Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze

Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Moore became known first as a carver of stone and wood but after the Second World War he increasingly used bronze. This essay explores his approach to casting bronze and the various ways in which the qualities of metal and the processes of fabrication influenced his works.

Henry Moore first came to prominence as a carver of stone and yet he became famous internationally for his large bronzes, undertaken in the years following the Second World War. Bronze – a material associated with traditional, academic sculpture and based on a creation of a model that needed to be copied and cast – was not originally his preferred material. It would be a mistake, however, to see his choice of the medium as simply a late-career desire for greater scale and the provision of more works to meet increased client demand through the creation of editions. Bronze allowed Moore new freedoms in his conception of particular sculptures, and changed his techniques in ways that significantly influenced his later production.

Henry Moore

Bird 1927

Bronze

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Bird 1927

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Head of a Woman 1926

Concrete

The Hepworth Wakefield

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Norman Taylor

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Head of a Woman 1926

The Hepworth Wakefield

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Norman Taylor

In the 1920s and early 1930s Moore was committed to carving as a means of working directly with his materials. For him and others, direct carving offered a new aesthetic that stood in sharp contrast to the smooth finishes and naturalistic representations of traditional academic sculpture. However, his break with traditional methods was not complete. In response perhaps to client requests he produced a bronze horse in an edition of three in 1923, a reclining woman in 1926, and a bird in polished bronze in 1927 (fig.1), although he chose not to include photographs of any of these early works in his 1944 catalogue raisonné for reasons that are unknown. To try to learn casting techniques, he also made a number of concrete casts from the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s (see fig.2).1 Although such works evidence his early interest in working with a range of materials, he focused mainly on stone and wood in his early years, and was not to take up working in bronze until the late 1930s.

This shift in practice was at least, in part, he later argued, a product of greater experience. ‘When you are young you cotton on to an idea that helps you’, he later commented. ‘I’m glad I did all that carving but I know now that there has been modelled sculpture which is just as good.’2 But the change, of course, had profound practical and financial implications. As a process, carving is simple, and work can be produced without the costs and delays of involving founders. It leads to a single work, however, while casting permits the creation of editions that are produced by skilled craftsmen within a foundry, a process that does not necessarily require the artist’s direct involvement. This second path offered Moore significant advantages in allowing him a more consistent income so that he could continue in his chosen career: in the post-war years it was a form of production that both met, and arguably fuelled, the rising demand for his work, especially abroad, and brought him great wealth.3 Bronze was also a robust material and tended to age gracefully, an important consideration for an artist who wanted to leave his mark on the world. In an interview published in 1973, he commented, ‘You don’t have to be bothered about the problems of how it will stand up, how it will weather, how it will do from a purely practical point of view. This is the beauty of bronze.’4 (Note that the scale of Moore’s ambition was striking. The sculptor Anthony Caro, who worked as an assistant to Moore in the 1950s, said of him in 1988: ‘For Moore, being a modern sculptor was not a parochial thing: not eccentric, not small. The measure of his ambition was world-wide. He was prepared to put himself alongside the mainstream European masters; Miró, Ernst, Giacometti. He considered them his peers. No English sculptor before him had done this.’)5

Early bronze and lead casts

When he made his first bronzes, Moore was inexperienced and for the most part his early bronzes were made at professional foundries. He had had no formal training in bronze casting as this was something rarely offered in fine art schools at the time. There was then a social divide between the creator and the fabricator, and Moore was unusual in being willing to try his hand at all aspects of the processes of making sculptures. (Training in bronze casting was available, for example, at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, which described itself as being concerned solely with the ‘training of art and craft workers’ in the belief that ‘the fundamental aim and method of the education is production’.)6

Perhaps better to understand the processes of metal casting, he experimented with making lead casts in his kitchen in Parkhill Road, Hampstead, between 1929 and 1931. Lead was cheap and could be obtained relatively easily. Importantly, too, it had a low melting point, and Moore was able to work with the material using a saucepan on a primus stove. Unfortunately, little is known about these early lead works. In 1935 Moore managed to buy a bungalow called Burford Cottage with five acres of land near Kingston in Kent, and produced nearly twenty small lead works between 1938 and 1939, with the help of his first assistant, Bernard Meadows, whom he had taken on in 1936 while the latter was still a student.

