The structural treatment of deteriorated oil paintings on canvas is a major concern of paintings conservators. In the past, the attachment of a second canvas to reinforce the weakened original was universal practice. This was called re-lining and later became known as lining. But in recent years the value of lining has been questioned and its disadvantages documented. A major change of opinion has occurred, reinforced by modern attitudes to conservation which place greater emphasis on preserving the original state of the canvas support and applied paint film. These attitudes in part derive from a more academic education that conservators now receive. This has largely replaced apprenticeship training, which tended to reinforce the strengths of existing practice. Now, a less interventionist approach is taken. But this approach is very dependant on the accuracy and relevance of engineering models derived from recent scientific research. The application of this knowledge to conservation practice creates an ongoing dialogue about the aims, aesthetics and ethics of conservation.

The 1974 Comparative Lining Conference

In 2004 the UKIC held a meeting on the subject of ‘Alternatives to Linings’.1 The meeting coincided with the belated publication of the often referred to papers from the Greenwich Comparative Lining Conference of 1974.2 These two events were an opportunity to take stock of changes during the last thirty years to conservation practice for the structural conservation of canvas paintings. This paper presents an overview of the subject and is illustrated by some examples of solutions to structural problems that have been used regularly.

The Greenwich Conference was a very significant event since it was the first opportunity to discuss this subject. It brought together a group of specialists from around the world with very different views of what was required from a lining.3 There was little meeting of minds on solutions, each described their own practice, but the full range of problems was at least identified.4 In retrospect its main value was to identify the inadequacy of our understanding.

After the conference, since there had been no agreement on what constituted a good lining, W. Percival Prescott, co-ordinator of the conference, called for a moratorium on lining to give conservators time to take stock of the situation.5 This was not what I wanted to hear and it took me some time to see its value. We had identified a hugely important issue in conservation that needed solving. My initial response was a desire to find out more and to experiment with all the options presented.6 But in museums, so the argument goes, we are able to defer lining because we know that paintings will be kept in acceptable conditions and remain available for re-examination, which allows us to reconsider our treatment if it continues to cause problems. This is not entirely true but in a museum the argument for carrying out a lining has a higher threshold.

Lining was seen as a solution but the criteria for lining had never been properly addressed. At Greenwich there was much confusion between the need to provide a sound support and the need to re-attach the paint film to the original canvas. What is a sound support? One that copes with handling and transport, tensions from humidity and temperature changes, is chemically stable and visually acceptable. A marouflage is a sound support, but that is an extreme solution. What about more subtle solutions? It was clear that we needed to know much more about the painting and the conditions to which we intend to expose it.

No-one had addressed the most fundamental questions. What is happening within the structure of a canvas painting? What forces exist within the layers of a painting on canvas? What is their magnitude? Where do they act? What are their consequences? We knew that when a wood panel is constrained it causes huge forces that can crack it from end to end. We knew that when rabbit-skin glue dries it can pull off a layer of glass from inside of a beaker. We knew that pre-stretching can cause a canvas to split. We knew that in dry conditions paintings become very brittle and can cause paint to flake. We knew that in humid conditions canvases can contract, sometimes dramatically losing areas of paint at the edges – the notorious shrinkers. We knew that with heat and pressure we can distort seemingly solid paint, mould it to our advantage or fail to control the application to everyone’s disadvantage.

Whether to line

Fig.1

Thomas Gainsborough

An Old Horse c.1755 detail

(raking light photograph)

oil on canvas, Tate.

This is an example of a painting that has suffered damage during a glue lining.

The canvas texture is reinforced into the surface of the paint and the brush strokes have lost their crispness

© Tate

By examining many examples of glue lined paintings and their conservation records, it was clear that the results of glue lining, particularly in the United Kingdom, had been disastrous (fig.1).7 Impasto was squashed, the canvas texture re-inforced in the paint and the precious evidence of artists’ brush-strokes were forever lost (fig.2). By contrast, the setbacks from modern lining practice are relatively tame. But, of course, we are all personally responsible for the effects of the linings that we undertake.

