John Gibson’s studio was a well-known place in the city of Rome throughout the nineteenth century.1 Based in Via della Fontanella from 1818 to 1866, it marked a point of reference for his fellow artists as well as for visitors on the Grand Tour for almost five decades. Artists Antonio Canova, Bertel Thorvaldsen, William Turner and Frederick Leighton, as well as William Spencer Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire, his stepmother Elisabeth Forster and Prince Albert Edward, all visited the studio during their lifetimes; writers Bessie Rayner Parkes and Charles Dickens dedicated poems to the atelier. Newspaper articles, travel literature and novels narrated the visits in colourful descriptions and spread the fame of the sculptor and his studio beyond the boundaries of Rome. Yet this was no exception; during the eighteenth century many sculptors’ studios had become proper tourist attractions.2 The workshop practices fascinated visitors, leading to numerous romantic descriptions and travel accounts. Soon ‘swarms of visitors’ flooded the busy studios, in which marble flocks filled the air like ‘snowflakes’, and where hundreds of ‘masterpieces’ were produced in spacious rooms, filled with ‘gleaming sculptures’ in the atmosphere of a little ‘fairy land’.3

Fig.1

Ditlev Martens

Pope Leo 12. Visits Thorvaldsen’s Studio Near the Piazza Barberini, Rome, on St. Luke’s Day October 18th 1826 1830

Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen

An impressive amount of research has been conducted into the workshops of sculptors based in Rome in the first decades of the nineteenth century, especially on Canova.4 These analyses are mainly based on contemporary descriptions, biographies, account books and travel accounts that delineate the workshop practice in great detail. For Gibson, no such research has been carried out until now. It was mainly assumed that he continued the workshop practice of his master, Canova, without scholars extracting from the source material how exactly his workshop functioned or even what it looked like. Moreover, there is no known visual documentation of the studio, as there is for other artists’ ateliers, as can be seen, for instance, in Ditlev Martens’s painting of Thorvaldsen’s workshop from 1830 (fig.1).

