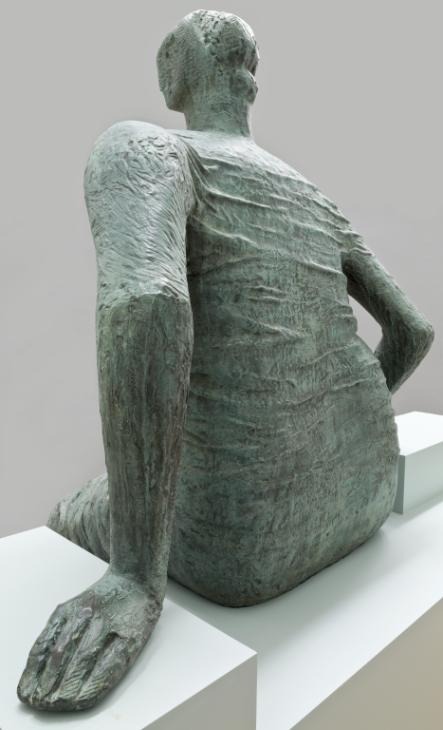

Henry Moore OM, CH Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Seated Woman 1957-8, cast c.1958-63© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Draped Seated Woman

1957-8, cast c.1958-63

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Private collection

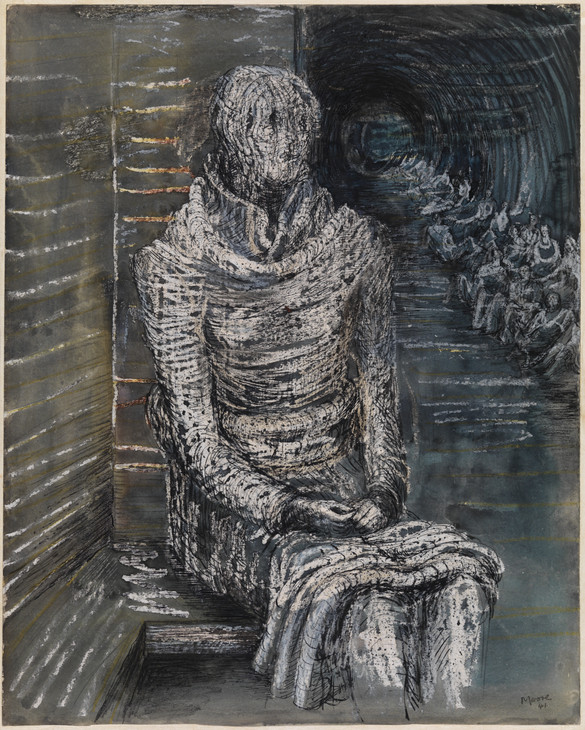

Draped Seated Woman is one of several sculptures from the 1950s that depicts a figure draped in a gown, the folds of which reveal the influence of classical Greek art on Moore’s work at this time. Deemed by some critics to represent the figure of the archetypal ‘earth mother’, Draped Seated Woman may be understood as a monument to the civil aspirations and social reforms of the post-war period.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Draped Seated Woman

1957–8, cast c.1958–63

Bronze

2280 x 2300 x 1040 mm

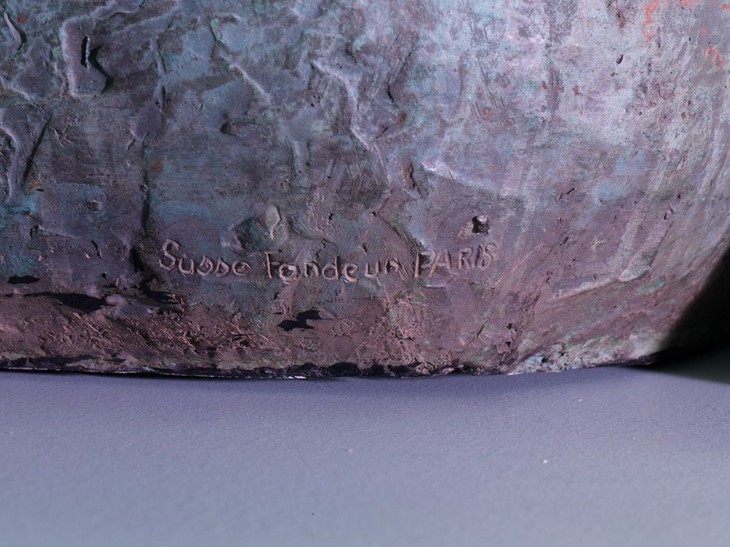

Inscribed by the artist ‘Moore’ on left buttock; ‘Susse fondeurs PARIS’ inscribed at lower edge of right buttock

Lent from a private collection 1989

Artist’s copy aside from an edition of 6

L01444

Draped Seated Woman

1957–8, cast c.1958–63

Bronze

2280 x 2300 x 1040 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Moore’ on left buttock; ‘Susse fondeurs PARIS’ inscribed at lower edge of right buttock

Lent from a private collection 1989

Artist’s copy aside from an edition of 6

L01444

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist and thence by descent; lent from a private collection in 1989.

Exhibition history

1960–1

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, Whitechapel Gallery, London, November 1960–January 1961 (?another cast exhibited no.62).

1967

Henry Moore, Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield, July–September 1967 (?another cast exhibited no.4).

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976 (?another cast exhibited).

