Henry Moore OM, CH Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Image 1 of 12

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Maquette for Figure on Steps

1956

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

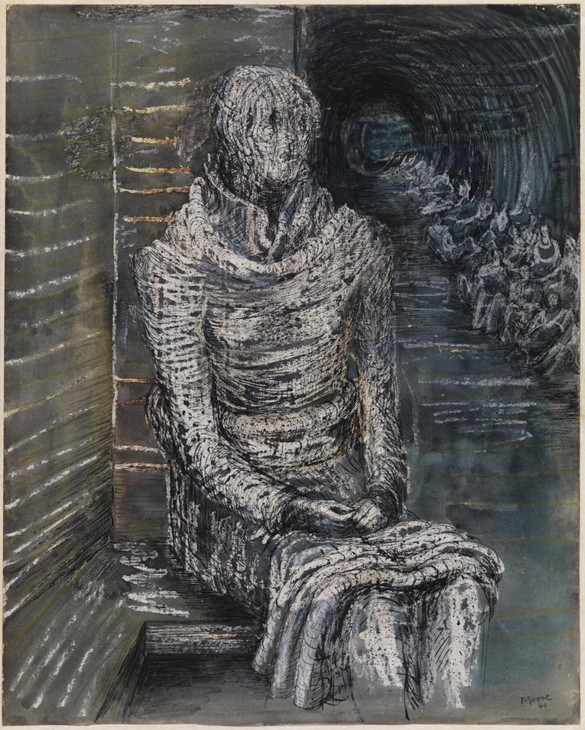

Maquette for Figure on Steps is a preparatory model for a much larger outdoor sculpture. It is part of a series of works dating from the mid-1950s in which a figure is positioned on or against an architectural feature, while the folds in the drapery demonstrate the influence of ancient Greek sculpture on Moore’s work at the time.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Maquette for Figure on Steps

1956

Bronze

167 x 182 x 163 mm

Presented by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, accessioned 1994

Number 10 in an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T06828

Maquette for Figure on Steps

1956

Bronze

167 x 182 x 163 mm

Presented by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, accessioned 1994

Number 10 in an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T06828

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler in November 1956, by whom presented to Tate in 1974, accessioned 1994.

Exhibition history

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, no.97.

2004–5

Cubism and its Legacy: The Gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, Tate Modern, London, May–November 2004; Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, December 2004–May 2005, no.44.

References

1968

Ionel Jianou, Henry Moore, Paris 1968 (another cast reproduced p.81).

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972 (another cast reproduced p.169).

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: Sixty Years of His Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983, p.124 (another cast reproduced p.83).

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Sculpture 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, no.426, p.35.

1987

Henry Moore: Maquettes and Working Models, exhibition catalogue, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City 1987, p.22 (another cast reproduced p.12).

2000

Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000 (another cast reproduced pl.24).

2004

Giorgia Bottinelli, ‘Maquettes’ in Jennifer Mundy (ed.), Cubism and its Legacy: The Gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2004, pp.84–5, reproduced p.85.

Technique and condition

Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956 is a small bronze sculpture of a female figure seated on a stepped bronze base. It was cast using a mould taken from an original model, which Moore probably sculpted from clay or plaster. This cast was made in 1956 at the Fiorini foundry in London, and is one in an edition of ten plus one artist’s copy. The complex and highly realistic folds of the figure’s dress suggest that Moore may have used real textile in his original model, perhaps consolidating it so that it set and hardened in place (fig.1).

1956 Detail of folds on dress of Maquette for Figure on Steps

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

1956 Detail of folds on dress of Maquette for Figure on Steps

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of feet of Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of feet of Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Marks produced by light modelling, such as the delicate incisions on the figure’s feet, have been directly reproduced in bronze from Moore’s original model (fig.2). The quality of the cast, along with the small fragments of casting investment retained in the folds of the drapery, suggest that the figure was cast using the traditional lost wax technique. There are some small chasing marks where seams and flashes from the cast were removed and blended with the surrounding surface (fig.3), but there is otherwise no evidence of other post-cast finishing.

