Kenneth Armitage was a sculptor of the human body. For over fifty years he used his prodigious sculptural imagination to make figurative work that had ‘an instinctive concern with a human condition or attitude’.1 It was an ambition shared by many artists of his generation and one that was given considerable critical support in the early part of his career.

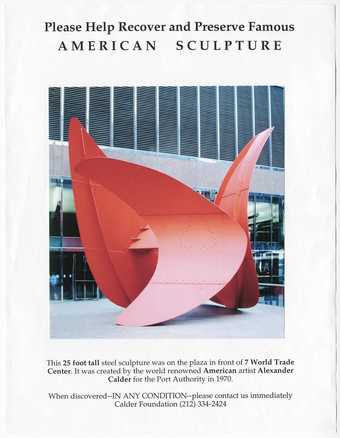

This article, however, is not about the triumphant years of the 1950s, but about a work made at the beginning of what was to be Armitage’s difficult mid-career, that is to say the early 1960s when he was in his mid to late forties. These were pivotal years in the development of sculpture in Britain. It was a time when the so-called ‘New Generation’ artists were challenging some of the fundamental assumptions about what sculpture might be – not simply what it was made from or might look like, but the humanist ideas that had dominated western sculpture for much of its history. They were also the years in which Armitage developed a new type of sculptural expression, one which was increasingly abstract in form but loyal to the humanist principles of his earlier works. For a number of influential critics his allegiance to these principles cut his work adrift from the prevailing current of high formalism and made it, and much else besides, old fashioned. While artists with the sort of solid international following of Henry Moore thrived despite such criticisms, for those like Armitage, whose reputations were more fragile, they were disastrous. By 1967 critical support had ebbed away to such an extent that he was by his own admission ‘just an old name’, to which observation he added ‘few really care about my work anymore & I don’t blame them’.2

His isolation from high art’s circles of influence did not prevent him, however, from winning a number of public sculpture commissions around the world, and it was as a public sculptor and teacher that he made a living for the next thirty years or so. It was only in the 1990s that his standing as an important British artist of the post-war era began to recover. This resurgence of interest coincided with a wider reappraisal of post-war British art and the rise of such contemporary artists as Antony Gormley, whose work continued the humanist tradition of sculpture.

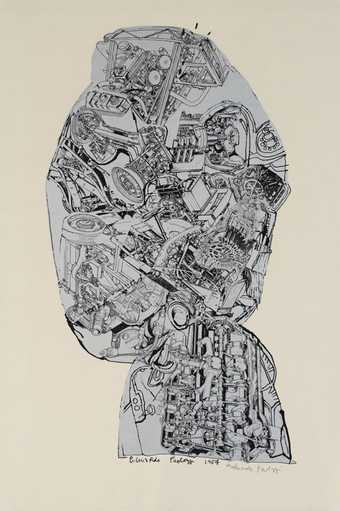

While this essay concentrates on just one work, Pandarus (version 8) (fig.1), the underlying argument is that for all the contemporaneous claims that Armitage’s work of the 1960s was irrelevant to the order of high formalism promulgated by the New Generation, it was nonetheless far more attuned to significant social developments of the period than has been accorded to it. It is perhaps this that accounts for his survival as a public artist and his current appeal to a modern audience.

Kenneth Armitage

Pandarus (Version 8) (1963)

Tate

Pandarus (version 8): the object and its manufacture

The Pandarus series consists of twelve sculptures made between 1962 and 1965. All share the same loosely figurative motif of a vertical column or slab surmounted and sometimes penetrated by hollow, conical funnels. They are also all made from bronze or its close cousin brass. What distinguishes them from each other are their obvious formal variations within the motif and a considerable variety of scale – some being no more than a few inches high, and others about the average height of a person.

