Fig.1

Garden pathway, Broughton House

Author’s photograph

From the 1900s through to the 1920s, the Scots painter Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864–1933) turned increasingly to the cultivation of his antiquarian collection of local literature; folklore, poetry and history; and his walled garden by the banks of the river Dee in the Scottish Border town of Kirkcudbright. Hornel’s one acre garden was designed in sections (some were already in existence): areas of lawn, rose-beds and box hedges, flower and herb gardens (fig.1). But the section deemed most important to the artist himself was, as Stephen Harvey writing for Scottish Field in the 1970s termed it, ‘An Eastern Garden. This was clearly the artist’s own dominion, a place apart from the conventional villa garden, landscaped with exotics to remind Hornel of his travels. It was planted with pink Japanese wind flowers, with flagged paths meandering between clumps of golden maple, Japanese dwarf pines, a lily pond with stepping stones watched over by a lead flamingo, a grove of flowering cherry trees, a magnolia’1 (fig.2).

Fig.2

Pond and stepping stones, Broughton House

Author’s photograph

All of these derive from mid to late nineteenth-century japonaiserie, but around that collection of oriental plants and accessories, such as stone lanterns, were gathered relics of local origin; meal querns, curling stones, a tiny stone trough (actually an ancient coffin for a young child), an eleventh- or twelfth-century wayside cross from nearby Dalshangan village and a collection of stones, some decorative or inscribed, purloined from the ruins of nearby Dundrennan Abbey (figs.3 and 4). This favoured section of the garden, this place apart, is in one sense bricolage: objects appropriated, removed, relocated and assigned new meanings. So how might we interpret this ‘Japanese-Scottish’ garden? How might we understand the interrelations here between forms of painting, print-making, illustration and garden design, and what relation might these have to issues of cultural and national identity?

Fig.3

Dalshangan Cross, Broughton House

Author’s photograph

Fig.4

Stones in pathway, Broughton House

Author’s photograph

A native of Kirkcudbright,2 Hornel began work on his garden shortly after his purchase in 1901 of the rather grand eighteenth-century Broughton House on the High Street (fig.5). Having grown up in that street in more modest accommodation, he acquired ‘Bro-Hoose’ at the peak of his professional career. My contention here is that the aesthetic principles and cultural preoccupations that informed the design of his garden, extend those of his artistic practice from the late 1880s. As, from 1901, his paintings declined steadily into repetition and cliché and were no longer a focus for his originality, real stimulus came from the creation of an alternative space – the artist’s garden which we might regard as the material embodiment of an imagined arcadia over which he could exert his omnipotence and cultivate his memories. In acquiring and arranging his plant specimens, just as he accumulated and extended his collection of rare books, the artist projected his ideal identity, his cultural and aesthetic preferences.

Fig.5

Broughton House

Author’s photograph

After an unsatisfactory period at Edinburgh art school from 1880 to 1883, as Bill Smith’s excellent monograph on the artist relates, Hornel trained for two years under Charles Verlat at the Antwerp Academy. This, like the Académie Julian in Paris, was an important focus for many British students who were disaffected by academic teaching in both England and Scotland and were soon drawn to forms of rustic naturalism associated with French painters like Jules Bastien-Lepage and Jean-François Millet (see fig.6). But Hornel’s trajectory through the late 1880s and early 1890s was away from the naturalism we associate with representations of workers in the field towards a more decorative aesthetic as, with his associates the Glasgow Boys (James Guthrie, E.A. Walton and Joseph Crawhall) and especially his close working companion George Henry, he was increasingly exposed to new sources, from Whistler, to Adolphe Monticelli and Japanese wood-block prints, particularly through the influence of his Glasgow dealer, Alexander Reid.3 Impressionism, however, had little impact on Hornel. So whereas a one-time naturalist like Guthrie soon departed from ‘kail-yard’ paintings for the depiction of polite middle-class garden tea parties in Helensburgh with a loose, atmospheric handling (fig.7), Hornel rejected modern leisure scenes of the type associated with Impressionism. His preferred theme of young girls cavorting in dense thickets of nature relates rather more to John Singer Sargent’s painting Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose of 1885 (fig.8) but there are significant differences. Sargent’s scene of children in a Worcestershire garden be-decked with fashionable Chinese lanterns is, fundamentally, a painting of modern life, finely balanced between Aestheticism and Impressionism.4

