Henry Moore OM, CH Mask ?1928

Image 1 of 9

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Mask ?1928© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Mask

?1928

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

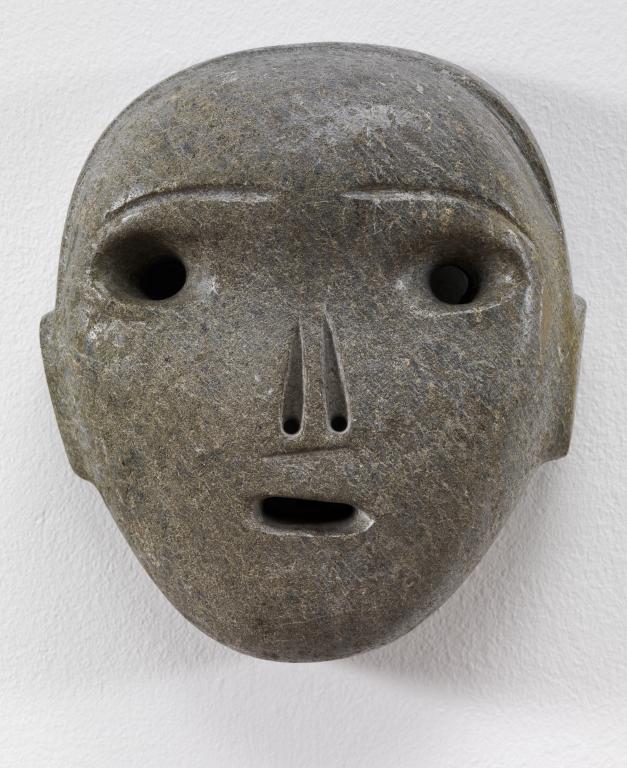

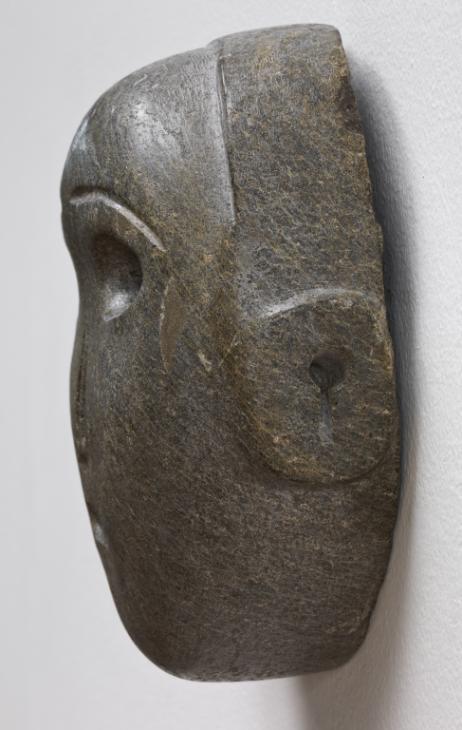

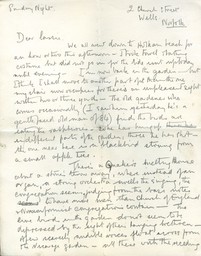

One of a series of masks made between 1924 and 1930, this sculpture reflects Moore’s interest in the arts of ancient Mexico. It is notable for its expressive asymmetry and is one of the first instances of Moore’s use of holes in sculpture.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Mask

?1928

Green gneiss stone

212 x 190 x 87 mm

Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund 1993

T06696

Mask

?1928

Green gneiss stone

212 x 190 x 87 mm

Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund 1993

T06696

Ownership history

Acquired by Raymond Coxon, London, by 1951, by whom sold to Marlborough Fine Art, London, 24 June 1964; bought by Sir Alistair McAlpine, London, on 23 April 1966, by whom sold at Sotheby’s, London (date unknown), where bought by Mrs Lewis Cohen; purchased by Tate through Browse and Darby, London, in 1993 with assistance from the National Art Collections Fund.