Detail of casting seam on inner right arm of Maquette for Figure on Steps 1959

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of casting seam on inner right arm of Maquette for Figure on Steps 1959

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of base of Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of base of Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

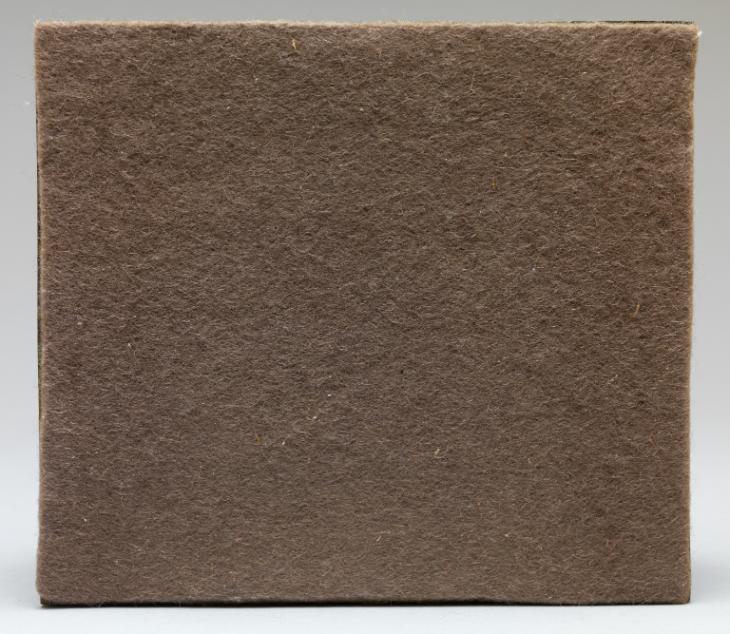

The stepped base has a slightly granular surface texture, suggesting that it was sand cast. File marks at the edges of the steps show where they were sharpened after the bronze was cast (fig.4). The fixings that have been used to attach the figure to the steps are obstructed by a layer of felt covering the underside of the base. However, a single screw thread is visible connecting the left buttock of the seated figure to the step below it. The hands make contact with the steps but do not appear to be fixed. There are no inscriptions or foundry marks on the base.

The bronze was artificially patinated by applying chemical solutions to the surface that reacted with the bronze to produce coloured compounds. A dark brown patina bordering on black was applied to the figure, probably using a solution of potassium polysulphide (known in foundries as ‘liver of sulphur’). This dark colour was then rubbed back on the higher and more prominent areas of the surface with a light abrasive, exposing the original colour of the cast bronze. A second layer of a more translucent, lighter brown patina was then applied to produce the finished effect. Finally, a layer of wax would have been applied to protect the surface.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956 is a small bronze sculpture of a seated female figure on a stepped bronze base. As its title suggests, this work served originally as a preparatory model for a much larger version of the sculpture, designed to be displayed outdoors.

Henry Moore

Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956 (side view)

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956 (side view)

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The figure sits near the top of the flight of steps and faces forward while her legs extend to her right and her head looks past her left shoulder (fig.1). Moore has arranged the body on a gentle diagonal, which moves from the feet upwards and across the body to the woman’s left shoulder, as if following the trajectory of her gaze. This diagonal composition is exaggerated by the irregular proportions of the figure’s body, in particular the thighs, which are longer than the torso (fig.2). Much of her weight is placed on her left hip and buttock, with the result that her right hip and leg are slightly higher.

1956 Detail of folds on dress of Maquette for Figure on Steps

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

1956 Detail of folds on dress of Maquette for Figure on Steps

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of feet of Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of feet of Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In contrast to her thin limbs, the woman’s torso is broad and bulky. She wears a sleeveless, knee length dress, the front of which is crinkled and clings to her body (fig.3). Two small breasts are discernable on her chest, which, when seen from the side, leans slightly forward. Her arms are particularly thin and reach backwards behind her torso where her small stump-like hands rest on the top step. The legs are slightly thicker and can be identified beneath the folds of her dress, which sags in the gap between them. Her left leg tucks underneath the right, but they do not touch. Toes have been demarcated by short lines incised into her two paddle-like feet (fig.4). The back of the figure is heavily textured, demonstrating how Moore applied daubs of plaster to the original model from which this bronze was cast (fig.5).

The figure has a distinctive block-like head, for which a prominent right angle represents the nose, separating the two flat sides of the face, which features incised eyes, nostrils and a mouth (fig.6). Hair has been rendered by overlapping lumpy masses on the rear of the head that project sideways from the right side of her head, and downwards towards her thick neck.

