Henry Moore OM, CH Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Animal Head 1957, cast c.1957-62© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Animal Head

1957, cast c.1957-62

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

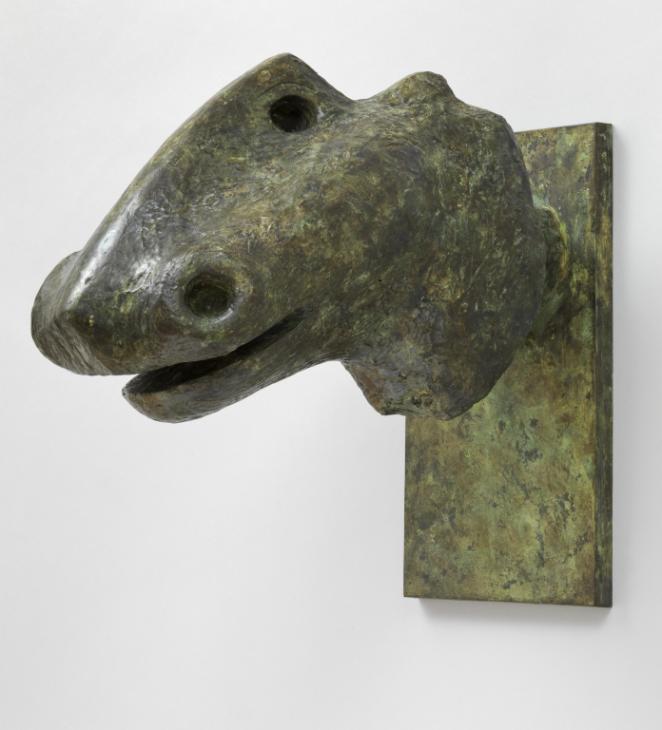

Animal Head is one of only two wall-mounted sculptures of animals made by Henry Moore. It does not depict a specific animal but is an amalgamation of the features of a number of different animals. Its formal origins may be traced to Moore’s interest in ancient and non-Western art forms.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Animal Head

1956, cast c.1957–62

Bronze

570 x 515 x 290 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02277

Animal Head

1956, cast c.1957–62

Bronze

570 x 515 x 290 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02277

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1962–3

Henry Moore: Sculptures, dessins, estampes, Galerie Gérald Cramer, Geneva, December 1962–January 1963, no.16.

1963

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston upon Hull, October–November 1963 (?another cast exhibited no.25).

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone, April–May 1966; City Art Gallery, Plymouth, June–July 1966, no.24.

1967

Henry Moore, Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield, July–September 1967, no.19.

1969

Henry Moore, University of York Visual Arts Society, Heslington Hall, York, March 1969, no.16.

1971

Henry Moore, Musée Rodin, Paris, 1971, no.37.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.32.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, no number.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March–August 1998, no.48.

References

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, p.108 (?another cast reproduced pl.103).

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1960 (another cast reproduced fig.43).

1962

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, M. Knoedler and Co., New York 1962 (another cast reproduced p.23).

1963

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Art Center, La Jolla 1963 (another cast reproduced).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.224 (?another cast reproduced pl.211).

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo 1968 (another cast reproduced no.91).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968 (?another cast reproduced p.265).

1971

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Musée Rodin, Paris 1971, reproduced no.37.

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977 (another cast reproduced, pp.176–7).

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Bradford Art Galleries and Museums, Bradford 1978, reproduced no.32.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.34.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, p.144 (original plaster reproduced pl.116).

1981

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2277 Animal Head’, The Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1978–80, London 1981, pp.118–19.

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983, reproduced p.90.

1983

W.J. Strachan, Henry Moore: Animals, London 1983, p.127, reproduced pl.116.

1986

Alan Bownesss (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, no.396 (?another cast reproduced pls.14–15).

1987

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987 (maquette and plaster original reproduced p.166).

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, p.238 (another cast reproduced no.137).

