (fig.2). But in contrast to traditional practice, students were encouraged to stay in one place and make numerous drawings, paying attention to the different ways to express how the body fit compositionally into the space around it, as well as how this spectacle affected the body and mind of the artist. This subtle, yet dramatic instruction runs counter to the more common practice of making drawings from different points around a model, where a three-dimensional understanding is built in the student’s memory of the body as an anatomical puzzle – the method Bomberg himself was taught at the Slade.29 Anatomy, naturalism and getting it right were less important than attending to how the act of making reverberates between artist and subject. Bomberg’s only props were selecting the right pose and noting how light changes formal relationships. No coloured or elaborate light set ups were used; instead Bomberg encouraged his students to mark the differences between a soft morning glow, midday brightness, the flattening distortion of passing clouds or the force of electric lamps.30 The result was a prescient learning environment that not only honed specific activities, but also intimately involved the class as a social community that facilitated lateral learning. Full participation entailed constructing an identity as artists in relation to one another.31

The Borough class as a whole can be understood as a cluster of overlapping sub-communities. Participation varied over the eight years that the class ran with students coming and going, often moonlighting from other art colleges across London. The core of aspirant artists included Frank Auerbach, Dennis Creffield, Cliff Holden, Leon Kossoff, Edna Mann, Leslie Marr, Dorothy Mead, Dinora Mendelson, Gustav Metzger, Roy Oxlade and Miles Peter Richmond. To a large extent, particularly during the early phase, this community was also self-selecting. In his memoirs, Holden reminisced that he and Mead recruited students from pubs in Soho as well as from other art schools.32 Holden brought in Creffield, and Creffield in turn introduced Oxlade.33 Auerbach initiated Kossoff, and Mendelson recruited Richmond, Marr, Len Missen, Peter Lasco and Alan Stokes.34 Creffield spoke of life modelling for other classes, where he proselytised to likely candidates as he examined their work during the breaks.35 The core of the class was thus a loose nucleus of participants sourced from a larger network of art students in London. The class also contained those who attended without intention of becoming professional painters, including Polytechnic students dipping in as well as other drop-ins, who were either augmenting different art sector degrees or simply honing an amateur practice.36 This group formed the substance of the class and deserves consideration, as their presence helped to define how the aspiring and professional painters in the community defined their own distinct purpose in contrast to the wider community. And a sense of Bomberg-centric purpose for some students became fanatical.37

The intimacy of Bomberg’s classroom community, his impassioned personal philosophy and the respect he extended to its participants by calling them artists punctured any illusions of pedagogic distance or impersonality.38 He taught a worldview and a way of life, not simply a style of artistic practice. The most dedicated of his students took this to heart. From the domain of the classroom, two movements-cum-exhibiting collectives quickly formed, but there were also student cliques – such as Auerbach, Kossoff and Philip Holmes’s ‘Gang of Three’ – and a surprising number of romantic partnerships and marriages: Mead and Holden, Dorothy Missen (née Bergan) and Len Missen, Mann and Don Bradman, and Mendelson and Marr.39 The two main groups were the Borough Group (1946–1950) and the Borough Bottega (1953–c.1955). The Borough group was a student-founded exhibiting collective, which in its early years had affinities with the Quaker principle that a community had the potential to fortify each member’s individual integrity.40 The Borough Bottega was founded later by Bomberg as a consciously hierarchical organisation that emulated his understanding of a Renaissance-style workshop. I will return to how these operated as communities of practice in relation to Bomberg’s teaching philosophy, but since the Borough Group and the Borough Bottega are frequently conflated or substituted for one another, it is important to note the distinctions between the types of networks that radiated out from Bomberg.41 It is, in addition, important to keep the consciously formed groups distinct from a wider and later tendency towards the use of thick paint and pugnacity, which spread rapidly through second- and third-degree contact with Bomberg and his teaching methods. It was this tendency that inspired Sylvester to describe it as a ‘serious new trend in painting’.42

Many names for these diffuse networks soon followed. More often than not they were not well received. Helen Lessore, the influential director of the Beaux Arts Gallery, dismissed the trend as creating many ‘little Bombergs’.43 More sympathetically, Sylvester called them ‘Bombergers’, and other names included ‘Bombergians’, ‘Bombergists’, ‘the Bomberg Movement’ and ‘the School of Thick Paint’.44 The uniting characteristics were loose tendencies towards expressionism and impasto that knitted together the figurative and the abstract. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, however, these were interpreted in a range of disunited ways that should not be mistaken for a movement or community and not confused with either the Borough Group or Borough Bottega, both of which were consciously formed. The influence of this trend in aesthetic thinking should not be underemphasised. It combined with the allure of American abstract expressionism to fuel a fusion of the figure with abstract tendencies, utilising lush colours and thick painting. These features defined the innovations of the ‘long Sixties’ and raised British painters such as Frank Auerbach and Francis Bacon to global prominence, and later the neo-expressionists such as Paula Rego and Christopher Le Brun.45

