Fig.1

John Constable

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows exhibited 1831 with its previous, rococo-style frame

Tate

Fig.2

Installation view of J.M.W. Turner’s Caligula’s Palace and Bridge (left) and John Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (right), both exhibited 1831, in their new frames in the Clore Gallery at Tate Britain

Photo © Eddie Mulholland

When acquired by Tate in 2013, John Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows exhibited 1831 was in a rococo-style frame (fig.1), initially believed to be a twentieth century reproduction. It was in this frame that the painting toured the UK until 2018.1 When it returned to Tate Britain, it was displayed in the Clore Gallery in a new frame alongside J.M.W. Turner’s Caligula’s Palace and Bridge, also reframed, which had first been exhibited beside Constable’s painting in the 1831 Academy (fig.2). This was a partial reconstruction of the original hang and re-framing both pictures in a more historically appropriate style was designed to enhance the display.

The rococo-style frame was shallow and narrow, with repeated deep-sweeping curves set between cartouches at the centre and corner of each side. At accession it was decided by Tate curators and frame conservators that this frame was wrong both historically and aesthetically, its decorative form and dull brown-gold appearance deadening the painting’s impact. Cleaning the frame to lift its appearance was not thought adequate and it appeared to have minimal contextual value, being most likely a later replacement of an unrecorded original. However, while the rococo frame was regarded as inappropriate to the work, an array of exhibition labels on its reverse revealed its connection with the painting to be somewhat longer than first thought.2 The frame and labels tell us about the story of the painting as an object and the value a previous owner placed on Constable’s work. Consequently, since reframing would make a significant break or intervention in the historical record, it needed to add substantially to the appreciation of the artwork while being a historically and aesthetically believable object itself.

This paper considers several topics: the way frames can affect the viewer’s perception of a painting; pressed composition ornament and frame making; Turner, Constable and frame makers around 1830; the rococo frame itself; the validity of reframing and alternative approaches; the frames of other paintings by Constable; and the process of sourcing an appropriate model and realising a replica.

Experiencing frames

When a viewer looks at a painting, they experience the interaction between an artwork, frame and surrounding space, but usually without giving much thought to this interrelationship. The frame inevitably affects their perception of the painting, but should ideally elicit no response – the task of the frame is ‘to draw attention away from itself’, while the artwork should hold the viewer’s attention.3 Nonetheless the frame’s profile, ornamentation and condition cannot be ignored altogether and any framing ‘intervention’ is bound to alter the way the image is seen.4 Continuing developments and improvements in the preventive care of paintings – such as the addition of backboards and glazing – have resulted in museum frames undergoing successive alterations which have generally prioritised function over appearance.5 A frame may also be judged intrusive: bright gilding may distract from the artwork or conversely a degraded frame with ornamental losses is off-putting – ‘a brown painting in a brown frame’ has been a perception held by some of the contents of galleries showing work from the nineteenth century and earlier. The frame is there to draw the viewer forward and best present the work without having too distinct a presence itself; it also provides a perceptual break between paintings. If the thought arises that the work might have been better served without its frame, then that frame might be considered to have failed in its role.

Philosopher Barbara Savedoff has argued that in most cases it does not hold that a particular frame ‘is irreplaceable and ontologically bound to its painting’, even where it can be shown that an artist designed it or the first patron commissioned it.6 In the non-museological sense this may be so, in that we see paintings illustrated without frames and seldom think something is missing.7 Only in relatively few examples (notably Pre-Raphaelite frames) does a frame reference the story or the visual details of a painting and even in these cases the enjoyment of the artwork as a painting is not reduced, although the historical understanding of the artwork as an object of its time may be. A frame nonetheless disguises the ‘objecthood of the painting … Without a frame we have a three-dimensional object with a picture on its surface; with a frame, we have a window through which we glimpse the space’.8 A frame if not a particular frame is generally recognised as necessary for the fullest appreciation of a painting depicting a fictive space such as that in Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows.9

In a gallery such as Tate Britain where the display is broadly chronological, the viewer traces, without necessarily being aware of doing so, a line in the history of decorative arts through frames. At a conscious or subliminal level, this offers a measure of historical context to each artwork, adding at the same time a visual richness to the experience of viewing paintings in a nineteenth century building.