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.42.

References

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Gallery, London 1960 (another cast reproduced no.62).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, reproduced pl.206.

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo 1968 (another cast reproduced no.96).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.127–32 (another cast reproduced pl.180).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, reproduced pls.560–2.

1976

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1976 (other casts reproduced pp.58–61, 90–4, 244–5, 400–3, 492).

1979

Alan Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979 (another cast reproduced pp.153–4, pl.127).

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983 (another cast reproduced p.89).

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Sculpture 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, p.35 (another cast reproduced pls.58–9).

1987

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, pp.178–9 (plaster cast reproduced no.127).

1998

Margaret Garlake, New Art / New World: British Art in Postwar Society, New Haven and London 1998, pp.229–30 (?another cast reproduced pl.108).

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.72.

2006

Patrick Eyres and Fiona Russell (eds.), Sculpture in the Garden, Aldershot 2006, p.116 (?another cast reproduced p.34).

2006

Christopher Marshall, ‘Between Beauty and Power: Henry Moore’s Draped Seated Woman as an Emblem of the National Gallery of Victoria’s Modernity 1959–68’, Art Bulletin of Victoria, vol.46, 2006, pp.37–49 (another cast reproduced pp.37, 41).

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007, pp.61, 72–3 (another cast reproduced p.72).

Technique and condition

Photograph of plaster version of Draped Seated Woman in Moore's studio c.1957–8

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Photograph of plaster version of Draped Seated Woman in Moore's studio c.1957–8

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The arms, legs and head of the figure are all marked with linear striations, most likely gouged into the surface when the plaster was ‘cheese hard’ rather than fully set. Parallel striations on the neck and forehead may have been made with a surform or grater (fig.2), while more clearly individuated marks such as those on the right leg were made individually, perhaps using a gouge or chisel (fig.3).

Detail of face of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of face of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of right leg of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of right leg of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In contrast, the texture of the folded drapery was achieved by using a spatula to apply wet plaster to the surface (fig.4). It is possible that its heavily wrinkled appearance was produced by draping fabric soaked in plaster over the contours of the sculpture, which Moore then arranged and built up with further layers of plaster. Moore would have also used a spatula for the more expressive modelling of the hair (fig.5).

Detail of drapery on Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of drapery on Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of hair of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of hair of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In the mid-1950s Moore worked with a number of British foundries to cast his sculptures in bronze, but by 1958 he had learnt that these foundries often encountered difficulties when casting sculptures on a large scale. He therefore decided to employ the Susse Fondeur in Paris to cast this sculpture in an edition of seven. The techniques used to fabricate this sculpture in bronze differed slightly from those employed by British and German foundries to cast other bronzes by Moore.

Plaster sculptures of this size are usually cut into sections at the foundry and cast in bronze individually. Traces of casting investment embedded in the rear surface of the figure’s right hip suggest that this sculpture was cast using the lost wax technique (fig.6). After each section of the sculpture had been cast the individual pieces would have been assembled together. Close examination of the bronze from the inside reveals a horizontal join across the hip line where the upper and lower parts of the torso are bolted together (fig.7). This join cannot be seen on the outer surface and may be concealed with a line of solder.

Detail of casting investment on Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.6

Detail of casting investment on Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Detail of internal bolts in Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.7

Detail of internal bolts in Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

The leg sections below each knee were cast separately and joined to the upper legs using roman joints, which allow two pieces of bronze to be slotted into one another. In this case an inner sleeve enabling the two parts to fit together snugly would have been cast before holes were drilled through both parts and secured with large pins. The pins are clearly visible on the inside but have been carefully blended with the surrounding surface on the outside. This technique was used to fabricate bronze sculptures in ancient times but in many foundries was eventually replaced by metal welding. However, a well-constructed roman joint retains the advantage of leaving only a very fine line between the two pieces. Furthermore, the absence of a weld line circumvents the need for the seam to be ‘chased’, or filed and textured with punches.

Detail of repairs on knee of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Detail of repairs on knee of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Freshly cast bronze is normally coloured by means of artificial patination. This involves the application of chemical solutions to the surface either with or without heat, which react with the bronze to produce various coloured compounds. This sculpture has a dense, pale green patina with brown highlights. The vertical run marks visible on the high points of the sculpture, particularly the head (see fig.2), reveal that it has been displayed outside and its patina altered by means of weathering. Bronzes left outdoors tend to develop a green patina due to naturally produced green compounds, and it is therefore difficult to identify the original colour of this sculpture. The brown highlights suggest that a brown patina was initially applied to the sculpture using a chemical such as potassium polysulphide. However, the significantly deep shade of green that has developed may indicate that the brown was a base coat over which a green patina solution, which has since intensified, was applied. That the brown highlights are mostly visible on accessible and exposed points such as the knees suggests that repeated handling of the sculpture has removed the overlying green patina in these areas. Because Draped Seated Woman was displayed outdoors it is likely that the folds of fabric in the woman’s lap would have gathered rainwater. Two small holes were drilled into the front and centre of the lap to allow water to drain away.

