Henry Moore OM, CH Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2

Image 1 of 9

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961-2© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Reclining Figure: Bunched

1961, cast 1961-2

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

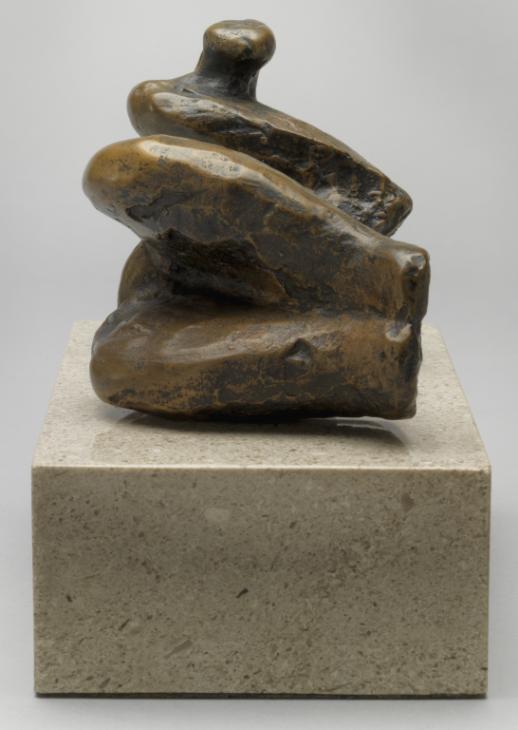

Reclining Figure: Bunched is a small preparatory study for larger sculpture that was ultimately made from marble. It presents a distorted human body lying on its side in an apparently twisted position, the dynamism of which was associated by the critic David Sylvester with the work of Michelangelo.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Reclining Figure: Bunched

1961, cast 1961–2

Bronze on a Hoptonwood limestone base

130 x 166 x 93 mm

Presented by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler 1974, accessioned 1994

Number 9 in an edition of 9 plus 1 artist’s copy

T06826

Reclining Figure: Bunched

1961, cast 1961–2

Bronze on a Hoptonwood limestone base

130 x 166 x 93 mm

Presented by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler 1974, accessioned 1994

Number 9 in an edition of 9 plus 1 artist’s copy

T06826

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler in 1962, by whom presented to Tate in 1974, accessioned 1994.

Exhibition history

2004–5

Cubism and its Legacy: The Gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, Tate Modern, London, May–November 2004; Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, December 2004–May 2005, no.42.

2008–9

Heimo Zobernig and the Tate Collection, Tate St Ives, St Ives, October 2008–January 2009, no number.

References

1962

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, M. Knoedler and Co., New York 1962 (another cast reproduced p.53).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.7 (?another cast reproduced fig.13).

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977 (plaster original reproduced p.110).

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, no.489 (?another cast reproduced p.51).

1994

Tate Gallery Biennial Report 1992–94, London 1994, p.57.

2000

Moore in China, exhibition catalogue, Beihai Park, Beijing 2000 (plaster original reproduced p.57).

2004

Giorgia Bottinelli, ‘Henry Moore’, in Jennifer Mundy (ed.), Cubism and its Legacy: The Gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2004, pp.82–7, reproduced p.85.

2009

Heimo Zobernig and the Tate Collection / Heimo Zobernig and the Collection of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Modern Art Centre, exhibition catalogue, Tate St Ives, St Ives 2009, reproduced p.54.

Technique and condition

This is a small bronze sculpture of a reclining figure mounted on a thick rectangular base made from polished Hoptonwood limestone. Henry Moore probably made the original model for this sculpture from wax. The surface is freely modelled with a texture that suggests he used a hot spatula or soldering iron to soften and move the wax around. High points such as the chest and legs seem to have been intentionally melted to produce a smooth surface finish. This wax model was then cast in plaster, which is a more durable material, from which a mould would have been taken to be used to cast the sculpture in bronze. The size of this bronze and the level of detail on its surface suggest that it was cast using the traditional lost wax technique. Small file marks show where casting seams and flashes have been chased from the finished bronze, but there is otherwise little evidence of post-cast finishing.