Origins and facture

Henry Moore

Seated Figure 1929

Cast concrete

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Seated Figure 1929

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

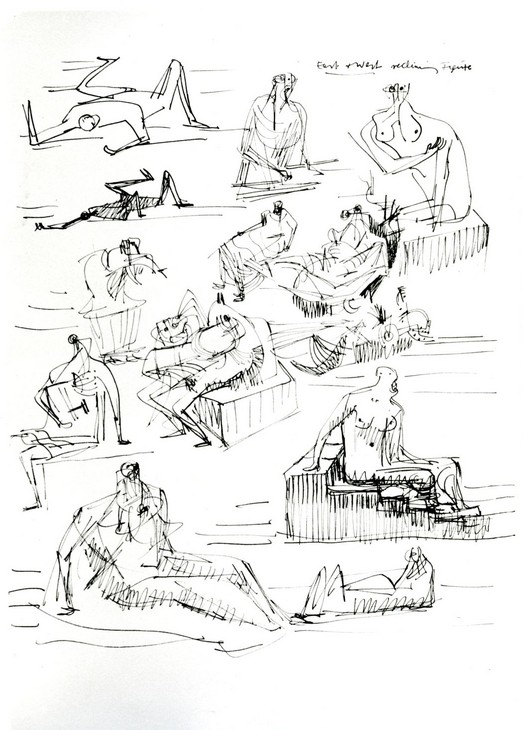

Throughout his career Moore claimed to have little interest in designing sculptures for architectural settings. Instead he preferred to situate his larger works in the open air and often in natural landscapes. Nonetheless, Moore had incorporated architectural features such as walls and steps in his drawings since the early 1930s, in which he experimented with different compositional arrangements afforded by architectural backdrops and bases (fig.8). However it was not until 1955 that the subject of the solitary female figure on steps – distinct from his standing or reclining figures and seated family groups – underwent sustained examination in three dimensions.1 In May of that year Moore was approached to propose a large-scale sculpture for the new Unesco headquarters in Paris being designed by architect Marcel Breuer.2 As part of his preparations for the commission Moore made numerous sketches of figures in architectural settings, including Figure Studies 1955–6 (fig.9), which presents fourteen figures depicted either lying, reclining or sitting. In the lower right of the page is a figure positioned at the top of a flight of steps, the subject and form of which closely resembles Maquette for Figure on Steps. Although it is unclear whether Maquette for Figure on Steps was seriously considered for the Unesco commission, Moore’s biographer Roger Berthoud identified it as one of eleven maquettes made between 1955 and 1956 that present a female figure seated on steps, a bench or against a wall, which he referred to as ‘the daughters of Unesco’.3

Henry Moore

Female Nude Seated on Steps with Dog, Classical Building Beyond 1930

Brush drawing in grey ink, with red wash, black chalk and graphite on paper

344 x 429 mm

British Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Female Nude Seated on Steps with Dog, Classical Building Beyond 1930

British Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Figure Studies 1955–6

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Figure Studies 1955–6

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore would have used his sketches as the basis for a plaster model of Maquette for Figure on Steps. Using an internal wire frame as a support, plaster would have been built up, and details such as the facial features would have been modelled or incised into the plaster. It is likely that Moore created the plaster model in 1956 in his small sculpture studio on the grounds of his home, Hoglands, in Perry Green, Hertfordshire. Once a plaster maquette was finished Moore often left it on view in his studio to establish whether the design could hold his interest over a period of time. The plaster version of Maquette for Figure on Steps evidently did, as it became the template for the enlarged Draped Seated Woman 1957–8 (Tate L01444; fig.10).

Henry Moore

Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In 1956 the plaster model of Maquette for Figure on Steps was sent to the R. Fiorini & J. Carney Foundry in London to be cast in bronze. The owner, Remo Fiorini, had formerly traded under the name Fiorini Art Bronze Foundry, but in 1956 went into partnership with John Carney; it is unclear whether this example was cast before or after the change to the foundry’s name. Moore had previously commissioned Fiorini to cast his Family Group 1949 (Tate N06004) and, although the foundry had initially experienced problems casting particularly large works, Moore continued to employ them throughout the 1950s and early 1960s.

The quality of the cast, along with the small fragments of casting investment retained in the folds of the drapery, suggest that the figure was cast using the traditional lost wax technique. After casting, any accidental flaws in the bronze would have been repaired and casting seams would have been removed. Once Moore was satisfied with the finished bronze cast he would decide what patina, or surface colour, to give the sculpture. A patina is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze. The surface of Maquette for Figure on Steps was first applied with a layer of dark brown, almost black patina. This was subsequently rubbed back so that the original coppery colour of the bronze could be seen on the sculpture’s high points, including the upper ridges of the drapery and the figure’s shins, breasts and neck.

