As both an academic and museum practitioner I have been aware of the differing challenges and expectations of working in both museums and academia for a number of years. Furthermore, from conversations with peers in both sectors it is apparent that there is often a baseline misunderstanding of each other’s pressures. Many former colleagues in the cultural sector have opened up about why they find it difficult to work with universities and academics. Relevance is a reoccurring theme; there is a view that academics use ‘fancy language’ but do not actually know what it is like to work on the ‘front line’. An obvious counter-argument to this is that museum and arts professionals are often not aware of the pressures of working in academia, and perhaps it is exactly these contradictory pressures and work cycles that create this tension between academia and the museum sector (and indeed other knowledge-based industries). What follows is a critical examination of how museums and universities, individual art professionals and academics, engage, work and collaborate with each other. More specifically, this article addresses the question: should museum studies as a discipline be concerned with recording and critiquing established practice, or should its focus be on influencing positive and progressive change within the sector? The geographic scope of this investigation is limited to the UK context because the operating environments of the higher education and museum sectors within the UK play a major role in shaping museum studies. Annette Jael Lehmann and Anna-Lena Werner have argued the need for a shared practice-based methodology to overcome ‘a biased gap between theory and practice, where knowledge production and theoretical reflections by academia tend to be divided from practical tasks of the museum’s operational spheres of display and exhibition’.1 Indeed, what many museums studies graduates find difficult is transitioning from thinking about practice to becoming practitioners themselves, particularly within a competitive job market. Critical praxis brings the spheres of theory and practice together, and as such presents a theoretical framework from which to challenge such tensions.

How research is disseminated, including the language and publication platforms used by academics, became a key aspect of this investigation. Given the amount of research that is published in pay-walled journals (although admittedly this is something that is beginning to change), it is not surprising that some museum professionals are unfamiliar with the work of museum studies academics. The foundation of this paper is a literature review of existing research that examines the interplay between museums and universities in developing practice-based research and teaching. This literature review and analysis of existing practice forms a critical foundation from which two action research projects are developed. The first project took the form of a twelve-hour hackathon at the Ulster Museum, and the second a three-hour digital skills workshop at the Wellcome Collection in London. Both these projects applied an iterative methodology to developing and testing scalable approaches to critical praxis pedagogy, which could be used by academics in a range of teaching environments. The aim of such an approach was to develop ways to support students in the transition from thinking about museum practice to becoming active, engaged and innovative practitioners.

Theory versus practice

While there are many recognised and widely accepted definitions of a museum, the definition of museum studies as an academic discipline is perhaps more nuanced. It is traditionally understood as a broad academic area of enquiry that seeks to identify, record and critique the culture of museums and their working practices. The primary aim of this approach, which could be described as critical museology, is not to bring about change in museums, but to broaden the wider body of knowledge on the complex, political and biased nature of the museum as a social construct. Anthropologist Anthony Shelton, who has over twenty-five years’ experience working as an academic within this area, has drawn a distinction between ‘critical museology’ as an exercise in intellectual curiosity and museums studies, which is concerned with operational practice.2 Scholars Vikki McCall and Clive Gray have also argued that the aim of museum studies (and the associated programmes that have emerged from it) is to provide students with a well-rounded education, with students using this training as a means to gain an entry-level position in a museum from where they would begin to develop technical skills.3 Peter H. Welsh, Director of Museum Studies at the University of Kansas, argues that a singular approach to theorising museums is problematic, because museums are operational and active institutions. Welsh observes that it would be ‘far less messy if museums … existed in a world of ideas and concepts’, but the reality of museum work is much more practical.4

Conversations around the divide between academic and technical practices undertaken within museums studies research and teaching are not new. In The Development of Museum Studies in Universities: From Technical Training to Critical Museology, Jesus-Pedro Lorente, Professor of Art History at the University of Zaragoza, notes that Raymond Singleton, the founder of the School of Museum Studies at the University of Leicester, preferred ‘museum studies’ rather than ‘museology’ because he ‘detested the endless debates on the theory of museology’.5 Singleton advocated a technical training, and Lorente notes the irony of this position, as the School of Museum Studies is now recognised as a world leader in academic research on the museum, its collection and audience, rather than as a centre for technical training for the sector.6 While the School of Museum Studies at Leicester was established in 1966, museum studies programmes did not develop in America until the 1970s and 1980s.