Fig.7

James Guthrie

Midsummer 1892

Royal Scottish Academy (Diploma Collection), Edinburgh

Fig.6

E. A. Hornel

In the Town Crofts, Kirkcudbright 1885

Private collection

John Singer Sargent

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1885–6)

Tate

Hornel was drawn, instead, to visionary evocations of a universal timelessness: his children are at one with the rhythms of the natural world. His impasto technique and intense colour increasingly demonstrated the influence of late Pre-Raphaelitism, of Rossetti’s idyllic, fragrant bowers, and more specifically of the French Provençal painter Adolphe Monticelli whose works, shown in Edinburgh in 1886, conjured at that time, ‘an enchanted garden’ in which we might ‘breathe airs blown as from heavy laden flowers’.5 Monticelli’s paintings, like Fête dans le jardin, with their mosaic-like brushwork and impenetrable surfaces, suggested to Hornel a discrete and magical world, one only conceivable once superficial appearances were disrupted, conventional perspective discarded and, increasingly for him, naturalism eschewed.6 Ideal unity and coherence was to be established uniquely within the distinct confines of the picture plane and, later, in the artist’s own garden.7

Hornel’s paintings celebrated a Galloway that was magic and exotic, a disposition that was widely shared by the close of the nineteenth century. His own fascination for the local folklore was first revealed in his illustrations to Malcolm Harper’s Bards of Galloway of 1889, a collection of the legend and poetry of a region deemed well fitted to the ‘poet’s eye and heart’, with its ‘poetic superstitions’, ‘picturesque glens’ ‘and the venerable relics of antiquity with which its villages are studded’.8 But Harper’s closing lament is very familiar: ‘cheap literature, railways, telegraphs, the bustle and hurry of commerce, a refinement of life and manners, all mean that the old customs of the country are fast disappearing’. Fairies are no longer believed in and ‘the romance has disappeared’. The ‘essence’ of place and character lies in the past.

Hornel and Henry’s The Druids bringing in the Mistletoe 1890 (fig.9) responded to Harper with an expression of the mystery, the primitive simplicity of the county and with evident interest in the remnants of its Celtic past and sacred customs.9 (Hornel was a member of the local Field Naturalists and Antiquarian Society’, often apparently leading its members away from the study of birds and butterflies for tours of the surrounding Kirkcudbright countryside in search of ancient standing stones and cup and ring marks). The compressed picture space in The Druids, the symbolic motifs, gold leaf, and the decorative robes demonstrate a knowledge of Celtic artistic practice and reveal, for John Morrison, that Henry and Hornel were in the vanguard of the Celtic Revival movement that sought to ‘trace the true origins of Scots and Scottish culture and to develop a language, both formal and iconographic that could serve as an archetype for Scottish art’.10 But that flattened perspective and asymmetrical composition also suggest the influence of Japanese prints. Hornel (like Harper) dismissed material reality for evocations of an ancient local culture but drew on certain formal qualities of the Japanese print to emphasise those distinctions. And these allusions to an ancient Scottish past, via characteristics of both Monticelli and Japonisme, all signified, to him, fantasy and a world of enchantment. While, as Lindsay Errington suggested, after The Druids Hornel and Henry no longer pursued the Celtic revival directly in their subject matter, following Japonisme instead, both of these idealised aesthetic traditions, it seems to me, manifest themselves in Hornel’s Kirkcudbright garden.11

Fig.9

E. A. Hornel and George Henry

The Druids Bringing in the Mistletoe 1890

Glasgow Museums: Art Gallery and Museum, Kelvingrove.

The supposedly unique characteristics of Celtic culture and the Celtic temperament continued to inform his practice, but more obliquely. Hence his interest and that of his close friend Charles Mackie and dealer Reid in the decorative synthetism, the rhythmic design of Nabis painters like Paul Sérusier for whom the ‘celticity’ of Brittany was crucial.12 In The Studio magazine’s 1895 account of ‘Concarneau as a Sketching Ground’, Brittany was described as a place where ‘Druidical remains abound and help to keep alive the old fables and traditions so dear to this poetic race’.13 From the mid-nineteenth century the Celts were ‘variously constructed as a figure of otherness, irrational, magical, non-scientific, emotional’ and often, as Malcolm Chapman pointed out, ‘regarded as a healthy alternative to western rationality’.14 In Hornel a new formal language of high horizons, steep foregrounds and snaking arabesques was claimed for this re-discovered culture in works such as The Dance of Spring 1891 (fig.10), which, to the critic D. S. MacColl, demonstrated an ability to ‘make an image out of [nature] and bring in the element of strangeness … Messrs Henry and Hornel give us pastorals from Ayrshire, but they are also pastorals from Wonderland’.15

