Novel combinations of materials in contemporary artworks present new challenges to conservation, in part because of the lack of experience and research regarding how these materials might interact with each other and change over time. In some cases, paintings may appear within the context of an installation, like Mark Rothko’s Seagram Murals 1958–9 (Tate T01031 and T01163–T01170) or Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross 1958–66 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Sequences of paintings which together function as a unified work broaden the range of considerations relevant to their conservation. This paper examines some of the elephant dung and resin paintings Chris Ofili made in the 1990s and early 2000s, and considers their care and display for the future. In order to understand these works better, mock-ups were made with Ofili’s full range of materials and these were used to assess vulnerabilities, particularly sensitivity to light, heat and the handling necessary to make them accessible for public display, along with other potential contributions to colour change. This information is considered here in relation to the rhythm of museum display allowing for a more reflective and evidence-based, rather than rule-based, approach to their conservation.

The Upper Room

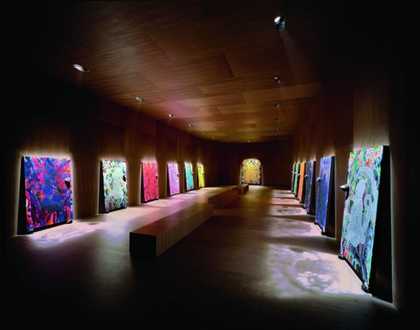

Fig.1

Chris Ofili

The Upper Room 1999–2002

Installation view at Tate Britain, London, 2005

Oil paint, acrylic paint, glitter, graphite, pen, elephant dung, polyester resin and map pins on 13 canvases

Support, each: 1832 x 1228 mm, support: 2442 x 1830 mm

Tate T11925

© Chris Ofili

Photo © Tate

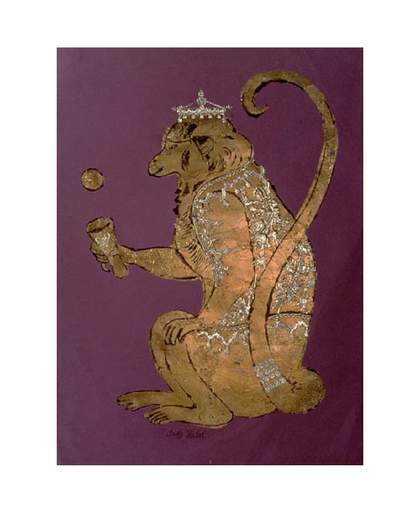

When installed, Chris Ofili’s The Upper Room 1999–2002 (fig.1) is accessed via a long, dimly lit corridor that leads the visitor to the room named in the title. Unprepared for what might be found at the end of the corridor, the visitor turns into an enclosed room clad on all sides with walnut wood panelling which gives off a distinctive spicy smell. Inside, visitors are free to wander around the space and soak up the atmosphere as they might a chapel or highly charged environment such as the Rothko Chapel in Houston. Thirteen paintings are propped against the wall, each canvas resting on two balls of elephant dung. The paintings’ surfaces are highly decorated with glitter and closely spaced painted dots, and each one radiates a dominant bright colour: orange, purple, grey, yellow, green, red, black, turquoise, brown, pink, blue and white. Twelve of the paintings are just under two metres high and bear the same image of a monkey posing in profile within a jungle scene (see, for instance, Mono Gris (Grey Monkey); fig.2). The composition is based on a 1950s collage by Andy Warhol in which a monkey, with his tail curled up in the air, plays a cup and ball game (fig.3).1 In Ofili’s paintings the ball is a piece of elephant dung adhered to the canvas above the painted cup. The paintings are positioned along the two long opposing walls of the room so that the monkeys look towards the thirteenth painting on the end wall, which depicts a larger gold monkey staring directly out at the viewer. The larger canvas is placed at the head of the room, much like an altarpiece, while the other twelve are arranged around it in a way that is suggestive of Christ flanked by his disciples at the Last Supper. There is no daylight in the space; instead each painting is dramatically lit using spotlights discreetly set into the ceiling, their warm tones bringing out the jewel-like quality of the resin coated painted surfaces. The lighting has been carefully designed to create coloured reflections of the monkey motif on the polished floor in front of each canvas, similar to the effect of stained glass windows. The installation was designed in collaboration with the British architect David Adjaye.