Fig.2

W. R. Sickert

Tipperary 1914

Oil on canvas (detail), Tate

On an unlined painting we may appreciate the spontaneity of an artist’s brushstrokes, the nature of the paint and the qualities of stretched canvas

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert

Responsibility is the key issue. In the past, the lining process was carried out by liners (or re-liners), who were often employed by restorers, who in turn were responsible to the museum curator or the painting owner. Was the continued insensitivity to lining damage caused by this arm’s length responsibility? Or was it simply that damage was thought to be acceptable as an inevitable side-effect of the need to save the canvas from falling apart? As I saw more old glue linings it became clear that nineteenth-century liners such as Morrill continued to cause the same kind of damage over and over again and that this damage was accepted by museums, which were prepared to send more paintings to be lined.8

Interestingly, our recent studies of some nineteenth-century artists’ techniques have also shown that artists such as William Holman Hunt, Ford Madox Brown, Sir John Everett Millais and James McNeill Whistler were getting their canvases lined very early or even during the painting process. They had no concerns about flattening and weave re-enforcement and we suspect that in some cases they were happy for their canvases to take on the characteristics of the lined old masters that they had seen in museums.

In the past our attitudes to physical and structural threats to a painting have owed more to the excesses and limitations of our own imaginations. We may imagine that our treatment will last indefinitely and cope with a range of unpredictable problems. In this case we are likely to go too far in our intervention. Alternatively, we may imagine that we must not contaminate our painting with unnecessary material and in that way fail to prevent deterioration. The key is to have an accurate model of the future use of the painting and the consequences of an intervention.

Understanding the problem

Since Greenwich we have made much progress in understanding how a canvas painting is constructed and how it responds to its environment and to our actions. Paul Ackroyd has produced an excellent review of the changes in lining practice.9 In particular, careful measurements of the moisture response of painting materials have been carried out by Mecklenburg, Hedley and Michalski.10

Conservators began to understand that not only the canvas and sizing but also the oil paint could respond to moisture very significantly, if slowly, and that the moisture content influenced the mechanical properties of the paint, making it more susceptible to the effects of heat and pressure. Moisture treatments were explored. We could soften some paints but not usually the lead whites. Glue paste linings and other linings involving heat and moisture exploit this moisture response whereas linings using wax and synthetic materials had been invented more recently to avoid it. But glue linings are more effective at actually flattening raised cracks, not simply holding them tightly in plane. Oil paint moisture response also explains why so much damage has been done by glue liners in the past. With enough heat and pressure we could mould the paint into all sorts of interesting shapes.

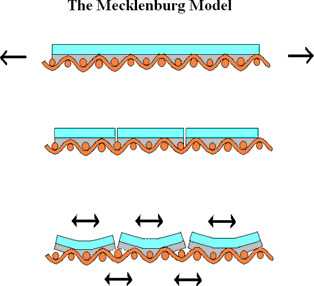

Mecklenburg revolutionised our view of the canvas as support by showing that the glue layer in a new painting carried much of the load (fig.3).11 The ground and paint layers also carried significant parts of the load, and the relationships between the layers changed with the changing humidity environment. As the painting aged and cracked the forces became disrupted in the painting plane and created the familiar raised cracks and cupped paint. We could now begin to appreciate why glue paste lining was effective at holding down raised cracks, whereas other methods were not. The persistence of the nineteenth-century glue liners at least seemed rational. Could we learn from their success in flattening cupping and still avoid the unwanted consequences inherent in their approach?

