There is no place in Europe like Rome for the number of artists of different nations, there is no place where there is so much ambition of who shall produce the finest works – this concentration for fame keeps up the art and good taste. Here art is not a money making trade. You should make an effort to come here and we would go to the Vatican together.1

When John Gibson penned this letter to his friend and former fellow pupil John Barber Crouchley in early May 1837, his primary place of residence and the centre of his sculptural practice was firmly established in Rome, with his career on a firm upward trajectory towards success and recognition. By contrast, Crouchley, who had been prevented by his father from travelling abroad with Gibson when he left Liverpool in 1817, saw his ambitions as a sculptor subsequently fade.2 Little remains of his artistic practice other than drawings and sketches; his only surviving sculptural work is an early wax portrait of Gibson in the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, seemingly kept because of its subject rather than its authorship.3 Over an extended period Gibson would keep this longstanding friend updated with detailed letters providing news of his own successes and the artistic environment in Rome. Presumably this was to continue a firm friendship from a distance, and partly in the hope that this might spur him into making a visit to Rome, as the exhortation to ‘make an effort’ implies: an invitation that appears never to have been taken up.

Fig.1

John Gibson

Mars and Cupid 1825

Sculpture Gallery, Chatsworth House

© Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees

Fig.2

John Gibson

The Meeting of Hero and Leander 1839–41

© Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees

The sculpture market that Gibson encountered in Rome during his long residency was fiercely competitive, its history littered with those who, despite their ambition and endeavour, were unable to build sufficiently strong patron bases and studio workshops in order to prosper.4 But Gibson’s success operating from this international sculpture ‘hub’ was not simply the result of his ability to ‘produce the finest works’ or of any driving ambition. He had the talent to manipulate the market to his advantage by maintaining knowledge of the competition alongside a skilful and nuanced exploitation of his patrons’ expectations. In this he needed no interlocutor such as the one employed by Francis Chantrey, arguably Gibson’s greatest rival in Britain during the 1830s, who from the outset used the skills of his foreman Allan Cunningham as promoter and spokesman to grow his fortune and reputation.5 Gibson, as his correspondence with Crouchley and others evidence, was clearly a consummate letter writer who had the ability by this means to play adeptly upon his patrons’ desires and fears, building trust and promoting his own work over that of others. It is this element of his professional career that will be considered here through the specific example of his dealings with his patron William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire. This relationship followed on from their first encounter in Rome during 1819 with the commission for Mars and Cupid 1825 (fig.1) and the later marble relief The Meeting of Hero and Leander (fig.2), commissioned in January 1839 and completed by 1841. Both were destined for a specific location, the Sculpture Gallery at Chatsworth; a new addition to the house where the 6th Duke’s collection of contemporary sculpture was displayed from 1834. When Gibson was executing the Chatsworth Hero and Leander he had achieved professional advancement and recognition, and weathered a series of unforeseen events in Italy and Britain that in 1837 directly threatened the British presence in Rome and the health of its sculpture market. He resolutely retained his studio workshop there while many of his less established fellow British sculptors were impelled to make crucial decisions over the optimum location for their future professional development.

The sculpture market in Rome

After the interruption of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15), artistic pilgrimages from Britain to the Italian states once more provided an ebb and flow of cultural tourism continuing according to season, society and epidemic. Shortly after Gibson’s arrival in Rome in October 1817, the poet Samuel Rogers estimated the post-war numbers of British tourists there to be in the region of 2,000, many of whom included on their itineraries visits to sculptors’ ateliers to spectate and sometimes to buy.6 There is a variety of evidence that shows the accessibility of sculptors’ studios in Rome to British visitors during this crucial post-war period, and this represented a highly important market for resident British sculptors.7 The knowledge and availability of these sites can be summarised by two ‘lists’ of sculptors in Rome complied at this time, one public and one private. These are indicative of the competition and the ground that Gibson had to cover in order to establish himself professionally. The first, published in the New Monthly Magazine in 1820, indicates the major sculptors’ studios but does not include Gibson’s name:

Canova/Thorwaldsen/Von Bystrom/Shadow Junior/‘The ingenious Carraresen’ (who runs Thorwaldsen’s studio in his absence)/Tenerani/Von Lannitz/Testanova [Trentanove?]/2 Spaniards/A Frenchman8

The second list, compiled by the 6th Duke of Devonshire during a visit that took place immediately after Antonio Canova’s death in 1822, similarly names Bertel Thorvaldsen and Johan Niclas Byström (Rudolf Schadow had died earlier that year), but also includes younger, fledgling sculptors such as Gibson, whose name is placed next to Thorvaldsen’s, with his Christian name given in Italian:

Alberto Torwaldsen/Giovanni Gibson/Cincinnato Baruzzi/Rinaldo Rinaldi/Adamo Tadolini/Pietro Trentanove/Campbell/Rennie/Wyatt/[Name crossed out]/Britrom Swede/Kessels Olandese/Albacini/Francesco Benaglia9

Fig.3

Bertel Thorvaldsen

Venus with an Apple 1821

Sculpture Gallery, Chatsworth House

© Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees

The 6th Duke, known for his ‘incurable extravagance’ where sculpture was concerned,10 commissioned works from all the sculptors listed by him in 1822, with the exception of Byström. His expenditure in doing so set him up as one of the major collectors of contemporary sculpture in Europe. Gibson had adeptly courted his patronage from their initial meeting in 1819 when the 6th Duke made his first visit to the city, staying there from 21 March to around 20 April. He then travelled to Naples, returning to Rome in mid-May and staying there until early June.11 He commissioned three major works: from Gibson (Mars and Venus), from Thorvaldsen (Venus with an Apple 1821; fig.3), and from Canova (The Sleeping Endymion 1819–22, Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth).

Gibson wrote a series of letters so that this important client was informed of progress but also to embed the idea of his complete dedication to this commission. The first of these communications, dated 4 December 1819, was composed at a time when Thorvaldsen had left Rome for an extended visit to Copenhagen, leaving his own commission from the 6th Duke in his studio to be worked on by assistants. In his letter Gibson carefully emphasised his own absolute, personal commitment to obtaining only the finest marble for the Mars and Cupid, which he knew was crucial to its beauty and success and at the same time might relate to the 6th Duke’s well-known passion for mineralogy:

After waiting three months I did reserve a block, from Count Monzoni at Carrara, but I am sorry to say that I was obliged to refuse it on account of stains, one of which I feared might appear on the head of Mars. & the other on the body of Cupid. I do not suffer any loss in rejecting this block of marble.

Another person at Carrara has kept me two months in expectations (who) after all has disappointed me. This very day I have intelligence of another that will fit my purpose.

In the course of two months a person is going to Carrara to purchase marble for Canova if I do not reserve mine in the meantime I [purpose] going with him. He is the son of Canova’s foreman. —-

I am sensible my lord, that this delay will disappoint you but your disappointment can not be more than my anxiety to begin this work.12

As well as showing that he was able to call upon the expertise of Canova’s workforce, Gibson also conveyed that he would be working only with the best equipment that had been chosen by the leading poetical sculptor in Britain, John Flaxman: ‘Mrs Johnstone here with Mr & Mrs Hall has sent me a present from England of a new set of tools to execute in her own terms “my favourite group of Mars & Cupid”. They were selected by the great and goodhearted Flaxman.’

Gibson also took care in the letter to confirm his continuing sociable acquaintance with the 6th Duke’s stepmother Duchess Elizabeth, who, with the Duke’s agent Gaspare Gabrielli, was the Duke’s main source of information about his commissions underway in Rome: ‘Yesterday I did pay my respects to her Grace who is quite well, and I was sorry to hear that some of the marbles which you have received from Rome are broken, if such things are packed as they do statues they cannot break but in the unpacking.’ Sadly his advice was not heeded, as the unpacking of Thorvaldsen’s ill-fated Venus with an Apple in December 1821 demonstrated.13 His courting of the Duchess Elizabeth paid dividends: in 1823 she wrote to Sir Thomas Lawrence that Gibson and Wyatt were the ‘best’ English sculptors in Rome.14 He was also equally careful to mention Canova’s approbation and support, knowing that the Duke idolised him and was eagerly awaiting his Endymion, his reference a masterstroke of empathy: ‘I always fancy that the last figure which Canova has done is the most perfect’. But after stressing perfection he inserts an unsettling reference to the Duke’s other commission, presenting Thorvaldsen’s Venus as a negative against his own positive action: ‘marble [of the Venus] is good. There are a few faint spots about the lips but nothing worth mentioning as soon as I do receive my marble I shall instantly work again’.15 This cleverly brings the Duke’s attention once more to Gibson’s own search for the best marble against the defects present in Thorvaldsen’s. Finally, at the bottom of the page he put a small but important note to show his continuing closeness to Canova: ‘My address is allo studio del Marchesi Canova a Roma’.

