Rome shall be my battlefield where I shall be surrounded by more powerful antagonists than are to be found in England – there my life would be spent in making busts and statues of great men in anti-sculptural dress. Here I am with many others employed upon poetical subjects – those that demand the highest efforts of the imagination and the greatest knowledge of the beautiful.1

The sculptor John Gibson (1790–1866) is best known for his mythological figures in marble, with subjects ranging from Hylas Surprised by the Naiades 1827–?36, exhibited 1837 (Tate N01746), to the Tinted Venus 1851–6 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool), the latter frequently cited and written about as the exemplar of his interest in the revival of polychrome sculpture in the nineteenth century.2 Gibson’s interest in ‘poetic subjects’, inspired by works from ancient Greece and Rome in form, history and subject, dominated his oeuvre and were the works of which he was most proud. As the quotation above shows, Gibson went to Rome and chose to remain there because he believed it was only there, among an international community of painters and sculptors and close geographically to the foundation of classicism, that he could flourish as a sculptor, making poetic subjects of his choice. He knew he could have earned more money living and working as a sculptor in London, but to do so he believed he would have been forced to spend his time exclusively engaged in portrait statues and busts of his contemporaries in modern dress, a practice that famously repulsed him: ‘The human figure concealed under a frock-coat and trousers is not a fit subject for sculpture, and I would rather avoid contemplating such objects’.3

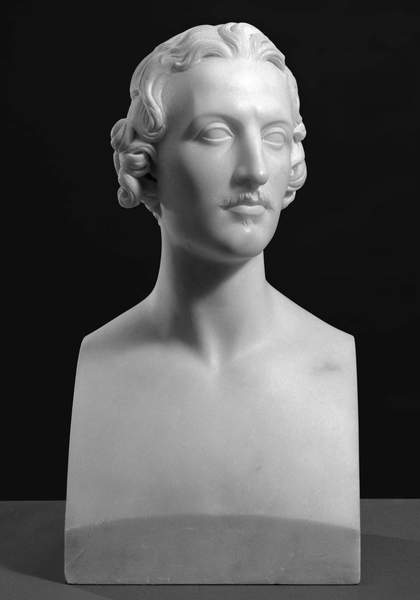

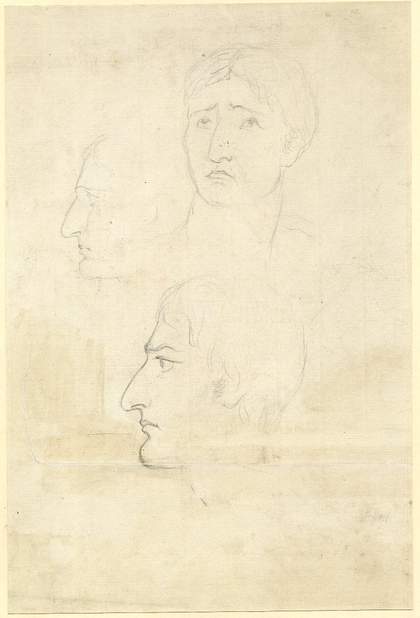

Fig.1

John Gibson

Bust of William Bewick 1827–53

Tate T06866

Nevertheless, over the course of his career Gibson did in fact model a remarkable number of portraits in various forms, comprising approximately one-third of his sculptural oeuvre. This body of portraiture work included more than forty-five busts, including Tate’s Bust of William Bewick 1827–53 (fig.1), ten medallions, eight statues and thirty-five funerary monuments depicting reliefs of the deceased.4 This is a significant collection of work for a sculptor who notoriously claimed to eschew portraiture. Perhaps even more surprising is the number of portraits Gibson showed at major venues during his lifetime. Of the thirty-four works he exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) in London, fourteen were portrait busts, statues or monuments.5 His first exhibited RA works, shown in 1816 – Bust of a Young Lady (no.914) and Bust of H. Park, Esq. (no.924) – and his last exhibited RA work, shown in 1864 – H.R.H. the Princess of Wales (no.869) – were notably all portrait busts. And although the International Exhibition of 1862 in London is where Gibson famously exhibited his Tinted Venus and two other polychrome statues, busts of the Italian model Grazia (lent by Queen Victoria) and the 2nd Duchess of Wellington (lent by the sitter) were on display elsewhere in the grand hall. Lady Elizabeth Eastlake declared his portraits to be ‘very remarkable’ for their ‘look of monumental grandeur’, and Gibson himself argued that in portraiture it was important to maintain the example of the Greeks and Old Masters, showing ‘men thinking, and women tranquil … like a superior class of beings … serious and calm’.6 The latter phrase in particular is interesting, as it alludes to the aesthetics of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, which will be discussed later in this essay. These ideas, combined with his exhibition history and the number of works in his oeuvre, seem to contradict Gibson’s denial of portraiture as a significant part of his artistry.

This essay, then, is the first to discuss at length Gibson’s portraiture practice and will explore his artistic motivations and strategies, his interactions with sitters and his portraiture practice in comparison to some of his contemporaries in London and Rome.7 For although Gibson held up portraiture as an important art form, he was unfortunate to have begun his career just as that of Sir Francis Chantrey (1781–1841) was entering a period of unprecedented domination of the domestic market for portraits. Gibson’s frequently stated personal dislike of Chantrey (whom he described as ‘a man of no genius’), and his efforts to distance his practice from that of his most commercially successful fellow countryman, also illustrates an important division of the London art market and its aesthetic.8 The essay will also focus on a small number of under-researched portraits in Gibson’s oeuvre, such as his aforementioned bust of the painter William Bewick, an undocumented bust of a man at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and his portrait statues of the Hon. Mrs Murray 1842–6 (Stanford Hall, Leicestershire) and Queen Victoria 1844–7 (Royal Collection, London).

Patrons and friends: The early busts

It is well established in art history that painters and sculptors from the Renaissance to the present day have frequently relied on portraiture as a means of earning an income. Only a few artists, such as Joshua Reynolds and Francis Chantrey, excelled as masters in this field. Thus, Gibson was no exception to the rule, and certainly one finds a preponderance of portrait busts especially in his early career, as he sought to establish himself as a financially independent sculptor.