Maquette for Figure on Steps is numbered 426 in the artist’s catalogue raisonné and was cast in an edition of ten plus one artist’s copy.4 Moore’s sales record book shows that Gustav Kahnweiler, the original owner of Tate’s cast, collected number eleven in the edition on 19 November 1956. However, a later typed page lists the work in Tate’s collection as the tenth cast in the edition.5 This is probably a consequence of a change to the numbering of the series with the intention of ensuring that number eleven could be identified as the artist’s copy. Other casts are held in the Sprengel Museum, Hannover, the Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. The remaining casts are believed to be held in private collections.

Sources and precursors

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3

Bronze

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jonty Wilde, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jonty Wilde, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Drapery played a very important part in the shelter drawings I made in 1940 and 1941 and what I began to learn then about its function as form gave me the intention, sometime or other, to use drapery in sculpture in a more realistic way than I had ever tried to use it in my carved sculpture. And my first visit to Greece in 1951 perhaps helped to strengthen this intention ... Drapery can emphasise the tension in a figure, for where the form pushes outwards, such as on the shoulders, the thighs, the breasts etc., it can be pulled tight across the form (almost like a bandage), and by contrast with the crumpled slackness of the drapery which lies between the salient points, the pressure from inside is intensified.

Drapery can also, by its direction over the form, make more obvious the section, that is, show shape. It need not be just a decorative addition, but can serve to stress the sculptural idea of the figure.

Also in my mind was to connect the contrast of the size of folds, here small, fine, and delicate, in other places big and heavy, with the form of mountains, which are the crinkled skin of earth. (The analogy, I think, comes out in close-up photographs taken of the drapery alone).6

Moore was evidently keen to downplay the notion that his use of drapery was decorative, instead proposing that it had a formative role in the presentation of the sculpture in three dimensions. Drapery could convey tension and repose, and it could both disguise and emphasise the mass and volume of a sculpture. That Moore described the act of pulling it ‘across the form’ suggests that he identified the relationship between the figure and the drapery in terms of the contrast between stillness and motion. As the critic Ionel Jianou noted of Moore’s draped figures in 1968, ‘the drapery contributes to the quivering life of the sculpture’.7

Henry Moore

Woman Seated in the Underground 1941

Tate N05707

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Woman Seated in the Underground 1941

Tate N05707

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The psychologist Erich Neumann identified the use of drapery in Moore’s sculpted seated women as ‘a variation of the blanket motif [seen in the Shelter Drawings, which] gives the whole figure an ease of line that expresses her earthbound tranquility in an almost classical way’.9 Neumann proposed that the draped figures in Moore’s sculptures and drawings, expunged of drama in gentle repose, are symbols of safety, embodying the collective desire of humanity for a peaceful alternative to war. He concluded that:

experiencing mankind as a collectivity during the war, he [Moore] saw how horror and the void drove them to seek shelter in the depth of the Earth Mother, and he gave visible and godlike form to the collective forces of annihilation that threaten the living. He also saw that art is the assertion and manifestation of the universally human, and that experience of this is the first step toward the conscious realization of a unitary culture beyond race, nation and time.10

Moore also recognised the importance of his first and only visit to Greece in 1951 as a stimulus for his draped women. Moore travelled there in February 1951 to attend the opening of an exhibition of his work at the Zappeion Gallery, Athens, organised by the British Council, but also took the opportunity to visit the country’s museums and ancient sites. While in Athens he visited the National Museum at least four times and the National Gallery once, as well as the various ancient structures clustered at the top of the Acropolis. In 1960 Moore recounted that:

there was a period when I tried to avoid looking at Greek sculpture of any kind. And Renaissance. When I thought that the Greek and Renaissance were the enemy, and that one had to throw all that over and start again from the beginning of primitive art. It’s only perhaps in the last ten or fifteen years that I began to know how wonderful the Elgin Marbles are.11

Photographs of a Greek classical statue from the Nereid Monument (fig.13), dating from the second century BC, were reproduced in the 1981 publication Henry Moore at the British Museum. For this book Moore selected and discussed artworks from the British Museum’s collection that had influenced his work, and stated of the Greek sculpture:

The drapery here is so sensitively carved that it gives the impression of light, flimsy material, wet with spray, being blown against the body by the wind. It shows how drapery can reveal the form more effectively than if the figure were nude because it can emphasise the prominent parts of the body, and falls slackly into the hollows. This is something I learned when I came to do the Shelter drawings, in which all the figures are draped. Before then I avoided using drapery because I wanted to be absolutely explicit about shapes and forms. I so admire the Greek sculptor who had the vision and the ability to make of stone something so apparently flimsy as the drapery on this figure.12