Fig.3

The diagram illustrates how all paintings on stretched canvas deteriorate, first through embrittlement and cracking, then through long term relaxation under tension. Much of the tension is carried in the paint and ground, not in the canvas, but where the paint cracks, all the tension is taken by the canvas. Re-alignment of forces causes the islands of paint to cup and separate from the canvas

© Tate

Thanks to Hedley, shrinkers are no longer a mystery. Conservators understand the behaviour and effect of a glue layer sitting as a separate layer on top of the canvas because it was applied cold by spatula in a thick gelatinous solution by a colourman such as Roberson. Above 75–80% RH a linen canvas tends to shrink and animal glue loses its strength. Tightly woven Ulster linens were not as solid and dependable as we had previously thought. We looked with new respect at the flimsy open weave Belgian canvases used by many French painters of the twentieth century.

More recently work by Young and colleagues has continued to develop our understanding, filling in more detail about internal and external forces, generating computer models of how a painting and canvas behaves, and beginning to measure the effects of specific conservation treatments.12 Should we be lining onto stiffer fabrics that match the glue for load carrying? We are still using the same specification of polyester sailcloth that Hedley found at the Earl’s Court Boat Show in 1981.13

The realisation that a lining canvas is only one of several important components that hold together a canvas painting has changed our frame of reference. Separating the consolidation process from the lining process was a crucial change in thinking.14 If each process has to be justified separately and a lining canvas is not a unique structural component, the arguments in favour of carrying out a lining are rare. That has been our experience. It has been possible to investigate the effects of moisture treatments, adhesives and preventive treatments in isolation from lining. Indeed, we have been able to show that we could create nearly all the disadvantages of lining: weave emphasis, excessive flattening, the marouflage-look, squashed impasto and moating without attaching a second canvas.

Strip-lining

Given that in the past we understood very little about the complexities of stretched canvas paintings and even now we do not understand everything, the practice adopted by most conservators has been to intervene as little as possible. But when a canvas is around a hundred years old and beginning to show the familiar signs of deterioration, we need to intervene.

Often the tacking edges are more damaged than the bulk of the canvas because of the effect of the rusted tacks and resinous wood. We rarely remove a canvas from its stretcher unless it is absolutely necessary. When we do, we risk damaging the tacking edges, which may not be strong enough to allow re-stretching. It is then that we resort to strip-lining, the application of a strip of canvas to reinforce the original edges (fig.4).15

Fig.4

A 150 year-old primed canvas which has never been painted displays all the basic deterioration characteristics of a finished painting on a stretched canvas

© Tate

Strip-lining is often done with polyester canvas and BEVA adhesive (ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer). This has proved to be effective over many years. The polyester is thin, stable, and load-bearing and BEVA is flexible and provides good adhesion. It is heat sealed at 65 degrees centigrade. There is always the question of how far to extend the strip lining into the picture plane. It must be far enough to carry the load across the weak edges. Deformation in plane at the strip-lining edge is much less of a problem with thin polyester and flexible ethylene vinyl acetate.

Strip-lining has largely replaced lining since it begins to address many of the problems that would once have put the painting in the category to be lined.

Tears

Tears are often cited as the reason for lining and indeed major tears equivalent to half a painting dimension or more need extra support. But most small or medium tears can frequently be repaired in situ and need not involve lining. The canvas is not normally removed from its stretcher. The torn area is treated with moisture using a brush or swab to shrink the extended yarns back into plane so that they meet again. Depending on the tear this is usually possible to achieve but if serious distortion has occurred it may be necessary to trim some canvas yarns. The areas most resilient to treatment are distortions at each end of the tear where maximum stress concentration has occurred. Placing the canvas locally under pressure using weights, heated spatula and moist blotting paper can usually achieve a reasonable result. Then the canvas can be repaired either by using adhesive or by sewing. Some recent papers have described this process in detail and made useful observations on best practice.16 The essential points are that the tear repair is restricted to the plane and level of the canvas and the immediate area of the tear, and that it provides a rigid structural joint, with the yarns aligned.17 Next, the lost paint is filled and retouched. Often very little paint has been lost and the most extensive part of the retouching intervention is in disguising the more extensive cracking that has occurred around the tear.