The workshop of John Gibson

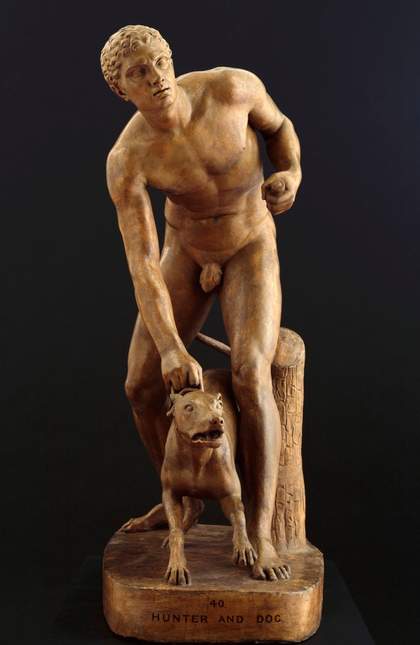

Fig.2

Pages from the inventory of John Gibson’s workshop, compiled posthumously

Royal Academy of Arts Archive, London

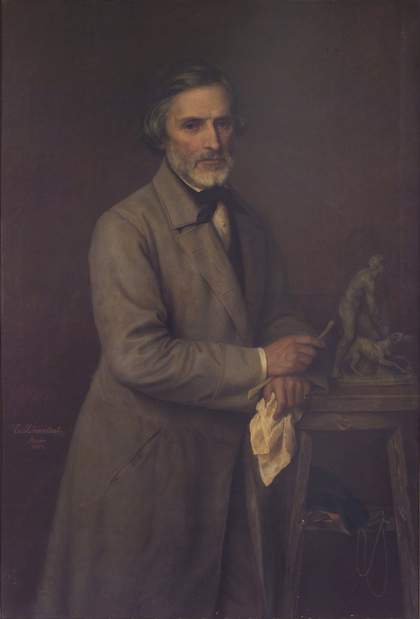

Gibson’s studio is well documented through source material that has outlived the sculptor by more than 150 years and that offers detailed information on both the workshop itself and the artist’s practice.5 The studio in Via della Fontanella was mentioned for the first time in a letter from Gibson to art collector and writer William Roscoe in 1818, and it was finally liquidated two years after Gibson’s death by the painter Penry Williams, a close friend of Gibson and executor of his will, on 8 March 1868.6 Two inventories in the Gibson Papers in the archives of the Royal Academy in London give us the most detailed information on his workshop (fig.2).7 The studio consisted of seven rooms. At least one of them, a small modelling room, was on the first floor (often referred to as ‘Canova’s Room’ and possibly the one where Harriet Hosmer used to work).8 The first room, also called studio grande, must have been of impressive scale, as it contained a large number of works: eleven full-scale plaster casts (portrait and ideal sculpture by Gibson as well as one cast after a classical work entitled A Young Boy), five marble statues, eleven portrait busts and eight reliefs. In 1866 the plaster casts of Gibson’s most prestigious work, the group of Queen Victoria with Justice and Clemency executed in marble for the Prince’s Chamber in the Houses of Parliament,9 as well as the plaster model of his Hunter and Dog 1847 (fig.3), were displayed in the studio grande.

Fig.3

John Gibson

Hunter and Dog 1847

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo: Paul Highnam

Three marble versions of Hebe, Greek goddess of youth, all from c.1860 and one of which was coloured,10 were placed with one of his first plasters, Mars and Cupid c.1818 (untraced). From the studio grande, visitors had to cross a courtyard with a fountain in order to enter a camerino scuro – a small dark entrance hall – followed by a camerino containing mainly plaster casts after classical works, from which stairs led to the camerino di sopra (the small room on the upper floor). In the fourth room downstairs, camera 4, were sixteen life-sized plaster models of Gibson’s most famous ideal sculptures, such as the Wounded Amazon 1840 (untraced), Paris 1819 (untraced), Bacchus 1856 (untraced), Flora 1830, the Sleeping Shepherd Boy 1818 and the undated Tinted Venus (all Royal Academy of Arts, London). Also placed in camera 4 were marble versions of the Tinted Venus (undated; Royal Academy of Arts, London), Bacchus 1856 (Royal Academy of Arts, London) and the Dancer (undated; untraced).11 In camera 5 were displayed plaster casts of classical works, such as the Medici Venus from the 1st century BC (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence), as well as the plaster model of Theseus and the Robber 1865 (untraced), Gibson’s last work. The sixth and seventh room, camera 6 and camera 7, contained earlier works such as two marble versions of Hunter and Dog and the models of his latest compositions, such as Nymph and Amor 1862 (National Museum of Wales, Cardiff), the Wounded Warrior 1860s (Royal Academy of Arts, London) and Psyche and Cerberus c.1860 (Royal Academy of Arts, London). Within the inventories, nearly 150 works are listed, including ten marble statues, fifty plaster statues, thirty busts in plaster, fifty-four reliefs in plaster and five reliefs in marble. The impressive number of models and statues testifies to the prolific output of Gibson’s workshop.

Gibson’s studio practice

It is well known that in the first half of the nineteenth century, Rome was a dynamic centre for the production of sculpture thanks to inventions in the second half of the previous century.12 Copyists and restorers of classical statues, such as Bartolommeo Cavaceppi, had established working methods that enabled them to produce high-quality copies of classical works or reductions and enlargements of any three-dimensional prototype.13 The copyists followed technical innovations for the reproduction of classical statues developed at the French Academy in Rome, described in Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie in 1765.14 Similar techniques were also passed on by Francesco Carradori in his Istruzione elementare per gli studiosi della scultura, published in 1802, with prints by Carlo Lasinio.15 Antonio Canova, who had frequented the studio of Cavaceppi and read Carradori, described the working methods in his diaries as extremely laborious and time consuming.16 However, he still used the technical innovations for the benefit of the production of his own works, through reintroducing the use of large-scale clay models that were cast in plaster and then transferred by his assistants to the marble block.17 The process reduced the participation of the sculptor in the realisation of the sculptures to the execution of presentational drawings,18 bozzetti (rough sketches made of clay or wax) and small-scale models, whereas the enlargement to full-scale models, the casting of the plaster models, the uplifting, preparing and carving of the marble block, as well as the execution of details and attributes, were all tasks left to specialists.19 Canova gave not only the finishing touches – l’ultima mano – to the marble, but he was also involved in the process of carving. This became increasingly unusual for Roman sculptors from the 1820s onwards.