Although Moore selected the statue from the Nereid Monument for inclusion in his book, the seated figure of Hestia from the Parthenon’s East Pediment in the British Museum (fig.14) – one of group of works formerly known at the Elgin Marbles – may have been a more immediate source for the design of Maquette for Figure on Steps. The scholar Roger Cardinal has compared the formal characteristics of the ancient Greek sculpture and the enlarged Draped Seated Woman, remarking of the former: ‘she seems poised and alert. Her robes seem to flow freely across her mature body, both shaping and shaped by massive contours. Especially relevant to our theme is the way the drapery crosses between her parted knees, which dictate a passage from rounded smoothness to disjunct fold and crumplings and back again.’13

Figures of three goddesses (Hestia, Dione and Aphrodite) from the east pediment of the Parthenon, Athens c.438–432 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.14

Figures of three goddesses (Hestia, Dione and Aphrodite) from the east pediment of the Parthenon, Athens c.438–432 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

For the critic John Russell, however, Moore’s 1954 statement in fact ‘disposes altogether ... the idea that the draped statues owe anything substantial to Greek art’.14 Highlighting the artist’s reference to the ‘crinkled skin of earth’, Russell proposed that Moore was associating the drapery, and by analogy the female figure, with the landscape and thus developing an area of enquiry that he had already explored in detail, particularly in his pre-war reclining figures. Elaborating on these parallels, Russell claimed that Moore used drapery,

to romantic ends that would have been incomprehensible to the Greeks. The ‘crinkled skin of the earth’ was not something that they would have thought of as a metaphor for the folds of costume, but it was one of the quintessential metaphors for emotional states in the England of the 1940s and 1950s. Look at John Piper or Geoffrey Grigson on the derivations of British Romantic painting and you will find, over and over again, typographical references of this sort: drapery, for Moore, was another way, and a new one, of mediating between landscape and the human body.15

The Kahnweiler Gift

Maquette for Figure on Steps was presented to the Tate by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler.16 In the 1950s and 1960s the Kahnweilers were among the few art collectors in the United Kingdom who actively supported the work of European modern artists and they amassed a large collection of paintings and sculptures by artists including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Fernand Léger. Partly as a result of their friendship with the Tate director Sir John Rothenstein and with his successor Sir Norman Reid they decided to leave their entire art collection to the gallery after their deaths. A Trust Deed was signed in 1974, immediately after which a group of works were passed over to Tate. Gustav died in 1989 and the remaining works, including Maquette for Figure on Steps, were accessioned into the Tate’s collection in 1994 following Elly’s death in 1991.

It is not known how or when the Kahnweilers first met Henry Moore, but they may have become familiar with his work in the late 1930s when Moore exhibited at the Mayor Gallery in London, one of the few commercial galleries that actively exhibited and supported the work of modern artists working in Britain and continental Europe. Nonetheless, by the 1950s the Kahnweilers, Moore and Moore’s wife Irina shared a warm friendship. As well as purchasing works by Moore for their own collection, Gustav acted occasionally as an agent in the sale of Moore’s sculptures. For example, in 1952 he negotiated the sale of Moore’s sculpture to the Kunstmuseum in Basel. The Kahnweilers acquired Maquette for Figure on Steps directly from Moore shortly after it was cast, and it remained in their apartment at Alderbourne Manor, Buckinghamshire, where the couple had lived since 1956, until it entered the Tate’s collection.

Prior to his death Gustav made detailed instructions regarding the Tate’s gift, and following Elly’s death a total of fifty-five artworks entered the Tate’s collection, including works by Braque, Paul Klee, Henri Laurens, André Masson and Picasso. Along with Maquette for Figure on Steps, four other sculptures by Henry Moore were included in the Kahnweiler Gift: Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956 (Tate T06824), Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (Tate T06825), Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961 (Tate T06826), and Maquette for Standing Figure 1950 (Tate T06827).

Alice Correia

November 2013

Notes

Roger Berthoud cited by Julie Summers, ‘Working Model for Draped Seated Woman: Figure on Steps 1956’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.253.

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Sculpture 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, p.35, no.426.

Henry Moore quoted in Sculpture in the Open Air, exhibition catalogue, Holland Park, London 1954, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.280.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeney, Henry Moore, New York 1946, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.42.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in James 1966, pp.47–8.

Roger Cardinal, ‘Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece’, in Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, p.37.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore and the Welfare State Dawn Pereira

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- ‘Worthy of the great tradition’: Kenneth Clark on Henry Moore Chris Stephens

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www