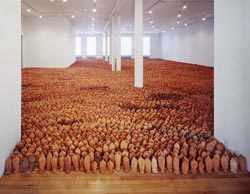

When Antony Gormley proposed that a local community make Field for the British Isles for his exhibitions in Liverpool and Dublin, it seemed a rare and exciting opportunity. It was also a natural development of the way in which Tate Liverpool works with its local communities.

In order to make Field for the British Isles, an estimated 30 tonnes of clay was needed. Ibstock, a St Helens brickmaking company, were approached and asked to provide the clay. They had never before had such a request, but showed imagination in generously offering to provide not only the clay, but also the use of their kilns and expertise.

Once the raw materials had been identified, the human labour and creative energy to make around 40,000 figures was necessary. We looked to the community who live in the area around the Ibstock factory, and contacted families through two local schools, Sutton Community High and Sherdley County Primary. From the beginning Antony had stressed that an important dimension to the making of Field was that children, parents and grandparents work together, side by side.

The two head teachers took a leap of faith and gave their immediate support to the idea. Letters were sent to parents and a date arranged for those interested to meet with Antony to find out what was involved. In the meantime the logistics of the project had to be considered - finding a suitable venue in which to work, matters of safety and security and, not least, feeding the group!

When Antony came to Merseyside in July 1993, Sutton Community High School's Robins Lane annexe has been chosen as a venue for making the work. At a lunchtime meeting, Antony talked in detail about the ideas behind Field and his experience of making it in other parts of the world. We discussed the real human commitment the project required. At the end of the meeting, Antony asked for a show of hands. Everyone present offered themselves, and from that group others followed.

Field for the British Isles was made by about one hundred people during one working week in September 1993. On any one day, there were between fifty and sixty people, the majority of whom had committed themselves for the full five days. Where this was not possible, the minimum involvement was two full days. The Robins Lane annexe consisted of a gymnasium, three science laboratories and a workshop which, together with a kitchen and dining room, provided perfect facilities.

The working procedure was simple: each person needed a board on which to place a lump of clay; a small pot of water and a pencil to make the eye holes; a foam cushion to sit on and enough floor-space to be able to 'plant' out our figures in rows of ten (for ease of counting). Everyone was encouraged to find their own way of making, following these guidelines: the pieces were to be hand-sized and easy to hold, the eyes were to be deep and close, and the proportions of the head to the body roughly correct.

The working day was 9.00 until 17.00. As people arrived each morning, Paul and Aiden, the two main labourers, began cutting and distributing large lumps of clay, using wheelbarrows, trolleys and helpers to meet demand. Once started, people quickly settled into their own rhythm of working, which gradually became more familiar. With every additional row of figures confidence grew. At the end of each day, a 'census' was taken, to total the number of figures made.

For the first two days the group worked together in the gym, the largest single space. By Wednesday the group began to spread out and 'colonise' other parts of the building. Despite the aches and pains of repetitive, physical labour, no-one gave up. As the days passed it became clearer to all what the process was about. By Friday, the school was populated by some 40,000 figures, and the group left with a feeling of immense satisfaction, at the achievement itself, and quality of the experience.

All 40,000 figures then made the journey from St Helens to Liverpool, in two lorry loads, ready for 'planting out' in the gallery.

Everyone involved in the many different stages of making Field for the British Isles - children, parents, teachers, staff at the brick factory and at the Gallery - share a real sense of personal and collective satisfaction, knowing they have created something which has a powerful, tangible energy of its own.