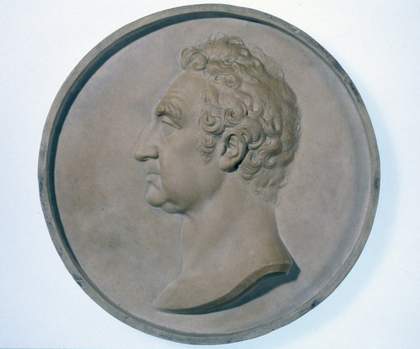

Fig.2

John Gibson

Medallion of William Roscoe 1813

British Museum, London

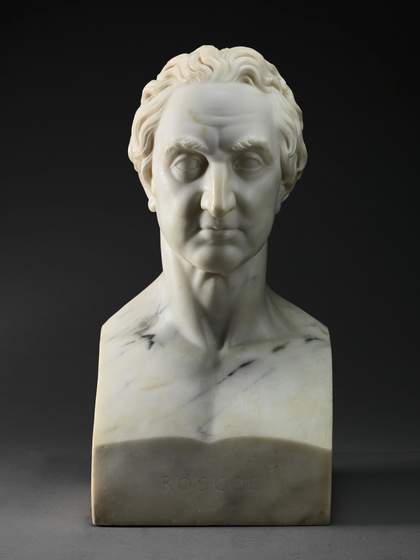

Fig.3

John Gibson

Bust of William Roscoe 1819

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

Among the important portraits that Gibson made in these early days were two he modelled of William Roscoe, a retired lawyer who became an avid art collector and biographer of Renaissance men such as Lorenzo de’ Medici. Roscoe first met Gibson when he was working as an apprentice at the Franceys’ marble works factory on Brownlow Hill in Liverpool. He commissioned from Gibson a decorative mantelpiece and effectively became the sculptor’s first official patron. Roscoe encouraged Gibson to visit his home, Allerton Hall, where he could study Roscoe’s prints and drawings collections and thus enhance his understanding of art. Roscoe was an active supporter of the arts in Liverpool, establishing with Henry Blundell the Liverpool Academy of Arts. Indebted to Roscoe for his patronage and friendship, Gibson made a terracotta portrait medallion of him (fig.2) that he exhibited in the 1813 Liverpool Academy (no.310). This medallion may have been inspired by quattrocento painting precedents, of which Roscoe would have been fond as an enthusiastic collector of Renaissance art. The sitter’s friend Thomas Stewart Traill later wrote of this medallion ‘There are several representations of [Roscoe]; but none of them appear to me so finely to express the characteristic traits of his head as John Gibson’s medallion … The Terra Cotta medallion is Mr Roscoe, as I should wish to remember him’.9 Gibson also made a portrait bust of Roscoe in the form of a herm – a portrait that truncates into the shape of a square-sided pillar – that he modelled from life in late 1816 and subsequently carved in marble in Rome in 1819 (fig.3).10

Fig.4

John Gibson

Portrait Bust of George W. Watson Taylor 1818–19

Osuna Art and Antiques, Kensington, Maryland

Before Gibson headed to Rome in 1817, he spent as much as one year or more in London, where evidence shows he worked in the studio of Joseph Nollekens, then the longest-established portraitist in Britain. He met a number of individuals in the capital city who proved helpful to his burgeoning career.11 One of these men was George Watson Taylor MP, whom he met through James Christie, the son of the founder of Christie’s auction house. Gibson dubbed Watson Taylor ‘one of the most liberal patrons of art’; he commissioned portrait busts from Gibson of himself, his wife and four children, including a baby that Gibson described as ‘a little thing with no shape at all’.12 In a letter to Roscoe from the late summer of 1816, Gibson wrote that he was modelling the busts of Mr and Mrs Watson Taylor, having accompanied them on a visit to Lord Spencer’s villa on the Isle of Wight.13 Watson Taylor was pleased with Gibson’s model of him (fig.4), even more so (according to Gibson) than a version recently done by Chantrey.14 The bust of Watson Taylor rests on a socle – a low supporting plinth – as does that of his wife and each of the extant children. With drapery wrapped around his shoulders and his gaze looking towards his right, the bust gives Watson Taylor a sense of dignity deserving of a Roman senator and arguably reflects Gibson’s immediate exposure to Roman busts that he would have seen in the Capitoline and Vatican museums while he completed it. Gibson finished the children’s busts in marble while in London, exhibiting those of the two elder sons at the 1817 RA exhibition.15 Those of the husband and wife he completed in Rome in 1819, exhibiting the bust of Mrs Watson Taylor at the RA that year.16

Gibson’s relocation to Rome at this time coincided with a transition in the London portraiture market, in which Nollekens, the leading portraitist, seems to have increasingly recommended the younger sculptor Chantrey as ‘the man for a bust’.17 Chantrey’s naturalism, which won him admirers from 1811, began to translate into a formidable commercial practice in busts, statues and public monuments.18 Chantrey’s increasing use of modern technology, notably his new pointing instrument, streamlined his practice from 1816, at the moment of Gibson’s arrival in London.19 Between 1811 and 1820 Chantrey received commissions for over eighty portrait busts, more than Gibson produced in his entire career. He was also developing a carefully crafted sculptural nationalism, forged in tendentious opposition to Canovian neoclassicism.20 It was perhaps not surprising that Gibson, who, by inclination, would become more of a Roman sculptor, decided to distance himself from the British portraiture craze, a marketplace in which he could not hope to compete.

In the 1820s, as Gibson’s reputation for mythological works began to take hold, he nevertheless continued on a small scale to produce portraiture. There were not very many patrons who approached him for portraits at this time, but undoubtedly this was because he was still new in Rome and attempting to balance his interest in designing mythological works with making portraits to earn a living. Some of the portraits from this period include the 1822 busts of C. [Cuthbert] Ellison, M.P., exhibited at the RA in 1822 (untraced) and Charles, 1st Baron Colchester (Westminster School, London), possibly exhibited at the RA in 1823 as Bust of a Nobleman; the 1823–8 bust of Walter Savage Landor (National Portrait Gallery, London); the c.1829 bust of Mrs Harriet Cheney (untraced); and a bust of Miss Brotherton from the late 1820s (untraced). Tate’s bust of William Bewick was modelled in 1827, at a time when Gibson was also working on his Hylas Surprised by the Naiades. While some of the busts made at this time reflect commissions, this one illustrates a pattern in Gibson’s career in which he modelled busts of close friends, or people whose look caught his attention, on a non-commercial basis. It also shows him grappling with the question of how to realise pure classical form, alongside the expression of the particular appearance and character of the sitter.