Composition ornament and frame making in Britain

Around 1800 there was a change in picture frame ornamentation – from woodcarving to embellishment with pressed composition. The new technique, in which lengths of ornamentation were turned out from reverse-carved boxwood moulds, was quick to produce and cheaper than equivalent lengths of carving. The basic recipe used today involves adding rosin dissolved in raw linseed oil to melted animal glue and bulking up the mix with chalk to create a material with the consistency of dough. Moulded materials for adorning frames had existed since the sixteenth century, while other composition-like materials were patented during the later eighteenth century and used primarily in interior decoration.10 It remains unclear, however, who exactly originated, popularised or first successfully produced the material commonly used on frames.11 Its use in Britain can be traced from small scale adornments on carved wood frames, through mimicry of carving, to a fuller realisation of the plastic qualities of the material with the creation of ornament unrealisable in carved wood. Some carvers continued in the trade by producing the carved moulds needed to press composition. These were expensive to produce and required great skill.

Composition frames from the first third of the nineteenth century have been viewed as indicative of a decline in the quality of frame making and craft practice in general.12 Later in the century, Charles Lock Eastlake, Keeper and first Director of the National Gallery spoke for many when he dismissed composition as ‘rococo scrolls and tortuous nonentities … chopped out by the dozen out of the meanest material’.13 An alternative interpretation of such frames might be that they are more eclectic or individualistic. The nature of the manufacturing process whereby moulds are endlessly reused in novel combinations led to richly decorated frames that reflected a range of individual budgets. It also allowed the full expression of the frame-maker’s artistic ingenuity, moving between re-interpretations in composition of the styles of earlier centuries and the creation of novel designs. The nature of composition ornament itself, however, with its self-destructive vulnerability to changes in temperature and humidity – particularly where poorer quality materials were used – led to the speedy deterioration in the appearance of some frames which was remarked upon at the time.14 Consequently, there was a wide-scale removal and destruction of many original composition frames.

Turner, Constable and frame makers around 1830

Artists themselves varied in the degree that they cared about frames but Constable and Turner certainly did.15 The small, closely connected art world of the early nineteenth century is evidenced by the frame maker Allen Woodburn – he made frames for both Turner and Constable, and was also friends with the latter.16 By 1831, artists exhibiting their work at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition were allowed much greater freedom with their frame choices. Before the turn of the century, the Academy had encouraged or enforced a policy of thin, simple, undecorated frames that could be hung edge to edge.17 Constable himself complained of the later relaxation of policy because it made the job of the hanging committee much harder.18 Frames became grander precisely to attract attention. Turner continued with versions of the deep scotia frames he had always favoured; in these frames a concave hollow form leads your eye to the edge of the painting. Constable chose ‘fairly conventional’ frames of the period.19 It appears the price of the frame was a significant portion of the combined price of painting and frame – one frame around a Constable painting in 1825 cost twenty pounds out of the total price of seventy-five guineas.20 Unlike Turner, Constable does not seem to have had a favoured pattern or profile and surviving frames do not allow us to draw many conclusions.

The rococo frame fitted to Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows at accession

At acquisition, the woodwork on the reverse of the frame was joined over the mitres (corners). The top rail had several old exhibition labels revealing a history of exhibition loans from the twentieth century. This earlier build-up was removed and a stronger one remade to enable the fitting of glazing.21 Beneath this removed material a part of a frame label was revealed which read: ‘H M Page, carver gilder … Manufacturer’. Harcourt Master Page (1823–1867) was a ‘looking glass maker’ in Coventry Street, London.22 This label does not necessarily mean Page made the frame, only that it passed through his workshop and predates his death. It must therefore have had a longer period of use than at first realised, perhaps even in Constable’s lifetime if it is of eighteenth century provenance rather than later neo-rococo. The frame is far more likely than first thought to be a genuine eighteenth-century rococo frame that went through several alterations.

Fig.3

The handwritten label on the frame of Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, found beneath the upper line of woodwork following its removal

Photo: Tate Conservation

© Tate

Fig.4

A detail of a corner of the old frame on Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows exhibited 1831 with the upper layer of wood from the build-up removed revealing the altered mitre keys beneath

Photo: Tate Conservation

© Tate

Another smaller, handwritten label with significant tears was also revealed (fig.3). What can still be made out says ‘[D?]avid, Wife, Bengal, allo….cy’, suggesting the frame was re-used from another artwork. This re-use may be confirmed by the way the keys securing the mitre are cut and do not meet, showing that the frame was cut down from originally larger dimensions (fig.4).23 The image also indicates a colour change on the back of the ornamentation around the corner, showing that changes have been made. These alterations must predate the earliest exhibition label so are at least pre-Second World War.24 The result is that we have a frame biography that indicates the frame is older than we first thought but has been re-used from another painting.

Validity of and approaches to reframing

It seems that the original display context of the frame is unknown and it is unlikely that a collector in Constable’s lifetime would have chosen it – collectors typically chose frame makers contemporaneous to the artists, or else the artists themselves organised the framing for clients. The frame does, however, connect with a history of reframing Constable’s paintings.25 Tate and other collections have large paintings by Constable reframed in English carved frames of the mid-eighteenth century of a type commonly described as ‘centre and corner’; these have cartouches of projecting ornament, typically composed of swags, acanthus leaf or scallop shell motifs across the mitres and at the centre of each rail often with the addition at their middle points of carved flowers.26 These frames are highly valued, and the choice may have come down to Constable’s recognition as an English painter increasingly esteemed throughout the nineteenth century, for whom an equally valued English frame was most appropriate.27 This, however, would be simplistic – these frames would have been around fifty to seventy years out of date by the time Constable was painting large canvases. Another notable choice for Constable works has been early twentieth century Parisian carved re-interpretations of styles derived from French historical sources.28 These reflect the influence of the art dealer Joseph Duveen who sold extensively to the American owners of late nineteenth century Belle Époque mansions.29 The conservator Gerry Alabone has discussed an example at Tate where even the compromised state of the ‘present anachronistic frame’ was accepted as part of a wider context, by revealing something about the evolving appreciation of Constable’s paintings; it was argued that the frame should be retained since even a researched replica ‘would not necessarily have preferable meaning for the painting and certainly much would be selectively forgotten’.30 So if in that case it was decided that the frame should remain, what are the criteria that justified the removal of the frame from Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows? What were the options for replacing it and how were they resolved?

One solution might have been to acquire a ‘period frame’, equivalent in date and origin to the painting. Peter Schade, Head of Framing at the National Gallery in London, has expressed that the purpose of reframing using period frames is not to recreate entirely the original display but to create a harmony between painting and frame and between pairings within one gallery.31 The choice to use/re-use a contemporaneous frame prioritises material authenticity – that it is as old as the picture – and an aspect of aesthetic authenticity – that it should appear as old as the picture. However, finding an appropriate period composition frame would have been difficult as there are relatively few museum-quality examples available for re-use.

Instead it was decided to give precedence to the contemporary enjoyment and display of a highly significant addition to the Tate collection above retention of a frame that represents an earlier moment in its presentation and appreciation. If the display were in a historic property rather than a museum, the decision may have been different. It can be argued that by not undertaking a limited treatment for aesthetic ends to the rococo frame itself, this earlier moment in the biography of the painting is being retained unaltered. The frame will be stored and at some future date the frame could be reunited with the painting. The belief in retention for its own sake has been criticised as an exercise that fetishises objects when in fact the practice of cultural heritage involves replacement as well as retention.32

The decision was taken to make a ‘replica frame’. The use here of the term ‘replica’ is intended to imply that the frame would be as far as possible a facsimile of a given example. A replica is also distinct from a ‘reproduction’, which suggests a frame in the manner of a given model or type. The replica may be a copy of a contemporaneous frame around another artwork or one that is realised from a full appreciation of the biography of the artist’s framing. This narrative is constituted from what an artist may have expressed, of the artist’s connections to frame makers or a knowledge of first framings. This fuller understanding of decorative art history and of framing is necessary to avoid exercising solely subjective criteria, though subjectivity cannot be excluded. The replica frame will inevitably reflect the period of its creation in ways not immediately identifiable. This could be the integration of the build-up with the ornamental aspect of the frame, rather than it being added on subsequently; it could be the definition of the pressed ornament; most obviously it could be the style of toning applied to the gilded surface to reduce the glare of newly ‘laid’ gold; or else the pressed composition might crack or distort less than that on a period frame, since it will only have existed in a museum where the conditions are stable. However, conservator Salvador Muñoz-Viñas has argued that creative practice is a legitimate, realisable and even a positive solution for particular conservation problems: ‘True re-creations are not possible, but pure creations are, and there is no reason why conservation should deny itself that possibility’.33 An honest explanation to visitors of why and how such a contemporary intervention has been undertaken is more informative than the pretence that a randomly purchased frame altered to fit the work is somehow more original because some of its material may be believed to be of the same age as the painting.

Potential models for replication

Fig.5

John Constable

A Boat Passing a Lock 1926

© Royal Academy of Arts, London

Fig.6

Two details of the frame around John Constable’s A Boat Passing a Lock 1826

© Royal Academy of Arts, London

Most larger paintings by Constable have been reframed, as previously explained. One frame thought to be an original Constable choice is that of the smaller work The Cottage in a Cornfield (Victoria and Albert Museum, London), dated 1817 but reworked in 1833 when it was shown at the Royal Academy. A label formerly on the reverse of the frame had both Constable’s handwriting and traces of his paint.34 Otherwise the frame is a conventional composition frame ornamentally typical for the period. When looking for a potential model for the reframing of Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, the most accessible larger frame dating to around 1831 was that of A Boat Passing a Lock 1826 (fig.5), which Constable gave to the Royal Academy in 1829 as his Diploma work on being elected a full Academician. There is no documentation at the Academy to prove the frame is Constable’s choice. The decorative language (fig.6) is like that on the small frame on The Cottage in a Cornfield but the frame has an ornamented addition along the outer back edge. The painting is fitted with slips, lengths of wood painted black and fitted into the frame which may disguise damage to the edges of a painting or the fact that it does not entirely fit the frame. This might suggest the frame and painting are not an original pairing. However, this frame was selected as a model to copy because it satisfied several criteria: it was certainly of the period; it may represent a Constable choice; it is ornamentally related to a known Constable choice; and, crucially, it was capable of being copied.

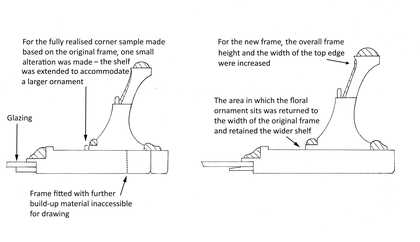

Fig.7

Cross section drawings by the author of the frame around John Constable’s A Boat Passing a Lock 1826 (left) and the design for the new Tate frame for Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (right)

Permission to make the left-hand drawing courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts, London

© Tate

Fig.8

Detail of the corner of the new frame, showing construction of the rail with the build-up and the mitre key cut into a slot on the reverse of the frame, as well as a section of pressed ornament

Photo: Adrian Moore

© Tate

Fig.9

Photograph of a corner of the new frame, showing the application of red bole in preparation for gilding

Photo: Adrian Moore

© Tate

At Tate, the practice of making replica frames has as far as possible followed the copying of a given model. First, a full-size profile drawing is made of the existing frame’s cross section. Following this design, a corner sample is reproduced by wood machining and hand finished. In this case, the sample was made with a single alteration, and after setting the sample against the painting itself, further alterations were made to the final fully realised frame design (fig.7). This is then painted with up to twenty layers of whitening (or gesso) and smoothed before cutting the mitres and joining the frame – traditionally with keys across the reverse of the mitres (fig.8). Afterwards the frame is painted with pigmented boles, mixtures of thin animal glue with clays and alternative pigments (fig.9).35 Once laid over the whitening or gesso, the boles provide a base for gilding, typically yellow beneath oil gilding and plum or red beneath water gilding. Once sufficient time has passed the frame is toned, which might simply be a coat of gilder’s ormolu – a thin animal glue size with shellac. When making a new frame for an older painting, the bright new gilding needs to be toned in order not to distract from an age-darkened painting.

Fig.10

Detail of the corner of the new frame, showing the pressed ornamentation

Photo: Adrian Moore

© Tate

It was identified that nine different moulds would be needed to replicate the ornamentation of the Royal Academy frame but we were unable to take direct impressions from the original frame to use as a basis for new moulds. Four original boxwood moulds were sourced: one exactly replicated the back-edge ornament of ‘pears between leaves’, illustrated in fig.8 in a raw state prior to the application of the bole; the other three were close approximations to the ornament on the frame being copied. Consequently, five reverse moulds had to be made and the best material for doing this was polyester resin and glass fibre. Composition ornament pressed out under pressure from a mould placed in a book press gives the most consistent result with the finest detail. Soft, more flexible silicon rubbers cannot be used to make moulds from which to produce composition. Hard rubbers on the other hand are liable to crack from repeated efforts to extract the pressed composition from the mould. The making of two polyester resin moulds began with taking an impression from original ornament using a dental putty, one a front edge ornament on another ‘Constable’ frame at Tate.36 This impression was then used to cast positives in plaster which were brought together into a twelve inch (304.8 mm) line. A new negative in silicon rubber was taken from which a new plaster could be cast. This negative was also ‘improved’, raised by a millimetre or so to take into account both past and subsequent shrinkage and in its turn used as the sacrificial positive from which to take the new resin mould. The biggest compromise was that the first impression was taken of material already shrunken and distorted by age. Even though this can be ‘improved’, any newly pressed composition is seldom the same as the smooth material typically pressed from well preserved original moulds, but something that reflects the aging process.37 Further reverse carved moulds were made using positives of newly carved lime to replicate the original ornament. As the top edge leaf ornament is a motif running both to the left and right, this means two limewood positives were needed for two separate moulds. The distinctive corner ornament also required a positive carved from lime by a wood carver working from drawings and photographs. It was important that the carver should carve in such a way as to resemble composition ornament – undercuts would make it look like carved wood and less like pressed composition. The results of the process are visible in the corner detail (fig.10).38

Fig.11

John Constable

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows exhibited 1831 with the new frame

Tate

The appearance of the new frame is necessarily toned to accommodate its relationship with the painting. Unlike a picture frame, a conserved piece of furniture can stand on its own terms – when on display, for example, no one will object to it being brightly gilded. The concern for the aesthetics of aging and a requirement for an authentic appearance results in toning of the already old and distressing of the new – ‘the artifice of decay’.39 For the replica frame, its success will be gauged by how well it presents the picture, the appropriateness of its historical period, the quality of its making and the subtlety of its complementary toning, all while remaining self-effacing.

It can be understood from the description above that the development of any replica frame – and this one in particular – involves a certain amount of approximation ornamentally, although the materials used are authentic to the period. The frame becomes a creative museum hybrid: a ‘reconstructive restoration’ that aims to influence the viewer’s perceptual experience of the painting.40 The two frames – the new one (fig.11) and the rococo one – offer different concepts of the authentic to Constable’s painting. Both frames have historical value – the older as part of the biography of the painting and the newer providing a more likely impression of the original setting.41 However, the new frame offers the museum the opportunity to show the parity of esteem accorded to Constable and Turner in the collection by the quality of the reframing of both paintings. While the display in 2018–19 at Tate Britain juxtaposed the two works in a recreation of their appearance side-by-side in the 1831 Royal Academy, it is also hoped that in the future the Constable in its new frame may fit more comfortably within the chronological displays.

In the spirit of the work

Frames have a dual role (as artefact and tool) and understandably in an art gallery they are less understood and valued in their unequal relationship with the paintings they display. The aim of this paper has been to show how through an understanding of the biography of an artist’s framing practices, a resolution might be found for a painting needing a frame. In this instance, of course the painting already had a frame, but one that was not thought to function adequately if both aesthetic and historical factors were taken into account. Sourcing a period frame would have been one solution but the result can only be based on what is available, limiting the aesthetic and historical benefit. Whether a period frame is purchased and altered, or a new frame created, it will always reflect to some degree the moment of its realisation. Aside from this inevitability, retaining the idea of what was significant at any given moment admits that neither the painting nor the manner of its display can be maintained in perpetual and unfaltering stasis. The retention of the previous frame may have revealed the opinions of a late nineteenth century owner, but this aspect of the painting’s provenance could only be tenuously inferred by a contemporary viewer. The type of frame that might have been commissioned from contemporary frame makers by Constable himself or the painting’s first owner was deemed to add more contextual value to the viewer’s experience of the painting. For the Constable frame, a craft tradition was pursued based on research with an achievable outcome. The result is that, as curator Elizabeth Easton observed of another frame produced through similar processes, ‘it’s handmade. It doesn’t pretend to be nineteenth century but it’s completely in the spirit of the work’.42 A collaboration between conservation and curation has been essential to the success of the reframing project. In the end, the greatest significance is that the painting should be displayed in a manner that enables the widest possible appreciation of this significant Constable work.