Flaking paint

Lining a canvas was once thought to be a valid treatment to consolidate flaking paint. Most paint loss or flaking is caused by poor adhesion between the ground and canvas. Occasionally, due to bad artist’s technique, flaking can occur between paint films. As with other aspects of poor technique this is the most difficult type to deal with, but fortunately relatively rare.

However, the usual problem is the need to re-attach an original lean white-lead oil ground to a sized canvas. Because the dimensions and mass of each lifting and potentially flaking piece of paint/ground is small, Newton’s law tells us that the forces needed to re-attach them are very small. Indeed, I have seen small raised edges of paint that have escaped the conservator’s attention remain very stable for years despite having been exposed to constant handling and display. The demands on the adhesive are very small, and as we know even wax/resin is enough to hold an isolated area of paint. It is not surprising then that a multitude of adhesives has been suggested for consolidation and lining and not surprising that there is no consensus on the best one.

Perhaps the best adhesive is the most stable one. In conservation treatments we argue for reversibility but a truly reversible adhesive or consolidant is by definition not possible.

Our model of a canvas painting tells us that the canvas tension may well be carried principally in the size and ground, depending on the humidity, except at discontinuities (cracks) where the load is entirely carried by the canvas. This is a mechanism that leads to cupping and flaking of paint/ground and recent work at the Canadian Conservation Institute suggests that drying of the paint layers may also contribute to cupping. To counteract cupping, an adhesive with an elastic modulus at least as high as that of a lean ground would be needed. Such a structural adhesive would not be removable. We need to decide whether we wish simply to re-attach the canvas or be much more ambitious and reverse some of the effects of cracking. The latter approach still needs much more research and is I think the outstanding issue yet to be addressed – so we must be content with re-attachment.

If we accept this limited objective I think we should not worry too much about the nature of the adhesive we choose – after all it has to form a bond to dried oil, pigment, canvas and rabbit-skin glue, very different materials. This diversity of surface energy is part of the reason the original paint failed. The consolidating adhesive needs to have broad properties. That is why various commentators have justified vastly different adhesives from fish glue through synthetic emulsions to waxes.

Prevention

Much of a museum collection of contemporary art should be in good condition but we can be confident that it will deteriorate in a similar way to existing works in the historic collection. In many cases artists are still using stretched canvas to paint on and oil priming has only very recently been replaced by acrylic. There are differences in degree but the structures remain similar. However we can predict that when certain difficult works eventually need to be treated future conservators will have serious or insurmountable problems. We should therefore take action now to prevent or retard deterioration.

Most museums put much emphasis on preventive measures, reducing risks in handling, transport, display and storage. This has been the mainstay of the approach at Tate. By introducing procedures for the physical protection of works of art and restricting direct access to works of art we can avoid much accidental damage. By improving gallery environmental conditions and air quality we can reduce physical and chemical changes.

Framing policy has proved extremely effective in the past 30 years.18 The application of backboards, the strengthening of frames to ensure rigidity and the application of low reflecting glass whenever possible provides effective mechanical protection and ensures a microclimate around each work, which is far more stable than the best air-conditioning system. The extensive use of carrying/transit frames, wrapped in polythene, for handling, storage and lorry transport is also a mainstay. Such procedures are essential, particularly when our collection is used so heavily.

We also prioritise the examination and treatment of newly acquired works of art, putting them into a condition that pre-empts some of the deterioration effects that we predict. By surveying the collection we have identified those works already in the collection that need treatment. In the past many of these would have been prime candidates for lining but now we look for alternatives.

Double canvases (loose-lining)

In the nineteenth century several London colourmen sold double canvases, for example W. Brown of Holborn and later, Robersons and Winsor and Newton. Double canvases were regarded as a superior product and were bought by major artists. Many later paintings by J.M.W. Turner were painted on Brown’s double canvases and other established artists such as W.P. Frith, Sir Edwin Landseer, J.E.Millais and W.Holman Hunt also used double canvases.