The bust of Bewick was modelled at Gibson’s studio in the Via Fontanella in Rome in the summer of 1827. Bewick, a history painter from Darlington in the North East of England, was in Rome to copy sections of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, a job he had been employed to undertake by the painter Sir Thomas Lawrence, who hoped to have copies for the use of the RA in London. Bewick left England in the spring of 1826 and undertook a gruelling six-week sea journey to Genoa. He visited Pisa and Florence before arriving in Rome in September. He remained there throughout 1827, working on his copies and enjoying the company of British artists, including the painters David Wilkie and Joseph Severn and the sculptor James Wyatt.21 In a letter of 2 June 1827 he recorded that he had sat for a bust by:

the first English sculptor here … his name is Gibson, a fine, simple-minded, clever genius, with a very refined and poetical taste, and devoted to his art. He tells me all that he lives for is to leave some fine works for posterity. He is very attentive to me, and we walk almost every evening, talking of art, and the fine antique statues.22

Bewick later recalled that the bust was modelled ‘not at all by my desire’ but that ‘Gibson, in the first place, asked me to sit to him’.23 There is no reason to doubt this account, as the bust was not immediately carved in marble but remained in Gibson’s studio in plaster for another twenty years before Bewick requested a marble version in 1847. Indeed, Gibson and Bewick appear to have developed a good friendship in Rome, to which the bust attests, and Bewick always spoke warmly of the sculptor in subsequent accounts of his time in Rome. The two men certainly shared a commitment to an aesthetic of classical purity.

Like his bust of Roscoe, Gibson’s bust of Bewick is in the form of a herm, its torso taking on a square shape. In ancient Greece and Rome such busts were usually of deities and mounted on pillars that marked boundaries, but in eighteenth-century Rome the form was revived for bust portraiture, and enthusiastically adopted by generations of neoclassical sculptors. As will be shown in this article, later in his career Gibson even modified the herm format for busts of women, giving them the features of breasts to emphasise their femininity. Gibson’s bust of Bewick portrays a strikingly handsome young man, with thick curls, a wispy moustache and a patch of hair below the mouth. He is turned to his left, head slightly tilted. A hint of a furrowing between the eyes suggests concentration, giving the portrait an intellectual, perhaps even romantic air. The smooth, highly polished and translucent marble is employed to suggest smooth flesh (and plenty of it, in the absence of any drapery). The bust achieves a degree of immediacy, and intimates the artistic character and energy of the sitter, but at the same time Gibson stays true to the classical form of the bust – the eyes are unincised, generalising the gaze of the figure, and the eyelids are formalised. The portrait searches, in other words, for the ideal combination of classical form with the suggestion of a real, contemporary body.

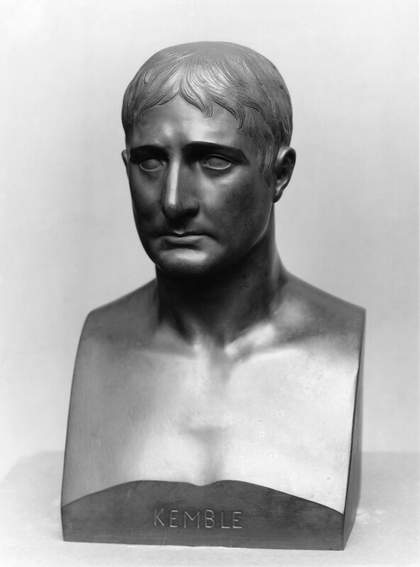

Fig.5

John Gibson

Bust of John Philip Kemble 1814

National Portrait Gallery, London

Gibson’s portrait shows many of the obsessions of his work, observing nature while innovating within classical forms. Famously, he later recalled that many of his neoclassical subjects had their origins in the observation of chance gestures; for instance, the Wounded Amazon 1840 (National Museum of Wales, Cardiff), who lifts her tunic to observe her wounded thigh, was based on the characteristic gesture of modern Roman women stopping suddenly and turning to view their heels in the streets.24 The frequent argument made by Gibson was that he did not merely produce stale homages to classical statuary, as his critics charged, but emulated the Greek spirit by observing nature while staying true to the purity of Greek design, and giving antiquity its due respect.

Fig.6

John Gibson

Bust of John Philip Kemble 1814

Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

Fig.7

John Gibson

Studies for a Portrait of John Phillip Kemble 1814

British Museum, London

Along with Bewick’s bust, Gibson utilised the herm form for many other portrait busts of men. These include notably his earliest bust, that of the actor John Philip Kemble from 1814 (fig.5), which he made in bronze when still in Liverpool. Echoing Roman imperial portraiture, as well as the famous bust of Napoleon by Antoine-Denis Chaudet of 1807–9 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London), the Kemble is sternly classical with unincised eyes, low relief stylised hair, naked chest and a flat section at the front of the bust where the name of the sitter is inscribed. This bronze herm-style bust, however, differs greatly from its plaster cast (fig.6). Like most sculptors of his day, Gibson would have created a clay or wax bozzetto or model of his sitter, and from this a plaster cast would have been made. In the case of Kemble, the plaster cast, showing Kemble in his famous role as Cato from Joseph Addison’s eponymous play, turns out to be remarkably different from the more famous bronze reduction made afterwards. Extant drawings also show that Gibson made a number of sketches on paper of his sitter in costume in preparation for this work (fig.7). Gibson documented that while Kemble posed for him, the actor ‘had a looking-glass in his hand, and, frequently examining his face, corrected me’, which suggests that these sketches were made to assist him in capturing the right profile in the clay model.25 The plaster cast depicts Kemble in costume and shows the bust on a socle, thus reinforcing his appearance as an ancient Roman senator. Gibson likely exhibited this plaster version at the Liverpool Academy in 1814 (no.292), and bronze reductions of the bust, measuring just over one foot in height, were issued afterwards, reportedly given away by Kemble and sold by Gibson in his studio. These bronzes, in the form of a herm and showing Kemble with a bare chest, suggest an intentional simplification of the portrait for mass distribution.26

