Donald Judd and Claes Oldenburg had a good relationship – not only a personal friendship, which was strong, but also a relationship figured through Judd’s early critical writing. Virtually all of Judd’s reviews are worth pondering, even now, decades after his career as an art critic. They remain fresh, presenting a critical model to follow rather than a historical document to be analysed. Within this corpus I often consider that the commentaries on Oldenburg are the most stimulating and provocative. Yet every time I review my interpretation of Judd’s interpretation of Oldenburg, I wonder whether readers will grasp my sense of Judd’s insights.1 In consultation with translator Jürgen Blasius, I slightly expanded my remarks on the Judd/Oldenburg issue for the German edition of ‘Donald Judd: Safe from Birds’. /fn] Do my paraphrases take a reader closer or farther from Judd’s own targets?

Judd was a quirky writer but I do not think the problem originates in his style or rhetorical manner. His rhetoric was sophisticated and may well have been adequate to his thinking and to Oldenburg’s.That may be the problem. I suspect that Judd’s thinking about Oldenburg was operating at the very limits of what words can convey coherently; accordingly, Judd had to take his rhetoric to extremes. My insecurity as an interpreter lies in the nature of Judd’s creative vision of Oldenberg and in what Oldenburg himself accomplished, rather than in some failing of the expressive or expository style of either of them. I am reminded of Clement Greenberg’s complaint (in 1967) concerning the term formalism. Too many critics, Greenberg argued, assume through their use of this term ‘that “form” and “content” in art can be adequately distinguished for the purposes of discourse. This implies in turn that discursive thought has solved just those problems of art upon whose imperviousness to discursive thinking the very possibility of art depends. … You know that a work has content because of its effect.’2 Greenberg insisted that the best understanding is experiential and should not be limited by the interpreter’s own pre-existing discursive structures. Although this issue is endlessly debatable in theory, there may little profit in the argument whenever decisions have to be made regarding elements of practice. Oriented toward what material practice could accomplish, Judd’s position was similar to Greenberg’s. In 1993, he flatly stated what for him was obvious: ‘There is a limit to how much an artist can learn in advance.’3 The same would apply to critics. They need to grasp the experience, not some concept that either precedes, encompasses, or supercedes it.

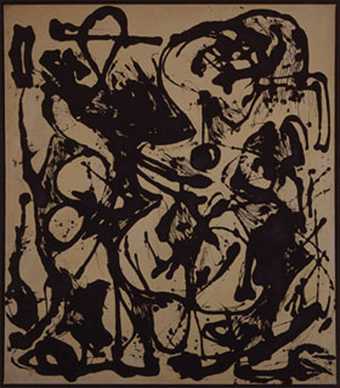

Concerning his work of the 1960s, Oldenburg himself said: ‘I want the object to have its own existence’ (a remark to which this essay must return).4 As a critic of others’ work, Judd was obligated to explain the effect an Oldenburg object produced, as opposed to restating the state it sought (‘existence’). His evaluations did not come easily and reflect candid feeling as much as conceptual analysis. In 1964, he reviewed a group of objects that included a version of Soft Switches 1964, in vermilion vinyl (fig.1), commenting: ‘I think Oldenburg’s work is profound. I think it is very hard to explain how.’5 After this bold admission, Judd noted something crucial: in significant ways, Oldenburg’s representations failed to resemble the familiar objects they called to mind; they were not ‘descriptive, even abstractly’. This is more hypothesis than fact, for who can say where the limits of descriptive abstraction might lie? When is a circle the sun, and when is it just a circle? Something about Oldenburg’s objects was causing Judd to remove them from the category of sculpture and its mimeticism. We should not expect the logic to be self-evident. Hypothetical conclusions like Judd’s tend to relate facts of one kind to facts of a very different kind. They never appear inevitable but are nevertheless convincing. Like good intuitions, they convince without offering compelling sets of reasons.

Fig.1

Claes Oldenburg

Soft Light Switches 1964

Vinyl filled with Dacron and canvas

Courtesy Claes Oldenberg and Cossje van Bruggen © Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen/ Licensed by VAGA, New York

Appropriately enough, Judd became a critic by happenstance without compelling reasons. In 1959 he attended Meyer Schapiro’s art history seminar at Columbia University where he encountered Thomas Hess as a guest speaker. Hess announced that his journal Artnews was looking for new writers for monthly reviews and asked whether any of the students were interested. Needing a source of income, Judd volunteered. He wrote for three issues of Artnews during the fall of 1959, but then moved to Arts Magazine fearing that Hess was going to dismiss him. As Judd recalled a decade later: ‘[Hess] did not like it. He wanted [my writing] to be more poetic. He said I was not saying anything.’6 Yet from the very start, it seems that Judd had certain notions in mind, conditions of which he approved, specific qualities that he was probably seeking in his own art at the time, as it evolved from two dimensions into three.