Bomberg’s teaching philosophy

Fig.3

David Bomberg and Richard Michelmore

Recto: Messiah. Verso: Messiah 1953

Tate

© Tate & Richard Michelmore

Bomberg’s teaching revolved around appealing to an innate creative sensitivity within each student. He famously contended that ‘art cannot be taught but draughtsmanship can be taught to those who have a natural gift’.46 Teaching by encouraging personal vision through personalised feedback presents significant challenges in maintaining rigorous expectations. Bomberg navigated this by inspiring students to pay close attention to the quality and intensity of their visual engagement. His feedback not only challenged a student’s looking by encouraging critical awareness of visual assumptions but also critiqued the student’s mood and emotional relationship with the subject. Evocation became an important tool, as Bomberg sometimes gave feedback in the form of rhapsody, sometimes in unlikely associations and sometimes in poetry. Oxlade described one such instance of feedback in the life room: ‘He looked at my drawing and then at the model, and after doing this several times more, he drew in pencil, very lightly two dome shapes one above the other and said ”the dome of St Paul’s is like this and not like this”’ – a remarkable comment given that Bomberg intended the dome of St Paul’s cathedral to challenge Oxlade’s treatment of a human body.47 Creffield noted that Bomberg pushed him to pay more attention to light effects by quoting a line of poetry or referencing a phrase of music.48 Holden further recorded that ‘if the student were facile, using an aesthetic line, then Bomberg would give him a great lump of charcoal and cite Modigliani and [Augustus] John as examples of men who would tie the tool to the big toe to escape the domination of a facile hand’.49 Inspiration and stimulation could help maintain the sensitivity and intensity of engagement that was necessary during painting. Such individualism could have led to lax permissiveness, but in Oxlade’s words: ‘Bomberg did not tolerate unstructured personal vision – generalities would not do. Bomberg believed one must be specific, but specific according to one’s own idea.’50 And, crucially, this method of teaching reduced the risk of students emulating his own manner of making art. This charge was later levelled at him and he did sometimes follow an older convention of demonstrating his critique by painting or drawing onto a student’s piece. In the case of Messiah 1953 (fig.3), the student-turned-architect Richard Michelmore asked Bomberg to co-sign the piece after such feedback turned into something more like collaboration.51

Bomberg’s preference for evocation instead of demonstration, however, does not mean that his feedback was entirely reactive to his students. There were core principles imparted that came to be known as his ‘approach’ by his students. At its heart, this approach involved both a sense of integrity about how one interacts with the creation process and being informed by a strong historical sense of purpose. The best known shorthand for his approach was that painters should search for the ‘spirit in the mass’, the most contentious of Bomberg’s key phrases.52 Students and scholars have understood this phrase in different ways. Oxlade called it ‘the return of art making to a basic language where art and nature achieve synthesis; where shared physical experience and invented form are held in creative tension’.53 Holden characterised it as the melting of the artist into the creative act, where the artist becomes one with the spirit through participating with the mass.54 Creffield likened it to a sense of creative integrity.55 Bomberg positions it in his notes as a means of resuscitating artistic sensitivity: ‘Our approach to mass preserves our humanity – it is more of the spirit and less of the machine.’56 Read together, these references contain three operations: a compositional coherence, where marks are read as autonomous traces of gesture as well as a united mass that is emotionally affecting; an observational component, where the indefinable vitality in the definable objects, which comprise a given scene, is identified; and finally a process where the body of the artist taps into this vitality. Yet the concept is not rigorously definable and perhaps was never intended to be. Bomberg was eloquent – despite his disavowal of over-intellectualising art education – yet he rarely demonstrated an interest in straight communication.57 There is something deliberate about the slipperiness of ‘spirit in the mass’. The catalogue for the Borough Group exhibition of 1949 boasted of the repeated refusal to clarify the concept – given that many of the exhibition’s student-participants did not maintain this stance in later years, it is possible that the refusal was primarily Bomberg’s.58

Beneath the differing interpretations, Oxlade argued that the ‘spirit in the mass’ is ultimately a ‘general poetic concept’ rather than a specific value or set of values.59 I agree, but would go further: its action was fundamentally, like the evocation Bomberg used in his feedback, not meant to direct the students towards something concrete, but to destabilise them, break entrenched habits, open up their ways of interacting with their own processes and keep them questioning different possible meanings. In this sense it operates more as a mnemonic signpost for a manual pathway, just as names for piano scales do not convey how to play the scales themselves, but allow us to tag the discovery we make on our own so we can return to it at will. In this sense the ‘spirit in the mass’ is not so much a technique or style as it is a highly personal habit that can be trained – a sense of corporeal and creative integrity based on surrendering completely to the sensory spectacle of the creative process. Precisely because of its ambiguity, invoking the ‘spirit in the mass’ became a means of performing one’s participation in or sympathy with Bomberg’s student community. As his popularity grew among those who had not attended his classes, the importance of wielding this term grew.

