Henry Moore and Stone: Methods and Materials

Sebastiano Barassi and James Copper

Moore never doubted the centrality of stone in his practice. This essay traces his approach to stone through different phases of his career, exploring his engagement with various types of it and the contexts, both physical and intellectual, in which he produced his carved works.

Many of Henry Moore’s retrospective accounts of his childhood and early influences include references to his fascination with stone in sculpture, architecture and the landscape. In the 1960s, for example, he recalled how it was on hearing, aged eleven, an anecdote about Michelangelo carving a stone head that he decided to become a sculptor;1 and he identified the carvings he saw during a school trip at Methley Church, near Castleford, as the first sculptures he remembered.2 In later years he also referred to the influence his childhood encounters with rocky formations in the Yorkshire landscape, such as Adel Rock, had had on him.3 Although these recollections were often coloured by a degree of post hoc reinterpretation, aimed at presenting a carefully controlled image of his artistic trajectory, there can be little doubt that stone played a crucial role in Moore’s art from the very beginning of his career, as both a material and visual source.

Henry Moore working on Three Way Piece Carving 1972

Henraux marble quarry

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Luigi Beggi, Henraux

Fig.1

Henry Moore working on Three Way Piece Carving 1972

Henraux marble quarry

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Luigi Beggi, Henraux

A lifelong fascination

Moore’s interest in stone sculpture started when he was still a student. When, aged twenty-three, he arrived in London to study at the Royal College of Art in 1921, he was already well aware of recent developments and debates around sculptural practice. Since the late nineteenth century the desire to abandon academicism and traditional vocabularies and to seek inspiration in non-classical and non-Western art had been a key element of artistic innovation. In sculpture, one of the most significant consequences of the move away from the dominant traditions had been the return to direct carving in stone and wood, which often dovetailed with a new attitude towards the treatment of materials. By the late 1910s modernist sculptors such as Constantin Brancusi, Jacob Epstein, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Amedeo Modigliani, and critics like Roger Fry whose writings played an important role in shaping Moore’s views early in his career, had already identified the practice of direct carving and the notion of ‘truth to materials’ as salient characteristics of avant-garde sculpture.

Soon after starting the course at the Royal College of Art Moore realised that the teaching of stone carving was viewed there merely as a technical exercise, essentially just a method for making copies from plaster and clay maquettes with the aid of the pointing machine. This, he thought, could not but result in ‘uninspired and dead’ work, as he later recalled.7 Reacting against this perceived lack of vitality, Moore developed views on the nature of a modern sculptural language which were largely aligned with those of the artists and critics he admired. Echoing them, he came to believe that ‘sculpture in stone should look like stone, hard and concentrated. To make stone look like flesh and blood, hair and dimples, is coming down to the level of the stage conjurer.’8

Like many of his contemporaries seeking new ideas and ways of working, Moore sought inspiration in non-Western artefacts. As a student he was offered access to the collections of Michael Sadler in Leeds and Charles Rutherston in London, and from 1921 he regularly visited the British Museum, which he later credited with having given him ‘nine-tenths’ of his understanding and learning about sculpture.9 In the museum’s collections Moore admired in particular the monumentality of Egyptian sculpture, the formal simplification of African and Pacific art and the sense of form of Cycladic sculpture. It was Mexican art, the ‘stoniest of all’, however, which made the biggest impression. Among the works which Moore singled out as the most inspiring were Egyptian limestone and basalt monuments, Cycladic marble figurines and Aztec basalt masks and figures.

Moore also studied European art outside the classical and neo-classical canons, showing a particular interest in Romanesque and Norman sculpture. Following his early encounter with the carvings at Methley, in the early 1920s he visited Chichester Cathedral, where he recalled being particularly impressed by two early twelfth-century Norman stone reliefs.10 One of the characteristics which all these sculptures shared, and which especially appealed to Moore, was their ‘stoniness’:

Mexican sculpture, as soon as I found it, seemed to me true and right, perhaps because I at once hit on similarities in it with some eleventh-century carvings I had seen as a boy in Yorkshire churches. Its ‘stoniness’, by which I mean its truth to material, its tremendous power without loss of sensitiveness, its astonishing variety and fertility of form-invention and its approach to a full three-dimensional conception of form, make it unsurpassed in my opinion by any other period of stone sculpture.11

Although Moore’s initial response to these works focused primarily on their formal qualities and their significance in the context of current theoretical debates, he was also clearly aware of the importance of acquiring an in-depth understanding of their material properties. Tellingly, he ascribed his dissatisfaction with some of his early carvings to both his sketchy knowledge of the stone he had used and an excessive reverence for the material – a ‘fear of ill-treating it’.12 In a letter to Jocelyn Horner written from Wighton in August 1923, he mentioned two alabaster carvings (Torso 1923 and Striding Torso 1923, both lost, presumed destroyed by the artist), commenting that he ‘didn’t find the ... forms suitable to the material’.13 Determined to overcome such critical gaps in his knowledge Moore visited frequently the Geological Museum in South Kensington (today part of the Natural History Museum), where he could study displays of stones from around the world.

Another consequence of the recent seismic shifts in sculpture practice that influenced Moore was the rejection of materials – above all, white marble – traditionally associated with what were widely perceived as hackneyed forms of classicism. Sculptors now favoured more unusual and colourful stones, often sourced from exotic parts of the world. Materials such as onyx, lapis-lazuli, sodolite, alabaster, serpentine and fossil marble, which until then had been mostly used for decorative objects, had a new appeal. In the Geological Museum (later part of the Natural History Museum) Moore had access to samples of all these stones and many more. However, he found himself mostly attracted to the displays of English stones, which included examples from, among others, the Hornton, Hopton Wood, Ancaster, Corsehill, Portland, Ham Hill and Mansfield quarries. Moore explained to the photographer Gemma Levine in 1978 the reasons behind his preference for English stone in the early part of his career: ‘I made a point of using native materials because I thought that, being English, I should understand our stones. They were cheaper, and I could go round to a stonemason and buy random pieces. I tried to use English stones that hadn’t been used before for sculpture.’14 Yet, in the London of the early 1920s these rarely-used stones were likely to be perceived as quite exotic. At that time they were still relatively unknown outside their areas of origin, because they had not been widely commercialised and historically they had been used as building materials in their locality, and only very exceptionally for sculpture. Using these stones gave Moore the opportunity both to appear original and innovative and to utilise materials that were relatively cheap and easy to source, two qualities which, as he pointed out, had great appeal for a young sculptor. Moreover, as curator Judith Collins suggested in 1998, Moore (and Barbara Hepworth with him) appreciated the anonymous qualities of these lesser-known stones because they were ‘more in keeping with the more anonymous mood of the work then being carved.’15 Moore’s preference for native woods such as beech, box, cherry, walnut and sycamore is likely to have been driven by similar concerns.

The English tradition

While it is evident that Moore’s interest in stone originated primarily in his commitment to direct carving, his use of native stones and his siting of works outdoors raise the question of the ‘Englishness’ of his art. In many ways Moore’s career-long exploration of the relationship of sculpture with the landscape belongs in a well-established strand of English culture, which has echoes in not only eighteenth- and nineteenth-century painting but also the prehistoric siting of monoliths in open spaces for what are thought to have been ritual purposes. In 1937 Moore stressed the importance of this outdoors aspect of his work, declaring that ‘a large piece of stone or wood placed almost anywhere at random in a field, orchard or garden, immediately looks right and inspiring.’16 His interest in Stonehenge as a subject (he considered it as much sculpture as architecture)17 and his fascination with standing stones and Gothic architecture (‘which forces the material as far as it will go’)18 suggest that Moore considered stone a key element of this tradition, and that he was eager to position himself within it.

The idea that his sculptures were made from native stone and were best seen in the English landscape from which the stone originated was based on a circularity of concept, almost an inevitability, which resonated with Moore’s more poetic side. In many ways, these processes of making stone works and displaying them in the landscape echo the cycles of nature and history that inspired Moore and particularly resonated with commentators after the Second World War. Jacquetta Hawkes remarked in her book A Land (1951): ‘Once when I was in Moore’s studio and saw one of his reclining figures with the shaft of a belemnite exposed in the thigh, my vision of this unity [of past and present, of mind and matter, of man and man’s origin] was overwhelming.’19 The asymmetry and unevenness of the stone’s mass, which soft materials such as clay and plaster lack, seems to have particularly appealed to Moore in part because they were the result of millenarian natural processes of stratification and erosion. Compared, for example, with the speed of modelling a small maquette, the slowness of stone carving seemed more attuned to the long cycles of nature. Moore’s engagement with and exploitation of these characteristics of stone (unevenness, asymmetry and slowness) also suggests that to a great extent he considered the material, or at least certain types of it, essentially anti-classical.

Just after the war Moore talked movingly about his feelings for the landscape in relation to his brown Hornton stone Memorial Figure 1945–6 (Dartington Hall Trust; fig.2):

The figure is a memorial to a friend [Christopher Martin] who loved the quiet mellowness of the Devonshire landscape. It is situated at the top of a rise and, when one stands near it, and takes in the shape of it in relation to the vista, one becomes aware that the raised knee repeats or echoes the gentle roll of the landscape. I wanted it to convey a sense of permanent tranquillity, a sense of being from which the stir and fret of human ways had been withdrawn, and all the time I was working on it I was very much aware that I was making a memorial to go into an English scene that is itself a memorial to many generations of men who have engaged in a subtle collaboration with the land.20

Memorial Figure is also a telling example of how Moore’s choice of stone for outdoor works was driven not only by his vision for the sculpture itself but also by the relationship with the permanent setting for which it was conceived.

By the time he made Memorial Figure Moore was already an established and widely recognised artist. His involvement with two of the leading artistic movements of 1930s Britain – constructivism and surrealism – had allowed him to develop a sophisticated new sculptural vocabulary. As the only English artist with a foot in both camps (which saw themselves in opposition to each other), Moore was freer than his peers to draw inspiration from a wide range of ideas. Thus, he could equally convincingly contextualise his use of stone in relationship to, on the one hand, Englishness and the native landscape and, on the other, constructivist methods and techniques; and he was ready to discuss the role of stone both in debates about the opposition of abstraction and realism and in relationship to the use of found objects in art.

One of Moore’s most significant contributions to artistic discussions of the interwar years was his use of pebbles and flints (as well as seashells and bones) as the starting point for new work. He began to collect stones around 1929, fascinated above all by the effects of the forces of nature on their raw material: ‘Pebbles and rocks show Nature’s way of working stone’, he famously wrote in 1934. ‘Smooth, sea-worn pebbles show the wearing away, rubbed treatment of stone and principles of asymmetry. Rocks show the hacked, hewn treatment of stone, and have a jagged nervous block rhythm.’21 During holidays at Happisburgh in Norfolk in the summers of 1930–1 Moore collected from the beach ironstone pebbles, which he later used to make small sculptures.22 Towards the end of the 1930s he made small carvings from chalk pebbles found under Shakespeare Cliff in Kent, and from these he later developed ideas for new sculptures (see, for example, Animal Head 1951). As Moore commented in 1937, the practice of collecting became almost a ritual, a way of regularly refreshing, or even rethinking his views on form:

Sometimes for several years running I have been to the same part of the sea-shore – but each year a new shape of pebble has caught my eye, which the year before, though it was there in hundreds, I never saw. Out of the millions of pebbles passed in walking along the shore, I choose out to see with excitement only those which fit in with my existing form-interest at the time. A different thing happens if I sit down and examine a handful one by one. I may then extend my form-experience more by giving my mind time to become conditioned to a new shape.23

Years later H.S. ‘Jim’ Ede, a friend of Moore’s and later the creator of Kettle’s Yard, used similar words to describe his own interest in pebbles, which had also begun in the 1920s and would later play a crucial role in the genesis of his Cambridge home.

Methods and materials

Moore’s understanding of stone was deeply informed by his views on the different nature of the processes of modelling and carving, in particular in the construction of sculptural space. Whereas with modelling the sculptor builds forms outwards, by addition, and therefore has potentially limitless space to expand into, ‘carving starts with a solid block which has surfaces but no space’, he commented in the mid-1950s. ‘To make complete three-dimensional form in carving, it is necessary, besides thinking of the outer surfaces of forms, to think of the centres of forms, so that they exist from INSIDE OUTWARDS.’24 Thus, the almost archaeological process of arriving at the ‘centre of form’ was partly determined by the surrounding material, which played an active role in shaping the sculpture, in ways that were inevitably very different from the process of modelling.

Henry Moore

Half Figure 1930

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Half Figure 1930

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

When I am asked by an architect to find or make a sculpture to go with his building I am never very excited about it. I know there will be problems. All architecture is geometric with dominating horizontal and vertical lines, and these are so insistent that if any asymmetrical sculpture is put with it you will find somewhere these distracting lines very evident in the background. In fact the building’s geometry is so insistent that to find a position far enough away for the sculpture to have its own scale or presence may be impossible.26

Henry Moore

Photograph showing Moore's Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–58 as originally sited in front of the Unesco building, Paris

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Photograph showing Moore's Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–58 as originally sited in front of the Unesco building, Paris

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore carving Divided Oval: Butterfly 1967 at the Henraux Marble Quarry, Querceta, Italy, 1966

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Ugo Mulas

Fig.5

Henry Moore carving Divided Oval: Butterfly 1967 at the Henraux Marble Quarry, Querceta, Italy, 1966

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Ugo Mulas

A relatively straightforward solution, which Moore adopted for one of the earliest of such commissions, was to use for the sculpture a material used for the building by which it would be sited. Thus, for Reclining Figure of 1957–8, commissioned for Unesco’s new Parisian headquarters, Moore decided to use travertine, a traditional building material that the architects Marcel Breuer, Pier Luigi Nervi and Bernard Zehrfuss had used in combination with modern materials such as concrete, glass and steel to suggest a dialogue between history and the present. By echoing the straight lines of the architecture in the natural horizontal patterns of the stone Moore sought a sense of unusual unity between his work and the setting for which it was conceived (fig.4).

Moore described travertine as having ‘a quality – ruddy, powerful, strong. You feel you haven’t got to handle it with kid gloves.’27 His language is a potent reminder of how important the physicality and directness of the relationship with the materials was for many, mostly male, twentieth-century sculptors. He occasionally remarked upon the need to be physically strong to carve stone – the implication seemingly being that it is an essentially masculine art – and explained in the early 1970s:

I like pushing at the soft material of clay, but I’m happier when I use a hammer and chisel. The hardness of stone, and the resistance it gives you, can give you a kind of force and a power because you are fighting the material. And the material gives back some strength, like a kettle with a lid on will give you a feeling of power, whereas an open pan just left with no lid and boiling gives you no sense of power. Well, the same thing happens with the carving of stone.28

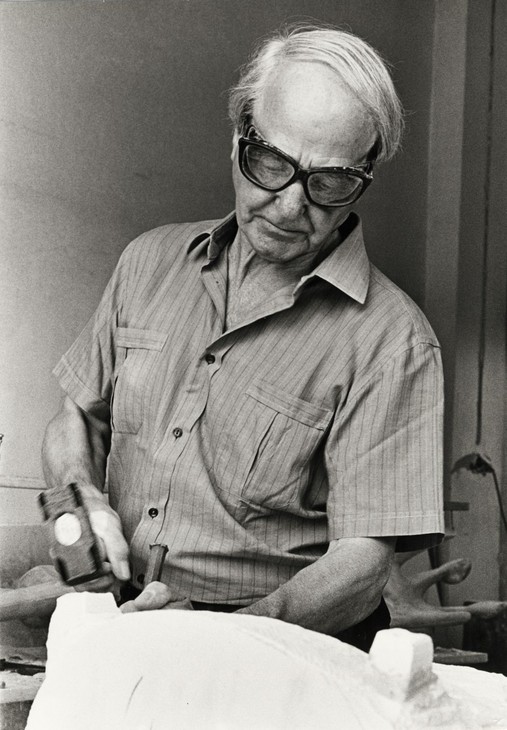

Until the outbreak of the Second World War Moore carved almost all his stone sculptures himself, the only known exception being the large Ancaster stone Reclining Figure 1930. He employed his first assistant, Bernard Meadows, from 1938, primarily to work on the wood carvings. Tellingly, even when, in later years, he no longer executed the carvings personally, in his photographic portraits Moore often encouraged an impression of his practice as inherently physical (fig.5).

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Composition 1931

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Composition 1931

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

During his career Moore used at least forty-one different types of stone, both sedimentary (such as Ancaster, Hornton and Roman travertine) and metamorphic (including Serpentine, African Wonderstone and at least ten different types of marble).29 This variety shows how he always remained eager to experiment with new techniques and materials, even if this meant exploring approaches that contradicted earlier stances, as his changing views on the principle of truth to materials suggest. It was not until after the Second World War, however, that, thanks to his growing financial success, he was able to use his stone of choice for all his works. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s he often had to settle for whatever stone was available, occasionally using marble and alabaster blocks which he acquired from stonemasons and salvage yards, in the form of offcuts, old church statuary or discarded architectural features. This meant that in those years Moore had to make the most of each piece of stone. At times, he would reuse offcuts from larger works to carve the smaller individual elements for one of his multi-part pieces: the Cumberland alabaster forms in Four Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934 are believed, for example, to be offcuts from the block from which he had made Composition 1931 (figs.6 and 7). When he could afford to buy the material of his choice Moore often visited quarries and suppliers in various English regions, mainly in the Midlands and the North. In Cumberland he bought blocks of the local alabaster, which had first been used for sculpture by John Skeaping (see Mother and Child 1930–1); in Derbyshire he acquired Hopton Wood stone, which Jacob Epstein had used for Oscar Wilde’s tomb in Paris (see Head 1937); and from Edge Hill in Warwickshire he purchased green and brown Hornton stone (see Reclining Woman 1930). These stones are predominantly fine-grained limestone which, unlike the more friable and flat-coloured sandstone that is more common in Yorkshire, allowed Moore to achieve a better finish by exploiting the greater surface tension. From the late 1920s Moore also began to acquire materials from London suppliers. These offered a wider selection of stones from places including Scotland, Ireland and South-Western England (for example, the Portland and Purbeck quarries), as well as more unusual materials such as the Styrian jade he used for Mother and Child 1928 and the African Wonderstone of Head and Shoulders 1933.

Photograph showing Moore's Recumbent Figure 1938 sited in the garden of Serge Chermayeff's house at Halland, Sussex

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Photograph showing Moore's Recumbent Figure 1938 sited in the garden of Serge Chermayeff's house at Halland, Sussex

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The cost of materials and the inadequate size of his workspace were not the only limitations to Moore’s ambition in his early career. Often the quality and condition of the stone itself, which were sometimes affected by the way in which it was quarried, required significant compromises. For example, writing to Kenneth Clark about the transport to New York of the Chermayeff Recumbent Figure in 1939, Moore advised that

because the stone the figure is carved in (Hornton stone) can only be quarried in limited thickness, the figure had to be made of 3 horizontal layers of stone, which are dowelled & cemented together. It’s perfectly sound to do that, because the stones are laid on their natural beds, as they should be in ordinary building – but it means that in moving it about, it should not be lifted except from the bottom, so that there’s no risk of any separating.30

In 1947 Moore also suggested, with reference to Three Standing Figures 1947–8, that the ‘misuse’ of some quarries during the war had made certain types of stone unprocurable.31

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1930

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1930

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1924–5

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1924–5

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

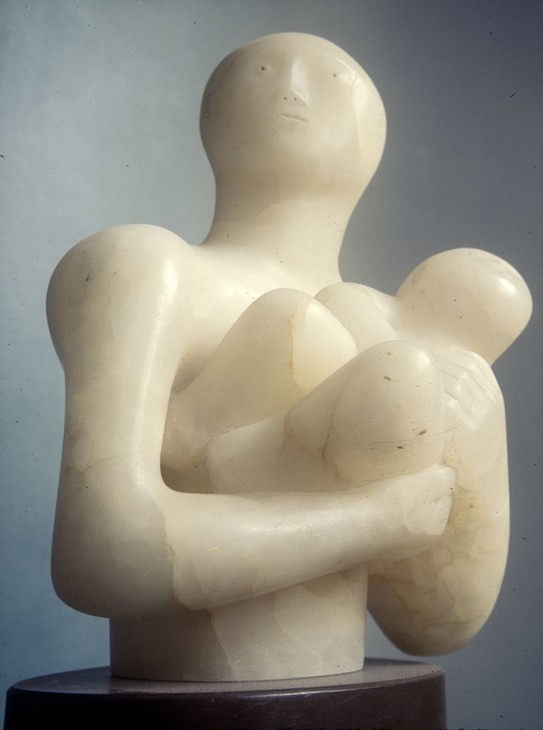

One of the reasons for Moore’s preference in his early career for rougher and vivid stones such as Hornton was the fact that, unlike white marble and alabaster, they do not look pristine even when freshly carved. Moore tended to use Hornton stone for heavier, more powerful forms, saving marble and alabaster for the more serene works: compare, for example, the alabaster Mother and Child 1930 with the Hornton stone Mother and Child 1924–25 (figs.9 and 10). His explanation of how he chose the material for the late carvings of the 1960s and 1970s is based on a similar principle: ‘In carving a sculpture, it is very important to match the right material with the particular subject in mind. In using white marble I give the forms a precision and refinement and a surface finish that I wouldn’t try to obtain with a rough textured stone such as travertine.’32

Moore carefully considered not only the visual but also the tactile qualities of a particular stone when matching it to a specific subject. For example, the smoothness and lightness of ironstone is highly suitable for very tactile small sculptures, hand-sized works such as Carving 1934 that could possibly be kept in the owner’s pocket, in the way Henri Gaudier-Brzeska had made fashionable in the 1910s. The exploration of the relationship of rough and smooth surfaces clearly appealed to Moore: in some works he chose to leave the chisel marks fully visible, even though the natural smoothness of the material would suggest a very different tactile experience – see, for example, the African Wonderstone Mother and Child 1934. At the opposite end of the tactile spectrum, travertine, which is often characterised by the dense concentration of naturally occurring small holes giving the surface a porous roughness, can be used on a monumental scale to suggest an affinity between the sculpture and vast expanses of rocky landscapes.

Climatic conditions also occasionally played a part in Moore’s choice of material for an outdoor work. The Hornton stone Recumbent Figure commissioned by Chermayeff was on loan to the New York World Fair when war broke out. The Museum of Modern Art took it over and exhibited it, throughout the war, in its sculpture garden. When it returned to England the sculpture was weather-worn, having been exposed to the extremes of heat and cold of New York and its sea air. ‘But at least I discovered’, Moore wrote, ‘that Hornton – a warm, friendly stone that I like using – is not suitable for exposure in intemperate climates.’33 Thus, when soon after the war the Museum of Modern Art asked Moore for a large work, he executed Three Standing Figures 1947–8 in Darley Dale stone because it ‘weathered well’ and would keep ‘clean in the sea air of New York’.34

Mid-career and late carvings

From the early 1940s until the end of the 1950s carving in both stone and wood played a less central role in Moore’s sculpture than it had before the war. However, in the early 1960s, when he started to spend extended periods near the Carrara quarries in Italy, Moore’s passion for stone was reignited and carving became important again in his practice.

The stone sculptures Moore made in the years from the outbreak of war to 1960 were almost all large commissions for public sites. They include Madonna and Child 1943–4 (Hornton stone, St Matthew’s Church, Northampton); Three Standing Figures 1947–8, Darley Dale stone, Battersea Park, London); Time/Life Screen 1952–3 (Portland stone, Time/Life Building, London); Harlow Family Group 1954–5 (Hadene stone, Harlow Water Gardens); and the Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–8 (Roman travertine, Unesco Headquarters, Paris). Although at this point Moore’s reasons for using stone remained mostly aesthetic and ideological, his attitude towards it, or at least towards certain types, was now also informed by the view that stone was the most suitable material for a monument (as different from a sculpture), above all, because of its hardness and durability. As he pointed out to curator David Mitchinson in 1981: ‘No doubt there is something about the resistance of hard stone which gives a finality that a soft material tends not to have. Also the length of time needed to carve into such a hard material gives something, a kind of permanence perhaps, that a soft material, done quickly, does not have.’35 It is also likely that having witnessed the widespread melting down of sculptures to procure metal to build military equipment during the war, Moore had come to consider stone a more appropriate material for long-lasting public commissions.

Moore continued to use stone for monumental public commissions through to the 1980s, as evidenced by works such as Stone Memorial 1961–9 (Roman travertine, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC), Square Form with Cut 1969 (black marble, Juan March Foundation, Palma de Mallorca) and The Arch 1979–80 (Roman travertine, Kensington Gardens, London), as well as Mother and Child: Hood 1983 (Roman travertine, St Paul’s Cathedral, London). However, although he once commented that when he resumed carving in stone in the 1960s he had in many ways picked up where he had left off before the war, there were several significant differences in his attitude towards materials and production methods – in addition of course, to the stylistic changes that appeared in all mediums.

Already in the early 1930s sculptors like Jacob Epstein, Frank Dobson and Moore himself had begun to reconsider their views on direct carving and after the war Moore started to question his dogmatic adherence to the principle of truth to material. In conversation with the critic David Sylvester in 1951 he declared:

When I began to make sculptures thirty years ago, it was very necessary to fight for the doctrine of truth to material (the need for direct carving, for respecting the particular character of each material, and so on). So at that time many of us tended to make a fetish of it. I still think it is important, but it should not be a criterion of the value of a work – otherwise a snowman made by a child would have to be praised at the expense of a Rodin or a Bernini. Rigid adherence to the doctrine results in domination of the sculptor by the material. The sculptor ought to be the master of his material. Only, not a cruel master.36

Now convinced that these principles were too restrictive, Moore contended that the ‘vision’ behind the work had to take precedence over the material. Thus, he came to accept that materials and methods which he had previously sidelined, such as bronze and modelling, allowed him to achieve, in compositional terms, forms that were impossible in stone: ‘You can make your figures long and thin, wider at the top than at the bottom, giving them uplift, a soaring feeling.’37 Moreover, casting in bronze allowed Moore to create sculptures in editions, an important consideration given the growing demand for his work.

Although this ideological shift did not affect Moore’s lifelong passion for working in stone, it did have far-reaching consequences on the way he used it. First, as a more experienced artist capable of controlling the material in more sophisticated ways, Moore now had the freedom to choose whether to work with or against the appearance of the stone. Secondly, unlike in the early part of his career, when he could almost only afford irregular blocks and offcuts and he tended to respond to their shape, he was now able to choose the most suitable blocks and was therefore freer to work following his inspiration, instead of letting the material suggest an idea. Moreover, Moore was now less afraid of taking risks with the stone (not least because the loss of a block would not be as damaging financially), which gave him greater freedom to experiment with form. But perhaps most importantly Moore was no longer dogmatic about the use of certain types of stone, and opened up to the possibility of using, for example, white marble, which he had earlier discarded because of its historical association with classicism (see Two Forms 1964 and Archer 1965). In fact, from 1961 Moore used for his stone sculpture almost exclusively marble, travertine and serpentine.38

Henraux

A determining factor in this change of attitude was Moore’s collaboration with stone merchants Henraux, the owners of the quarries of Monte Altissimo at Querceta, near Carrara in Tuscany, known worldwide as Michelangelo’s favourite source of marble. Moore visited Querceta in early 1957, when he was working on the Unesco Reclining Figure. Henraux had supplied the Roman travertine used for the new Unesco building in Paris, outside which the work would be sited, and Moore wanted to use the same stone for his sculpture. When it emerged that the cost of shipping the blocks to England would have been prohibitive, he decided to make the sculpture at Henraux instead. The experience was so positive that Moore regularly returned to Italy to make stone carvings for the rest of his career. From 1965 he owned a villa in nearby Forte dei Marmi, and for many years he spent at least two months every summer working in Tuscany.

Unlike his early interactions with stone merchants and quarries, on which very little is known, Moore’s work in Italy is quite well documented. Henraux’s biggest attraction was for him the superb quality of the materials it stocked: ‘One can find marble that is completely black and marble that is completely white and nearly every colour in-between. It’s simply terrific’, he wrote in 1973.39 Moreover, the merchants offered all the technical support Moore needed to create monumental stone carvings, and the convenience of working very near the source of materials, which also meant significant savings in transport costs. At Henraux he had access to a small studio in the stone yard and could use all of their facilities, from cranes to carving tools (including, from the early 1980s, pneumatic carving, which is much faster but as precise as hand carving). From the early 1960s Moore employed two local assistants, sculptor Sem Ghelardini and master carver Sergio Benedetti, whom he entrusted with the execution of the majority of his stone sculptures.

Henry Moore

Photograph showing the support of Standing Figure 1971–72

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Photograph showing the support of Standing Figure 1971–72

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The fact that sixty years after his first marble carving (Dog 1922) Moore was still working in stone is a compelling reminder of how important it was in his practice and vision. Stone was arguably his favourite material for sculpture, even during the periods when most of his output was in bronze. The only significant break in his use of stone occurred during the Second World War, essentially because of the uncertainty of the times and the difficulty of sourcing good blocks. It could even be argued that stone influenced his works in other materials, but not the reverse. From the practice of developing a sculptural idea starting from a found pebble to the recreation of the visual and tactile effects of stone in bronze works such as, for example, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960, stone was always at the forefront of Moore’s practice. And, in spite of his changing treatment of it at different stages his career, he never doubted its centrality in his art. This is because for Moore stone represented much more than a material to make works with. It was a perfect metaphor for the evocative relationship between sculpture and nature that had such a central role in his art.

Notes

See John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore: My Ideas, Inspiration and Life as an Artist, London and New York 1986, pp.22–5. Moore first visited St Oswald’s, the parish church of Methley, during a school trip organised by the Headmaster of Castleford Secondary School, T.R. Dawes. The sandstone building, dating from the fourteenth and fifteenth century, is decorated with medieval carved corbels depicting angels and grotesque figures. The church also houses a significant group of funerary monuments: Sir Robert Waterton (died 1424) and his wife Cecilia (alabaster recumbent figures); Lord Welles (died 1461) and wife (alabaster recumbent figures); Sir John Savile (died 1606), his son Sir Henry (died 1632) and his wife (tall tomb chest with black Ionic columns); Charles Savile (died 1741) and wife (by Peter Scheemakers); John Savile, 1st Earl of Mexborough (died 1778) (by Joseph Wilton).

Hedgecoe 1986, p.35: ‘In Yorkshire in Adel Woods just outside Leeds, there was a big rock ... that I’ve called Adel Rock. That influenced me quite a bit. For me, it was the first big, bleak lump of stone set in the landscape and surrounded by marvellous gnarled prehistoric trees. It had no feature of recognition, no element of copying of naturalism, just a bleak, powerful form, very impressive.’

Erich Steingraber, ‘Henry Moore Maquettes’, Pantheon, July–September 1978 (extended book version), p.55.

Hedgecoe 1986, p.95. This figure is not to be taken literally: on p.450 of the same book Moore suggests that between 1920 and 1940 ‘nine out of every ten sculptures I made were carvings’, presumably including here the wood carvings.

Percentages are calculated from the number of sculptures recorded in the catalogue raisonné, not the total number of objects (i.e. a bronze edition is treated as one work). It is worth stressing that whereas the large late carvings took months and teams of people to execute, Moore could complete one of the early ironstone pieces on his own in less than a week.

‘On Carving: Henry Moore in Conversation with Arnold Haskell’, New English Weekly, 5 May 1932, p.66.

The Raising of Lazarus and Christ Arriving at the House of Mary and Martha. See Chichester Cathedral’s booklet Chichester 900, Chichester 1975, p.11. Moore later acquired casts of these reliefs for his personal collection.

Henry Moore, letter to Jocelyn Horner, [August 1923], Leeds Museums and Galleries Archive of Sculptors’ Papers, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds.

See Judith Collins, ‘Plastic Forms and Truth to Materials’, Carving Mountains, exhibition catalogue, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge 1998, p.27.

Moore first visited Stonehenge as a student in 1921. In 1972–4 he made a number of drawings of the site and published the Stonehenge portfolio (fifteen lithographs and one etching).

‘Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites’, Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.270.

Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London, 1934, pp.29–30.

Four of these carvings were shown at the Leicester Galleries in April 1931: Reclining Figure 1930, Mother and Child 1930, Head 1930 and Head 1930.

Terry Friedman, ‘1921–1929’, Henry Moore: Early Carvings 1920–1940, exhibition catalogue, Leeds City Art Galleries, Leeds 1982, p.22.

Moore used stones from all three main petrological categories (for some of the lost and destroyed carvings the stone type was not recorded). They are listed here with the area of origin when known, and type or colour if relevant: Sedimentary: Alabaster: Cumberland and white, Ancaster (Lincolnshire), Bath (Somerset), Burgundy (France), Corsham (Wiltshire), Corsehill (Dumfries and Galloway), Darley Dale (Derbyshire), Hadene (Derbyshire), Ham Hill (Somerset), Hopton Wood (Derbyshire), Hornton (Oxfordshire): blue, brown and green, Ironstone (Norfolk), Mansfield (Nottinghamshire), Portland (Dorset), Purbeck (Dorset), Stalactite (former Czechoslovakia), Travertine: red and Roman (Lazio, Italy). Metamorphic: African Wonderstone, Anhydrate (Egypt?), Green Gneiss, Marble: Armenian, bird's eye, black, black Abyssinian (Ethiopia), Carrara (Tuscany, Italy), Rio Serra (Tuscany, Italy), Rosa Aurora (Portugal), Verde di Prato (Tuscany, Italy), white crystalline, Serpentine: black and green, Slate, Soapstone, Styrian Jade (misnomer for pseudophite). Igneous: Granite: black and white, Greenstone (Africa), Brick (which Moore used on one occasion, for the Wall Relief 1955, Bouwcentrum, Rotterdam) and concrete (which Moore often carved after casting and occasionally used in combination with stone) could also be added to the list, as well as the different types of found flints and pebbles incorporated into plaster or clay maquettes, for the detailed identification of which more research is required.

David Sylvester, Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1951, p.4.

‘Henry Moore Talks about My Work in a Special Interview with Tom Hopkinson’, Books and Art, November 1957, p.29.

In the early part of his career Moore predominantly made his stone carvings from sketches and drawings, only very rarely starting with a three-dimensional model. One of the very few known exceptions is a terracotta maquette closely related to the brown Hornton Carving 1936 (private collection; maquette, Henry Moore Foundation). Among the most significant groups of preparatory sketches for carvings is the Sketchbook 1928: West Wind Relief, which includes several studies (although none exactly prefiguring the final sculpture) for Moore’s first major commission, a Portland stone relief for the new Headquarters of London Transport at St James's Underground Building (West Wind 1928–9). After the war, when he mostly concentrated on bronze, maquettes became Moore’s favourite method of developing sculptural ideas in all materials.

Sebastiano Barassi is Senior Curator at the Henry Moore Foundation.

James Copper is Sculpture Conservator at the Henry Moore Foundation.

James Copper is Sculpture Conservator at the Henry Moore Foundation.

How to cite

Sebastiano Barassi and James Copper, ‘Henry Moore and Stone: Methods and Materials’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www