Pandarus (version 8) measures about five feet ten inches high and was cast in brass in the second half of 1963. It is an irregular, ellipsoid column divided into sections by three ridged bands. These bands, which overlap the section below as if each were stacked, or were the edge of some surface skin rolled down, go right around the column. The top and the bottom bands are roughly horizontal, while the middle one slopes at a slight angle. In the top section two large funnels penetrate all the way through the column and stick out the other side. The left hand funnel as we look at it is the larger and more open, and is oriented on a vertical axis, while the other is a more or less horizontal ellipse. When seen close up they present a clear view through to the other side of the sculpture. From a distance, however, their internal shadows give them the appearance of dark, open mouths, or ears, or sockets which create a striking contrast to the closed form and shiny surface of the main column. In the middle section there is a deeply incised horizontal slot, which in its shape and position inescapably resembles a human navel. Like the funnels, it is veiled in deep shadows as if it were the entrance to the interior void of the sculpture. Beneath this is the narrowest section, which serves to break up the regular division of the column and adds complexity to its visual rhythm. This essentially graphic method of syncopating a simple shape is complemented by the slight outward spread of the bottom section. Like the splayed bases of other Pandarus sculptures, the broadening out of the column gives it a look of structural stability, rather like the base of a tree.

The surface is textured with a myriad of small marks and around the navel deeply incised lines cut into the skin of the object forming a dense, intricate pattern. Elsewhere traces of metalworking are also evident, especially around the funnels, the rims of which have been scratched with files. More noticeable still are the welding joins at the intersection of the funnels with the column; these have not been chased and stand proud of the surface like welts. These irregularities are blended into a visual whole by the patina, which is a warm brown colour.

Armitage intended to make up to three casts of this sculpture, but it is likely that only two were made, both by Fiorini & Carney Ltd in 1963.3 This contradicts Armitage’s later statement that all the Pandarus sculptures were unique.4 In fact, when six of them were exhibited in 1963, only Pandarus (version 1) was listed as unique, and the rest were advertised as being in editions of six.5 In 1965 when the complete series of twelve, including Pandarus (version 8), was shown at Marlborough Fine Art, only Pandarus (version 5) was listed as unique.6 The apparent discrepancy between Armitage’s statement and these published edition sizes can be accounted for by the fact that in most cases only one of each was ever cast, probably because there was no further demand. Most of the works listed as being in an edition of six in 1963 were already shown as being in smaller editions in 1965.

There is similar confusion over the material used. In 1963 all of the six exhibited works were listed as being in bronze. Two years later one of them was described as being aluminium (and a different height), and the rest as brass. Pandarus (version 8), which had not been exhibited in 1963, was also listed as brass. Such inconsistencies are not particularly unusual. In fact, while it is fairly rare for a modern sculptor to use brass, the material differences between brass and bronze are minor. Both are copper alloys, brass being a mix of copper and zinc, while bronze is of copper and tin, with a comparatively high copper content. Although brass does have some distinctive casting properties, it is not apparent that Armitage took much advantage of these. What does seem to have been of interest to him, however, was the yellow colour of brass, which gave the patina some of its warmth.7 The relative cheapness of brass may also have influenced his choice of metal.

Likewise Armitage’s casting procedure was also faintly unorthodox. The surface intricacies of Pandarus (version 8) meant that the ‘lost wax’ technique was the most suitable way of casting it. Lost wax is a complicated and highly skilled process, and one that most artists are inclined to delegate to experts. Armitage, however, made his own wax replicas from his original model, using his own plaster-piece moulds. The sculpture was then cast in separate pieces, the four sections of the column and the two funnels, by Fiorini & Carney. Armitage carried out much of the preliminary work in his large studio near Olympia in London, but it is not known whether he or the foundry brazed the various parts together and patinated the sculpture.

Kenneth Armitage’s biography

Armitage was born in Leeds in 1916. His father worked for an oil refinery and his mother looked after the three children, of whom Armitage was the youngest. The death of the middle child, Norah, led to his mother’s conversion to Christian Science; a doctrine that she followed strictly and applied to her children. Apart from instilling in Armitage a life-long fear of all illness and a sceptical view of the beneficence of God, his mother’s unbending beliefs doubtless contributed to his sense of being stifled by conventions. By contrast, his warm accounts of the carefree atmosphere of his uncle’s home in Ireland, where he spent summer holidays, suggest that this was the model he sought for his own life.

Relations between Armitage and his mother were made more difficult by his obvious aptitude for art. In 1934, against her wishes, he enrolled at the Leeds College of Art. He left Leeds in 1937 and went to study sculpture at the Slade School in London, from where he graduated in the summer of 1939. A few months later the Second World War broke out and he volunteered for the Royal Artillery. Despite a battery commander’s report in which he was described as ‘Eccentric, untidy and should be curbed’,8 the value of Armitage’s extreme visual acuity was appreciated by his superiors and for most of the next six years he taught aircraft and tank identification at Deepcut.