All of the various meanings of ‘spirit in the mass’ are part of a greater re-thinking of what it means to be an art-maker – the inculcation of some sense of artistic integrity that focuses not on the artistic products as much as on the quality of engagement with artistic practice. This was apposite, given the rise of the conceptual turn from the mid-1950s on.60 This connection with integrity is evident in many students’ reminiscences, particularly those of Creffield and Oxlade, but it was connected to Bomberg’s consciousness of art history. He claimed a privileged understanding of an older, more red-blooded and socially necessary artistic tradition. The figures within his tradition were the same artists’ artists and movements whose names were hailed in more conservative classrooms – Giotto (died 1337), Michelangelo (1475–1564), Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Raphael (1483–1520), Rembrandt (1606–1669), Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779), Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and Vincent Van Gogh (1853–1890). Bomberg added cave art to the beginning and cubism to the end, but otherwise the largest difference from the traditional cannon was his interpretation. These artists were great, suggested Bomberg, not for their stylistic genius, but for the force of their personalities, which allowed them to maintain the courage and authenticity of engagement necessary to throw body and mind wholly into the existential conundrum that is art making.61 Theirs was a direct, electrified and humbling connection with the world.

Bomberg argued, in his notes and to his students, that systemised art education had precipitated a hiatus in the tradition, since the art school’s inception in the seventeenth century. This method of learning, he contended, had tamed the urgent productivity of the cave painter into a sporting pastime, a genteel engagement that was subject to polite conventions. Art had become over-intellectualised, ‘too conscious and stale’; artists had too many theories of approach and styles that were too academically overdetermined.62 The artist William Coldstream and the ‘measurers’ he inspired (an imposed label, much like the ‘Bombergians’) were the main target of this criticism, but artists he considered over-intellectualised also included Henry Moore, Mathew Smith and Graham Sutherland.63 According to Bomberg’s thinking, the solution was not only to learn through hands-on exploration but also through attending to how art history has been misunderstood – the true measure of Michelangelo’s greatness was his personal integrity as an unbending individual, for this was the trait that propelled him into the main tradition. It was an extension of Bomberg’s younger self-styling as a rebel outsider, but the difference was that now he saw this truth-to-self-rebellion as a forgotten norm. Through being stubbornly individualistic, one could gain access to a more substantial and rewarding imagined historical community. This was inspiring for aspiring artists looking to his authority as a teacher as much as it was fortifying for Bomberg, reminding himself of the importance of maintaining his own practice. It suggests, I contend, that his practice was much more intimately linked to his teaching than has been previously acknowledged.

Aligning the teacher and the artist

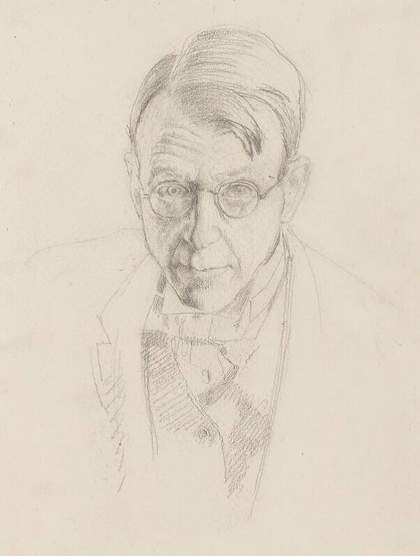

Fig.4

David Bomberg

Head of a Poet [Isaac Rosenberg] 1913

Location unknown

© The estate of David Bomberg

Force of personality was a leitmotif of Bomberg’s life and lifelong work. It was in part his flair for asserting nonconformity that propelled him to achieve acclaim early in life. From a poor background as a first-generation Polish immigrant living in a Jewish community in East London, Bomberg bucked at more practical applications for his evident talents, achieving a place at the prestigious Slade School of Art in 1911. Here, he joined a student body that was particularly energetic and well placed to respond to the ‘art-quake’ triggered by the Post-Impressionist exhibitions of 1910 and 1912.64 Bomberg was a gifted and successful student – winning the 1913 Slade drawing prize for Head of a Poet [Isaac Rosenberg] (fig.4) – but he adapted poorly to the mannerly educational environment of the school and wrote scathingly of what it represented throughout the rest of his life. After several incidents, which included breaking a palette over the head of his esteemed tutor Wilson Steer, he was expelled in June 1913 for being ‘a disturbing influence’.65