The artist’s signature and edition number, ‘Moore 9/9’, are inscribed on the sole of the figure’s left foot (fig.1). The raised edges of this inscription indicate that it was made with a sharp point in a soft material, probably wax, before casting. Although the sculpture is not stamped with a foundry mark, records held at the Henry Moore Foundation confirm that the sculpture was cast at the R. Fiorini & J. Carney Foundry, London, in an edition of nine plus one artist’s copy.

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961–2

Tate T06826

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961–2

Tate T06826

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Underside of base of Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961–2

Tate T06826

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Underside of base of Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961–2

Tate T06826

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The surface has been artificially patinated, which means that chemical solutions were applied to the surface that reacted with the bronze to produce coloured compounds. First, a layer of opaque dark brown patina was applied, probably using a solution of potassium polysulphide (known in foundries as ‘liver of sulphur’). This was then rubbed back on the high points with a light abrasive, exposing the original colour of the cast bronze. A second, transparent and lighter brown layer of patina, which is often achieved using a more dilute solution of the same chemical, was then applied across the surface. The bronze was finally coated in a layer of protective wax.

The underside of the base is covered with grey felt but it is possible to see two depressions through it where the fixings, which are likely to be screws or bolts, enter the limestone (fig.2).

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961–2 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, April 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Reclining Figure: Bunched is a small bronze sculpture of a distorted human figure reclining on a Hoptonwood limestone base. It was made in 1961 and served as the preliminary model for a larger sculpture originally carved in Travertine marble and later cast in bronze.

The human form of this figure has been abbreviated to such an extent that certain features appear to melt into each other. Nonetheless, the overall shape of the bronze appears to present a figure lying on its side, identified by the position of two bent legs, which are the most recognisable human features. At the other end of the sculpture the various bulbous and projecting forms are suggestive of arms, shoulders, breasts and presumably a head (fig.1). The subtitle of this work, ‘bunched’, is a vivid description of how Moore has modelled the forms of this figure, as though the limbs are conjoined together. For example, the appendage that curves over the body at the top of the sculpture to create a hole might represent a raised right arm supporting a small misshapen head.

The torso is made up of depressions and protrusions, and appears to be twisted so that the arms and head face backwards while the knees face forwards (fig.2). The legs and feet are fused together and although the knees are parted, only a small crevice separates them. The feet hover above the base and have flat soles on which Moore has inscribed his signature and the edition number.

Making Reclining Figure: Bunched

By the time Moore created Reclining Figure: Bunched in 1961 he rarely made preparatory drawings for his sculptures. Instead he preferred to test his designs in three dimensions by making small maquettes out of clay, wax or other malleable materials. However, a drawing by Moore dated 1960 depicts a reclining figure that, with its pierced or split head, recessed stomach and voluminous bent knees, closely resembles Reclining Figure: Bunched (fig.3). The drawing’s high level of finish suggests that it might be a mis-dated study of the finished sculpture, however it is also possible that Moore, having made numerous drawings for reclining figures throughout the 1950s, had a already conceived the design of the sculpture by 1960.

Henry Moore

Figure in Setting 1960

Charcoal, pastel and watercolour wash on paper

362 x 572 mm

The Henry Moore Family Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Figure in Setting 1960

The Henry Moore Family Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

In 1960 Moore stated, ‘I make most of my sculptures direct in plaster – if they are going to be in bronze’.1 A plaster maquette for Reclining Figure: Bunched (fig.4) in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation testifies to the working method described by Moore, but the surfaces of the bronze version suggest that this plaster may have been created from a maquette made of wax. The smooth surface texture of the torso could have been achieved by dipping wax into hot water, or by melting it with a heated spatula. The sharp edges on the rear of the sculpture, in particular on the calves and back, also look as though they were made by cutting into wax (fig.5). The plaster maquette would have been made by casting the wax version in plaster so as to create an exact replica of the design. Plaster is a more durable material and this second maquette would have been the one used to create a mould from which the bronze cast could be made. The plaster maquette was also used when the sculpture was enlarged in marble and bronze; its surfaces are marked in pencil with a number of ‘x’ shapes indicating that it was used as the template for a scaled-up version.