Fig.4

Penry Williams

Portrait of John Gibson 1845

Accademia di San Luca, Rome

Fig.5

Emil Löwenthal

Portrait of John Gibson 1864

Accademia di San Luca, Rome

Gibson’s workshop practice was similar to this, and a large number of his compositional sketches and drawings are conserved within the collection of prints and drawings at the Royal Academy in London.20 Many of them seem to be pages removed from small pocket-sized sketch books that Gibson might have carried around with him. The compositions of the drawings were transferred to small three-dimensional sketches. Even though there are no traces of any surviving small-scale models made by Gibson (apart from a very early plaster now in the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff),21 his work with small-scale bozzetti and modelli is documented in the source material. Throughout his career, portraitists depicted Gibson as modeller, holding modelling tools in his hand, usually with a small-scale clay composition in the background.22 In the mid-1840s Penry Williams portrayed him with a spatula and a small clay model of Cupid Tormenting the Soul (fig.4). His German colleague Emil Löwenthal painted a very similar likeness of Gibson in 1864, showing the by then aged artist with the small model of Hunter and Dog (fig.5). Written sources document a similar model for Gibson’s last and unfinished work, Theseus and the Robber.23 According to these papers, at the time of his death he left a finished bozzetto and a small-scale model of the composition. The bozzetto was sold through auction, with some of the equipment from the studio and some duplicate works. The small model was left to his pupil Harriet Hosmer.

Fig.6

John Gibson

Psyche and Cerberus 1860

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo: Anna Frasca-Rath

Fig.7

John Gibson

Monument to Lady Leicester: Angel Carrying Infant and Leading Mother to Heaven c.1844

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo: Paul Highnam

Fig.8

John Gibson

Rear view of Monument to Lady Leicester

Photo: Anna Frasca-Rath

Moreover, the documents relating to Theseus reveal how advanced the workshop practice had become by the time of Gibson’s death. Williams and a group of friends tried to convince William Boxall, a fellow executor of Gibson’s will, and the Royal Academy of Arts to pay for the execution of the full-scale marble group posthumously, as Gibson’s last work. The caster Filippo Malpiere was paid for the execution of a large-scale clay model and its plaster cast (although it was never translated to marble). Gibson’s models within the collection of the Royal Academy suggest that the technique for making the plaster casts was similar to the one documented for Canova: the use of a metal skeleton as well as crosses of wood and wire to support the heavy clay.24 The broken model of Psyche and Cerberus, for example, reveals parts of the inner structures including the crosses of wood that attached fragile elements such as wings or hands to the larger body of the statue (fig.6). A similar process was used for the production of clay and plaster models for reliefs. The soft materials were applied on structures and frames of a more solid quality, as is clearly visible on the back of the plaster relief for the Monument to Lady Leicester: Angel Carrying Infant and Leading Mother to Heaven c.1844 (figs.7–8). However, Gibson’s models are substantially different to the plaster models by Canova that are on display at the Museo Canova in Possagno, as the actual number of points that were necessary for the pointing are few and much smaller. Very few metal points remained on Gibson’s plaster models at all, as after Gibson’s death Malpiere was paid to take off the ‘pins’ and restore the models.25 However, not all of the plaster casts within the collection of the Royal Academy functioned as modelli. Some of them were ricordi (records) of works that were sent to their commissioners. The difference can be seen in the surface of the works and the background is not perfectly flat but slightly uneven. Some of them, for example The Meeting of Hero and Leander (fig.9), are cast from a clay model and it is possible to identify the traces of the modelling tools, especially in the hair and the drapery of the figures. The plaster cast of The Marriage of Psyche and Celestial Love (fig.10), in contrast, was taken from the marble version to be sent to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Such details as hair and drapery reveal the sharp and defined contours of the marble relief.

