‘An essentially different kind of rhythm’: Rediscovering Henry Moore’s Sculpture in Wood

Ann Compton

Moore created some of his most important and innovative works in wood. Ann Compton presents the first detailed analysis of his technical and aesthetic achievements in this medium, situating his works in the contexts of contemporary sculptural practice, the market and the traditions of art education.

During the 1930s Henry Moore made important formal experiments while carving in wood and these, in turn, led him to create more open compositions in other materials. His earliest works in wood were upright single abstract figures carved in exotic timbers. In the early to mid-1930s, however, Moore worked with native species and from 1935 made crucial advances in his exploration of the reclining figure using elm (all his previous horizontal figure compositions had been in stone). After the Second World War, when many of Moore’s works were fabricated at Carrara in Italy or at foundries in Britain and Germany, he continued to carve large figures in elm at his studio in Perry Green.

Gemma Levine

Henry Moore's Reclining Figure: Holes 1976–8 at an intermediate stage and its plaster maquette, 12 April 1978

Tate Archive

© Gemma Levine/Tate

Fig.1

Gemma Levine

Henry Moore's Reclining Figure: Holes 1976–8 at an intermediate stage and its plaster maquette, 12 April 1978

Tate Archive

© Gemma Levine/Tate

Plate I of Henry Moore at the Serpentine 1978 showing Reclining Figure: Holes at an early stage of carving

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Plate I of Henry Moore at the Serpentine 1978 showing Reclining Figure: Holes at an early stage of carving

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Overall then, Henry Moore: Wood Sculpture is more tantalising than informative. Yet there has been no fresh attempt to document and analyse his work in this material over the last thirty years and there remain a number of significant unanswered questions surrounding this area of his practice. What were the particular challenges involved in working in wood and how did Moore overcome these? To what extent do his sculptures in wood differ aesthetically from his works in other materials? And how do these sculptures relate to a wider cultural context and to works in this material by other artists?

Moore’s sustained engagement with carving in wood began in 1930 and, over the next two years, eleven out of a total output of forty sculptures in stone and wood were made from wood.3 This development coincided more or less with a similar change in the practices of several of his close associates, most obviously Barbara Hepworth. She showed a particularly strong group of wood sculptures made around 1929 at Arthur Tooth’s Gallery during October and November 1930.4 Hepworth’s husband, John Skeaping, began carving in wood in 1930 and between c.1932 and 1934 created a remarkable larger-than-life-size Horse in mahogany and pynkado.5 Among the wider circle of Moore’s friends, Gertrude Hermes, who, like Moore, had been a student at the Brook Green School of Drawing in the early 1920s, carved and exhibited works in wood from about 1926. In this same period Leon Underwood, the founder of Brook Green, was working on Totem to the Artist 1925–30, and he made a number of other striking sculptures in wood during the early 1930s.

There are significant aesthetic continuities between work by these younger practitioners and the first-generation modernist sculptors, Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. However, wood as a sculptural material had played almost no role in the practices of any of these older artists. Indeed, Epstein worked exclusively in stone or bronze and Gaudier made one memorable work in wood – a totemic portrait of Ezra Pound.6 Only Gill produced some carvings in wood but the earliest of these dates from about 1922 and they remained a small part of his oeuvre. The art theoretical positions articulated by Gaudier-Brzeska and Gill also revolved around stone not wood. Gaudier-Brzeska’s influential statement in Blast proclaimed, ‘Sculptural energy is the mountain’, a compelling image that Moore, among others, took up in later years.7 Eric Gill repeatedly identified himself, and by extension, modernism with the honest practices of a stone carver and wrote extensively on the virtues of carving directly in stone.8

Although the adoption of wood as a sculptural material by Moore, Hepworth and Skeaping et al is one of the differences between the older and younger generation of modernists, it has prompted little direct comment in art historical texts. It appears there has been a tacit acceptance of David Sylvester’s view, outlined in his authoritative essay in the 1968 Arts Council Henry Moore catalogue, that Moore’s carvings in wood were sometimes ‘freer’ and ‘more open’ than other pieces but overall did not ‘possess an essentially different kind of rhythm’ from his sculptures in stone.9 There also seems to be an assumption that the advent of carving in wood was embedded in these artists’ innovative assimilation of non-European sculpture.

Henry Moore

Standing Figure 1923

Manchester Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Standing Figure 1923

Manchester Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

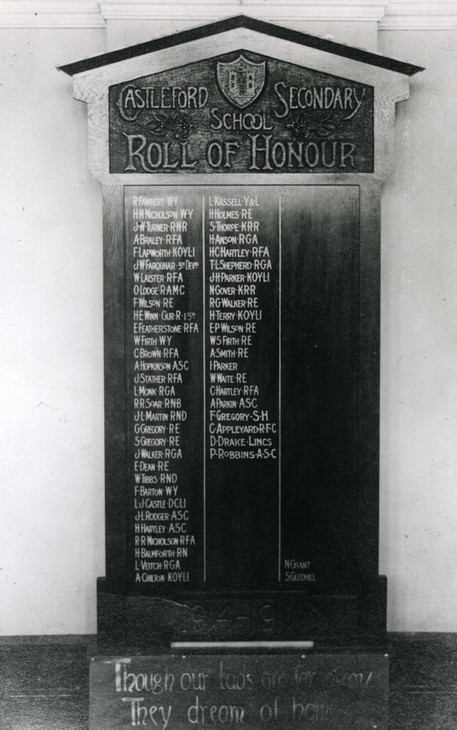

An important contextual point is that the perception and status of carving in wood was undergoing significant changes in Britain over the period in which Moore and his friends were developing an interest in art, studying at art school and embarking on their professional careers. In the nineteenth century wood was considered a utilitarian material, only suited to making architectural embellishments and small-scale functional or decorative objects and therefore inappropriate for the highest forms of the sculptor’s art.12 But over the course of the early decades of the twentieth century artists’ attitudes gradually changed and wood once again became an accepted fine art material. In the same period a national network of courses teaching wood carving was established as part of a wider revival of handicrafts that originated in the mid-Victorian period and was greatly stimulated by the Arts and Crafts movement at the end of the nineteenth century.13 The growing popularity of wood carving in fine art and craft practice thus followed parallel, and occasionally intersecting, paths, especially in regard to the dissemination of technical skills. The few surviving examples of Moore’s very early carvings mirror this wider pattern.

Henry Moore

Roll of Honour c.1916

Castleford High School, on loan to Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Roll of Honour c.1916

Castleford High School, on loan to Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The skill-base Moore developed in the early years at Castleford was probably consolidated at Leeds School of Art between 1919 and 1921. Here he had the opportunity (also shared by Barbara Hepworth) to work under the experienced wood carver John Lawrance (1862–1958), who had taught at the school since 1911 and who had knowledge of other specialist craft techniques, such as carving cameos and semi-precious stones.16 Recognising Moore’s early acquisition of wood carving skills is important because it gave him a significant advantage later in his career (workshop lore states that it is best to learn this technique before working with stone rather than vice versa). The reason wood is such a challenging material is that all species have a distinctive grain that lends itself to a specific type of work and finish. Wood changes constantly throughout seasoning, carving and its subsequent life depending on the heat and humidity an object is subjected to as well as how the wood is worked. A further key difference is that cutting wood involves working with both hands: one holds the handle and pushes forwards while the other rests on the blade to exert resistance. This duality allows the chisel or gouge to move steadily through the wood. By contrast, working in stone involves far less reference to grain, considerably fewer specialist tools and each stroke of the hammer on the chisel removes a chip off the block.17 Experienced stone carvers say they can listen to the block of stone and feel when it will split through the strain on the chisel, but wood carvers describe a still more active dialogue with their material. They have to learn the character of each type of wood and take account of its ‘likes’ and ‘dislikes’ in the way that it is worked.

Henry Moore

Head of a Girl 1922

Manchester Art Galleries

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Head of a Girl 1922

Manchester Art Galleries

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s treatment of Head of a Girl proved transitional. He gave the next piece, Standing Woman 1923, a uniformly smooth finish and adopted this approach in all his future works. This development could also be attributed to the influence of Brancusi (see, for example, his polished Torso of a Young Man 1917–22) or to Moore’s study of non-European sculpture. But it is also in line with a wider tendency among British artists working in wood at this time, which seems to be associated with their effort to differentiate the use of wood in fine art from its utilitarian past. Up to the early 1900s carvers working on decorative or architectural pieces in oak or other hardwoods prized an unpolished surface as well as the visible traces of the maker’s tools in the work. These practitioners argued that this technique displayed wood’s natural qualities to their best effect but artists creating sculpture in this material during the early twentieth century took the opposite view. They felt that the grain and sensory quality of the wood were enhanced by disguising the use of the chisel or gouge and by smoothing the surface to a light sheen or even to a high polish. This new direction is exemplified in the practices of several slightly older sculptors who were established sculptors in wood and had links to the circle in which Moore, Hepworth and Skeaping and others were moving in the 1920s.

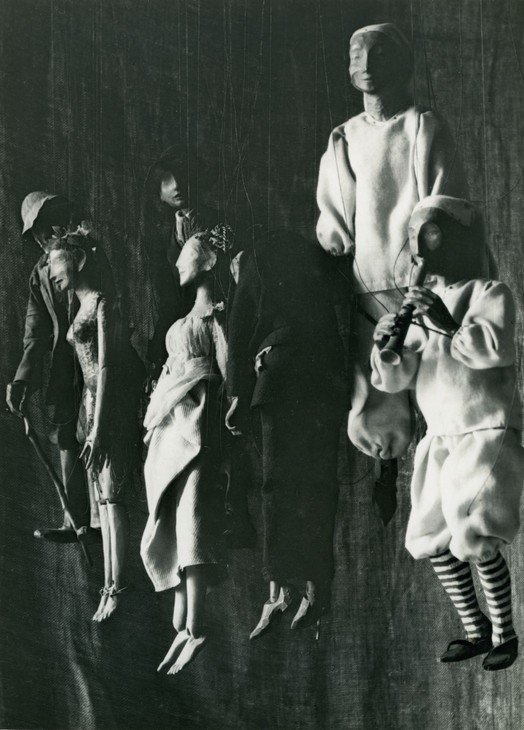

William George Simmonds

Seven Marionettes Hanging Up Photographer unknown

Photograph TGA 9329

Tate Archive

Fig.6

William George Simmonds

Seven Marionettes Hanging Up Photographer unknown

Photograph TGA 9329

Tate Archive

One such artist, William George Simmonds (1876–1968), was a close friend of the principal of the Royal College of Art, William Rothenstein (fig.6).21 Simmonds was a sculptor and puppeteer who lived in the village in Gloucestershire where Rothenstein had his country residence.22 Rothenstein commissioned Simmonds to carve a lay figure for the Royal College of Art in 1921 and invited him to teach wood carving in 1924.23 It is uncertain when Simmonds took up this offer but his sculptures, which were chiefly of animal subjects with softly buffed, highly tactile surfaces, were well known in the 1920s and Moore would have seen several examples when visiting Rothenstein’s house in London or at the Tate Gallery, which purchased The Farm Team c.1924–8 in 1929. Moore may also have attended one of Simmonds’ performances with his hand-carved marionettes, which were widely admired in the 1920s and 1930s for their innovative fusion of European and non-European puppet traditions. Another sculptor in wood was Alfred James Oakley (1878–1959), who followed his father’s career as a chair maker in High Wycombe before studying art.24 Alfred settled at 5 Mall Studios in Hampstead in 1922. Five years later, Hepworth and Skeaping moved in next door and Moore was a near neighbour after his marriage to Irina Radetsky in 1929.25 Oakley began exhibiting works in wood at the Royal Academy in 1925 and the following year the Tate Gallery acquired Mamua (fig.7). This was one of a number of Oakley’s wood carvings dating from the second half of 1920s, in which he used the theme of a woman’s head to embody cultural difference. Although some of these sculptures have a decorative quality and lack Moore’s or Hepworth’s nuanced assimilation of African and Oceanic aesthetics, the older artist’s engagement with non-European cultures is nevertheless clear.

In 1931 the work of Simmonds and Oakley was included in Kineton Parkes’s two-volume international account of The Art of Carved Sculpture.26 One of the most interesting aspects of this survey of sculptural practice is its inclusiveness. Parkes covers a wide range of artists from those, such as Simmonds and Oakley, who had links to handicraft or were associated with traditional fine art practices right through to modernist sculptors like Moore, Hepworth, Skeaping, Hermes and Underwood. Across this broad spectrum, Parkes discusses the work of some twenty to thirty artists who were carving in wood, of which the great majority were associated with the Royal Academy. He clearly regarded working in wood as a mainstream activity that had become an increasingly evident feature in exhibitionary cultures during the latter part of the 1920s, rather than the preserve of the avant-garde.27 An important question implied by Parkes, though not actually addressed in his account, is why were so many artists turning to wood as a sculptural material at this time?

A direct and pragmatic response to this issue was proposed by the sculptor Alan Durst (1883–1970) in a paper that he read to members of the Art Workers Guild in February 1931 during an evening of lectures and debate on ‘Wood as a Sculptor’s Medium’.28 The main thrust of his text was that sculptors needed to find new markets having lost architecture as their major source of employment because building styles had become more streamlined and included less carving (a point no doubt intended to prod the consciences of members of that profession who formed the backbone of Guild membership). Durst recommended making an active response to this problem and targeting homeowners who, he said, represented an increasingly important category of patrons. He argued that the familiarity of wood as a material in everyday use, its hardwearing yet tactile qualities, combined with pleasing effects of grain and colour made it the perfect material for middle class collectors wishing to add beauty to their homes. Durst’s analysis was astute; it picked up on a recent trend in the art market and explicitly connected sculpture in wood with these developments. From about 1925 a number of London galleries had made shows that combined fine art and hand crafted objects for the home.29 Some of these exhibitions concentrated on functional works, like those organised by Prudence Maufe at Heal’s Mansard Gallery, while other shows gave greater prominence to fine art exhibits and a subsidiary role to furnishings, such as Pictures Sculptures and Pottery by some British Artists of Today organised by the painter J.D. Fergusson at the Lefevre Gallery in 1925.30

Changes in teaching practices that encouraged students to bridge fine art and design took place at about the same time. William Rothenstein restructured departments at the Royal College of Art and brought in the artist Paul Nash to teach design (1924–5) and William Staite Murray as head of pottery (1925–39). He also swept away the traditional modeling curriculum by ‘throw[ing] the door open between the pottery & woodcarving workshops’.31 Moore’s appointment as an assistant tutor in the sculpture department occurred at this moment, as did Rothenstein’s attempt to get William Simmonds to join the College staff in 1924 and his appointment of Alan Durst to teach wood carving in 1925.32 A number of Moore’s student peer group embraced this invitation to cross the boundary between fine art and handicraft. Among them were Enid Marx, who used wood block printing to create innovative printed textiles, and Moore’s close friend Cecilia Dunbar Kilburn, who later founded the art and design gallery Dunbar Hay Ltd. with another Royal College of Art colleague, Athol Hay.33 Outside the college, Gertrude Hermes was creating some remarkable door furnishings in the mid-1920s while also making sculpture and establishing herself as a maker of innovative woodcuts and illustrations.

Moore’s response to this trend towards the fusion of art and craft was less direct and more complex. In 1928 he had a negative experience carving the West Wind for the London Underground Headquarters at 55 Broadway, which he afterwards said ‘symbolised for me the humiliating subservience of the sculptor to the architect’.34 This led him to focus exclusively on gallery sales rather than undertaking further architectural commissions (a surprisingly bold decision for such a young artist because it eliminated potentially lucrative work from his practice). Between c.1928 and c.1930 he experimented with applying sculpture to chair backs, designs for a garden bench,35 and to wall lights in terracotta. Moore’s move into sculpting more consistently in wood in 1930 therefore commenced at about the same moment that the last of these functional objects were made. While we cannot be sure that these changes were driven by commercial considerations, he was certainly alert to the ‘warmer, more human feel’ of wood and so may have anticipated working in this material would make his sculptures more appealing to middle-class homeowners.36

Moore’s choice of exotic wood for many of his early carvings certainly fitted with a long-term trend in home furnishing. The use of luxury materials in the domestic environment had increased in the nineteenth century when imported timbers from the Empire were being actively promoted. This remained popular during the 1920s and 1930s when Art Deco designs and ‘moderne’ furniture influenced by Parisian styles were in fashion. Permanent displays at London’s Imperial Institute in South Kensington and international exhibitions (including the British Empire Exhibition of 1924 for which Moore and fellow Royal College of Art students created some heads to decorate the cotton stand) were one of the means of increasing sales within the timber and furniture trade.37 In 1926 Lieutenant-General William Furse was appointed director of the Imperial Institute and began a programme of dispersing duplicate or surplus exhibits to the Victoria and Albert Museum and other London institutions. Moore states in Henry Moore: Wood Sculpture that some of his early works were carved from sample pieces of exotic wood he received from the Imperial Institute making a serendipitous connection between the promotion of empire trade, fashions in home furnishings and his sculpture.38

It was through his choice of group exhibitions that Moore targeted the domestic market most overtly. Early examples of this were two successful shows at Zwemmer’s Gallery, Room and Book in 1932 and Artists of To-Day in 1933. The exhibits in both shows comprised an ambitious selection of fabrics, furniture, glass, lamps, rugs, papers, paintings and sculpture creating ‘the novelty’ of seeing ‘wares assembled in the relationship of the ordinary domestic interior’.39 The first of these exhibitions, Room and Book, was organised by Paul Nash, Moore’s friend and former colleague at the Royal College of Art, who also published a book on art and design with the same title.40 Here Moore’s sycamore carving of a Mother and Child was placed in front of hand-blocked fabric designed by Enid Marx and similar conjunctions took place in the Artists of To-Day exhibition the following year. This led the Observer critic to remark that such displays ‘demonstrate that adequately evolved surroundings are desirable, if not indispensible, so as to get the full ornamental value out of a picture or piece of sculpture of the type usually referred to as being of “advanced tendency”.’41 In other words, the combination of art and design created a viewing environment that the public found more sympathetic for understanding and appreciating modern art. Later shows, such as Unit One, Circle and the Abstract and Concrete exhibition, combined works by artists, designers and architects, capitalising on this pragmatic strategy for reducing potentially hostile criticism.

Meanwhile the solo shows Moore had with his main dealer, the Leicester Galleries, made subtle suggestions to buyers about the works’ suitability for the home while giving full scope for his wider ambitions to come through. The exhibition space in the south-east corner of Leicester Square was divided into three domestically-sized rooms which were rather plainly decorated.42 This resembled advanced approaches to interior decoration while serving the practical purpose of making repainting between shows easy. Potential associations between works shown in these spaces and the viewer’s home were also intimated by William Staite Murray’s and Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie’s pots that were part of the Leicester Galleries’ stock items in the 1930s.43 Moore exhibited only two carvings in wood at his first exhibition with the Leicester in 1931 but included seven works in this material in his second show of 1933. The success of the Room and Book exhibition in 1932 and the accumulating proof that works in wood found buyers might account for this increased presence. Some of Moore’s sculptures in wood were acquired by fellow artists like Jacob Epstein, others by early patrons, such as the Chairman of Lund Humphries, E.C. (Peter) Gregory, and a third important contingent were women (for example, Fanny Wadsworth and Margaret Nash). As key decision-makers in regard to homemaking, women constituted an increasingly important sector of the buying public.44

Henry Moore

Torso 1927

Wood

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Torso 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

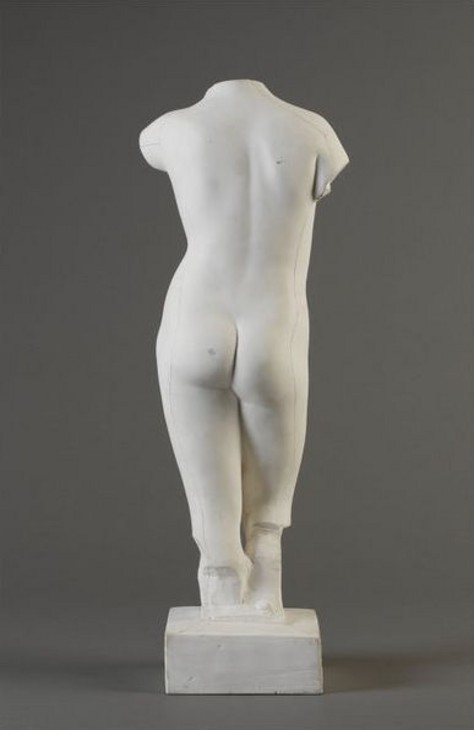

Alphonse Legros

Torso of a Woman 1890

Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig.9

Alphonse Legros

Torso of a Woman 1890

Victoria and Albert Museum

Moore’s handling of form and subject in his sculptures in wood show the same careful modulation applied to the context in which the works were exhibited. He avoided domesticated themes like children and animals, instead selecting ambitious fine art subjects but on a scale suited to the home. Between 1930 and 1934 his carvings focused on single, usually upright, female forms. These works continue an idea he explored in Torso 1927 (fig.8) in African Wood (the only sculpture in wood Moore produced between the mid and late 1920s). This three-quarter length headless and armless female form with gentle undulations that hint at breasts and buttocks belongs to a compositional type that had been interpreted by many artists over the preceding decades. Alphonse Legros’s plaster Torso of a Woman 1890 (fig.9) was an important early example belonging to the Victoria and Albert Museum that Moore would have known from his early days at the Royal College.45 British artists, ranging from Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Frank Dobson to scholars at the British School at Rome, such as James Woodford and David Evans, had since reworked the idea, revealing how easily it lent itself to varying degrees of abstraction, while simultaneously invoking allusions to antiquity (a number of similar classical fragments had been excavated by archaeologists).46 Moore found new ways to reinterpret the truncated torso. Carved from boxwood, Figure 1930 has simple knobs and corners that suggest face and limbs without actually delineating them and an arched, cave-like space between the legs. The small boxwood pieces of 1932, Girl and Figure, vary the form by introducing arms and legs (fully separated from the main trunk in the latter work), but any hint of realism is countered by the doll-like scale, diminutive torso, mask-like faces and rigid pose which are more suggestive of a ritual object than a living being. Other pieces of roughly the same date, Figure 1932 (beech wood) and Composition 1933 (lignum vitae), take the composition in a still more playful direction, with the figure occupying uncertain ground between boot, peg, cocoon and phallus.

Photograph of Figure 1931 taken in c.1931–4, reproduced in Herbert Read, Henry Moore: Sculptor, An Appreciation, London 1934, pl.21

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Photograph of Figure 1931 taken in c.1931–4, reproduced in Herbert Read, Henry Moore: Sculptor, An Appreciation, London 1934, pl.21

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

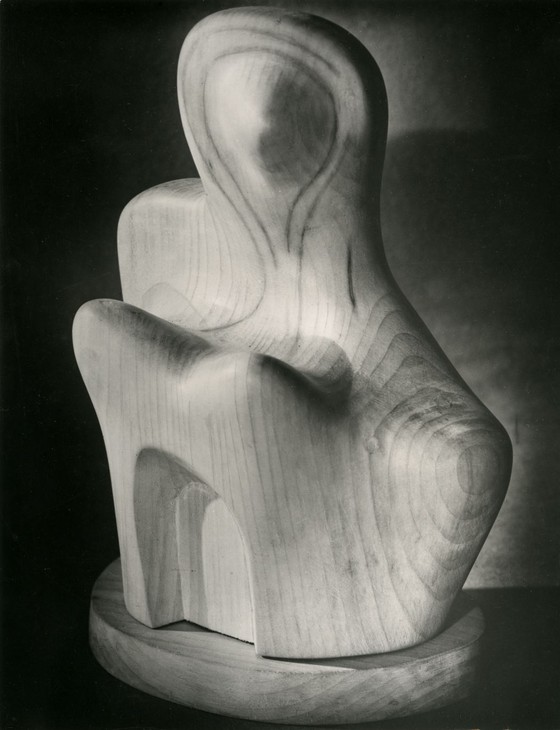

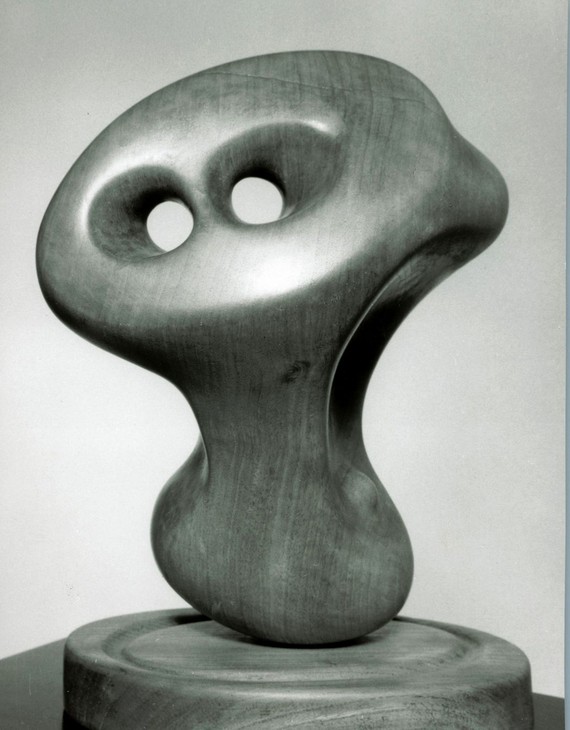

Henry Moore

Composition 1933

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Composition 1933

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Family 1935

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Family 1935

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

As the 1930s advanced it was in wood that Moore made important aesthetic experiments. Indeed, one of the major breakthroughs in his practice came in a 1933 carving in walnut titled Composition in which Moore first created holes as a sculptural form in their own right (fig.11). This differed from earlier pieces, which had been pierced to articulate a body’s outline, separating the limbs from the trunk in Figure (boxwood) and Composition (dark African wood), both from 1932. By contrast, the hole in Composition 1933 served a purely sculptural purpose that ‘made the spaces between forms as important as the forms themselves’.49 Coincident with this development Moore’s sculptures hovered more equivocally between representation and abstraction. Composition 1933 could be read as a head with eyes, a headless body with holes for breasts or even a fantastical creature. The year after this, another important departure occurred in Two Forms 1934, made from pynkado wood. Here the spatial opening up of the figure was taken a step further, so that the gaps between forms suggest the physical and emotional relationship of mother (or parent) and child as much as the solid parts of the sculpture. The sense of protectiveness, even anticipation, between the forms is increased by the larger element having a curved edge to the base which gives the viewer the sense that it might lean closer towards the smaller piece. These works have a particular elegance and purity but this was quickly superseded by a group of sculptures with a more rugged, bulky, rooted, functional air. Family 1935 (fig.12) sits squarely on its base. The figures are fully conjoined at the hip (or perhaps the leg or breast – any of these are possible), and the suggestion of a parent and child is made by the sculpture’s upper division into two blocky shapes. From some angles these resemble strangely sturdy ears (almost as if they belonged to an overgrown rabbit) while from others they take on the appearance of the levers or pedals of some primitive mechanical device. This same ambiguity occurs in works from the same year, like Carving (walnut wood) and Carving (African wood), which hover uncertainly between figuration and objects that belong to a pre-industrial past.

These developments occurred at a moment when Moore was not only consolidating his connections to the European avant-garde50 but also nurturing an alternative life away from the city. In 1931 Moore and Irina purchased a cottage at Barfreston in east Kent, which became their main base when he was not teaching in London.51 Most of Moore’s work from this date was created in these new, rural surroundings. Trees formed an important part of this existence and brought Moore into intimate contact with the growing habits and harvesting of native species and the role of woodlands in English culture and country life. A charming example of this could be seen in the churchyard over the garden fence at the cottage in Barfreston. Here the church bell was hung on a yew because the tower of the remarkable but diminutive Romanesque Church of St. Nicholas could not house one.52 Although Moore and Irina spent much of their time at home (she gardening and he relishing the opportunity to sculpt in the open air), they had a motorbike and later a car, and so could make excursions. Touring local landmarks was facilitated by guidebooks like Arthur Mee’s King’s England series, known for conversational, well-researched information aimed at sightseers made mobile by the expansion of car ownership. In view of Moore’s longstanding interest in early English sculpture, Canterbury Cathedral and St Bartholomew’s Chapel, Rochester would certainly have been on the itinerary. Moore and Irina may also have visited some of the ancient and remarkable trees that Mee inventoried alongside architectural and sculptural sites of interest. The guide’s presentation of England’s culture as being defined by the landscape as well as art and architecture reflected the emergence of a powerful lobby pressing for the documentation and preservation of all aspects of the nation’s heritage during the interwar period.

Campaigns aimed at popular audiences instilled a new level of awareness that numerous skilled trades were among the endangered aspects of rural life. Formerly these had been considered too commonplace to merit special attention but now there was interest in preserving them for posterity. The new medium of documentary film was one of the methods of capturing these working practices and short films were screened as part of longer programmes in cinemas nationwide. Kentish crafts that were at risk included trug and barrel making,53 but some of the most evocative footage concerned carving the legs of Windsor chairs or bodging. This was specific to High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire and Alfred Oakley, Moore’s (and Hepworth’s) near neighbour in Hampstead, would have known this trade, or even practiced it, in his youth.54 The bodgers worked in temporary encampments for a year or so at a time, which were set up in beech woods selected for the straight habit of the trees. After felling, the trunks were cut into sections the length of a chair leg and shaped with a hatchet and drawknife when the wood was still green. Next the pieces were turned on a pole-lathe, made from slender green branches lashed together and operated by a treadle and string, then passed to a workshop for final assembly into chairs. Documentaries such as these not only elevated the status of humble tradesmen to the dignity of craft practitioners but also highlighted the continuum between arboriculture, coppicing, handicraft and material cultures.

As a commuter, whose money was made in the city, Moore, like the cinema audiences who watched these films, had a consumer’s relationship with the countryside. However, as the 1930s advanced and his use of native woods for sculpture increased, his relationship to crafts associated with the fabrication of functional objects transcended that of spectator or campaigner. Some of the English timbers he selected fell within the ornamental carver’s established repertoire of materials, such as sycamore (Mother and Child 1931) and walnut (Composition 1933 and Carving 1935). Others, like boxwood (Girl and Figure, both 1932) occupy a middle ground between art and practical tasks since this wood is used for decorative purposes and for tasks like making sculptors’ tools for modelling clay and wood engravers’ blocks. But it was Moore’s introduction of elm that marks a definite switch to a material with pronounced functional associations.55 It is a hard wood, comparable to some extent to oak but unlike the latter was rarely used for decorative wood carving or sculpture because the grain of elm is very broad and twisted. This makes it difficult to carve and unsuitable for anything requiring a fine or detailed finish. The kinds of use to which elm was typically put were rugged tasks like making planks for wheelbarrows, the carts used for moving coal underground, coffin boards and outbuildings (oak was preferred for more ambitious and enduring structures). As it is very resistant to wet if kept permanently damp, docks were made from elm pilings and hollowed out elm trunks functioned as water pipes in the days before the use of steel or lead. Other applications arose from elm’s extraordinary resilience in situations where there were multiple strains from many directions such as the heads of mallets and the nave (or hub) of a cartwheel. How these last items are made illustrates the point. A piece of well-seasoned elm is turned on a lathe and then twelve or fourteen mortices are carved at a slight angle to hold the spokes of the wheel which are cut from ash or oak. Despite being deeply cut and carrying considerable tension (the metal outer rim of the cartwheel is heated so that it expands and then shrinks as it cools to fit tightly around the inner wooden portion), the elm wood nave remains a strong and durable part of the construction.56 This remarkable capacity clearly caught Moore’s attention because having experimented with some comparatively straightforward carvings in elm, like Hole and Lump 1934, he applied the principle to his first reclining figure in 1935. The twist in the composition – the head and shoulders face the shorter axis while the hips and legs are angled forwards lengthwise – coupled with deep openings in the chest and between the knees are all made possible because of elm’s unique toughness resulting from its twisted grain, even when cut from several angles.

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1935–6

Elm

Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1935–6

Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

So successful was the first reclining figure that over the next four years Moore carved two further works, each one larger than the last. This evolution arose from a growing confidence with managing the challenges of the process and his ambition to work on a larger scale. Looking back on this period Moore described the move into elm as a liberation that made carving some of his earlier pieces seem like ‘a mouse nibbling at a hole’.59 No less significantly the large elm sculptures brought his work in wood and stone into alignment compositionally; for the first time he was working on reclining figures in both materials. Indeed, there was a direct dialogue between works in wood and stone; the second and third figures in elm were carved before and after Moore’s first large opened out stone sculpture, Recumbent Figure 1938 (Green Hornton stone, Tate). In retrospect, this period marks the moment in his practice when ideas and forms became more important than the specific materials in which they were realised. The stringed figures Moore created in wood and string as well as lead and wire between 1937 and 1939 illustrate this tendency. These works all explore the relationship between form, space and an intermediary state embodied by the string or wire, which also serves to place the separate forms in a visible state of tension (an idea that may have grown out of the experience of carving the elm reclining figures).

The monumentality of the large elm reclining figures helped set Moore’s sculpture apart from any of his contemporaries, even from Barbara Hepworth who was also exploring the potential of working with open forms to extraordinary effect. Several other friends had worked in elm – see, for example, Leon Underwood’s Regenesis 1931–1 and Gertrude Hermes’s Three in One 1933 – but none of these works approached the complexity and scale of Moore’s sculptures.60 One piece that was closer in ambition to the reclining figures, although it resembled a seated Egyptian sculpture and had none of the openness Moore achieved, was Ossip Zadkine’s sculpture for Edward and Fanny Wadsworth’s garden at Maresfield in Sussex, which was commissioned in 1927.61 Moore referred to this work in Henry Moore: Wood Sculpture and may have met Zadkine at Maresfield because he and Irina were regular houseguests of the Wadsworths.62 The Statue for Garden63 was worked green and Zadkine’s experiences overcoming the technical challenges of making such a large wood sculpture and of managing the tree trunk as it was carved and gradually dried would certainly have been instructive. Although to some extent the lessons learned were about what to avoid since Zadkine’s garden figure broke into pieces after ten years, destroyed, Moore wrote, by ‘the woodpeckers and contrast of our English weather’.64 Recognition for the reclining figures in elm by Moore was manifested in important sales that helped build his growing national and international reputation. The Albright-Knox Art Gallery bought the first elm figure of 1935;65 in 1942 Wakefield Art Gallery acquired the second one dating from 1936; 66 and the reclining figure of 1939 was sold to Elizabeth Onslow-Ford. After the war the Albright-Knox Art Gallery purchased Upright Internal/External Forms 1953–4, and Upright Figure 1956–60 entered the collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. The third reclining figure changed hands a number of times in the 1960s and 1970s and set a record at auction for a work by a living artist when it was sold for $1,265,000 at Sotheby’s, New York, in 1982.67

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Once when I was in Moore’s studio and saw one of his reclining figures with the shaft of a belemnite exposed in the thigh, my vision of this unity was overwhelming. I felt that the squid in which life had created that shape, even while it swam in distant seas was involved in this encounter with the sculptor; that it lay hardening in the mud until the time when consciousness was ready to find it out and imagination to incorporate it in new form. So a poet will sometimes take fragments and echoes from other earlier poets to sink them in his own poems where they will enrich the new work as these fossil outlines of former lives enrich the sculptor’s work.71

Although the need for emotional appeals to an identification with the British landscape subsided as the 1950s and 1960s advanced, the link between Moore’s work and nature remained a recurrent trope in critical texts. The dominance of stone as the quintessential material of Moore’s carved sculptures overshadowed the more specific narratives surrounding his preference for elm as a material. In addition, critics had little substance to work with in relation to the significance of his choice of wood since the artist’s comments were limited to noting that before the days of Dutch elm disease elm was the cheapest wood that a sculptor could obtain in large pieces. Closer examination of this passing reference, however, reveals an important contextual relationship between Dutch elm disease’s devastating impact on the English landscape and the making of the reclining figures.

The first named outbreak of the disease occurred in the 1920s and 1930s. It was noticed in France in 1918 and its pathology (a fungus spread by a bark beetle) was established and named by a study in the Netherlands. In 1927 Dutch elm disease appeared in England and reached its peak in 1936. Moore certainly would have been aware of this because the progress of the epidemic was the subject of numerous news stories and the problem was no doubt discussed in the staffroom at Chelsea where Moore taught from 1931 to 1932. (Chelsea School of Art was part of Chelsea Polytechnic, and the Botany Department had a section devoted to the study of plant diseases.) Elm trees have a special place in the history of the countryside. As a genus they have given up sex, and the trees spread by putting out suckers. In normal circumstances this means that if elms are cut down (or blown up as they were in Flanders in the First World War) they re-grow from shoots below ground. By this means a stand of elms may live for many hundreds of years and as they were frequently cultivated for their shade and attractive foliage near dwellings, so their massive, dark, leafy habit became a familiar, verdant icon of rural life. But the elm’s dependency on cloning for renewal also makes them vulnerable to sickness. Dutch elm disease caused terrible losses in the 1920s and 1930s, but the second better known outbreak occurred in the 1960s when hundreds of thousands of trees were lost, practically eliminating elms from the English countryside. On both occasions some healthy trees were felled as a precaution in the hope that their removal might limit the spread of the disease. It is this latter group that helped make large pieces of elm available for carving because only wood free of the fungus or infestation can be used for timber or sculptural purposes.

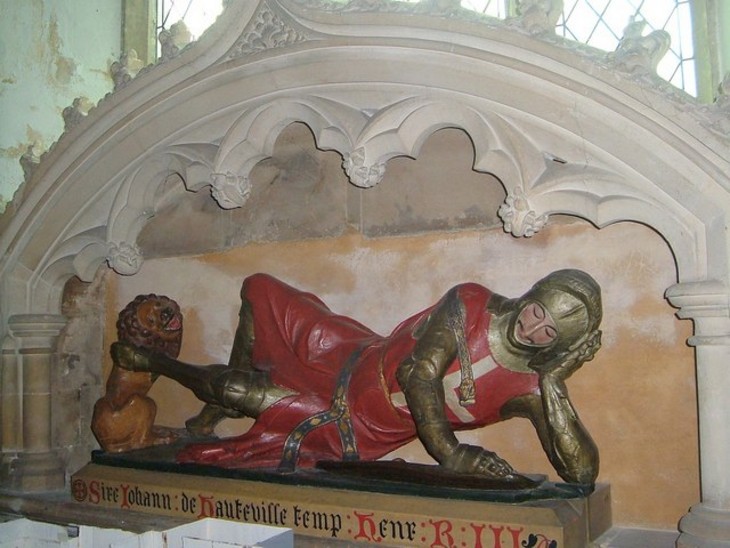

The tomb of Sir Johan de Hauteville, now thought to be Sir John Wych,1340-50

Church of St. Andrew, Chew Magna

Photo: Derek Harper

Fig.15

The tomb of Sir Johan de Hauteville, now thought to be Sir John Wych,1340-50

Church of St. Andrew, Chew Magna

Photo: Derek Harper

Notes

Henry Moore and Gemma Levine, Henry Moore: Wood Sculpture, London 1983. A selection of the photographs of Reclining Figure: Holes had been published earlier in Gemma Levine, With Henry Moore: The Artist at Work, London 1978.

These figures are derived from Herbert Read, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944, with corrections based on Moore and Levine 1983. There are two main changes to the 1944 figures for sculptures in wood between 1930 and 1933. Relief 1932 (wood and gesso; destroyed) was grouped with works in terracotta and concrete in 1944 (no.65) and with wood in 1983 (no.15). The latter placement has been adopted since it appears the forms were created from wood and that gesso was applied as surface colouring or decoration. Composition 1933 (walnut) was dated 1932 in 1944, but the later, now accepted, date has been used here (see no.77 in 1944 and no.18 in 1983). There are two other important date changes to the 1944 catalogue that should be noted: Head of a Girl 1922 (Manchester Art Galleries; no.3 in 1983) was dated 1923 in 1944 (no.71); and the first Reclining Figure in elm of 1935 (no.27 in 1983) was dated 1936 in 1944 (no.83).

New Sculpture by Barbara Hepworth and John Skeaping, exhibition catalogue, Arthur Tooth and Sons, London 1930.

Skeaping’s Horse 1934 (Tate N06129) was presented by the Zoological Society of London to the Tate Gallery in 1945.

‘Vortex. Gaudier Brzeska.’, Blast, June 1914, p.155 (facsimile reproduced in Evelyn Silber, Gaudier-Brzeska: Life and Art, London 1996). Henry Moore’s words, adapted from Gaudier-Brzeska, have been widely quoted. They originate in an untitled text for the Architectural Association Journal, May 1930, pp.408–13.

Henry Moore Early Carvings 1920–40: A Catalogue with Three Essays by Ann Garrould, Terry Friedman and David Mitchinson, exhibition catalogue, Leeds City Art Galleries, Leeds 1982, p.23 and pp.54–5. Moore’s Standing Woman was no.17 and the British Museum god figure known as A’a was no.6. For an image of this work see http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=502783&partId=1&museumno=Oc,LMS.19&page=1 , accessed 11 October 2013.

See, for example, the discussion of Akua-Ba, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/skeaping-akua-ba-t07862 , accessed 11 September 2013.

The School of Art Wood Carving in South Kensington was the principal teachers’ training college. There were also correspondence courses and numerous local teachers (many trained at the School of Art Wood Carving) who could impart this skill.

Lawrance taught wood carving at Leeds School of Art from 1911 and was ‘Special Craft Teacher in Wood, Marble and Stone Carving’ from 1923 to 1926. He had initially trained in London with Francis Child, an accomplished wood carver who was a senior member of Farmer and Brindley’s workshop. There is further information about Lawrance online at Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951, Glasgow 2011, http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/person.php?id=msib5_1213815016&search=john%20lawrance , accessed 10 September 2013.

There is a useful discussion of how stone should be bedded in Alec Miller, Stone and Marble Carving, Berkeley 1948, pp.22–3.

Catalogues and books associated with these exhibitions include: Exhibition of the works of Ivan Meštrovic, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Summer 1915; Exhibition of Serbo-Croatian Artists: Meštrovic, Racki, Rosandic, Grafton Gallery, London 1917; Exhibition of Sculpture by T. Rosandic: Paintings by M. Racki and S. Popovic, Etchings by T. Krizman, Serbian Red Cross Society in Great Britain, October–November 1919; Milan Curcin, Ivan Meštrovic: A Monograph, London 1919.

See the numerous wartime articles on these themes in the Art Teachers’ Guild Record. This was the journal of the Art Teachers’ Guild of which Gostick was a member from about 1911.

See Constantin Brancusi, Adam and Eve 1921, oak and chestnut, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Victoria and Albert Museum, 1915, no.44; and http://www.mgb.org.rs/en/component/jwallpapers/picture/toma-rosandic/69 , accessed 10 September 2013.

William Rothenstein bought a semi-derelict farm at the village of Far Oakridge in 1912 and William and Eve Simmonds bought ‘The Firth’ in 1919. See John Rothenstein, Summer’s Lease: Autobiography 1901–38, London 1965, pp.14–15 and information in Tate Archive TGA 9329.

More information about Simmonds is available at http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/william-g-simmonds-1942 and Glasgow 2011, http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/person.php?id=msib2_1208259787&search=simmonds , both accessed 10 September 2013.

William Rothenstein, letters to William George Simmonds, 21 April 1921, pp.1–2, and 26 July [1924], pp.1–2, Tate Archive TGA 9329.

More information about Oakley is available at http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/person.php?id=msib2_1220276782 , accessed 10 September 2013.

Hepworth and Skeaping lived at 7 Mall Studios from 1927 and Moore and Irina lived around the corner at 11A Parkhill Road from 1929.

K. Parkes, The Art of Carved Sculpture, 2 vols, London 1931, vol.1. In addition to Oakley and Simmonds, he mentions (among others) Richard Garbe, Leonard Jennings, Edna Manley, Rosa Milward, Elisabeth Muntz, Henry Poole, Charles Wheeler and Harold Youngman.

Parkes identified 1924 as the first year when works in this material made an impact at the Royal Academy, ibid., vol.1, p.94.

‘Wood as a Sculptors’ Medium’, 6 February 1931, Art Workers Guild. Alec Miller read the first paper. Durst spoke after the interval, followed by Ernest W. Gardner, Laurence A. Turner, Harold Stabler, Henry Paget, Matthew James Dawson, C. Thomas and T. Wilson. Art Workers Guild annual report, 1931, p.8 and http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/event.php?id=msib2_1219321248&search=Wood%20as%20a%20Sculptors%27%20Medium , accessed 10 September 2013.

This is discussed in detail by Andrew Stephenson in ‘Strategies of Display and Modes of Consumption in London Art Galleries in the Inter-War Years’, in Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich (eds.), The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850–1939, Manchester 2011, pp.98–125 and by Tanya Harrod in chapter three of The Crafts in Britain in the 20th Century, London and New Haven 1999.

Although Moore later distanced himself from all teaching contacts at the Royal College of Art, the work Durst was making at this time suggests the distance was, at least temporarily, not so great. The taut physical engagement of the figures in Durst’s The Acrobat 1927 (Tate T07903) recalls, as does Moore’s Standing Woman 1923, the work of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, although Durst’s carving possibly also looks to Leon Underwood in its stacked composition.

The gallery was set up in 1936 (see Harrod 1999, pp.133–5). There is correspondence between Moore and Dunbar Kilburn in Tate Archive. I am grateful to Alice Correia for drawing my attention to this.

‘Sculpture in the Open Air’, a talk for the British Council in 1955, in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, pp.97, 286.

For these designs see Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore: Sketchbook 1928, The West Wind Relief, exhibition catalogue, Much Hadham 1982, pp.56, 59, 60 and 61.

The stand of the Cotton Exhibition was in the Palace of Industry at the British Empire Exhibition (see Berthoud 1987, p.74).

Moore said: ‘I acquired samples of wood from the Commonwealth Institute which were being discarded by the Natural History Museum, where I knew the Director. They were examples of wood from many of the British colonies. I wasn’t told the name of this wood so could only call it dark African wood.’ Levine, Mitchinson and Moore 1983, pp.62, 78. The works in question are Torso 1927 (African wood), Figure 1932 (lignum vitae) and Composition 1932 (dark African wood). This information is a little confused. The Imperial Institute only changed its name to the Commonwealth Institute in 1958 long after Moore had ceased to make small sculptures in exotic woods and no direct connection between the artist and the Natural History Museum in the 1920s or 1930s has been traced. Both Lieutenant General William T. Furse (director of the Imperial Institute from 1926 to 1934) and his successor, Sir Harry Lindsay, gave timber samples to the Victoria and Albert Museum where Moore had several contacts. The other obvious possibility is that Furse became a member of the Board at Chelsea School of Art in 1931–2, when Moore joined the teaching staff. The spare samples of wood may have been offered to the Sculpture Department at Chelsea.

Observer, 17 April 1932, quoted in Nigel Vaux Halliday, More than a Bookshop: Zwemmer’s and Art in the 20th Century, London 1991, p.102.

Evelyn Silber, ‘The Leicester Galleries and the Promotion of Modernist Sculpture, 1902–75’, Sculpture Journal, vol.21, no.2, 2012, p.133.

Stephenson 2011, pp.199–20. There was a Yorkshire-London connection between Moore and Peter Gregory. Gregory’s Lund Humphries printing presses were located in Bradford, while he ran the business from London.

Legros was Slade Professor of Fine Arts at University College London. He gave Torso to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1891 (378-1891). See http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O138802/torso-of-a-woman-torso-legros-alphonse/ , accessed 10 September 2013.

Woodford and Evans respectively began their three-year Rome Scholarships in 1922 and 1923. Moore would have met them and seen work in progress in their studios on his visit to the British School at Rome in 1925. The classical fragments from the British Museum include Torso of a Youth (kouros), Greek, c.520 BC, marble (GR 1887.8–1.1), illustrated by Garrould, Friedman and Mitchinson 1982, p.52.

This work was carved in a piece of sycamore that was originally about 76 x 45 cm (see Levine, Mitchinson and Moore 1983, p.66).

Henry Moore, letter to Cecilia Dunbar-Kilburn, 26 August 1927, Tate Archive TGA 8424.69, quoted in Anne Middleton Wagner, Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, New Haven and London 2005, p.93.

This is widely documented. See, for example, Jennifer Mundy, ‘Comment on England’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, pp.22–37.

Arthur Mee, The King’s England: Kent: The Gateway of England and its Possessions, London 1936, p.30. The church of St. Nicholas, Barfreston, is an important surviving example of the English Romanesque and is decorated by extremely fine carvings.

See, for example, British Pathé titles relating to crafts in the southeast of England: ‘Basket Men of Sussex’, 1929, http://www.britishpathe.com/video/basket-men-of-sussex/query/basket+making ; ‘Along the Stour’, 1929, http://www.britishpathe.com/video/stills/along-the-stour ; ‘Cockles to Chuckles’ 1936, http://www.britishpathe.com/video/hoops-issue-title-is-cockles-to-chuckles , accessed 11 September 2013.

See ‘The Chiltern Bodgers.mp4’, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nP5_OJxNccY , accessed 11 September 2013.

Between 1934 and 1939 Moore made eight sculptures in elm, three of these were not included in Read 1944. These are Hole and Lump 1934, Family 1935 and Carving 1936 (nos.22, 23 and 29 in Levine, Mitchinson and Moore 1983). This more complete listing of his works in elm emphasises the importance of this material for Moore from the mid-1930s and adds to our understanding of how his approach to this type of wood evolved. It is not clear why the three sculptures in elm were omitted in 1944. Moore had technical difficulties with Family and had to add in a brace and so this may account for it being left out. It is also worth noting that Three-Piece Carving 1935 (ebony, no.19 in 1983) was also missing from the 1944 catalogue.

Roger Champion, former curator at the Weald and Downland Museum, provided helpful background information on the use of elm and how it is worked. I am grateful to Guy Viney for putting us in touch. The account of Dutch elm disease is based on Oliver Rackham, The History of the Countryside: The Full Fascinating Story of Britain’s Landscape, London 1986, multiple references in The Times Digital Archive 1785–2006 and the archives of Chelsea Polytechnic, Archives and Special Collections, King’s College, London. A documentary about wheel making can be found at http://www.eafa.org.uk/catalogue/700 , accessed 9 June 2014. This process is also described in George Sturt, The Wheelwright's Shop, Cambridge, 1923, see especially the chapter on 'Stocks' (the term used by Sturt for a nave or hub).

Shelley Faussett (son of the poet Hugh l’Anson Faussett), who was Moore’s first post-war assistant c.1945–8, in an interview with Roger Berthoud, February 1984, in Berthoud 1987, p.433 note 4.

This did not always work smoothly. The fourth elm figure of 1959–64 revealed a crack in the trunk that had not been visible initially but by carving it very slowly the problems were eventually overcome.

For Regenesis see Ben Whitworth, The Sculpture of Leon Underwood, London 2000, no.38, pl.2; and for Three in One see Jane Hill, The Sculpture of Gertrude Hermes, London 2011, no.33, fig.53.

The Zadkine, affectionately known by the family as ‘the old girl’, was an eye-catching feature in the garden and an important symbol of a commitment to abstract art. Myfanwy Piper remarked on this in relation to a visit to Maresfield seeking support for the magazine Axis: ‘It was already an encouragement to see the Zadkine standing among the trees and grass as we drove up. It made our interest in post-impressionist and abstract art seem more normal instead of a rather absurd and impractical whim.’ Barbara Wadsworth, Edward Wadsworth: A Painter’s Life, Salisbury 1989 p.214.

Based on correspondence from Zadkine to Moore in the Henry Moore Foundation Archive, Wadsworth 1989, pp.163, 191, and Levine, Mitchinson and Moore 1983, p.21.

This is the title given to this work in Ionel Jianou, Zadkine, Paris 1964. However, it is not clear whether this was Jianou’s description of the piece or a title given to it by Zadkine.

Moore already had another work in an American public collection: Two Forms 1934 (pynkado wood), Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Not all the sales of the reclining figures progressed smoothly. The committee at Wakefield took several years to accept Moore’s offer of a reduced price and to take up financial support from the Victoria and Albert Museum and from Peter Gregory, which together covered most of the acquisition cost (see Berthoud 1987, p.141).

Bought by Curt Valentin, Moore’s dealer in New York, in 1946. In 1952 Valentin sold the piece to Cranbrook Museum for $6,000 on the recommendation of the sculptor William McVey. It was sold by Cranbrook at Sotheby’s, New York, for $260,000 in 1972 and bought by Fischer Fine Art. The gallery sold it to an Italian businessman, who in turn sold it at Sotheby’s, New York, in 1982 for $1,265,000 (£647,740). Thomas Gibson, a London dealer, acquired it and sold it the same day for an additional 10% to Wendell Cherry, Louisville collector and head of Humana hospital group. Cherry loaned the work to the J.B. Speed Art Museum, Louisville (see Berthoud 1987, pp.198–9).

Jacquetta Hawkes, A Land, with drawings by Henry Moore, London 1951. I am grateful to Andrew Causey for pointing out that Hawkes intended there to be images by other artists including Ben Nicholson and Paul Nash but ran into difficulties with copyright and so the edition of 1951 only has the two pictures by Moore.

The most extensive discussion of this connection is Penelope Curtis and Fiona Russell, ‘Henry Moore and the Post-War British Landscape: Monuments Ancient and Modern’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, pp.125–42.

Among the accounts of funerary sculpture in wood were: A.H. Church, ‘English Effigies in Wood’, in A.H. Church (ed.), Some Minor Arts as Practised in England, London 1894; Alfred C. Fryer, Wooden Monumental Effigies in England and Wales, London 1910 (revised edition 1924), and Alfred Maskell, Wood Sculpture, London 1911. The record of Moore’s parents marriage is found in West Yorkshire Archive Service, Yorkshire Parish Records; New Reference Number: RDP76/3/4.

John and Myfanwy Piper’s trips around Britain to photograph early carvings in 1935–6 are described in Frances Spalding, John Piper, Myfanwy Piper: Lives in Art, Oxford 2009, pp.72–4.

The type of armour worn by the figure dates from 200 years after the last member of the family with the name Johan de Hauteville. It is now thought to be of Sir John Wych. See http://churchmonumentssociety.org/Somerset.html#Chew_Magna_-_St_Andrew , accessed 10 September 2013.

Ann Compton is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Glasgow.

How to cite

Ann Compton, ‘‘An essentially different kind of rhythm’: Rediscovering Henry Moore’s Sculpture in Wood’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www