On 18 August 1821 Gibson wrote to inform the Duke that he had successfully purchased marble from Carrara and had notice of its imminent shipment to his studio.16 A month later, on 20 September, and giving his address as ‘Gibson scultore inglese Palazzo Poli, 2nd Piano, Roma’, he recounted the dramatic journey of this block of marble ‘from the ripe grande to my studio … drawn by twenty buffalos, the drivers had in their hands long poles like spears to prick the animals and also carried lighted torches followed by crowds of people’.17 Gibson would have been aware of the Duke’s love of the theatre and dramatic effect, and how it played in this narrative of his group’s evolution from inert marble block to living sculptural group. Of the careful shaping of the marble he wrote: ‘It is of the best quality and its external appearance is most favourable, in the course of a month or two I shall see it internally. My man began to work on it yesterday morning.’ Small alterations to the group that had been ‘so long under my eye’ were carefully reported, including changing the positioning of Mars’s legs, raising the head of Cupid ‘a little’ and introducing another form of helmet for Mars. Then once more he subtly implies the approval of his changes by Canova and another leading artist with whom the 6th Duke and Duchess Elizabeth were acquainted: ‘Canova was quite delighted with the alterations as well as [Vicenzo] Camuncini the Painter.’

Further letters kept the Duke updated on progress, relating the care and attention that the sculptor was personally lavishing upon this important commission and the continuing sanction of leading figures. From these it is known that by 10 October 1821 the marble was in the studio with his workmen working on it over a period of fifteen days, allowing Gibson to form an opinion of the marble’s purity: ‘it is most beautiful’.18 Yet on 9 November he breaks the news that although the marble ‘continues to be very fine’, and despite every precaution, ‘it will have some faint marks about the legs’.19 Finally, on 16 May 1826 he reports that he has completed the group and requests that the 6th Duke allows the work to be seen in London at Devonshire House, before being dispatched to the Sculpture Gallery at Chatsworth.20

Chatsworth and the 6th Duke’s collecting activities

Designed by Jeffry Wyatville, the extension to Chatsworth was being constructed when the 6th Duke was making his purchases from Roman sculptors’ studios in the 1820s. An early proposal by Richard Westmacott for the placement of these sculptures in the new Sculpture Gallery indicates the volume and quality of the work that was acquired. The dazzling display of white marble ‘poetical sculptures’ by Canova, Thorvaldsen, Bartolini, Tadolini, Gibson and others was set in an interior that made the most of natural and artificial light, achieving strong contrasts between the white and coloured marble artefacts in a simple natural stone interior.21 These elite white marble sculptures were carefully staged on pedestals of distinctive and rare coloured marble, with those pedestals of local stone decorated with panels of different coloured marbles, or inlaid ‘mosaic’ work executed at the nearby Ashford Marble mills. The Gallery also housed equally distinctive marble columns, vases and tazze, along with other, smaller decorative works, that the Duke acknowledged were a particular feature of the gallery. In January 1840 he was still busy with the installation – ‘Putting up the red cipollino’ as he records in his diary22 – and in February he visited mineralogist James Tennant’s shop where he admired a slab – ‘a beautiful thing’ – for which £50 was asked.23 In March he was ‘very busy [with] pavements & marbles’.24