Fig.10

E. A. Hornel, The Dance of Spring 1891

Glasgow Museums: Art Gallery and Museum, Kelvingrove

At the same time, Pont-Aven synthetists along with van Gogh and Hornel would have concurred with accounts in publications like Siegfried Bing’s journal of the late 1880s, Artistic Japan, of the Japanese artist as one instinctively attuned to the natural world, one who, as in an article by Ary Renan on Hokusai, perceives, ‘The world [as] a great garden in which he plays in innocence, making charming posies and watching the flight of the butterfly’.16

Hornel’s exposure to aesthetic doctrines like these ultimately shaped his aesthetic geography. His conceptions of Galloway, like Sérusier’s of Brittany and Van Gogh’s of Provence are analogous to idealised western views of Japan. In February 1893 he and Henry, funded by Reid, set sail for Japan. But Hornel’s perceptions and prejudices – later revealed in his lecture to a Glasgow audience – oscillated between rapture and regret. He remembers the country as a lotus land, its people ‘as a large and happy family, clattering along in the sunshine with smiling faces to spend the day ‘mid plum or cherry blossom’. Yet ‘the revolution of 1668’, he declared, ‘swept away for ever the old Japan with its poetry and romance, investing the country with the habits and practices of Birmingham’.17 In common with other artist visitors such as Mortimer Menpes and Alfred East, he appreciated the Japanese reverence for nature (‘Nature to them is symbolism itself’) and their festival times (‘the whole earth [rejoices] in a profusion of bloom’) but what emerged most powerfully from this account was an obsession with good and bad taste, with charm and vulgarity – the charm and perfect taste displayed in Japanese flower arranging, the vulgarity and bad taste of the West. Hornel hankered after the ‘highest ideals of the Feudal Jap of old time’, for the present day merchant classes are ‘liars and untrustworthy’. This class and cultural snobbery extended to his perceptions of Japanese gardens. He admired the ‘gardens of the wealthy and upper classes where miniature lakes and waterfalls with quaint bridges, tiny landscapes with dwarf pines and shrubs relieved with stone lanterns, take you into fairyland’.

To Hornel the Japanese aesthetic was ‘the greatest impressionism the world has so far possessed – all useless details are laid aside’, ‘whereas we have been working too much on the surface, and in striving to realise Truth have forgotten the spirit’.18 Naturalism, in this context, is aesthetically vulgar as, in 1901, Mortimer Menpes confirmed, ‘The sense of perfect placing . All Orientals are more or less possessed of this intuitive sense of balance even the ‘common man’ has acquired the scientific placing of his things the feeling permeates all classes’.19 But whereas Hornel compared the Japanese favourably to the European, Menpes addressed himself to the English: ‘Japan might be said to be as artistic as England is inartistic’. He retold one man’s account of nature as observed in Surrey: ‘I never saw the lines of a bush pick up those of a fence with one broad sweep. Nature never behaved like that in Dorking.’ Nor he argued, did she in Japan, ‘but the Japanese realise that Nature is an instrument with harmonies to be coaxed out .We want parks and stags and moorlands, broad expanses of country and huge avenues, while the Japanese will be content with one exquisite little harmony’. The central preoccupation here is with issues of taste and anxieties about shifting class boundaries; national identity is, perhaps, a red herring. To extend the metaphor of gardening, ‘cultivation’ in both its horticultural and wider cultural contexts expressed symbolic distinction. For Menpes, ‘Nothing disturbs in a Japanese landscape. It is the harmonic combination of untouched naturalness and high artistic cultivation’.20

Fig.11

E. A. Hornel, A Japanese Garden 1894

Sheila MacNicol

Hornel’s first thirteen-month trip to Japan (he went back in the 1920s) was an exercise in pursuing scenes of picturesque authenticity and avoiding or editing out the aesthetically undesirable – evidence of Japanese modernity. For the most part, as Bill Smith records, the artists remained in the area around the treaty ports of Tokyo and Yokohama, sketching in parks and tea gardens that were later used in compositions like A Japanese Garden, 1894 (fig.11). Ayako Ono has demonstrated the extent to which these compositions were closely reliant on albums of hand-tinted prints created specifically for tourists, depicting geishas in tea ceremonies, dancing or posing in gardens amongst the chrysanthemums.21 As with earlier Galloway compositions, the artist here mingles certain elements of the Japanese print, a use of perspective in particular, with much denser brushwork, brilliant colour and a more intense, all-over decorative quality still derived from Monticelli. Although his pictures draw inspiration from a supposedly Japanese attitude to nature, they share little of a formal, compositional approach.