In 1940 he married Joan Moore, whom he had known at the Slade. She was nine years older than him and was also a sculptor. It was to be a complicated marriage founded on mutual admiration but little physical attraction. To a certain extent, Armitage’s sense of sexual frustration, which was a constant source of anguish, found expression in his work, as we shall see later. The marriage floundered shortly after the war and by the mid 1950s they had separated, but they never divorced. In fact, they remained close friends throughout their lives and kept up a regular and frank correspondence.

On demobilisation in 1946 he was appointed Head of Sculpture at the Bath Academy of Art which had recently moved to Corsham Court in Corsham, Wiltshire. It was there, among a group of colleagues that included William Scott and Peter Lanyon that he made his first original work. His decision to give up carving was crucial to this development. Like many art students in the 1930s, Armitage had been taught carving as part of his basic training. Its inclusion on sculpture courses marked a remarkable turn around in the appreciation of carving, which up to the 1930s had largely been ignored by the teaching academies. In Britain before the First World War Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Eric Gill, and Jacob Epstein had pioneered a new interest in it as a high art discipline and had been supported after the war by a rising generation that included, among others, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and A.H. Gerrard, who was Armitage’s tutor at the Slade. Yet for all the enthusiasm with which these artists had taken up carving as liberation from the tradition of modelling and casting, for Armitage’s generation, for whom it was part of the curriculum, it had none of that transgressive excitement. In fact, Armitage, for one, found the structural limitations of wood and stone a significant impediment to formal innovation. After 1946, therefore, he worked only as a modeller, making maquettes in plaster or clay and then casting them in metal, usually bronze.

The tensile qualities of metal allowed him to make more linear, delicate shapes than stone or wood permitted, and he soon made use of this in his sculptural representations of the body. These works displayed an aesthetic of flattened mass that incorporated linear detail. By 1950 he was making such sculptures as People in the Wind, 1950 (fig.2), in which a figure or group of figures are shown in movement and are melded into a single thin slab or membrane of bronze, their heads and limbs reduced to small, indistinct blobs and rods.

Kenneth Armitage

People in the Wind (1950)

Tate

Armitage was mystified by the source of these shapes and later suggested that they may have come from his subconscious memory of looking at the outlines of aircraft and tanks during the war. Certainly some of the membranes bear a resemblance to wing profiles and some of the protruding arms look a bit like tank barrels. But whatever the origins of these merged forms, other aspects of the work had more easily identified precedents. Since his days at the Slade he had adapted the formal ideas of archaic sculptures for his own work. This is particularly striking in such bronzes as Moon Figure 1948, a single figure with a crescent head, flat torso and crossed arms, which owe much to the abstracted, frontal figures of Cycladic sculpture. Likewise the formal source for the flattened bodies, pinheads and small breasts that were to characterise his work throughout the 1950s may have been partly derived from ancient clay statues found at Philistine Ashdod in the Middle East.

Such interests were not unusual by the mid twentieth century. Collections of ancient and tribal works had provided source material for many artists before the war, not least Picasso, Moore and Epstein, and continued to do so after. On the whole this was an interest in the formal inventiveness of such works, and was often supplemented by romantic notions about the ‘authenticity’ of the societies in which they had been made. The most significant post-war manifestation in Britain of this primitivising narrative was the Institute of Contemporary Arts’s 1948 exhibition 40,000 Year of Modern Art, which brought together a number of ancient, ethnographic and contemporary works to reveal ‘a universal language of forms’. In his preface to the exhibition, Herbert Read suggested that the abstraction or the distortion of natural form common to all the works spoke of ‘a vague sense of insecurity, a cosmic anguish’.9 Although Armitage visited the exhibition, it is hard to know how far his interest followed Read’s. What is certain, however, is that, like his colleague and friend William Scott, he perceived a formal and sensual vitality in such objects and sought to instil similar qualities in his own work.