These double canvases normally consist of a tightly woven heavy Ulster linen canvas, sized with rabbit-skin glue and primed with a lean oil ground. The ground is usually pigmented a dull white using a mixture of lead white and chalk applied by brush in at least two layers. It is applied evenly and smoothly, as would be expected from a commercial product. Large pieces of stretched canvas were pre-primed in this way for both single and double canvas systems.

When the ground has dried, the first canvas is stretched on a substantial expandable wooden stretcher with the ground facing the stretcher. Zinc coated iron tacks are normally used. This became the auxiliary canvas. The second canvas is stretched on the same stretcher, this time in the conventional way with the ground to the front, again using tacks. This became the primary canvas for painting on. The intention was to create a sandwich structure of ground, sized canvas, sized canvas, and ground. There is no adhesive between the two canvases, which are simply held together by the stretching process.

A variation on this method was the use of an un-primed canvas behind the main canvas rather than a primed one. This was cheaper and no doubt not considered as good.

Examination of the primed double canvases in the late twentieth century when they were about 150 years old revealed that the auxiliary canvas grounds had cracked with an almost identical pattern to the primary painted canvas ground (fig.4). They had cracked extensively to form a complete network of largely random cracks, which had then opened and allowed the paint to cup. The moisture response of the tightly woven linen and the thickness of the ground were the chief contributions to this.

Fig.5

A conservator attaches a strip-lining to the edges of a canvas

© Tate

When these supports were dismantled, removal of the primary canvas revealed the reverse which was free of dust and appeared to be relatively well preserved. Similarly, the auxiliary canvas was well preserved. So this was an effective system of preserving the canvas from the effects of pollution, both particulate and acid gas, which was principally sulphur dioxide in the period in question.

However this double canvas system (sometimes called an original loose-lining) did not prevent cracking and cupping of the ground and paint, nor did it prevent corner draws and loss of tension. Many of these paintings were relined in the 1960s, usually in an attempt to flatten disturbing cupping and undulations. Indeed, the auxiliary canvases were very useful objects on which to practise the flattening of cupping.

The valuable experience of one hundred and fifty years of aging revealed by these canvases encouraged conservators at Tate to use modern loose-linings on more recently painted works, as a preventive measure, and also for older paintings that we did not wish to line. The barrier effect of the original double canvases against dirt and pollution was clear but their failure to prevent the effects of canvas relaxation was also evident. Rather than use linen canvas for modern loose-linings we chose to use polyester sailcloth. This material is a fine, even polyester yarn which has been tightly woven, followed by heat treatment to shrink the canvas and lock the weave in place. When used as a sail it is designed to be impervious to wind and therefore it can significantly reduce the transport of air to the canvas reverse, keeping out all particulate and most gaseous pollution. The material is not expected to relax or creep to the same extent as canvas and acts to keep the stretcher in plane. I have a polyester canvas that I stretched twenty five years ago which is still very tight. It ought to provide an excellent support.

When a painted canvas is stretched on top of a polyester loose-lining its weight is supported by the polyester and it need not be stretched so tightly. It will look and feel tight even though only a small force has been exerted. This is a very important effect, which prevents, or at least reduces, the long-term relaxation that would otherwise occur with a tightly stretched linen canvas, even though this may not manifest itself for fifty years.

One drawback with a polyester loose-lining is that the reverse of the canvas becomes invisible and the polyester may even be taken for the original. If further work needs to be done to a painting at a later date the loose-lining may need to be removed. An advantage is that the original stretcher can be retained and preserved by this system and the total weight is only increased a very small amount.

A rigid support

When the stretcher is inadequate, as with many large modern works, and has to be replaced, the museum conservator may devise an entirely new support system that offers rigidity and protection from the rear. In a museum the extra weight is not such a problem and can even be an advantage. But replacing the support with a more rigid structure is a major aesthetic intervention, changing the nature of the stretched canvas. Not everyone agrees with such a change, although I would argue that it is valid provided it is not discernable from the front when the painting is on display.

