Henry Moore OM, CH Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Image 1 of 16

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure

1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

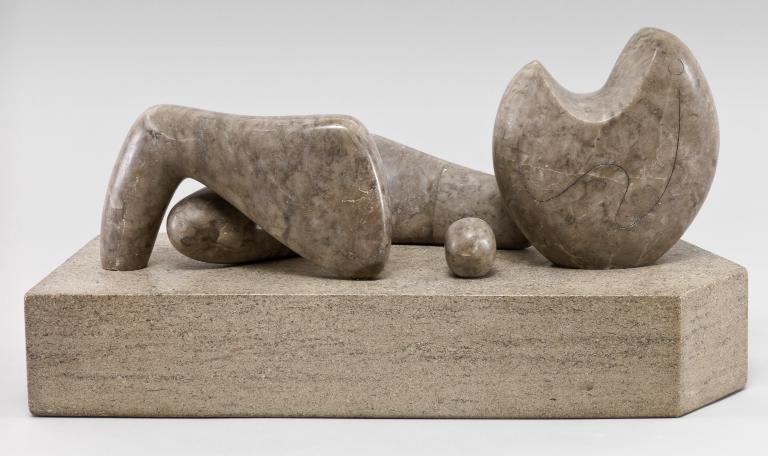

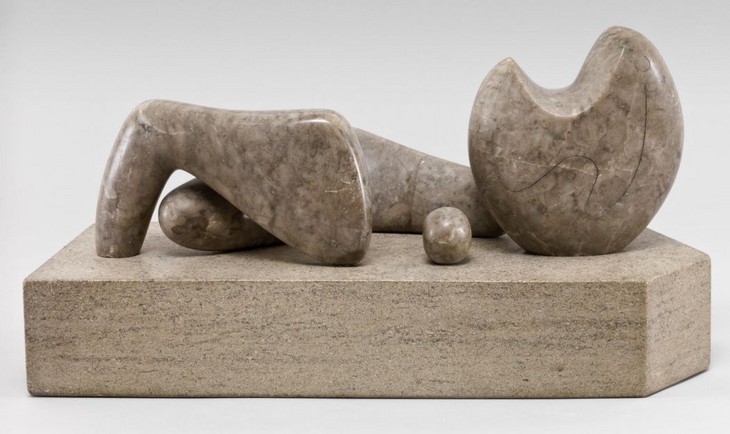

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure takes the form of a reclining figure split into four distinct parts. It is historically important as the first example of the way Henry Moore divided the human body into separate parts. The sculpture reflects the influence of Pablo Picasso and surrealism on Moore’s work of the 1930s.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure

1934

Cumberland alabaster on a Purbeck marble base

175 x 457 x 203 mm

Purchased from the Mayor Gallery (Grant-in-Aid) with assistance from the National Art Collections Fund, 1976

T02054

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure

1934

Cumberland alabaster on a Purbeck marble base

175 x 457 x 203 mm

Purchased from the Mayor Gallery (Grant-in-Aid) with assistance from the National Art Collections Fund, 1976

T02054

Ownership history

Acquired from the artist by Mrs Lois Culver Orswell through Buchholz Gallery, New York, 1946; by whom sold to Curt Valentin Gallery, New York, in 1952; bought from the estate of Curt Valentin by Martha Jackson, New York, 1955, and thence by decent to her son, David Anderson, by whom sold to the Mayor Gallery, London, in 1973; by whom sold to Sir Robert Adeane, 1973; bought from Sir Robert Adeane through the Mayor Gallery by Tate in 1976.

Exhibition history

1935

Fourteenth Exhibition of the 7 & 5 Society, Zwemmer Gallery, London, October 1935, no.7.

1935

Abstract Art: Sculpture, Painting, Reliefs, Everyman Cinema, London, November 1935.

1936

Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, Leicester Galleries, London, November 1936, no.19 (as ‘Composition (Cumberland alabaster)’).

1946–7

Henry Moore, Museum of Modern Art, New York, December 1946–March 1947; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, April–May 1947; San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, July–August 1947, no.29.

1955

Closing Exhibition: Sculpture, Drawings and Paintings, Curt Valentin Gallery, June 1955, no.141 (as ‘Four Piece Composition’).

1961

Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carvings, Marlborough Fine Art, London, June–July 1961, no.43.

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.34.

1973

A Loan Exhibition in Memory of Fred Hoyland Mayor, Mayor Gallery, November–December 1973, no.16.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, May–August 1977, no.21.

1978

Dada and Surrealism Reviewed, Hayward Gallery, London, January–March 1978, p.363, no.14.29.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal, Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.88.

1981

British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century. Part One: Image and Form 1901–50, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, September–November 1981, no.159.

1982–3

Henry Moore: Early Carvings 1920–1940, Leeds City Art Galleries, Leeds, November 1982–January 1983, no.31.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.20.

1996

Un Siècle de Sculpture Anglaise, Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris, June–September 1996, no number.

1997

Années 30 en Europe: le temps menaçant 1929–1939, Musee d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, February–May 1997.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986: ein Retrospektive zum 100 Geburtstag, Palais Harrach Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March–August 1998, no.5.

2001

Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, February–May 2001; Legion of Honor, San Francisco, June–September 2001; National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., October 2001–January 2002, no.26.

2009

Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson in the 1930s: A Nest of Gentle Artists, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich, January–April 2009; Graves Gallery, Sheffield, May–August 2009, no.15.

2010–11

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 2010–February 2011; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011, no.54.

2012

Picasso and Modern British Art, Tate Britain, London, February–July 2012; Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, August–November 2012, no number.

References

1935

Fourteenth Exhibition of the 7 & 5 Society, exhibition catalogue, Zwemmer Gallery, London 1935, reproduced no.7.

1935

Geoffrey Grigson, ‘Comment on England’, Axis, 1 January 1935, pp.8–10, reproduced p.9 (as ‘Carving’).

1935

S. John Woods, Abstract Art: Sculpture, Painting, Reliefs, exhibition catalogue, Everyman Cinema, London 1935, reproduced.

1944

Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944, reproduced pls.43a and 43b.

1955

George Wingfield Digby, Meaning and Symbol in Three Modern Artists: Henry Moore, Edvard Munch, Paul Nash, London 1955, reproduced fig.33.

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, London 1957, p.91, no.154.

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, reproduced fig.15.

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, p.46, reproduced pl.22 (incorrectly stated as belonging to Sir Herbert Read).

1961

Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carvings, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1961, pp.17–18.

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, reproduced pl.67, p.90.

1965

Myfanwy Piper, ‘Back in the Thirties’, Art and Literature, no.7, Winter 1965, pp.136–62, reproduced p.154.

1967

Charles Harrison, ‘Abstract Painting in Britain in the Early 1930s’, Studio International, April 1967, pp.180–91.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, reproduced p.77.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, New York 1968, reproduced pl.53, p.55.

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, pp.6, 93, reproduced pls.4, 86.

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, 1921–69, London 1970, reproduced fig.105.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973, reproduced p.84.

1973

A Loan Exhibition in Memory of Fred Hoyland Mayor, exhibition catalogue, Mayor Gallery, London 1973, reproduced pp.42–3.

1975

Robert Knott, ‘The Myth of the Androgyne’, Artforum, vol.14, no.3, November 1975, pp.38–45, reproduced p39.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et Dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977, reproduced pl.21.

1977

Alan Wilkinson, The Drawings of Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1977, reproduced p.89, fig.32.

1978

Dawn Ades (ed.), Dada and Surrealism Reviewed, exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.363.