Hornel’s forty-four Japanese pictures were a sell-out (save for one) at Reid’s Glasgow gallery La Société des Beaux-Arts in April 1895. The reviews scrapbook kept at Broughton House contains notices from the Glasgow press comparing him favourably with painters like Alfred East and Alfred Parsons who also visited Japan around this period but who were content to be pretty in an ‘Anglo-Japanese way [whereas Hornel] has brought to the Orient two singularly strong natural qualities – a Celtic passion for romance, and a revelling sense of colour’.22 In 1908 James Caw’s Scottish Painting Past and Present contrasted the paintings with the restrained art of Japan: ‘The colour was as enchanting as an Arabian Night’s tale, as brilliant as a parrot house, as varied as a flower-garden.’23 It was through qualities such as these, Richard Muther was also to confirm, that ‘the Scotch nourished the modern longing for mystical worlds of beauty’.24

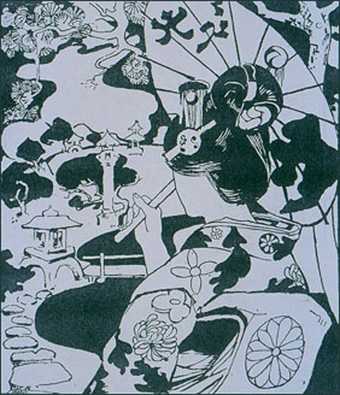

Fig.12

E. A. Hornel, Madame Chrysanthème in The Evergreen

All of the national and cultural stereotypes considered so far – of Scottish art as innately decorative and unworldly, of the Japanese artist in an essential harmony with nature and of a Pan-Celticism (intuitive, romantic, spiritual) that extended beyond Scotland to a special identification with Pont Aven synthetistes – culminate in interesting ways in the Scots naturalist and city planner Patrick Geddes’s short-lived journal The Evergreen published in Edinburgh between 1895–6.25 This contained illustrations of Breton subjects by the Scots artist Robert Brough, of Celtic heroines and heroes by the Scots symbolist John Duncan, of dancing girls in gardens and natural landscapes by Charles Mackie, who also designed the ‘Tree of Life’ cover for the journal. Hornel himself made an appearance in the second issue, The Book of Autumn, in 1895, with a line drawing of a Japanese geisha gazing across an ornamental garden (fig.12) Its title, Madame Chrysanthème, refers to Pierre Loti’s influential novel of 1888, which did much to inform the view of European artists like Van Gogh of Japan as a simple, organic, primitive country. Hornel’s Japanese lecture had described the rhythm of the seasons there, of flowers after flowers, all culminating in the ‘regal and imperial chrysanthemum’, emphasising (as did Geddes) the fundamental importance of the cycle of nature. For Geddes himself, in that same issue, ‘the seasons determine labour, the family and the very structure of society, posing a problem for the ‘modern Troglodytes’ in their ‘smoky labyrinths’ in the city. The intuitive artist’s role in all of this is simply to perfect his ‘fantasias of reveries’. ‘Our new Merlins’, he wrote, ‘thus brighten our winter with their gardens of dream.’ In the artist’s perception of the progress of the seasons – from the seasonal decay of rotting compost to the growing seed of a new life – lay the regeneration of the ‘Individual and of the Race’. In his biological mysticism Geddes was continually intent on a unity of art and science, of which gardening was a prime example. ‘Il faut cultiver son jardin’ he declares – inevitably, perhaps.26 This was exactly what Hornel was poised to do.