In 1952, after six years at Corsham, Armitage’s professional career started to take off. It began with the Young Sculptors exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, where his work was displayed alongside that of Robert Adams, Reg Butler, Geoffrey Clarke, Hubert Dalwood, Elisabeth Frink, Bernard Meadows, Eduardo Paolozzi and William Turnbull, among others. This was the first time his work had been shown in a major gallery. It was followed in May by the British Council’s exhibition at the Venice Biennale, which included a group of contemporary British sculpture that Philip Hendy and Herbert Read had helped select. Armitage was shown with Adams, Butler, Lynn Chadwick, Clarke, Meadows, Paolozzi, Turnbull and Moore. Although Moore and, to a lesser extent, Barbara Hepworth had established an international audience for British sculpture after the war, few could have expected the extraordinary enthusiasm with which this younger generation was greeted at Venice. In many ways it ignited all their careers. Even before Armitage returned from Italy that summer, Alfred Barr, the director of MoMA in New York, had visited his London studio to buy two bronzes for the museum. Over the next seven years or so, art institutions and private collectors acquired his work at a considerable rate. The pinnacle of this success came around 1958, when he again represented Britain at the Venice Biennale, but this time with a one-man retrospective display.

While the 1952 exhibitions brought Armitage to a wide audience, they also provided an intellectual framework by which to understand it. Faced with Armitage’s ‘dramatic contrasts between flat stretched surfaces casting wide shadows and spiky protuberances thrusting into the light’, Sir Philip Hendy asked in his review of Young Sculptors ‘when such virtually abstract phenomena are translated into semi-human beings … can these express more than a generalised despair? Is there no more to express these days?’10

This theme was developed a month later by Herbert Read in his catalogue essay for the Venice Biennale exhibition. Entitled ‘New Aspects of British Sculpture’, it is the source of the phrase ‘Geometry of Fear’ and has become a defining text on post-war British sculpture. In it Read explained that Moore had been included to suggest some continuity between the new generation and an older one that included Calder, Giacometti and Picasso, as well as Moore, but without implying a dependence. For Read the fundamental difference between the two generations was the climate of violence and despair that had settled on life since 1914. Read had served in the Great War, and was a poet and a pacifist, with a sense of a fundamental moral responsibility. He argued that the younger artists, all born between 1913 and 1924, had no memory of a world where peace had prevailed. Thus their work, which he described as the ‘Geometry of Fear’, revealed ‘the iconography of despair, or of defiance’,11 not simply because of the recent history of the Second World War or the present reality of the Cold War, but because they had been brought up in a culture of war. This manifested itself in an anti-monumental and linear aesthetic that was ‘close to the nerves, nervous, wiry’.12

Turning specifically to Armitage, Read described his melded figures as ‘diaphragms of agony’ and considered them to be ‘a sardonic commentary on the stretched agony of human relationships’.13 Six years later Read returned to the subject in his catalogue essay for the Armitage display at the 1958 Venice Biennale. He identified the imperfections and informality of the sculptures as ways of conveying ‘vitality’. This idea of vitality was rooted, he suggested, in the realisation that, ‘Life is not tidy; it is a tremor in the mud, a swelling in the flesh, an obscure nausea, a mucous ectoplasm flowing over the rigid structure of matter.’14 He went on to ask why an artist might want to depart from the classical ideal in this way, and found the answer in Sartrean existentialism. While he acknowledged that Armitage did not subscribe to Sartre, he nonetheless concluded that ‘he does share the same raft in the dissolving substance of our civilisation, and being a man of sensibility, and a plastic artist, seeks to express his anguish in the same significant images.’15 This reading of Armitage’s sculpture was restated a year later in the New Images of Man exhibition, a group show held at MoMA in New York. Peter Selz’s catalogue essay presented the collected works as an expression of the anxiety and solitude of a generation steeped in the barbarity of mankind. Quoting Kafka’s Metamorphosis, Selz described Armitage’s figures as ‘helpless bugs; “…they signify nothing more than the absurdity of the body that the human spirit is condemned to occupy”.’16