Exhibition history

1951

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, May–July 1951, no.45 (dated c.1928).

1955

Moderne Kunst: Nieuw en Oud, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, July–October 1955.

1961

Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carvings, Marlborough Fine Art, London, June–July 1961, no.30.

1966

Henry Moore, Marlborough Fine Art, London, July–August 1966, no.3 (dated c.1928).

1967

Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Paintings, Drawings and Sculptures, David W. Hughes, London, Summer 1967, no.40.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.7.

2006

Henry Moore, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona, July–October 2006, no number.

2010–11

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 2010–February 2011; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011, no.14.

References

1951

David Sylvester (ed.), Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1951, unpaginated (noting Raymond Coxon as owner).

1955

Moderne Kunst: Nieuw en Oud, exhibition catalogue, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam 1955, reproduced on front cover.

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, London 1957, no.54, reproduced p.9 (noting Raymond Coxon as owner; dated ?1928).

1961

Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carvings, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1961, pl.1.

1994

Tate Gallery Biennial Report 1992–94, London 1994, p.56.

2000

Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art and the Post-Columbian World: Ancient American Sources of Modern Art, New York 2000, reproduced p.108 (as Skull Mask).

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced pp.24, 37.

2006

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona 2006, reproduced on front cover and p.67.

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007, reproduced p.25.

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced no.14.