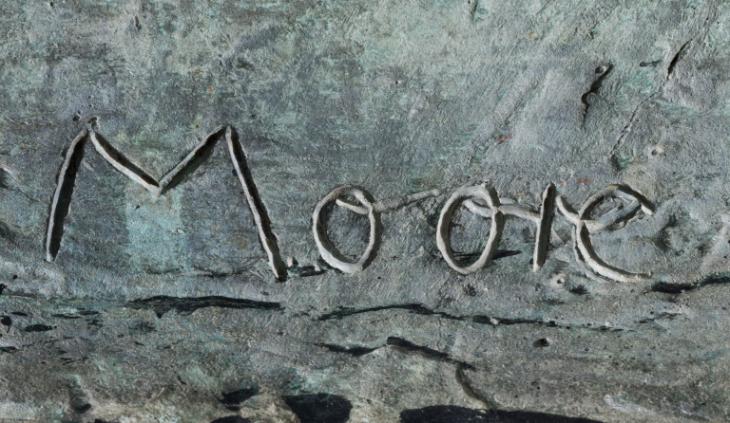

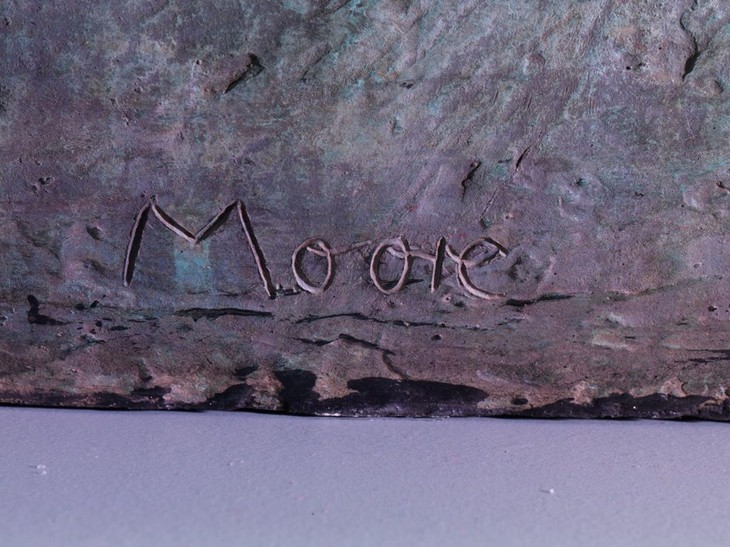

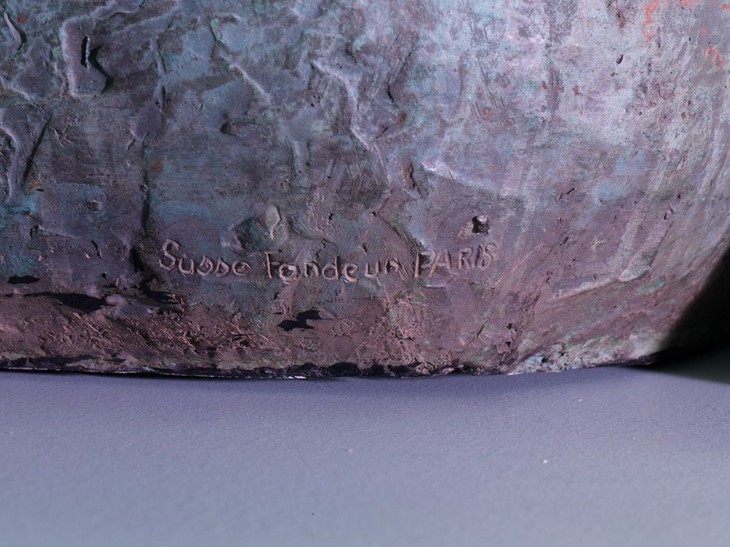

The base used for the sculpture’s display at Tate is not part of the work but was built according to a design approved by Moore and supports the sculpture without requiring any fixings. The foundry name, ‘Susse fondeurs PARIS’, is inscribed at the lower edge of the right buttock (fig.9). The artist’s signature, ‘Moore’, can be seen on the left buttock (fig.10).

Detail of foundry mark on rear of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Detail of foundry mark on rear of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of artist's signature on rear of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Detail of artist's signature on rear of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Lyndsey Morgan

January 2014

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', January 2014, in Alice Correia, ‘Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Draped Seated Woman 1957–8 is a larger than life-size bronze sculpture positioned on a stepped wooden plinth. The figure is proportioned irregularly, with a small head, extremely bulky torso and legs that span almost half the sculpture, while features such as the face, hands and feet have been rendered schematically. The woman’s body faces forward while her legs extend to her right and her head looks over her left shoulder (fig.1). Much of her weight is placed on her left hip and buttock – with the result that her right hip and leg are slightly higher – and on her left hand, which rests slightly behind her body on the top step. Moore has composed the body on a gentle diagonal, which moves from the feet up and across her body to her left shoulder.

The woman wears a sleeveless, knee length dress, which appears to cling to her body in folds, the ridges of which curve over her legs and sag between her thighs. Two small breasts are discernable on her chest. When seen from the side it is evident that she is leaning slightly forward. In comparison to her bulky body and heavy legs, her arms appear relatively thin. Her bent knees, shins and feet are uncovered and extend out to the side, with the left leg tucking under the right.

The figure has a distinctive block-like head, the flat edges of which denote the forehead and the two sides of the face (fig.2). On either side of the central angle are circular holes indicating the eyes, while nostrils and a small mouth make up the other features of the face. Hair has been rendered by overlapping lumpy masses on the rear of the head that project sideways to form a smoothed, rectangular protrusion on the right side of her head.