But although the tempo of acquisition slowed after 1834, the 6th Duke’s enduring desire to continue this contemporary sculptural project persisted, despite the limited space for accommodating further large-scale works. One example of this impulse was his purchase of Gibson’s relief of Hero and Leander. He commissioned this in 1839, during one of his extended continental tours (this one including a visit to Sicily, Athens, Smyrna, Constantinople and Malta). The final marble was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1841 (no.1236) before being placed in the Sculpture Gallery at Chatsworth.25 By now Gibson was one of the Duke’s favoured sculptors – he mentions him in a diary entry of 1846 as ‘good old Gibson’ – as well as a trusted friend and a major point of contact in Rome. The acquisition of Gibson’s Hero and Leander seems to have been in the 6th Duke’s mind for some time – his earlier interest in the subject is indicated by his having a tapestry depicting it in his dressing room at Chatsworth in 1830.26 According to Gibson’s account in Lady Eastlake’s Life of John Gibson, he first saw a model for the relief in Gibson’s studio which the sculptor had been encouraged by Canova to make from a drawing, and the 6th Duke additionally told Gibson ‘that Canova had mentioned it to him’.27 At Chatsworth there is a pencil, ink and watercolour wash signed ‘f. Gibson’ and dated ‘Rome 1823’, a loose sheet on an old mount that relates closely to a plaster relief now in the Royal Academy collection.28 Presumably the drawing is that described by the 6th Duke in his Handbook to Chatsworth and Hardwick composed in 1844, which reads as follows: ‘in our early acquaintance he [Gibson] made a sketch of it in a small album: “In that dear embrace | soul rushed forth to soul”’. Here the 6th Duke is quoting from the 1840 poem ‘The Meeting of Hero and Leander’ by Margaret Sandbach, a friend of Gibson.29

Displaying Hero and Leander

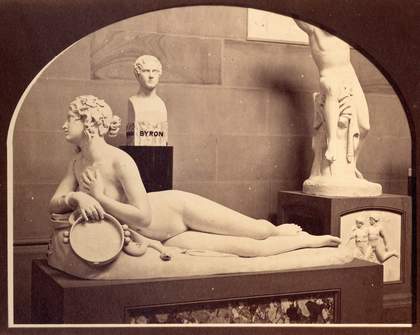

Fig.4

Photograph showing the arrangement of works in the north bay of the west wall of the Sculpture Gallery, Chatsworth House, 1858

© Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees

During the 1850s the 6th Duke placed Thorvaldsen’s marble Portrait Bust of Lord Byron 1817 next to Hero and Leander. A photograph taken at the time of the Duke’s death in 1858 shows the arrangement of works in the north bay of the west wall of the Sculpture Gallery (fig.4); the Portrait Bust of Lord Byron appears to the left of Gibson’s Hero and Leander, the lower left corner of which is just visible in the top right corner of the photograph.30 Lord Byron was of course a troubling reminder of the 6th Duke’s cousin, Lady Caroline Lamb, and her dysfunctional relationship with the poet. But these works also relate to other friendships. Thorvaldsen had modelled the bust of Byron from life in April–May 1817 and the Chatsworth work is one of four known versions of this herm-type bust (a portrait in which the shoulders and torso are truncated into a square-sided shape or pillar). It was originally the property of the Revd Francis Hodgson, a friend of both Byron and the 6th Duke. According to a family memoir it was given to Hodgson by a pupil when he was provost of Eton (1840–52). Hodgson was a friend of the 6th Duke, and on Hodgson’s second marriage to Elizabeth, second daughter of Lord Denman (another mutual Cambridge friend), the Duke presented him with the living at the parish of Edensor on the Chatsworth estate. Hodgson died in 1852, when the bust seems to have become the 6th Duke’s possession.