Technique and condition

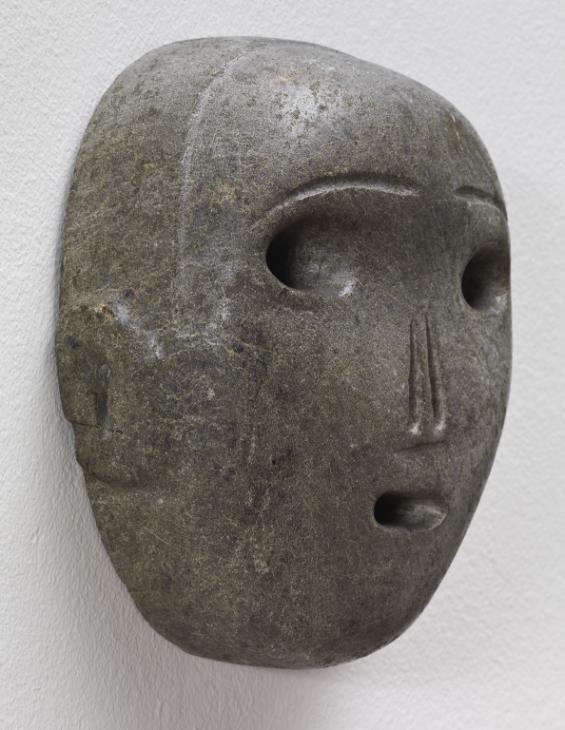

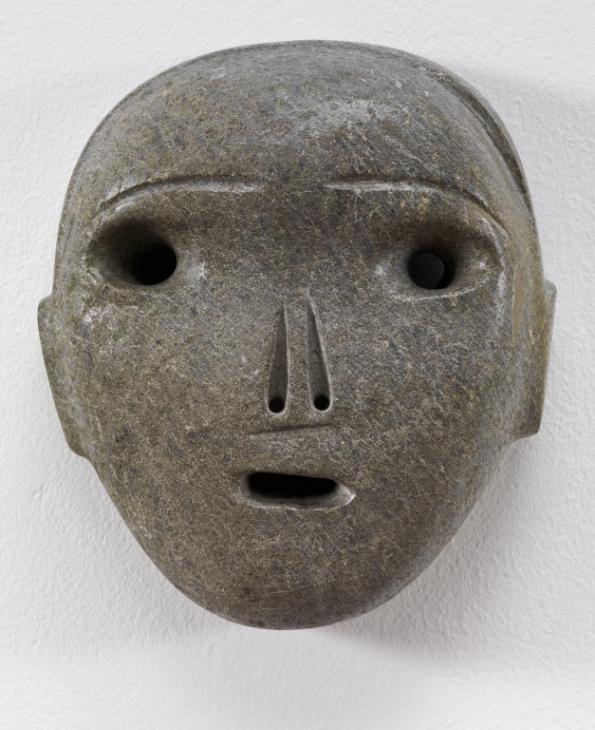

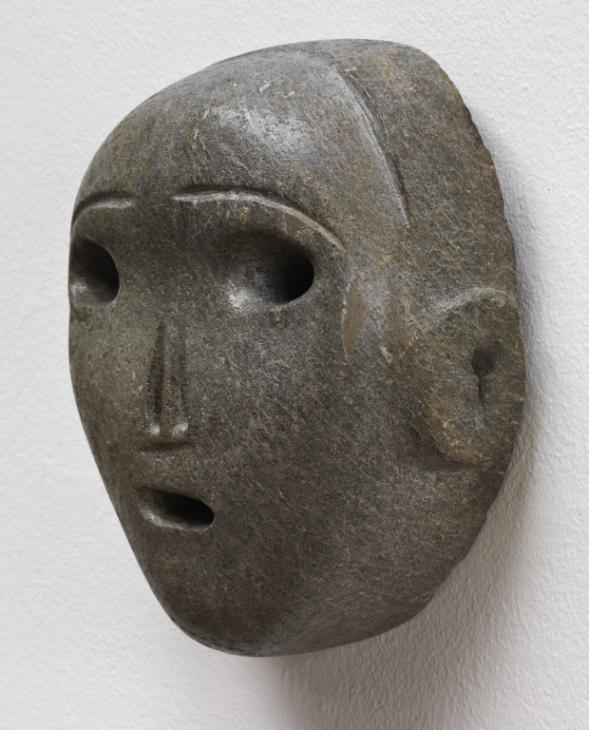

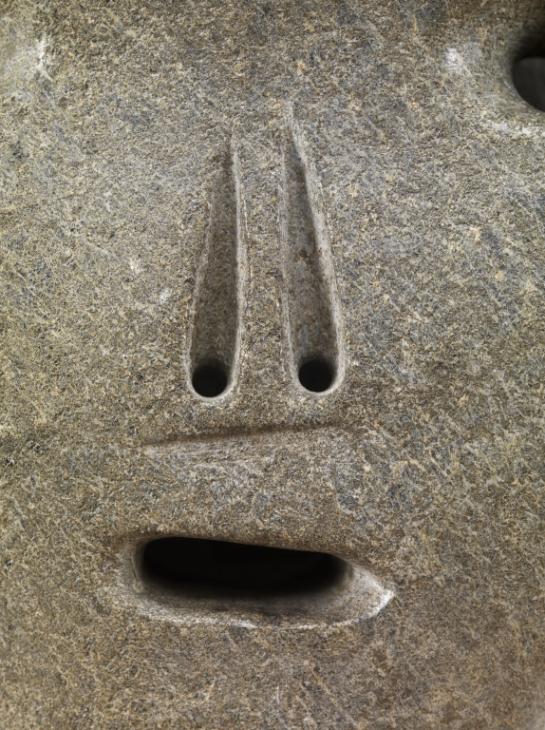

This is a small, wall hung sculpture of a mask of a human face carved in green gneiss, a hard metamorphic stone similar to granite. The front surface of the mask is smooth with a slight polish. Moore would have roughed out the form using chisels of various types and sizes before filing and sanding the stone to achieve the final smooth finish. Pierced holes and grooves represent the eyes, ears, nostrils and mouth; the holes made for the eyes and mouth penetrate right through to the back of the mask. To either side are two raised oval shaped ears given form with the addition of a drilled and carved keyhole shape at the centre of each. The eyebrows are indicated by long, thin grooves in the surface, and the hairline has been carved so that it is slightly in relief. Fine chisel and file marks are visible in these areas showing how Moore worked the stone (fig.1). Moore chose to carve out the back of the sculpture, mimicking masks that are made to be worn on the face, leaving a smooth flat rim around the edge. This allows the mask to rest flush with the wall so that the back is not visible when on display. He left the hollowed surface rough and the grooves made by point and claw chisels are still clearly visible (fig.2). There is no inscription.