There is little documentation surrounding these casting sessions aside from later interviews with Meadows and a few surviving photographs.7 However, it seems that Moore used the lost wax casting process, a technique dating back well over five thousand years and requiring simple equipment. In this process the model is made from wax and is surrounded with a refractory, or heat resistant, material that does not change its dimensions when exposed to high temperatures. In lost wax casting this material is usually called investment and is made up from plaster mixed with various additives, such as sand or ground ceramic. The wax model needs to have wax rods which, when melted away, will become channels through which molten metal can be poured into the mould and excess metal and gases can escape. Deciding on the optimum position for these rods is part of the founder’s craft and would have been something that Moore and Meadows would have learned during their casting sessions, probably through a combination of reading published texts and some trial and error. With a surrounding jacket of investment, the sculpture is heated and the wax melted out to leave a cavity in the shape of the original sculpture (hence the name, lost wax casting or ‘cire perdue’). At Burford Cottage Meadows constructed a firebrick kiln to burn the wax out from the moulds and also a small furnace in which lead could be melted using a crucible. The lead they used for casting was obtained from bits of lead pipe, old armatures that Moore salvaged from Chelsea School of Art and, despite Meadows protests, one of the artist’s earlier lead sculptures, Seated Figure 1930. Meadows later recalled how he and Moore would work all day and into the night to make a lead sculpture, melting the lead and once the cast had cooled, working of the surface with various files and finally sharkskin to give the resulting sculptures – each one unique – a smooth sheen.

Moore showed fourteen of his cast sculptures at an exhibition at the Leicester Galleries, London, in 1940. Reflecting in 1960 on this experience, he commented that the knowledge he had gained in casting lead sculptures himself had allowed him to conceive of sculptures that were thinner in shape, knowing that the structural properties of the metal would support these more open forms:

working direct in wax has many possibilities, since wax has a toughness about it that will allow you to do very thin forms ... you couldn't make ... in clay, nor in plaster, without awful trouble ... By working direct in wax, one was able to make shapes and forms much thinner and more open then ever you could have done direct in plaster. Doing my own metal casting led me to doing those.8

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Reclining Figure 1939, cast 1959

Bronze on wooden base

object: 137 x 254 x 86 mm

Tate T00387

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore OM, CH

Reclining Figure 1939, cast 1959

Tate T00387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Works such as Reclining Figure 1939 (fig.3) include fine rod-like shapes that would indeed have been difficult to achieve in wood or stone; although they echo the use of string in earlier sculptures, their forms appear to relate directly to the lost wax casting processes by which they were made. This period of making casts, however, was soon to be interrupted by the Second World War and a concomitant shortage of metal. Invited to be a war artist, Moore shifted his practice to focus on drawings, but as the war drew to a close he began to make a large number of small, and thus easily portable, terracotta sculptures, typically centred around themes of mother and child or family. Clay was a material that was freely available, and perhaps the experience of war had transformed Moore’s sense of what was an appropriate subject matter.

Post-war bronzes

Moore’s first large scale commission after the war was for a sculpture in Barclay School in Stevenage. During the war he had made drawings on the theme of grouped figures and portable terracotta maquettes, and from these chose an idea to develop. Meadows would have assisted Moore in making a full scale plaster model for the commission from a maquette. For a work of this size the plaster would have needed an internal armature on which successive layers of wet plaster would have been laid and then shaped through filing and sanding as it dried. The over life-size family group would then have been cut into a number of parts so that they could be transported to a foundry (a work of this size required the skills of a commercial founder) and to allow the different parts to be cast successfully. The cost of casting such a large and complex group was high (Meadows later suggested the sum was around £500).9

Henry Moore (centre) with the unfinished male figure of Family Group 1948–9 in the Fiorini and Carney Foundry, London c.1949–50