Judd’s earliest reviews contain elements of appreciative analysis that he would repeat in increasingly sophisticated form as he developed his thinking as writer and artist. On one of his first assignments, October 1959, he reviewed Yayoi Kusama, characterising her work as ‘both complex and simple.’7 Hess may have thought that this type of statement was a hopelessly vague generalisation, if not a gratuitous contradiction; but it was actually a minor articulation of a major insight on Judd’s part. In December 1959, reviewing Josef Albers, Judd said the same kind of thing with more specificity. He contrasted what he called the ‘rigidity’ of Albers’s geometry to the ‘ambiguity’ of ‘unbounded’ effects of his colour.8 In Kusama’s case, art became complex and simple; in Albers’s case, somewhat analogously, art became ambiguous and precise.

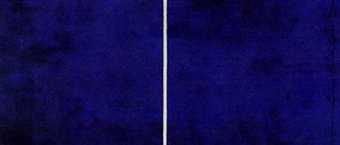

A few months later, Judd embedded some remarks on Jackson Pollock (see Number 19, 1951, fig.2) within a brief review of Helen Frankenthaler, to Frankenthaler’s detriment: ‘Pollock achieves generality by establishing an extreme polarity between the simple, immediate perception of paint and canvas – a reduction to unexpandable sensation – and the complexity and overtones of his imagery and articulated structure.’9 He was claiming that Pollock attained a coherent, total image without obscuring any of the disparate marks of paint. Nor did the parts combine to create the whole. Rather, the parts and the whole existed as very different entities – in fact, so dissimilar (as Judd would explain in later statements on Pollock) that the appearance of the whole could not be predicted on the basis of the parts. This is why he used the word ‘polarity’. A polar differential is the widest possible gap. He also used the phrase ‘extension of extremes’ to the same purpose, as he moved toward his conclusion: ‘The level of quality of a work can usually be established by the extent of the polarity between its generality’ – the total image, ‘and its particularity’ – the individual marks.10

Fig.2

Jackson Pollock

Number 19 1951

Private collection © 2004 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1963 and 1965, between the time of his earlier and later comments on Pollock, Judd approached the same principle through a consideration of the relief sculptures of Lee Bontecou (see Untitled 1960, fig.3): ‘Often power lies in a polarisation of elements and qualities, or at least in a combination of dissimilar ones.’11 Some of his verbal playfulness appears as he elaborates on the features of Bontecou’s reliefs, punning on whole and hole: ‘The image [of a volcano-like mound with a hole], all of the parts, and the whole shape are coextensive. The parts are either part of the hole or part of the mound which forms the hole. The hole and the mound are only two things [that is, they constitute a single opposition], which, after all, are the same thing [a polarised but integrated image].’12 From the character of her art, Judd inferred Bontecou’s political personality as someone immune to the usual dogmas: ‘Bontecou is obviously unimpressed … by artistic generalisations. … [Her] reliefs are an assertion of herself, of what she feels and knows. Their primitive, oppressive and unmitigated individuality excludes grand interpretations.’13

Fig.3

Lee Bontecou

Untitled 1960

Collection of halley k harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld, New York © Lee Bontecou / courtesy Knoedler & Company, New York