Henry Moore

Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of face of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of face of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Origins and facture

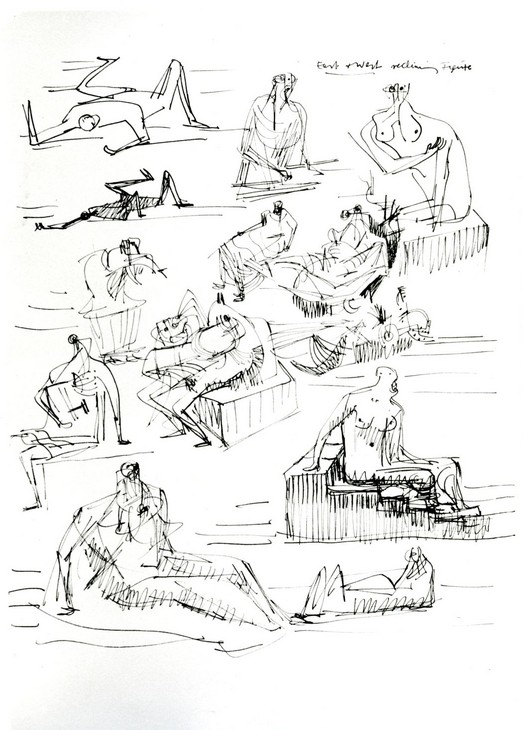

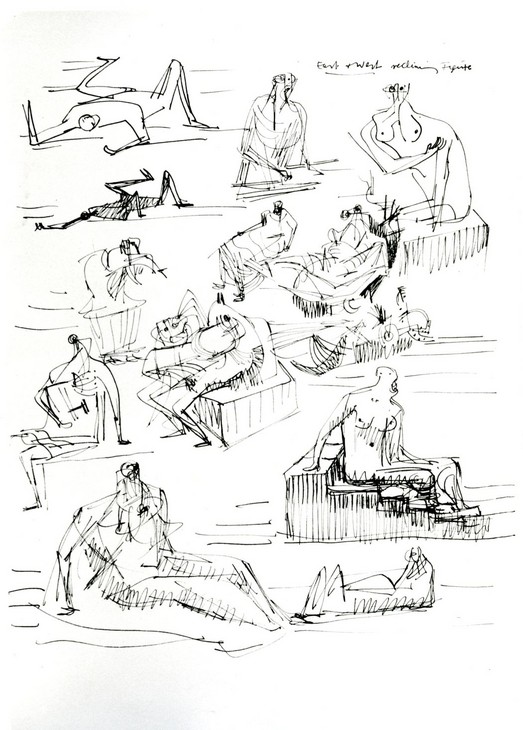

Although Moore had executed drawings of a woman seated on a flight of steps much earlier in his career, he only began to extensively examine the formal potential of the subject in the mid-1950s. This corresponded to a transitional moment in Moore’s career in which he largely replaced preparatory sketches with small models or maquettes as a means of developing the designs for his sculptures. Nonetheless, Moore made at least two pages of drawings between 1955 and 1956 that directly relate to the development of Draped Seated Woman. Figure Studies 1955–6 (fig.3) includes a sketch of a female figure seated on a flight of steps towards the lower right of the page. Although the figure does not adopt an identical pose to the large-scale sculpture, the drawing nonetheless demonstrates that Moore was thinking about the formal relationships that could be established between a stepped platform and a seated figure. In particular, the sketched figure’s arms extend backwards to rest on the top step and its body appears slightly twisted, much like the figure in Draped Seated Woman.

In 1956 Moore used his sketches as the basis for a plaster maquette, made by applying layers of plaster over an internal wire frame before modelling or incising details, such as the facial features, in the built-up surface. Moore undertook this work in the small sculpture studio in the grounds of his home, Hoglands, in Perry Green, Hertfordshire. The small plaster sculpture, known as Maquette for Figure on Steps, was later cast in a bronze edition of ten plus one artist’s copy (Tate T06828; fig.4).

Henry Moore

Figure Studies 1955–6

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Figure Studies 1955–6

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Tate T06828

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Once Moore was happy with the design of his maquette it would then be scaled up to a working model of intermediary size. The working model was also made in plaster, which was similarly built up over an internal wire armature. A scale reproduction of the maquette could be produced by measuring and charting specific points on its surface and multiplying them by a fixed ratio. It is likely that Moore first made the steps for the sculpture and then moved to working on the figure.

The working model allowed Moore to test the design of the sculpture on a slightly larger scale (fig.5). At this stage the arrangement of the limbs could still be adjusted and details such as the facial features and the folds of the drapery could be worked to a more precise finish. The plaster working model was also cast in a bronze edition at the Fiorini foundry in London. Sculptures of this size could be shown to potential clients to give them a more accurate impression of how a large-scale rendering might look. In 1983 Moore was quoted as saying, ‘most everything I do, I intend to make on a large scale if I am given the chance. So when required to make work larger, I am always pleased. Size itself has its own impact, and physically we can relate ourselves more strongly to a big sculpture than to a small one. At least I do’.1

Moore very rarely made site-specific sculptures and claimed, ‘I dislike the idea of making a work for a particular place ... I think you should make something that is right anywhere – and then find a happy place for it’.2 The full-size version of Draped Seated Woman was originally commissioned by the city of Wuppertal, Germany, to be located outside its newly constructed public swimming baths. Precisely how delegates from Wuppertal came to select Draped Seated Woman for their city is not known, but Moore would often invite clients to choose from a selection of existing maquettes and working models in his studio or suggest the design himself.