Fig.5

David Bomberg

The Mud Bath 1914

Tate

© Tate

And yet by the spring of 1914 he was thriving within an expanded art scene: he was exhibiting with the London Group, which he co-founded; he selected for and exhibited within the Whitechapel Gallery’s Twentieth Century Art: A Review of Modern Movements; and he exhibited as an invited non-member with the vorticists at the Dore Gallery in June 1915.66 The pinnacle of Bomberg’s early career was a solo exhibition at the Chenil Gallery, Chelsea in July 1914, where he exhibited fifty-five pieces including the bold The Mud Bath 1914 (fig.5), which he hung on the exterior of the building. The vitality of this masterpiece of multi-figure composition, among other similarly spirited paintings such as Ju-Jitsu c.1913, caught the eye of collectors, critics and fellow artists.67 During this youthful flourish – Bomberg was only twenty-three years old in 1914 – he defined an urban variant of the avant-garde, bohemian outsider. And yet by his middle age he came to represent a very different ‘outsider’: the lone master of his craft, standing steadfast against critical neglect.68

The tragedy of the First World War is widely blamed for spurring Bomberg into a retreat from mechanised and hard-edged imagery, propelling him into decades of experimental naturalism.69 The war was a harrowing event for Bomberg, followed by a steady withering of his critical acclaim and financial supports. The trauma of Bomberg’s war should not be underestimated: he enlisted in 1915 with the Royal Engineers, transferring a year later to the King’s Royal Rifle Corps; he saw action and horrors on the Western Front, and in 1917 he attempted to end his war by putting his gun to his foot, only to be sent back to the front as a runner. His self-inflicted injury was an act of desperate protest (he refused to pretend it was an accident) and it was the most extreme expression of a desperation, which would feed into the depression that accompanied him for the rest of his life.70 Too much, however, can be made of the First World War as an aesthetic break. The lush yet melancholy painterliness which he crept slowly towards after Armistice certainly does not build from his early futurist-inspired revelry in mechanical violence and urban vitality. There is something, however, lurking in these early pieces that broadens and is better articulated in his later pieces. Throughout all three broad phases, which constitute his practice – early cubo-futurism (c.1911–c.1919), interwar experimentation (1920–c.1929), and his mature, thick-paint period (c.1929–1957) – there is a distinct ideological and aesthetic continuity across his career for an organic, human engagement.

In reconciling teaching and art practice it is also important to reconcile Bomberg’s aesthetic phases. Though it is tempting to treat his early and late manners as distinct engagements, it is more constructive to compare what they hold in common. I propose that they were both governed by a set of core interests in the impossibility of human free will, which found full expression when the materials, means and subjects all contributed to this emotional drive. In The Mud Bath, Bomberg’s virtuoso organisation of the segments within the composition makes them subordinate to the greater whole; and yet simultaneously they pull away into phrases of formal relationships. This is achieved in The Mud Bath in an abstract language. Bomberg’s disinclination to abandon reference to the human body emerges in the title, which urges the viewer to remember that this is a bathing scene, not merely a dynamic surge of forms; yet it is the flow and isolation of these forms that animates the composition. The clusters of figures, such as the two-part limbs at in the central foreground, play an important role in leading out eyes around the swirl of the greater composition but they also operate as a self-contained segment. The white and blue, the shape, the way they bisect the central column, all energise our uncertainty in identifying them anatomically and resolving perspectival distance. They are unto themselves intact within the greater composition as well as subordinated to it.

While the spectator position was left underdeveloped in earlier canvases such as Ju-Jitsu, The Mud Bath draws the spectator in. We know our position in relation to the emerging and dissolving beings below from a distance that closes the longer we regard the piece – the red shape of mud tilts up and seems to swell as the human-shapes swirl into it; the vertical beam of brown, rather than grounding us, instead takes on a menacing solidity. This is a nightmarish world where the gleaming white and blue of figures, coloured as if mutated classical sculptures, dissolve and emerge from a bath of blood-like mud. Two pieces that share affinities with Bomberg’s bathing subject and his abstract language, respectively, are Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s classically sentimental A Favourite Custom 1909 and the indictment of an urban community as an inhuman mob by vorticist leader Wyndham Lewis in paintings such as The Crowd c.1915. Unlike these, however, Bomberg visually withholds from using either figuration or abstraction as means of pronouncing morally on either dehumanisation or transcendence.