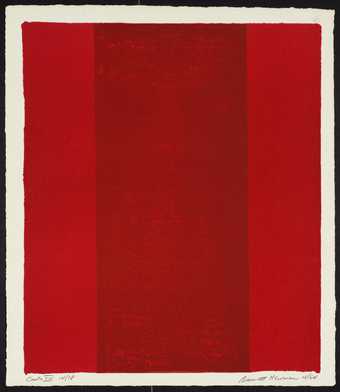

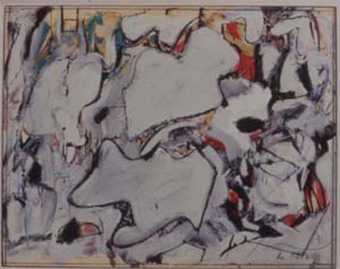

I think Judd wanted a certain lesson for life to emerge from his kind of critical writing. He seems to have recognised that when an artist sets the main aspects of a work in some kind of opposition, while also preventing the separate parts from being subordinated to a generalised harmony or composition, then the entirety of the work remains alive in the viewer’s perceptual experience – every part, every sensory quality of it, and all the emotional and intellectual qualities as well. Every element (including the totality) becomes focused, as if art allowed its viewer to function on every level with equal acuity, never sacrificing one area of human potential for another. To understand the conditions of a life within a specific social and physical environment, Judd implies, a person needs to concentrate on what can be known through the most immediate forms of experience, resisting the generalisations of categories, clichés, and logical inferences. Yes, try to grasp the big picture (the ‘whole’); but do not allow it to rule over the independent significance of a detail (a ‘hole’) With this approach to life, Judd admired Barnett Newman (see Primordial Light, 1954, fig.4) just as he admired Bontecou: Newman’s art ‘does not claim more than anyone [any one person] can know.’ Judd meant that every formal element in Newman’s painting was no more than it appeared to be, and appearances were there to be experienced as something entirely real: ‘The color, areas, and stripes are not obscured or diluted by a hierarchy of composition and a range of associations.’14 This was an art that performed its own judgments, without referring to established belief and the common, acculturated forms of experience that people rarely investigate for themselves.

Fig.4

Barnett Newman

Cathedra 1951

Collection Stedelijk Museum © 2004 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Newman’s art ‘does not imply a social order’, Judd reasoned; it offered no grounds for a generalised theory.15 Perhaps, then, Newman was risking incoherence, or the sense of nonsense that might derive from simply setting one thing against another, pale cerulean blue against deep black, with the two barely relating, if at all. If such a thing were done for the sake of incoherence or nonsense itself, and merely intended to be provocative, it would be a new Dadism, rather than a critical skepticism. Newman, in fact, had denounced the Dada artists for their implicit claim to know what art was and what it was not.16 However nonsensical, Dadaist actions were directed toward a conceptual goal; they reduced the experience of art to a philosophical principle, a kind of intellectual idealism. Such generalisation could not be true to conditions at hand. On these matters, Newman and Judd were in complete agreement. So Judd had a least two admired models to follow from the Abstract Expressionist generation, Pollock and Newman (and he liked Mark Rothko as well). Artists of the New York School who practised figuration, such as Willem de Kooning, brought about a different situation. Judd disliked the fact that de Kooning subordinated the materiality of the painter’s mark to emotions associated with the experience of the body, even if that body were internalised as the artist’s own. According to Judd, de Kooning displaced the specificity of sensation with emotional generalisation: as a referential response to bodies and objects, the ‘expressive brushwork … portrays immediate emotions. It does not involve immediate sensations’.17 Here I can not agree with Judd’s conclusion that de Kooning fails to respond sufficiently to material circumstances, but his point is important for what follows.

In 1966 Judd participated in a symposium at the Jewish Museum, moderated by Barbara Rose. The transcript from the Rose archive differs from the one in the museum archive, which is quite rough. Apparently, the Rose version went through an editing process to restore its fluidity and also expand its scope. Additional sentences were most likely inserted by Judd to set the historical record straight. In these supplementary remarks, he emphasises his affinity to Bontecou, John Chamberlain, and Oldenburg, three artists about whom he had already written in some detail. ‘One of the reasons I stopped painting,’ Judd tells Rose, ‘was that Oldenburg’s work was much stronger than anything I could possibly make in a painting’.18 Why would Judd be so attracted to Oldenburg, who represented clothing, foodstuffs, household appliances and furnishings? Why would this practice not lead to de Kooning’s kind of compromised expressionism – part figurational, part abstract – which Judd believed could only generate the shallowest emotions?