Having agreed to the Wuppertal commission Moore would have made a full-size plaster model of the sculpture (fig.6). This enlargement would have proceeded according to a similar logic from which the maquette was enlarged to a working model, although the wire frame would have been replaced by an armature probably constructed from lengths of wood and wire netting draped in layers of scrim, a bandage-like fabric soaked in plaster. Over this structure, plaster would have been applied with trowels and spatulas. This process was carried out in the White Studio at Hoglands and it is likely that much of the labour was undertaken by Moore’s studio assistants, who at the time included Geoffrey Harris, Anthony Hatwell, Daryl Hill, Maurice Lowe and Stephen Rich. Moore was able to allocate the bulk this work to others because, as curator Julie Summers has noted, the enlargement process was ‘a scientific rather than artistic process’.3

Henry Moore

1956 Working Model for Draped Seated Woman plaster

© Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Henry Moore

1956 Working Model for Draped Seated Woman plaster

© Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photograph of plaster version of Draped Seated Woman in Moore's studio c.1957–8

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Photograph of plaster version of Draped Seated Woman in Moore's studio c.1957–8

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore found plaster to be a very useful material because it could be ‘both built up, as in modeling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.4 He used an array of tools including chisels, files and sandpaper to create different types of textures according to how wet or dry the plaster was. Discussing the development of his drapery, Moore recalled that ‘gradually I evolved a treatment that exploited the fluidity of plaster. The treatment of drapery in my stone carvings was a matter of large, simple creases and folds but the modelling technique enabled me to build up large forms with a host of small crinklings and rucklings of the fabric’.5 These different surface textures were retained in the bronze when it was cast at the foundry.

Detail of foundry mark on rear of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Detail of foundry mark on rear of Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

I don’t know that this foundry is any cheaper than the English foundries – I go to them because they are most experienced and reliable for large over-life-size sculptures, and because I have to spread my casting over three or four foundries in order to get the work done by the dates required.

When I send anything to Susse, in Paris, it is usually because I want two or three casts of it, otherwise the transport of the original [plaster] to Paris, and the cast to be returned make it more expensive than having it cast in England. Also the Susse foundry is used by so many sculptors that there is quote [sic] a long waiting period before they can undertake any new work.6

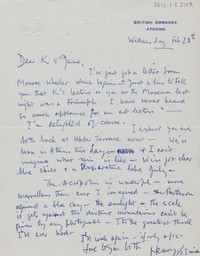

The terms of the Wuppertal commission allowed Moore to produce additional casts of the full-size sculpture for sale outside Germany. Draped Seated Woman was cast in an edition of six plus one artist’s cast. As Moore noted in his 1959 letter, casting more than one version of the sculpture at a time made the choice of Susse Frères economically viable. Correspondence held in the Henry Moore Foundation Archive suggests that Moore was adept at pre-selling his sculptures; the first version was reserved for Wuppertal and it appears that at least one other was being considered by an American client before any of the casts had been produced. On 8 April 1958 Moore wrote to the Baltimore based collector Alan Wurtzburger, who was seeking to purchase a cast of Draped Seated Woman for the Baltimore Museum of Art, stating that ‘the bronze casting of “Draped Seated Woman” which is being done by Susse in Paris is turning out to be some hundreds more than the £1,000 I had expected’.7 Moore went on to offer Wurtzburger the sculpture at a discounted price of £4,000. Making bronze sculptures of this size took considerable time, and the whole edition was cast between 1958 and 1963.

Due to its size, the sculpture would have been cast in separate parts, which were then assembled by the foundry technicians. Some sections were bolted together inside the hollow interior while others were attached using Roman joints. This technique involved slotting two sections together, drilling holes and securing them with circular plugs. Unlike welding, this system did not necessitate any further modification to the bronze surface to disguise the joints, which are almost imperceptible.

The foundry technicians would also have drilled the two circular holes near the hemline of the figure’s skirt. These holes formed part of a drainage system conceived by Moore. In 1968 the artist recounted that:

I knew that the big, draped seated figure was going to be shown out of doors and this created the problem that the folds in the drapery could collect dirt and leaves and pockets of water. I solved it by making a drainage tunnel through the drapery folds between the legs. I found that using drapery in the sculpture was a most enjoyable exercise in itself.8

Once the bronze sculpture had been cast and assembled at the foundry it was probably returned to Moore so that he could inspect the quality of its casting and make decisions about its patina. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze surface. Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin and chemicals in the air can react with these metals to change the surface colour of the sculpture. It is unclear what type of patina this sculpture had originally, but its turquoise green shades probably developed over time and from prolonged exposure to outdoor conditions. Indeed, it is likely that the visible green drip lines running down the woman’s arms were caused by rainwater reacting with the copper content of the bronze.

There are a total of seven versions of the full-size Draped Seated Woman. The other bronze casts can be found in the collections of the Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal; Yale University Gallery, New Haven; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem; Museé d’art moderne, Brussels; and Tower Hamlets Council, London. The version at Tate is the artist’s copy and has been on long-term loan to the gallery from a private collection since 1989.

