Henry Moore and the Welfare State

Dawn Pereira

Inspired by his experiences as a war artist, Henry Moore wanted to help build a ‘better Britain’ in the 1940s and 1950s, siting his monumental bronzes amid new housing developments and social spaces. This essay traces Moore’s engagement with the ideals and commissioning processes of the welfare state in the post-war years.

Sometimes without knowing why – people all over the world can see that his sculpture has a quality that is relevant to themselves.

Alan Bowness 19651

Alan Bowness 19651

Moore's Draped Seated Woman 1957–8 at the Stifford Estate in 1962

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Moore's Draped Seated Woman 1957–8 at the Stifford Estate in 1962

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Although Moore’ sculptural work has been written about extensively, his relationship with the British people and their everyday environments has not been fully explored. In New Art, New World: British Art in Postwar Society (1998) Margaret Garlake discussed how Moore’s sculptures were taken as a ‘prototype for a new kind of public art for the post-war world; one that would complement the reconstructed cities and most importantly, proclaim the values of the New Britain’.5 Yet, as art historian Andrew Causey pointed out in 2010, there is also a difficulty in seeing Moore fully as an urban artist, ‘not only because of the ways he used natural materials and how his sculptures frequently referred to landscape, but also because he was only intermittently concerned with the disruptions and discontinuities of urban life’.6

Moore took pride in remaining an ‘ordinary man’, wanting his work to be used socially and seen by a wider public. But how did his sculptures become seen as expressing the ideals of the welfare state? How was someone unversed in modernist art expected to find commonality with Moore’s increasingly personal and abstract subject matter? And why were his works understood at the time to transcend somehow the limitations of education and class, region and period?

Moore’s attitude to the welfare state

In 1933 Henry Moore became a member of the Unit One group of architects and artists and joined the Artists International Association (AIA), which aimed to use art as a weapon in the class struggle.7 Brought up in a working class mining background, the son of a committed socialist, Moore was happy to describe his political views in response to a Unit One questionnaire as leaning to the far left: ‘My greatest sympathies lie towards communism. I imagine every decent (moral, intelligent) person nowadays is more socialist than anything else.’8

At AIA’s first exhibition The Social Scene, held in London in 1934, the artists presented a manifesto that stated: ‘Today, when the Capitalist system and Socialists are fighting for world survival, we feel that the place of the artist is at the side of the working class.’9 Against the backdrop of worsening political tensions abroad, the Association came more and more explicitly to oppose fascism and to see the threat of war and the suppression of culture as interlinked. Moore joined the selection committee for the AIA exhibition Art for the People, held at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1939.10 Fearing that the public had lost its curiosity about contemporary art, the Association arranged for the show to be opened by a ‘MAN IN THE STREET’11 – an unemployed labourer who duly declared it ‘a wonderful success’.12 Through the AIA Moore also became involved with a publication that attacked the British government’s policy of non-intervention in the Spanish Civil War. He also signed letters to drum up support for the British section of the International Peace Campaign and raised funds as a member of the Artists Refugee Committee. However, when the nationalist regime refused him a permit to visit Spain at the invitation of the republican party, Moore did not try to enter illicitly, unlike the poet Stephen Spender who recalled: ‘Henry always took the line, very sensibly I think, that his art expressed his feelings and was therefore in some mysterious way anti-fascist and humanistic.’13

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Tube Shelter Perspective 1941

Graphite, ink, wax and watercolour on paper

support: 483 x 438 mm

Tate N05709

Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee 1946

Fig.2

Henry Moore OM, CH

Tube Shelter Perspective 1941

Tate N05709

Moore’s drawings of tube shelterers and miners were quickly seen as symbolising British resistance to the Blitz. Read describing them as the ‘most authentic expression of the special tragedy of war – its direct impact on the ordinary mass of humanity, the women, children and old men of our cities.’17 It is unlikely, however, that working class people saw much of Moore’s images of them during the war. Some drawings by war artists were exhibited at the National Gallery during 1941, though a study of the age, social status and sex of visitors showed that the majority was perceived to be Social Class B, or middle class.18 The work of war artists was also publicised through the 1943 film Out of Chaos, written and directed by Jill Craigie, which may have attracted a wider audience. Craigie later recalled Moore’s ideals in this era: ‘One of the great things about the war was the breaking down of the class barriers and Henry was all part of this spirit.’19 She also observed that once Labour came to power in 1945 differences in class became apparent again, although the widespread desire to build a ‘better Britain’ remained strong.

The role of war artist had shown Moore a way to connect with the ordinary man. ‘I think I would have been a far less sensitive and responsible person – if I had ignored all that and went on working as before. The war brought out and encouraged the humanist side in one’s work’, he later said.20 The challenge for Moore, however, remained to find a way to achieve the same emotional resonance with people through his sculptures.

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943–4

Hornton Stone

Church of St Matthew, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943–4

Church of St Matthew, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

It is wrong to assume that the church-going public will dislike contemporary art in a church. Surely, it is true that good art appeals at all levels and great art appeals in all ages and conditions and if the greatest art of all periods and the best art of each era should not be in the churches, where should it be?23

Asking as many local people as he could about the sculpture, McLean found that they all knew about the artwork. A taxi driver thought it was good for trade as people came to view the sculpture from further afield, but a ticket collector responded, ‘I never go to church and if I did I would not go to see that rubbish.’24 A waitress said she was drawn to revisit the work, going back to the church every week to look at the Madonna and Child. Although Clark had completely misjudged his audience in one sense, he had predicted in his speech that the congregation would sense more and more each day the work’s harmony and tenderness of feeling.