Detail of Mask 1928 showing fine chisel marks

T06696

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of Mask 1928 showing fine chisel marks

T06696

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Rear of Mask 1928 showing heavy chisel grooves and fixing

T06696

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Rear of Mask 1928 showing heavy chisel grooves and fixing

T06696

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This artwork would originally have had relatively simple fixings and the mask would have hung on a single screw or hook. A two-piece stainless steel fixing system has subsequently been devised and embedded into the back of the mask at the top and centre to keep the mask safely on the wall during public display.

There are small fills to the left of the left eye and above on the left eyebrow. These are not recent and could have been carried out during fabrication to cover flaws in the stone. The surface of the stone is lightly waxed to enhance the shine and protect the surface.

Lyndsey Morgan

October 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', October 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Mask ?1928 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Although its title identifies it as a mask, this sculpture was not designed to be worn but displayed on a wall. The sculpture is almost heart-shaped, with a wide forehead and hairline tapering to a narrow chin. Holes have been used to denote the eyes, nostrils and mouth, and run right through the stone. Thin, incised eyebrows balance the face but the other features are subtly asymmetrical: the eye on the viewer’s left, for example, is larger than the one on the viewer’s right. The nose is indicated by a pair of thin grooves – one marginally longer than the other – terminating in two small round holes. Beneath, a faint diagonal incision marks the end of the nose, while a slightly tilted and flattened oval-shaped hole denotes the mouth, seemingly caught mid-speech or in surprise. Oval-shaped ears, marked with keyhole-shaped recessions, complete the head. When viewed in profile the sculpture does not show any great variation in depth or protrusion.

Mask was carved in green gneiss stone, which has fine white and orange-brown veining. Gneiss stone is a metamorphic rock found internationally as well as in some parts of Britain. The stone is often identified as marble or granite due to its similarities in hardness and veining. The front and rear of Mask bear the marks of a number of different stone carving tools and would have been carved and polished by hand. The front surface, which is generally smooth, is scattered with small, shallow areas of rough stone giving it a weathered appearance. The back surface has been hollowed out and shows rough tooling marks.

When it was accessioned into the Tate collection Mask was deemed to have been made in 1928, but there is some uncertainly over the accuracy of this date.1 In Moore’s catalogue raisonné published in 1957 the critic and curator David Sylvester, who edited the volume, noted that although ‘dates have been carefully checked and counter-checked ... those which are still in any way conjectural are prefixed with a question mark’.2 Sylvester, with Moore’s approval, dated Mask ‘?1928’.3 This dating seems reasonable given that between 1928 and 1929 Moore made at least seven other sculptures of masks, created in a range of different types of stone and concrete.4

During the late 1920s, when he carved this and his other mask sculptures, Moore was working as a tutor at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London. He had moved to the capital in 1921 to study at the RCA and, following his graduation in 1924, took up the post of Assistant in the Sculpture Department, a position he held until 1931. With a secure income of £240 per annum, Moore was able to pursue his own artistic interests outside of his teaching hours. Although nothing is known about the precise circumstances in which Mask was made, it was probably carved at Moore’s studio, 3 Grove Studio, Adie Road, Hammersmith, where he lived and worked between 1926 and 1929.