Fig.9

John Gibson

The Meeting of Hero and Leander 1842

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo: Paul Highnam

Fig.10

John Gibson

The Marriage of Psyche and Celestial Love 1844

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo: Paul Highnam

In the next step, the plaster models were transferred to marble by pointers, who roughed out the block. Afterwards, the final form was worked out by carvers and the surface perfected by polishers. It is not possible to deduce from the written accounts to what extent Gibson was involved in this process, as there does not seem to be any visual or source material related to this. What we do know is that, unlike Thorvaldsen, Gibson kept to Canova’s practise of making the finishing touches to the work. He also experimented throughout his career with the colouring of his sculptures.26 However, little is known about the exact recipe of the colour, made up of wax and pigments, that he developed in collaboration with Penry Williams and from his study of classical texts. Gibson recorded a great number of quotations extracted from ancient and modern literature on the polychromy of ancient works. We know from his letters that the colour could be removed easily from the statues with a sponge, soap and water.27 Further analyses of the versions of Tinted Venus or Pandora 1860 (Lady Lever Art Gallery, Liverpool) could reveal more details about this practice.

In total, nine phases can be identified for the process of sculpture making in Gibson’s workshop: 1) finalising the composition through sketches and drawings; 2) the execution of three-dimensional sketches (bozzetti) and their transfer to a more distinguished preliminary small-scale modello; 3) the enlargement to a full-scale clay model from which a plaster cast was taken; 4) the roughing out of the marble block through pointing; 5) completion of the marble statue by a carver; 6) the polishing of the work; 7) the final polish and the tinting of the marble; 8) in some cases, the making of a cast of the final marble to be kept as a ricordo in the workshop; 9) the reproduction of the model or ricordo.

Shipping and installation

When a work was finished, it had to be shipped and installed. Almost all of Gibson’s sculptures – apart from the group Psyche and the Zephyrs, made sometime before 1841 for the Torlonia family (Galleria Corsini, Rome) – were exported from Rome. The statues were packed in his studio and brought to the port of Leghorn, from where they were shipped to their destination. Gibson noted the costs for shipping a statue of William Huskisson with logistics company Mess. Freeborn in ‘a large case embedded with oil cloth and canvas’ as amounting to £47.28 The shipping of the simpler case for the pedestal cost £12, and sending a cast of the Huskisson statue to London cost £41.29

Another logistics company mentioned quite frequently is that of Mr McCracken. Before the arrival of the work, plans for the pedestals, as well as suggestions for the arrangements were sent to the patron. In many cases, sculptors, including Francis Chantrey, Richard Westmacott, William Theed or even Gibson’s brother Benjamin, were present when the wooden packages were opened and any damages were documented.30 In the case of Pandora, a statue commissioned by George Lawrence and completed in 1861, the commissioner was advised to attend its arrival in Liverpool in order ‘that they [the employees of McCracken] do not injure the statue when they examine into the case’.31 The sculptor reaffirmed that ‘Mr. McCracken said that he has his Agent there who will be present, still, you [George Lawrence] had better look after it’.32 The sculptor’s advice on the installation of the work was as follows:

When the pedestal is placed, and the upright case placed near it, remove the boards from the front and back. Then the front & back is open, but the sides, top & bottom still undisturbed, so that the statue is firm inside. When placed close in front of pedestal raise it by degrees, placing short boards one upon another till the bottom of the plinth of the statue is exactly level with the surface of the top of the pedestal. When thus placed cut away the box, and then draw the statue on its pedestal, taking care that the men have towels between their hand and the statue.33

The careful instructions provide a vivid impression of Gibson’s business processes and the care taken in the transportation of the statues, from the studio, to the delivery, to the vendor.