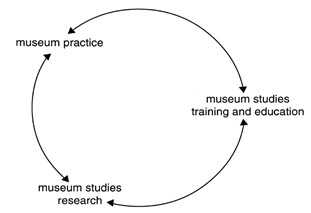

Fig.1

Conceptual model for thinking about museum studies

Reproduced in Suzanne MacLeod, ‘Making Museum Studies: Training, Education, Research and Practice’, Museum Management and Curatorship, vol.19, no.1, 2001, p.51

In addressing this ‘theory vs. practice dichotomy’ Suzanne MacLeod, Professor of Museum Studies at the University of Leicester, takes a broader view of museum studies and incorporates the ‘complex web of relationships and working practices which currently characterise museum studies’ into a new conceptual model.7 The model developed by MacLeod presents the idea of museums studies as a forum, rather than a purely academic pursuit. Her model incorporates a broad range of activities from education to museum practice and sees each as integral to the continued development of the museum studies discipline (fig.1).8

MacLeod developed her conceptual model to provide a more valid understanding of the role of museum studies, which she sees as having ‘an active role in the redefinition of the museum over the last three decades’.9 MacLeod’s model moves forwards long-standing arguments about theory and practice towards a more iterative model, which presents museum studies as an evolving discipline shaped in equal parts by training and education, research, and museum practice. Like MacLeod, Lynne Teather also places an emphasis on the relationship between research, education and practice, and suggests that museum studies should move away from global studies of museums (museology) towards more specific research on ‘internal and external operations and management’ (museum studies).10 While recognising the value of museological critique, Teather advocates the need for museum studies as a discipline to value ‘the everyday’ skills and expertise required to run a museum: ‘It is the combination of the museum process and museum skills that frames the field of museum studies’.11

The work of educational theorist Etienne Wenger on ‘communities of practice’ is highlighted within MacLeod’s paper as a means to support the argument that the different components of museum studies – teaching, practice and research – can benefit from working together.12 Wenger defines communities of practice as groups of people who share a similar drive or motivation to develop themselves and or the organisation in which they work. MacLeod uses this learning theory as the basis of her conclusion:

A recognition of museum studies as training and education, research and practice, and as an area of enquiry made meaningful through participation and collaboration enables us to recognise museum studies as an integral aspect of the current museum scene, one which can make a valuable contribution to the shaping and placing of museums in contemporary society.13

It is probably fair to say that museum studies programmes, like museums themselves, have changed radically in the last ten years, with a greater focus on employability and skills-based training. However, like museums, museum studies programmes must continue to adapt if they are to prepare young professionals for the ever changing, ever more complex policy context in which museums operate.

Museum studies and methodological inventiveness

Taking the stance that museum studies should be a people-orientated discipline made up in equal parts by museum practice, training, education and research this paper seeks to adopt and adapt action research methods to create a model of museum studies as a critical praxis. Methodological inventiveness – the creation of new research methods or the altering of existing methods – is an established practice within education and healthcare, particularly within action research projects where such methods support the development of solution-based research outcomes. This approach empowers both practitioners and service users to design solutions to problems and as a result empowers them to confidently support the resultant ‘implementation activities’.14 Education theorists Marion Dadds and Susan Hart have studied the value of research from the perspective of a practitioner or service-user, rather than from that of an academic, and have outlined the significance of this approach:

Practitioner research methodologies are with us to serve professional practices. So what genuinely matters are the purposes of practice that the research seeks to serve, and the integrity with which the practitioner researcher makes methodological choices about ways of achieving those purposes. No methodology is, or should be, cast in stone, if we accept that professional intention should be informing research processes, not pre-set ideas about methods of techniques.15

Dadds and Hart speak of the need to create conditions, which facilitate and encourage ‘methodological inventiveness’:

If our aim is to create conditions that facilitate methodological inventiveness, we need to ensure as far as possible that our pedagogical approaches match the message that we seek to communicate. More important than adhering to any specific methodological approach, be it that of traditional social science or traditional action research, may be the willingness and courage of practitioners ‘and those who support them’ to create enquiry approaches that enable new, valid understandings to develop; understandings that empower practitioners to improve their work.16