Placed on a pink-veined marble base with letters cut from the Duke’s red limestone, the Portrait Bust of Lord Byron bears the names of Byron, Hodgson and Thorvaldsen. This work serves as a reminder of the 6th Duke’s first tantalising ‘glimpse of Italy’ in 1817, when John Cam Hobhouse, another mutual friend to him and Hodgson, showed the Duke Byron’s manuscript of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto IV having just been completed. Memories of Italy, of friends past and a strong sense of life’s transience, are found in both Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and in the arrangement of the Sculpture Gallery. In this context the placement of Hero and Leander in conjunction with the bust of Byron can also be seen to allude to the poet swimming the Hellespont, as found in Byron’s Don Juan, Canto II:

A better Swimmer you could scarce see Ever,

He could, perhaps, have passed the Hellespont,

As Once (a feat on which ourselves we prided)

Leander, Mr. Ekenhead, and I did.31

The Duke and Gibson’s mutual desire to show Hero and Leander to greatest advantage included the sculptor making his long-awaited visit to Chatsworth in 1844 to select a site on the north bay of the west wall. This is clear in a letter to the 6th Duke that Gibson sent from Rome on 23 May 1842:

Two years must still elaps [sic] before I can avail myself of your kind invitation to Chatsworth because of the volume of work going through the Rome studio. I was informed when the Hero & Leander was in the exhibition it was placed in the worst light. When in your gallery it should be so placed that the figures should cast some shade upon the ground of the basso relievo – a light from the side not a front light.32

In the Sculpture Gallery the light comes from the lantern above and also from the side when the door through to the Orangery is open.

London versus Rome: Remain or leave?

During these years between the first of Gibson’s commissions from the 6th Duke and his completion of Hero and Leander, Rome continued to be the prime location for the making and consumption of contemporary sculpture. It was a centre where Anglo-Italian sculptural exchange was not simply operating between two nations, or nation states, but within a shifting, internationally configured art market, where the movement of goods and people within the sculpture trade was always, to some degree, transient rather than fixed.33 Furthermore, while the notion of artistic exchange was always central to the sculpture trade, there were other commercial and economic factors that were equally important to successful outcomes. As already indicated, not all sculptors who travelled to Rome, demonstrating a ‘concentration for fame’, were able to navigate their way through this complex environment, one that was at the same time subject to unexpected and devastating events.34 Notable among these were the cholera epidemics of 1835–8 that threatened health and livelihoods indiscriminately.35

In Britain the young Queen Victoria’s unexpected accession to the throne in June 1837 was seen by the Manchester Guardian as ‘a circumstance full of hope and promise’ with the prospect of ‘the commencement of a new era’.36 For some British sculptors resident or studying in Rome, this created a strong pull to return home, just as the threat of the cholera epidemic was making them look to their immediate physical safety. For many a crucial decision had to be taken: whether to remain in the pivotal international sculpture market of Rome or to return to the more insular artistic environment of Britain, where new opportunities beckoned. Among these was the Royal Academy’s move in 1837 from Somerset House to the east wing of the recently completed National Gallery on the newly designated Trafalgar Square. Inaugurating the new monarchy evoked a widespread civic and national engagement with national identity and patriotism that advanced the demand for public and national sculpture. The most significant national monument would be raised on the Royal Academy’s then doorstep – the Nelson ‘Testimonial’ destined as a nodal point in the newly designated Trafalgar Square, the result of an open competition held in 1838.

Commercial opportunities for sculptors at home also seemed to be expanding with the founding of the Art Union of London in 1837, which would soon offer prizes for sculpture and commission medals among its works. During this year rumours were also circulating about the attempts within the Royal Academy, promoted by J.M.W. Turner and Chantrey, to exclude non-resident British artists from being eligible for election as Associate or full Academicians.37 In this regard it may not have been coincidental that Gibson, with the support of Charles Eastlake, had been elected Associate of the Royal Academy in 1833 and Royal Academician in February 1836 – another indicator of the reputation and influence of this resident of Rome and evidence of his institutional standing in Britain. Gibson’s attainment could be seen to pose a threat to Chantrey, whose professional success had been established by operating under the flag of an innate ‘Britishness’ that promoted home-grown art uncorrupted by foreign influence. Following the death in May 1850 of Richard James Wyatt, Gibson’s closest sculptor friend and neighbour in Rome, Gibson recalled that Chantrey had led the opposition to Wyatt’s election to the Academy: ‘Sir F. Chantrey said on the occasion, in defence of his exclusion of Mr. Wyatt, that the existing law of the Academy, which prescribed that the candidate should be resident in England, must be adhered to strictly. In my case it would appear that this rule had either been neglected or waived, owing to Sir C. Eastlake’s intervention.’38