Workers and costs

Fig.11

Bertel Thorvaldsen

Hylas and the Water Nymphs c.1832

Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen

Five account books in the archives of the Royal Academy provide a profound insight into the operations of Gibson’s studio,34 as the artist meticulously documented the workmen employed, the length of time they spent working for him and the fees paid.35 The laborious and time-consuming working processes of the eighteenth century had been, by the time Gibson was working, accelerated and replaced by a finely honed division of labour. The account books show that only a few collaborators, such as the carver Felice Baini36 or a pointer listed as ‘Babboni’, worked on a regular basis for Gibson, whereas a number of unnamed persons were employed for the standardised jobs of plaster casting, pointing and polishing. As mentioned earlier, details such as hair and wings (for instance those of Cupid in The Marriage of Cupid and Psyche) or attributes such as vases or helmets, were often left to be completed by these anonymous specialists who rotated within the Roman studios.37 The prices ranged from 2 scudi for a fig leaf to 30 scudi for a pair of wings.38 The specialisation of the stone carvers resulted in a constant level of workmanship and the consequent high quality of the sculpture made in Rome. It was often the same hands that worked the marble within different workshops. We know from Gibson’s account books that the carving of the relief of Hero and Leander, ordered by the 6th Duke of Devonshire and placed at Chatsworth House in 1842, took forty-five and a half days and cost 165 scudi, 8 baiocchi, and was executed by Felice Baini. Baini was also employed in the workshop of Bertel Thorvaldsen, who produced work on a much larger scale than Gibson. It is therefore not surprising that some of Thorvaldsen’s works, for example the marble relief of Hylas and the Water Nymphs c.1832 (fig.11), show a very close stylistic relationship to Gibson’s works. This division of labour was not limited to the boundaries of Rome. When Gibson received the order for the bronze portrait statue of William Huskisson in 1845,39 he accumulated information about the costs for bronze casting in different workshops throughout Europe, such as the French metal foundry Eck and Durand.40 The bronze statue of William Huskisson was finally cast in Munich in the workshop of Ferdinand von Miller, who had established, according to the Builder, a new method ‘by the use of different sorts of files … a real advance in the mechanism of the bronze founding process’.41

Prices and profit

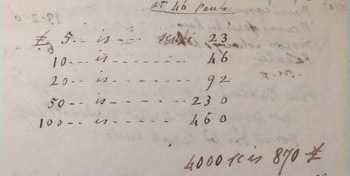

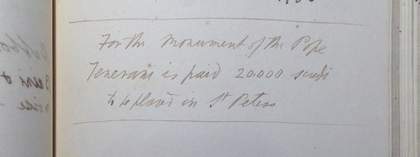

Fig.12

Excerpt from John Gibson’s account book, c.1822–59

Account Book 2, RAA/GI/6/2, Royal Academy of Arts Archive, London

The account books also contain information on profit margins and exchange rates from pounds to scudi (fig.12) and reveal much about Gibson’s skills as businessman. He was well informed about the prices charged by his colleagues and made notes about the 20,000 scudi that were paid to Pietro Tenerani for his papal monument in St Peter’s (fig.13). Moreover, he documented the prices of statues produced back in Britain, such as the bronze statue of Admiral Nelson now in Trafalgar Square made by Edward Hodges Baily for £4,000, or an unidentified statue of Sir Pulteney Malcolm, also by Baily, ‘who has to have for it including Pedestal £1,000’.42

Fig.13

Excerpt from John Gibson’s account book, c.1822–59

Account Book 2, RAA/GI/6/2, Royal Academy of Arts Archive, London

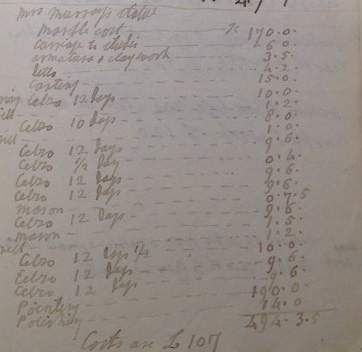

Gibson’s personal price policy can be highlighted through the following two examples. The first, the portrait statue of sculpture of the Hon. Mrs Murray, later Countess Beauchamp, was ordered in 1845 and placed at Stanford Hall in Leicestershire. For this Gibson calculated marble costs (170 scudi), the carriage for the transport of the block to the studio (6 scudi), the armature and clay work for the large clay model (3 scudi, 5 baiocchi), the casting of the large plaster model (4 scudi, 2 baiocchi), the pointing (190 scudi) and the polishing (14 scudi). A certain ‘Celso’ spent 97 days carving the statue (86 scudi, 6 baiocchi) and also Baini received another 22 scudi and 9 baiocchi for carving (fig.14). The sum of all costs was equal to 494 scudi, 3 baiocchi, 5 quattrini or, according to Gibson, £107, and the work was sold for £500.