Fig.2

Chris Ofili

Mono Gris (Grey Monkey), from The Upper Room

Photo © Tate

Fig.3

Andy Warhol

Monkey 1950s

© Andy Warhol Foundation

Source: Traditional Fine Arts Organization

In 2005 The Upper Room entered Tate’s collection at which point Ofili gave clear instructions regarding the aesthetics of the display.2 Installation of the artwork was deemed possible at all of the Tate sites with the exception of Tate Liverpool, whose structural columns were, to the artist’s regret, considered too distracting to retain the integrity of the artwork. Ofili agreed that the hardwood panelling be treated with a fire retardant substance, that safety signage and benches for visitors could be placed within the room and that instead of physical barriers a gallery assistant could be stationed in the installation.3 The artist’s original concept was for visitors to approach the space by climbing a steep staircase before reaching an ‘upper’ room. This was realised on the work’s initial installation at the Victoria Miro Gallery in London for the 2002 exhibition Chris Ofili: Freedom One Day, but was not possible within any of the gallery spaces at Tate.4 An alternative corridor design was agreed upon, one that was just wide enough to allow for double wheelchair access.

The structure of the paintings

Discussing work accessioned into the Tate collection with contemporary artists is an activity that started in the 1980s and continues to reap benefits today. The gathering of knowledge through conservation interviews frequently takes place towards the end of an artist’s career, but in this case we were fortunate to discuss The Upper Room with Ofili in 2004, while his working practice was fresh in his mind.5 Disliking the general term ‘mixed media’, Ofili detailed the specific canvas, primer, graphite pencil, felt-tip pens, map pins, acrylic paints, oil paints and polyester resin that he used. Of interest to conservators were the materials he had replaced with ones that better suited his requirements. For example, he started using expandable wooden stretchers in favour of fixed aluminium strainers and he changed the brands of oil paint and acrylic gesso primer he had been using. He described projecting intricate designs derived from pattern books onto mirror-smooth, white-primed canvases and meticulously tracing them in pencil and felt-tip pen. He acknowledged that the artwork, originally conceived as a triptych, had had the potential to be monotonous to produce as it developed in scale. This was alleviated by using a freestyle approach to painting the foliage designs, altering them on the canvas to create more pleasing colour juxtapositions, or playing with effects such as scratching through layers to reveal different paint colours beneath.

Fig.4

Chris Ofili

Detail of Mono Turquisa (Turquoise Monkey) from The Upper Room, showing the white priming, graphite pencil design, acrylic paint of background foliage, drips of turquoise oil paint, dyed resin and dots of oil paint

Photo © Tate

From the surface of each of the thirteen paintings in The Upper Room protrudes a ball of elephant dung, a medium that Ofili incorporated into his art after experimenting with its use on paintings while attending the Pachipamwe International Artists’ Workshop in Zimbabwe in 1992.6 The dung balls he used for The Upper Room were sourced from London Zoo, until a tragic accident in which a keeper was killed led to the elephants being relocated to the more spacious grounds of Whipsnade Zoo in Bedfordshire. With the canvas resting on a horizontal plane the dung balls were positioned and polyester resin, dyed a different colour each time, was poured on top, coating the entire painting surface. In between resin pourings Ofili sprinkled glitter and, in the case of the gold monkey canvas, gold leaf, an idea that came from seeing gold-covered chocolates in Japan. On curing, the resin secured the dung balls in place. Once fully dry and with the canvases upright, the monkey image was projected onto the resin surfaces and the motif outlined and filled in with oil paint dots (fig.4). These were applied by removing the bristles of a paintbrush and using its ferrule – the metal part that usually holds the brush hairs in place – to create the dots. Rather than aboriginal art, the dotted paint application refers to an artistic practice found in prehistoric cave painting in Africa which Ofili saw when visiting the San caves in the Matobo Hills, Zimbabwe.7