Form and content

During the 1950s the single female figure seated on steps – distinct from the artist’s standing or reclining figures and seated family groups – became a persistent subject of Moore’s sculpture, particularly after 1955.9 In May that year Moore was approached to create a large-scale sculpture for the new headquarters of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) in Paris. Throughout 1955 and 1956 Moore struggled to formulate a design that would express the tenets of Unesco and assert itself against the building’s façade, designed by architect Marcel Breuer. Moore created numerous maquettes for the project, variously presenting a female figure, or groups of figures, seated on steps, or on benches, often set against a wall. Maquette for Seated Figure against Curved Wall 1955 (fig.8), for instance, presents a female figure sitting on a step in front of a curved background plane. Although it is unclear whether the maquette from which Draped Seated Woman developed was seriously considered for the Unesco commission, Moore’s biographer Roger Berthoud identified it as one of eleven maquettes made between 1955 and 1956 that he referred to as ‘the daughters of Unesco’.10

Although the Unesco commission may have catalysed the development of Draped Seated Woman, the sculpture is also closely related to Moore’s earlier Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3 (fig.9). Designed as part of a commission for the Time-Life building on Bond Street, London, where it was positioned on the roof terrace, Draped Reclining Figure was the first sculpture in which Moore incorporated rippled and ridged folds to denote drapery. Discussing this sculpture in 1954, Moore stated:

Drapery played a very important part in the shelter drawings I made in 1940 and 1941 and what I began to learn then about its function as form gave me the intention, sometime or other, to use drapery in sculpture in a more realistic way than I had ever tried to use it in my carved sculpture. And my first visit to Greece in 1951 perhaps helped to strengthen this intention ... Drapery can emphasise the tension in a figure, for where the form pushes outwards, such as on the shoulders, the thighs, the breasts etc., it can be pulled tight across the form (almost like a bandage), and by contrast with the crumpled slackness of the drapery which lies between the salient points, the pressure from inside is intensified.

Drapery can also, by its direction over the form, make more obvious the section, that is, show shape. It need not be just a decorative addition, but can serve to stress the sculptural idea of the figure.

Also in my mind was to connect the contrast of the size of folds, here small, fine, and delicate, in other places big and heavy, with the form of mountains, which are the crinkled skin of earth. (The analogy, I think, comes out in close-up photographs taken of the drapery alone).11

Drapery can also, by its direction over the form, make more obvious the section, that is, show shape. It need not be just a decorative addition, but can serve to stress the sculptural idea of the figure.

Also in my mind was to connect the contrast of the size of folds, here small, fine, and delicate, in other places big and heavy, with the form of mountains, which are the crinkled skin of earth. (The analogy, I think, comes out in close-up photographs taken of the drapery alone).11

Henry Moore

Figure Studies 1955–6

Pen and ink on paper

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Figure Studies 1955–6

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3

Bronze

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jonty Wilde, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jonty Wilde, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore was evidently keen to downplay the notion that his use of drapery was decorative, instead proposing that it had a formative role in the presentation of the sculpture in three dimensions. Drapery could convey tension and repose, and it could both disguise and emphasise the mass and volume of a sculpture. That Moore described the act of pulling it ‘across the form’ suggests that he identified the relationship between the figure and the drapery in terms of the contrast between stillness and motion. As the critic Ionel Jianou noted of Moore’s draped figures in 1968, ‘the drapery contributes to the quivering life of the sculpture’.12

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Woman Seated in the Underground 1941

Gouache, ink, watercolour and crayon on paper

support: 483 x 381 mm

Tate N05707

Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee 1946

Fig.10

Henry Moore OM, CH

Woman Seated in the Underground 1941

Tate N05707

The psychologist Erich Neumann identified the use of drapery in Moore’s sculpted seated women as ‘a variation of the blanket motif [seen in the Shelter Drawings, which] gives the whole figure an ease of line that expresses her earthbound tranquillity in an almost classical way’.14 Neumann proposed that the draped figures in Moore’s sculptures and drawings, expunged of drama in gentle repose, are symbols of safety, embodying the collective desire of humanity for a peaceful alternative to war. He concluded that:

experiencing mankind as a collectivity during the war, he [Moore] saw how horror and the void drove them to seek shelter in the depth of the Earth Mother, and he gave visible and godlike form to the collective forces of annihilation that threaten the living. He also saw that art is the assertion and manifestation of the universally human, and that experience of this is the first step toward the conscious realization of a unitary culture beyond race, nation and time.15

Moore also recognised the importance of his first and only visit to Greece in 1951 as a stimulus for his draped women. Moore travelled there in February 1951 to attend the opening of an exhibition of his work at the Zappeion Gallery, Athens, organised by the British Council, but also took the opportunity to visit the country’s museums and ancient sites. While in Athens he visited the National Museum at least four times and the National Gallery once, as well as the various ancient structures clustered at the top of the Acropolis. In 1960 Moore recounted that:

there was a period when I tried to avoid looking at Greek sculpture of any kind. And Renaissance. When I thought that the Greek and Renaissance were the enemy, and that one had to throw all that over and start again from the beginning of primitive art. It’s only perhaps in the last ten or fifteen years that I began to know how wonderful the Elgin Marbles are.16