Fig.14

Excerpt from John Gibson’s account book, c.1822–59

Account Book 2, RAA/GI/6/2, Royal Academy of Arts Archive, London

Even greater was his profit from the second example: the portrait statue of Kirkman Finlay 1842–4, priced £1,200 and placed in the Merchants House, Glasgow. The production costs were £200 or 914 scudi according to the account books. Gibson paid 400 scudi for the block of marble, which was almost equal to the pointing and carving, which totalled 408 scudi. The additional costs were relatively low: for the mason (15 scudi), the boy putting in the drill (8 scudi), the polisher (10 scudi), the making of the model (13 scudi) and the casting of the large model (60 scudi). According to Gibson’s calculations, £200 was the average cost for a ‘sitting portrait statue of 6 feet’ and he lists the statues of Bishop van Mildert for Durham Cathedral at £202 (priced £1,200), the first portrait statue of William Huskisson at 7 feet for £200 (priced £1,200), the second version at £340, and the costs for the marble and work of Hunter and Dog for £120.

How much Gibson earned throughout his career in his business practice can be calculated from his books, where he lists the impressive numbers of reproductions and versions.43 He held marble versions of his most famous works in stock so that they were available for immediate purchase by his international clients.44 Apart from full-size sculptures, it was possible to acquire busts of his ideal sculptures for a lower price,45 and the offers were adjusted to the client’s wishes. Thanks to this working process, Gibson produced 350 plaster models, ideal sculptures, funerary monuments and busts during the forty-eight years he resided in Rome. He charged prices in an almost standardised way: £30 to £40 for ideal busts, £45 to £70 for portrait busts, £100 to £200 for reliefs and £250 to £1,000 for ideal sculptures, depending on the measurements, number of figures and patron. Even though he repeatedly stated he worked for eternal fame and not for money,46 he left several calculations of his profits within the account books.47 In 1836, for example, he had made a profit of £1,225 by selling portrait and ideal busts and he had earned more than £1,000 through the various repetitions of the Cupid Disguised as Shepherd Boy.48

Despite the detailed notes on production costs and prices, further research is needed on exactly how the financial transactions between Gibson and his patrons evolved. However, the documents in the archives of the Royal Academy of Arts, the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, and the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, do show that many transactions were made through London-based bank Baring Brothers and Co., where Gibson held an account.49 The money that was paid in London could be withdrawn at the bank of the Torlonia family in Rome.50 There are many documented cases of transactions in which a certain amount of the sum was paid in advance and the rest was paid after the arrival of the statue.

Via della Fontanella 4 in contemporary literature

Gibson’s studio was not only a workshop, but also an attraction for travellers to Rome. A growing interest in the Roman ateliers is mirrored in contemporary guidebooks, such as Enrico Keller’s List of Roman Studios from 1824 and 1830, Count Hawks Le Grices’s Walk Through the Studii from 1841 and F. Saverio Bonfigli’s Guide to the Studios in Rome from the 1860s, which provide long lists of addresses and occasional background information on the artists, their works and patrons.51 But this interest in the Roman studios was not limited to the borders of the city. The vivid curiosity of British readers is deducible from the great number of descriptions published within newspapers and contemporary literature, such as ‘A Peep into the Artist’s Studio in Rome’ in the New Monthly Magazine in 1854.52 Many travel accounts were written in the second half of the century and the Roman workshops repeatedly appeared as settings within romances and contemporary literature, as in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Marble Faun (1860). His detailed description of the workshop of the young American sculptor Keynon, which includes the observation that ‘the sculpture-rooms within had formerly been occupied by the illustrious artist Canova’,53 characterises this workshop as a

rough and dreary-looking place with a good deal the aspect, indeed of a stone mason’s workshop. Bare floors of brick or plank, and plaistered walls; an old chair or tow, or perhaps only a block of marble (containing, however, the possibility of ideal grace within it) to sit down upon; some hastily scrawled sketches of nude figures on the white wash of the wall.

There are several descriptions of Gibson’s workshop within contemporary literature. Matilda Hays, for example, gives a description of a visit of the Lutterells, protagonists of her novel Adrienne Hope (1866).54

Their [Lord and Lady Lutterell’s] ring at the shabby, worm-eaten door – a whip-cord, with a knot at the end being the primitive arrangement by which the bell was set in motion – was speedily answered, while the immediate recognition of their name showed that they were expected. The transition from the dirty unfragrant street to the cool large studio, filled with the lovely statues and bassi rilievi, with a green vista of moss and fern and trickling water beyond, and the scent of the rich flowers of the south wafted on the breeze, was a pleasant surprise to both, eyes and nose.55

The New Monthly Magazine tells its readers about ‘an unfloored room, in which are crowded numerous statues, casts, busts, and basso relieves; whilst the workmen are busy on others’,56 whereas the writer and historian Charles Richard Weld, who visited Gibson’s workshop in the early 1860s, describes the studio as a crowded and busy place, ‘generally … full on wet days, when the studios are sure to be besieged by swarms of visitors’.57 Similar accounts of Roman ateliers were made by Joseph von Kopf, who recorded in his Lebenserinnerungen eines Bildhauers of 1899 that there were crowds of carriages in the small side street, belonging to the English and American tourists who were convinced – due to their lack of taste, as Kopf noted – that Gibson was the greatest artist in Rome.58

More importance was given to the fact that Gibson’s studio was a tourist attraction. The New Monthly Magazine informed its readers that it was ‘the greatest attraction’ in the winter of 1854,59 when the sculptor polarised the Roman audience with his Tinted Venus, which was said to be the most discussed work in the ‘tea-fights’ (or tea parties).60 It is, therefore, not surprising that his works in general and his polychrome works in particular were of great interest for the audience. Hawthorne refers directly to the Tinted Venus by Gibson;61 Hays describes how Lord and Lady Lutterell took a close look at the artwork, accompanied by the artist:

Round and round the pedestal on which the Venus was mounted, the master and his guests slowly moved, viewing the statue from all points and at all distances, for the delight of the artist with this, the first result of a long cherished plan, was naïve and artless to the last degree, and he met the bantering of fellow artists and friends with a spirit of complacent self-satisfaction, which entirely robbed all criticism of its sting, and rendered its subject invulnerable.62

The encounter with the Tinted Venus also marked a lively description in the New Monthly Magazine of the presentation of the work, set on a pedestal and surrounded by chairs, which offered the visitors the possibility to admire it at their leisure.63 The statue was covered with ‘a thin gauze veil which the attendant dexterously whips off the Venus’.64 More mundane is the discussion on the polychrome sculpture offered by Weld, who refers to the colouring of sculpture during his description of Psyche and Cerberus, the sculpture on which the artist was working during Weld’s visit. The author asked the sculptor whether he was going to colour the statue, to which the answer was, ‘Indeed, I will’.65 This short statement is followed by a long discourse with Gibson about the colouring of statues in general and Psyche and Tinted Venus in particular.

These published accounts of Gibson’s polychrome works highlight the personal relationship that the authors had with the artist, and their writings offered Gibson the opportunity to express his personal opinion of art history debates to a broader audience. Moreover, they presented his statements in combination with positive descriptions of the artist himself and his character, introducing a personal note to the theoretical contents. Weld notes that Gibson ‘received me kindly, and invited me to visit him within his studio whenever I felt inclined’.66 The artist’s kindness towards his visitors is also depicted within Hay’s novel, where he is described as modest, intellectual and of taciturn character, but ‘eloquent, so altogether charming’ when speaking about his artworks – above all the Tinted Venus.