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore (centre) with the unfinished male figure of Family Group 1948–9 in the Fiorini and Carney Foundry, London c.1949–50

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

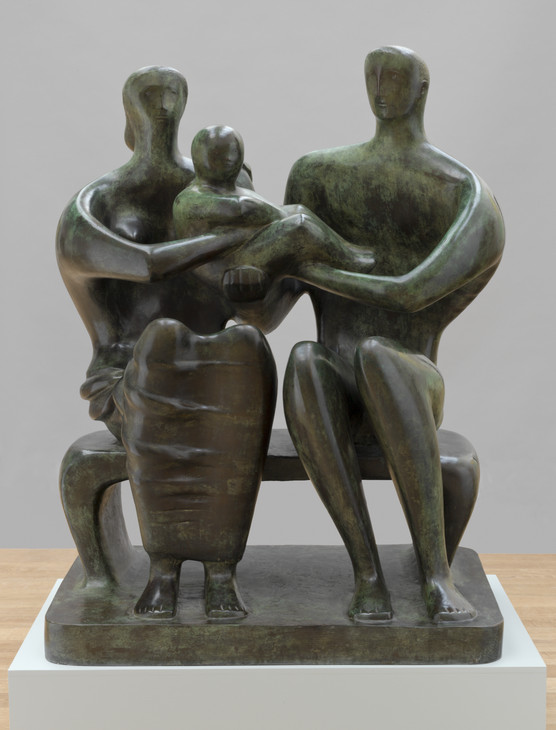

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Bronze

object: 1540 x 1180 x 700 mm, 475 kg

Tate N06004

Purchased 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore OM, CH

Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of roman join on Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of roman join on Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Exploiting the reproducibility of the medium, Moore agreed to sell the cast to the Barclay School at cost price on the proviso that he could use the plaster models again to make additional casts. He did not offer the task of making further casts to Fiorini and Carney – in a letter to the Museum of Modern Art in 1951 he recalled that the foundry had struggled with the sheer scale of the piece – and instead commissioned the Fonderie Rudier, one of the leading foundries in Paris, to make a further three casts in 1950–1. These were sold to the Museum of Modern Art, the wealthy patron and governor of New York Nelson D. Rockefeller, and the Tate Gallery. Examination of Tate’s cast reveals that it was made in at least ten parts, using the sand casting technique. The parts were connected using roman joints, an ancient technique that involves slotting the pieces together using an inner sleeve that is secured by large bronze pins. The heads of these pins are then filed down and hammered to match the surrounding surface. In Tate’s work a faint line from the join and a circle from the pin can be seen on the male figure’s left arm (figs.5 and 6).

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 installed on the South Bank during the Festival of Britain 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 installed on the South Bank during the Festival of Britain 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

At one time I became very interested in doing my own bronze casting. I had an assistant then who was ambitious to be a bronze caster rather than a sculptor. So I built a little foundry at the bottom of the garden. And I am very glad I did because I learnt so much about the characteristics of bronze which has been helpful to me ever since.12

Photograph showing, from left to right, Moore's assistants Alan Ingham, Aldo Calò (a visiting Italian sculptor), Anthony Caro and Oliffe Richmond by the 'backyard foundry' in the garden of Hoglands 1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Photograph showing, from left to right, Moore's assistants Alan Ingham, Aldo Calò (a visiting Italian sculptor), Anthony Caro and Oliffe Richmond by the 'backyard foundry' in the garden of Hoglands 1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Open Work Head No.2 1950

The Hepworth, Wakefield

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights reserved

Photo: Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Open Work Head No.2 1950