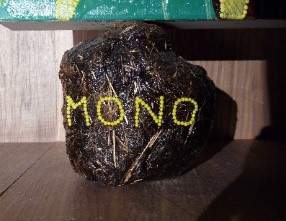

Fig.5

Chris Ofili

Detail of Mono Amarillo (Yellow Monkey) from The Upper Room, showing one of the dung ball supports bearing the title of the painting

Photo © Tate

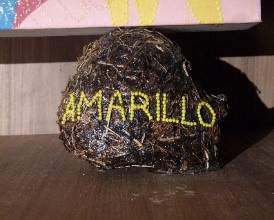

Fig.6

Chris Ofili

Detail of Mono Amarillo (Yellow Monkey) from The Upper Room, showing one of the dung ball supports bearing the title of the painting

Photo © Tate

To match the colour of its dyed resin coating, each monkey was painted in a single oil colour, save for the multi-coloured fingernails, toenails, beard and waistcoat buttons. The dung ball supports on which the canvases rest bear the title of each painting in coloured map pins. These titles are a play on the word ‘monochrome’, and consist of the Spanish word mono meaning monkey, followed by the painting’s colour reference – for instance Mono Amarillo, meaning ‘Yellow Monkey’ (figs.5 and 6). The idea for the Spanish titles derives from a visit the artist made to Cayo Santiago, Puerto Rico, a research field station at which rhesus macaque monkeys are studied.8

Conservation concerns

When asked in a 1997 interview if he had ever felt any pressure to ensure the physical stability of his paintings, Ofili replied: ‘I’ve done all that I can, all that I know. As far as I’m prepared to go to ensure it will be ok. But obviously I’m using a combination of materials that we don’t know much about’.9 For traditional oil paintings, conservators benefit from decades of research into the chemistry and ageing properties of their constituent materials. While we had good knowledge of Ofili’s materials in isolation, we had little knowledge of how their combinations might behave and change over time. Having collected information from the artist, studies were designed to help understand the vulnerabilities of these extraordinary paintings. We sought evidence for how they might be packed, handled and displayed, in order to make them accessible to the public now and in the future.

The vulnerabilities to study fell into two distinct categories. Firstly, we wanted to understand the colour stability of the paintings both on exposure to light and during storage in the dark. Secondly, we wished to understand how liable the dung balls were to becoming detached, either due to their weight or due to an accidental blow.

The lighting that was such an integral part of the design of The Upper Room produced an illuminance of 1,000 lux, which is between five and seven times stronger than would normally be specified as appropriate gallery lighting for an artwork made from oil or acrylic paint. Limiting the artwork’s exposure to light would seem beneficial to reduce the fading of light-sensitive materials, such as felt-tip pen, as well as resin discolouration. However, this might not itself prevent all colour change, because the possibility existed that storing the paintings in the dark at typical room temperature could still lead to irreversible colour changes and chemical deterioration. If proven to occur, this would make regular display of the installation in the first decades of its existence the most appropriate option.

The halogen light selected by the artist, while low in ultraviolet light, generates a relatively large amount of heat.10 This can be problematic as it could raise the room temperature even in a large space, and many modern paints and coatings are already quite soft at typical room temperature.11 When dust from the building and fibres, hair and skin flakes shed by visitors land on the surface, they can sink in and become entrapped. Furthermore, Ofili had commissioned a paint manufacturer to make gold paint incorporating mica – a silicate mineral that has a shiny appearance similar to glitter – to make the surface appear pearlescent, which turned out to be slow to form a dry paint film, leaving Mono Oro (Gold Monkey) particularly vulnerable to dust retention early in its lifetime.

Fig.7

Chris Ofili

Detail of Mono Naranja (Orange Monkey) from The Upper Room, showing the attached elephant dung ball

Photo © Tate

Mono Naranja (Orange Monkey) had a different issue: it was noticed on acquisition that its dung ball drooped forwards (fig.7). It was unclear whether this was due to its natural asymmetrical shape or the result of forces exerted by the ball’s weight gradually distorting it. We considered ways to reinforce the attachment of the dung balls to the canvases but all ideas were rejected on the grounds that intervention meant risking damage. We were also aware of Ofili’s thoughts on the subject. In an interview he wondered:

[W]ould I agree to somebody putting a bolt through the back of the painting to support the elephant dung? … I wouldn’t agree to that because for me it’s part of the charm that you can’t quite work out how it’s held on the surface, and if you looked round the back and saw this bolt running through it then it takes the charm away. It’s supposed to be this kind of magic thing.12

In the end it was thought best to monitor change in the conformation of the dung ball on Mono Naranja through imaging. Since acquisition in 2005, several conservation treatments to re-attach partially or fully detached dung balls have been carried out on similar artwork in private conservation practice. These treatments have shown that stabilising dung balls on Ofili’s paintings may not require the major interventions first discussed at Tate, and this would certainly influence our approach should treatment be deemed necessary in the future.