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961

Plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961–2 (rear angle view)

Tate T06826

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961–2 (rear angle view)

Tate T06826

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

When it was finished Moore sent the plaster maquette to the R. Fiorini & J. Carney Foundry in London to be cast in bronze. At the foundry the sculpture was cast using the lost wax technique, which involved making a mould into which molten wax was poured. Once the wax had hardened it could be released from the mould, forming an exact replica of the sculpture. It was at this point that Moore’s signature and the edition number were inscribed into the feet of the figure. The wax model would then be encased in a hard refractory material, placed in a kiln and heated until it melted. Channels within the casing would allow the wax to drain away and, once empty, the cavity was filled with molten bronze. Once the bronze had hardened its casing was removed, revealing the cast sculpture. Small tool marks on the surface of the bronze indicate where casting seams were filed down. Reclining Figure: Bunched was cast in an edition of nine plus one artist’s cast, all of which were made between October 1961 and June 1962. As it is the ninth cast of the edition, Tate’s sculpture was probably one of the last to be produced.

After it was cast the bronze sculpture was returned to Moore so that he could inspect the quality of the casting and make decisions about patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the bronze surface. Reclining Figure: Bunched has a dark brown patina which in certain areas has been rubbed back to expose the original colour of the cast bronze. A layer of wax was then applied to protect its surface.

At just over 13 cm high and 16 cm long, Reclining Figure: Bunched was intended to serve as a preliminary model for a larger sculpture. In 1969 Moore completed the large travertine marble version of the sculpture, which reproduces the roughly modelled surface texture of the small bronze. The large bronze version of Reclining Figure: Bunched was cast in 1985 at the Morris Singer Foundry in Basingstoke.

Moore and the reclining figure

Moore carved his first reclining figure around 1924 but took up the subject with greater seriousness in 1929 and it became his most frequently recurring subject. In 1947 Moore accounted for his preference for the reclining figure, stating:

There are three fundamental poses of the human figure. One is standing, the other is seated, and the third is lying down ... of the three poses, the reclining figure gives most freedom compositionally and spatially. The seated figure has to have something to sit on. You can’t free it from its pedestal. A reclining figure can recline on any surface. It is free and stable at the same time. It fits in with my belief that sculpture should be permanent, should last for eternity. Also, it has repose, it suits me – if you know what I mean.2

Moore also believed that because the subject of the reclining figure was known and understood, he was not tied to creating naturalistic or representational artworks. On the subject of his reclining figures Moore was clear that he did not seek to imbue his sculptures with a specific meaning, but rather to use the motif as a starting-point for formal experiments:

I want to be quite free of having to find a ‘reason’ for doing the Reclining Figures, and freer still of having to find a ‘meaning’ for them. The vital thing for an artist is to have a subject that allows [him] to try out all kinds of formal ideas – things that he doesn’t yet know about for certain but wants to experiment with, as Cézanne did in this ‘Bathers’ series. In my case the reclining figure provides chances of that sort. The subject-matter is given. It’s settled for you, and you know it and like it, so that within it, within the subject that you’ve done a dozen times before, you are free to invent a completely new form-idea.3

Reclining Figure: Bunched may be understood as a development of Moore’s earlier Reclining Figure 1929 (fig.6), which was carved in brown Hornton stone and presents a female figure lying on her right side with bent knees and one arm raised to her head. Reclining Figure: Bunched not only echoes the pose of the earlier sculpture but presents the body as a series of ‘bunched’ or compressed masses, emphasising its weight and spatial presence in a way that is comparable to the block-like composition of the 1929 sculpture. However, a comparison between these works also highlights the way in which Moore gradually took ‘steps away from realistic representation’, stretching the boundaries of his sculptural vocabulary while simultaneously maintaining a commitment to the figurative form.4