Photographs of a Greek classical statue from the Nereid Monument (fig.11), dating from the fourth century BC, were reproduced in the 1981 publication Henry Moore at the British Museum. For this book Moore selected and discussed artworks from the British Museum’s collection that had influenced his work, and stated of the Greek sculpture:

The drapery here is so sensitively carved that it gives the impression of light, flimsy material, wet with spray, being blown against the body by the wind. It shows how drapery can reveal the form more effectively than if the figure were nude because it can emphasise the prominent parts of the body, and falls slackly into the hollows. This is something I learned when I came to do the Shelter drawings, in which all the figures are draped. Before then I avoided using drapery because I wanted to be absolutely explicit about shapes and forms. I so admire the Greek sculptor who had the vision and the ability to make of stone something so apparently flimsy as the drapery on this figure.17

Although Moore selected the statue from the Nereid Monument for inclusion in his book, the seated figure of Hestia from the Parthenon’s East Pediment in the British Museum (fig.12) – one of group of works formerly known at the Elgin Marbles – may have been a more immediate source for the design of Draped Seated Woman. The scholar Roger Cardinal has compared the formal affinities between Moore’s work and the ancient Greek sculpture, remarking that in the latter sculpture the figure ‘seems poised and alert. Her robes seem to flow freely across her mature body, both shaping and shaped by massive contours. Especially relevant to our theme is the way the drapery crosses between her parted knees, which dictate a passage from rounded smoothness to disjunct fold and crumplings and back again.’18

Statue from the Nereid Monument, Xanthos c.390–380 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.11

Statue from the Nereid Monument, Xanthos c.390–380 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Figures of three goddesses (Hestia, Dione and Aphrodite) from the east pediment of the Parthenon, Athens c.438–432 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.12

Figures of three goddesses (Hestia, Dione and Aphrodite) from the east pediment of the Parthenon, Athens c.438–432 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Although Moore emphasised the influence of ancient Greek art on the development of his draped figures, other sources for this body of work have been identified. The critic John Russell, for example, argued in 1968 that Moore’s 1954 statement ‘disposes altogether ... the idea that the draped statues owe anything substantial to Greek art’.19 Highlighting the artist’s reference to the ‘crinkled skin of earth’, Russell proposed that Moore was associating the drapery, and by analogy the female figure, with the landscape and thus developing an area of enquiry that he had already explored in detail, particularly in his pre-war reclining figures. Elaborating on these parallels, Russell claimed that Moore used drapery,

To romantic ends that would have been incomprehensible to the Greeks. The ‘crinkled skin of the earth’ was not something that they would have thought of as a metaphor for the folds of costume, but it was one of the quintessential metaphors for emotional states in the England of the 1940s and 1950s. Look at John Piper or Geoffrey Grigson on the derivations of British Romantic painting and you will find, over and over again, typographical references of this sort: drapery, for Moore, was another way, and a new one, of mediating between landscape and the human body.20

In 1960 the critic Will Grohmann identified two kinds of seated figure in Moore’s work. The first, he argued, conveyed repose and contemplation, while the second expressed ‘the moment before rising, jumping up, going into action’.21 Works such as Draped Seated Woman have generally been regarded as manifestations of the first kind, with Grohmann suggesting that ‘the relaxed figures tend towards the classical, and the tense ones toward the demonic’.22 Grohmann identified Moore’s draped women as ‘superior, modern beings, guardians of a university, a museum or a public square’, but also ultimately ‘relaxed’ in disposition.23 The art historian Kenneth Clark developed this view in 1973, suggesting that with his draped women Moore had been driven by the ‘urge to create an almost classical ideal of noble placid female beauty’.24

Henry Moore

Standing Figure: Back View c.1924

Pen and ink, brush and ink, chalk and wash on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Standing Figure: Back View c.1924

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In his analysis of Moore’s work Neumann related the maternal aspects of Moore’s large women to those of the archetypal ‘Great Mother’.28 Identifying the centrality of this archetype to ancient civilisations, Neumann described the Great Mother as a symbol of ‘nourishment, shelter and security’, and ‘the mistress of life and fertility’.29 Indeed, Neumann posited that as a fundamental trope of human consciousness the archetype, once sublimated, would soon return to prominence:

the sovereign power of motherhood determined the earliest phase of man’s development, and only later, with the growth of consciousness, was it superseded and overlaid by the significance of the father and the patriarchal values connected with the father archetype. Today a new shift of values is beginning, and with the gradual decay of the patriarchal canon we can discern a new emergence of the matriarchal world in the consciousness of Western man.30

Display and critical reception

Another cast of Draped Seated Woman was exhibited in Moore’s solo exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 1960. Curated by Bryan Robertson, the exhibition was made up of sculptures produced since 1950, and was Moore’s first major exhibition in London for five years. The critic David Thompson noted in the Times the proliferation of figures set against architectural features, including steps and walls, remarking that their poses emphasise ‘how lonely and ill at ease they really are, as much so the massive, draped figures of seated women (1957–58) which seem both calm and monumentally unrelaxed’.31 Writing in the Listener, Keith Sutton noted that the arrangement of Moore’s sculptures gave ‘the impression that the Whitechapel is, for the present, a noble and sombre anteroom to a great museum packed with treasures. We feel at once that all these works of art are in the mainstream of great historical art – as we know it from museums’.32 Sutton also suggested that ‘the visual association between this exhibition and the Elgin rooms at the British Museum is neither causal nor fortuitous. The allusions to classical forms are explicit in the works’.33 Sutton observed of Moore’s draped women that ‘the various seated and reclining goddesses are by nature indifferent to our presence, making no concessions to identification. They are as stoic as the river gods of Arcady: in their water-flowing draperies their attention is alerted by more primal echoes’.34