Rome: Opportunities and threats

Elsewhere in Gibson’s correspondence there is evidence of his absolute conviction that the working environment and artistic networks in Rome provided unparalleled opportunities for British sculptors that were lacking at home: ‘Every young sculptor in England bungles his way as he can’, he wrote in March 1857; ‘nor do they visit, generally speaking, each other’s studios, which at Rome is universal practice, and more, they point out errors while their models are still in clay’.39 In 1836 he had commented to Edward Bulwer Lytton on this established tradition of artistic interchange: ‘some of the artists of different nations here visit each other’s studio – consult with one another there on what they do. I never model a work without consulting Thorvaldsen and others and have always found great benefit from this practice – it is combining together to advance art – where art is a mere trade this is not the practice.’40 It was also, of course, a good way to keep an eye on the competition.

While the notion of artistic exchange was always central to the sculpture trade, there were other commercial and economic factors, as well as social networks, that were equally important to successful outcomes for British sculptors working in Rome in the 1830s. As already noted, this crucial time of change and uncertainty at home and abroad affected decisions as to whether sculptors should remain in or leave this international sculpture centre. Gibson, of course, decided to remain. For him – as the extract from the previously cited letter to Crouchley indicates – Rome was his professional centre, and we could inflect that statement to read that for him there was ‘no place like Rome’. He continued to be an enthusiastic advocate of it as ‘the best School in Europe’, as he described it on arrival in 1817, and later he came to call it ‘the University of Art’.41 Part of this conviction is contained by his role as a protagonist for the unrealised project to create an English Academy of Fine Art there. Although this project failed to gain traction, he continued this advocacy of the city as a training ground for young sculptors who sought his help, encouraging those who in the 1830s were finding the going tough not to give up. Gibson’s kindness and support for young sculptors arriving in Rome is well known, and was part of his ambition to raise the quality of contemporary sculpture. Yet it was perhaps not entirely altruistic as it also allowed him to keep his Roman network firmly under control and to promote British art within an international field of practice which he would lead.

Among those open to the training that Gibson advocated was William Calder Marshall, who resided in Rome from 1835 to 1837. In his letters to his father, written between 18 and 26 May 1837 – that is, before the re-emergence of cholera that August – Calder Marshall reported that he was ‘urged to stay’ by Gibson and Richard Wyatt, as well as a ‘shoal of small fry’.42 Despite this, he remained resolute in wanting to return to England, seeing Rome as crucial to his training but not his final destiny. Resisting Gibson’s encouragement to remain he decided in favour of support from Chantrey, who would help him to locate a London studio on his return. In a letter dated 25 May 1837 he details the economic realities of practising sculpture which made life difficult: marble, he writes, is ‘expensive even in Rome’, echoing the experience of John Hogan, who in 1824 had also commented upon the expense not of the marble itself but of the cost of it being transported to his studio. Calder Marshall had by this date found a new studio nearer the fashionable part of the city sublet by Joseph Gott, an example of this widespread practice of using the cheapest accommodation available to greatest advantage. He also writes of his wish to begin a grand class of subject, The Creation of Adam When He First Sees the Light, and of the cheapness of ‘antiquities of all sorts’ that allowed him to buy ‘several small objects from Herculaneum’.43

The cholera pandemic that occurred in 1836 and again in the late summer of 1837 is described by Sue Brown in her biography of the painter Joseph Severn as ‘an apocalyptic moment in British engagement with Rome’ that prompted many sculptors to leave for good.44 A two-week quarantine imposed on travellers to and from Rome as well as the dangers of contagion stopped the vital flow of visitors and trade upon which sculptors depended. A major departure was that of the ‘Prince of Sculptors’, as Gibson and others referred to Thorvaldsen, who decided to leave Rome after one of his models became ill, and the wider negative impact that the disease had upon his business. Leaving for Copenhagen on 13 August 1838 and taking with him the entire contents of his studio, he left a gap that established sculptors such as Gibson and Wyatt were eager to fill. But while Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and the French artists in Rome hunkered down in the Villa Medici in self-imposed quarantine, the British sculptors had no such locus, having failed to establish a dedicated building for the ‘English Academy of the Fine Arts’, and were therefore dispersed across the city.45 Among those directly affected by cholera were Gott, who lost his two children and much of his business, and the little-known sculptor Henry Behnes Burlowe, who rented Severn’s coach house but died in September 1837 at the age of thirty-five, having caught the disease from others whom he had unselfishly nursed.46 A single page of the Art-Union published in December 1840 captured the hopes and disappointments sculptors faced in Rome and London in the late 1830s: an account of Behnes Burlowe’s life and death was set alongside an account of the by then precarious state of the Nelson Testimonial competition, and rumours of plans for a ‘National Mausoleum’.47

