Turner Bequest CLVIII 1–69a

Sketchbook bound in boards, covered in parchment

69 leaves and 2 paste-downs of white wove paper; approximate page size 125 x 247 mm

Various leaves watermarked ‘J Whatman | 1814’

Numbered 159 as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest inside front cover (see main catalogue entry)

Inscribed in pencil ‘CLVIII’ inside front cover, towards top left

Inscribed in pencil, probably by early curators, ‘S56’ on front and back covers, towards top left

Stamped in black ‘CLVIII’ on and inside front cover, top right and top left respectively

69 leaves and 2 paste-downs of white wove paper; approximate page size 125 x 247 mm

Various leaves watermarked ‘J Whatman | 1814’

Numbered 159 as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest inside front cover (see main catalogue entry)

Inscribed in pencil ‘CLVIII’ inside front cover, towards top left

Inscribed in pencil, probably by early curators, ‘S56’ on front and back covers, towards top left

Stamped in black ‘CLVIII’ on and inside front cover, top right and top left respectively

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

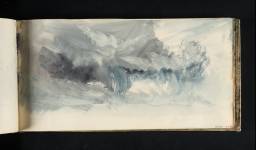

As its title suggests, this sketchbook is devoted almost entirely to the sky. In his 1909 Turner Bequest Inventory, Finberg recorded Turner’s note ’79. Skies’ on a ‘label on [the] back’,1 meaning the sketchbook’s spine; it is now detached, perhaps since the 1928 Tate Gallery flood. The sketchbook features sixty-five watercolour studies of the sky; there are also fourteen unrelated pencil sketches. David Blayney Brown has observed that the latter were ‘apparently entered from the opposite end (the back as the pages are now numbered)’.2 However, as discussed in the entry for folio 69 recto (D12526), there is the possibility that the pencil sketches predate the watercolour studies, and that Turner inverted the sketchbook to produce these studies at a later date.

It is difficult to date and locate any of the watercolour studies in this sketchbook with complete certainty. However, the locations depicted in most of the pencil sketches can be ascertained and the sketches can subsequently be dated to 1818 with some confidence. As Brown has noted, the pencil sketches are all ‘of places in London and nearby associated with Turner’s friend and patron Walter Fawkes. Several of these are datable to 1818 or later’.3 Brown observed that ‘Turner was a regular guest at [45] Grosvenor Place’, the London home of Fawkes, and was ‘adopted into the Fawkes family and taken on their outings.’4 Sketches of the annual Fourth of June celebrations at Eton College in Berkshire, which Fawkes’s sons attended5 (folios 64 verso–66 recto; D12517–D12520), and the nearby village of Salt Hill (folio 61 verso; D12511), must date from 1818, when Maria Sophia Fawkes wrote in her diary for 4 June: ‘Went to Eton to see the boat race. Dined and slept at Salt Hill. Little Turner came with us’.6

Some of the pencil sketches evidently informed works that Turner produced in 1818 or soon after. For instance, Matthew Imms’s catalogue entry for a view of Windsor Castle from Salt Hill that was engraved but not published in the Liber Studiorum (Tate D08171; Turner Bequest CXVIII Q) establishes folio 62 verso (D12513) as the immediate source for the Liber design. Further along in the sketchbook, folio 67 verso and folio 68 recto opposite (D12523, D12524) form a continuous view relating to Turner’s 1819 watercolour, London, from the Windows of 45 Grosvenor Place (private collection).7 Ian Warrell has noted:

Throughout 1818 Turner saw Fawkes and his second wife regularly ... when they were staying at ... 45 Grosvenor Place. Turner painted a watercolour showing the view from the upper rooms of the house, looking out across the gardens of Buckingham House (now Buckingham Palace), with the spires of the City churches in the distance. In April 1819 the East Drawing Room became the venue for an exhibition of Turner’s work, showcasing forty of the technically accomplished watercolours he had painted for Fawkes over the previous ten years. The universally positive reviews ensured that the event was a popular triumph.8

Folio 69 verso (D12527) likely shows the very drawing room that this exhibition was hung in.

It seems probable that the skies depicted in the watercolour studies were all observed in England around the same time as the pencil sketches were produced. Cecilia Powell had previously suggested that the sketchbook as a whole was ‘datable to the years between 1818 and 1822’, adding that it ‘was probably used in Italy’ on Turner’s first trip to the country in 1819.9 But Warrell has more recently proposed that the sketchbook was probably only used in England, observing: ‘The earliest of the sequence [of sky studies] have the damp breeziness of English skies ... it is just possible that the vibrant sunsets later on were observed during Turner’s tour of Italy; however, the unusual atmospheric conditions following the volcanic eruption of [Mount Tambora in] 1815 could also account for these colours’.10

Alexander J. Finberg, The Life of J.M.W. Turner, R.A. Second Edition, Revised, and with a Supplement, by Hilda F. Finberg, revised ed., Oxford 1961, p.252.