However, for some contemporaneous critics the work was more ambiguous than the dominant existential interpretation suggested. Such sculptures as People in the Wind could equally be understood as being playful, even optimistic. For instance, in that work the figures are melded into a new organism, one in which the number of heads does not correspond to the number of limbs. This physical transformation of the individual could as easily be understood as a joyous affirmation of the group as a social phenomenon as it could a corollary for the ‘dissolving substance of our civilisation’. Such views were expounded by critics like Robert Melville, who, for example, thought the same works that Read had described as ‘diaphragms of agony’ possessed ‘a charm and lovableness which is rare in modern sculpture’.17 Such differences of opinion set a pattern for the critical reception of Armitage’s work. On one hand, art institutions incorporated it into a loosely existential narrative, while on the other, some independent voices discussed its uplifting human themes and formal qualities. The first major disruption of this pattern occurred in 1959, when the one-man retrospective from the Venice Biennale transferred to the Whitechapel Art Gallery. In a new catalogue essay, Alan Bowness considered the work to be urban in its sources and forms, and warmly human in content. To Bowness, Armitage’s 1950s figures were not angst-ridden. On the contrary, he felt that ‘their contented happiness as they quietly sit or stretch or roll over, feet and arms in the air’ was infectious, and he reassured the reader that ‘it is quite proper to smile before them’.18 His view revealed a far more positive understanding of the work and the world: one of faith in human abilities and in the community of man.

Pandarus (version 8): meaning

From the mid 1950s Armitage’s sculptures began to increase in mass and volume, and by the early 1960s the flattened forms of his previous work had been replaced by bodies reduced to little more than a truncated mass of bronze. The torso became a solid, rounded form. Short stumps replaced heads and arms, and legs were just spindly attachments to the torso. The emphasis on a central mass and the atrophy of arms made the work increasingly monolithic, giving it an ominous, even hieratic stillness. This was complemented a new portentousness in the titles. In place of the earlier preference for such mundane descriptions as People in the Wind or Figure Lying on its Side, more allusive titles began to appear, among them those with direct mythological associations, such as Sibyl and Prophet. It was at this point that Armitage embarked on the Pandarus series.

Even within Armitage’s extraordinary oeuvre the Pandarus monoliths with their sprouting mouths are remarkably strange looking. The totemic motif has precedents in the stelae and standing stones of ancient civilisations, which Armitage knew both through the British Museum collection and his travels and reading. Such primitivising references were consistent with the Cycladic forms found in his earlier work and resonated with the work of such contemporaries as William Turnbull. Yet, even these sources could not account for the funnels and the looping bands of such works as Pandarus (version 8). These were entirely new developments, and ones that critics struggled to understand.

The title of the work comes from the character Pandarus in the story of Troylus and Criseyde. The tale itself is perhaps most familiar to a modern audience through Shakespeare’s play Troilus and Cressida, but its origins lie in the Middle Ages. It was first chronicled in the twelfth century by Benoît de St. Maure, then revised and reworked by Boccaccio in the early fourteenth century, and again by Geoffrey Chaucer in the 1380s. In essence the story, which is set in the besieged city of Troy, recounts the secret and tragic love affair of Troylus, one of King Priam of Troy’s sons, and Criseyde, whose father, Calkas, has fled the city to join the Greeks. Their secret affair is conducted with the assistance of Pandarus, who is Troylus’s friend and Criseyde’s uncle. Shortly after they consummate their love the Wheel of Fortune turns against them. The traitor Calkas persuades the Greeks to offer one of their Trojan captives in exchange for his daughter Criseyde. The Trojans agree and Criseyde, who has vowed to be true to Troylus, is led out of the doomed city to the Greek encampment. But once there her affections soon turn to Diomede, a Greek warrior. When Troylus discovers that she has broken her vow, he launches himself into the battlefield, heedless of all danger.

In Chaucer’s poem Troylus is then killed by Achilles, whereas in Shakespeare’s he lives. This is just one of many differences between the poem and the play, but the fundamental distinction is philosophical. Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida reveals a cynical world, a place where the heroes of Greek mythology are merely political schemers, and in which there are no neat solutions or honourable motivations. In this world Pandarus is little more than a comical but cunning pimp. Chaucer’s poem, by contrast, is founded on the notion of a cosmic order determined by Fortune and is suffused with a warm and earthy humanity. At the poem’s heart is a disquisition on pre-destination which concludes that the omniscience and omnipotence of Fortune or God, the two become interchangeable, are absolute, and fate is irrefutable. Yet this assessment is only reached with the wisdom of hindsight at the end of the story; up to that point the issue is in the balance. Throughout Pandarus represents the counter proposal, that regardless of the existence of fate, aims are only achieved through direct action. It is, he says, pointless to languish in the passive acceptance of an unknown, perhaps non-existent, fate when it may be possible for people to control outcomes by their own actions.