Mask was made at a moment at which Moore’s career and reputation began to accelerate: in January 1928 he had his first solo exhibition, held at the Warren Gallery, London, and received his first public commission. Although Mask was not included in the Warren Gallery exhibition (an omission which suggests that it had not been created by this date), critical responses to the show are nonetheless useful for understanding the context in which it was made. Although some reviews were negative, most concurred that Moore was an artist with potential. For example, the reviewer for the Times concluded that although Moore’s abilities as a carver were not in doubt, ‘his actual sense of form is not yet highly developed’.5 The most extreme response came from the reviewer for the Westminster Gazette, identified only by their initials P.M-W, who described the sculptures as ‘tortuous twistings of stone, marble and wood’ and trusted that the majority of the exhibition’s visitors would find Moore’s work ‘ugly’.5

Henry Moore

Mask 1924

Verdi di prato

178 mm

Whereabouts unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Mask 1924

Whereabouts unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

It was Roger Fry’s influential book Vision and Design (1920), which Moore read while studying at Leeds School of Art in 1920, that first sparked Moore’s interest in the arts of ancient Mexico. Fry was a founding member of the Bloomsbury Group of artists and writers and a highly regarded art critic, and Vision and Design included chapters on African, Islamic and ancient American arts. Fry highlighted that ‘more recently we have come to recognise the beauty of Aztec and Mayan sculpture, and some of our modern artists have even gone to them for inspiration’.8 Indeed, by the early years of the twentieth century many artists and critics believed that the art of so-called ‘primitive’ civilisations (non-Western or ancient cultures) offered a more emotionally direct antidote to the stylised sophistication of Western art in the classical tradition. By emulating primitive artistic sources, artists found ways of challenging the pre-eminence of academic art with its focus on anatomical accuracy and technical virtuosity.9 As the art historian Christopher Green has suggested, for Fry and many others, the turn to primitive art ‘offered a stimulus for rebuilding the broader terms of the European tradition’.10

The art historian Charles Harrison has suggested that Moore’s particular interest in the art of ancient Mexico in the 1920s ‘served to establish his idiosyncrasy among those following the fashion for “primitive” art’.11 In 1941 Moore explained that ‘Mexican sculpture, as soon as I found it, seemed to me true and right’, elaborating that he admired Mexican sculpture for ‘its tremendous power without loss of sensitiveness, its astonishing variety and fertility of form invention’.12 As a student Moore had studied examples of ancient Mexican sculpture in the British Museum and in 1947 he recalled, ‘One room after another in the British Museum took my enthusiasm. The Royal College of Art meant nothing in comparison ... And after the first excitement it was the art of ancient Mexico that spoke to me most’.13 The British Museum had a particularly large collection of ancient Mexican sculpture having acquired its first piece in the 1820s and Moore may have also visited the museum’s 1923 exhibition of Mayan sculpture from the Maudlay Collection.14

Moore was not alone, however, in his interest in the arts of the ancient Americas. Braun notes that throughout the 1920s there was a growth in exhibitions, publications and public interest in ancient Mexican and pre-Columbian, South American art, fuelled by numerous archaeological discoveries.15 These included the 1926 archaeological excavations of an ancient Mayan city in British Honduras (present-day Belize), led by the British Museum’s ethnographic curator Thomas Joyce. These excavations were widely reported in publications such as the Times and the London Illustrated News, and Moore was one of a number of British artists and writers including Leon Underwood and D.H. Lawrence who were looking to the arts and culture of ancient Mexico for inspiration.16 Indeed, Underwood, who had been Moore’s life-drawing tutor at the RCA in 1921 and with whom Moore remained close until the early 1930s, visited Mexico in 1927 and painted a number of works depicting Chacmool, a rain spirit of the ancient Toltec-Maya culture.17 Given their friendship during the 1920s it is likely that Moore and Underwood discussed their shared interest in the arts of ancient Mexico.

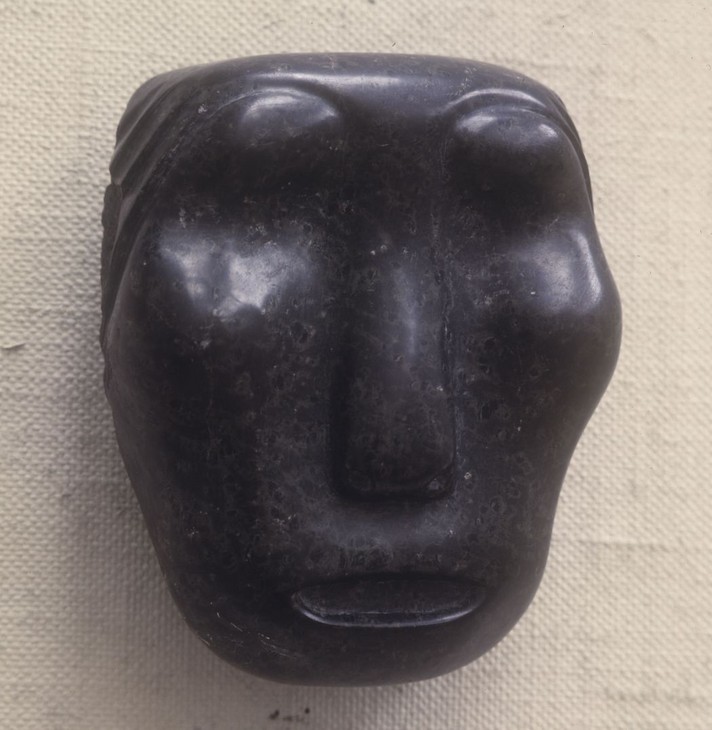

Henry Moore

Circus Drawings and Study of a Mexican Head (from Notebook No.6), 1926

Graphite on paper

223 x 170 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Circus Drawings and Study of a Mexican Head (from Notebook No.6), 1926

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

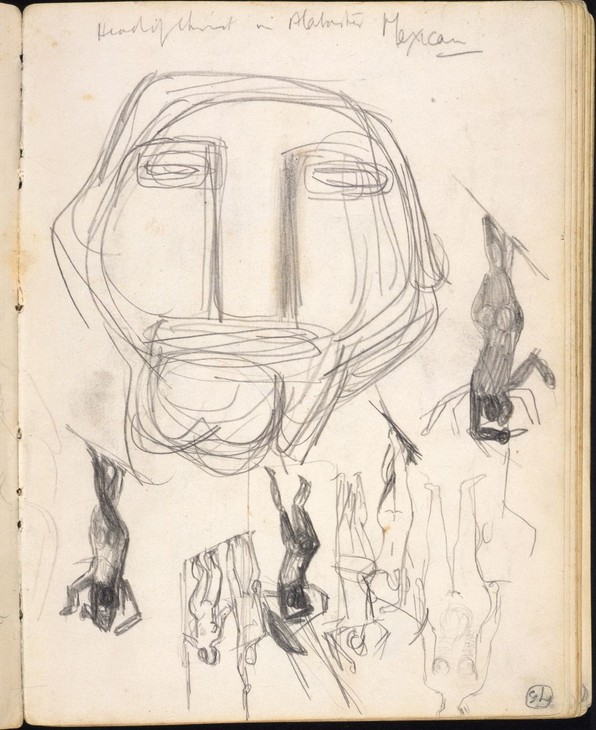

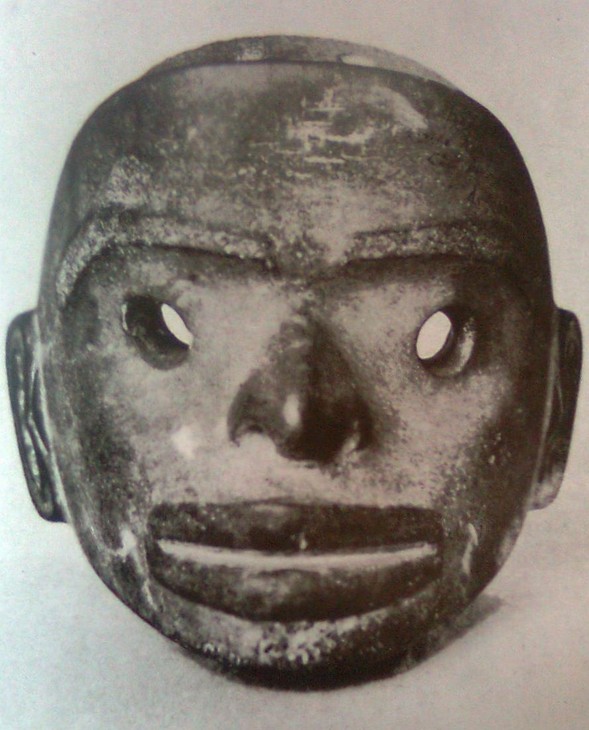

Head of a Man from Mezcala, Guerrero, Mexico c.1200–1521

Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna

reproduced in Ernst Fuhrmann, Mexiko III, Hagen 1922, pl.22

Fig.3

Head of a Man from Mezcala, Guerrero, Mexico c.1200–1521

Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna

reproduced in Ernst Fuhrmann, Mexiko III, Hagen 1922, pl.22

Moore supplemented his studies in the British Museum by reading a variety of recent publications. He later recalled that, ‘Fry opened the way to other books’,18 and he sought out and examined texts that were either cited in Vision and Design or that elaborated on its various subjects. In 1923 Moore bought copies of Ernst Fuhrmann’s Mexiko III (1922), which contained numerous black and white illustrations of ancient Mexican masks, figurative and animal sculptures, and Fuhrmann’s Reich der Inka (1922). Moore later returned to Fuhrmann’s publications and Herbert Kühn’s Die Kunst Der Primitiven (1923) in 1926 when he made a series of drawings based on their reproductions. For example, Moore’s sketch annotated ‘Head of Christ in Alabaster / Mexican’ (fig.2) is a direct copy of the alabaster sculpture Head of a Man, illustrated in Fuhrmann’s Mexiko III (fig.3).19 Despite art historian Alan Wilkinson noting in a text about Moore’s drawings that ‘in view of Moore’s admiration for Mexican sculpture, it is somewhat surprising to find so few copies of individual works’, it is clear that pre-Columbian art provided inspiration for Moore’s sculptural work during the 1920s, in particular his series of masks and Head of a Serpent 1927 (Tate L01766), which relates to Moore’s study of Aztec snakes.20

Mask from River Nass region, British Columbia, Canada (undated)

220 x 220 mm

Musée de l'Homme, Paris

reproduced in Adolphe Basler and Ernest Brummer, L'Art précolombien, Paris 1928, pl.61

Fig.4

Mask from River Nass region, British Columbia, Canada (undated)

Musée de l'Homme, Paris

reproduced in Adolphe Basler and Ernest Brummer, L'Art précolombien, Paris 1928, pl.61