Andrew Wilton, The Life and Work of J.M.W. Turner, London 1979, pp.356–7 no.498 as ‘London, from the windows of 45 Grosvenor Place, when in the possession of W. Fawkes’, c.1819, reproduced.

Brown has noted:

On 10 April 1815, Mount Tambora at Sumbawa in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) erupted in the most spectacular and devasting volcanic explosion in recorded history, throwing a plume of dust and gas into the atmosphere. For almost three years, skies around the world went dark or developed a baleful, infernal glow as the sun or moon struggled to break through. Crops failed; famine, cholera and typhus ran rampant, killing millions; riots and insurrection broke out in many countries, threatening anarchy, terrifying governments and creating an apocalyptic, millenarian mood to match the prevailing gloom.11

The dramatic and long-lasting consequences of this volcanic eruption – turning 1816 into the ‘Year Without a Summer’ and darkening skies and reddening sunsets around the world for years afterwards – could therefore account for the striking appearances of the skyscapes depicted on folio 42 recto and folio 54 recto (D12490, D12502).

Regarding Turner’s sustained focus on the sky in this sketchbook, Andrew Wilton has commented, ‘studies of skies, both in pencil and in colour, occupied Turner quite intensively at different moments throughout his life’.12 Brown has noted, ‘Turner drew and painted the sky, clouds and weather all his life. ... In notes made about 1810 for his lectures as Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy, he praised “our variable climate, where the seasons are recognizable in one day ... vapoury turbulence involves the face of things [and] nature seems to sport in all her dignity”.’13 Brown added that Turner ‘was far from unique in the practice of what his fellow painter John Constable [1776–1837] called “skying”. For many artists it was part of a new quest for naturalism, an attempt to bring empirical or would-be scientific observation to bear on natural phenomena’.14 However, Gerald Wilkinson remarked that ‘Turner’s collection of skies is certainly not as scientific as Constable’s – it is more a series of cloud poems.’15

Regarding the location(s) of the featured skyscapes, Brown has concluded that, ‘In the absence of ... topographical markers, perhaps the most that can be said is that while the extended weather shock beginning in 1815 focused Turner’s interest on the sky, the studies in this sketchbook show – in varying degrees – the recovery from it; the moon shines clear again, clouds thin, the artist can venture out, sketchbook in hand.’16

Inverted relative to the sketchbook’s foliation, the paste-down on the inside of the back cover of the sketchbook (D40582) features a quick pencil sketch of clouds that is more Turner’s usual mode than the extensive watercolour studies. Towards the bottom of the paste-down are brief notes of the colours that Turner observed: ‘Yellow light. Blue Shadows. Red Crimson Light.’ There are also some faint scattered calculations in the upper-right corner.

There is no individual entry for the paste-down inside the front cover of the sketchbook. It features the executors’ note – ‘No 159 | Geo Jones’ (this is Turner’s friend, the artist George Jones [1786–1869]) – and is also inscribed in pencil by the Bequest’s assessors, Charles Lock Eastlake [1793–1865] and John Prescott Knight [1803–1881], ‘C.L.E.’ and ‘JPK’.

In terms of Turner’s own title for the sketchbook, Turner scholar David Hill initially suggested that the artist probably added his sequence of numbered and annotated paper spine labels during a general review of his sketchbooks in about 1821 or 1822,17 later revising this to the second half of 1824 on the dating evidence of some of the relevant books.18 Warrell has subsequently reasoned that the process began in 1823, ending in the summer of 1824.19

Brown 2016, p.5, quoting lecture notes from John Gage, Colour in Turner: Poetry and Truth, London 1969, p.213. For more on British artists taking the sky as their subject see Anne Lyles, ‘“That immense canopy”. Studies of Sky and Cloud by British Artists c.1770–1860’ in Constable’s Clouds, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland and National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, 2000, pp.135–50.

See David Hill, ‘The Landscape of Imagination and the Sense of Place: Turner’s Sketching Practice’ in Maurice Guillaud, Nicholas Alfrey, Andrew Wilton and others, Turner en France, exhibition catalogue, Centre Culturel du Marais, Paris 1981, pp.143, 147 note 34.

See David Hill, Turner on the Thames: River Journeys in the Year 1805, New Haven and London 1993, p.176 note 79.

Technical notes

With regards to the Whatman watermark, Bower added:

Besides the normal watermarks, pages 5, 6, and 12 in this sketchbook also show ‘ghost’ marks, where the impression of a watermark has transferred to another piece of paper, either in pressing at the mill, during the making of the paper, or, more rarely, from the pressure exerted during the binding of the book. Occasionally one finds in books the ghostmark of one maker transferred from a sheet of his paper to the surface of another watermarked sheet from a different maker used in the same book.21

How to cite

Caitlin Doley, ‘Skies Sketchbook c.1818’, sketchbook, July 2024, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, October 2024, https://www