Fig.8

Sigmar Polke

Untitled (Triptych) 2002

Polyester resin and acrylic paint on fabric

Tate T11855

© The estate of Sigmar Polke/DACS 2018

Photo © Tate

Fig.9

Sigmar Polke

Detail of Untitled (Triptych) showing branched cracks in the resin coating

Photo © Tate

Fig.10

Chris Ofili

Detail of Mono Azul (Blue Monkey) from The Upper Room, showing circular fractures in the resin coating

Photo © Tate

To get a sense of changes in the condition of polyester resin coatings as a result of age, other paintings in the Tate collection were examined for cracks, fractures and delamination between canvas and resin. Made at a similar time to The Upper Room, Sigmar Polke’s Untitled (Triptych) 2002 (fig.8) employs resin on a transparent fabric to act as the surface for a painted image. Examination of sixteen paintings by Polke and Ofili revealed very few defects and all were minor faults that may have been formed during or soon after fabrication (figs.9 and 10). The possibility remained, however, that these existing faults could develop in response to repeated handling, vibration and shock.

For the first display of The Upper Room at Tate in 2005, conservators recommended measures to minimise risks to the artwork while on display. These included using lower power light bulbs to reduce heating and to limit colour change (while retaining the monkey reflections on the floor) and signage outside the room to encourage the public not to touch the highly attractive painting surfaces. Four years later, the paintings, which had meanwhile been in storage in the dark, were again closely examined in preparation for Ofili’s mid-career solo exhibition at Tate, which was to open in early 2010. While the paintings showed no obvious signs of deterioration it was apparent that a more scientific approach to measuring change was needed, rather than relying on visual memory or photography. Moreover, with the prospect of other elephant dung/resin paintings travelling to London for the exhibition, we were obliged to recommend methods of handling, transport and storage to lenders that would mitigate risk.

Using and understanding Ofili’s materials

The obvious step to gain a better understanding of the vulnerabilities of paintings made from non-traditional artists’ materials is to make mock-ups and subject them to greater stresses than they would meet within a display period. To this end we sourced products used by Ofili, starting with the most obscure and seemingly least attainable in the UK. We were delighted when Whipsnade Zoo agreed to supply us with five elephant dung balls. On grounds of historical accuracy, it was fitting that they came from Mia, the elephant whose dung Ofili had used in the 1990s. Mia’s birth in the UK, her diet and her healthy lifestyle reduced potential biohazards and helped sanction the use of her dung balls for research purposes on Tate premises. Once dry, the dung balls were flushed with white spirits to kill any remaining organisms and were soaked in resin according to the artist’s practice. Ofili’s other materials – primer, graphite pencil, felt-tip pens, map pins, acrylic paints, oil paints and polyester resin – were readily available with sufficient information about their constituents from the manufacturer, so little materials analysis was necessary. However, by 2009 the type of primed canvas Ofili had used for The Upper Room was found to be discontinued. We were fortunate that the artist had retained some offcuts and was willing to donate them to the study.