In the same year that Moore’s church commission was initiated the development of a ‘welfare state’ was being discussed in a committee chaired by economist and leading civil servant Sir William Beveridge. In a report published in December 1942, he set out proposals against the ‘five giant evils’ of want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness, and spoke of the state providing security for people from the ‘cradle to the grave’.25 The Manchester Guardian felt that the report not only welded into an administrative unity ‘our splendid but untidy and wasteful social services, but [also charted] a great piece of national reconstruction.’26 In 1945 Labour’s election campaign slogan ‘Let Us Face the Future’ captured the nation’s appetite for change and positioned the party as the one best placed to rebuild Britain after the war. Coming into force in 1947, the 1944 Education Act provided free secondary education for all pupils up to the age of fifteen, aiming to widen the opportunities available to children from all backgrounds. The aspiration to provide affordable separate dwellings for every family led in 1947 to the Town and Country Planning Act. In 1948 the National Health Service was introduced, making medical and allied services available and free to all.

Yet, if public art was to become an accepted part of this newly developed post-war state infrastructure, as Moore had envisaged in his ‘better Britain’, there were still barriers to overcome. In 1946 artist and writer Cora Gordon claimed that ordinary people had a craving for spiritual and intellectual but they were not equipped to appreciate modern art:

Art still remains a puzzle to the many bewildered folk who have been encouraged to record and applaud the imitations of prettiness as ‘Truth’. As they learned at school that ‘Truth is Beauty’ and they didn’t also learn what Truth implied, they are now left to dispose of all their distaste for the old and the modern masters by the caustic remark ‘I suppose I’m not educated up to this’. Now, however, a growing public is dropping cheap sarcasm for a definite desire to educate itself up.27

After the war various steps had been made to educate the public. The Society for Education through Art (SEA), for example, sponsored an annual ‘Pictures for Schools’ exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum from 1947 onwards. Such books as Arthur T. Broadbent’s Sculpture Today in Great Britain (1944) had claimed it was no longer a rarity for people of more moderate means to commission art and buy sculpture to adorn their homes and from 1945 to 1959 the Sculpture in the Home touring exhibitions offered post-war homemakers throughout Britain the opportunity to buy work by renowned artists, including Moore.28 By the 1950s newspapers, magazines, radio and television increasingly brought modern art into mainstream culture but it was still widely felt that after a hard day’s work the working man preferred relaxation to education. ‘The majority don’t want art. They want distraction’, the left-wing critic John Berger wrote in 1955. ‘You may not like it but art is the prerogative of the few’.29

Family Group 1948–9 installed at Barclay School, Stevenage

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Furze, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Family Group 1948–9 installed at Barclay School, Stevenage

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Furze, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore designed Family Group with children very much in mind: the arms of the mother, father and child linked to create a physical bond that suggested tenderness, protection and stability. The work, however, was given a poor reception at the school when first installed. In an article titled ‘”Belsen” Statue Came in the Night’ the Daily Dispatch recorded local reaction as a mixture of negativity, confusion and anger, owing in part to people not having been consulted or warned about the sculpture’s arrival. Moore’s sculpture was described as ‘unreal’, ‘ugly’ and ‘not art’; there were even concerns that rotten eggs might be thrown at it during the unveiling ceremony. One girl pupil aged twelve was quoted as saying, ‘It does not look like any human being I have ever seen. I could do better myself.’ The local postman described himself as ‘shocked’ when he first saw the sculpture while delivering the post: ‘I looked and almost let the letters I was carrying drop from my hands ... “They tell me it needs a lot of appreciation – I bet it does.”’ The loyal headmaster, however, was recorded as liking the work, noting how students enjoyed walking up to it and touching it.32 Conservative commentators joined in. Responding to Moore’s Family Group in 1950, the painter Sir Alfred Munnings – a traditionalist and outspoken critic of modernist art – said: ‘Distorted figures and knobs instead of heads get a man talked about these foolish days. Anyone can do round balls for heads. Few can chisel the features of a face.’33 When asked in an interview who was to be the judge of what constituted good art, Munnings replied, ‘the man in the street.’34

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 installed on the South Bank during the Festival of Britain 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 installed on the South Bank during the Festival of Britain 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Significantly, Reclining Figure featured in John Read’s BBC film Henry Moore: Art is the Expression of Imagination and Not the Imitation of Life, broadcast in 1951. The film introduced a television-viewing audience (although fewer than one in twenty households had a television set) to Moore’s methods. Sculpture was shown to emerge from ideas in a notebook and then be developed through detailed drawings, maquettes, full-size plaster models and finally bronze casts, which were assembled at a foundry after six months of ‘intensive labour’. Film historian John Wyver has noted that the overall tone of the film was ‘defensive’: it was assumed that viewers would be resistant to the artist’s abstract forms and constantly emphasised the historical precedents for Moore’s work.39 But it also shared with the viewer Moore’s own delight in seeing his works in the round. Read later recalled, ‘Nothing has pleased Moore as much as seeing his sculptures revolving on turntables before the lens, or continuously revealing their perspectives as the camera glides past or moves into his work’, and positioned Reclining Figure and the camera on the same rotating platform. 40

Public commissions

As the components of the Welfare State gradually creaked and clanked into position the accompanying architecture began to arise. It was far from spectacular but it contained an amount of young and vigorous thought and in two fields especially – school-building and housing – it was soon discovered that a really triumphant advance has been achieved.

Trevor Dannant 195941

Trevor Dannant 195941

Through his frequent appearances in television programmes Moore entered the homes of a broad public across the nation in the 1950s but it would be the LCC’s regeneration of the capital that would provide him with more direct ways of connecting with the ‘man in the street’ through public commissions by a state-funded body. In 1948 the Local Government Act had permitted local authorities to provide financial support to drama, music, entertainment and other cultural endeavours and from then until 1965 approximately four-fifths of the financial support local authorities provided to the entertainment arts and the visual fine arts were distributed through the Arts Council, the remainder being dispersed through regional education authorities and local housing councils.42

Henry Moore's Harlow Family Group 1954–5 outside St Mary of Latton Church, Harlow

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Henry Moore's Harlow Family Group 1954–5 outside St Mary of Latton Church, Harlow

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

London’s post-war redevelopment was the subject of the plan for the County of London, commissioned in 1941 and drawn up by Sir Patrick Abercrombie, Professor of Town Planning at London University and J. H. Forshaw, Architect to the Council. This plan envisaged new separate community areas, subdivided into neighbourhoods of 6,000 to 10,000 people, with each of these mixed developments centred on a school and group of local shops. It was acknowledged that it was going to be difficult psychologically for people who had suffered so much during the war to accept these replacements for familiar streets and networks, and it was hoped that public art could play a role in reinstating a sense of community through symbolic and aesthetic means. The LCC, however, had to address the challenge of creating a balance between artworks with which the public could identify with and the ‘high art’ promoted by an elite.