In 1968, this enigma troubles Lucy Lippard, an unusually astute critic, as she interviews Judd. Lippard was well aware that Judd had featured Oldenburg in his notorious article ‘Specific Objects’, first composed in 1964. Initially, she objects to the anthropomorphism of Oldenburg’s art, which seems to conflict with Judd’s principles. Judd replies that Oldenburg is not ‘anthropomorphic quite’.”19 A lot hangs on his appended word quite. Judd had already distinguished Oldenburg’s anthropomorphism from the usual kind by calling his type ‘extreme’ and ‘blatant’ – so extreme that it did not seem comparable to what people identified as anthropomorphi.20 Yet there was no other name for it. As a pragmatist, Judd knew that things tend to have more or less of a quality, only rarely all or nothing. Whether a person regards qualitative variance in a given characteristic as generating sameness or difference becomes a matter of perceptual attitude (in turn, perhaps instilled by temperament or emotional attitude). Judd preferred to use geometric forms in his art, as opposed to Oldenburg’s organic forms; yet this distinction did not always make a difference, nor did it prevent other abstract art from being just as anthropomorphic as organic figuration. Abstract, constructed form – not abstraction from or of something else – was Judd’s personal way of trying to avoid artistic clichés. With his dry humor, he imagined a condition potentially better for art than anyone had yet been able to achieve, including himself: ‘A form that’s neither geometric nor organic’, he wrote in 1967, ‘would be a great discovery’.21 He also wanted to escape the generalities known as ‘order’ and ‘disorder’.22 Any concept that might categorise and contain his art, or even exclude it, was its inadequate antithesis.

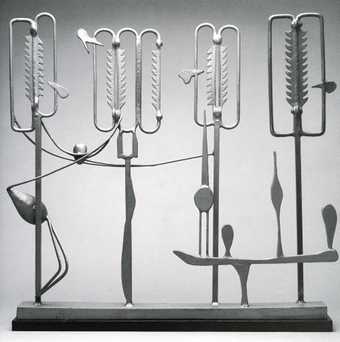

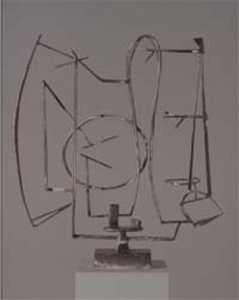

Fig.5

David Smith

Stainless Window 1951

Courtesy The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas © Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Proceeding with his defence of Oldenburg, Judd raises the example of David Smith. He regards Smith’s sculpture as the more anthropomorphic of the two, despite the fact that Smith was working in terms of abstraction, whereas Oldenburg was making expressive representations of real things in the human environment. One would think that Oldenburg already had two strikes against him when it came to anthropomorphism, for he created objects related to the human image as well as to human use. Judd understood that Lippard needed some kind of explanation: ‘Smith … is seeing it [the anthropomorphic quality] out there and it is in the work, he’s feeling it out there and it is in the work and it is beyond him.’ Like de Kooning, Smith seems to combine the anthropomorphism of his forms with the anthropomorphism of things he might observe – as Judd says, ‘it is in the work

- and

it is beyond him.’ Although the example is not Judd’s, perhaps we grasp his reservation about Smith through a sculpture such as Stainless Window 1951 (fig.5); it resembles de Kooning’s ‘abstractions’ of the late 1940s (see Attic Study 1949, fig.6), though in shallow relief. The tensile organicism of de Kooning’s and Smith’s imagery evokes human bodies and the physicality of familiar objects – whether the artists’ forms are abstract or representational, whether set in a vertical or horizontal format, whether created of paint or metal, and whether or not the tensile factor might relate to those materials. With de Kooning and Smith, the general anthropomorphism is not merely set in opposition to a more specific material factor but (in Judd’s view) dominates it.

Fig.6

Willem de Kooning

Attic Study 1949

Courtesy The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas © 2004 Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

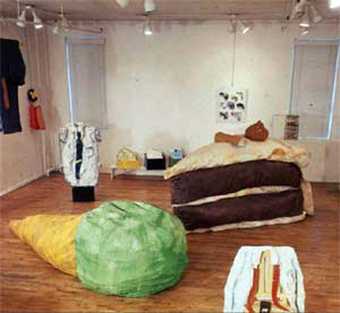

Continuing to address Lippard, Judd elaborates on Oldenburg’s difference: ‘Oldenburg is so far over the hill that it is only Oldenburg, you see, in which case it is sort of turned full circle and is not really anthropomorphic in the old sense.’23 Oldenburg’s works are ‘not really about the objects … [Instead, they’re] what Oldenburg feels. … It is Oldenburg’s interest in these things. So there’s really nothing about the ice cream cone as an ice cream cone’ (see Floor Cone 1962 (fig. 7). Here Lippard must object again, for Judd is seeing differences where there should be none: ‘I do not know how you really split that,’ she replies. ‘I can vaguely sense what you’re talking about but I do not think that it makes any sense’. I sympathise with Lippard; as close as she was to Judd’s situation, she was having trouble comprehending his thinking. Judd was not daunted and replied in turn: ‘Look, you feel something about a certain object. It is obvious.’ But (I must comment) it is not obvious, because Judd has already said, ‘[it is] not really about the objects.’ Perhaps ‘you feel something about [the] object,’ but when the feeling is strong, the object ceases to matter. The art object related to it becomes all feeling.