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998, pp.299–300, reproduced p.196.

2006

Reinhard Rudolph, ‘Animal Head, 1955’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.250 (dated ‘1955’).

Technique and condition

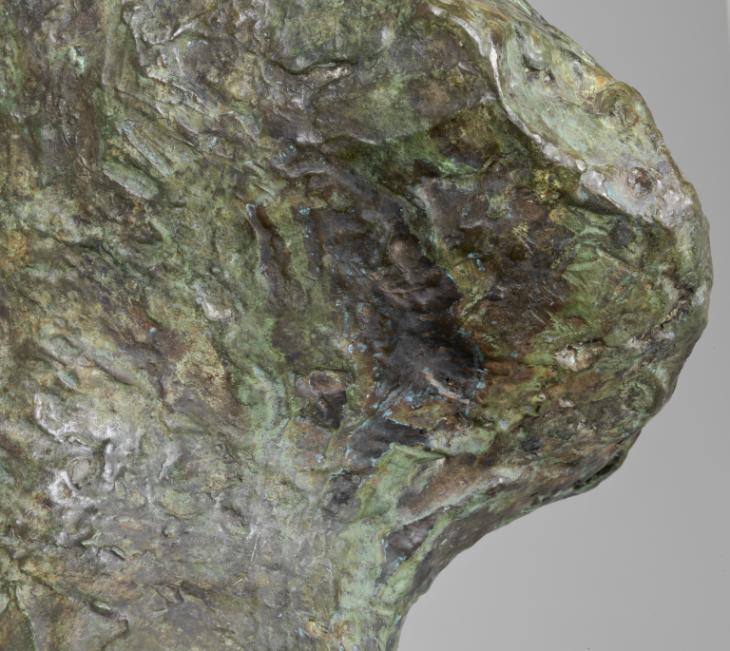

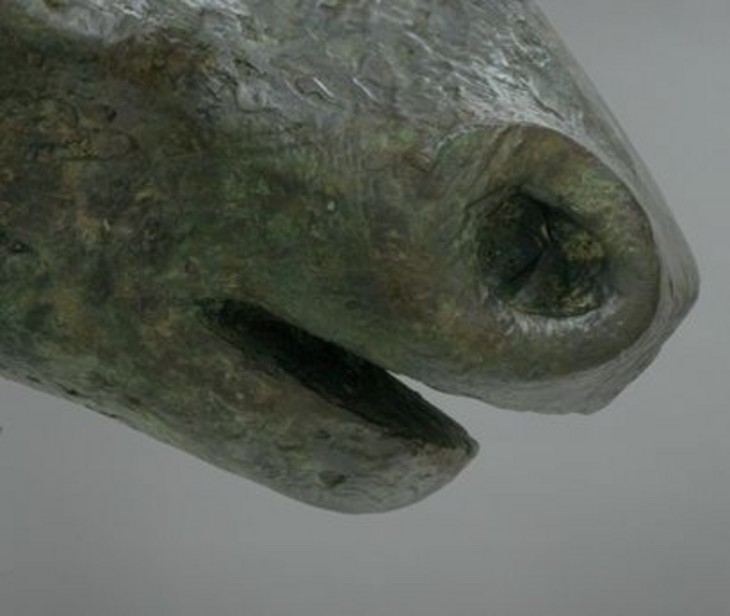

This sculpture of an animal head and neck is made of bronze and attached to a rectangular bronze wall mount so that the head projects out at a perpendicular angle from the wall on which it is displayed. The head does not seem to represent any specific animal although it has both bovine and equine characteristics. The eyes are represented by a single hole that runs through the top of the head. There is an eyebrow inscribed above the eye on the animal’s left side (fig.1).

Detail showing eye hole and eyebrow of Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail showing eye hole and eyebrow of Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Rear of mount of Animal head 1956, cast c.1957–62

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Rear of mount of Animal head 1956, cast c.1957–62

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

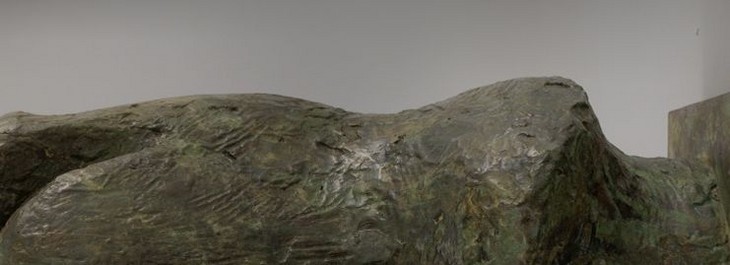

The neck is attached to its mount by threaded brass rods that protrude from the back of the mount and are secured with brass nuts (fig.2). The sculpture is fixed to the wall by means of a custom-made wall plate that hooks onto a cast-in bracket at the back of the mount.

Detail of Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62 showing traces of investment

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62 showing traces of investment

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of mottled patination on the surface of Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of mottled patination on the surface of Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

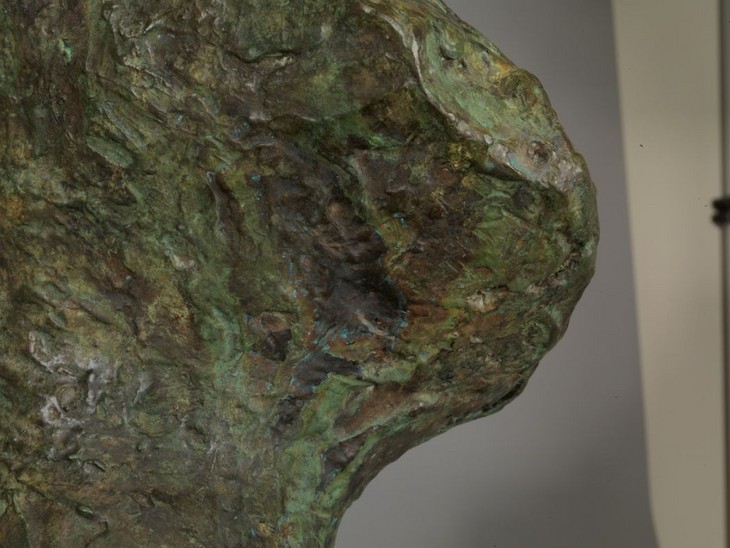

The bronze on the head and neck has a highly modelled surface. To make this sculpture Moore would have created an initial model from which a mould was taken in which the bronze could be cast. Deep striations and marks from the thickly applied modelling material suggest that he made the original model in plaster, probably using a wire or wood armature for internal support. Some small traces of investment can be seen in crevices (fig.3), and on the back of the mount showing that the bronze was cast using the lost wax process. There are no inscriptions on the bronze.

The bronze was chemically patinated at the foundry using a number of different chemical solutions applied with a brush in layers that reacted with the bronze to give different coloured compounds. In this case the sculpture and the mount have the same patina of mottled brown and green (fig.4). The first layer applied to the bronze would have been a dark brown, probably created using a solution of potassium polysulphide (known in foundries as ‘liver of sulphur’). After this, a blue green patina was stippled over the top. There are many different patina recipes used to produce green colours on bronzes but they often contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts dissolved in water. Finally an orange-brown patina was stippled over the green to produce the more muted final shades. This type of colour is often created by using ferric nitrate solution. The entire patinated surface has been given a layer of wax to consolidate and protect the patina.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, February 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

This is a wall mounted hollow sculpture of an animal’s head. The sculpture is not a naturalistic representation of a real animal, but appears to combine both equine and bovine features. Animal Head seems to depict a living animal and has a distinctive facial expression.

From its vertically positioned rectangular mount the animal head projects outwards horizontally from the wall, like a gargoyle. At the rear of the head, a tubular neck joins the sculpture to the mount and sits flush on the surface.

At the top of the head the tubular neck extends into a thin peaked ridge, creating a jagged profile and a noticeable v-shape behind the eyes, which are denoted by a single hole or tunnel that runs straight through this ridge linking the two sides of the head. The opening of the hole on each side thus represents a single eye (fig.1). A curved eyebrow has been incised above the eye on the right-hand profile. From the triangular point above the eyes the nasal bone runs the length of the head, terminating in a slight point at the front of the sculpture. This point or tip is flanked on either side by two large nostrils, each denoted by large domed indentations with protruding circular edges (fig.2). The nostrils are aligned on either side of the head like the eyes, although here the indentations do not join up to create a single hole. The muzzle or snout of the animal is quite wide and, together with the shape of the nostrils, resembles that of a hippopotamus. Below the muzzle is an open mouth, denoted by a thin but deep gap between the upper snout and the projecting mandible, or lower jaw (fig.3).

Henry Moore

Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62 (front view)

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62 (front view)

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of mouth of Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of mouth of Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The various features of the head are not arranged symmetrically like those of real animals. The cheekbone on the left is much more pronounced than that on the right-hand side, emphasised by a recession behind the nostril. The line from the ridge of the nasal bone to the edge of the left cheek bone is a much steeper and longer diagonal compared to that of the right, which is much fuller and rounder. The left cheekbone extends backwards behind the eye socket and curves inwards to form the nape of the neck.

On the right side of the animal head the neck is quite broad and creates a half oval shape that is set in front of the hanging plate. Seen from a side position it appears that the neck, which links the head to the mount, is actually the internal vertebrae or spinal column, and not a fully developed neck muscle (fig.4).

The surface of the sculpture is textured but not rough, and tool marks are visible in the form of horizontal lines where the original plaster was modelled (fig.5). Because the surface of the sculpture is not smooth, the bronze has a slightly weathered appearance, and traces of plaster investment embedded within crevices can be seen in places (fig.6). The weathered appearance of the sculpture is accentuated by the stippled green-brown colouring of the bronze. This mottled colouring has been achieved by the application of chemical patinas, and it is notable that the patination is not exclusive to the head itself, but has also been applied to the rectangular mount.

Henry Moore

Detail showing textured surface and tool marks on Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Detail showing textured surface and tool marks on Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62 showing traces of investment

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62 showing traces of investment

Tate T02271

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Animal head 1956

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Animal head 1956

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In order to cast the sculpture in bronze Moore first made a small maquette in plaster to test the three-dimensional design. When Moore was happy with how it looked the maquette was then scaled-up to a full-size plaster version (fig.7). However, Moore noted that during the scaling-up process, ‘changes will be made before going to the real, full-sized sculpture. Changes get made at all ... stages’.1 The slight differences between the maquette and the full-size plaster, such as the latter’s more pronounced nostrils, were made when Moore adjusted the forms to suit the larger size.

It is likely that Moore made these plaster versions in his small maquette studio in the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. Moore had moved to Hoglands in 1940 and the studio, which was formally the village shop, was set up a few years later. Now known as the Etching Studio, it was initially used for creating small plaster sculptures and ‘remained Moore’s principal creative space until 1970, when it was superseded by the purpose-built Bourne Maquette Studio’.2 The small plaster studio was lined with shelves that housed Moore’s ever growing collection of found bones, skulls, and pebbles, which he called his ‘library of natural forms’.3 Surrounded by these objects, it is likely that Moore borrowed shapes from a variety of sources with the result that although Animal Head does not present a real animal, it does nonetheless contains zoological traits.

In order to make the plaster original Moore built up layers of plaster on an armature. In 1960 Moore explained, ‘You need an armature because, with plaster sculpture, you have to build on something or you’d have a great big solid piece of plaster which is unhandleable ... so one makes an armature in wood with, perhaps chicken wire roughly to shape’.4 As the layers of plaster were added and the sculpture became denser, its individual forms and shapes could then be modelled. According to Moore, ‘The advantage of using plaster is that it can be both built up, as in modelling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.5 In this way, Moore has able to build up the animal head and then carve out the tunnel for the eyes and the gap for the mouth.

Moore did not cast the ten bronze versions of Animal Head himself but instead entrusted the job to the Fiorini Art Bronze Foundry in London, which he had previously commissioned to cast his Family Group 1949 (Tate N06004). Although Fiorini initially had problems casting works on the large scale of this earlier sculpture, Moore nonetheless continued to use them throughout the 1950s, and the foundry cast a selection of Moore’s sculptures including Falling Warrior 1956–7 (Tate T02278). At the foundry the technicians used the plaster original to create a hollow mould into which molten bronze could be poured, and from which the multiple bronze versions could be made. According to records held in the Henry Moore Foundation Archive, the plaster original was sent to the foundry on 6 November 1957 and the ten bronze versions were cast over the subsequent five years. It is uncertain when exactly Tate’s copy was cast.6

The resultant bronze version of Animal Head looks very different from its plaster original. The off-white colour of the plaster held in the Art Gallery of Ontario is suggestive of bone and thus the sculpture could be said to resemble a skull more than a living head. However, not only does the stippled green and brown colour of Tate’s bronze example obscure this resemblance to bone, but the forms of the bronze, such as the muzzle and the underside of the jaw, appear heavier and more muscular than they do in the plaster. Moore later recalled that:

When working in plaster for bronze I need to visualise it as a bronze because on white plaster the light and shade acts quite differently, throwing back a reflected light on itself and making the forms softer, less powerful ... even weightless.

At first I used to have a tremendous shock going from the white plaster model to the finished bronze sculpture ... The main difference is that bronze takes on a density and weight altogether unlike plaster. Plaster has a ghost-like unreality in contrast to the solid strength of the bronze.7

At first I used to have a tremendous shock going from the white plaster model to the finished bronze sculpture ... The main difference is that bronze takes on a density and weight altogether unlike plaster. Plaster has a ghost-like unreality in contrast to the solid strength of the bronze.7

After casting at the foundry the bronze sculptures were returned to Moore so that he could check the quality of the casting and make decisions about the patination. A patina refers to the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze sculpture. In 1960 Moore explained:

I like working on all my bronzes after they come back from the foundry. A new cast to begin with is just like a new-minted penny, with a kind of slight tarnished effect on it. Sometimes this is right and suitable for a sculpture, but not always. Bronze is very sensitive to chemicals, and bronze naturally in the open air (particularly near the sea) will turn with time and the action of the atmosphere to a beautiful green. But sometimes one can’t wait for nature to have its go at the bronze, and you can speed it up by treating the bronze with different acids which will produce different effects. Some will turn the bronze black, others will turn it green, others will turn it red.8

According to curator Julie Summers, Moore sought to ‘produce a unity between patina and form’ in his sculptures, so that the colours complimented the shapes on which they were applied.9 In the case of Animal Head Moore attempted to replicate natural weathering by applying sea-green patina to the surface of the sculpture. Moore may well have chosen to give it the appearance of having been weathered naturally in the open air because the sculpture represents the head of an animal that lives outside. Moore noted that when working on his plasters he normally had a preconceived idea of what colour the sculpture would eventually take:

I usually have an idea, as I make the plaster, whether I intend it to be a bark or a light bronze, and what colour it is going to be. When it comes back from the foundry I do the patination and this sometimes comes off happily, though sometimes you can’t repeat what you’ve done other times. The mixture of bronze may be different, the temperature to which you heat the bronze before put the acid on to it may be different. It is a very exciting but tricky and uncertain thing, this patination of bronze.10

According to Summers, Moore looked upon the difficultly of replicating patinas not as a problem but as a possibility, whereby he was able to vary and experiment with colour within an edition. Moreover, Summers noted that ‘a variation in colour within the edition also represented an element of choice for the potential client’.11 The patination of Tate’s Animal Head is significantly different to the examples held in the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. While Tate’s example has a slightly mottled brown-green patina, the example in the Kröller-Müller Museum is coloured with an even, dark brown-black. This colouring may best suit the sculpture’s placement outside; were the sculpture a mottled green it might not stand out against its leafy surroundings. The example held in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art has much more dramatic variations of patina. Although Moore used the same green-brown colour palette as the Tate version, the browns in the Kansas work have been applied to very distinct areas, for example on the lower right of the mount. Furthermore, the ridge of the nasal bone, the rim of the nostril and the cheekbone have been polished to produce a shine. As Moore explained in 1960, after patination ‘you can then work on the bronze, work on the surface and let the bronze come through again ... You rub it and wear it down as your hand might by a lot of handling. From this point of view bronze is a most responsive and unbelievably varied material’.12

Moore made his first sculpture of an imaginary animal head in 1921 (Small Animal Head, The Henry Moore Foundation), and although the subject occurred infrequently in his work it was nonetheless one that he liked to return to, with the last examples being made in the early 1980s. Indeed, as early as 1934 the critic Herbert Read identified animals as one of Moore’s key interests. Although written well before the creation of Animal Head, Read’s observations remain relevant. According to Read, Moore’s animal sculptures were reduced to certain basic shapes or features in an attempt to convey the animal’s inner character.13 Moore’s animals, Read argued, did not aspire to anatomical accuracy but were presented in distilled, unembellished forms that conveyed their inherent life force, or essence. Moore himself remarked later that ‘People will accept alterations and distortions in animals quite happily, whereas the same degree of distortion in the human figure would upset them’.14

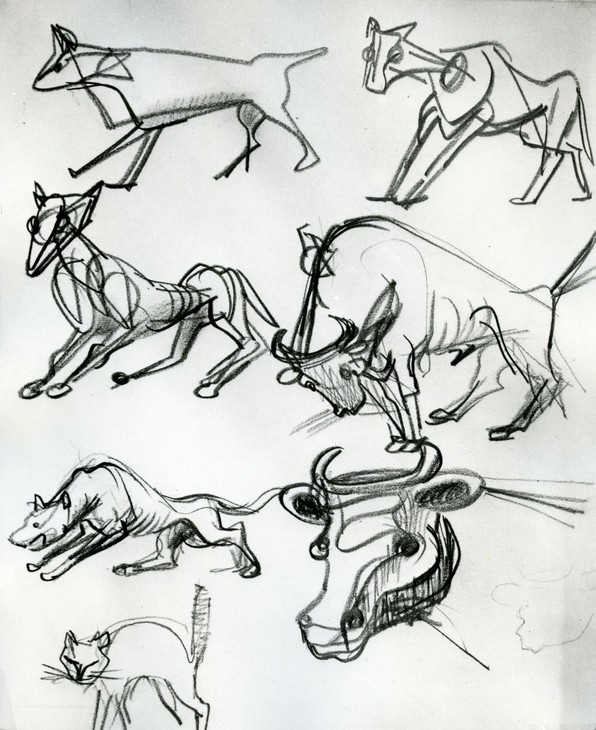

In the introduction to his 1983 publication Henry Moore: Animals, author W.J. Strachan noted that ‘between 1921 and 1982 Henry Moore has made fifty-eight animal sculptures and has drawn many scores of animals – domestic, wild, fantastic’.15 Moore’s sculptures can rarely be linked directly to preparatory drawings, and as his career progressed he made fewer and fewer sketches for specific works, preferring instead to test out ideas in small hand-held sculptures. Many of these three-dimensional ideas never progressed beyond the test stage, but some, such as Animal Head, were developed into a small maquette and then a full-size plaster. However, although Moore made fewer sketches for sculpture by the 1950s he did continue to draw, and these works on paper may have contributed to the eventual form of his sculptures.

In 1950 Moore drew seven pages of animal heads and fantastical animals. Although the order in which Moore made these drawings is uncertain, it is possible that he began with some naturalistic sketches, such as that of the cow’s head in the lower right of Animal Studies c.1950 (fig.8), and developed these into more abstract creatures, as seen in Animal Heads c.1950 (fig.9).16 These drawings reveal that Moore was aware of the anatomical structure of animals, and was curious about how these living beings might be expressed artistically.

Henry Moore

Animal Studies c.1950

Graphite on paper

289 x 238 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Animal Studies c.1950

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Animal Heads c.1950

Graphite, wax crayon and watercolour wash on paper

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Animal Heads c.1950

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

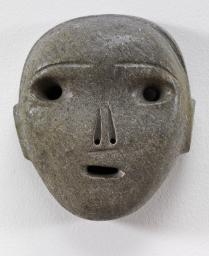

Strachan identified hippopotamus-like forms in the bronze Animal Head stating, ‘the wide “snorting” (Moore’s word) nostrils, the eye placed high on the dome of the skull give it a prehistoric appearance emphasised by the hatched texture suggesting a pachyderm’.17 The curator Alan Wilkinson noted that the original plaster of Animal Head held in the Art Gallery of Ontario is an imaginative amalgamation of zoological forms and ‘might well have been given a title like Horse’s Head, Dinosaur’s Head or Head of a Prehistoric Animal’.18

Head of the cow of Hathor from Deir el-Bahari, Egypt c.1450 BC

Alabaster

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.10

Head of the cow of Hathor from Deir el-Bahari, Egypt c.1450 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Head of Serpent 1927

Stone

object: 180 x 114 x 114 mm

Lent from a private collection 1994

On long-term loan to Tate L01766

On long-term loan to Tate L01766

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore OM, CH

Head of Serpent 1927

Lent from a private collection 1994

On long-term loan to Tate L01766

On long-term loan to Tate L01766

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s decision to create a sculpture in this gargoyle-like form in 1956 was unusual. Since the 1930s he had championed the idea that sculpture should exist in the round, emphasising its three-dimensionality. In its elevated position mounted on a wall, the rear and possibly the top of Animal Head remain imperceptible to viewers. However, Rudolph noted that the year prior to making Animal Head Moore had created a series of wall reliefs and it is possible that this engagement with sculpture for architecture led him to re-visit wall-mounted sculpture.

Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62 on display in the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62 on display in the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Animal Head exists in an edition of ten bronze casts plus one artist’s proof. One of these is held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation while other examples are held in the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. The remaining bronze examples are held in private collections. The original plaster and the plaster maquette are held in the Moore Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto.

Alice Correia

February 2013

Notes

Henry Moore in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, p.113, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.226.

Henry Moore cited in John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore: My Ideas, Inspiration and Life as an Artist, London 1986, p.159.

Julie Summers, ‘Gilding the Lily: The Patination of Henry Moore’s Bronze Sculptures’, in Jackie Heuman (ed.), From Marble to Chocolate: The Conservation of Modern Sculpture, London 1995, p.145.

This developmental sequence is based on the way in which these drawings are presented in the artist’s catalogue raisionné, where Animal Studies c.1950 is listed before Animal Heads c.1950. See Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Drawings 1950–76, London 2003, p.20.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.166.

See for example, Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art and the Post-Columbian World: Ancient American Sources of Modern Art, New York 2000, p.122; and Strachan 1983, pp.14–18.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeny, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.44.

In his introduction to the book Moore concluded that ‘It has been a wonderful experience for me to recapture the delight, the excitement, the inspiration I got in these pieces as a young and developing sculptor’. Henry Moore, Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981, p.16.

Reinhard Rudolph, ‘Animal Head, 1955’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.250.

Related essays

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Animal Head 1956, cast c.1957–62 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, February 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www