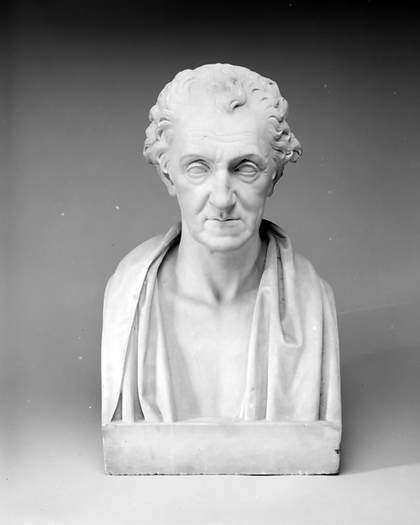

Fig.8

John Gibson

Bust of a Gentleman c.1830–40

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Other examples of Gibson’s use of the herm form for busts of men include the portraits of his aforementioned mentor William Roscoe (fig.3), the poet Walter Savage Landor, and his friend the artist Sir Charles Eastlake (see Sir Charles Locke Eastlake c.1840, National Portrait Gallery, London). In the case of the bust of 1st Viscount Cardwell from the 1820s, Gibson wrapped drapery around the herm as if to hide its rectangular shape.27 In another, even more unusual instance, Gibson enhanced the herm by adding classical drapery around the figure’s neck and shoulders, but still revealed the chest in front. This can be seen in a work in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art that heretofore has not been documented. Acquired by the museum in 1999, the bust of an unknown man of c.1830–40 (fig.8) is inscribed on the left side ‘I. GIBSON. FECIT’, which is one of Gibson’s known signatures, but it is not dated by the artist. The facial features in this bust are remarkably naturalistic, the sitter seemingly an older man with a wrinkled brow and furrowed, fleshy cheeks. His hair is ornately stylised, with one curl reaching down onto the top of his high forehead. Provenance for this work is scant and thus there has been little to go on to help identify the figure.

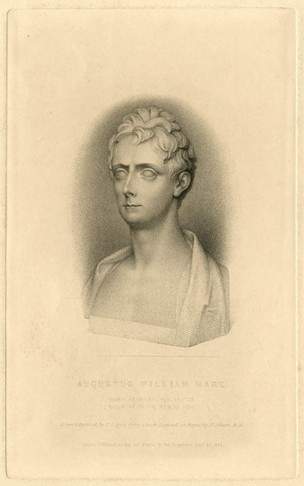

Fig.9

John Samuel Agar, after John Gibson

Augustus William Hare 1836

British Museum, London

However, a contemporaneous print (fig.9) may help identify him as Augustus William Hare (1792–1834), a minister who was born in Rome, raised in England, and who died in Rome and was buried in the Non-Catholic Cemetery there. As an author, he wrote a history of Germany and religious tracts, but his most famous work, Guesses at Truth (1827), was a collection of essays he co-authored with his brother Julius Charles Hare. Augustus Hare and his wife undoubtedly knew Gibson in the expatriate English community of Rome, and his widow may have commissioned the bust from the sculptor as a personal memento to bring back to England. The stipple engraving, dated 30 December 1836, was made by John Samuel Agar and is inscribed ‘from the Bust Executed in Rome by J. Gibson, R.A.’. The figure shows the same herm form and the subject wears drapery wrapped around his shoulders, albeit in a more pure, linear manner.28 No other extant male bust by Gibson has been identified with drapery wrapped around the neck and shoulders of the herm in this way. The stylisation of the hair and the single curl on the top of the forehead are also similar in both works. Assuming the print and the bust are of the same man, in the print Agar has clearly idealised him, removing all the traces of age and illness that Gibson captured more realistically for someone he likely knew personally and who died from consumption, even if only just over forty years of age. This bust is not documented in Gibson’s extant account books, so this work could be another example of a friendship bust, like that of Bewick, and thus was not recorded by the artist.

‘Bust making’: Gibson’s account books

In 1854 Gibson wrote a letter to his Liverpool colleague J.B. Crouchley, a sculptor, berating him for not working harder and always begging for money. Noting in particular Crouchley’s laziness as an artist, Gibson wrote: ‘You told me that you did not like modelling bust[s] – I never liked bust making but made many for the sake of money’.29 This seems to be an extraordinary statement coming from Gibson, who professed in his memoirs and throughout his life that he never was interested in fortune but sought fame, which he believed he could attain only by working in Rome.30 The fact is, though, that Gibson did earn some money making busts, as is evident in his extant account books.

These account books provide scholars with some evidence of the activities of Gibson’s workshop. Although incomplete in relation to his entire oeuvre and not well organised, they give some indication of his practice and the profitability (or otherwise) of his portraits. Gibson classified bust-making into two forms: portrait busts and fancy busts. Sales of the latter were lucrative for his studio, as they referred to either derivative figures from his mythological statues, such as Paris 1819–24 (Perth Museum and Art Gallery, Perth, Scotland), or mythological busts themselves, such as Helen of Troy c.1825–30 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London). In one of his account books, now held in the RA archive, he recorded that as of 1835 he had earned £640 for fancy busts, and as of 1836 he had earned £1,255 for fancy and portrait busts together, suggesting that each made up approximately half the revenue he earned for bust-making up to that date.31 Elsewhere on that same page (i.e. as of 1835–6), Gibson gave a summary list of ten busts that he had produced, including those of Roscoe and Lord Colchester, in which he had given a standard price of £50 each. In other cases he recorded a sum of £30, as in the case of Landor, which might suggest a friend’s rate.

By 1847 this price had risen, although friends’ rates were still applied. William Bewick, now living in Haughton-le-Skerne, near Darlington, ordered a copy of the bust that Gibson modelled of him in 1827 in marble. According to Bewick’s own account, some friends of his wife saw the bust in Gibson’s studio and brought home a drawing of it. Mrs Bewick was persuaded to seek a copy in marble. That year William Bewick wrote a letter to Gibson (the location of which is unknown), to which the sculptor wrote the following reply that well illustrates Gibson’s practice at that time:

Rome, March 1st, 1847

… The cast of your bust has been preserved. If you wish to have it I can send it to you – executed in marble it will cost you £20; for such a bust I charge £70. I think my agent in London, Mr McCracken, Old Jewry, will charge you five pounds for case, packing and carriage from Rome to London. So your bust, to which I should give myself some finishing touches, would cost you twenty-five pounds put down in London.32

Gibson seems not to be overstating the £70 price of his undiscounted bust, as his account books for 1843 document commissioned busts of Mrs Hogg and Mrs Hayter (both untraced) at £70 each.33 With the Bewick bust, the large discount of £50 on Gibson’s ordinary price is evidence of the friendship between the sculptor and the sitter, and it seems very likely he made little or no profit on the bust.34 But even with his general increase of £50 to £70 by the early 1840s, it is striking that Gibson still requested low prices for portrait busts – substantially cheaper than a bust by a leading London sculptor produced at the same time. Chantrey’s standard price in the 1830s was £210, but even a less esteemed sculptor, Henry Weekes, could command prices of £115 per bust.35 Even with the packing costs, shipping costs and duties, it must have been temptingly cheap for visitors to Rome to buy a bust when visiting Italy, rather than paying fuller costs when back in London.