Central to Dadds’s and Harts’s argument is the need to develop pedagogic practices that support risk, as risk is an essential component for the development of methodologically inventive research methods. Kathleen Fitzpatrick, Director of Digital Humanities at Michigan State University, also writes about the need to ‘make sure someone’s got your back’.17 In a 2011 article she talks about the challenges facing early career academics that seek to use new technologies and novel methods of research. Fitzpatrick talks about how ‘digital scholars run the risk of burnout from having to produce twice as much traditional scholarship and digital projects as their counterparts do’.18 Her advice is that such methods can only really be developed or implemented if researchers know ‘that their senior colleagues will learn to evaluate new kinds of work on its own merits and will insist upon the value of such innovation for the field and for the institution’.19 The challenge for those not in an environment that encourages or supports risk is to innovate in order to achieve social change within accepted parameters.

Rather than being driven by academic expectations (which could be called critical museology), and established methodologies, the critical praxis pedagogy proposed in this paper takes a more inventive approach to developing research methods. It does not rely on research or teaching methods that carry the most academic weighting or precedence, but on inventiveness, risk-taking and innovative approaches designed to respond to the challenges that exist within the museum sector.

For museum studies to truly become a discipline grounded in critical praxis, the pedagogy that supports this model needs to be realistic, scalable and deliverable. As a means to explore how this approach could tangibly be realised, two action research projects were carried out between 2012 and 2016 with students at the University of Ulster and Richmond University: The American International University in London. This paper will now explore these two case studies in turn as potential models for critical praxis pedagogy, which could be adopted and adapted by those working at the intersection of academia and museum practice.

1: Developing critical praxis at the Ulster Museum

With Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s article about the digital humanities in mind, it is fair to say that the museum sector in Northern Ireland was slow to respond to digital technologies. In 2012 the only dedicated ‘digital’ post in any museum was that of the web marketing manager at National Museums Northern Ireland. Through informal conversations, museum staff and strategic partners repeatedly cited three key reasons as to why museums in Northern Ireland had at that point shown little interest in developing a more holistic approach to digital engagement with visitors. The reasons were a lack of money, staff, and skills.

This context became the foundation for our action research project, which sought to develop a pedagogical approach that would facilitate critical praxis, influence change within the sector and help us to develop more confident and critically engaged students. The project was led by myself and Alan Hook, Lecturer in Interactive Media Arts, University of Ulster, and was undertaken as part of the university’s MA in Cultural Heritage and Museum Studies. It was delivered through two event formats – the first a three-hour digital crash course, and the second a twelve-hour hack day – and formed part of the existing ‘Cultures of Curatorship’ module. What follows is an account of these events, which is deliberately detailed to allow for replication and use by other academics but also links to the wider argument about what critical praxis could be like within the museum studies disciplines.

Digital crash course

The three-hour crash course started with a one-hour lecture on digital practice in museums, which introduced examples of best practice in social media, digital engagement and linked data, and provided students with contextual benchmarks. After the lecture students broke into small groups and were tasked with developing creative solutions to a number of ‘design challenges’, including:

The Ulster Museum would like visitors to engage on social media platforms and to visit the museum’s website as a follow up to their tangible visit.

The museum would like to develop an intervention in the entrance to encourage people to engage with them online.

The museum wants visitors to be excited by what they offer online. What could the museum do to encourage visitors to engage with them online?

At the start of the activity students were intimidated by the large sheets of blank paper and hesitant to note down ideas, ‘in case they weren’t right’. Writing down new ideas and challenging established practices was something many in the group had never done before. It was interesting that students got involved in heated debates about new ideas and approaches to responding to the design challenges, but found it difficult to translate conversations onto paper. It was thought that if they put their ideas on paper they would become ‘official’ and that this was more difficult than simply pitching ideas in conversation. To start groups off a number of ideas were added to their sheets of paper and this encouraged each group to add to what had been started, which seemed more attainable than starting on a blank page. By the end of the crash course there was real energy and students began to see that they already had a range of digital literacy skills from their personal lives that could be transferred into ‘professional’ digital literacy in a museum context.