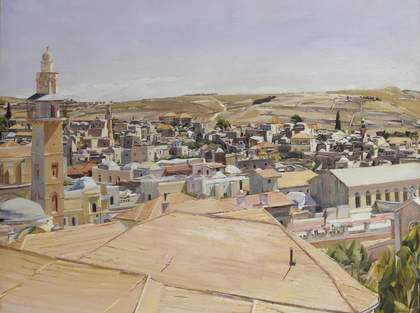

Fig.6

David Bomberg

Jerusalem, Looking to Mount Scopus 1925

Tate

© Tate

There is a flat affect to Bomberg’s un-forming and forming of what could be intact humans. Again and again in his early pieces, abstraction becomes the means of articulating a pulsating picture ground that stands in for a matrix, be it architectural, societal or historical, that the lone human cannot escape. During Bomberg’s transitional period, particularly the pieces he made during his residency in Jerusalem, such as Steps to a High Place, Petra Early Morning 1924 (private collection)) and Jerusalem, Looking to Mount Scopus 1925 (fig.6), the rooftops and angles of the buildings grow pregnant with thicker paint. It is as if their structures, being naturalistic, allowed Bomberg to relax his former imposition of abstraction and instead explore how his painting-manner and materials could in themselves better express certain qualities of the human experience that he had long courted. These qualities included how the spaces human bodies create and are created from are organic and fragile while at the same time confining, shaping and decisive.

Fig.7

David Bomberg

Self-Portrait 1956

Borough Road Gallery, London

© The estate of David Bomberg

This union of materials, means and effects to composition and emotional content reaches fullest expression in mature pieces such as Self-Portrait 1956 (fig.7) and Mount St. Hilarion, Cyprus 1948 (Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums, Aberdeen). In Self-Portrait the sense of structure and mass, paint and practice achieve a tense equilibrium. It is one of a final set of haunting portraits and self-portraits, mostly produced in a remote and derelict villa on the outskirts of Ronda, Spain.71 In all these works, the paint is heavy and earthen-coloured; the strokes are predominantly long, thick and vertical and yet they spill around the central figures. In Self-Portrait these strokes create a disordered tumble above Bomberg’s head and lap loosely into a blue-black collar of his smock. The effect is that the ground of the painting surges forward in a sinuous shimmer of pinks and browns. The central figure, rather than sitting on top of or in front of this pulsing background, instead appears swallowed, as if drowning or sinking, fighting against a slow dissolve into un-recognisability, much like the figures in The Mud Bath. Here, however, the paint itself – its effects, textures, beauty, and very moist plasticity – becomes a proxy for the threatening presence that mud held in the earlier painting. Self-Portrait’s facial features are mere blots: a few strokes of umber here and there, leaving the eyes hollow and unarticulated as if the sockets of a skull. The top of the head, exposed by balding, glistens with an economy of thickly worked brushstrokes in light tones that are worthy of satin drapery in paintings by the artist John Singer Sargent.72 The mass of the central figure is a unified mass; at the same time it is impossible to ignore the complexity within the great sweep of pyramidal human form that takes up most of the picture plane and is so deftly rippled with strokes of different thicknesses and angles. In Self-Portrait, Bomberg thus achieved a sense of great weight – he replicated the monumentality of The Mud Bath in a piece only a fraction of its size and with a portrait-subject both mundane and intimate. It is a faceless face, horribly crushed, and tenderly tilting, evocative of the pathos of futile assertions of importance. The energy and import of the paint and painterliness allow us, the spectators, to feel the pathos and complexity of the painting’s true subject: mortality and the simultaneous futility and all-importance of maintaining a sense of self in the face of the inevitable passage of time.

Fig.8

David Bomberg

Ronda 1935

Private collection

© The estate of David Bomberg

Fig.9

David Bomberg

Tajo and Rocks, Ronda 1956

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

© The estate of David Bomberg

Teaching for Bomberg contributed to his evolution as a painter. It facilitated his artistic development, if not aesthetically then certainly by helping him channel the psychological strength needed to stand steadfast in his aesthetic ambitions against critical neglect. It is difficult to map the major landmarks of Bomberg’s aesthetic development onto his teaching practice – his mature period began with his Jerusalem paintings in the 1920s, predating his teaching practice. And yet clinging to such landmarks is reductive. The encouragement emanating from a supportive student community at the Borough has a subtle manifestation in his work. The awkwardness, tentativeness or despair that clings to some of his pre-Borough works, such as the potent anguish of his flower paintings or his uncomfortable attempts at becoming a portrait painter, ebbs away once he begins teaching at Borough.73 A sense of tutelage to the natural structures that lingers in pieces such as Ronda 1935 (fig.8) is fully liberated by the time he painted Tajo and Rocks, Ronda 1956 (fig.9), where without apology his modulation of hues and textures delineates a great wall of earth, kindling mesmerising variation against the shallow pictorial depth. Bomberg found it hard to paint during his teaching periods, but this seems to have merely compressed his energy and creativity into painting trips – such as those to North Devon in 1946, Cornwall in 1947 and Cyprus in 1948.74