Gibson’s studio in poetry

There are also two poems about Gibson’s studio, by Bessie Parkes and by Charles Dickens.67 Parkes, who was from Birmingham, was a journalist and campaigner for women’s rights. She established the English Woman’s Journal with the support of Anna Jameson and Matilda Hays, and became a co-editor.68 Parkes might have known Gibson through Jameson, her mentor, who mainly published non-fiction prose such as art criticism, travel writing, history and biography.69 Jameson was a lifelong friend and biographer of Gibson. Parkes’s poem ‘Gibson’s Studio’, published by the English Woman’s Journal in August 1859, describes the studio as an island of peace and retreat within the city of Rome. Dickens published his poem, also entitled ‘Gibson’s Studio’, on the basso relievo of The Hours Leading the Horses of the Sun 1850 (Royal Academy of Arts, London). Dickens’s poem offers colourful interpretations of Gibson’s sculptures, without any references to the studio itself, focusing instead on the atmosphere within the workshop.

The poems tie in with the tradition of poetry about sculpture that has existed since antiquity.70 They offer an insight into the large network of people who frequented Gibson’s workshop during the nineteenth century and reflect their immense variety – ranging from famous authors such as Dickens to lesser-known ones such as Weld. They are, moreover, an important source for understanding the reputation of the artist and his works among his contemporaries, and demonstrate the faithful interest British writers and audiences had in their famous expatriate countryman.

The few examples from literature and poetry show that the articles, travel accounts and poems concentrated on the artist himself and on the studio as a space of artistic ideas, not as a workshop. What they reveal is the interest of nineteenth-century writers and readers in the artist’s character. This is realised through descriptions of Gibson’s manners and his thoughts, as in the case of Weld or Hay. There seems to have been little interest, however, in the technical aspects, and the innovations or industriousness of his workers. That these methods were already familiar to his contemporaries can be deduced from Hawthorne, who describes the ‘class of men [in Italy] whose merely mechanical skill’ makes them ‘nameless machines in human shape’ and he states that ‘in no other art, surely, does genius find such effective instruments, and so happily relieve itself of the drudgery of actual performance’.71

Emphasis is given by many of the authors to the expression of Gibson’s artistic genius in his works. This interest in genius at a more general level is also reflected in Hawthorne’s detailed descriptions of the sculptor’s models, the ‘intimate production of the sculptor himself, moulded throughout with his loving hands, and nearest to his imagination and heart’.72 Similar thoughts are mirrored in the descriptions by Parkes and Dickens of Gibson’s studio as the home of ‘the gods of Hellas’ and in the wish that ‘workmen shall live forever’ in his works.73 The literary depictions and poetical accounts of Gibson’s studio rank next to the countless depictions of painters and sculptors, such as Giotto, Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo, that present the artists surrounded by patrons, admirers and copies of their most famous works.74 Like these images, the written accounts are no more than an attempt to celebrate the genius of the artist and to romanticise a profession, in times of the increasing industrialisation of art, of mass production and of the idea of artists as entrepreneurs.

The source material analysed here presents Gibson as a very successful and judicious entrepreneur. His workshop efficiently produced works of high quality, the profit margins were considerably high and processes were standardised. The local conditions were favourable: human labour was relatively cheap, resources such as marble were readily available, and Rome had a surfeit of commissioners in the form of aristocratic or bourgeois Grand Tourists. All sources mirror the growing significance of the artist’s studio throughout the nineteenth century and are important documents with regard to the cultural and social history of the time.75

The artist’s studio was subject to a semantic change over that whole period. From a contemplative space of creative activity, it was transformed into a highly efficient workshop, a tourist attraction and finally turned into a fashionable meeting place by the end of the century.76 This change was not a linear process, but rather resulted from simultaneous changes. It thereby led to contradictions and tensions in the definition of the studio as an extremely productive and almost industrialised workshop, showroom or salesroom, against the idea of the studio as a romanticised place of creativity. A corresponding tension is found within the self-image of the artist, oscillating between entrepreneur and creative mind.