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1929

Brown Hornton stone

Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1929

Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Michelangelo's Conversion of Saint Paul c.1542–5

Pauline Chapel, Vatican City

Fig.7

Detail of Michelangelo's Conversion of Saint Paul c.1542–5

Pauline Chapel, Vatican City

The origins of Moore’s fascination with the subject of the reclining figure cannot be attributed to a single definitive source. For example, in the catalogue to Moore’s 1968 exhibition at the Tate Gallery, images of a reclining Chacmool, a rain spirit of the ancient Toltec-Mayan culture, were reproduced alongside Michelangelo’s carvings of allegorical figures in the Medici Chapel in Florence under the title ‘comparative material’. While the author of the catalogue, the critic David Sylvester, suggested that Michelangelo’s work had a greater bearing on Moore’s more naturalistic reclining figures from the late 1920s and early 1930s, he also argued that Moore’s more abstract sculptures evoked ‘poses which are the perogative of the Mediterranean tradition’.5 By way of an example, Sylvester noted that Reclining Figure: Bunched had ‘a remarkable resemblance to the stricken St Paul in the Pauline Chapel fresco of the Conversion’ (fig.7).6 It is possible that Sylvester not only saw similarities in the poses of the two figures, but also in their taut, twisting musculature and sense of compressed energy.

The Kahnweiler Gift

Reclining Figure: Bunched was presented to Tate by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler.7 In the 1950s and 1960s the Kahnweilers were among the few art collectors in the United Kingdom who actively supported the work of European modern artists and they amassed a large collection of paintings and sculptures by artists including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Fernand Léger. Partly as a result of their friendship with the Tate director Sir John Rothenstein and with his successor Sir Norman Reid they decided to leave their entire art collection to the gallery after their deaths. A Trust Deed was signed in 1974, immediately after which a group of works were passed over to Tate. Gustav died in 1989 and the remaining works, including Reclining Figure: Bunched, were accessioned into the Tate’s collection in 1994 following Elly’s death in 1991.

It is not known how or when the Kahnweilers first met Henry Moore, but they may have become familiar with his work in the late 1930s when Moore exhibited at the Mayor Gallery in London, one of the few commercial galleries that actively exhibited and supported the work of modern artists working in Britain and continental Europe. Nonetheless, by the 1950s the Kahnweilers, Moore and Moore’s wife Irina shared a warm friendship. As well as purchasing works by Moore for their own collection, Gustav acted occasionally as an agent in the sale of Moore’s sculptures. For example, in 1952 he negotiated the sale of Moore’s sculpture to the Kunstmuseum in Basel. The Kahnweilers acquired Reclining Figure: Bunched directly from Moore shortly after it was cast. Moore’s sales log book records that the sculpture was collected by Kahnweiler on 26 July 1962, and it remained in their home in Buckinghamshire, where the couple moved from Cambridge in 1956, until it entered the Tate’s collection.8

Before he died Gustav left detailed instructions regarding the Tate’s gift, and following Elly’s death a total of fifty-five artworks entered the Tate’s collection, including works by Georges Braque, Paul Klee, Henri Laurens, André Masson and Picasso. Along with Reclining Figure: Bunched, four other sculptures by Henry Moore were included in the Kahnweiler Gift: Maquette for Standing Figure 1950 (Tate T06827), Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956 (Tate T06824), Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956 (Tate T06828), and Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (Tate T06825).

Alice Correia

April 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.233.

Henry Moore cited in J.D. Morse, ‘Henry Moore Comes to America’, Magazine of Art, vol.40, no.3, March 1947, pp.97–101, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.264.

Henry Moore cited in Arnold Haskell, ‘On Carving’, New English Weekly, 5 May 1932, pp.65–6, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.190.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and the Values of Business Alex J. Taylor

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961, cast 1961–2 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, April 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www