Fig.11

Chris Ofili

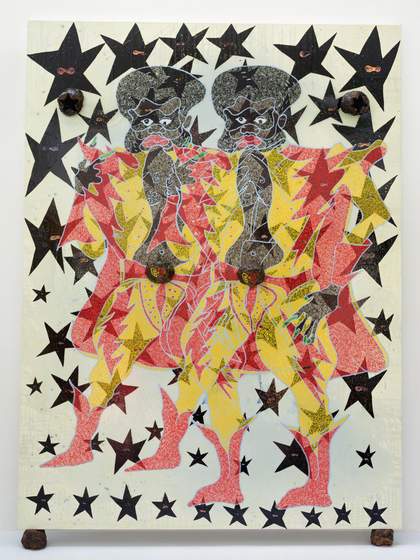

Double Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars 1997

Oil paint, acrylic paint, printed paper, glitter, map pins, polyester resin and elephant dung on canvas

Tate T07345

© Chris Ofili

Photo © Tate

Fig.12

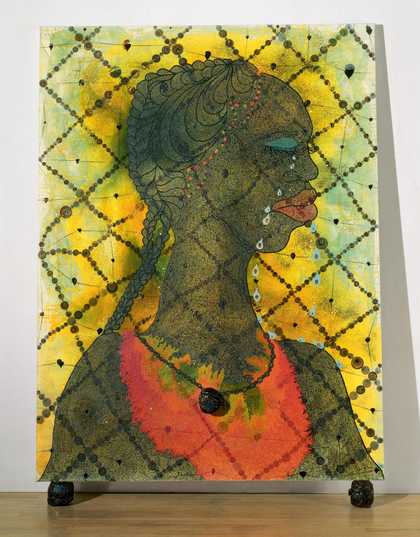

Chris Ofili

No Woman, No Cry 1998

Oil paint, acrylic paint, graphite, polyester resin, printed paper, glitter, map pins and elephant dung on canvas

Tate T07502

© Chris Ofili

Photo © Tate

Mock-ups were made with the artist’s materials in three sizes to use for three distinct purposes:

- Five 20 x 25 cm primed canvases were painted out with stripes of primer, fifteen examples of acrylic paint, five examples of oil paint and two examples of felt-tip pen. Collage elements cut from magazines and phosphorescent paint medium13 were also applied to the canvases because Ofili has used them on other dung ball/resin paintings in the Tate collection: Double Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars 1997 (fig.11) and No Woman, No Cry 1998 (fig.12). Three test canvases were coated with transparent polyester resin, one with resin dyed to an amber colour, and one left uncoated. Three of the canvases were produced for accelerated ageing tests in a light box and two to measure dust pickup in storage. As a visual indicator of colour change, aluminium foil was used to mask a narrow strip of each test canvas (although this assumed that the protected colours do not alter over time).

- Four 65 x 95 cm canvases were primed, painted and had a centrally positioned dung ball secured to them with a coating of transparent polyester resin. These canvases were made for drop tests.

- One 183 x 122 cm canvas was made, an exact replica of Mono Rosa (Pink Monkey), save for the Tate logo added in oil paint to distinguish it (figs.13 and 14). This canvas was made to help understand the artist’s working practice and to be kept as an archival resource should tests on aged material become necessary in the future.

Fig.13

Chris Ofili

Mono Rosa (Pink Monkey) from The Upper Room

Photo © Tate

Fig.14

Conservator Natasha Walker applying the Tate logo in oil paint dots to the full-scale mock-up of Mono Rosa (Pink Monkey) to distinguish it from the original

Photo © Tate

Fig.15

Two of the striped test panels, the left with amber-dyed resin and the right with undyed resin, during accelerated ageing

Photo © Tate

The aim of carrying out accelerated light ageing was to measure the performance of Ofili’s materials in response to light and elevated temperatures over a known timeframe. The light box, an early design made in 1998, was equipped with UV filtered fluorescent tubes which provided the increased temperature in a small space – about 10˚C above room temperature – to mimic the environment of The Upper Room, or probably a somewhat harsher one (fig.15).14 A light box was used because the acrylics and most of the oil paints were likely to be individually very resistant to fading, so long periods of continuous accelerated ageing were needed, ultimately totalling twenty-eight months at 12,000 lux. This appears to give an acceleration factor of 12 over Ofili’s lighting, but display lighting would only be used for 10 hours per day, every day, increasing the factor to 30. The light ageing thus mimicked about 70 years’ worth of cumulative display.