Fig.7

Claes Oldenburg

Floor Cone 1962

as installed at Green Gallery, New York, Fall 1962

Canvas filled with foam rubber and cardboard boxes, painted with synthetic polymer paint and latex

Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York © Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen / Licensed by VAGA, New York

Judd reaches Lippard by distinguishing between attributed feelings and felt feelings: ‘You look at all the things you look at or deal with and you know you have feelings about them; it is pretty obvious. But the fact is that they have no feeling or meaning or anything in themselves.’ Like a good American pragmatist, Judd can extend this insight to almost anything: ‘All of European art is really involved in reading things into things. You look out there and somehow what you feel is supposed to be out there.’ Judd’s problem with conventional art, including nearly all modern art, is that it accepts a preconceived notion of what an object signifies – matching feelings to things, and things to feelings. To the contrary, with Oldenburg (as Judd says), ‘it is only Oldenburg.’ If a specific feeling appears in the form of an Oldenburg art object, we feel it because the artist felt it, not because of some general correlation that results in a rule (such as: all toggle switches that come in pairs are breast-like). This is the same type of claim Judd was making for Newman’s abstract paintings around the same time, 1964: Newman represents no more than his personal experience. Despite the representational quality of Oldenburg’s work, Judd asserts that (like Newman’s) it does not depend on outside objects. Oldenburg starts from an object but develops that thing in a chosen material according to his feelings for the material as much as for the form it assumes. The difference between what Oldenburg does and what (in Judd’s opinion) de Kooning and Smith do may seem to hinge on a very fine point, so fine that it can escape attention; yet, to Judd it was critical. In the end, there is no ice cream cone, no generalised cultural artefact, but something new that exists only because Oldenburg created it – ‘new’ not in the sense of some radical originality, but new because it is a specific object with defining properties best understood through direct experience. To view an Oldenburg object is to acknowledge its specificity, not its deviation from a cultural template.

Fig.8

Claes Oldenburg

Bedroom Ensemble 1963

1/3, as installed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1974

Wood, vinyl, metal, fake fur, muslin, Dacron, polyurethane foam, lacquer, etc.

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa © Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen / Licensed by VAGA, New York

In his writings, Judd gave most of his attention to Oldenburg’s soft sculptures and contrastingly hard Bedroom Ensemble, 1963 (fig.8). Consider first what he says about objects such as Floor Cone (fig.7) and the various versions of Soft Switches (fig.1): ‘The trees, figures, food or furniture in a painting have a shape or contain shapes that are emotive. Oldenburg has taken this anthropomorphism to an extreme and made the emotive form … the same as the shape of [his sculptural] object, and by blatancy [he has] subverted the idea of the natural presence of human qualities in all things. … Oldenburg exaggerates the accepted or chosen form and turns it into one of his own.’24 In sum, Oldenburg divorces the conventional thematic form or image from its conventional emotional content. This is why his objects become his own, and as his own, they also become ‘objects as they’re felt, not as they are. … They’re exaggerated, as [personal] interest is, gross and overblown.’ Having mentioned that Oldenburg makes hard objects as well as soft ones, Judd inserts a sentence that may seem to come out of nowhere: ‘A girl said once that sometimes the corners of things would seem to be points pointing at her.’ In fact, this serves as an example of a specific emotion detached from a general image; the identity of the object does not matter as long as it has a corner. In the girl’s eroticised emotional life, corners are exaggerated, blatant, extreme. Eventually, Judd concludes: ‘The reference to objects [in representational art] gives [the basic emotive forms -corners, for example,] a way to occur. The reference and the basic form as one thing is Oldenburg’s main idea’ – that is, the ‘main idea’ for his new three-dimensional object.25

If this still puzzles (and I believe it does), imagine that Oldenburg is using organic representation to reach the point Judd might reach through geometric structure. It seems that Judd identifies Oldenburg’s referential image as conventional and general, distinguishing it from the form developed through the artist’s personal interest; and then Judd claims that Oldenburg’s art combines these two disparate qualities – image and feeling – combines them as ‘one thing,’ his ‘main idea’. This is the mysterious part, but we can see that it follows the pattern of Judd’s appreciation of Pollock’s abstractions, which oppose aggressively sensuous marks to a general, unified image that never reduces to the sum of its sensuous elements. Nor do the parts become subordinate to the whole.