It is as an advocate of this essentially humanist proposition that Pandarus acts as a go-between for the lovers. He serves as a means of persuasion and communication, encouraging Troylus and coaxing Criseyde, shuttling letters, organising assignations, and eventually arranging their sexual union. In these activities he is presented as a loveable if bawdy friend, and not as one of Shakespeare’s ‘Good traders in flesh’.

Armitage admired Chaucer’s work and read it regularly. In fact, in 1963, a year after he had made the first Pandarus, Edizione del Cinquale, an Italian publisher, invited him to illustrate a book of poems of his choice. He chose The Reeves Tale but later claimed that he would have asked for Troylus and Criseyde, his ‘favourite Chaucer of all’, if it had not been so long. In the same interview he commented that his Pandarus sculptures referred to Chaucer’s ‘noisy but kind’19 character.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Troylus and Criseyde is how current some of its attitudes appear to be to a modern liberal society. There is, for example, no suggestion that the sexual consummation of Troylus and Crisede’s love outside wedlock is shameful. On the contrary, the act is tenderly portrayed as a natural and joyous expression of human love:

Criseyde unloosed from care or thought of flight,

Having so great a cause to trust in him,

Made much of him with welcoming delight,

And, as the honeysuckle twists her slim

And scented tendrils over bole and limb

Of a tall tree, so, free of all alarms,

They wound and bound each other in their arms.

(Book III, verse 176)20

The obvious delight that they (and Pandarus) derive from sleeping together may well have resonated with Armitage, who in his letters to his estranged wife made much of the pleasure he derived from sex. But while he could make such remarks in his private correspondence, it was impossible in the 1950s to address the subject openly in his exhibited sculptures. The moral climate in post-war Britain was such that it was extremely difficult for artists to refer to sex except through an indirect, codified visual language or in drawings. William Scott, for instance, imbued his still lifes with hidden sexual meaning, while the erotic charge of Chadwick’s joined winged figures was deflected by the metamorphosis of the human figure into a bird. Equally, while it was difficult for artists to deal with sex in their work, it was more or less impossible for critics to discuss it. Hence while Armitage’s was able to write to his wife in 1951 and comment, ‘I look at my work & can see in it sexual frustration (as in yours) – my dual figures I’m sure are because of this’,21 no critic made a similar observation throughout the decade. Instead they were confined to the existential or cheerfully humanist interpretations.

By the early 1960s, however, the cultural climate had changed sufficiently that the subject could be addressed more directly. When Philip Larkin wrote that ‘Sexual intercourse began/In nineteen sixty-three’ he did so with some justification. Not only was it ‘Between the end of the Chatterley ban/And the Beatles’ first LP’, it was also about the time that the contraceptive Pill was beginning to be widely available. The shift in attitudes, though not as great as sometimes claimed, was nonetheless palpable. And in this context, Armitage’s open evocation of Pandarus is a manifestation and a celebration of the social liberalism that had begun to bloom in Britain.

The implications of the sculpture’s title are elaborated in its form. It is a large work with obvious erotic connotations. The vertical column has clear associations with a phallus, as do the funnels with orifices. Equally the manner in which the funnels are integrated into the column carries fairly straightforward sexual connotations. The top section of the column was cast with two holes in it, in to which the funnels were inserted and brazed. The welt marks caused by the brazing have created a surface disruption around the intersection that stresses the act of penetration. If this carries a latent eroticism, then the surface texturing is a yet more overt manifestation. Contrasted with the myriad of small blemishes that cover the piece, the deep cuts around the navel have a disturbingly visceral quality. If these marks are recognised as an index of the artist’s hand, then the delicate blemishes suggest a caressing, gentle touch and the incisions around the navel a violent frenzy.