The Hepworth, Wakefield

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights reserved

Photo: Reserved

Henry Moore

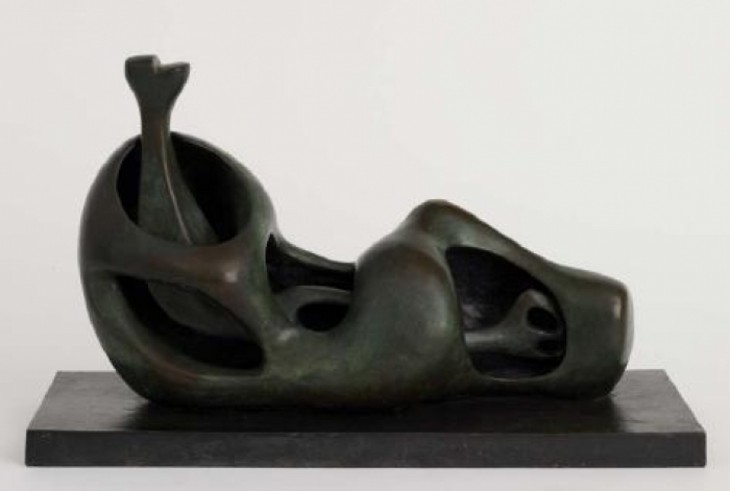

Working Model for Reclining Figure: Internal External Form 1951

Arts Council

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Working Model for Reclining Figure: Internal External Form 1951

Arts Council

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In making open work sculptures Moore may have been inspired by the techniques employed by the sculptors of Benin bronzes found in what is today Nigeria. These sculptures started with a refractory clay core upon which a layer of wax was added. Once finished, the wax model was then covered by a layer of clay or other investment. Hollow bronze sculptures normally require a core that is located in position with pins during casting to ensure that core and outer mould remain evenly separated. Moore cleverly solved the difficulties inherent in this process through allowing striations and holes to connect the inside and outside of his open work sculptures. This ensured that the gaps would be filled with investment and naturally support the wax form without the need for pins. In a letter to Helen Knapp, director of the Wakefield City Art Gallery, Moore described how he made Open Work Head No.2 1950 (fig.9):

I laid my strips of wax in the pattern that they are in the finished object, then this was covered with a further layer of the mixture of plaster and ground up pottery and the whole put into a kiln so that the wax melts out and leaves a space where it was, that is, between the core and the outside plaster. This space is filled with molten bronze so that you get an exact replica of what the wax was.14

The interrelated inner and outer surfaces of a work like Working Model for Reclining Figure: Internal External Form 1951 (fig.10) also did not require a separate core as the inner and outer spaces are continuous.15

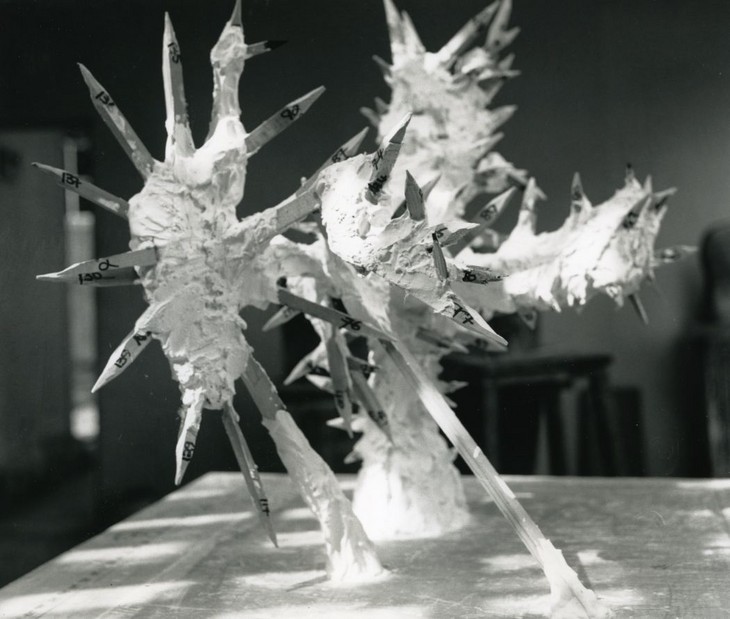

Henry Moore

Three Points 1939–40 Casting date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Three Points 1939–40 Casting date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Three Points 1939–40