Judd first addressed Oldenburg’s Soft Switches in 1964, the year they were made. Here the generalised image was of functional switches, while the sensuous element, analogous to a painter’s constitutive marks, became erotic – erotic because of the soft or flaccid nature of the canvas or vinyl as well as the structural allusion to nipples, and further, because those nipples evoke breasts. But perhaps they do not … ‘quite.’ As Judd states, ‘there are not two breasts, just two nipples. The two switches are too distinct to be breasts.’26 He means that they retain their identity as switches, yet their form describes neither switches nor breasts. Rhetorically, for what it may be worth, the dominant figure in Judd’s writing is not metaphor. He does not relate toggle switches to human nipples by sensuous, metaphoric resemblance. Instead, he invokes the more troublesome figures of syllepsis and catachresis. With syllepsis, we understand the meaning of a term in two opposing directions, one of which usually appears more proper than the other. An example: Hope sank with the ship. Because ships are solid objects, we know they can sink. But does hope sink in the same sense, in the same direction? How do intangibles like hope and other emotions move at all? Hope cannot sink metaphorically because it bears no resemblance to a solid object, or even to heavy air. To describe it as moving somewhere is to enlist a different rhetorical figure – catachresis – an indication of cognitive desperation, a figure to be used when no other device is available. With catachresis, we borrow a term that applies elsewhere, and we extend it.

In rhetorical practice, both syllepsis and catachresis represent the kind of ‘extension of extremes’ that Judd appreciated in art practice. Rather than operating like refined poetic devices, bringing nuance to existing images, these rhetorical figures force thought into unfamiliar realms. Although Judd sometimes resorted to metaphors – and who does not? – his writing is better characterised by catachresis and syllepsis. He took pleasure in pointing out that Jasper Johns’s Thermometer 1959, as he wrote, ‘has one’, that is, the painting with the title Thermometer also has the actual object, a thermometer.27 This is an instance of syllepsis. Catachresis and syllepsis bring a strange quality of literalness to Judd’s most figurative descriptions, as Thomas Hess must have intuited right at the beginning. I believe Hess knew that something disturbing was occurring in Judd’s writing but could not characterise it. He just knew that he did not like it, as Judd later recalled. To Hess, who packed his own writing with metaphors, Judd’s reviews lacked style. One might expect this, because writers resort to syllepsis and catachresis when faced with a situation in which words fail them, when no more agreeable figure will work because the effect being described lies outside the range of all standard metaphors. Catachresis is the absence of style and stylistic eloquence. It strong-arms language. Yet, with catachresis, a writer discusses what otherwise can not be discussed.

A critic relying on a concept of metaphor to guide the evaluation of Oldenburg might well turn negative, having extinguished the specificity of the art by generalising its features. Consider a statement by Max Kozloff, to which Judd appears to have objected: ‘[Oldenburg] strives for a metaphor, not of the motif itself [the object represented], but of particular attitudes towards it. His pastries are wreathed in an aura of glutinous ecstasy. … [He] does not lift a thumb that is not satirical, and hence finally reportorial in intention. Ultimately, his pieces are in danger of becoming what they are parodying.’28 In Judd’s view, parody and reportage were beside the point. If the emotion was ecstasy, then the object was an ecstatic object, not one merely referring to ecstasy: ‘Oldenburg, who has done something artistically new, as Max Kozloff in Art International says he [has] not, makes his cakes and pies and other foods and articles actual objects, which is different epistemologically from illustration.’29 Parody illustrates.