Alongside this theme of eroticism is a related one of communication. Apart from their sexual associations the funnels also refer to Pandarus’s role as a go-between for the lovers. They allude to mouths and trumpets, while also being literally channels from one side of the column to the other. This theme of communication had been central to Armitage’s work since the Fifties. In many of his drawings and sculptures, a figure was shown in contact with others or reaching out to the viewer. In People in the Wind and other early works the positioning of the figures’ arms was the primary device for expressing this. Up to 1952 the vocabulary of these gestures was quite limited, but thereafter he directed them with a new confidence. The Italian sculptor Marino Marini, whom he met at the Venice Biennale, seems to have been the catalyst for this development. Although Armitage already knew of Marini’s work, the experience of seeing a lot his sculpture together and of meeting him seems to have fired Armitage with a new enthusiasm. Writing to his wife from Venice he declared, ‘there is only one sculptor exhibiting who is better than me – Marini. And he is superb. It makes me want to work.’22 Marini was supremely good at conveying emotion through human gesture. Often working within the confines of a repeated motif, for example, a man on a horse, he was able to express an extraordinary range of feelings by slightly changing the position of an arm or the angle of the head. Armitage incorporated this aspect of his work into his own sculptures, and over the next few years he developed a vocabulary of eloquent poses. In some sculptures, arms and legs burst outward in imploring gestures. In others, for example Seated Woman with Square Head (version B), 1955 (fig.3), the limbs remain integrated in the main slab and the figure appears self-contained, contemplative, and perhaps forlorn. The neutral titles offered little help in interpreting these gestures, and consequently they were seen by different critics to be either desperate, or ecstatic, or even playful. Whatever the ambiguities of these 1950s works, when considered with the suggestion of community and union in the fused groups, they seem in general to assert a human need for communication and physical comfort.

Kenneth Armitage

Seated Woman with Square Head (Version B) (1955)

Tate

Released from the moral strictures of the early post-war era and empowered by success, Armitage felt the need to experiment in the early 1960s and to move on from his earlier work. In so doing he made sculpture which addressed the underlying subjects of his 1950s work more directly, but in so doing he revealed a greater degree of ambivalence about them. Abstracted and strange, the alien appearance and austere totemic form of the Pandarus sculptures provoked a sense of hieratic menace for some critics. Bowness saw within them a darkening of mood, consistent with his understanding of Pandarus as ‘not a nice character’.23 Such readings are supported by the black and white photographs that Armitage chose for the 1996 monograph, which emphasised the dark internal shadows of the funnels and navel, with their suggestion of a mysterious interior world. Simultaneously, however, such devices as the human scale and prominent navel of Pandarus (version 8) deflate the hieratic associations of the monolith. Evidently there was none of the playfulness in this work that some critics had ascribed to his earlier sculptures, but nor was there a commensurate ascendance of existential themes. Instead Armitage, tempered by experience and liberated by circumstance, explored the physical nature of human relations with a new openness and profundity. Such works as Pandarus (version 8) advocate a world in which human physicality is not a shameful desire but a primal, urgent and above all acceptable need.

In a review of Armitage’s 1962 exhibition at the Rosenberg Gallery in New York, the American sculptor, Don Judd, attacked his work for being ‘obdurately stupid’ and imbued with ‘primordial idiocy’. For Judd, a pioneer of minimalism, Armitage’s humanist figuration was anathema. In Britain the advent of Anthony Caro’s colourful, abstract sculptures heralded the passing of the Geometry of Fear era. In 1965, the year in which the ‘New Generation’ sculptors came to prominence, Robert Melville wrote in his review of Armitage’s Marlborough Fine Art exhibition ‘The area between the effigy and the pure abstract, where twentieth-century sculpture had so many of its triumphs in the past, has turned into a dust bowl. No one can make biomorphs, organic abstracts and invented personages look right any more. The spirit has deserted them’.24

In truth, the spirit had not left the sculptures, but the will to believe in it had left such critics as Melville. The dilemma for Armitage was that just when the broad cultural climate had turned in his favour and he was able to express openly his ideas about human sexuality and relations, vanguard art was heading towards a type of abstraction that seemed to eschew any direct comment on such matters.

In one particularly despondent letter to his wife in 1967, Armitage recounted a conversation he had recently had during which his companion told him ‘Armitage you’re in a rut. Years ago you were right in the swim like the new ones are now, but now the wheel of events has turned right away and you are left working now pointlessly for some private reason about which nobody cares anyway. You ought to do something else.’ What is remarkable about this letter is the painful honesty with which Armitage assessed the truth of this comment and the inner resilience that led him to conclude, ‘Perhaps everybody is right and I’m just conceited and thick-headed and vain thinking I’ve the right to pretend to be doing something. One thing I do know, however, is that while my work in the past never change [sic] anything or made people think it did give many people quite a bit of pleasure – they liked it for reasons – perhaps warmth – I don’t know.’25

In retrospect, that assessment rings true. For the rest of his career Armitage continued to elaborate, often against the grain of critical opinion, his humanist explorations of the figure, and often most successfully and appropriately through public sculptures.