However, Sutton also noted how the sense of self-containment conveyed by Moore’s draped figures curtailed emotional interaction with the sculptures. Furthermore, Sutton proposed that in his use of classical drapery, Moore was making work that looked like public art, but which did not fulfil that function:

for Moore can engage classicism on more than one level. He can use it as a cloak to invoke status for a public work of art. These particular sculptures I find to be rather slenderly felt, great social occasions are eccentric to his aesthetic intentions. On the deepest level his works constantly imply formidable events, but they are concerned with forces of nature rather than of man. It is as though he were on the side of the gods.35

Sutton seemed to suggest that by using classical forms Moore sought to secure a universality for his sculptures that, by means of its lofty aspirations, in fact alienated the very public to which these works were ostensibly addressed. Although Moore was recognised as one of Britain’s foremost artists by this time, some responses to the Whitechapel exhibition registered a note of disenchantment with such aspirations. In his review of the exhibition for Art International the critic Lawrence Alloway identified a friction between the universalising thrust of Moore’s sculptures and the contemporary mood. While he acknowledged that, ‘Obviously out of the highest motives, Moore is hoping to give his public sculptures a worthy message, a stirring content’, Alloway argued that it was ultimately futile to appeal to universals in an age of ‘anguish and individualism’ characterised by the paintings of Francis Bacon and Willem De Kooning.36 Alloway argued that in drawing from the stock of classical motifs and subjects, Moore ‘revived the miming of 16th and 17th century figure sculpture’ but, as a twentieth-century artist, would never be able to approach the human figure with the same assuredness as his predecessors.37

Moore’s former assistant Anthony Caro was more direct in questioning the older artist’s apparent dominance over British sculpture. In the Observer Caro claimed that although Moore had paved the way for the next generation of artists, he had ‘paid heavily for his stardom’, noting that ‘my generation abhors the idea of a father-figure, and his work is bitterly attacked by artists and critics under forty when it fails to measure up to the outsize scale it has been given’.38 At this time Caro was a leading figure in a new style of sculpture that rejected figuration, was constructed rather than sculpted, and painted in colours emphasising its synthetic nature (see for example, Early One Morning 1962, Tate T00805). For the influential American critic Clement Greenberg, Caro’s sculpture exemplified his assertion that modern sculpture ‘has almost no historical associations whatsoever – at least not with our own civilization’s past – which endows it with a virginality that compels the artist’s boldness and invites him to tell everything without fear of censorship by tradition’.39 According to Greenberg, Moore’s work meanwhile gave the derisory ‘impression ... of something not too far from classical statuary’.40

Nonetheless, when another cast of Draped Seated Woman was acquired by the London County Council (LCC) in 1962, the sculpture became a symbol of Britain’s post-war redevelopment. The sculpture had been purchased as part of the council’s regeneration policy and was placed on a landscaped lawn in front of the newly built Stifford Estate in Tower Hamlets, London, in spring 1963. The art historian Margaret Garlake has suggested that because the Stifford Estate, which provided housing for approximately 1,700 people in three high-rise blocks, was a landmark social housing project, the LCC wanted an equally important piece of public sculpture to adorn it.41 According to the art historian Christopher Marshall, Moore’s monumental women answered ‘a deep-seated postwar need for an epic, modern, civic art that might help rebuild a shattered Europe through the reinforcement of universal humanist values that reconnected the individual to the landscape, both urban and natural’.42

Alice Correia

November 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983, p.13.

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126.

Henry Moore, ‘Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites’, 1955, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, London 2002, p.280.

Henry Moore, letter to Alan Wurtzburger, 8 April 1958, E. Kirkbride Miller Art Research Library, Baltimore Museum of Art, Alan and Janet Wurtzburger Papers, Box 1, Folder 36, WP1.36.10, http://cdm16075.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15264coll9/id/18 , accessed 17 December 2013.

Roger Berthoud cited by Julie Summers, ‘Working Model for Draped Seated Woman: Figure on Steps 1956’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.253.

Henry Moore quoted in Sculpture in the Open Air, exhibition catalogue, Holland Park, London 1954, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.280.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeney, Henry Moore, New York 1946, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.42.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in James 1966, pp.47–8.

Roger Cardinal, ‘Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece’, in Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, p.37.

Henry Moore cited in Hew Wheldon (ed.), Monitor: An Anthology, London 1962, pp.21–2, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.147.

Clement Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945–49, Chicago 1986, p.318.

Margaret Garlake, New Art / New World: British Art in Postwar Society, New Haven and London 1998, p.229.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and the Values of Business Alex J. Taylor

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore and the Welfare State Dawn Pereira

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- ‘Worthy of the great tradition’: Kenneth Clark on Henry Moore Chris Stephens

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

Related reviews and articles

- Keith Sutton, ‘Henry Moore at Whitechapel’ Listener, December 8 1960.

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Draped Seated Woman 1957–8, cast c.1958–63 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www