Hack day at Ulster Museum

Elise Dubuc examines the purpose of museum studies in her 2011 article ‘Museum and University Mutations: The Relationship Between Museum Practices and Museum Studies in the Era of Interdisciplinarity, Professionalisation, Globalisation and New Technologies’.20 In this article she poses the question: are we teaching in order to reproduce the status quo, or in order to effect change? This provocation reminds us that if we want museum studies to become a critical praxis then it needs to extend beyond the walls of the university and actively ‘do something’ in a museum context.21 The idea that museum studies as a discipline should ‘do something’ provided the hypothesis behind the second part of this action research project, a hack day at the Ulster Museum, with participants drawn from the MA in Cultural Heritage and Museum Studies and also the BA in Interactive Media Art.

In terms of what ‘doing something’ looked like, we decided against asking students to pitch their hacks to museum staff because we felt that it would put unnecessary pressure on students who were seeking opportunities to impress and stand out in front of museum professionals. As such, while this event took place inside the museum it was not a formal partnership with expected, deliverable outcomes. This presented a challenge because by not working with the museum our ability to influence direct change was limited. However, the approach that we took created the opportunity for us to inspire students to become what theorist Jay David Bolter refers to as a hybrid, new media critic who ‘wants to make something, but what she wants to make will lead her viewers or readers to reevaluate their formal and cultural assumptions’.22

The hack day began with a short ice-breaker session, after which participants were split into teams of four, each of which included students from both the undergraduate Interactive Media Arts course and the postgraduate Cultural Heritage and Museum Studies course. During the morning we held two short sessions: the first, led by Alan Hook, looked at the concept of play and game mechanics, while the second session, led by myself, explored participatory design in museums. Each group was tasked with creating interactive experiences that questioned the notion of play in the museum. The task was deliberately loose; rather than telling the students what we wanted them to create, we encouraged them to show us what was possible. The only required outcome was a project blog (on Tumblr), which had to outline their team’s hack, and any prototype media they had produced during the event. With this approach we sought to empower students to think like practitioners, and seek to improve rather than replicate existing professional practices that exist in museums.

Each team responded to their brief in a different way, but across each one we noticed a disciplinary distinction. Those from a museums background were concerned with facts and accuracy, while those with advanced digital skills wanted to ideate – the more ideas and the crazier they were the better. Some teams revelled in the challenge to find a common ground, while others found this more difficult. A key challenge during the event was fostering positive team dynamics and negotiating compromises. One group argued for an hour about factual accuracy and which one of their initial ideas would be best to prototype; we intervened and explained that as emerging museum professionals they will have to work with designers, and as designers they will have to work with clients. This example demonstrated the need for emerging museum professionals to work outside their own discipline, as this provides opportunities to develop professional skills. It also provided students with the opportunity to discuss digital culture, changing media production trends, and how this was creating a new operating environment for museums. This conversation centred on critical praxis, and empowered students to develop new modes of practice.

Indeed, this clashing of perspectives demonstrates the differing theoretical perspectives which students on a range of courses come from before they even begin to explore how theory meets practice in a professional context. As such we need to consider how critical praxis can help students to navigate theoretical and discipline-specific language, theory and practice.

Organisational theorist Georges Romme has proposed three ‘archetypal modes’ of research: science, humanities, and design. He suggests that ‘scholars adopting the humanities mode intend to portray, understand and critically reflect on the human experience of actors inside social practices … all knowledge arises from what actors think and say about the world’.23 In essence, this academic approach, which we could describe as museum studies research within MacLeod’s model, would focus solely on empathising and defining a situation, but would stop short of taking action. The science mode, for Romme, is concerned with finding and explaining trends, while the design mode ‘focuses on producing systems that do not exist – either by changing existing social practices and situations into desired ones or by creating new practices from scratch’.24 We saw the archetypal modes of research as defined by Romme emerge within the teams on the day, and the challenges of interdisciplinary research and practice became evident very quickly.