Remarkably, however, from about the mid-1850s Gibson more than doubled his rates again, to £150 for a portrait bust. Gibson’s account books record that his busts of the 2nd Duchess of Wellington and Edith Mozley were both priced at £150; furthermore, the first marble bust of Princess Alexandra was £150, and two additional copies in marble were documented at £120 each, costing the royal family a total of £390.36 While this inflated price clearly represented his rise in international status, he may have intentionally raised his price to discourage people from commissioning busts from him. Conversely, he may have raised his rates specifically to help fund his estate plan to bequeath his artwork and a significant amount of money to the RA for the creation of the Gibson Gallery.37 That said, these rates still only put him on a par with British-based sculptors such as Patrick Park, and were still much lower than Chantrey’s a decade previously.

There were, of course, a number of reasons for the relatively low prices of Gibson’s busts. Not least among these was the access that Rome-based sculptors had to cheaper skilled assistants and to Carrara marble, which cut out the costs borne by London sculptors of dealing with the London marble merchants, whose cut added considerably to their overheads. Gibson proudly records in a note for the untraced portrait of Mrs Hayter, for which he charged £70, that even after the costs of marble, the payment for the work of two assistants (Cobro[?] and Babboni), the fee for the polisher and a mason, he still made a £56 profit on the bust for work that cost him 62 scudi 8 baiocchi, exchanging this rate by his own calculations to £14.38

Given how economically competitive such a price would have been, it does beg the question as to why Gibson was not tempted to make more busts for a commercial market. Here again we must conclude that Gibson was indeed in earnest when he wrote that portraiture was not, for him, a principal passion, but that he had to do it to make some money at times in his career. In another note he records that he paid his assistant Babboni 12 scudi for ‘pointing’ (roughing out in marble) the untraced bust of Mrs Hogg, adding that ‘12 sc is what Macdonald pays for all draped female busts’.39 Gibson’s comparison for labour costs was his Scottish contemporary Lawrence Macdonald (1799–1878), who was settled in Rome from 1832 onwards. Macdonald exploited the taste of expatriate visitors to Rome for portrait busts on a scale far beyond that of Gibson, producing over 150 portrait busts during his lifetime. In this instance Gibson perhaps learned the rates for pointing a bust from a colleague whose practice was much more commercially geared towards bust production than his own. Furthermore, he may have realised that he needed to charge at least that amount if he wanted to continue to assert his dominance as the leading British sculptor in Rome.

Portrait statues and polychromy

During the 1830s and 1840s, as his international reputation grew, Gibson seems to have produced fewer busts than in his younger years. It is worth reiterating that current estimates suggest a total output of no more than fifty busts in his entire career,40 as compared with over two hundred made by Chantrey (not including multiple versions of the same bust). It was at this time, however, that Gibson received commissions to execute a few important portrait statues. This practice likely related to his election to the RA as an Associate in 1833 and a full member in 1836, and undoubtedly coincided with the overall increase in sculptural production by his studio on Via della Fontanella. It is of course worth noting that this was also the period of production for some of his most famous poetic subjects, such as Venus Verticordia 1833–7 (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; this was the initial model for the Tinted Venus), the Wounded Amazon (discussed above) and the Hunter and His Dog 1847 (Usher Gallery and Collection, Lincoln). In the midst of this Gibson made three versions of his monument to William Huskisson MP in 1833–47 (including the marble version of 1836 now at Pimlico Gardens in London), as well as the memorial statue of Scottish merchant Kirkman Finlay from 1842–4 (Merchants’ House, Glasgow), the commemorative statue of Robert Peel MP for Westminster Abbey (1850–3), and other works. But statues such as these were posthumous creations for public display; thus, they arguably could be seen as extensions of funerary monuments, which Gibson also produced.41 In contrast to these works, Gibson also made portrait statues of two women modelled from life – Queen Victoria and the Hon. Mrs Henry Murray – both of which were commissions. Although these statues would be put on display, they were intended first and foremost to be private, not public, statues, thus conceptually sharing more with portrait busts than with memorial figures. Both of these statues were also tinted by Gibson, whereas none of his posthumous memorial figures ever were.

Fig.10

John Gibson

Queen Victoria 1844–7

Guard Chamber, Buckingham Palace, London

© The Royal Collection, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

The more famous of these two statues is that of the Queen, a commission that she and Prince Albert gave to Gibson in 1844, and which was exhibited at the RA in 1847 (fig.10).42 Gibson’s memoirs do not record in detail the sessions for most of those who sat for him for a portrait bust, with the exception of his first artistic encounter with the Queen. This modelling session took place at Windsor Castle during his first trip back to England since he went to Rome in 1817. On 25 October 1844 he departed for Windsor from London, where he had been staying with his friend Emily Huskisson (widow of the MP mentioned above). Reportedly nervous about this royal summons, Gibson was reassured by his hostess that he should just ‘call her Madam, and treat her like a lady’.43 According to Gibson, the Queen sat for him nine times for a total of five hours over the course of nine days.44 Their sessions were at first quiet and tense but, in a letter to his friend Rose Lawrence, Gibson recorded some of the conversations he and the Queen had, such as when she asked where he was from, thinking from his Welsh accent that he was Scottish, and whether she approved of his decision to crown her statue with a tiara, which she said she liked. He also felt compelled to comment on one of the Queen’s physical features and habits:

I wished to pay the Queen a little compliment, not upon the pretty parts of her face, but upon a defect – her ever-open mouth. Said I, ‘As the statue of your Majesty is to be represented with a scroll of paper in your hand, the lips apart, as I have expressed in the bust, will have the effect of speaking’. ‘So it will’, she said. I then added, ‘Many of the antique statues have the lips a little open; the poet says, “As if a word was hovering there”’. She laughed and seemed pleased – very. I worked very hard at the bust, and the Queen thought it was getting on well, and so did the Prince.45

Before the modelling began, Gibson was presented first to Prince Albert, with whom he conversed about art in general and with whom he expressed two concerns he had regarding the commission and his time with the Queen.46 One of these related to how the Queen was to be depicted in the statue. Gibson was relieved when the Prince told him that they wanted him to depict her ‘classically draped … like a Greek statue’.47 The second of these concerns was Gibson’s ‘habit in portrait-sculpture of measuring the features of the sitter with compasses – an operation which in the instance of Her Majesty he suggested that the Prince should perform for him’, to which the Prince assured him the Queen ‘would permit everything he might think necessary’.48

Lady Eastlake also notes that in addition to using measuring tools for the Queen’s features, Gibson ‘overcame’ the problem of her ‘shortness of stature’ by making casts of her hands and arms to emphasise her ‘most conspicuous beauties’.49 This practice of making casts of body parts from models was reportedly common in Rome. Gibson lauded his rival and friend Richard James Wyatt for his female figures and drapery, noting in particular that his working practice included ‘availing himself of as many living models as he could obtain, and he always cast the joints when these parts were beautiful in nature. Indeed the Roman sculptors make a great study of the joints, hands and feet’.50 This suggests, then, that Gibson also undoubtedly made plaster casts of various parts of the body of different models as a technique in making some of his statues, whether portrait or poetic in subject.

Fig.11

John Gibson

Statue of Hon. Mrs Murray, Later Countess Beauchamp 1842–6

Stanford Hall, Leicestershire

Photo: Roberto C. Ferrari

Another portrait statue modelled from life, two and a half years before that of the Queen, was a sculpture of the Hon. Mrs Murray, later Countess Beauchamp (fig.11), which was commissioned by her mother, the Baroness Braye.51 One early documented reference to this commission appears in a letter dated 7 May 1842, in which Gibson wrote to the poet Margaret Sandbach that he had recently been modelling a bust of a young woman but that her mother now wanted a full-length statue in marble.52 A year later the clay model for the statue was completed, and by August 1843 the plaster cast was underway.53 The widowed Mrs Murray wrote to Gibson in September 1843:

How kind of you to give Mama such an exact description of the Statue. She has no doubt the attitude you have chosen is perfect and the drapery very graceful. Every one who comes from Rome is in raptures with it as a Work of Art, and I have strong suspicions that it is so far superior in beauty to the Original that it will throw me quite into shade, so that when it arrives in England, I shall be obliged to hide my diminished head.54

Life-sized in height, the figure stands in contrapposto like the Queen, and both are clothed in thin classical drapery, although the Queen also wears a heavy mantle draped around her shoulder and body. This mantle gives the Queen’s statue the strength of character befitting a monarch and political leader, as compared to the figure of Mrs Murray, the contours of whose body are revealed through her drapery in the tradition of statues from classical antiquity. The statue of Mrs Murray shows her wearing a shawl draped around her middle and lower back, with one end of it tucked through her right arm. Her right hand clasps her left wrist, a small flower held delicately in her fingers, while her left hand holds the other end of the shawl, which cascades downwards in a series of elaborate folds, ending in an oval tassel-knot that centres the vertical axis of the figure.

Of these two works, the statue of the Queen is better known. Yet the statue of Mrs Murray may be more significant, as it was Gibson’s first portrait statue of an adult from life and arguably may have helped him envision how his statue of the Queen would compare to this one. Perhaps the most important feature of these two figures is that Gibson tinted them both. The full history of Gibson’s polychrome practice is beyond the scope of this essay, but it is worth noting that his interest in polychromy was based on recent archaeological discoveries and contemporaneous publications arguing that the ancient Greeks and Romans had coloured their statues. His experiment was about reinterpreting for a modern audience the ancient practice of tinting classical figures. Crucially important, because these two works are portrait statues, is the fact that Gibson never intended polychromy to make his statues look ‘alive’.55 Rather than tint the entire bodies of his statues, he highlighted them with colour.

The most famous of his polychrome experiments became, of course, the Tinted Venus, but the statue of the Queen was exhibited with polychromy a number of years before that particular statue was even commissioned. Gibson tinted in yellow the decorative dolphins and the bottom edge of the Queen’s tiara, as well as the decorative acorns that weighted the robe near the bottom. He also reportedly painted the sandals yellow, but then later gilded them. The embroidered trim of the robe and the details of the rose, shamrock and thistle (symbols of England, Ireland and Scotland) were made red and blue.56 Although critics were shocked by the tinting when it was shown at the RA, Prince Albert and the Queen were apparently delighted. After seeing it in a private viewing, the Prince told Gibson, ‘I am happy to say that the Queen is very much pleased with it, and so am I … colour and all’.57 They even ordered a tinted repetition for Osborne House, their rural retreat on the Isle of Wight.

In 1854 Mrs Murray (now Countess Beauchamp, widowed a second time) asked Gibson to tint her statue. This was a rather remarkable request based on the excitement conveyed to her by visitors to Rome who had just seen the recently displayed Tinted Venus in Gibson’s studio, and was also likely influenced by her memory of having seen the Queen’s coloured statue at the RA.58 Gibson described in his memoirs the colouring of this statue: ‘The head is adorned with ivy, which is gold, as well as her other ornaments; the dress is enriched with a border of red and blue, a slight flesh tint, and blue eyes.’59 The use of blue and red as highlighting on the clothing was comparable to what he had applied to his statue of the Queen. Colouring her eyes blue, however, related the statue more to the Tinted Venus.

The Countess, however, reportedly regretted her decision because some people criticised its appearance when they saw it at her home. Gibson responded to her concerns by writing: ‘Lady Beauchamp, do as I do, fight it out with them, it does not signify whether they like it or not’.60 He even invited his closest allies and friends, including Sir Charles and Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, Anna Jameson and Sir Charles Barry, to visit and convince her of its success: ‘The effect soon began to impress them agreeably, and the longer they dwelled upon the statue, the more they admired the charm of Polychromy’.61 Although the statues of both Mrs Murray and the Queen remained tinted for at least the remainder of Gibson’s life, and possibly even after the death of both sitters, the polychromy was eventually removed from these statues, reflecting changes in taste to return to a more pure, abstract form.62

‘Men thinking, and women tranquil’: The late busts

During the height of Gibson’s interest in polychrome sculpture in the 1850s and early 1860s, his production of portrait busts seems to have increased again. This may seem extraordinary considering that this was the peak of his international career and thus arguably would contradict his famous distaste for making busts in particular. But it was likely because of his position as the most famed British sculptor, albeit an expatriate one, that he was sought after to capture people’s appearances in stone. In addition, the fact that he was able to increase his prices for busts at this time to £150 demonstrates that his fame enabled him to charge higher prices and that people were willing to pay. Indeed, most of the portraits in these later years were commissions, and they occurred at a time when the market for portraiture was increasingly diffuse again after the domination of Francis Chantrey ended with his death in 1841. As a result, it was now that Gibson made some of his best-known extant busts, including the 2nd Duchess of Wellington 1856–7 (Stratfield Saye House, Hampshire); Dhuleep Singh 1859 (private collection); Sir Charles Lyell 1861–2 (private collection); Lilah Clifden 1861/2 (fig.12); Alexandra, Princess of Wales, 1844–1925 1863 (fig.13); and Edith Mozley 1863–4 (fig.14).

Fig.12

John Gibson

Lilah Clifden 1861/2

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo: Paul Highnam

Fig.13

John Gibson

Alexandra, Princess of Wales, 1844–1925 1863

Throne Room, Buckingham Palace, London

© The Royal Collection, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

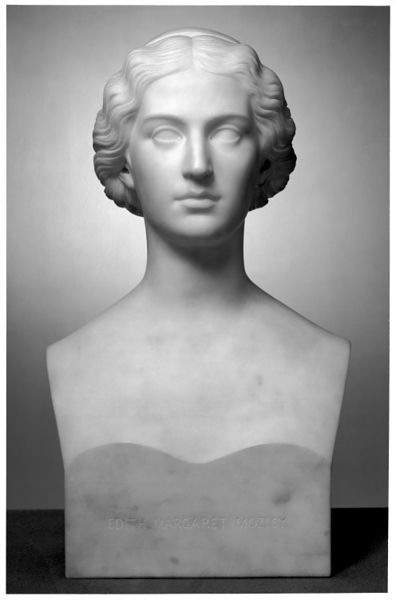

Fig.14

John Gibson

Edith Mozley 1863–4

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

When it came to the depiction of these and other individuals, whether they were statues or busts, it is well known that Gibson only accepted the commissions if he was given complete control of the artistic integrity of these works. This typically meant that the figures were to appear not in modern dress but in some form of a toga or classical drapery to enhance their timeless quality, decisions that were not unchallenged by his critics, whose eyes must have been used to the non-specific modernity of Chantrey’s draperies.63 This interest in classical style has been noted in association with the Queen’s statue in particular. But the most uncanny part of Gibson’s portrait practice, particularly at this time as he recorded his memoirs, was his determination to model only beautiful or striking features, and by this he largely meant those of women.

In late January or early February 1862 Viscount Clifden visited Gibson’s studio with his newlywed wife. Her beauty was reportedly so striking that he stopped his work on a bas relief and modelled her bust, despite his usual refusal to carry out such commissions. He recorded this incident as follows:

Lord Clifden came to me and said, ‘I am told you decline busts’. I said, ‘I do’. He expressed the greatest desire that I should undertake his Lady’s bust. When I saw her – by Jove, I was surprised when I saw such a Greek face. I said, ‘I shall model your Ladyship with delight’. Then his Lordship thanked me very much. I told her that if she lived in the time of the Greeks she would have gained the prize of beauty. I do not expect to see such another, nor one more amiable.64

Similar sentiments appear in reference to other female busts at this time. Having completed the cast of his bust of the Duchess of Wellington, Gibson wrote to her:

The study of my life has been to correct my eyes & to purify my taste by the deep study of Greek art, and he who has formed himself the most upon that only foundation is better prepared to do Justice to the likeness of a beautiful person. The Greeks considered Beauty one of the blessings from the Gods – I am sure they would have placed you among the most favored – we do.65

Similarly, upon completing the bust of the teenaged Edith Mozley, Gibson wrote her a letter quoting lines from Edmund Spenser (‘her fair locks were woven up in gold’) and Charmus the Syracusan (‘Beauty when unadorned, adorned the most’), and even stating rather boldly, ‘You are very pretty’.66

Fig.15

John Gibson

An Unknown Young Woman late 1820s

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

Fig.16

John Gibson

Rear view of An Unknown Young Woman

But Gibson’s interest in capturing the features of beautiful women dates even earlier to a bust of an unidentified woman from the late 1820s, now in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven (fig.15). The drapery sensually folds off one of this woman’s shoulders and caresses her body to reveal breasts with nipples, demonstrating Gibson’s awareness of anatomy and how the eroticism of drapery can complement the features of the human form revealed underneath. The carving of the woman’s hair is a tour-de-force of sculptural ability: waves, braids and ringlets of curls are arranged with a thin headband, framing the beauty of the woman’s face and reflecting her own attention to detail in her coiffure (fig.16). Despite the complexities of the hair in this work, the contours of this woman’s bust stand out as simple. This was indeed one of Gibson’s strengths as an artist and likely originates in his own interest in draughtsmanship.

Fig.17

John Gibson

Profile view of Grazia: Puella Capuensis c.1843

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo: Paul Highnam

Fig.18

John Gibson

Frontal view of Grazia: Puella Capuensis

Photo: Paul Highnam

Another example in which this simplistic form and fine contour is apparent can be seen in the profile view of his c.1843 bust of Grazia (fig.17), a model from Capua whom Gibson described as the ‘greatest beauty … identical in feature with the Greek ideal … the tragic grandeur of her countenance … most impressive – every part of her face was Greek’.67 In the profile view the pure outline of her face continues into her hair, which appears as a series of vertical and serpentine lines, converging into a bun at the nape of her neck. A frontal view of this bust (fig.18) also reveals one of the sculptural signatures Gibson sometimes used for his busts of women: her breasts are suggested by a double-arched line that emphasises the woman’s femininity. This affectation suggests his own version of a female herm form. Yet it is also disturbing in that the woman’s breasts are truncated or even cut off, reducing her beauty to facial features alone, and turning her into a segmented mannequin. The bust of Grazia is perhaps the most demonstrative example of this segmentation, but the double-arched line can be seen on many of Gibson’s busts of women, including those of Princess Alexandra, Viscountess Clifden and Edith Mozley. These emphasise the ‘tranquil’, feminine beauty he sought in their depictions, in contrast to the rectangular herm format he reserved for active, ‘thinking’ men.