1978

Anna Gruetzner Robins, ‘Henry Moore’, Unit 1, exhibition catalogue, Portsmouth City Museum and Art Gallery, Portsmouth 1978, p.8.

1979

[Richard Morphet], ‘Henry Moore: Four-Piece Composition 1934’, in The Tate Gallery 1976–8: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1979, pp.116–22.

1982

Henry Moore: Early Carvings 1920–1940, exhibition catalogue, Leeds City Art Galleries, Leeds 1982, reproduced p.72.

1982

Michael Newman, ‘British Sculpture: The Empirical Object’, Art in America, vol.70, no.4, April 1982, pp.119–25, reproduced p.122.

1988

Britannica: Trente Ans de Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Musée des Beaux-Arts André Malraux, Le Havre 1988, pp.7–21.

1988

Penelope Curtis, Modern British Sculpture from the Collection, display catalogue, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool 1988, reproduced p.44.

1990

Simon Wilson, Tate Gallery: An Illustrated Companion, London 1990, reproduced p.187.

1994

Charles Harrison, English Art and Modernism 1900–1939, 1981, revised edn, New Haven 1994, reproduced p.272, fig.143.

1995

Charles Harrison, ‘England’s Climate’, in Brian Allen (ed.), Towards a Modern Art World, New Haven 1995, pp.207–26.

1997

Richard Morphet, ‘Seeing the Many Sides of Moore’, Christian Science Monitor, April 1997, http://www.csmonitor.com/1997/0414/041497.home.home.1.html/(page)/2, accessed 11 September 2013.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986: ein Retrospektive zum 100 Geburtstag, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998, reproduced p.151.

1999

Michael Remy, Surrealism in Britain, Aldershot 1999, p.133, reproduced fig.54.

1999

Penelope Curtis, Sculpture 1900–1945: After Rodin, Oxford 1999, reproduced fig.99.

2000

Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art and the Post-Columbian World: Ancient American Sources of Modern Art, New York 2000, reproduced p.120.

2001

Steven A. Nash, ‘Moore and Surrealism Reconsidered’, in Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, pp.43–51, reproduced pp.46, 105.

2004

Emma Barker, ‘English Abstraction: Nicholson, Hepworth and Moore in the 1930s’, in Steve Edwards and Paul Wood (eds.), Art of the Avant-Gardes, London 2004, pp.273–304, reproduced p.291.

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007, reproduced p.37.

2010

Jennifer Mundy, ‘Comment on England’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, pp.22–37, reproduced p.22.

2012

Christopher Green, ‘Henry Moore and Picasso’, in James Beechy and Chris Stephens (eds.), Picasso and Modern British Art, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2012, pp.130–49, reproduced p.145.

Technique and condition

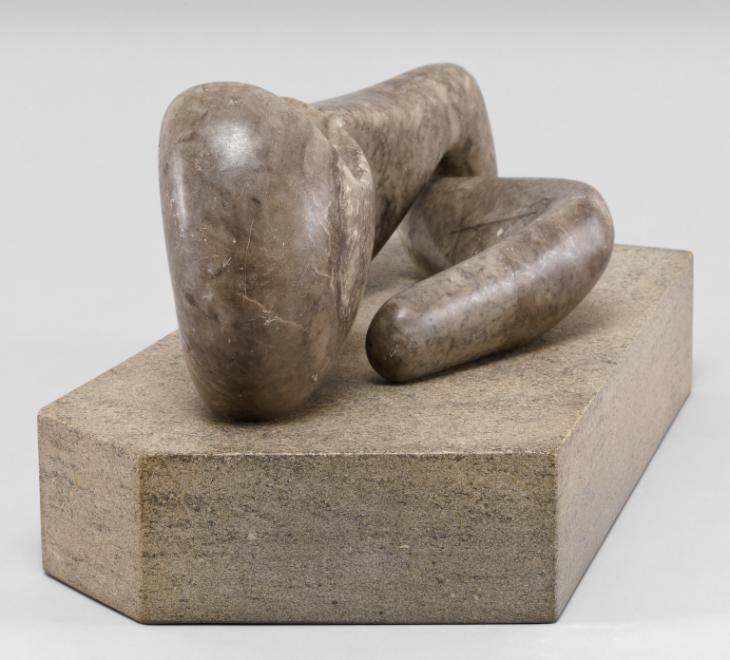

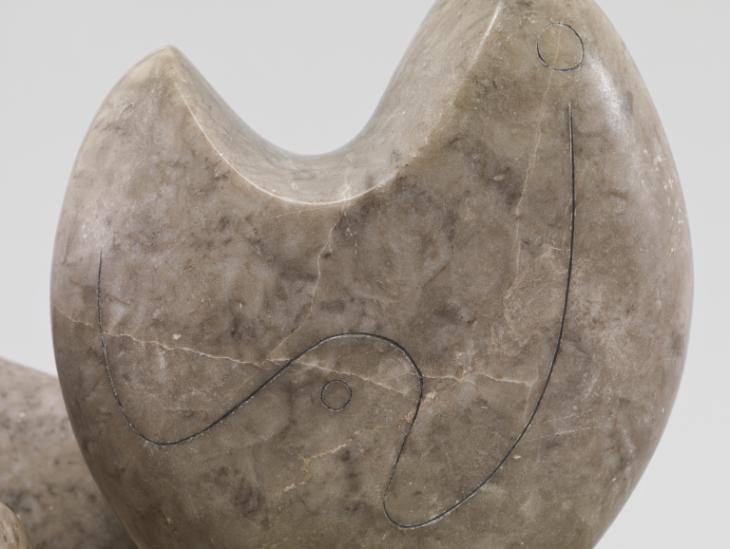

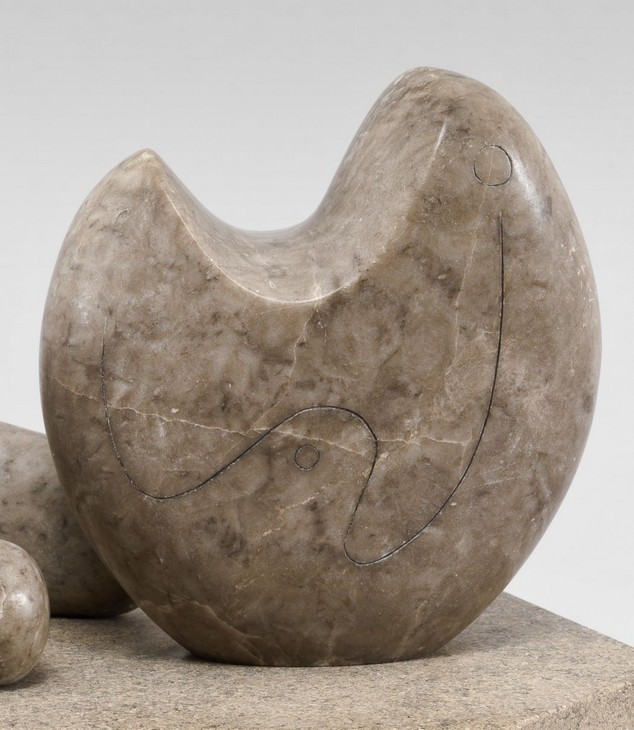

The sculpture comprises four polished forms that, when viewed together, represent an abstract reclining human figure. The individual elements are carved from Cumberland alabaster and are mounted on a deep Purbeck marble base in the form of an irregular pentagon. Two of the four forms have incised linear and circular decoration and close examination reveals that Moore carved these lines with a ‘v’ shaped tool leaving a deep narrow groove in the smooth alabaster surface. An unidentified dark material has then been rubbed into the lines to make them more visually prominent (fig.1).

Moore would have roughed out the forms from small blocks of alabaster using progressively smaller chisels. The shape would then have been refined using files before being sanded and polished to give a fine finish. The recumbent ‘leg piece’ has a fine joint at one end (fig.2). In 1979 Richard Morphet, then Deputy Keeper of the Modern Collection at the Tate Gallery, noted that this join was the result of a repair carried out after the sculpture was completed in 1934 but before it was acquired by Tate.1

Detail of repair on leg of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of repair on leg of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Underside of marble base of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Underside of marble base of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The individual pieces are all fixed via screws that pass through six holes drilled in the base from underneath (fig.3). Two screws are used to attach each of the two ‘legs’, one for the small sphere, and one larger screw to fix the upright ‘torso’. The present base is an exact replica of the 1934 original and was made by Moore in 1972. This replaced the base that previous owners of the work had fabricated to their own design. The original five-sided base was integral to the sculpture in that Moore had intended the arrangement of the four elements mounted upon it to dictate its form.

The sculpture is unsigned.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

Notes

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

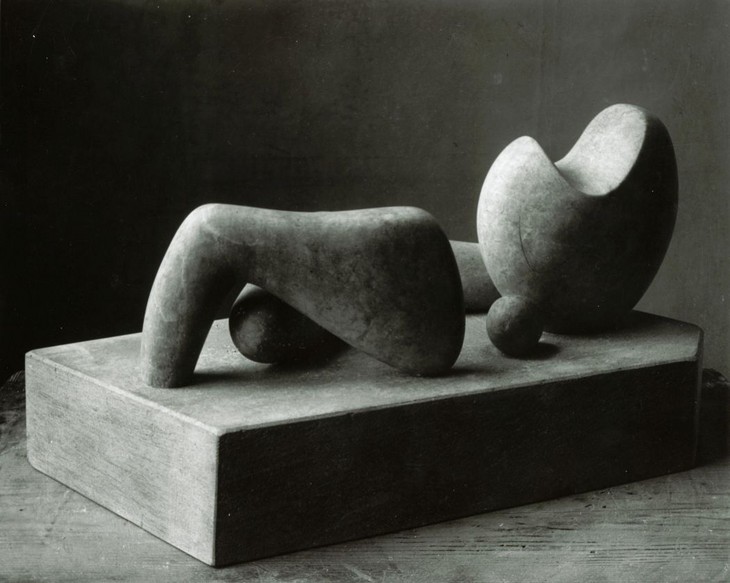

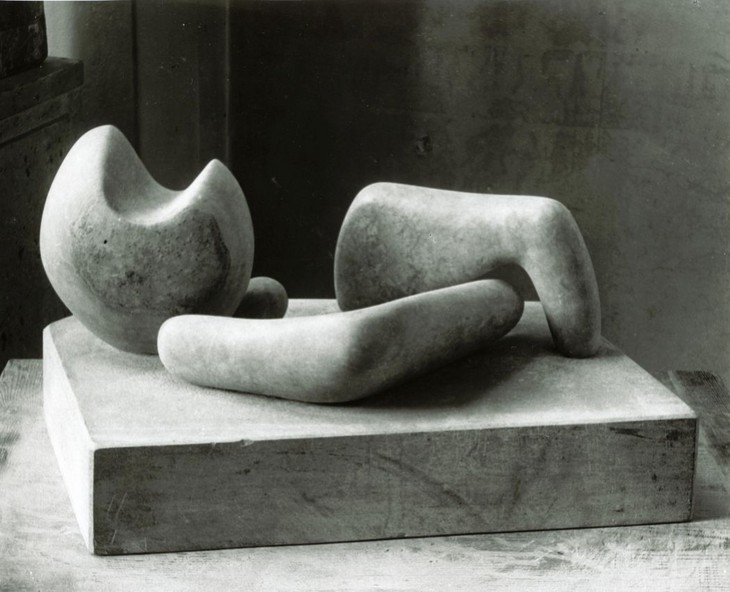

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure is a carving in Cumberland alabaster comprising four separate elements positioned on a Purbeck marble base. The individual elements of the sculpture do not accurately resemble human body parts, but when seen together, and in accordance with the work’s title, the four pieces may be understood as individual limbs. In 1968 Henry Moore described the sculpture as comprising ‘the head part, the leg part, the body, and the small round form, which is the umbilicus and which makes a connection’.1 Although they are positioned in a compact arrangement none of the four pieces of the sculpture touch each other.

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Cumberland alabaster on a Purbeck marble base

175 x 457 x 203 mm

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Detail of head and body of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Detail of head and body of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The front view of the sculpture is usually deemed to be that which positions the tallest wheel-shaped form on the right (fig.1). Three of the pieces are positioned on a single plane at the front of the base while the fourth is to the rear. The wheel-shaped form represents not only the head but also the top part of the body, including the arms; it has a large curved U-shaped declivity carved out of the upper section (fig.2). The flat front side has been incised with two small, but different sized circles and a single curved, meandering line. The larger of the two circles is positioned to the right of the declivity and just above the end of the incised line. The other circle is positioned between the central peak of the line. Seen in relation to the carved out space, the larger circle may be regarded as an eye so that the concave space becomes akin to an open mouth. The rear of this piece is slightly concave and does not have any incisions.

The small sphere or pebble is positioned between the larger wheel-shaped form on the right and the standing arch-shaped form to the left. The latter piece is reminiscent of a leg bent at the knee and is the most anatomically literal element of the sculpture. The space underneath the arch is triangular while the outer profile of the arch is loosely quadrilateral in shape. The arch balances on the base at two points: on the right, the stone (the top of the thigh or buttock) seems to be balancing on a curved point, while on the left the cylindrical calf has been cut horizontally to sit flush with the base.

Detail of incised circle and line on leg of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of incised circle and line on leg of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of repair on leg of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of repair on leg of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Behind these three pieces is a boomerang-shaped element that is positioned resting flat on the base. Although Moore identified it simply as a ‘body part’, the piece may be regarded as a leg, the end of which peeks through the arch of the other leg piece. A small shallow circular incision has been drilled into the inner calf area of this element, close to the knee bend. It is surrounded by an incised circle and a single straight line extends from the hole, crosses the circle and runs half way down the inner leg (fig.3). A repair join is visible mid-way along the thigh area of this fourth piece (fig.4).

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure is carved in Cumberland alabaster, a fine-grained variety of gypsum found in northern Lancashire and Cumbria.2 Alabaster is a soft stone and is often white or translucent. Moore had started using alabasters of various kinds in the late 1920s, but he came to prefer the type from Cumberland because of its greater density and because it does not have the translucency that is characteristic of alabaster in general. The type of Cumberland alabaster used by Moore in Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure is marble-like in its brown-grey colouring and veining.

Moore’s use of English stones was not unusual at this stage in the artist’s career. In 1978 Moore accounted for his use of English stones, stating:

in the early part of my career I made a point of using native materials because I thought that, being English, I should understand our stones. They were cheaper, and I could go round to a stonemason and buy random pieces. I tried to use English stones that hadn’t been used before for sculpture. I discovered many English stones, including Horton Stone, from visiting the Geological Museum in South Kensington, which was next door to my college.3

Henry Moore

Head and Ball 1934

Cumberland alabaster on Horton stone base

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Head and Ball 1934

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore created Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure at his London studio at Parkhill Road, Hampstead towards the end of 1934. The sculpture has a generally consistent, smooth, polished surface. Moore and his contemporaries, including Skeaping and Barbara Hepworth, used the method of direct carving to make their sculptures, meaning that they worked directly on the stone, using a range of chisels, rifflers and hammers, without the aid of drawn plans or maquettes (scale models made in clay or plaster). When carving directly into the stone or wood to create a unique artwork, the form or shape of the final sculpture evolved through the processes of its making, as the artist responded to the characteristics of the material. In 1934, the year this sculpture was made, Moore articulated his approach to carving in his statement for the publication Unit One:

Every material has its own individual qualities. It is only when the sculptor works direct, when there is an active relationship with his material, that the material can take its part in the shaping of an idea. Stone, for example, is hard and concentrated and should not be falsified to look like soft flesh – it should not be forced beyond its constructive build to a point of weakness. It should keep its hard tense stoniness.8

However, this did not mean that the forms found in Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure were determined by the original shapes of Moore’s rough lumps of alabaster. As Richard Morphet explained in 1979:

the alabaster in its pre-carved state did not at all resemble any of the four forms which Moore finally made. Even the smallest or pebble-like element was made by removing and refining a small piece from a larger lump of the alabaster. Moore simply cut all the parts of the alabaster to fit the idea; as it was a soft material, this was very easy to do.9

Instead, Moore believed that prioritising the inherent characteristics of the raw material would provide the sculpture with what he described as its own ‘vitality ... an intense life of its own, independent of the object it may represent’.10 Adhering to the methods of direct carving meant that the sculptor consciously respected the nature of the material and worked with it to bring out its particular ‘vitality’. As a consequence, uncluttered surfaces that emphasised the colour and veining of the stone were preferred so that ‘the physical reality of the material should declare itself’.11 By maintaining the ‘stoniness’ of the stone Moore sought to ensure that the sculpture existed not simply as a representation of its subject, but also as a physical object in its own right. However, following a conversation with Moore in 1978, Morphet explained that Moore ‘decided to stop using it [Cumberland alabaster] partly because so many peoples’ enthusiastic response to works he made in it was to the beauty of the material, to the exclusion of an understanding of the works’ essential – i.e. their sculptural – character’.12

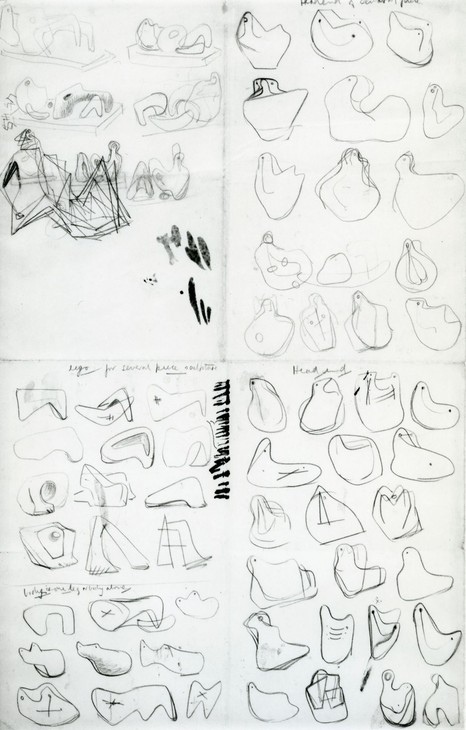

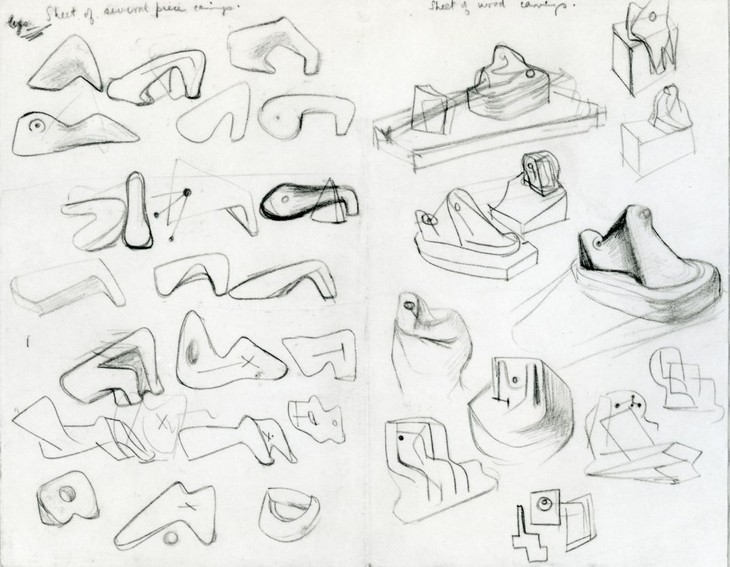

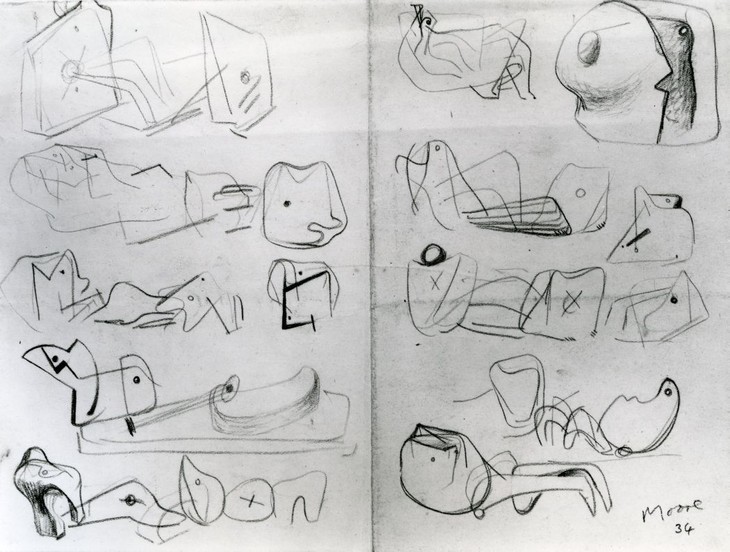

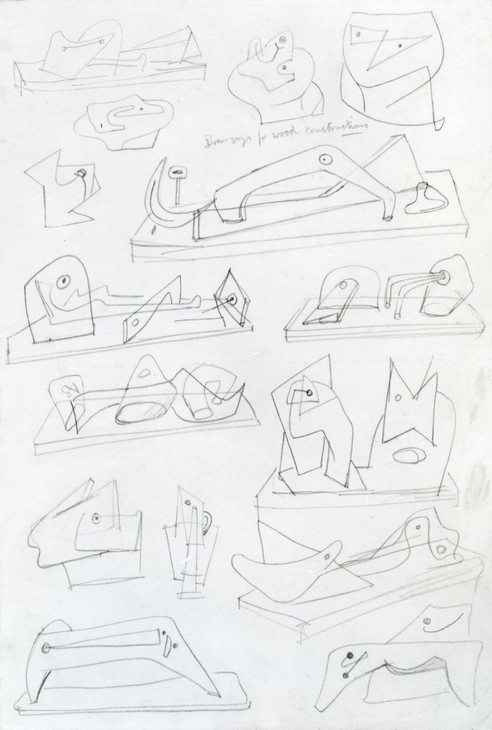

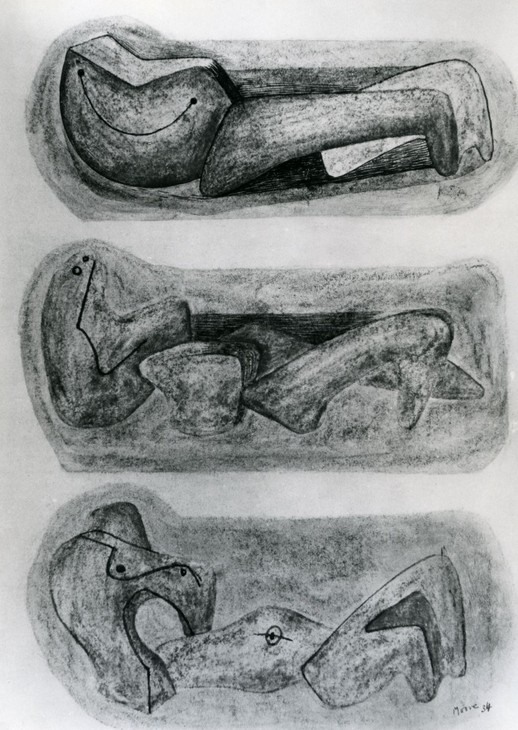

Although Moore’s method of direct carving meant that he did not work the stone according to a fixed, pre-existing plan, he did nonetheless use drawings as a way of testing out ideas prior to making sculptures. In 1934 Moore covered at least four sheets with shapes that can be related to Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure, and in 1937 he explained the relationship between his drawings and his sculptures:

My drawings are done mainly as a help towards making sculpture – as a means of generating ideas for sculpture, tapping oneself for the initial idea: and as a way of sorting out ideas and developing them ... Experience though has taught me that the difference there is between drawing and sculpture should not be forgotten. A sculptural idea which may be satisfactory as a drawing always needs some alteration when translated into sculpture.13

Henry Moore

Page of Several-Piece Compositions 1934

Graphite and crayon on paper

420 x 271 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Page of Several-Piece Compositions 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Studies for Several-Piece Compositions and Wood Carvings 1934

Crayon on paper

213 x 271 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Studies for Several-Piece Compositions and Wood Carvings 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Sheet of Four-Piece Compositions 1934

Graphite and charcoal on paper

200 x 267 mm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Sheet of Four-Piece Compositions 1934

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The idea for a multi-part figurative sculpture preoccupied Moore for some time, as can be seen in other drawings such as Studies for Several-Piece Compositions and Wood Carvings 1934 (fig.7) and Sheet of Four-Piece Compositions 1934 (fig.8). In the first of these drawings the left-hand side of the page is full of leg variations; the two in the top centre of the page most closely resemble the arched leg of the sculpture. Although in this section of the drawing Moore has not positioned the individual elements on a base, the inclusion of a sketch at the bottom of the page comprising a N-shaped arch and a sphere does point to how Moore was testing the position of individual forms in relation to one another. The second of these drawings has been identified by Wilkinson as containing two sketches that are closest to the Tate sculpture.15 The two sketches are positioned one above the other at the bottom right of the sheet, to the left of Moore’s signature. Wilkinson noted that in these two sketches all four pieces included in the final sculpture had been brought together, although he acknowledged that in the carving one of the arched leg forms is positioned on its side rather than upright as it is depicted in the drawing.16

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure is the earliest of Moore’s reclining figures held in the Tate collection. Moore had carved his first reclining figure around 1924, but the subject became more prominent in his art from 1929 and became his most frequently recurring subject. In 1968 Moore explained his use and re-use of the reclining figure, stating:

I want to be quite free of having to find a ‘reason’ for doing the Reclining Figures, and freer still of having to find a ‘meaning’ for them. The vital thing for an artist is to have a subject that allows [him] to try out all kinds of formal ideas – things that he doesn’t yet know about for certain but wants to experiment with, as Cézanne did in his ‘Bathers’ series. In my case the reclining figure provides chances of that sort. The subject-matter is given. It’s settled for you, and you know it and like it, so that within it, within the subject that you’ve done a dozen times before, you are free to invent a completely new form-idea.17

Henry Moore

Composition 1931

Blue Horton stone

483 x 270 x 245 mm

The Henry Moore Family Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Composition 1931

The Henry Moore Family Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

According to Morphet, although ‘the configurations formed by the incisions were not intended to represent parts of the body explicitly’, Moore nonetheless used incised lines in Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure ‘in order to reinforce the work’s essentially figurative character’, and to ensure that the sculpture did not simply exist as an arrangement of forms.22 However, Morphet also noted that ‘these motifs are not intended to be pinned down to hard and fast particular readings’ which may explain the ambiguity of the incised marks on the boomerang-shaped piece.23 It is significant that in his description of this incision as a ‘second umbilicus’, Moore also used the word ‘could’ implying that his suggested reading may not be the definitive one. Indeed, in 1968 Moore had stated that ‘sculpture should always at first sight have some obscurities, and further meanings. People should want to go on looking and thinking; it should never tell all about itself immediately’.24 This obscurity inherent in the sculpture may also explain how and why the tallest element of the sculpture can be seen as both the body and the head simultaneously. For although the larger circle incised in the ‘head’ element is ‘like an eye’, Moore also recognised that the element was ‘nearly a body itself’.25 Additionally, although the carved-out U-shape may be regarded as an open mouth, Moore also noted that the wheel-shaped piece was ‘hollowed like a horned head’.26 According to Morphet, Moore carved the U-shape into the wheel piece ‘in order to counter the excessive abstractness and simplicity of the element ... If he had left it as a complete round flattish ball’ as it was depicted in the sketch seen in Sheet of Four-Piece Compositions 1934, ‘it would, he felt, have seemed too isolated. [Moore stated] “It needed some life putting into it”’.27 Moore would return to this hollowed-out head motif throughout his career, notably in Reclining Figure 1951 (Tate T02270) and Moon Head 1964 (Tate T02297).

The other sculptures in Cumberland alabaster that Moore was working on in 1934 were also multi-part works. Moore explained in 1968 that at this time in the early 1930s ‘I began separating forms from each other in order to be able to relate space and form together’.28 By making sculptures that comprised several separate forms Moore was experimenting not only with the shape of individual pieces, but also their relationship and interaction with each other, both individually and as a whole. In addition to these relations, between and within the sculpture, the elements also existed in space, and were therefore capable of highlighting how objects responded to and interacted with the spaces around them. Discussing Head and Ball, Moore noted ‘a head and a smaller form – really two heads, a small head and a big head – but they are connected by space (that is the distance they are apart)’.29

This concern with space also explains Moore’s use of an irregularly shaped pentagonal base. Morphet noted:

He gave these works bases of an irregular design in order the more clearly to articulate those relationships in space (between a single sculpture’s discrete elements) with which he was so particularly concerned. In plan, a rectangular base is like a picture frame; it contains the work. Wishing to make the sense of space a determining element in each of these sculptures, Moore decided to reverse, to a degree, this sense of container and contained by allowing the positioning of the elements – their outspread across a surface – to determine the plan of the base. The relationship of the sculpture’s forms in space depends crucially on their relationship to the surface on which they rest. He thus wished to give this surface maximum reality in its own right. This wish not only contributed to his decision to give its outer limits a more particular sense of definition than a simple rectangle would have had, but also led to his making the base unusually thick, so as to raise the surface to view as a distinctive element in itself. [Moore observed:] ‘A thin base would have been silly.’ Although the base normally rests in turn on a pedestal or other support, it is intended to have, to a degree, itself the function of a pedestal. Moore describes the relationship between Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure and its base as being akin to that between a Seurat painting and the painted frame made for it by the artist (which while not itself the picture is a vital element in its presentation).30

Of the multi-part sculptures Moore made in 1934 Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure is unique in the way the human figure is dismembered. In 1955 George Wingfield Digby, then a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, suggested that rather than presenting a living human figure, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure was in fact ‘exceedingly evocative of a group of human bones and skull, the severed remnants of some human life’.31 However, for Wingfield Digby the evocation of bones was not to be regarded as macabre or melancholic. Instead, ‘the dismemberment theme refers principally to the idea of death as a necessary preliminary to rebirth’, and he cited T.S. Eliot’s poem Ash Wednesday (1927) as a contemporaneous meditation on the interconnectedness of death, rebirth and resurrection: ‘Under a juniper-tree the bones sang, scattered and shining’.32

The subject of dismemberment is also addressed in psychologist Erich Neumann’s 1959 publication The Archetypal World of Henry Moore. Neumann ultimately regarded Moore’s fragmentation of the body in Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure as a dehumanisation of the human figure. He suggested that:

the separate parts are the expression of an abstract principle that not only denies the seeming reality of the empirical world, not only reduces all accidentals to the barest essentials, but breaks down the ‘anatomy of reality’ into fragments, so that all that is left is the position of the parts and the memory of the complete body image.33

Neumann viewed Moore’s abstraction of the human body not as a simplification or paring down of forms to their elementary, or symbolic shapes as Wingfield Digby did, but rather as a deformation, in which the original subject on which the sculpture is based – the body – all but disappears. As such, Neumann implied that Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure was anomalous in Moore’s work, which he regarded as being based on human relations and sensibilities.

Henry Moore

Drawings for Wood Constructions 1934

Graphite on paper

275 x 188 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Drawings for Wood Constructions 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Stringed Relief 1937

Graphite on cream medium-wove paper

279 x 184 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Stringed Relief 1937

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Although Moore continued to experiment with multi-part sculptures into the later 1930s these works were principally non-figurative and he did not return to the theme of the fragmented body until the late 1950s and early 1960s with the development of his bronze two- and three-piece reclining figures (see, for example, Two-Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960, Tate T00395). Morphet suggested that one of the reasons why Moore did not carry on exploring the fragmented body was that ‘in doing so would in his view have run the risk of the viewer losing track of the fundamental subject of this and all his work, the human figure’.34 However, in the ideas developed in sketches in 1934, such as Drawings for Wood Constructions 1934 (fig.10), it is clear that Moore did continue to think about the relationship of individual sculpted elements between and within space. Through these drawings it is possible to draw a link between Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure and his stringed sculptures of the later 1930s, such as Stringed Relief 1937 (fig.11), in which the relations between form and space, and the interconnectedness of parts within a single sculpture are explored.

In his conversation with Morphet Moore asserted that the principal inspiration for his incised marks on Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure were Paleolithic bone engravings, which the artist probably saw in the British Museum.35 Moore noted that in the Paleolithic works the incised lines are dark in comparison to the off-white colouring of the bone and explained to Morphet that he:

did not want his own incised marks to look very new against the dark alabaster (which he knew would grow still darker through handling). In combination with his response to the Paleolithic engravings, this instinct led him to darken, once made, the marks he had incised ... Moore wanted them to be dark but not emphatically so. To achieve this he thinks his likely means were either pencil or the end of a burnt match (he smoked a lot then), rubbed into the line to produce a matt effect.36

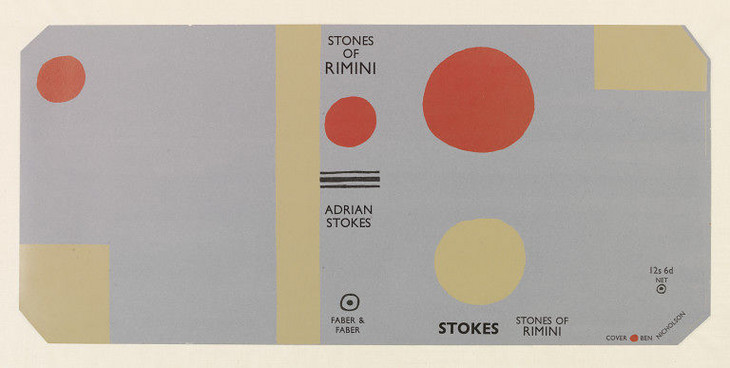

Ben Nicholson

Bookjacket for Adrian Stokes, The Stones of Rimini c.1935

Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig.12

Ben Nicholson

Bookjacket for Adrian Stokes, The Stones of Rimini c.1935

Victoria and Albert Museum

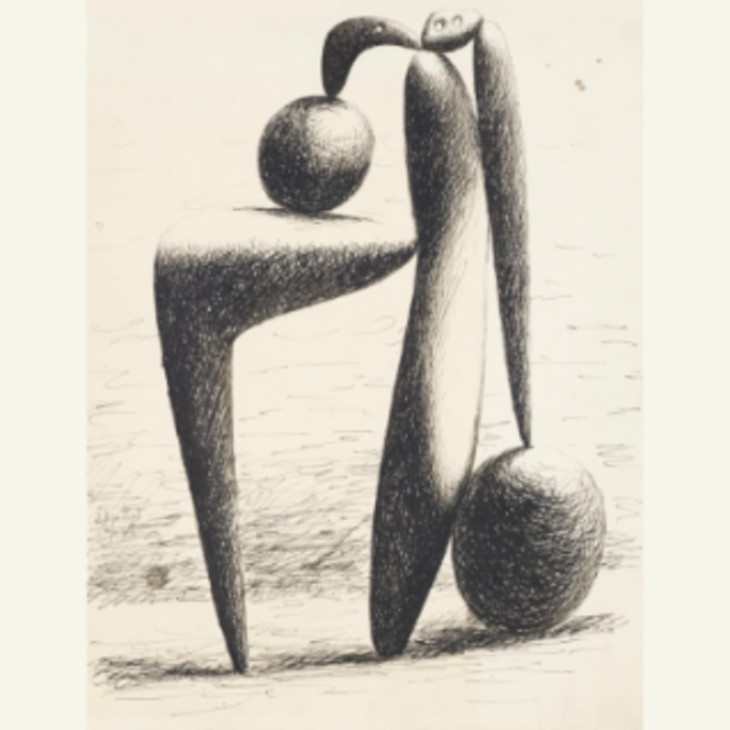

Pablo Picasso

Project for a Monument 1928

Graphite on paper

Private collection

© Succession Picasso/DACS

Fig.13

Pablo Picasso

Project for a Monument 1928

Private collection

© Succession Picasso/DACS

Henry Moore

Studies for Sculpture 1934

Chalk, watercolour, pen and ink on paper

559 x 381 mm

Collection of Kenneth Clark

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Studies for Sculpture 1934

Collection of Kenneth Clark

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore had been aware of Picasso’s work since his student days at Leeds School of Art, and in 1973 reflected that ‘really all my practicing life was as a student, and as a sculptor I have been very conscious of Picasso because he dominated sculpture and painting – even sculpture as well as painting – since Cubism’.40 Moore first visited Paris, where Picasso lived and worked, in 1922 and made regular trips to the city until the mid-1930s in order to study contemporary artistic trends and developments. These visits were supplemented by his study of photographic reproductions included in French art periodicals including Cahiers d’Art (from 1926) and Documents (1929–30). Both these journals championed the work of Picasso as a major force in contemporary art and in 1930 Moore bought the third issue of Documents, a special edition dedicated to Picasso’s work.41 In this publication Moore saw reproductions of Picasso’s drawings and paintings made in Cannes in c.1927–9 of monumental nude women standing on a beach. In works such as Project for a Monument 1928 (fig.13) the human body is presented as a sequence of precariously balanced vertical and boomerang-shaped beams positioned alongside two ovoids and capped with a smaller boomerang shape and a third, smaller ovoid, pierced with two holes, which may represent eyes. The art historian Christopher Green has argued that Moore was able to respond to Picasso’s drawings and paintings because both artists rooted their art ‘in their knowledge of the human body, however far they moved from straight representation’.42 Moore’s 1934 drawing Studies for Sculpture (fig.14), which includes a drawing directly related to Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure, does bear a striking resemblance to Picasso’s multi-part bathers of 1928–9, although Moore chose to present reclining, rather than standing figures.43

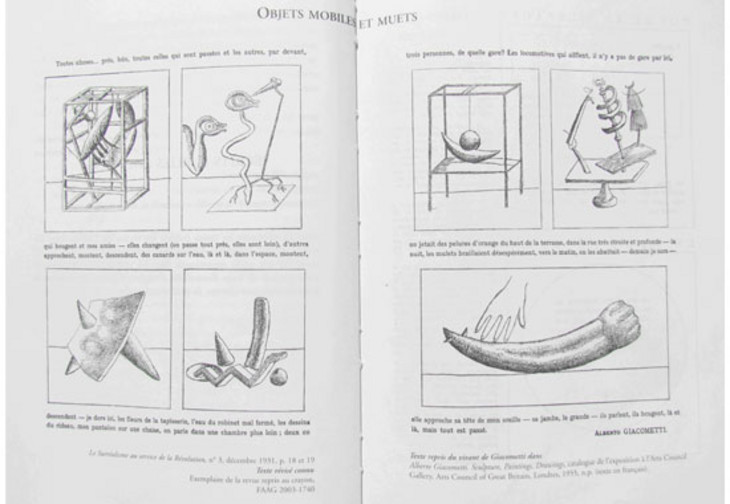

Alberto Giacometti's Objets mobiles et muets in Le Surréalisme au Service de la Révolution, no.3, December 1931, pp.18–19

Fig.15

Alberto Giacometti's Objets mobiles et muets in Le Surréalisme au Service de la Révolution, no.3, December 1931, pp.18–19

Moore’s links to and interest in contemporary art from Europe has lead many art historians to regard Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure as a surrealist sculpture, and it has been included in a number of survey exhibitions devoted to surrealist art. This interpretation of the sculpture is not without credence; in April 1933, the year before he made this sculpture, Moore contributed four sculptures to the first surrealist exhibition in London, Exhibition of Recent Paintings by English, French and German Artists, at the Mayor Gallery, which also exhibited works by surrealist artists including Miró, Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí. And in 1936 Moore was on the selection committee for the International Surrealist Exhibition held at the New Burlington Galleries in London. Given that Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure was made in between these two exhibitions, it would seem reasonable to assert that the sculpture grew out of Moore’s engagement with surrealist ideas and practices. In 1999 art historian Michel Remy argued in his book Surrealism in Britain that Moore’s opening out of the human body in Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure is what makes the work surreal: ‘the viewer is obliged to change his place, height, and angle of vision to see and construct the piece. There is no finality to cling to; the viewer is plunged into an infinite movement of inclusion and exclusion, as the eye goes round’.46 For Remy, it is this lack of finality and consequential contingency that is surreal. However, when asked by Morphet whether Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure could be regarded as a surrealist work:

Moore replied by recalling that in 1934, when the break-up of Unit One was reflecting the increasing conflict being felt in Britain between the two divergent directions of modern art, he felt that there was no reason why an artist should have to choose between a rational and an irrational approach, since it was of the nature of art that both were always present in the creation of work ... this four-piece carving involved a high degree of conscious control, including a concern, among others, with formal properties; but in a work [Moore said] ‘there must be gaps that you can’t explain, there must always be a jump’.47

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934, photograph taken c.1934–5

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934, photograph taken c.1934–5

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934, photograph taken c.1934–5

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.17

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934, photograph taken c.1934–5

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934, Photograph taken c.1934–5

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.18

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934, Photograph taken c.1934–5

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934, photograph taken c.1934–5

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.19

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934, photograph taken c.1934–5

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

At some point between completing the sculpture towards the end of 1934 and October 1935 Moore took a series of photographs showing the sculpture from four different angles (figs.16–19). The art historian Elizabeth Brown has noted that Moore would have been alert to the importance of good photographic reproductions of sculptures from reading magazines such as Cahiers d’Art.48 While most of Moore’s photographs from the early 1930s were documentary and archival in nature, some, such as these images of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure, presented sculptures from different angles with dramatic, raking light. Brown suggested that in this series of photographs Moore was emphasising his belief, conveyed originally in his statement for Unit One, that ‘Complete sculptural expression is form in its full spatial reality ... Sculpture fully in the round has no two points alike’.49 The four angles chosen to represent the sculpture demonstrate how Moore engaged with and harnessed the spatial complexities of his sculptural work in his photographs. Brown noted that since Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure has multiple constituent parts and does not have a single, fixed focal point, ‘Moore’s photographic series contributes substantially to the viewer’s understanding of his concept. Each photograph essentially presents a wholly new and different composition. Each juxtaposes familiar details or passages alongside uncanny ones’.50 In light of Brown’s analysis, it is significant that each of Moore’s four photographs have been variously reproduced in his monographs and catalogues, and may well have influenced the decision to devote the last four pages of the catalogue for Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins – an exhibition held at the Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, in 1977 – to a presentation of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure by the progressive enlargement of a single photograph, culminating in a detail of the pebble element on the catalogue’s back cover.

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure was first exhibited in the Fourteenth Exhibition of the 7 & 5 Society, held at the Zwemmer Gallery, London, in October 1935. According to the art historian Charles Harrison this exhibition was ‘considered at the time to be the first all-abstract exhibition in England’ and identified the aspirations of Moore, Nicholson, Hepworth and others within the context of European modernism.51 Despite the art historical importance of the exhibition, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure failed to find a buyer, and it was included in Moore’s exhibition at the Leicester Galleries the following year. The work remained in Moore’s possession and was later included in his retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, which opened in December 1946, before touring to the Art Institute of Chicago and the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1947.

It was while the sculpture was on tour in the United States that it was purchased by Lois Culver Orswell (1904–1998), through the Buchholz Gallery, New York, in December 1946 for the sum of $1,300. Culver Orswell was only able to receive the sculpture after the exhibition tour had finished in Decmber 1947. Known also as Lois Orswell and Lois Orswell Dailey, Culver Orswell was an important patron of modern art in the United States who already owned work by Moore prior to her acquisition of Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure. She is perhaps best known for her focused collection of modern sculpture and in particular her patronage of the American sculptor David Smith.52

At the time Culver Orswell aquired the sculpture, the Buchholz Gallery was run by the German art dealer Curt Valentin, who in 1951 renamed it the Curt Valentin Gallery. In 1952 Culver Orswell returned Moore’s sculpture to Valentin as part payment for the acquisition of a sculpture by Jacques Lipchitz called Trentina. Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure remained on the gallery’s inventory and was included in the gallery’s closing exhibition in 1955, following Valentin’s death in August 1954. Nothing is known of the sculpture’s history while it was in Valentin’s possession between 1952 and 1955; according to Ralph F. Colin, who looked after Valentin’s estate, ‘Curt Valentin was notably not a good record keeper’.53

Despite his apparently poor record keeping, Valentin was one of New York’s most respected art dealers in the 1940s and 1950s. Moore first exhibited with Valentin at the Buchholz Gallery in May 1943 and Valentin became Moore’s sole agent in the United States. Although Moore did not get to know Valentin until his vistit to New York in 1946 for the opening of his show at MoMA, during the trip they became close friends. From 1948 until his death Valentin spent every Christmas with the Moores at their home, Hoglands, in Hertforshire. In September 1954, shortly after Valentin’s death, Moore wrote, ‘I begin to realise all the more now that he is dead how much he meant to me. How much, all the time, one unconsciously counted on his steadfast support, on him being there, tirelessly working for the cause of the painters and sculptors he believed in’.54

Following Curt Valentin’s death, Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure was bought from his estate by the New York based art dealer Martha Jackson in the spring of 1955, and it entered her possession in June that year. According to her son, David Anderson:

from the time of it’s [sic] arrival in 1955 until Martha’s death in 1969 the sculpture was more or less permanently located on the coffee table in her apartment and was always deemed part of her collection. However, the [Martha Jackson] Gallery actually owned the sculpture from 1960, as Mrs Jackson then in fact contributed her collection of works to the gallery corporation as a part of it’s [sic] initial capitalization; I ‘acquired’ the sculpture through my purchase of the Gallery shares from the estate in December of 1969; although the sculpture then came to live with my wife and I (except when on exhibition, etc) in our home.55

Sometime after the sculpture came into the official ownership of the Martha Jackson Gallery in 1960 the original stone base was replaced with a polished black marble one of different dimensions, possibly because the original had become chipped or dirty. However, in 1972 Anderson discovered some old photographs of the sculpture – possibly those taken by Moore – and contacted Moore to enquire whether a replica of the original base could be made. Moore agreed and the sculpture was shipped to England. In a letter to Anderson dated 11 July 1973, Moore wrote:

You will be pleased to hear that I have been able to get the FOUR PIECE COMPOSITION off the [black] marble base safely and I have remade in shape, as near as I can, my original base – and in a stone as close to it as I have been able to get. And I think it looks infinitely better. Over the years a few little damages seem to have occurred to the sculpture itself, (alabaster is very delicate), but in some cases I have tried to hide them. Anyhow, it is now ready and we can send it to you.56

The sculpture remained in the possession of Anderson until September 1973, when ‘Mr Mayor chanced to see the sculpture at the gallery ... just as it had returned from Mr Moore’s; with the result that he made me an offer I felt I could not refuse, though I had no intention of disposing of the sculpture’.57

James Mayor, who aquired Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure from Anderson, was director of the Mayor Gallery, London. Founded by Freddie Mayor in 1925, the gallery had been among the first to exhibit international artists such as Max Ernst, Paul Klee, and André Masson. In 1933 the art critic Geoffrey Grigson observed that ‘as far as it can, the Mayor Gallery is doing the job, which should be carried out by the Tate, of educating us here in the recent logical developments of European and English art’.58 Grigson was writing in response to the gallery’s exhibition Art Now, selected by gallery co-director Douglas Cooper and held to coincide with the publication of Herbert Read’s book of the same title, which discussed works by Moore, Picasso and Francis Bacon. The gallery also became the headquarters of the group Unit One, founded by Paul Nash, whose members included Moore, Nicholson, Edward Wadsworth, Edward Burra and others. A few years prior to Freddie Mayor’s death in June 1973 his son James had succeeeded him at the gallery,59 and the sculpture was included in the exhibition A Loan Exhibition in Memory of Fred Hoyland Mayor, at the Mayor Gallery in November–December 1973.

In late 1973 the Mayor Gallery priced Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure at $100,000 (£46,000) and it was duly sold to a private collector, Sir Robert Adeane. In a memo to the Tate’s director, Norman Reid, dated 1976, Morphet noted that in 1973 the Mayor Gallery had apparently ‘dismissed the idea of approaching us [Tate; to purchase the sculpture] in the mistaken belief that we were guaranteed a thorough Moore representation by his impending gift’, which had been announced in the press in February 1967.60 When, in 1975, Adeane decided to sell the sculpture, he approached the Mayor Gallery to arrange the sale. Although another buyer had been identified, both Adeane, who was a member of the Friends of the Tate Gallery, and the Mayor Gallery agreed to give Tate preferential treatment. After some negotiations, financial assistance was secured from the National Art Collections Fund, and the sculpture entered the Tate collection in the latter half of 1976.

Alice Correia

January 2013

Notes

Cumberland was a county in north-west England from the twelfth century until 1974, when county boundaries were redrawn and it was absorbed into the neighbouring Lancashire and Cumbria.

See http://collection.britishcouncil.org/collection/artist/5/18427/object/44140/0 , accessed 16 January 2013.

See Henry Moore, Figure Carving 1935 (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.), http://www.hirshhorn.si.edu/search-results/?edan_search_value=Henry%20Moore#detail=http%3A//www.hirshhorn.si.edu/search-results/search-result-details/%3Fedan_search_value%3Dhmsg_66.3606 , accessed 16 January 2013.

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.191.

Henry Moore, ‘A Sculptor Speaks’, Listener, 19 August 1937, pp.338–40, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.196–7.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.88.

Steven A. Nash, ‘Moore and Surrealism Reconsidered’, in Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, pp.43–51, note 17, p.51.

George Wingfield Digby, Meaning and Symbol in Three Modern Artists: Henry Moore,Edvard Munch, Paul Nash, London 1955, p.77.

Moore did not specify where he saw the engraved Paleolithic bones. However, it is known that he studied the collections of the British Museum intently throughout the 1920s.

Russell 1973, p.82. David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.63.

For a discussion of Picasso’s influence on Nicholson see Christopher Green, ‘Ben Nicholson and Picassso’, in James Beechy and Chris Stephens (eds.), Picasso and Modern British Art, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2012, pp.92–103.

Henry Moore, ‘Interview with Elizabeth Blunt’, Kaleidoscope, BBC Radio 4, 9 April 1973, transcript reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.167. For further discussion on the debt Moore owed to Picasso see Herbert Read, Modern Sculpture, London 1964, pp.168–73, and Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, pp.47–52.

Lichtenstern 2008, p.49. For a facsimile of Documents, vol.2, no.3, 1930, see http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k32951f.image , accessed 30 July 2012.

Ann Garrould has noted that ‘Moore originally dated the drawing 35, and then changed the “5” to a “4”’. Whether Moore did this at the time he made the drawing or sometime after is unknown. See Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Complete Drawings 1930–39, London 1998, p.117.

Christa Lichtenstern, ‘Henry Moore and Surrealism’, Burlington Magazine, vol.123, no. 944, November 1981, p.645.

See [Morphet] 1979, p.121. For an image of Giacometti’s sculpture see http://www.moma.org/collection/object.php?object_id=81796 , accessed 11 September 2013.

See Elizabeth Brown, ‘Moore Looking: Photography and the Presentation of Sculpture’, in Kosinski 2001, pp.287–95.

Ralph F. Colin, letter to Richard Morphet, 7 February 1979, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23946.

David Anderson, letter to Richard Morphet, 1 May 1978, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23946.

David Anderson, letter to Richard Morphet, 1 May 1978, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23946.

Related essays

- Henry Moore’s American Patrons and Public Commissions Pauline Rose

- Henry Moore and Direct Carving: Technique, Concept, Context Sarah Victoria Turner

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Life Forms: Henry Moore, Morphology and Biologism in the Interwar Years Edward Juler

- Erich Neumann on Henry Moore: Public Sculpture and the Collective Unconscious Tim Martin

- Henry Moore and Stone: Methods and Materials Sebastiano Barassi and James Copper

Related catalogue entries

Related material

Related reviews and articles

- Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’ Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, London 1934, pp.29–30.

- Henry Moore, ‘On Carving’ New English Weekly, 5 May 1932, pp.65–6.

- Henry Moore, ‘The Sculptor Speaks’ Listener, 18 August 1937, pp.338–40.

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www