One team created a particularly strong, and functioning prototype: a QR code video ghost tour of the museum. The video prototype featured Takabuti, a female Egyptian mummy played by a male participant who dressed himself up in fabric rags. Some participants took issue with the factual inaccuracies while others in their group were able to confidently explain the term ‘proof of concept’ and ‘rapid prototype’ to their teammates. Another group defined the ‘no photography policy’ as a challenge for them as young creatives. This team chose to work around the no photography rule and create an alternative audio tour of the museum as a means of demonstrating how museums can work with, rather than prohibit creatives. The group negotiated this rule by taking wide-angle gallery images for their blog, with their rationale being that copyright would not be infringed as the paintings would not be the main feature in their photographs. This group also produced a viable prototype – a 1960s era radio show – which featured music and news from the decade, and also made reference to objects that featured in paintings on display in the museum. The group explained:

The project started off from the generic idea that art can be intimidating for some visitors and that ice-breaking activities could encourage a more relaxed engagement with art. It also developed as an alternative to the traditional descriptive and self-contained audio tour format. The theme of the exhibition, stressing the sixties as a decade of revolt and innovation, spurred us to challenge the conventions of visiting museums and engaging with art … The period is certainly best remembered for its music. We used it as an entry point into the gallery as visitors are likely to relate to it in some way or other. The use of music is relevant from a learning point of view as it helps recreate the atmosphere of the time and of the creative process. It is also likely to trigger memories or emotions with visitors, hopefully encouraging deeper interaction and a few boogie steps.25

The simplicity of concept and materials for this project was striking. It is the type of playful interaction that could be thought up, prototyped and implemented in one afternoon. It is important to note at this juncture that participants in this hack day wanted to use platforms they were familiar with; for example, no one suggested creating alternative interpretation panels. Instead participants used platforms such as YouTube, Tumblr, Vimeo, Facebook and Soundcloud. This demonstrates that leading with a challenge, rather than a brief with a predefined outcome, encourages students to think beyond existing practice, and allows them to bring new platforms, languages and ways of working to the table.

Participants wanted to use contemporary culture as an underlying narrative to the digitally mediated responses they created. They wanted to relate the museum to themselves and to the world around them; they did not care about policy, instead they wanted to make people laugh, stop, stare and question. While it is right for museums to uphold accuracy as the cornerstone of museum practice, the emergence of visitor appropriation of collections is becoming endemic.26 Working with young museum professionals and digitally engaged visitors provides museums with a valuable opportunity to respond to this emerging trend.27 The relationship between hacks and established museum practices is something that teams reflected on when presenting their hacks to each other.

As with all hack days, the dialogue and debate that took place was more valuable than the project outcomes themselves. Participants gained valuable professional skills, and the interdisciplinary nature of this project replicates more accurately the nature of the museum workplace than a classroom ever could, and is an example of the shared practice-based methodology advocated by Lehmann and Werner.28 Emerging museum professionals are often bursting with ideas and enthusiasm. They bring with them fresh, culturally relevant insight that can side-step museum bureaucracy, dismantle a problem and find a solution. In short, they can balance theory and practice, and negotiate a pathway between the two.

2: Responding to design challenges at the Wellcome Collection

In October 2015 students on the MA in Visual Arts Management and Curating at Richmond University participated in a digital workshop at the Wellcome Collection, a workshop that was jointly led by myself, Danny Birchall, then Digital Manager and Russell Dornan, then Web Editor. This three-hour workshop sought to introduce the concept of digital practice in museums to students for the first time, but also to get them to think critically and practically about the role of managing and creating digital products in a museum environment. The workshop also aimed to refine and combine the fifteen hours of contact time delivered earlier in Ulster into a smaller scale model of critical praxis. The initial case study represented a significant body of work, but for critical praxis to become a successful and inherent approach to museum studies teaching, research and practice, then a more streamlined, lighter touch and less resource-intensive method is required. As such this second action research case study sought to examine how critical praxis could be enacted through one single taught session.

A key difference was that this workshop was delivered entirely in a museum environment (rather than a classroom or university environment), and in partnership with museum staff. In terms of refining the Ulster project into a shorter but equally effective method of enacting critical praxis, I turned to existing research on design thinking.

Design thinking as a model for critical praxis

‘Design thinking’ refers to the use of design principles to solve problems, an approach that is long established within design circles. It has more recently been brought to wider use as a framework for problem solving in areas such as business, service design, education and healthcare. Tim Brown, a proponent of design thinking and President and CEO of IDEO, an award-winning global design firm, describes it as ‘a human-centred approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success’.29 The term was popularised by the 1991 book Design Thinking by Paul Rowe, in which the author explored the use of design thinking within architecture.30 Since this publication, design thinking, according to Tilmann Lindberg, has emerged into a ‘meta-discipline’. By way of an example, Lindberg cites the emergence of new courses and schools devoted to teaching design thinking to non-designers in both America and Europe.31 Design thinking started out as ‘an open concept to describe a designer’s cognitive strategies of problem solving’ and has now become more formalised.32 Lindberg outlines three steps that are common across the numerous approaches to design thinking, namely illumination of the problem space, illumination of the solution space, and iterative alignment of spaces.33

This triple matrix of problem, solution and refinement takes as its central premise that nothing is ever finished. When a solution to the initial problem has been found, that solution can, through testing, always be refined. This premise forms the thinking behind the highly shared ‘Done Manifesto’. Developed by Bre Pettis, CEO of MakerBot, a company which produces 3D printers, the Done Manifesto challenges us to move away from perfection, or more accurately to ‘Laugh at perfection. It’s boring and keeps you from being done’.34 Perfection, and the development of finished products (be they academic papers or exhibitions) is something that academics and museum professionals are often trained to pursue. Design thinking, however, challenges us to work within the parameters of what museum researcher Nina Simon calls ‘perpetual beta’.35 Nothing is ever finished, and everything can always be refined.

Recognising that design thinking can ‘be seen as a grounding framework for multidisciplinary teams to communicate and to coordinate activity’, digital theorists Paul Gestwicki and Brian McNely have examined a number of design thinking frameworks with a view to identifying one suitable for use within museums.36 Specifically, their research looks at how design thinking principles can aide the development of educational museum games, and explore how design thinking principles could provide a model that museum professionals could use to depart from their pursuit of perfection. Gestwicki and McNely acknowledge the work of Karl Aspelund, Tim Brown, and Soren Boulvig Poulsen and Ulla Thorgersen in developing useful models of design thinking.37 While each of these cited authors present models of varying degrees of complexity, they all display the three common areas identified by Lindberg: problem, solution and prototype. However, Gestwicki and McNely set apart the work of George Kembel as being particularly useful within the context of museums because his model places a strong emphasis on empathy.38

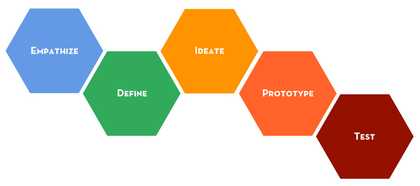

Fig.2

The design thinking process used at the Stanford d.school

Reproduced in Dana Mitroff Silvers, Maryanna Rogers and Molly Wilson, ‘Design Thinking for Visitor Engagement: Tackling One Museum’s Big Challenge through Human-Centered Design’, MW2013: Museums and the Web 2013, 2013

Kembel, co-founder and Executive Director of the Stanford d.school, developed the design thinking process illustrated above (fig.2). The inclusion of traditional humanities approaches such as ‘empathy’ and ‘definition’, alongside the more innovative and activist stages of ‘ideation’, ‘prototyping’ and ‘testing’, make it a useful model for ‘risky’ research within the traditional parameters of museum studies. Dana Mitroff Silvers, Maryanna Rogers and Molly Wilson used what is commonly known as the Stanford d.school Design Thinking Process to develop visitor engagement within museums.39 While Kembel developed the model, it is more widely attributed to Stanford d.school than its author. Mitroff Silvers, Rogers and Wilson, a team of researchers at Stanford d.school and members of staff at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA), developed a collaborative project to provide graduate students with opportunities to develop human-centred design skills in a real-world context. Through a three-week intensive format, students from across Stanford were invited to take part in a programme of workshops that concluded with students presenting visitor engagement solutions to SFMoMA. The design thinking process provides an intensive, loose and supportive format to facilitate interdisciplinary practice, and as such participants ranged from law students to medical students. The process supports risk through, for example, the ideation stage, which invites participants to develop the broadest range of ideas, regardless of how viable they may seem on paper. This challenges participants to think beyond what is right and wrong, and challenge established social practices that exist in everyday spaces (in this instance museums). For the team of researchers, the strength of this process is its ability to tackle ‘messy real-world challenges that are hard to define and even harder to solve’ in a quick and low-budget fashion.40 By embracing perpetual beta, this process permits participants to prototype, test and refine, rather than being paralysed by the pursuit of perfection.

The human-centred focus within both these projects (Getswicki and McNely and Mitroff Silvers, Rogers and Wilson) is that of the visitor. However, in my research the human-centred focus is on museum professionals. ‘Design thinking is a philosophy, a mindset, and a methodology’ and thus the flexibility of this process means that it can be used in different contexts, sectors, and with different actors and protagonists.41

Adopting design thinking for museum studies

The Stanford d. School Design Thinking Process provides a linear narrative with which to stretch the boundaries of established museum studies research practices. Using this framework this research project straddles the boundaries of humanities and design modes of research as defined by Romme.42

The workshop began with a series of presentations exploring digital practices in museums, and more specifically the digital strategy of the Wellcome Collection. Danny Birchall then introduced the concept of project constraints and design thinking methodologies through a paper prototype. The linking of problems to prototype and proof of concept solutions demonstrated how ideas could be translated into action research in a low-budget, time-constrained manner. It also demonstrated that critical praxis is a way of working, that requires confidence more than it does resources. Students were then presented with four design challenges – real problems that the digital team at the Wellcome Collection were currently working on – and tasked with prototyping solutions to those problems. The challenges focused on deepening relationships with visitors, collecting experiences, making galleries playful and reaching international audiences. Each statement provided an empathic or contextual background, followed by a defined challenge statement or question, for example:

We would like visitors to see visiting the Wellcome Collection as the start of a bigger and deeper experience, involving a relationship between us and the visitor. We don’t just want to tell people to visit a website or follow a hashtag, we want to offer something meaningful to the visitor, based on our digital capabilities.

What could we do to make a visit to the Wellcome Collection the beginning of a relationship that is supported by digital media?

Students self-selected which challenge they wanted to respond to and formed groups based on these challenges. Each group was given thirty minutes to develop a solutions concept, on which they received feedback, and were provided with fifteen prototype development prompts. A checklist that encouraged students to think about the practical development and application of their concepts included:

- Where does the experience begin? (i.e. in a specific gallery, the lift, the toilets, at the ticket desk, on the museum’s website, via Twitter, Facebook etc.)

- How does the experience begin? (you climb through a tunnel, you open a secret door, you click an online link, you open a text message)

- Describe the experience in detail (the key information a museum would need to develop or implement your concept. Consider music, lighting, use of technology, costumes, number of participants, how the experience is facilitated, i.e. is it self-directed or lead by a guide, is it a static experience, or is it mobile?)

- How does the experience end? (Are there one or multiple possible conclusions?)

- How long does the experience last? (Are there multiple experience entry and exit points? Is there an online, or mobile follow up to the in-gallery experience?)

This check-list encouraged students to question existing museum practice and begin to think about new ways museums could work, produce and curate. Students then spent sixty minutes in the gallery spaces, taking photographs and working on prototypes. While the outputs from this workshop were much more paper-based than the twelve-hour hack day in Ulster, this shorter format provided students with the opportunity to critically reflect on theory, respond to challenges and prototype solutions.

Conclusion

The design thinking process developed by the Stanford d.School provides a useful model for linking traditional approaches to museum studies research with the more activist model proposed in this paper. The process takes as its starting point two modes of traditional academic enquiry: empathy and definition. The design thinking process neatly patches the humanities and design modes of research together; on the one hand it is concerned with identifying and defining social practices through empathy, and on the other it is interested in designing new social practices. The partnering of a traditional humanities approach with a more innovative design approach creates a rigorous model of museum studies as a critical praxis within the accepted parameters of academia. Such an approach uses established practices as a solid foundation from which a more innovative and ground-breaking departure can be taken.

Central to the critical praxis theoretical framework and design thinking methodology proposed in this article is the use of challenges rather than a set brief, a problem statement rather than a defined task. If we want museums to be innovative, responsive and progressive institutions then we need to develop pedagogic practices that support risk. This paper presents evidence to support one model for engendering critical praxis within existing museum studies courses; however, more research is needed into how museums studies as a discipline can produce emerging professionals who are robust, agile and innovative. We need to look towards a pedagogy that blends operational and critical skills and encourages reflective practice. A shift towards critical praxis may be the practice-based methodology that museum studies as a discipline needs to strengthen and sustain itself in the twenty-first century.