A rigid support can be constructed from an aluminium honeycomb panel of the type used in aircraft manufacture. These are typically 25 mm or 50 mm thick, very light and rigid. By gouging out a small piece of the honeycomb at the edges a shaped piece of softwood can be inserted all the way round. This provides an edge that can take tacks or staples. It is then possible to stretch a canvas over the panel and attach it as on a stretcher. Like a loose-lining the panel provides support and allows much less tension to be used. A piece of paper is usually attached to the front of the panel to isolate it from the back of the canvas and also to provide friction. Being completely impermeable to moisture, the panel ensures stable conditions exist between it and the canvas. Being rigid, it provides a stable tension and protection from impacts from the reverse. Physically, it is the ideal support and readily reversible.

There are limits to the dimensions of individual panels but they can be joined indefinitely to make larger panels. Very large panels are heavy and difficult to lift unless handles are built in. A panel cannot be keyed out, but I think this is a fairly minor limitation, since it is possible to stretch a canvas adequately without keying out. If the canvas has not been stretched enough it should be re-stretched. It can then be left alone. In future if there is relaxation of the canvas it can also be re-stretched but the relaxation will be kept to a minimum by the original low tension and the absence of repeated keying out. However, a panel does alter the appearance of the canvas painting from the reverse and changes its character fundamentally.

Blind stretchers

Blind stretchers with panels inserted between the members have a history longer than double canvases. Some of these objects are beautifully constructed and they combine the advantages of the stretcher and the panel. But they do not appear to prevent cracking and the repeated keying out that is possible contributes to cracking and corner draws.

Stretcher bar lining

Many paintings are wanted for exhibition and loan. They need to travel, to be handled and perhaps to be exposed to different environmental conditions. A technique devised at Tate is called stretcher bar lining (previously known as a cami-lining in some literature).19 This involves using polyester sailcloth to provide a support, but in this case attaching the polyester to the reverse of the stretcher using staples along the reverse of the outside members and feeding the polyester under the stretcher cross-members to create a tensioned structure in which the lining is in contact or near contact with the original only at one point in the middle of the canvas. Tensioning the stretcher in this way produces a very rigid structure and the conservator needs to be careful not to pull too hard and remove or distort the tension in the original canvas.

The main value of this technique may not be immediately apparent but when the canvas is vibrated it becomes clear. Most old cracked paintings have cracks corresponding to the stretcher inside edges, in part attributed to the flapping of the canvas against the stretcher. Loss of tension, through relaxation (or creep), may play a role in this cracking as does the hygroscopic effect of the stretcher. But when a painting travels it is subject to repeated forced vibrations at a level and frequency that is close to its resonance, which will fall in a range of 10–20 Hertz. By preventing any movement at the middle of the painting the natural frequency is raised to about four times its original frequency, usually clear of the main input from a vehicle. The stretcher bar lining is applied continuously across the back of the canvas and the trapped air creates an air dam that absorbs the energy of vibration. The effect needs to be seen to be believed but it is very impressive.

Fig.6

A polyester sailcloth stretcher-bar lining stiffens the structure and prevents the canvas from vibrating in transit

© Tate

A great advantage of the stretcher bar lining is the speed with which it can be applied (fig.6). With practice it can be done in fifteen minutes and removed in five, depending on the number of staples. It is entirely reversible and preserves all aspects of the original stretching. We use it on many canvases to make them suitable for loan and transport and it normally remains in place for the next time the painting is moved.

De-lining

Removing an old glue lining is not without its risks and is very time consuming. We do it very infrequently, not least because it begs the question, what should we replace it with? If we consider that the lining was not necessary then the prospect of returning the painting to an unlined state is enticing, but it may be difficult to assess just how good a state the original canvas is in.

For paintings that have suffered serious lining damage in the past we might like the idea of reversing the damage. We can take off an old lining but it is unlikely that we can repair flattened impasto or emphasised canvas weave. If the lining is stable we should accept that it has become part of the object’s history. If the lining tacking edges are beginning to fail, we can remove the canvas and glue for about 25mm width around the perimeter of the canvas and strip-line the lined painting.