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Lyndsey Morgan

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Three Points 1939–40

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Lyndsey Morgan

Records at the Henry Moore Foundation show that in 1951–2 Moore purchased quantities of casting sand, suggesting that he made bronzes in this period using the sand casting process. Before the war Moore had had his lead sculpture Three Points 1939–40 cast in iron by a local industrial foundry using this technique, and it is possible that in the 1950s he and his assistants used this cast to experiment with as they learned about bronze casting through making copies in the backyard foundry, though analysis would be needed to confirm this (fig.11). A surviving plaster, which would have been a model for the later bronze edition of ten works, shows that the points were originally joined to allow the metal to flow freely and prevent air bubbles gathering there during the casting (fig.12). The points were then separated and filed by hand in the metal cast. Moore’s interest in supervising the work of casting his bronzes soon waned, however, and he seems not to have cast works after 1952. He later explained, ‘I found the amount of time taken up doing technical jobs was preventing me from doing as much sculpture as I wanted. Besides, professional bronze casters could do the job better than I. Now I send all my sculpture away to be cast and visit the foundry if necessary’.16

Changing techniques

Henry Moore

Three-Quarter Figure 1961 (Front view)

Tate T02288

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Three-Quarter Figure 1961 (Front view)

Tate T02288

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Three-Quarter Figure (Back view)

Tate T02288

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Three-Quarter Figure (Back view)

Tate T02288

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From this period onwards Moore seems to have increasingly drawn inspiration from different ways of working with materials, allowing these to frame both the forms and subjects of his work. He used plasticine as well as wax and plaster as modelling materials, and incorporated into his models found objects such as flints and bones (both found in nearby fields and as used in cooking). For some sculptures he used press moulds17 or cast and recast objects, taking away and adding bits each time until he was satisfied. For Three Quarter Figure 1961 (Tate T02288; figs.13 and 14), for example, he made a preliminary model, probably in clay, with a head made from a found flint or stone. He then made a one-sided mould from this original into which he poured plaster to make a cast. He removed the flange produced from the overflow of plaster at the sides using a file and added further wet modelling plaster at the back (as indicated by the tool marks visible on the back) before casting the work in bronze in an edition of nine.

While he was able to create many of the models for his smaller sculptures working by himself, Moore’s ability to employ assistants in the different studios he built in the grounds of his home was to be crucial in the expansion of his production. Moore had been trained in the use of a pointing machine in his student days, but Anthony Caro later recalled that Moore did not use a pointing machine. Instead, he employed a home-made device for establishing points that appears to have involved a simple system of grids and ruler measurements. The use of maquettes that were subsequently scaled up was, of course, an entirely traditional process. Moore’s pre-war protestations about the value of working directly with materials did not, and could not, apply to the making of bronzes, and it seemed that the wheel had come full circle, as Bernard Meadows later pointed out: ‘I think there was a far greater similarity between what he did and what he was against. The sculptors who had worked before worked in exactly the same way’.18

Henry Moore

Three Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1961–2

Tate T02289

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Three Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1961–2

Tate T02289

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Armature for Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer in Moore's studio 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.16

Armature for Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer in Moore's studio 1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Foundries

Moore continued to make small editions throughout his career using several London foundries, including Galizia, Fiorini and Carney, and the Art Bronze Foundry. From 1951, however, he began to produce larger works requiring foundries specialised in this type of work. As the experience of casting Family Group 1948–9 had shown Moore, there was little foundry expertise available in Britain for casting larger sculpture, with the exception of the Morris Singer Foundry in Basingstoke. He also needed to distribute his casting commissions to ensure that he was able to meet client demand. Moore consequently worked with the well established art foundries of Rudier and Susse Frères in Paris. In 1959 Moore wrote to Paul Elek, publisher of Elek Books, about the Susse foundry:

I don’t know that this foundry is any cheaper that the English foundries – I go to them because they are most experienced and reliable for large over-life-size sculptures, and because I have to spread my casting over three or four foundries in order to get the work done by the dates required. When I send anything to Susse, in Paris, it is usually because I want two or three casts of it, otherwise the transport of the original [plaster] to Paris, and the cast to be returned make it more expensive that having it cast in England. Also the Susse foundry is used by so many sculptors that there is quite a long waiting period before they can undertake any new work.21