Fig.16

Natasha Walker taking colour measurements

Photo © Tate

Reproducible and reliable colour specification can be done with a hand-held spectrophotometer, on a spot that is 3 mm in diameter (fig.16).15 The results are expressed in terms of three different quantities: red-green representing fading of colourant, yellow-blue representing yellowness due to chemical deterioration and/or loss of blue colour, and light-dark indicating dulling due to dust retention. The calculation of the colour difference between a coloured surface before ageing and a coloured surface after ageing can take account of the viewing conditions and lighting type. Sometimes it is necessary to make many hundreds of colour measurements to prove that nothing has changed. This method is more sensitive than human vision and also enables the type as well as the extent of colour change to be described, making it possible to work out in what respect the materials have changed.

Tate specification transit frames, of the type used to protect display frames and unframed paintings when they are being moved between sites, were made to store two of the small test canvases. One was wrapped in black polythene to mimic long-term storage in a wooden crate and the build-up of volatile products from wood and adhesives that this implies, while the other was left unwrapped, to act as a visual indicator of dust pickup and its effect on appearance.

There were two objectives for the drop tests. The first was to assess the strength of the dung ball’s attachment to the canvas by dropping the canvases at progressive heights until the dung ball detached. Drop tests carried out with mock-up canvases secured in transit frames would additionally gauge the protection offered by the transit frame and more closely mimic a potential accident during handling or transportation of a Tate painting. Once the dung balls were detached, the mock-ups could then be used to trial methods of dung ball reattachment. Drop tests were not realised in 2009 because it was felt that the response of the newly fabricated dung ball/resin test canvases would not closely mirror that of an artwork that was by then more than ten years old. Along with the full-size replica, these mock-ups were accessioned into Tate’s conservation archive to use for colour measurement, drop testing or other assessments, should they become necessary in the future. In 2016 our foresight in making the mock-ups proved key to a treatment carried out by conservators in private practice following an accident when a dung ball was knocked clean off its canvas. One of the mock-ups, by then naturally aged for seven years, was maltreated, mimicking the accident, until its dung ball detached. The mock-up was then used to trial reattachment of its dung ball, to fill sites of resin loss and to excavate and refill new channels in the resin.16

Results

Colour measurements of the small test canvases were taken at four-month intervals. The second readings, taken at eight months, revealed that the amber-dyed polyester resin undergoing accelerated ageing was not resistant to fading. In response, we made four new test canvases so that the study included resin tinted with each of the commercially available dyes Ofili had used (green, yellow, blue, red and amber – which is the full product range). Half of each canvas was masked to measure colour change in the dark – albeit at elevated room temperature – before being added to the light box for comparable ageing.

There was no discernible colour change in the dyed resins kept in the dark for twenty months at elevated room temperature, but after this time the yellow dye began to lose colour perceptibly. This was not a greatly accelerated test, possibly only by a factor of 2–4 due to increased temperature. As such, the finding that a change might occur after only a few years of typical display conditions for The Upper Room gave cause for concern.

Based on the known chemistry of the other materials tested, we were also concerned that the titanium white combined with many of the stable, modern, organic colourants in the oil and acrylic paints would drastically reduce their stability to light, and that the polyester resin would have reacted chemically with some of these paints before it set, leading to a yellow appearance for some colours. Any of these scenarios could lead to great visual changes to The Upper Room paintings, either through loss of a key colour from many canvases or through patchy yellowing of all of them.

Fig.17

Dyed polyester resin test panels after two years of light ageing

Photo © Tate

In fact, the only significant change measured was in the dyed polyester resin. Fig.17 shows dyed polyester resin test panels after two years of light ageing. The lower halves, having been protected from light, still show the original colour. Of these, the yellow dye showed the greatest colour loss, followed by the red and amber ones, the blue being unchanged and the green one virtually so. Mixtures of these dyes would tend to lose colour as rapidly as the most light sensitive component, leading to significant shifts in tonality that could potentially disrupt Ofili’s carefully planned colour scheme. If one assumes that light ageing successfully mimics real gallery conditions (a position rather difficult to justify chemically for all materials, if they are reacting together), then noticeable loss of colour would be expected in large areas of some of the canvases of The Upper Room after ten to twelve years of cumulative display. As accelerated light ageing of the replicas continued, the colour loss in some dyed resins looked patchy where the thickness of the resin varied – as can be seen in the orange resin in fig.17.17

Some acrylic paints with pure, deep colours were unchanged, as was the white priming on the canvas, while some colours that were lightened with titanium white did indeed lose colour as predicted after only eight months of ageing, diarylamide yellow with titanium white being the worst. This colourant would have good or excellent light stability in an acrylic paint when not combined with titanium white. Paint stripes on the two test canvases in transit frames, undergoing natural rather than accelerated ageing, altered much less. A few colours changed perceptibly in the one enclosed in black polythene, simulating dark storage, already described as being at greater risk of alteration. These differences, however, were all far less dramatic than the colour change in the warm-toned dyed resins.