Not all British sculptors working in Rome before cholera struck found it possible or wished to maintain the high profile and easy sociability that Gibson achieved, with some deliberately keeping their distance from their compatriot sculptors, maintaining the ‘bungling’ isolationism that Gibson decried. After arriving in Rome in 1827, where he stayed for two years, Musgrave Lewthwaite Watson deliberately ‘hid’ himself, wanting to practise sculpture and at the same time immerse himself in the acquisition of the Italian, French and German languages. He preferred working with French and German sculptors as he felt they ‘lived more cheaply, and got more for their money, than English artists, and economy suited his finances’.48 He was successful to the extent that worried relatives tried to locate him in Rome through David Dunbar, one of Chantrey’s former assistants, such was his assimilation into the German coterie of which he was thought to be a native.49 Another of these sculptor ‘hermits’, whom Gibson noted ‘had his own peculiar notions on this subject’ and kept himself deliberately ‘aloof’ or apart from his fellow sculptors, was John Graham Lough, who arrived with his family in Rome in 1834 and stayed for three years. Trying to escape the cholera epidemic, he moved briefly to Naples before returning home to England. According to Gibson:

Lough was in Rome for a year or so working with great rapidity without having seen a single studio nor will he allow any artist to enter his place so that he goes on entirely alone. A gentleman here to whom he had brought a letter of introduction to, told me that he offered to make him known to Thorvaldsen, thinking that Mr L. might wish to consult the first sculptor of the age on his profession. Lough said, No Sir I never invited [strangers] to my studio –50

This separateness seems to have worked to his advantage, as on his return to England Lough was initially successful in his proposal for the Nelson Testimonial, in that he was commissioned to make the lions for this hybrid monument, although these were never put in place. Both Chantrey and Gibson had wisely stayed aloof from this public sculptural melee, while Gott and Calder Marshall were among the many with lesser reputations who faced the vagaries of this very public competition in the hope of victory.

Art historian Roberto Ferrari has revealed that Gibson always took great care to present himself as an artist/designer as opposed to a direct participant in the ‘money making trade’, as Gibson indicates in his letter to Crouchley cited at the beginning of this paper and in his communications with his patrons such as the 6th Duke.51 But his seeking after perfection came at a price, as noted and accepted by the 6th Duke in his diary entry for 16 January 1839: ‘Bezzi’s modest price for amorini, 65 luigi, whereas Gibson had charged 180£! I have ordered Hero and Leander of Gibson’s’.52 Many like the Duke were willing to pay for Gibson’s internationally recognised art, and his reputation, despite Chantrey’s machinations, continued to flourish at home. The sculptor’s handling of his business under the guise of an artist that operated outside the mundane realities of commercial activity is nowhere more clearly articulated than in his cleverly constructed and subtle correspondence, where he is seen adapting adroitly to the needs of friends such as Crouchley, and those of important patrons like the 6th Duke, manipulating his client base in Britain to his advantage from his beloved Rome. But above all his success lay in his empathetic engagement with all those with whom he made contact: whether young sculptors embarking on their careers in Rome, friends of long standing or those who came into his circuit later, such as Margaret and Henry Robertson Sandbach, or influential institutional figureheads like Eastlake – an empathy evidenced in the timbre of his correspondence. Like Chantrey he would leave an important and lasting bequest to the Royal Academy, but one that, despite the challenges that it presented, was acquired from an enduring and open engagement with Rome, the international heart that generated and sustained his art.