Edward Atkinson Hornel

Autumn (1904)

Tate

Shortly after the success of his Japanese exhibition, Hornel reverted to depictions of Galloway children in nature, for example, In the Orchard (City Art Gallery, Edinburgh) or Tate’s Autumn, 1904 (fig.13). However, he maintained the same picturesque low viewpoints and animated surfaces that intertwine the local girls within the blossoming orchard and garden scenery. The physical space his Japanese garden occupied is small and densely planted with, as a result, a claustrophobic quality. There is no possibility here of a bird’s eye view or a commanding perspective. To stand back is to risk falling into the lily pond or the stream (fig.14). The experience of actually being in the garden, surrounded by dense foliage, is rather like that of looking at one of Hornel’s low perspective paintings of garden motifs. The only missing ingredient in this magical, self-sufficient world is that self-absorbed group of young girls. And that eschewal of distance in the painting, matches the artist’s own growing absorption in his local social space, increasingly divorced from the wider art world.

From this point Hornel photographed his models in the specially designed studio at Broughton House, later filling in the backgrounds with studies of foliage from the garden or settings from local woodland or nearby Brighouse Bay. His palette became steadily less vibrant and the works have little of the rhythmic vitality of those from the late 1880s and 1890s. As the relationship with Alexander Reid came to an end around 1909, Hornel devoted more attention to his house and garden and increasingly became a leading, paternalist figure about the town. So when E. Rimbault Dibdin came to Kirkcudbright to write about Hornel’s ‘Paintings of Children and Flowers’ for The Studio in 1907, he described first the artist’s ‘fine old house’, ‘set in a large old garden’, and noticed that, ‘All about his doors are the children of the poor, [many his red-headed young models]. His garden is full of flowers, and the flowers of humanity are free to come in from the street [through the side gate] and enjoy themselves in it. He meanwhile studies and paints them, the flowers and the children, in the open air’.27 Geddes’s Merlin perhaps in his garden of dream?

Fig.14

Pond and yucca, Broughton House

Author’s photograph

The dream, of course, was not conjured from the air but from continual research and planning. Hornel’s library contains an interesting array of titles from around 1907–12. In among works on Japanese art, such as Laurence Binyon’s The Flight of the Dragon (1911) and local archaeological texts, such as Druidism Exhumed, are copies of seed catalogues from the Yokahama nursery: titles like Lilies of Japan, Japanese Species of Bamboo, books on iris and peony cultivation, plus an album of 95 Photographs of Japanese Tea Rooms and Gardens. Up to 1910 at least there were successive publications of manuals and ‘how to’ books on Japanese garden design for the European market. The most significant and scholarly perhaps was the architect and renowned Japoniste, Josiah Conder’s Landscape Gardening in Japan, first published in 1892. As Azby Brown comments, coupled with the photographs of particular types of garden, such as tea gardens (‘with the character of wildness and sequestered solitude’), stone gardens, imperial gardens and so on, Conder’s book contained enough information to enable a designer in the West to create a replica.28

As Brown suggests, Conder is at core an Orientalist, ‘interpreting an Asian culture, even packaging it for consumption on behalf of Westerners who might like to partake of its perceived exoticism without directly engaging its people’.29 Conder’s primary concern in his preface was to clarify the abstract aesthetic principles of the Japanese garden which lay beneath their ‘quaint and unfamiliar aspect’ and which might, he believed, be applied to the gardens of any country. The contrast with the rigid symmetry of the European formal garden was also perhaps part of the appeal of Japanese gardens, which were deemed pictorial rather than architectural, although in neither form, as an article in The Times in 1910 pointed out, was ‘nature allowed to have her way’.30

The ‘impression of fantastic unreality’, Conder argued, which Japanese garden designs produced on the minds of Westerners was the result of the refusal of naturalism, also found in Japanese art. In both landscape painting and garden design, nature was represented, not reproduced. Leading characteristics were selected and accentuated so as to combine ‘a mood of nature and also a mood of man’. A garden should be designed ‘to suggest a suitable idea and arouse definite pleasurable associations’, the ideal Japanese garden being, therefore, ‘a retreat for secluded ease and meditation’.