It was not only women’s features that struck Gibson, however, as worthy of capturing in marble. Occasionally he would decide to make these portraits for himself without a commission, similar to his decision to make the Bewick bust. One rather late example of this comes from a letter Gibson wrote to the novelist and politician Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who became his friend and whose words of praise were inscribed on Gibson’s tombstone at the Non-Catholic Cemetery in Rome. After having spent a few days with Bulwer-Lytton at his country seat of Knebworth Park in August 1861, Gibson proposed modelling his portrait:

I am going to express a wish which has been upon my mind ever since I left you. – It is to model your bust when I come to England next year. If you should sit to me I venture to propose that you let yr beard grow, not too long but moderate, that ornament which God put there gives beauty & consequence to a man but the fools shave it all off that they may look like women. The bust to look straight forward & square like the Greek … I have always avoided that part of the art … But I feel – with my Greek feeling I could make a more simple & noble looking portrait of you than anything they have done.68

These descriptions and narratives about Lady Clifden, Grazia and the other women, as well as Bulwer-Lytton, all have two things in common: idealised beauty and ancient Greece. On the part of the women, Gibson is struck by their beauty as classically inspired. On the part of Bulwer-Lytton, he is struck by his beard in particular as a form of ‘beauty & consequence’ and perceives with his own classical eye how he will create a bust that is ‘simple & noble’. This interest in Bulwer-Lytton’s beard is echoed in the representation of the artist Bewick, in which the facial hair is delicately carved with close attention to detail.

For a sculptor like Gibson, who based his artistry on the exemplar of ancient Greco-Roman art, it is perhaps not surprising that he would be inspired by beauty and Greek features in both men and women. Certainly an examination of a number of his portrait busts, statues and funerary monuments demonstrates that there was clearly an interest on his part in idealising his sitters. All of his portraits show blank eyes, one of several strategies to avoid over-particularising a sitter’s look. When someone who knew the Duchess of Wellington asked why Gibson’s portrait bust of her did not give her a ‘cheerful gay look, as she appears when receiving her friends’, the sculptor replied: ‘The expression of cheerfulness and gaiety is beneath the dignity of sculpture’.69

In his memoirs Gibson praised Greek art for depicting ‘men thinking, and women tranquil’, stating that their portraits ‘look more like a superior class of beings’ and that the permanent expressions in stone appeared ‘serious and calm’.70 The last part of this quotation is noteworthy, as Gibson seems to be echoing the aesthetics of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, specifically his principle of edle Einfalt und stille Größe (noble simplicity and quiet grandeur), first conveyed in Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Mahlerei und Bildhauerkunst (Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture, 1755). Gibson was readily familiar with Winckelmann’s writings, likely through Henry Fuseli’s English translation of this text, published in 1765.71 Certainly in early nineteenth-century Rome Winckelmann’s influence on classical aesthetics was still strong. In his memoirs Gibson even points to Winckelmann as an appropriate instructor of classicism for artists: ‘Winckelmann is our modern guide in sculpture, but the attempts to produce something new have frequently led artists away from the path which Winckelmann has pointed out in his most valuable work’.72

Gibson’s notion that good portraiture should show ‘men thinking, and women tranquil’ can be read today as a form of gender bias, but this separation of the sexes into heroic men and beautiful women was both an extension of Winckelmann’s aesthetics and a reflection of nineteenth-century social norms regarding the actions and attitudes of men and women. In a letter written to his friend Sir Charles Eastlake, Gibson noted: ‘It is true that the portrait statue of a lady does not thus suffer so great a transformation as that of a man’.73 Although this was written specifically regarding his new statue of Queen Victoria, its tone is applicable to any portraits of women, rather than men, that a sculptor would make. To model a male figure required greater gravitas and heroism to exemplify his actions and principles. To model a female figure required beauty and grace.

Idealism aside, the frequent references in Gibson’s memoirs to his sitters’ satisfaction with his work, and how successfully he was able to capture their look and essence, arguably demonstrate that Gibson did not rely exclusively on idealism and classical precedent. He was also a keen observer of nature. This is not completely surprising when one realises that, despite his predominantly mythological oeuvre and his frequent comments in praise of the Greeks, he relied heavily on models – local Romans – for his poetic subjects. He even devised new rules of proportion, in collaboration with Joseph Bonomi, to convey in sculpture the complexities of the human form at rest and in motion.74 Gibson claimed to be inspired frequently by everyday scenes he saw in Rome, such as in the aforementioned observation of Roman women checking their sandals that inspired the Wounded Amazon. His sculpture The Hunter and His Dog was based on his encounter with a youth holding back his dog that was about to pounce, and after seeing a boy gazing at his reflection in the fountain at the French Academy, he created the figure of Narcissus 1838 (Royal Academy of Arts, London).75 This direct observation of nature, in tandem with Greco-Roman precedents as models of ideal beauty to be emulated, was Gibson’s artistic strength, generating a successful, if small, body of portraiture work that satisfied his patrons, despite his own lack of interest in being a portraitist.

Towards the end of his life Gibson recorded in his memoirs his thoughts on a remarkable career. It is from this later act of self-presentation, edited by Lady Eastlake and then by Thomas Matthews, that we derive many of the famously dismissive remarks by Gibson on the art of portraiture. Gibson’s mistreatment by Chantrey, his desire to distinguish his practice from that of his countrymen, the debased commerciality of portraiture, and his struggles to only produce portrait statues that reflected the classical ideal, are all outlined in these post-facto reminiscences. Against the background of this self-presentation it has proved easy for scholars to overlook Gibson’s portraiture, which in truth forms a significant body of work within his oeuvre, and reflects his friendships, his skill and his life-long search for a unity of classical poetic form and the representation of nature.