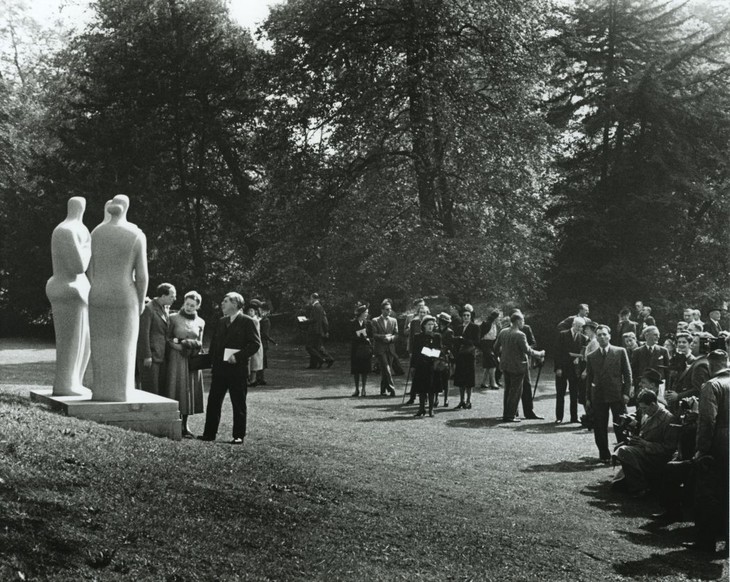

Henry Moore's Three Standing Figures 1947 in the Open-Air Sculpture Exhibition at Battersea Park, London 1948

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore's Three Standing Figures 1947 in the Open-Air Sculpture Exhibition at Battersea Park, London 1948

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

By 1956 the reconstruction of London was well underway and the changing financial climate made it possible for the LCC to set aside £20,000 annually to commission or purchase works through its Patronage of the Arts Scheme. The Labour-led Council wanted to show that it could inspire social renewal and create memorable new and redeveloped environments, while the Conservative government was keen to restructure the administration of the capital to regain greater control of the city and its suburbs. For the Chairman of the LCC, Isaac Hayward, himself a working class man, the challenge of reconstructing London was not merely an issue ‘of bricks and mortar but of flesh and blood, of the personality, customs, hopes, aspirations and human rights of each individual man, woman and child who needs a home.’50

Although the LCC was keen to break new ground in the arts, the implementation of the Patronage of the Arts Scheme was complicated by differences of opinion among LCC members about the choice of art.51 It was also difficult to reconcile the tastes and wishes of the members’ constituents with the advice given by the Arts Council advisory sub-committee, which wanted to promote high aesthetic quality. Arts Council representatives began to push for the purchase of relatively expensive work by established artists and those considered too avant-garde by many of the LCC committee members. LCC architect Kenneth Campbell recalled:

They were not always keen about recommending very young artists and seemed to feel they were there to promote good art and wanted some of it to be by good older modern masters, such as Moore and Hepworth. This sometimes clashed with LCC policy because part of our basic concept was to provide patronage for young talent not already receiving acceptance and patronage.52

In May 1959 Gabriel White, a new Director of Art at the Arts Council, proposed the acquisition of the last example in the edition of Moore’s Fallen Warrior 195653 for the Portsmouth Road section of Alton Estate in Roehampton. It was presented to the LCC as an ideal opportunity to acquire a work by Henry Moore.54 Moore himself, however, rejected the idea of siting the work in a new housing development, saying he felt the site was ‘inappropriate’. His Warrior with Shield 1953–4 from the same series had been used as a war memorial at Arnhem, and he may well have felt it odd for people on a housing estate to be confronted with a work depicting pain, even if stoically borne.

In the early 1960s Moore was at an age when people usually retired and yet he was more prolific than ever. His casting of bronze works in editions allowed him to reach more audiences as well as build a sizeable fortune, and responded in part to the desire of commissioning bodies that wanted him to make ‘the same again, only more so’.55 In 1961 the LCC formed the Advisory Body on Art Acquisition and approached Moore again, hoping the selection of his work would defuse tensions between LCC and Arts Council members and bring prestige to the Patronage of the Arts Scheme. On this occasion a commission was sought for Stifford Estate, Stepney, and a sum of £2,200 was set aside to pay for a major work in what was deemed an area of ‘prominence and importance’.56 In July 1961 Moore’s bronze Draped Seated Woman 1957–8 was suggested at a cost of £7,000 (including patination, the base, transportation and installation). Arts Council members urged the LCC to buy the work, described as the ‘last remaining copy of the sculpture available, with no others in London’.57

Not all LCC architects, however, were happy with this approach. In the first year of the Patronage of the Arts Scheme the Housing Division’s ‘Research and Development Group’, led by architect Oliver Cox, decided that it did not fulfil their artistic vision for housing estates. Cox recalled, ‘In 1957, I got a little bit fed up with the procedure that the Arts Council were doing, which, I called ‘dumping’. They were very fine works of art on estates but without any relationship to the architects who were working there.’58 The Design Consultant Scheme was different in that the artworks were often made on site in direct response to the environment, with artists collaborating with architects and construction teams while the building took place.

Two Royal College of Art graduates, Antony Hollaway and William Mitchell, were chosen for the role and produced site-specific thematic and decorative artworks in the form of murals and some freestanding pieces. The Consultants’ form of art related to popular culture rather than an elite art and seemed more obviously in tune with the ideals of the Welfare State, with both wanting to create something suitable for the residents, reflect their own ideas and those of the architects, and put their specialist training to good use in the community.59 Moore became aware of the Consultants in his role as an Arts Council representative, visiting their exhibition at the LCC’s County Hall headquarters in 1959. Moore had been interested in what they were doing, particularly Mitchell’s design for vacuum-formed PVC mould liners to be used to create concrete cladding made of slabs that could be combined in various permutations.60 The cladding could be used as low relief decoration when placed over a large area. Cox recalled: ‘we had maquettes, big scale; a whole end wall of a block.’61

Stifford Estate had been erected on a site of some nine acres. The mixed development consisted of three seventeen-storey blocks within a newly laid park, five four-storey blocks and a terrace of six houses. During construction Hollaway created a series of artworks for the seventeen-storey Swedish-inspired point-blocks. Constructed around a central core for services, these towers housed mosaic murals on lift hall walls and staircases.62 Concrete murals designed for the external entrance halls formed part of the load-bearing walls and were cast from patterned polystyrene shutter linings during the building process, with Hollaway confidently drawing the designs freehand using a soldering iron (a technique he described as ‘free drawing in relief concrete’).63 One of these murals featured in a scene of the British film Sparrows Can’t Sing, filmed in 1962, based on working class life in post-war East London. The film showed a male character resting his bicycle up against Hollaway’s abstract artwork and a caretaker saying to him: ‘Hey, don’t lean that against the hieroglyphics mate, ain’t you got no taste?’64 The comment satirised a working class response to art and again raised the issue of how relevant contemporary art was, particularly in areas previously known for educational and social deprivation.

Henry Moore's Draped Seated Woman 1957–8 being installed in the Stifford Estate, Tower Hamlets, London in 1962

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore's Draped Seated Woman 1957–8 being installed in the Stifford Estate, Tower Hamlets, London in 1962

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In the early 1960s, with new housing and schools being built, the LCC turned its attention to tertiary education, planning to build further education colleges with the substantial artworks thought necessary for these large prestigious sites. In 1963 the Robbins Report had recommended that schools, local authorities and universities co-operated to ensure that further education was made available to all who were qualified by ability and attainment. This was a continuation of the work that had been initiated after the war, where government schemes supported people from the armed forces from a variety of social backgrounds back into education. In May 1963 the LCC’s Advisory Body began to discuss a potential artwork for the new Chelsea School of Art, the first post-war building that the Council had designed specifically for art education. As Moore had been Chelsea’s first Head of Sculpture from 1932 to 1939, he was seen by the College as the ideal choice for the commission. It was also thought that the Arts Council’s notion of ‘seeing before buying’ would ensure the piece’s suitability, reducing the risk of potential problems.

The School’s Advisory Committee at the Chelsea School of Art wrote to the LCC proposing that it purchase an eleven to twelve feet reclining figure that Moore was working on at the time, offered at a cost of £7,500. A follow-up report by the LCC stated that the Chelsea’s Principal Lawrence Gowing had noted that the price was ‘probably less than three quarters that which the work could command in the ordinary way on the art market’ and emphasised how much the sculpture ‘would mean to London and to the school.’69 Two Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1959 was sited in an internal courtyard in March 1964 and later lent to Moore’s first major retrospective exhibition, held at the Tate Gallery in 1968.

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3, Brandon Estate, original position with view showing buildings in background, tall plinth

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3, Brandon Estate, original position with view showing buildings in background, tall plinth

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

As a member of the Advisory Body, Hollamby visited Moore at his Hoglands home to discuss the acquisition of a reclining figure. Hollamby then had to secure the support of the Housing Committee. He later recalled an ‘electrifying’ meeting, conducted at the time of the Cuban missile crisis, in which the members were moved by his emotional speech about what ‘Henry Moore’ stood for and what this sculpture could mean, at a time when the world was facing such terrible possibilities.72 Support secured, he began working on preparing the site for the sculpture in December 1962 and liaising directly with Moore on the designs, both trying out ideas on the architect’s drawing board until they ‘got it right’ (Hollamby subsequently regretted that he threw Moore’s sketches in the bin).

The Brandon Estate offered a bold mix of different types of art. For his part, however, Hollaway resented that his body of work was made for a fraction of the money spent on acquiring works, particularly the Moore, through the Patronage of the Arts Scheme.73

Initial responses

At Harlow New Town it had been thought that the young families, many arriving from north London, would identify with Moore’s Family Group. Yet, situated in an isolated location on an open grassy slope, selected by the artist so it could be seen from a distance, it was vulnerable to petty vandalism (the stone was chipped by missiles, a figure was dressed with a tea cosy and the heads were given green whiskers). Even when moved to a new location, the sculpture was subject to abuse, culminating in a brick being thrown by a thirteen-year-old boy, breaking off the carved child’s head in 1963. The sculpture was returned to Moore for him to see the extent of the damage and decide on the work’s future.74 Although this ‘humanitarian’75 artwork had been made for the people, it was eventually decided to place the sculpture on a high pedestal for its protection in the town’s central square where vandals would be more easily seen and deterred.

On the BBC’s ‘Face to Face’ programme, broadcast in 1960, a former politician John Freeman asked Moore whether modern artists like him were out of touch with the popular mood and if their sort of work was a form of escapism or an expression of despair or of some secret joy of their own. Moore replied that he was never worried much about the communication between the artist and the public. He acknowledged that he did not expect someone who had not been to the British Museum or seen a real piece of sculpture to immediately understand what he was trying to do, but this connection, he said, would ‘come about through more chance of the average public to see sculpture.’ 76 Moore had hoped that accessibility would endear his work to the people and did not want to comment, in public at least, when popular response was negative. About vandalism he would say it was ‘just the work of silly hooligans, just silly people and often it is better no fuss is made of it.’77

When American art historian Dolores Mitchell interviewed Moore at his home, in the late 1960s, she had been struck by how important it was to him as a sculptor, to contribute to the rebuilding of Britain after the Second World War. She recalled: ‘While I sensed he had come to prefer unrestricted creativity, he continued to accept public commissions and collaborations willingly. Moore retained the social idealism present in the Festival of Britain and promoted by the Labour Government’.78 Moore had now lived in his house in Perry Green for over thirty years and little had changed in the way he conducted his life. But he now moved away from creating site-specific works, and instead encouraged patrons, architects and developers to visit his studio and discuss possible acquisitions from among already completed pieces. When Mitchell asked Moore about his public commissions and how he made decisions about the placement and materials to be used, the artist said that he believed that sculpture needed to be either in total contrast or in harmony with a site, and that it should always be possible to walk around it and contemplate it within its setting. The architect was responsible for ensuring the ‘human content’ and appeal of the space and needed to be part of this decision-making process.79

The placement of Moore’s sculptures was explored further in David Finn’s glossy book Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment (1977). The idea for the volume had arisen from a conversation between the Moore and Finn, a collector and the author, when they had discussed how various casts of the same sculpture could produce different experiences depending on how and where they had been placed.80 Finn visited a number of publicly sited sculptures by Moore, analysed their function and photographed them in situ.81

Finn’s first impression of Moore’s Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 at Brandon Estate had been that the high pedestal kept the work beyond the reach of the viewer in what was a relatively lonely, barren site. In 1973 critic John Russell had noted that Moore’s two-piece reclining figures stood for the human body’s ability to survive and dominate, no matter how catastrophic their surroundings,82 and Finn attempted to convey this in his close-up shots of the Reclining Figure, claiming that it was ‘almost a match for the high-rise structures in the background’.83 He preferred, however, the setting of another example in a sculpture garden at the University of California, Los Angeles, where the work was placed near eye level, enabling viewers to engage with the work. With this piece, Finn was fascinated by the sense of being able to approach and look within the sculpture’s cave-like forms.

When Finn visited Two Piece Reclining Figure No.1 at the Chelsea School of Art, the sculpture had been moved to an open courtyard at the front of the building after its return from the Tate retrospective in 1968. Although Finn may have felt that the opportunity for the art students to have the artwork close by outweighed the drawbacks of its cityscape backdrop, former student and artist Steven Claydon recalled that it was regarded more ‘like an unwelcome uncle whose apparent intention it was to embarrass you in front of your friends’.84

On seeing Draped Seated Woman at Stifford Estate, Finn had felt shocked that such a remarkable and valuable work could be placed with so little apparent concern for its surroundings. Yet the LCC estates initially had been perceived as places to be proud of, with a good quality of life.85 This ideal was celebrated in the book Achievement: A Short History of the LCC (1965), in which it was pointed out that careful attention had been paid to providing ‘open, well planned and colourful estates, properly balanced visually and sociologically’.86 By 1971, however, the Guardian warned of the ‘taint’ attached to living in a council house or on huge uniform estates with their ‘whiff of welfare’ and of ‘second-class citizenship’.87

Although welfare spending by the Conservative Government remained stationary from the late 1970s, there were cuts in the amount given to housing and stricter eligibility rules for benefits. By the 1980s efforts were made to demunicipalise council housing with the ‘right to buy’ scheme, which encouraged tenants to purchase council property at a discount price. By the 1990s councils were encouraged to transfer their stock to housing associations or private landlords to be redeveloped or rebuilt. For the many disadvantaged and vulnerable people living on the run-down estates during this time of transition the reduction in government grants and funds available for maintenance led to their homes being perceived by some as ghettos. London estates like Brandon and Stifford were portrayed as bleak places to live. Tony Parker’s book The People of Providence’ (1983) tried to readdress the balance. From his experience of interviewing tenants and neighbourhood workers at Brandon Estate, Parker found that residents still felt a strong sense of community and it was thought that where the Patronage and Consultant artworks had been placed were the better parts of the estate to live. Yet the artworks of Hollaway, Mitchell and Moore were totally overlooked by the residents and people that worked on the estate, with art never being mentioned in the five-year dialogue. One neighbourhood worker commented:

Working-class people are not exactly kept away, but more kept separate from very many things that the middle class take for granted. I have in mind such things as further education, legal services, concepts such as taste and design and so on. Although I’m not suggesting that they are the essence of good taste necessarily, I’d choose Habitat as an example; the sort of basic good design, which they have is really not very apparent anywhere in a working class area such as this.88

In the Arts Council’s annual report ‘Value for Money’, published in 1979, a lack of educational access to culture was deemed to lie at the core of the problem: ‘The fact is although art potentially belongs to all men, it is often complex and demanding and actually belongs to those who have education and experience which equips them to enjoy it.’ The report argued that art should not be made less demanding and that subsidising great works of the past or difficult works by contemporary artists should not be dismissed as elitist as this would be condemning ‘the lock on the door to enrichment because you have failed to give people a key that fits it.’89

In 1989, Moore’s Family Group at Harlow again featured in the newspapers with another story of vandalism. The granite head of the child was pulled off and was saved only when an art student took the head and hid it in a cupboard. A tip off to the police secured its return amid nationwide publicity over the incident.90 Owing to continuing fears over its safety and new concerns over the weathering of the soft stone after its restoration, the sculpture was taken into the care of the Henry Moore Foundation until a way could be found to protect it in its original site. With towns and neighbourhoods failing to give their inhabitants the ‘key to the door’ of arts appreciation, or even discussing what it might constitute, modern sculpture continued to be vulnerable in public spaces.

Later responses

He longed as an egalitarian to be accepted by the masses and was prepared to put up with yobbish graffiti and philistine officials; how have they worn, these children of the Northampton Madonna?

George Melly 199391

George Melly 199391

In 1986 the local papers in Tower Hamlets celebrated the fact that Moore’s Draped Seated Woman on Stifford Estate had finally come into the possession of the local council, although the work then sat neglected, on a scruffy mound of grass, with no identifying plaque.92 The East London Advertiser pondered: ‘What do people think having art on their doorstep?’ With Moore’s sculpture used as a climbing frame and a target for bottle throwing, one local wit suggested, ‘I heard the bloke kicked its head in before [Moore] finished it.’93 It was reported, however, that tourists came in their droves and one appreciative eighty-year-old, whose home looked onto the green defended the piece, saying: ‘Whenever my relatives come from America they always want to see our statue.’94

In 1987 the sculpture was exhibited for six months at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park and then returned to the estate. Estimated by the East London Advertiser to be worth £250,000, Draped Seated Woman was ranked by one resident as ‘one of the world’s greatest sculptures’. Yet, another stated, ‘I can’t see the point of her but the kids liked climbing over it’ (this comment was supported by a photograph of two local girls snuggling into the lap of the bronze figure with the caption ‘Old Flo with new friends’).95 When the sculpture was taken to be cleaned by the Henry Moore Foundation in 1992, one tenant from Bradmore House commented, ‘I miss her; it was the only thing about this area that made the place seem nice.’96 In 1994 an East London Advertiser article, ‘Art in the Street’ reminded residents that they need not go to a gallery to see art. One tenant was reported as thinking ‘Old Flo’ amazing but that local people did not ‘appreciate’ her. In contrast, her husband considered that, ‘They should sell it and renovate the area.’97

Unlike the gleaming new architecture that had featured as a backdrop to the film Sparrows Can’t Sing in 1962, the Stifford Estate in the 1990s lacked the ‘human content’ and appeal that Moore demanded from his urban settings. This incongruity was noted in George Melly’s film J’Accuse: Henry Moore, broadcast on Channel Four in 1993. Here critic Sarah Kent condemned the decision to place art in housing estates: ‘In the 50s was a belief [that] if you plonked a sculpture in the middle of a spot like this that it somehow humanised this appalling urban environment.’98 While some critics continued to complain about the built environment and accompanying art of the 1950s and 1960s, conservationists took a different view. In 1998 the Department of Culture, Media and Sport and English Heritage listed nine artworks from the LCC’s Patronage programme, including Moore’s Two Piece Reclining Figure, No.3 at Brandon Estate, for preservation. Tony Banks, the Sports Minister at the Department of Culture, championed these artworks as he felt they enriched people’s experience of their local surroundings: ‘The works I am listing ... are all wonderful examples of art at its most accessible.’99

Moore’s Draped Seated Woman was not listed, although it had been recommended for this special measure, because it was moved once again ‘temporarily’ to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Taken ‘under the cover of darkness’, as it was reported, one estate resident, angry that the sculpture that he felt belonged to Stepney Green and had been on the estate for thirty years, might not be returned, said: ‘I kissed my first girlfriend there and the council have got no right to take it away. I’ve walked past that statue every day since I was knee high to a grasshopper.’100 In response the Council dismissed fears that the work, now reportedly worth £2.5 million pounds (according to the East London Advertiser), might be sold as ‘Chinese whispers’. But it emerged that, although the work was finally contributing to the enjoyment and identity of the local community, it no longer had a permanent home: the Stifford Estate was soon to be demolished to make way for new housing association homes.

Henry Moore's Draped Seated Woman 1957–8 at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park 2013

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jonty Wilde, courtesy the Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Fig.10

Henry Moore's Draped Seated Woman 1957–8 at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park 2013

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jonty Wilde, courtesy the Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Responding to the prominent art world advocates that championed retaining the piece in Stepney Green, critic Niru Ratnam claimed in the Spectator that councils should be able to sell public artworks that had lost their ‘relevance’: ‘It’s not only populations that change, taste does as well. Like all art, Moore’s work is of its time addressing generalised social themes that were congruent with the emerging post-war nation.’103 Ratnam questioned whether new inhabitants would want the return of Draped Seated Woman and whether it could still be assumed that ‘great’ artworks somehow transcended temporal and cultural differences. Moore himself did not live long enough to see the changes to the welfare state that focused on individual needs rather Beveridge’s ‘cradle to grave’ principle but the fate of works such Old Flo’ highlighted fundamental questions about the continued importance and relevance of his public sculptures and about how these might begin to be assessed.

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 Brandon Estate, Kennington, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 Brandon Estate, Kennington, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s LCC sculptures have proved to be among the most visible and long lasting of his efforts to create a ‘better Britain’. Their stories suggest that, if able to withstand acts of hostility, theft or violence, they can and do become a part of the character and history of a community over time. Although many Britons in the 1940s and 1950s were unversed in modernist art, Moore’s figures inspired in many, however slowly and grudgingly in some cases, an emotive response that helped win acceptance from local communities that had little investment in the arts. For others – and specifically for later generations – access to knowledge provided a key to acceptance. It is now over half a century since the works were installed in the new educational establishments, estates and towns of Britain’s post-war reconstruction and the passage of time has also helped wed the sculptures into the history of places: while the passage of a few decades made some feel the sculptures were dated or ‘irrelevant’, the sheer longevity of the pieces have allowed them to be seen by later generations as imbued with historical value. Moore himself always believed that his work needed time and contemplation to be fully appreciated, though even he might have been surprised by the cycle of changing responses evoked by his public works.106 Placed in the heart of people’s urban lives, these ‘welfare state’ sculptures allowed some, at least, to find in the massive bronzes qualities ‘relevant’ to themselves, as hoped by Moore and post-war urban planners. With the right forms of support (maintenance, physical protection and continuing education), they can contribute to what the artist termed the ‘human content’ of public spaces, representing, embodying and thereby preserving aspects of the social idealism that inspired the modern welfare state.107

Notes

Anon., ‘Mystery Figure’, Stepney Ahoy, August 1962, press cutting, Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives.

Peter Grant, ‘Art in the Street’, East London Advertiser, 1994, pp.10–11, press cutting, Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives.

LCC Principal Housing architect Kenneth Campbell suggested that ‘Moore was virtually donating’ the bronzes, which cost approximately £7,000 each. Dolores Mitchell, notes from interview with Kenneth Campbell, 3 November 1969, Dolores Mitchell collection of papers held by author.

Margaret Garlake, New Art/New World: British Art in Post-War Society, New Haven and London 1998, p.212.

Andrew Causey, ‘His Darkened Imagination: Henry Moore’, Tate Etc, no.18, Spring 2010, http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/his-darkened-imagination , accessed 8 June 2014.

See Matthew Withy, ‘A Fine Tomorrow: Sculpture and Socialism in Mid-Century Britain’, Henry Moore Institute Essays on Sculpture, no.39, 2003, p.7.

Henry Moore, response to questionnaire sent to members of Unit One, quoted in Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, London 1987, p.155.

The manifesto was published in the Studio in December 1934 (see Lynda Morris and Robert Radford, The Story of Artists International Association 1933–1953, Oxford 1983, p.13).

See foreword to Art for the People,exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1939 in Artists International Association file, Whitechapel Art Gallery Archive.

Brandon Taylor, Art for the Nation: Exhibitions and the London Public, 1747–2001, Manchester 1999, p.173.

Jill Craigin in Anthony Barnett’s ‘England’s Henry Moore’, dir. by Hugh Brody, television programme Channel 4, broadcast 1988.

Henry Moore quoted in Church of S. Matthew, Northampton, 1893–1943, http://www.henry-moore.org/works-in-public/world/uk/northampton/parish-church-of-st-matthew/madonna-and-child-1943-44-lh-226 , accessed 4 June 2014.

Ian McLean, ‘St. Matthew’s, Northampton, The Church with a Challenge’, Art Now, date unknown, pp.40–3.

McLean noted that this was an edited version of his remarks as his ‘actual words could find no place in this journal’, ibid., p.42.

Cora Gordon, ‘London Commentary’, Studio, vol.131, February 1946, p.94, quoted in Taylor 1999, p.168.

Robert Burstow, ‘”Sculpture in the Home”: Selling Modernism to Post-War British Homemakers’, Sculpture Journal, 17 February 2008, p.40.

John Berger, ‘Auntie Becomes Sally’, New Statesman and Nation, 29 October 1955, press cutting, Art and Design Archives, Arts Council Files, National Art Library ACGB 121/614.

Quoted in Becky Conekin, Frank Mort and Chris Waters (eds.), Moments of Modernity: Reconstructing Britain 1945–1964, London and New York 1999, p.234.

Ministry of Education Bulletin, no.1, October 1949, discussed in ILEA, ‘Paper for Discussion – Patronage and Encouragement of the Arts’, London Metropolitan Archives, ILEA/DE/17/001.

Anon., ‘”Belsen” Statue Came in the Night’, Daily Dispatch, 3 November 1950, press cutting, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Ibid. Forgetting he was being broadcast on live radio, Munnings launched into a tirade against Moore’s Madonna and Child sculpture in his speech at the Royal Academy’s Annual Summer Show banquet: ‘My horses may be all wrong but I’m damned sure that isn’t right’. On subsequently seeing Moore in the Athenaeum club he was heard to say, ‘What’s a bloody charlatan like him doing in this club?’ Kynaston 2007, pp.334–5.

R. Fogg, ‘An interview with Sir Alfred Munnings: Art and the Common Man’, East Anglian Times, May 1949, quoted in Taylor 1999, pp.200–1.

The works’ position was changed at the time of installation and even after the Festival opened, inaccurate records, altered titles and retrospective artists’ statements confused matters (see Robert Burstow, ‘Modern Sculpture in the South Bank Townscape’, Twentieth Century Society Journal, Architecture 5, ed. by Elain Harwood and Alan Powers, 2001, p.104).

George Melly and J.R. Graves-Smith, Cartoons about Modern Art: A Child of Six Could Do It, London 1973, p.71 (cartoon, Punch, 27 June 1951).

John Wyver, ‘Blog Archive, Moore Mondays 2’, Illuminations, 8 March 2010 http://www.illuminationsmedia.co.uk/blog/index.cfm?start=1&news_id=624 , accessed 10 November 2013.

Trevor Dannant, New Modern Architecture in Britain: Selected Examples of Recent Buildings, London 1959, p.20.

Anon., ‘Mr Moore’s “Family Group” Work Commissioned for New Town’, Times, 18 May 1956, page unknown.

Anon., ‘London Park Exhibit’, American magazine clipping, Arts Council Files, Archive of Art and Design, National Art Library ACGB/75/24.

Mrs G.R. Strauss interviewed by Dolores Mitchell, 4 June 1970, Dolores Mitchell collection of papers held by the author.

Isaac Hayward, foreword, Housing: A Survey of the Post-War Housing Work of the LCC 1945–49, London 1949.

The term ‘fine arts’ included music, opera, ballet, drama, literature, painting and sculpture. See The Arts Council of Great Britain: What It Is and What It Does, Southampton 1969, p.5.

Kenneth Campbell and B.A. Le Mare interviewed by Dolores Mitchell, 3 November 1969, Dolores Mitchell collection of papers held by the author.

Moore made a maquette for Fallen Warrior in 1956 but then altered the final composition of the resulting sculpture Falling Warrior 1956–7, moving the shield from near the figure’s right foot to the left hand (the figure in the maquette looked dead to him and he wanted rather to suggest a mortally wounded man using his shield to break his fall). See https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/moore-maquette-for-fallen-warrior-t06824 , accessed 13 November 2013.

Gabriel White, letter to W.O. Hart, clerk of the LCC, 27 May 1959, London Metropolitan Archives CL/GP/2/4.

Advisory Body on Art Acquisitions, memorandum, 27 July 1961, London Metropolitan Archives DG/AR/7/40.

Bernard Orna, ‘Antony Hollaway Artist for Architecture’, Studio, vol.167, no.85, February 1964, p.59.

Hollaway made abstract tile and mosaic murals for the internal lift halls of blocks 1 and 2, and a coloured glass resin and fibreglass mosaic for Block 3, all created in situ. He also created decorative paving slabs inlaid with coloured cement in a pattern of birds, fish, faces and abstract designs to break up the monotony of the concrete walkways.

A.L. Hollaway, ‘Art in Public’, M.A. dissertation, De Montford University 1995, section B, ‘Materials, Research and Development Through Art and Design Action’, vol.1, p.12.

The film Sparrows Can’t Sing (1963) was directed by Joan Littlewood and was based on a play ‘Sparrers Can’t Sing’, written by Stephen Lewis, first performed by the Theatre Workshop, run by Littlewoord, using improvisational theatre techniques, at the Theatre Royal, Stratford, in 1960.

Anon. (possibly the vicar of St. Dunstan’s Church), letter, East London Advertiser, 27 July 1962, page unknown.

Report by Clerk of the Council, Architect and Education Officer, 10 May 1963, London Metropolitan Archives ILEA/DE/17/0001.

In addition to the three LCC acquisitions, the Arts Council would also buy within the next year eight Moore sculptures and eight drawings below what was considered the market value.

British Library Sound Archive, National Life Story Collection, Architects’ Lives – Edward Hollamby (1921–1999), F5871A, p.67 (script version).

At Brandon Estate Hollaway created a fifty foot mosaic mural at the top of an eleven storey block, a neon ‘Hairy Mammoth’ sign for the exterior of the tenants’ clubroom, etched glazing and a sign for the public house, a twenty six foot mosaic mural located in the shopping precinct, a sgraffito low relief cement mural for the staircase leading to the tenants’ clubroom, a tile and mosaic mural for the interior of the tenants’ clubroom and a glass-reinforced aluminium relief for the clubroom entrance. This was all at a cost of £3,215, including his £1,760 annual fee. See Hollaway 1995, p.15.

Anon., ‘Boy Denies Damaging Valuable Statue’, Guardian, 26 September 1963, press cutting, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Henry Moore on ‘Face to Face: Henry Moore’, interviewed by John Freeman, television programme, BBC, broadcast 21 February 1960.

Henry Moore interviewed by Dolores Mitchell, ‘On Sculpture and Architecture’, Leonardo, vol.6, 1973, p.246.

Letter from Henry Moore’s secretary to Neal Baillie, 23 October 1963, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Hilary Spurling, ‘The Turbulent Reputation of Henry Moore’, Guardian, 27 February 2010, http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/feb/27/henry-moore-sculpture-tate-britain , accessed 24 January 2014.

Anthony Crosland in the Guardian, 16 June 1971, quoted in Nicholas Timmins, The Five Giants: A Biography of the Welfare State, London 2001, p.364.

Tony Parker, The People of Providence: A Housing Estate and Some of its Inhabitants, London 1983, p.289 (words in interview spoken by local social worker Ray Mills).

Secretary General’s Report, ‘Value for Money’, Arts Council of Great Britain, 32 Annual Report and Accounts 1976–7, p.8.

George Melly, Without Walls: J’Accuse Henry Moore, television programme, broadcast Channel Four 1993.

When the Greater London Council was disbanded by the Conservative government in 1985, the London Residuary Body was set up to oversee the transfer of functions and properties to successor bodies, such as local boroughs.

Keith Austin, ‘Big Bertha, You Either Love Her or Hate Her’, East London Advertiser, 18 October 1986, press cutting, Tower Hamlets Archive.

Anon., ‘She’s Back!’, East London Advertiser, 6 November 1987, press cutting, Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives.

Helen William, ’Old Flo’s on the Move Again’, East London Advertiser, 7 February 1992, press cutting, Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives.

The programme was part of a series that aimed to puncture ‘inflated reputations’. See John A. Walker, Arts TV: A History of Arts Television in Britain, Luton 1993, p.40.

Tony Banks, the Sports Minister, had worked for the Greater London Council during the 1980s and may have been aware of the LCC Patronage Scheme. See Trevor Phillips, ‘Cockney Charmer Who Stayed a Man of the People’, Daily Mail, 9 January 2006, p.19.

Anna Mainwaring, ‘Old Flo’s On the Go Again’, East London Advertiser, 12 March 1998, p.21, press cutting, Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives.

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.1 had also been housed at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park when the Chelsea College of Art and Design relocated to its new site next to Tate Britain. In this case, however, the sculpture was incorporated in plans for the new site, and students were re-introduced to it in 2010 through an exhibition titled Don’t Do any More, Henry Moore, which took as its focus the sculpture’s travels (http://www.chelseaspace.org/archive/moore-pr.htm , accessed 16 July 2014).

Sharon Ament, ‘Why Flo Mustn’t Go’, The Blog, Huffpost Culture United Kingdom, 13 November 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/sharon-ament/old-flo-tower-hamlets_b_2116347.html , accessed 13 November 2013.

Niru Ratnam, ‘Go with the Flow’, Spectator, 19 January 2013, http://www.spectator.co.uk/arts/arts-feature/8823941/go-with-the-flow/ , accessed 20 December 2013.

St Matthew’s Church, Northampton, Madonna and Child, 2014, http://www.stmatthewsnorthampton.org.uk/art_history_madonna_child.shtml , accessed 2 January 2014.

Dawn Pereira is an artist, teacher and writer, and a former Henry Moore Institute Research Fellow.

How to cite

Dawn Pereira, ‘Henry Moore and the Welfare State’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www