Underlying order derived from the careful placement of plants; scale and proportion were also crucial. This explains the siting next to the stream and stepping stones in Hornel’s garden of a once carefully pruned example of ‘cloud’ topiary, now an overgrown conifer destined to be cut down. The stream itself, now run dry, reveals pipe work relating to an original water feature in the nearby rocks. All of these elements, at one time, were positioned so as to suggest some ideal environment. Nature had to be coaxed to perfection by electric pumps and elementary plumbing. Conder demonstrated, too, the importance of stone garden lanterns, also required to harmonise with their surroundings and placed so that, once lit, their reddish light would reflect on water. He insisted on the metaphorical value of the particular shape and relationship of stones in the Japanese garden, often intended to suggest natural scenery. He also explained the influence of Buddhist priests from the twelfth century in the selection and grouping of standing-stones with imaginary and religious attributes. He described particular tea gardens with their extreme simplicity and affectation of natural wildness; their stone lanterns, water basins, rocks and gateways – characteristic features of Hornel’s own garden – all combined to produce an appearance of antiquity

But the Scots artist’s ‘Eastern garden’ represented his own ideal territory, and in substituting Japanese stones for those of ancient local origin, like the Dalshangan cross and stones from the nearby thirteenth century Dundrennan Abbey from where Mary Queen Scots made her ‘fatal decision’ to leave Scotland, he created iconographic references to his fantasy of place and of an historic, organic Scottish culture, free of conflict and as much in harmony with nature and the landscape as were the young girls he depicted in his paintings. An interesting absence in his library – one that speaks volumes – are books on contemporary labour issues and accounts of recent local and political concerns.31

Hornel’s success in cultivating and promoting a very particular regional and cultural identity – a place myth – and, as a result, in attracting visitors (artistic and otherwise) is evident still today. The local ‘artists’ town’ website and recent surveys suggests that ‘as Gauguin was a magnet to Pont Aven, so Hornel was to Kirkcudbright’. Increasingly after the turn of the century his deep attachment to place produced a particular home-, or, rather, garden-sickness. On his trip to Ceylon in 1907 he was disappointed that the colours did not meet his anticipations and the country was less exotic than he had imagined. Disenchanted, unable to reconcile expectations and actual experience, he is nostalgic for his own garden. The ‘going away’ simply intensified his idealisations, and he wrote: ‘I go home with double interest in my garden, from letters . my garden has been doing marvels. The Peonies were magnificent, & my Wisteria which I have longed for many weary years to see in bloom, took advantage of my absence and made a royal show.’32

Fig.15

E. A. Hornel’s garden

Photograph in Scottish Country Life 1916

On his return, as Smith records, Hornel showed annually at Royal Academy exhibitions, pictures which had become increasingly mechanical and repetitious, often just reversing images from other paintings.33 But steady financial rewards were enough to allow him to concentrate on house and garden. In 1916 the still new journal Scottish Country Life (which first appeared in 1914) visited Broughton House (fig.15), noting the old world picturesque atmosphere of the town and its ancient history. The entrancing ‘old world garden’ behind Hornel’s house reminded the author of Herrick’s bewitching ‘wild civility’, and he or she felt moved as ‘with the insistence of an old melody‘.34 Such a location was perfect material for that journal: it was ‘a treasury of art, impeccable taste, and irresistible effects; the external efflorescence of the soul of the painter whose joyous creations have profoundly enlarged the aesthetic vision of the race’. All of this was clearly aimed at a readership much concerned with matters of historic, Scottish tradition, with the cultivation of taste, with issues of preservation and conservation and drawn to nostalgic representations of historical harmony.

These, essentially, were Hornel’s own concerns. His collecting mania was accelerating as he acquired, in 1919, local publisher Thomas Fraser’s own library of books on Borders’ history and folklore to add to his own. At this point he apparently envisaged creating an art gallery and library alongside his garden to hand down to the local people of Kirkcudbright.35 But at the same time he continued his infatuation with Japan, still intent on recreating the impact of that first visit, still seeking enchantment and sensual gratification, and perhaps hoping to rekindle the vitality quite lost from his paintings. So he travelled via Burma to Japan again for six months in 1920 and painted gardens mostly in Kyoto, which he used as backgrounds in pictures, having been given a ‘gorgeous book’, as a memento and taken on a tour of the best local gardens by the son of Marquis Matsukata.

Nostalgia and memory became central themes of Hornel’s late work: indeed, Memories of Mandelay is the title of a large work still hanging inside Broughton House. For a visitor named Dorothy Burnie in 1925, the importance of memory, the transience of summer and of life was expressed metaphorically outside the house, too – in the garden, in the form of three old sundials ‘silent reminders of Time’. For Burnie, the house itself contained an unrivalled collection of the history and literature, the ‘folk-lore and romance of the storied land of Galloway’: it was ‘the veriest poem of art in nature‘.36 Such had been the ambition of the artist in his paintings, but it was perhaps outside, in his garden, that he was best able to create an ideal space, an ideal identity and cultural landscape.