Other factors, such as the possibility of having a good working relationship, many also have played a role. André Susse was particularly welcoming to artists, allowing them space to work within the foundry wax workshops to make finishing touches to the wax copies of their original plaster models. In the indirect lost wax casting process a mould is made of the artist’s plaster model. Melted wax is poured into this mould and swilled around to make a hollow shell. The artist can then check the surface of the wax, make minor changes or inscribe his signature into the wax (Moore ensured that he always went and checked the waxes before casting occurred). The hollow wax model is filled on the inside to form a core and small pins are inserted which bridge the inside and outside of the mould. The wax model is then entirely encapsulated in investment, which, when dry, is placed in an oven so that the wax can be melted out, leaving the pins still holding the core in place. In this indirect lost wax process the artist’s model is not destroyed, as it is in the direct lost wax process.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960, cast 1961–2

Bronze

object: 1250 x 2900 x 1375 mm

Tate T00395

Purchased 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Henry Moore OM, CH

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960, cast 1961–2

Tate T00395

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Henry Moore's Two-Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960

Tate T00395

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.18

Detail of Henry Moore's Two-Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960

Tate T00395

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Throughout the early 1950s Moore continued to use the Susse Frères Foundry regularly, but when André Susse died he looked for new founders. Moore was then represented by the Marlborough Fine Art Gallery, London, whose owners introduced him in 1958 to Hermann Noack III of the Noack foundry in Berlin. Moore later called Noack ‘the best bronze caster I know’ and it seems that his foundry, perhaps more than any other, understood what Moore wanted in terms of finish and quality.22 Texture was hugely important to Moore, as can be seen in a work such as Two-Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960 (Tate T00395; figs.17 and 18). This would have been cast at the Berlin foundry in several sections, most likely using the indirect lost wax process, and then welded together (sand casting could not produce the level of surface detail shown here, with the chisel marks that Moore made in his original plaster faithfully reproduced). When he first worked for Moore Noack was already using argon arc welding which allowed him and other founders to achieve better joins. This in turn allowed the casting of more and smaller parts using the lost wax process.

The patina of his bronzes was an area in which Moore was closely involved. ‘The addition of the patina is of great importance, and something which I must consider and evolve myself’, he said in 1960. ‘My own patina is, of course, a preliminary to the one which nature will herself supply in time. Meanwhile the exercise of my own hand in this destiny is imperative.’23 When a bronze is first cast, its surface is cleaned of any residues from the mould, leaving the bare metal surface that is a pinkish gold colour. The bronze may be left with the surface as cast or it may be polished to a bright finish. Bronze sculptures left outdoors will gradually acquire a colour that progresses to a pale green over time as the components of the bronze alloy react with the atmosphere to produce coloured chemical compounds. In the foundry chemicals can be applied to mimic a naturally aged finish or to create completely new effects. This is typically done by a specialist patinator and the secrets of the processes and techniques used tend to be jealously guarded within the profession.

While patinas have traditionally been applied to add depth to the colour of newly cast bronze, they also have a practical function in that they help to hide weld lines and repairs made after casting. In the Renaissance it was common for bronzes to be patinated a rich dark brown, often using a dark varnish created with oils and heat rather than chemicals. Green patinas started to become more fashionable in the early twentieth century and were aimed at imitating bronze sculptures found in archaeological sites. In architecture and the decorative arts there was also a desire to use chemicals to emulate the green colour that occurred naturally on copper roofs and spires through natural weathering. A number of research articles about this were published in the 1920s and 1930s and this information may well have reached the art foundries, leading to more varied and experimental patinas. The appearance of chemical patinas can be altered by rubbing them back to reveal underlying colours, while the addition of further layers of patina tinted wax or lacquer can also add veils of colour.