This is why Judd will state of Oldenburg, ‘the switch does not suggest this single, profound form [the archetype of a breast] but is it, or nearly it.’ Metaphor suggests; it creates evocative analogies. But catachresis says, no, this is no time for suggestion, no time for mere comparison and approximation; the situation is this way, even though we find no word for it. Metaphor generalises; catachresis specifies.30 Having committed himself to a hypothesis specific to Oldenburg’s art, Judd could then explain it in general terms: ‘Ordinarily the figures and objects depicted in a painting or sculpture have a shape or contain shapes that are emotive. Oldenburg makes one of those subordinate shapes the whole form.’ The exaggerated form becomes distinct from the standard image of the object, because the object has been transformed in accord with the artist’s interest. Perhaps now we grasp what Judd means when he says: ‘The reference and the basic form as one thing is Oldenburg’s main idea.’31 We would not expect the reference and the basic form to exist together in this way (as opposed to forming a metaphoric comparison between them); but they are together, as they are nowhere else, both polarised and integrated.

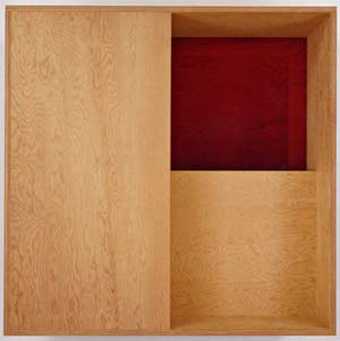

For his Bedroom Ensemble, Oldenburg took a perspective drawing of a set of bedroom furniture, the kind of rendering found in newspaper advertisements for clearance sales, where the typical geometry would include trapeziums, rhomboids, rhombuses, and ellipsoids – rectangular and round figures skewed by imaginary angles of view.32 He then built his own set of furniture in three dimensions, giving the pieces the forms they had as two-dimensional drawing. In his description, Judd calls the quadrilateral forms ‘parallelogrammatic’; this may be a clever use of catachresis to signify the appearance in art of forms as new and strange as Judd’s own.33 Where a right angle in a real three-dimensional bed might have translated into an acute angle in a perspective drawing, there is an acute angle in the bed Oldenburg created, as if he were following an interest in drawings as much as in bedrooms. The Bedroom that he designed put the accidental angularity of things seen in perspective on an equal footing with the rectilinear geometry of typical objects, objects idealised in our minds as if never subject to the illusions of perspective. For Judd and Oldenburg, idealisation constitutes the fantasy, and perspectival illusion is the reality of any actual situation. This is precisely the kind of realisation that comes through the rhetorical figure of catachresis, which establishes an accident of appearance as the normal or standard view. For example, we refer without hesitation to the legs, arms, and back of a chair, but hardly ever notice that chairs usually lack a head, which ought to disarm the metaphor – but it is not one. ‘Arm of a chair’ is a textbook example of catachresis. Here the word is entirely specific to the thing; the arm of a chair has no other name.

Oldenburg’s reflections on his work are consistent with Judd’s. In notes of 1976, he emphasised the disjunction of the formal look of his installation objects from the concepts associated with their identification: ‘Geometry, abstraction, rationality – these are the themes that are expressed formally in Bedroom. The effect is intensified by choosing the softest room in the house and the one least associated with conscious thought. … Hard surfaces and sharp corners predominate. … [The] subject matter is not necessarily an obstacle to seeing “pure” form and color.’34 Oldenburg understood that he had created a ‘pure’ abstraction that was also purely representational; and he had done this without resorting to a hybrid expressionism as de Kooning or Smith did. Judd referred to Bedroom Ensemble as ‘grossly geometric,’ indicating that here the element of exaggeration was the geometry, the angularity, the rigidity of things as they are felt, not merely seen.35 Around 1963, while Oldenburg with his Bedroom Ensemble was creating a hard version of a ‘soft’ space, he was also translating the soft effects of painting into nominally ‘hard’ sculptural form – a form that became soft not metaphorically but actually. In Oldenburg’s objects, the fluidity of paint in two dimensions became the flaccidity of canvas or vinyl in three dimensions. As he said, he realised ‘the tendency of a hard material [sculptural form] actually to be soft, not look soft.’36 This would accentuate the emotional force of the created object, conveyed by its softness or hardness, whatever its representational identity. The polarity between emotional sensation and representational concept would exist in the hardness of Bedroom Ensemble as well as in the softness of Floor Cone. ‘Obviously what you feel and what things are are not the same,’ Judd wrote in 1967.37

For both Judd and Oldenburg, the harsh angularity of Bedroom Ensemble – a formal element inspired by an interest in the feeling it generates – distanced the emotional impact of the object from its conventional, identifying image. Oldenburg noted that he had created a hard version of the softest room of a house, soft by conventional association. He wanted to:

remove the object from context … to individualise it … to create an independent object which has its existence in a world outside of both the real world as we know it and the world of art. … The object will slip out of whatever definition it may be given. … My intention is to make an everyday object that eludes definition. … I want the object to have its own existence.38