Fig.10

David Bomberg

Ronda-el-Castillo 1956

Borough Road Gallery, London

© The estate of David Bomberg

Fig.11

Henry Tonks

Self-Portrait c.1900–25

National Portrait Gallery, London

One aesthetic change that may be linked to watching his students is Bomberg’s use of erasure in charcoal. Rubbing an eraser over built up tonal layers and thus creating smears and voids became a crucial device for many of Bomberg’s students. It was largely absent, however, from Bomberg’s technical toolbox until around 1954–6, with the exception of preparatory studies of the 1910s, such as Racehorses 1912–3 (Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, London) and Wrestlers 1912–3 (private collection). Some works, such as Ronda-el-Castillo 1956 (fig.10), appear to have erasure, but on close inspection in the flesh, do not. Instead they depend upon a more fragile attentiveness to layering tone, protecting sections of void, which creates shimmering layers, untrammelled by the eraser’s smear and compression of the paper’s surface texture. For some artists of the inter-war period this was a technique tantamount to moral behaviour. This is particularly true of those who had studied in the drawing rooms under Henry Tonks, who continued a Slade tradition of linear drawing which, as the critic DS MacColl vividly stated, sought ‘definiteness of stroke as opposed to lazy fudging’.75 A ‘bad drawing’ for Tonks was reputedly ‘like living a lie’;76 good drawing was the delicate and patient layering of sharp lines that paid attention to form at the expense of light and tonal mass, which, if unavoidable, could be indicated by a minimum of hatched linear shading.77 These commitments are evident in his self-portraits of c.1900–1925 (fig.11).

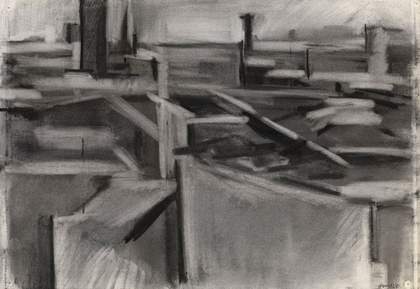

Fig.12

Dorothy Mead

Rooftops in London 1967

Waterhouse & Dodd, London

© The estate of Dorothy Mead

Fig.13

David Bomberg

Sunlight in the Valley, Ronda 1956

Private collection

© The estate of David Bomberg

In complement to such delicately accreted drawings, in the 1930s the poet, artist and writer Adrian Stokes popularised an aesthetic theory of ‘carving’. The theory was developed by key members of the Euston Road School into an emulation of sculpting away marble by laying successive stratums of paint- or pencil-shading that worked over the entire surface of a picture – darkening and never lightening – in order to unlock an almost mystical inner vitality.78 Erasure violates such virtues; to the historically conditioned eye of the early twentieth century in Britain, it suggested a professional, moral and technical lack. The great majority of Bomberg’s charcoal pieces retain vestigial traces of this notion of ‘honourable’ technique.79 His students in contrast largely opted in favour of energetic freedom, which resulted in some of this network’s finest pieces, such as Dorothy Mead’s Rooftops in London 1967 (fig.12). It is possible that the exquisite, erasure-aided surface modulations of Bomberg’s Ronda with Iglesia Espiritu Santo, Andalucia, Spain 1954 (private collection) and Sunlight in the Valley, Ronda 1956 (private collection) (fig.13) were encouraged by his students putting Bomberg’s own theories into practice in ways he had not yet dared. It is a link that is hard to conclusively prove, but one that suggests additional ways in which teaching strengthened in Bomberg what trauma, depression, and critical neglect had dampened.

Integrity and community

At the heart of the energy and cross-fertilisation between Bomberg and his classroom discussed so far is a greater sense of the Borough classroom as a community of practice, with Bomberg’s emphasis on a sense of integrity at its core. In the 1980s Creffield reflected that Bomberg ‘never taught a style of drawing but tried to help the students to aim in the right direction – to develop – a moral disposition – the artist as a man’.80 In a note found after Bomberg’s death, Bomberg reflects on the nature of this ‘moral disposition’:

There is inherent in the structure of moral values an integrity, which performs but does not think. It will help sustain strength – the seat of which may be located in the mind; it cannot be seen but we know it is there, because it is operative. The desire for truth radiates from it. It becomes Fine Art when it is integrated in form. Not to possess it is to know you are no artist and for an artist to possess it and to sacrifice by compromise for expediency is to degrade it and the artist.81

The litmus test here is crucial: artistic worth is judged by a psychological quality that is invisible except through practice; and if it is present, it must be honoured properly in order to remain effective. Bomberg’s words are those of someone propping up their personal need to identify as an artist and goading himself against the temptations of concession or convenience. Resisting monetary temptations is all the more painful when an artist, like Bomberg, has a growing family with insecure and insufficient finances. Bomberg’s sense of integrity is a mantra and a strict personal code. The community around him evolved into a vehicle for justifying and policing such sacrifice and artistic morality. That a group could be a vehicle for sustaining individual integrity might seem contradictory, yet it was precisely this potential paradox that fuelled the Borough Group. Indeed, it is probable that the Group’s ambition to fortify each member’s individual principles through community support was inspired from Quaker beliefs.82 And it is this function of the Bomberg community that makes it exemplary of Lave and Wenger’s conception of communities of practice: ‘learning involves the whole person; it implies not only a relation to specific activities, but a relation to social communities – it implies becoming a full participant, a member, a kind of person.’83 The kind of person in this case was an artist who identified as an outsider, demonstrated through the personal intensity of their emotional-imaginative response to nature, and who did not bow to social or economic pressures. The group identity involved inspiring and policing devotion to the necessary artistic integrity. In keeping compassionate competitiveness visible, such a group could effectively counteract quavering resolve.

Bomberg’s actions demonstrate that an integrity-enforcing community was just as valuable to him as it was to his students: he expended great personal energy tying to ensure that, for rest of his life, some form of the Borough community continued. The teaching approach that Bomberg developed (that of a mentor/master) did not end when he left the Polytechnic in 1953. Soon afterwards he founded the Borough Bottega and when it too petered out in 1954, he attempted to revive and refine it further as an international school, this time at the Villa Paz in Andalucía.84 Paz would have been the fulfilment of the workshop-model of a community of practice, involving a communal studio space.85 The Borough student Miles Peter Richmond joined Bomberg in Andalucía to help establish the community, and on Bomberg’s behalf he invited a wide range of erstwhile students from both the Group and the Bottega to live and work for short, intense periods. When the school received only one fee-paying pupil, however, it shuttered before it opened, though Richmond and Bomberg remained in Spain until Bomberg fell ill and returned to London, where he died in August 1957.86 These escalating versions of a Renaissance-style workshop were, for Bomberg, a liberation of the classroom community, removing it from the sterilised roles that he saw as having emerged with the professionalism of academy schools during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.87 The different ages and experiences of artists working alongside each other (or as he called it ‘working as a team’), in contrast, derived its strength from the full-being exposure, lateral influence and communal intensity.88 That Bomberg wanted this form of working within a context where he was the ‘master’ is also significant. It reveals another benefit of the community for Bomberg as an artist, that of fuelling his particular and self-fortifying historical mindedness.

Bomberg’s restyling of a Renaissance workshop separates his identity-performance from that of other members. By positioning himself as a master he was able to create a space for himself within his interpretation of art history, or his main current of tradition. Bomberg had long defined himself as an artist-rebel, just as Augustus John (1878–1951) had done before him and Damien Hirst (born 1965) would do after him. In his youth Bomberg upheld the image of the artist as endeavouring to be ‘authentic’ in an inauthentic world, demonstrating his individualism through refusing the mainstream.89 In his later career this became less of a performance and more of reality as he was increasingly cut off from art world discourse and isolated in his own preoccupations. While he found energy and solace in the community of his students, he could not stop from identifying authenticity with being an outsider. The Renaissance workshop as a model resolved this. It allowed him to relax into a community while remaining an outsider. It also enabled him to imaginatively participate in a genealogy of great artists through history.

For Bomberg, teaching and history were intimately linked: among the papers found upon his death were notes for a syllabus in 1937, which outlines his notion of a main current of tradition with a thoroughness disproportionate to the practical instruction he was periodically imparting to evening class attendees at the time; I agree with Cork that it was unlikely to have ever been delivered.90 The syllabus therefore demonstrates that teaching as a conceptual activity was important for Bomberg, and one function of this conceptual activity was the participation in a historical tradition previously discussed. He imagined this tradition as a kind of ‘monumental’ history to which he turned as if it were a balm against the unsympathetic and thus isolating art world of his peers. ‘Monumental’ history, according to the thinking of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), is understood as the history of great people, who together create a chain running through known history; Nietzsche likens this chain to a mountain range.91 Nietzsche’s warning about this interpretation is further applicable to Bomberg, for this form of history allows one to transfer authority from one’s peers to an imagined genealogy, which one hopes to eventually join, as Nietzsche articulated in ‘The Use and Abuse of History’ in 1874:

Whoever has learned to recognise this meaning in history … his goal is happiness, not perhaps his own, but often the nation’s, or humanity’s at large: he avoids quietism, and uses history as a weapon against it. For the most part he has no hope of reward except fame, which means the expectation of a niche in the temple of history, where he in his turn may be the consoler and counsellor of posterity.92

Teaching here becomes a means of speeding the mechanism of time and assuming the roles of both consoler and counsellor during one’s own lifetime. Yet the eventual tensions of how Bomberg related to his students are inbuilt: he engaged in an actual community only to reassure himself a place in an imagined historical community, one he can only join by assuring that he was at the mountain’s peak. This mirrors his uneasy relationship to the Borough Group with its egalitarian intent, in contrast to his position as master to the followers of the Borough Bottega. The overtness of Bomberg’s need to have followers in order to see himself as a master unsettled some students, such as Leslie Marr, who remembers an incident where a group of drawings by several students became confused: ‘I noticed Bomberg, with a big smile on his face. He came over to me. “Just like the old apprentice system,” he said, “when the apprentices’ drawings all look the same.” This gave me a jolt, but I thought, well, this is the price one pays for this intensity of teaching.’93 Bomberg’s intensity was linked to his historical-mindedness, as is evident in another reflection by Marr: ‘ [Bomberg] led us to believe that we were going to change the course of British art for ever.’94 That Bomberg inspired young artists with the belief that they could rectify the hiatus in the current of tradition, righting the aberration of recent history through the force of their personalities, is evident. It is also clear that the students, or followers, as he styled them, enabled him to perform his own identity as a master. For him, the gains of the community were thus not only the invigoration of keeping company with young, sympathetic and energetic artists, but also the self-performance of his own centrality within history. This, however problematic, allowed Bomberg to reap the benefits of his extended classroom community without sacrificing his own sense of individuality.

Coda: reconsidering the artist-teacher

Teaching and making were entangled for Bomberg. Both activities emerged from similar preoccupations: grappling with the place of the lone human within the architectural, societal and historical structures around him. Teaching had two main benefits for Bomberg: first, the content and delivery of his teaching helped clarify and enforce his sense of self; second, the community strengthened him and gave him not only a network of fellow artists but also helped him conceive himself within a community of monumental history. It also inoculated him from an unsympathetic network of his erstwhile peers, a late-life neglect that is painfully evident in two notes in the journals of William Townsend, a tutor at the Slade. The entries occur after Bomberg’s posthumous Arts Council exhibition in 1958, organised by Andrew Forge, the then-lover of one of Bomberg’s former students. Townsend writes: ‘The Bomberg show at the Arts Council is splendid and the least the Arts C[ouncil] could do for his widow. I don’t know how many times I urged Bill [Coldstream] to get them at least to buy a picture or two from him while he was alive.’95 A month later, he noted: ‘David Sylvester proposed that he [Bomberg] was the best English painter since Sickert.’96

For an artist so great and so neglected to have remained so steadfast is remarkable. Contrary to what one might expect, as he grew older and more deserted by institutions such as the Slade and the Arts Council, Bomberg’s pieces became more fearless, sensitive and probing. Bomberg’s personal willpower has been credited for this endurance and blossoming, but also deserving of credit is his teaching experience, which offered both empowerment and stimulation. He seized an opportunity to craft an unconventional classroom, and he attracted students who were primed and eager to extend his principles through social as well as aesthetic practice. Art making and teaching were part of a single practice and identity for Bomberg. It is reductive to consider them rival activities that competed for finite investment. Bomberg respected art making as an alternative form of thinking, something extra-rational and extra-lingual, which emerged from a grey area of mingled physical and mental intuition, feeling and understanding. Teaching entered and strengthened him during a similar grey area of his life. To ignore the possibility that his teaching may have benefitted his art is to import an outdated stigma against teaching art, as it is to misunderstand Bomberg’s own experience of the classroom as a community, which gave him the courage to pursue his artistic practice with a renewed vigour and boldness in defiance of critical and market neglect. He changed and was changed by the experience and the history of art is the richer for him doing so.