Although patination is traditionally left to the bronze foundry, Moore said in 1960 that he had the foundry send his early casts to him in his studio so that he could patinate them himself:

I like working on all my bronzes after they come back from the foundry. A new cast to begin with is just like a new-minted penny, with a kind of slight tarnished effect on it. Sometimes this is all right and suitable for a sculpture but not always. Bronze is very sensitive to chemicals, and bronze naturally in the open air (particularly near the sea) will turn with time and the action of the atmosphere to a beautiful green. But sometimes one can’t wait for nature to have its go at the bronze, and you can speed it up by treating the bronze with different acids which will produce different effects. Some will turn the bronze black, others will turn it green, others will turn it red.24

It is not known how he learned the craft of patination but it is probable that there was enough published literature available that he could at least begin experimenting for himself and gradually acquire the necessary skills. His accounts for this period do not show him ordering chemicals for patination but he could have obtained at least some of the materials he needed over the counter in chemists or hardware shops. However, the final results of patination, even for experienced craftsmen, can be unpredictable (and sometimes dependent upon weather conditions). In a handwritten addition to a letter to the John Rothenstein, the Director of the Tate Gallery, just five days before the opening of his 1951 retrospective, Moore wrote about his efforts to complete the patination of the Tate’s cast of Family Group: ‘the patina is still being a problem, but I hope to have it more or less alright by this Monday – but if it’s not, it can still be changed’.25

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.19

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964

Tate T02299

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Double Oval 1966

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Becky Dockerty, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.20

Henry Moore

Double Oval 1966

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Becky Dockerty, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.1: Points 1964

Tate T02298

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.21

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Way Piece No.1: Points 1964

Tate T02298

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore interest in the processes and techniques of bronze casting had led him to become a master of the medium, one who was intimately aware of the interplay of matter and form, texture and colour. At first he was led by curiosity and expediency but it seems he soon appreciated how technique could itself become generative of form. As discussed above, his experiments in creating lead sculptures in his backyard foundry influenced his formal vocabulary and allowed him to discover ways in which metal casting could be innovative and experimental, rather than simply reproductive and traditional. In Moore’s hands bronze was not an antithesis of stone or wood carving: carving, scraping and grating his plaster models allowed him to create texture in his finished bronzes that matched anything he could achieve in his stone or wood pieces, while many of his patinas suggested natural textures and weathering. Moore’s shift from direct carving in the interwar years to bronze casting in the decades following the Second World War has been seen as marking a sea-change in his practice, but analysis of his approach to bronze suggests that were in fact many more continuities than have been thought.

Notes

See Judith Collins, ‘Moore and Concrete’ in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Research Publication, 2015, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/judith-collins-moore-and-concrete-r1172059 , accessed 03 March 2015.

See Alex J. Taylor, ‘Henry Moore and the Values of Business’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, 2015, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/alex-j-taylor-henry-moore-and-the-values-of-business-r1151298 , accessed 09 September 2015.

Donald Carroll, The Donald Carroll Interviews, London 1973, p.35, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.229.

Peter Fuller, ‘Anthony Caro Talks about Henry Moore’, Modern Painters, vol.1, no.3, Autumn 1988, p.6.

‘Central School of Arts and Crafts’ in Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951, University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/organization.php?id=msib2_1212166601&search=central%20school%20of%20arts%20and%20crafts , accessed 10 September 2014.

See Robert Harding and Michael Phipps, Henry Moore’s Backyard Foundry: An Interim Report, unpublished work-in-progress, the Henry Moore Foundation 2011.

Transcript of interviews with Bernard Meadows 1994–96, conducted with Julie Summers. p33–34, 45. Bernard Meadows Archive at the Henry Moore Foundation.

This process is sometimes called ‘gulleting’. See Duncan James, A Century of Statues: The History of the Morris Singer Foundry, London 1984, p.28.

Press moulds are created by pressing a hard object into a softer material, such as clay, and then releasing the object, leaving an imprint. This method creates a mould in relief rather than a three-dimensional mould.

Richard Cork ‘Bernard Meadows Remembers Henry Moore’, Apollo, October 1988, pp.242–7, quoted in Wilkinson 2002, p.233.

Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, New York, November 1960, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, London 2002, p.226.

Mervyn Levy, ‘Henry Moore: Sculpture Against the Sky’, Studio International, May 1964, p.179, republished in Wilkinson 2002, p.236.

Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen are sculpture conservators

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen, ‘Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www