I am reminded of what Judd wrote in 1964, not as a reference to Oldenburg’s work, but at more or less the same moment that he may have been pondering it: ‘Things that exist exist, and everything is on their side … Everything is equal, just existing.’39 Merely by existing, the things that exist, like the accentuated brushstrokes of Pollock or the exaggerated qualities of an Oldenburg object, have already beaten the odds against the chances that their particular configurations would ever be actualised. Art can be made from very little, so long as the little things acquire a forceful, ‘interesting’ existence.40 Thinking of Oldenburg’s Floor Burger 1962 (fig.9]), Judd remarks: ‘Three fat layers with a small one on top are enough.’41

Fig.9

Claes Oldenburg

Floor Burger 1962

Canvas filled with foam rubber and cardboard boxes, painted with latex and Liquitex

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto © Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen / Licensed by VAGA, New York

Much more could be said concerning Judd’s way of linking a writing style to an art style. Catachresis and syllepsis are not the ultimate keys to the puzzle but provide a pragmatic way of dealing with it. There are many other ways. I think Judd especially appreciated that Oldenburg’s Bedroom Ensemble and a number of related works demonstrated the potential of perspective to be at once the most specific of sensory phenomena and the most generalising of perceived concepts. This happens to be the way he thought of proportion – that it could be at one and the same time the most particular and the most general relationship that a work might exhibit. The ratios were general, but what an artist did with them was specific. If, in Oldenburg’s Floor Burger, it was enough to have three big things and a little thing, Judd himself could work endlessly with the complexities of 1 to 1, or 1 to 2, or 1 to 3, maintaining a sense of generality that would lead right back to the specificity of the particular work (see Untitled 1987, fig.10). His boxes, both early and late, demonstrate that whatever theory of proportion might be considered and however simple it might be, actual practice brings surprises.

Judd’s art, like Oldenburg’s, faces the fact that we acknowledge general conditions at hand (social, cultural, emotional, material) while actively creating something specific from their situation. We need to keep the two realms separate and equal, understanding that neither the totality nor the detail eliminates its counterpart. We must resist becoming ideologues (totalisers), yet we need to see the whole. Works of art are modes of integration – integration without subordination of the parts.

Fig.10

Donald Judd

Untitled 1987

Plywood with red Plexiglas

© Donald Judd Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Early in 1993, just about a year before he died, Judd wrote of space in a way that parallels his sense of emotion and perspective in Oldenburg: ‘There is no neutral space, since space is made. … My smallest, simplest work creates space around it, since there is so much space within. … Space is new in art and is still not a concern of more than a few artists. … There is no vocabulary for [its] discussion.’42 When no vocabulary exists, rhetoric resorts to syllepsis and catachresis, which create a vocabulary outside the usual poetry as well as outside the usual logic.

Did Judd have a rhetoric of three-dimensional form? Sylleptically, he combined what was given at hand with what he chose to do, making strangely integrated structures that move beyond familiar logics of form. His large, site-specific concrete ring of 1971 is a striking example (fig.11). While the top edge of its inner surface remains level, the top edge of its outer surface parallels the ground, maintaining a height of four feet above that given feature of the land – an arbitrary measure, but calculated along with the inner, constant edge to allow the interior space of the ring to be seen. All is exposed. The ring itself is eighteen inches thick and requires a complex bevel to accommodate the shifting difference between its inner and outer surfaces. Here a single object set in the land creates different spaces of different character, inside and outside its bounded surfaces. Given Judd’s understanding of Oldenburg’s art, it may be that the outer surface was his way of dealing with representational reference, for it blatantly mimics an aspect of the land, whereas the inner surface is just as forcefully abstract in its escape from reference. The most obvious feature of the ring is its existence as a single unit. In his boxes, Judd called the effect of red and black a ‘two color monochrome.’43 I suppose that by analogy – would he have objected to this one? – his concrete ring could be called a bilateral unilateral. Its complexly canted surface gestures toward the given land and toward Judd the willful artist, accomplishing these very separate actions as one.

Fig.11

Donald Judd

Untitled 1971

Outdoor concrete ring made for Philip Johnson

© Donald Judd Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY