Henry Moore and Concrete: Cast, Carved, Coloured and Reinforced

Judith Collins

Moore used concrete, a material then associated with modernist architecture, to make sculptures between 1926 and 1934. This essay explores the corpus of his concrete work and relates it to his wider practice.

Henry Moore made in total twenty-one sculptures in concrete, all between the years 1926 and 1934. This was a period of experimentation and rapid development in his career in which he explored this new medium alongside stone and wood. As he later commented, he was then very interested in all types of sculptural media and took up concrete in part because it was becoming a more commonly used building material and he was hopeful of being commissioned to produce concrete sculptures to go with these new buildings.1 Perhaps equally important was its cheapness (he had little money then) and the different ways in which it could be worked: concrete could be cast in a mould, shaped and added to while soft, or carved when hard. It could also be coloured by pigments and incorporate other objects. Carving was his preferred mode of making sculptures during the 1920s and 1930s: famously espousing the doctrine of truth to materials, he publicly championed the view that a sculptor should carve word or stone directly in order to be able to respond to its properties rather than attempt to disguise them. But the story of Moore’s engagement with concrete shows him also alive to the possibilities of a material that could be modelled, carved and cast, and creates a more nuanced understanding of his approach to material and technique in the interwar years.

Concrete is a material invented by the Romans. It consists of a binder and a filler which, when mixed together with water, hardens. The binder is gypsum, lime or volcanic dusts such as tufa and pumice, while the filler is a range of aggregates, such as brick and ceramic rubble, ground rock and fine gravel. The quality of the aggregate affects the texture of the concrete, while its colour can be altered by the addition of pigments. After the fall of the Roman empire concrete was no longer used and only re-emerged in the nineteenth century with the invention of Portland cement in 1824. In the 1900s French architects Auguste Perret and François Hennebique pioneered the use of reinforced concrete as a building material, embedding steel bars in concrete before it set. The modernist architect Le Corbusier, who for a period worked for Auguste Perret, used reinforced concrete in his buildings in the late 1920s. One of the first examples of the use of reinforced concrete in Britain were the Lawn Road flats in Belsize Park, London, also known as the Isokon Building, designed by the architect Wells Coates and completed in 1934. Moore lived nearby and was a friend of Wells Coates, so would have been well aware of this new use of concrete. Interviewed by his photographer friend John Hedgecoe in 1968, Moore recalled, ‘At the time reinforced concrete was the new material of architecture. As I have always been interested in materials, I thought I ought to learn about the use of concrete for sculpture in case I ever wanted to connect a piece of sculpture with a concrete building.’2 He was not to get an opportunity to produce a concrete sculpture for a concrete building, but his decision to explore the medium reflected his interest in contributing to new architectural projects.3

Moore, of course, was not the first to use concrete as a material with which to make art. European artists began to employ it just before the First World War and then again in the early 1920s. German artist Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881–1919), for example, created portrait heads and figures in a type of concrete in 1911–18, when he lived and worked in Paris and then Berlin. He added stone dust to cement powder and, mixing this with water, poured the mixture, which was described as ‘cast stone’ or ‘cement’, into moulds. The reason Lehmbruck turned to concrete is not known but it is most likely because it was freely available and inexpensive. The same motive could have applied to the Ukranian artist Alexander Archipenko (1881–1964), who lived and worked in Paris. In 1913 he made a large concrete figure called Bather. This was illustrated in the first monograph on the artist, published in 1923, a copy of which Moore owned. Hungarian artist Peter Peri (1899–1967) worked as a stonemason in his teens, before moving in 1920 to Vienna, Paris and Berlin. He joined a group of exiled left-wing Hungarian avant-garde artists, the most prominent of whom was László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946) who was a forceful advocate of the integration of art and modern technology. At a joint exhibition at the Der Sturm Galerie, Berlin, in February 1922, Moholy-Nagy showed paintings and metal sculptures while Peri showed abstract geometric reliefs, mostly made from concrete. Peri also modelled some figures in concrete to which he added colour. After he moved to London in 1933, Peri continued making small concrete figures and reliefs using mortar (a mix of sand and Portland cement) and trowelling the mix onto shaped metal mesh. Another artist working in Britain that might be mentioned in this context is Loris Rey (1903–1962), who studied and briefly taught at Glasgow School of Art between 1923 and 1926 and was Head of Sculpture at Leeds College of Art from 1927 to 1934. He produced a concrete mother and child sculpture that was bought by the influential collector (and patron of Moore) Sir Michael Sadler. Moore was thus not alone in seeing the potential of concrete as a sculptural material but it remained an uncommon choice.

When Moore began to experiment with concrete, there were two types of cement powder or binder available to him. The most common brand was Portland cement, which is greyish in colour and made from a mixture of ground limestone and clay deposits found on the isle of Portland, near Weymouth in Dorset. Portland cement powder, when mixed with water, sets within the hour under normal conditions, cures in just over a week, and reaches maximum hardness in a month. The second, more expensive, type was a French invention called ciment fondu, a high aluminium content cement made from a mixture of limestone and bauxite. This has a setting time of two hours, reaches full strength in twenty-four hours and does not suffer from shrinkage. Moore made at least two works with this type of material: Half – Figure and Reclining Figure, both illustrated in sculptor John Mills’s book Sculpture in Cement Fondu (1958), with their medium described as ‘aluminous cement’. The fillers available to Moore were a range of fine to coarse gravels, and other materials such pulverised seashells, pumice, marble dust and sand. Moore experimented with a range of aggregates, some of which were angular particles, while others were more rounded. The success of his pieces depended on his ability to choose the right consistency of concrete for the chosen shape, and the right amount of aggregate so as not to overwhelm the surface qualities of that shape.

In 1926, as Moore began to make sculptures in concrete, he also began to consider the idea of ‘truth to material’. The concept first emerged in texts about art and design at the end of the nineteenth century, which argued that properly designed objects should be honest in how they presented themselves, celebrating the qualities of the materials from which they were made and not pretending to be something they were not. Moore became a passionate advocate of this principle, writing in Unit One in 1934: ‘Every material has its own individual qualities. It is only when the sculptor works direct, when there is an active relationship with his material, that the material can take its part in the shaping of an idea.’4 Critics seized upon such comments as a means of explaining the sometimes geometric, sometimes organically curvilinear forms of his stone and wooden pieces, as if the materials had themselves determined the shapes of his works. Concrete, however, could not be said to have inherent shape properties (though its texture and colour are potentially distinctive), and Moore’s twenty-one concrete works give the lie to a view that he was so committed to the doctrine of truth to materials in the interwar years that he did not explore other media.

Moore does not seem to have been moved to talk publicly about his use of concrete: through his life he talked about carving stone and wood with great affection but he rarely talked about his use of the manufactured material. The two leading commentators on Moore’s sculpture, Herbert Read and David Sylvester, also did not mention his concrete sculptures, except in passing. For Moore, learning to use concrete was perhaps simply something he attempted on the off chance that he might want ‘to connect a piece of sculpture with a concrete building’.5 In 1934, he was offered the experience of creating a sculpture for a new building in London, but the building was made from Portland stone and not concrete, and he was never able to put his experience to work in the context of an architectural commission. In short, his knowledge of working with concrete was never put to the test, which perhaps explains his lack of communication on the subject.

The sequence of Moore’s twenty-one concrete sculptures begins in 1926 with cast works and progresses in 1932–4 to works that were built up on a metal armature and then carved into shape. When he was interviewed by his friend, the photographer John Hedgecoe, however, he recalled the sequence differently: ‘The first method of using concrete I tried was building it up on an armature and then rubbing it down after it had set. This I had to do very quickly because the cement and the gritty aggregate mixed with it set so hard that all my tools used to wear out. Secondly I tried casting in concrete.’6 Assuming Moore’s is correct here, why are the earliest surviving works cast rather than modelled? Perhaps he never completed his very earliest pieces or destroyed those he did. The speed with which he was forced to work and the damage to his tools caused by setting concrete may also have led him to choose to experiment with casting and carving, rather than modelling. As will be seen, casting proved particularly fruitful for him, and accounts for thirteen of the known twenty-one concrete works.

In the first catalogue of his sculpture and drawings, published in 1944, Moore chose to organise his three-dimensional works according to the material used: stone, terracotta and concrete, wood, stringed figures and metal. The largest section was, predictably, that of stone, with 115 works, while the terracotta and concrete section comprised nineteen works made between 1923 and 1934. Of these thirteen were made of concrete, four of terracotta, and there were also two reliefs made from wood, plaster and gesso. The full list of twenty-one concrete works was not made public until the publication of a revised edition of the catalogue, compiled with the assistance of David Sylvester, in 1957. Here Moore chose to have his sculptures listed simply in chronological order, though he cared sufficiently to distinguish the four different ways that he had worked with concrete, describing works as ‘cast concrete’, ‘carved concrete’, ‘stone and carved concrete’ and ‘carved reinforced concrete’. The latter three are all built up on armatures.

Moore’s thirteen ‘cast concrete’ works, required concrete to have been poured into a plaster mould and left to dry and cure. Once set, he would have chipped away the plaster to reveal the concrete form inside or carefully pulled the sectioned piece mould apart. (A plaster mould is created from a modelled clay original, divided into sections by the use of clay or thin brass walls, known as shims. This technique allows the plaster mould to be removed from the original in pieces. The divisions leave slightly protruding seams or joins where the piece fitted together, and these are visible on many of Moore’s concrete sculptures).

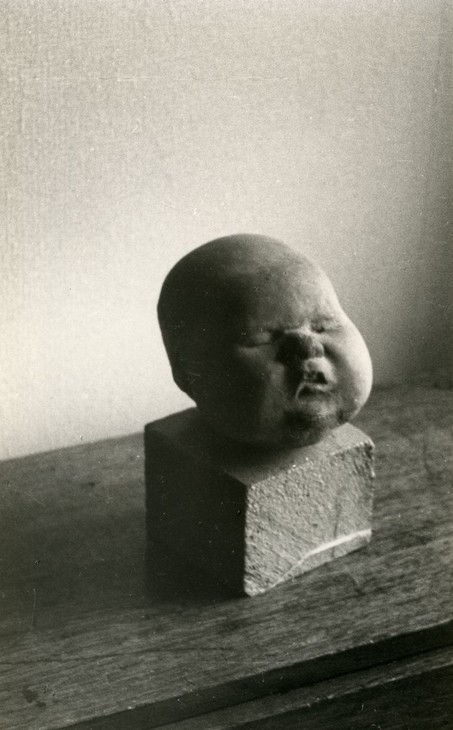

Moore’s first cast concrete sculpture was made while he was staying with his sister Betty and her husband Rowland Howarth, who in 1922 had been appointed head teacher of Mulbarton village school, near Norwich, Norfolk. The Howarths’ second child Mary was born at their home in April 1926 and so when Moore came to stay in July she would have been around three months old. He modelled her head from life, presumably in clay, and made a plaster mould from the clay, into which he poured liquid concrete. Since the head (fig.1) is small, it is likely that it is a solid rather than a hollow cast. Moore would not have needed to use granular aggregates to bulk up the form and they would have given the tiny face too much texture. Baby’s Head is set on a cube of concrete just larger than the head itself. Although this was a very personal work, made for a close family member, Moore chose to include it in his first solo show at the Warren Gallery in 1928, where he gave it the title Little Girl. It has not been exhibited since.

Henry Moore

Baby's Head 1926

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Baby's Head 1926

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

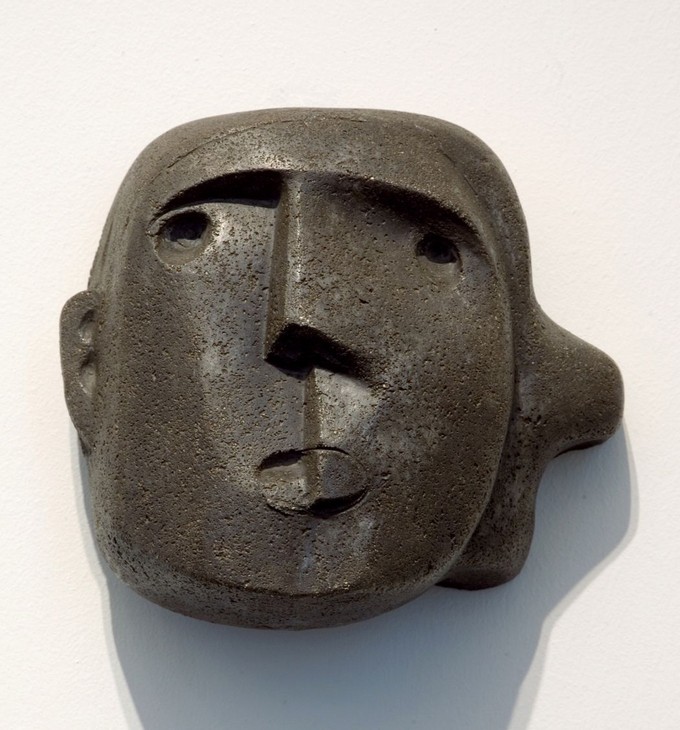

Henry Moore

Head of a Woman 1926

Concrete

The Hepworth Wakefield

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Norman Taylor

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Head of a Woman 1926

The Hepworth Wakefield

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Norman Taylor

Made around six months later, Moore’s second cast concrete work was also a female head (fig.2). In 1925 Moore had spent six months in Italy on a travelling scholarship, visiting Florence, Siena, Assisi, Ravenna and Padua among other places, to look at Renaissance works of art, even though he had already become passionately interested in Sumerian, Egyptian and Pre-Columbian art. The two Italian artists who most impressed him were the painters Giotto and Masaccio. In a letter he described Giotto’s painting as ‘the finest sculpture I met in Italy’, while he was enthralled by the grandeur and simplicity of the figures in Masaccio’s frescoes in the Brancacci chapel in the Carmelite church in Florence.7 Head of a Woman has much in common with the figures of both painters, although the long nose and small lips are also reminiscent of carved limestone heads of the modern Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani (one, made in 1911–12, was presented to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1922). Moore’s sculpture was also one of the earliest of his heads to have what the critic David Sylvester called Moore’s ‘cubic bun’, at the back or side of the head.8 A page in Moore’s sketchbooks, datable to 1925–6, shows seemingly related images of four heads, with buns.9 This sculpture is set on a wooden base, making it unique among his concrete works. It is worth noting that his remaining nineteen concrete works are set on integral bases.

Moore showed Head of a Woman in his exhibition at the Warren Gallery, London, in January 1928, and then sent it to the Yorkshire Artists’ Third Exhibition at Leeds City Art Gallery in January 1930. Here a reviewer compared it to the painting North Sea by another Yorkshire artist, Edward Wadsworth, writing that the Moore sculpture had ‘the same impassivity and coldness as the Wadsworth painting’. ‘In addition its planes are distorted in a fashion which may repel the less adventurous eye.’10 Certainly the eyes can be described empty ovals but distorted planes are not that evident. The reviewer made no mention of the use of concrete.

Moore’s first figure in concrete was a nude female presented from neck to mid-thigh (fig.3). The pose was angular, with the left shoulder lifted high and the arm partially hiding one of the two hemispherical breasts. By 1926 critics were noting that Moore’s style was nourished by his admiration for world art (or primitive art as it was then often called) but this figure has something of the flavour of the current European art deco movement. It specifically echoes the contrapuntal rhythms of the small nude female figures made in these years by Alexander Archipenko (1867–1964) and Ossip Zadkine (1890–1967). Moore paid regular visits to Paris in the 1920s and would have seen what these two artists were making. P.G.Konody, art critic for the Observer, reviewed Moore’s Warren Gallery solo show in January 1928, which included Torso, and stated that some of the works in the show ‘derived from intercourse with such Continental sculptors as Zadkine and Archipenko’.11 A preparatory drawing, Ideas of Sculpture: Torso 1925, is in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada.

Henry Moore

Torso 1926

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Torso 1926

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Henry Moore

Mask 1927

Cast concrete

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Mask 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

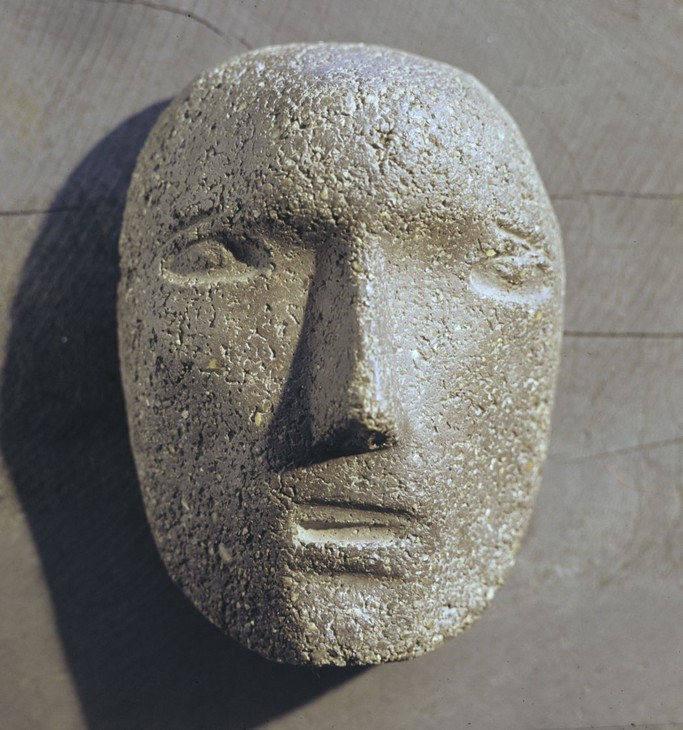

The small work Mask 1927 (fig.4) was the second mask Moore made. Like his first, carved from Verde di Prato stone in 1924, this one was inspired by Mexican stone masks in the British Museum. He gave it an open mouth, as though singing or speaking. Leon Underwood (1890–1975), painter, sculptor, printmaker and writer, bought this mask from Moore. Underwood was a tutor at the Royal College of Art when Moore was a student there, and Moore described him as the only person there who taught him anything.

Suckling Child (fig.5) is the largest of the four concrete works made in the summer of 1927. Nothing prepares the viewer for the unprecedented image of a child suckling on a disembodied pair of breasts. The mother’s body is reduced to a small chunk of torso and breasts, and the viewer of this now lost work was invited to view the sculpture from the position of a mother looking down on her suckling child. The work was the third Moore had made on the theme of the mother and child, a theme that was to obsess him throughout his working life. The first example, Mother and Child, was carved from stone in 1922, while the second, Maternity 1924, depicted a half-length female holding a suckling child to her breast. Moore’s admiration for, and knowledge of, the carved stone works of the sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska may have played a role here as he may well have known of Gaudier-Brzeska’s treatments of the theme: one work, Maternity 1914, sometimes called Charity (Musée des Beaux Arts, Orleans), shows a standing nude female offering her breasts, at which two small children suckle greedily.

When first exhibited at the Warren Gallery in 1928, Suckling Child had already been bought by the American sculptor Jacob Epstein, who encouraged and supported Moore. It was the work most singled out for comment in the show. Writing in the Observer, P.G.Konody felt that, ‘Mr Moore is at his best where he approaches realistic treatment, as in the “Suckling Child” ... which is realized with passionate intensity.’12 A reviewer in the Times review commended Suckling Child ‘for its immense vitality’.13 The Daily Herald resorted to hyperbole in its headline: ‘Miner’s Son as Artist. Sculptures that are Staggering. His Genius’, and described this piece as ‘superb’.14 The Morning Post reviewer, however, felt that the head of the baby in Suckling Child was ‘admirably modelled, but the mutilated breast of the woman is revolting15.’ As before, no reviewer drew attention to Moore’s use of concrete.

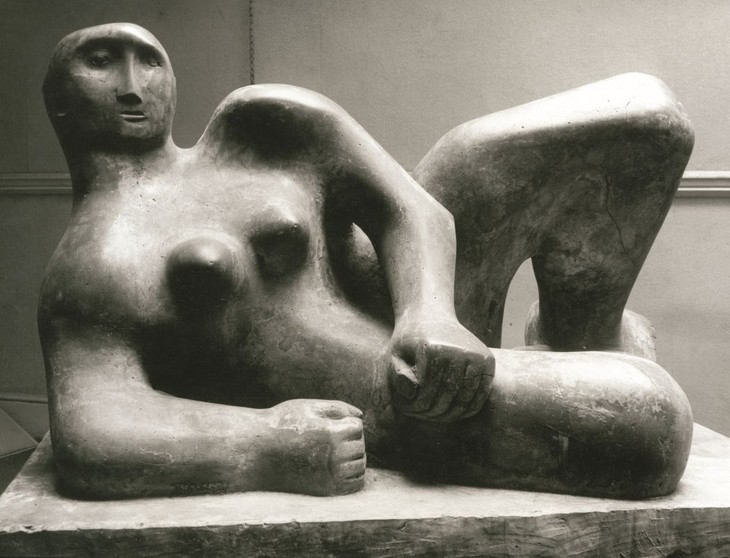

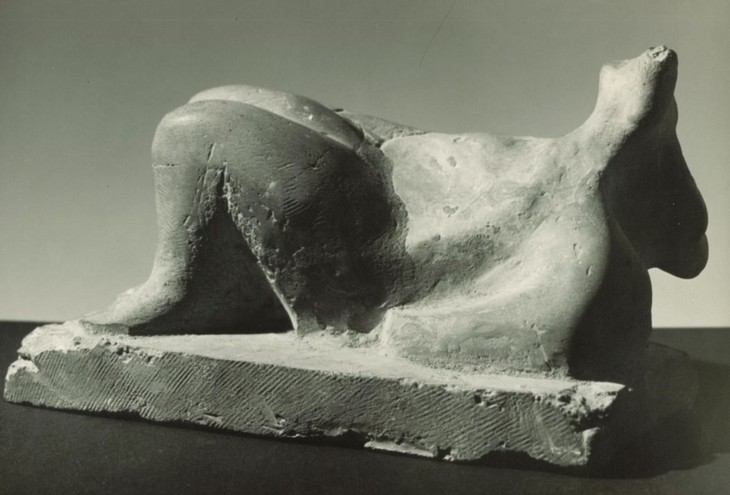

Although not the first reclining woman by Moore, Reclining Woman 1927 (fig.6) is the earliest piece on this theme to survive. Made in 1927 and first exhibited in his Warren Gallery show in January 1928, it occasioned comment only in June 1929 when it was included in a group exhibition of the Sandon Studios Society at the Bluecoat Studios in Liverpool. Here it received a detailed and sympathetic review from George Whitfield in the Liverpool Echo in an article titled, ‘The Curved Lady in Concrete’. This was the first review to discuss Moore’s use of concrete as a material, and to praise him for using it. Whitfield began:

it was rather like genius for the artist to have his woman cast in concrete. The sculpture is sufficiently modernistic to be as old as Eden, while concrete, although one finds it in the structure of the Coliseum, is a material reaching its heyday in modern times. Moreover, concrete, by its very limitation of manipulation, enforces a reduction to bare essentials, and, by its rock-like character, well befits a work of art which depends completely for its primitive truth upon simple Euclidian statement and demonstration. True, the surface texture is rough, like pumice stone; but, again, one feels that for such a work a relationship to volcanic origins is scarcely out of place. In fact, by reaction to the very stuff of his material the artist has been moved (through a force exterior to himself) to bring the softness of ample flesh to his woman of stone. The breasts are obvious proof. Stone they may be, yet they would, you feel, dimple at the touch. So, in a lesser degree, would the huge, but female, shoulders and arms. The great hip, too, and tremendous thighs.16

Whitfield related the reclining figure to the volcanic origins of some of its material constituents, which must be one of the first critical statements to link Moore’s figures with the landscape and specifically with mountains and valleys, a connection that would become a leitmotif in writings about Moore’s reclining figures.

Evocative of a small toy, Duck 1927 (fig.7) looks back to Moore’s earlier animal pieces (for example, his alabaster Dog 1923, coiled marble Snake 1924) and is a companion to his small polished bronze Bird, made around the same time. Two sculptors close to Moore at this time, Barbara Hepworth and John Skeaping, were also making sculptures of stylised animals and birds, and it may be that three of them found it easier to work towards abstraction using these subjects rather than the human figure. The animal figures of all three sculptors, however, owe something to the carved and modelled animals made by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska in London on the eve of the First World War, including a pair of alabaster Stags, a marble Fawn, a Dog in cast aluminum and, most significantly in relation to this piece, a small marble Duck. Gaudier-Brzeska pared his duck to a set of geometric forms and here Moore has taken a similar approach but added an odd base that resembles a doorstop. For reasons that are unknown Moore showed a bronze cast of Duck, rather than the concrete version, at his Warren Gallery show in January 1928.

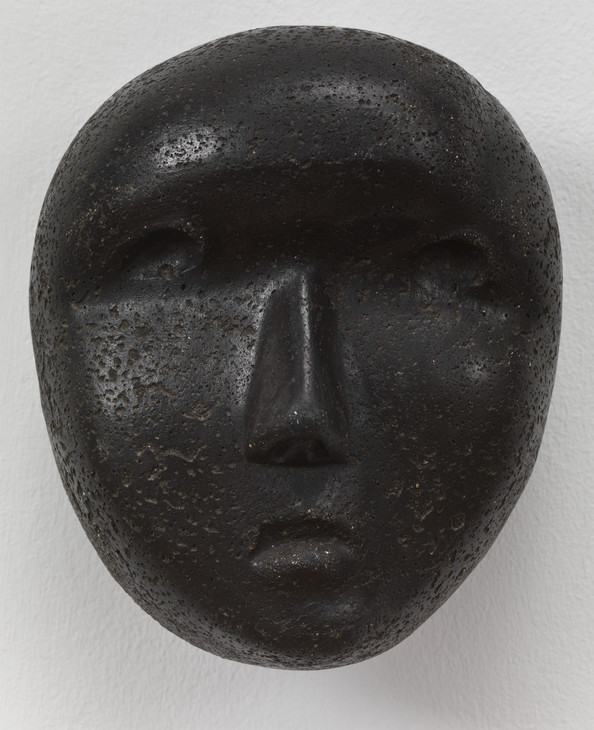

Henry Moore

Mask 1929

Cast concrete

240 x 210 x 123 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Mask 1929

Leeds Museums and Galleries

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Mask 1929

Cast concrete

object: 200 x 180 x 130 mm

Tate T03762

Transferred from the Victoria & Albert Museum 1983

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore OM, CH

Mask 1929

Tate T03762

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Of the eighteen sculptures Moore made in 1929, six were masks. Three of these were made from stone and three from concrete. He acknowledged that his interest in masks was stimulated by L’Art précolombien (1928) by Adolphe Basler and Ernest Brummer, which he bought in Paris in the year when it was first published. This particular mask was inspired by a fourteenth-century Aztec basalt mask depicting the god Xipe Totec found in the British Museum. The stepped vertical line running roughly from forehead to chin suggests two separate views of the face, in much the same way as could be found in a cubist painting. It is known that Moore started to add coloured pigments to his concrete sculptures in 1929.

Mask (fig.8) was bought by art historian Sir Philip Hendy, a friend of Moore who was Director of Leeds City Art Gallery (1934–46) and of the National Gallery (1946–1967). It was acquired by Leeds City Art Gallery in 1983. Of the concrete masks Moore had made to date, Mask (fig.9) was the most sober and possibly tender in mood, with the least distortion and departure from symmetry. The eye sockets may have been created by pressing a thumb into soft clay. The work’s appearance is similar to that of wooden masks made by the Dan tribe, found in Liberia and the Ivory Coast. It has quite a dark hue, and it may be that Moore added black or grey pigment to the concrete mix to give this work the appearance of polished wood or basalt.

The way that the eyes and the mouth are articulated, seemingly cut into the original clay with a sharp tool, give Mask (fig.10) a quality of anguish or terror. Mixed in with the cement powder, the gravel aggregate is very apparent, with small stones pushed right to the surface of the face. The resulting uneven texture shows Moore’s willingness to embrace a lack of surface finish. This cast appears to contain some pigments of both greenish and reddish hues, making the cast look similar in colour to Ancaster stone.

Moore showed his three 1929 concrete masks (figs.8, 9 and 10) in his solo exhibition at the Leicester Galleries, London, in May 1931. For the New York magazine Art News critic Louise Gordon Stables found Moore’s materials unpleasant in colour and surface:

The use of concrete is interesting, but ... the tone of the concrete has not always been happily selected ... There is no doubt that with concrete establishing itself as the building material of the age, there is need for sculptors to arise to show us how carvings should be planned in relation to a concrete setting. Perhaps Mr Moore’s most valuable contribution to modern aesthetics will run along these lines, for his essays in concrete suggest that he eventually may become skillful in its handling.17

Henry Moore

Seated Figure 1929

Cast concrete

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Seated Figure 1929

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

in Sumerian art ... along with the abstract value of form and design, inseparable from it, is a deep human element. See the alabaster figure of a woman which is in the British Museum ... with her tiny hands clasped in front of her. It is as though the head and the hands were the two equal focal points of the figure – one cannot look at the head without being conscious also of the held hands.18

But Moore softened the pose, and thereby made it more contemporary, by opening the legs a little and imbuing the features with a certain anxiousness the Moore included Seated Figure 1929 in his Leicester Galleries exhibition in April 1931, where he described the medium as ‘brown concrete’. This indicates that he added a mid-brown pigment to the wet concrete, lending the work the hue of sandstone or wood. Moore may have wanted to personalise the otherwise rather anonymous material and relate it to his contemporary stone and wood carvings.

With massive arms and a stepped face that recalls the stylistic innovations of cubism, Moore’s Half-Figure 1929 (fig.12) is a half-length nude female, which stands with one hand resting on top of the other. An incised line, either created in the clay original or chiselled into the cast concrete, meanders down the front of the figure, beginning at her neck, passing between her breasts and ends by circling her navel. It is an echo of the many similar lines that Moore included in his imaginary figure drawings. Half-Figure was bought in 1942 by art collectors Robert and Lisa Sainsbury, who first met Moore in 1933 at his second show at the Leicester Galleries, London, and became regular purchasers of his work.

Henry Moore

Half-Figure 1929

British Council

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Half-Figure 1929

British Council

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1932

Location unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1932

Location unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Head 1932

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Head 1932

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Although abstracted, Composition 1933 (fig.16) can be seen as possessing aspects of the head and upper torso of a female figure. The large dimple at the top contains incised lines denoting perhaps an eye and a nose, while the two smaller protuberances below appear to be breasts, with the nipples rendered as concavities rather than as projections (a feature of Moore’s female figures from 1929). As with Head 1932 Moore tipped three different coloured pigments into the wet concrete mixture but did not stir them together.

More unusual were his ‘stone and carved concrete’ works. For these he would have selected a small stone or pebble and embedded it into a damp concrete mass, shaping the stone and concrete into an integrated whole. A nodule of flint or an ironstone pebble seems to have been used for the head and shoulders of this reclining figure, while the rest – the arms, torso and legs – was modelled in concrete. In the early 1930s Moore regularly turned to his ever-growing collection of pebbles, shells, driftwood and bones for new ideas. In 1934 he wrote: ‘The observation of nature is part of an artist’s life, it enlarges his form knowledge, keeps him fresh and from working only by formula, and feeds inspiration.’23 In his drawings he began to develop figures from the shapes of stones and bones, and with the stones and bones themselves he added pellets of plasticine or clay, casting the results in plaster, to create unexpected variations on the human figure. This may have encouraged him to take the previously unprecedented step of incorporating found pebbles in his sculptures. An example of this style, Reclining Figure 1932 (fig.17) was bought by the dealer Erica Brausen, who ran the Hanover Gallery in London.

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1932

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.17

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1932

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1932

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.18

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1932

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

It seems again that a nodule of flint served as the head and shoulders of Reclining Figure 1932 (fig.18). The work was bought at some point by American collector Joseph Hirshhorn, who acquired his first sculpture by Moore in 1945, and by the 1970s owned fifty-one pieces by the artist. This piece and the previous work are numbered 120a and 120b in Moore’s catalogue raisonné and thus appear to have been inserted into the numbering sequence at a late stage, possibly indicating that Moore had some doubts about whether to include them in the official catalogue of his work.

Made with concrete reinforced with steel rods, Reclining Figure 1932 (fig.19) was the grandest of Moore’s reclining figures to date, and his largest work in concrete. Moore was then working in a small studio in Parkhill Road, Hampstead. From contemporary photographs of the studio it is obvious that the space was not ideal for mixing and pouring large quantities of wet concrete. It therefore seems likely that this was made at Jasmine Cottage, his home in Kent, where he made sculpture during his summer holidays. The figure leans on her right elbow and raises her left knee, giving the pose several axes and many holes, arches and shadowed inner areas. The counterpoise of the pose gives the figure a sense of balanced solidity that is further emphasised by its attachment to the slab-like concrete base. Moore has added coloured pigments – red, brown and black – to the concrete mixture and chose not to stir them together in order to allow the colour to appear in random patches. There is little evidence of an aggregate being added to the mix.

Reclining Figure was purchased by Moore’s friend and patron Sir Michael Sadler, who was Master of University College, Oxford, from 1923 to 1934. At some point before December 1933 he sited the work outdoors in his garden at Headington, just outside Oxford. Sadler was keen to ensure that the concrete sculpture would fare well in his garden, and had discussed this with Moore. In a letter to Sadler, dated 31 December 1933, Moore reported that he had recently met with ‘an analytical chemist, working for a firm of paint manufacturers’, who told him that many new concrete buildings ‘showed a tendency to be affected by the weather, and over large flat areas tiny hair cracks might appear’. The chemist thought it would be wise to cover the sculpture with his preparation ‘which is thin and transparent and does not alter the look of the surface’ since ‘nobody yet knows enough about the durability of concrete’.24 Moore sent a tin of the solution to Sadler in February 1934, and a local man painted it on the work. The sculpture was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1946 and was acquired by the City Art Museum, St Louis, Missouri, in 1948.

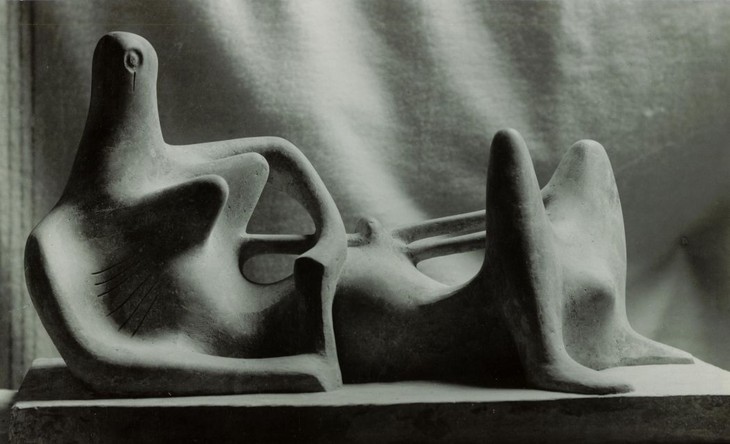

In 1931 Moore made a drawing in ink and wash titled Drawing for Figure in Metal or Reinforced Concrete (private collection). This showed a reclining female nude with a thin left arm and a number of rod-like forms joining her torso to her left leg – forms that could only be made in metal, either cast in lead or bronze, or as rods hidden under thin layers of concrete. This drawing marked the beginning of Moore moving away from his large blocky forms towards more linear sinuous shapes, and the first sculpture to display these characteristics was a lead cast, Reclining Figure 1931, which had three rods-like forms set across the hollow in the torso, suggesting a ribcage.

In 1981 Moore spoke to Franco Russoli about his adoption of lead in 1931:

The lead figures came at a stage in my sculpture career when I wanted to experiment with thinner forms than stone could give, and ... in metal you can have very thin forms ... I couldn’t afford in those days to make plasters and have them cast into bronze ... But I could mould lead and do the casting myself and it was soft enough when cast to work on it and give a refinement; I could cut it down thinner, and finish the surface, so for me lead was both economically possible and physically more malleable.25

Reclining Figure 1933 (fig.20) was a bold attempt to express in concrete some of the ideas of the 1931 drawing and lead piece. The figure describes an undulating curve, rising and falling, from head to feet. Horizontally placed metal rods link the torso with the raised knees. This use of thin rods to traverse the space between two forms can be said to prefigure Moore’s series of stringed works of the late 1930s.

When Moore included this concrete piece in his second solo show at the Leicester Galleries in November 1933, it provoked an enthusiastic response from the critic Adrian Stokes in the Spectator:

Here are the peaks of feminine form, realized at last freely, with the aid of mere connecting rods; here as twin summits stand the tall cylindrical knees; here as dolmens are the breasts; here the topmost plateau of the head; while so uniform and simple are the links between these forms that the composition as a whole may suggest an image of Cleopatra reclining in the stern of an Egyptian barge, her long body in such unison with the boat that her propped-up head, as though the topmost section of a rudder oar, guides, steers, and governs.26

Moore included this work, along with three other sculptures, in the International Surrealist Exhibition, held at the New Burlington Galleries, London, in June 1936.

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition 1934

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.21

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition 1934

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The last work Moore made from concrete, Four-Piece Composition 1934 (fig.21), seems to have been made largely from cement (there is little evidence of aggregate). The title simply enumerates its elements but the work can still be read as a figure of sorts. The multi-part and horizontal nature suggests the influence of the Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966), newly part of the surrealist movement in Paris, but the piece has little or nothing of the sense of violence found in the latter’s work. Moore’s composition looks more like an assemblage of found natural objects, bones and pebbles. He was breaking up the human body into parts so that it could be explored from every angle. There is little sense of dislocation; rather there is a sense of positive enquiry. The pierced disc brings to mind the Mên-an-Tol prehistoric stone monument in Cornwall (fig.22) that was so influential for Barbara Hepworth and her work.

The years in which Moore worked with concrete were his years of experimentation with materials and processes. At times it appears Moore wanted his concrete sculptures to look like stone, and perhaps he was using it simply as a substitute for the more expensive material. But he was also intrigued by its texture and potential to be coloured. In 1929 he used Roman travertine, a non-indigenous stone, for a carved sculpture called Figure with Clasped Hands, and later told his friend John Hedgecoe how much he liked its colour and its rough, broken pitted surface. That same year Moore made six concrete works – three masks and three small figures – all of which had pitted surfaces that resembled travertine.

There does not appear to have been any impetus, apart from personal preference and financial considerations, for Moore to choose to work with concrete. The sizes and subjects of Moore’s concrete sculptures were the same as for his works in other media; he did not make his concrete works a separate or unique category, and his friends and admirers purchased concrete works as much sculptures in wood, stone or metal. Significantly, Moore was particularly keen in the interwar years to work with a wide range of British stones. Rejecting the traditional white Italian marble he had been obliged to work with at the Royal College of Art, he found examples of coloured and textured British stones in the Natural History Museum and acquired examples of those that appealed to him, including Green, Brown and Blue Hornton stone, Ancaster stone, and Hopton Wood stone. Beyond their colour and texture, however, he particularly liked the fact that no-one had previously used these stones for sculpture. Seen primarily as a building material, the unusual stones thus offered him the opportunity to be a pioneer in their artistic use. The same could be said about his choice of concrete as a material for his sculptures.

Notes

Moore contributed a Portland stone relief to a building in this period as one of team of five sculptors, led by Eric Gill, chosen to produce reliefs of figures representing The Winds for the new Headquarters of the London Underground at St James Park Station in Westminster.

Anonymous review signed AHA, ‘The Yorkshire Artists’ 3rd Exhibition’, Yorkshire Observer, 25 January 1930.

George Whitfield, ‘The Curved Lady in Concrete. Remarkable Example of Sculpture’, Liverpool Echo, 14 June 1929.

Four of Moore’s concrete sculptures exist in more than one example: Duck 1927 (one concrete and one bronze example); Half-Figure 1929 (two concrete casts); Mother and Child 1932 (one concrete example and one painted plaster); Four-Piece Composition 1934 (nine bronze casts were made in 1962).

See Oliver Andrews, Living Materials: A Sculptor’s Handbook, Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1988, p.87.

Judith Collins is an author and former curator at Tate.

How to cite

Judith Collins, ‘Henry Moore and Concrete: Cast, Carved, Coloured and Reinforced’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www