De-acidification

Most of the treatments discussed so far are physical interventions, but we must not forget that the deterioration of cellulose is predominantly a chemical process.20 Essentially, in the light cellulose is oxidised by air and in the dark it is hydrolysed by water vapour. The oxidation process creates acid groups that lower the pH of the canvas creating ideal conditions for hydrolysis. Air pollution also creates acid conditions. Our early attempts to reduce oxidation with anti-oxidants were not successful but the application of alkaline materials to increase pH was very successful, drastically reducing the rate of hydrolysis.

We have been tentatively de-acidifying canvases now for about twenty years and have not found any un-surmountable disadvantages to this procedure.21 Several studies have sought to find problems and unwanted side effects, but as time goes by I am increasingly confident to recommend the process to others.22 In careful hands, the application of a de-acidification agent of the Wei T’O type (magnesium methoxy methylcarbonate in a volatile solvent) appears to be effective and safe.23 The process reduces the rate of deterioration of new canvas when excluded from light by an order of magnitude. This is a powerful argument for its application to all new canvases.

Older canvases are frequently degraded and have absorbed much sulphur dioxide and other air pollution. Certain fibres such as hemp and sisal deteriorate very rapidly and become very acid. Surface pH measurements between 3 and 4 are common. These canvases should be at least neutralised to stop further rapid decay. Leaving an alkaline reserve of magnesium ions can provide a period of respite before the process accelerates again.

We are also beginning to go back to the oxidation problem. We are currently testing enclosures for works of art on paper that will be air-tight and will allow us to exclude oxygen. If this is successful it could be extended to some painting canvases.

Conclusion

Now that paintings are rarely lined it is difficult for a conservator to obtain practical experience of different types of lining. This means that the current generation may have to make decisions based on published studies, which may not give enough information to establish a balanced account of the benefits and disadvantages. Practical studies are likely to include the perceptions and pre-occupations of the conservators reporting on their work. Detached scientific studies of lining processes may not be able to take into account the full nature and range of the paintings that are under consideration. It is important to look at all the literature and not to come to conclusions too quickly about one solution or another, and to retain a range of possibilities for action.

Conservators have only a few reliable solutions to the complex structural problems that occur on paintings on canvas. In the past we have responded too late and too heavy-handedly to structural deterioration, sometimes creating more problems than we have solved. In the last thirty years we have seen a revolution in our understanding and have adopted methods that are far more considered and less interventionist.

Improved understanding of paintings on canvas has given us new ways of assessing the effectiveness of any treatment, but it does not prevent the need for ethical decisions. To help decide in a particular case, we can define a number of hierarchies: the degree of intervention that is acceptable, the likely success of any treatment and the seriousness of any negative side effects. These are dependent on the use to which our painting is to be put and the environment to which it will be exposed.

In general, we should like to preserve the nature of the object, the artists’ techniques and the original technology, but we need to make sure that the painted image is presented well and that the painting can be displayed, loaned and stored safely. We do not want to have to return to carry out further consolidation, although with under-bound paintings this is frequently the case. Increased confidence in the outcome of treatments means that we are willing to intervene less. Confidence in the behaviour and impact of the environment is also critical: for instance, creating a micro-environment around a painting within a glazed frame is so successful that even wood panels do not flake.

In a conservation timescale the changes in our understanding have been rapid and dramatic. Ideas have changed much more rapidly than our individual conservation treatments last. We have gone from a position of skilful but unthinking practice to one of much better knowledge.

As a result of this new knowledge in some areas we need to reconsider our ethics, many of which have been superseded by events. More subtle solutions are now available and we can analyse the forces and reactions involved. But our solutions are only as good as the accuracy of our predictions. In particular, our ability to intervene chemically and the implication that this is best done while the canvas retains some strength challenges the simple notion of minimalism.