The effects of dirt pickup were just visible and measureable when comparing resin-coated areas under and next to the areas masked with aluminium foil after ageing. Dirt pickup and retention was a concern as it dulls the surface of the paintings. It is known from studies in other museums that dust capture is worst within a metre or so of the areas in which gallery visitors can move around.18

The phosphorescent medium, used as an under layer for Double Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars and in an inscription on No Woman, No Cry, normally glows in the dark following exposure to light. Accelerated ageing showed it lost some colour and became more yellow over time, a result not unexpected based on its chemistry. It is likely that accumulated light exposure would eventually render the medium either invisible (the more likely option) or else permanently visible in all lighting conditions. The magazine collage elements also used on both these paintings faded visibly during light ageing although their printing was too uneven for accurate repeat colour measurements to be made.

Conclusion

With the benefit of study we know that the dyed polyester resin is the most vulnerable element of The Upper Room paintings. Since it was created, the artwork has been displayed three times for a total of twenty months. Colour measurements following the last two of these periods revealed colour loss that would be just perceptible in side-by-side comparison19 for three of the canvases: Mono Morado (Purple Monkey), Mono Negro (Black Monkey) and Mono Marron (Brown Monkey), all of which appear to be mixtures of the five dyes in polyester resin. This study has enabled us to say with confidence that The Upper Room and works by Ofili in similar materials are far more light sensitive than a simple listing of their constituent materials might suggest.

Fig.18

Detail from the right shoulder of the sitter in No Woman, No Cry, showing amber and turquoise coloured polyester resin of various thicknesses, collage discs inspired by the circular patterns produced by a Spirograph, and detailed drawing in graphite pencil

Photo © Tate

Now that we understand better the vulnerabilities of The Upper Room, we can balance protection and access for the other Ofili elephant dung/resin paintings in the Tate collection. No Woman, No Cry is a painting very frequently requested for display at Tate sites and for loan to galleries worldwide. This is undoubtedly because of the strong message it carries20 and perhaps because it does not have expensive installation costs, in contrast to The Upper Room. No Woman, No Cry has substantial areas of amber as well as pale turquoise-coloured resin. The painting has been monitored with colour measurements of these areas over twenty months of display at different Tate sites. With no specific lighting requirement given by the artist, it is always displayed at 80 lux rather than the 200 lux recommended for oil paintings. Already the amber resin has been found to lose some colour, while the turquoise-coloured resin has not, probably because it contains the more stable green or blue resin dye (fig.18). The same behaviour was seen in the mock-ups. Colour change is not yet noticeable with the human eye even on close examination, but if a side-by-side comparison were possible, then these changes would be fairly obvious. The un-dyed resin has grown slightly darker, indicating dust retention even after gentle brushing, and is fractionally yellower. These are predictable changes too for this material, and they are smaller than the loss of colour from the amber resin.

Fifteen years after they were made, The Upper Room paintings show no obvious signs of mechanical failure. The drooping dung ball on Mono Naranja (Orange Monkey), and the circular fractures in the resin of Mono Azul (Blue Monkey) appear unaltered. After eight years of natural ageing the replica and mock-ups are equally unchanged. They have not been required for pre-treatment tests following damage to a Tate collection painting, while we are aware of propagated cracks and the detachment of dung balls from three Ofili dung ball/resin paintings in other collections. This tends to suggest that mechanical failure is controllable and largely preventable with careful handling, storage in transit frames and customised packing procedures in place. Knowledge gained from the study will determine the ways that Tate displays and stores Ofili’s dung ball/resin canvases in the future, in order to slow down changes as much as possible.