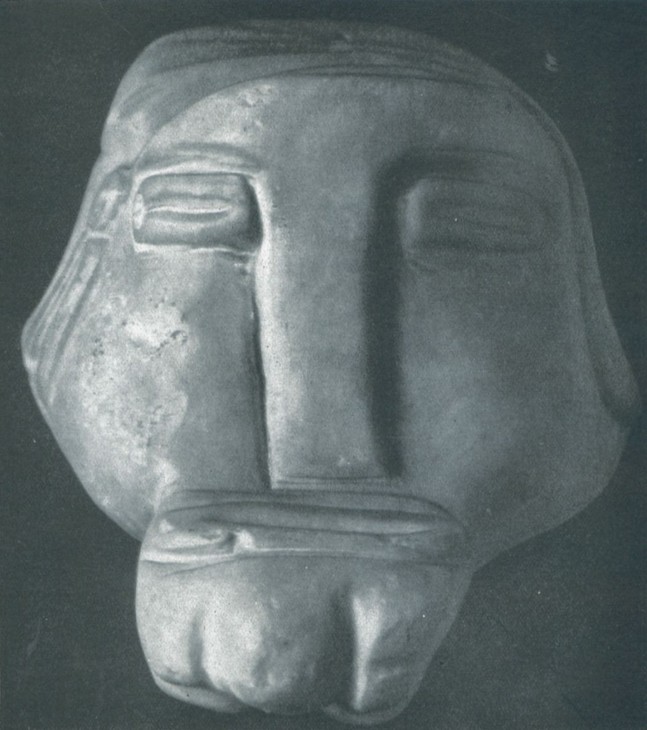

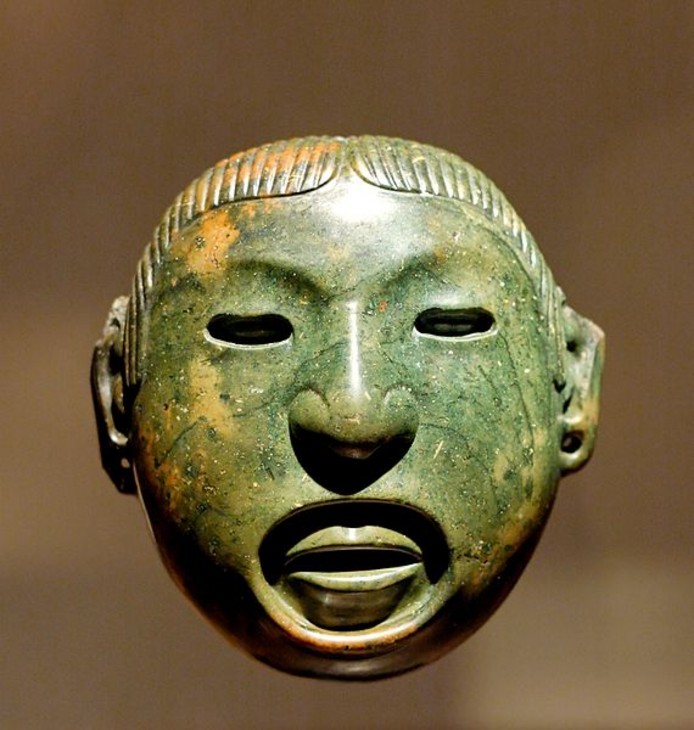

Xipe Totec mask from Mexico (possibly nineteenth century)

210 x 245 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.5

Xipe Totec mask from Mexico (possibly nineteenth century)

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Following his first Mask of 1924 Moore made two mask sculptures in 1927 before making a further nine mask sculptures between 1928 and 1930. According to Wilkinson, the acceleration in production of masks ‘may well have been stimulated’ by Moore’s acquisition in 1928 of Adolphe Basler and Ernest Brummer’s book L’Art précolombien (1928).21 As well as containing an essay (written in French) outlining the different characteristics of pre-Columbian sculpture from across the Americas and highlighting key architectural sites, the book was heavily illustrated. In addition to photographs depicting Mayan figure sculptures and Peruvian pottery, the book also contained over thirty plates of ancient Aztec masks in the collections of the British Museum in London and the Musée de Trocadéro in Paris.22 It is probable that in carving Mask 1928 Moore amalgamated a number of features found in different ancient examples. The round, widely spaced eyes in his mask, for example, may have been inspired by the equally widely spaced and pierced eyes of the mask tentatively identified in Basler and Brummer’s book as coming from the Nass River region of northern British Columbia, Canada (fig.4), though the relative flatness of Moore’s sculpture differentiates it from this curved mask. Also illustrated in L’Art précolombien, the British Museum’s Xipe Totec mask (fig.5) has an open round mouth and pierced ear lobes. In 1981 Moore included this Xipe Totec mask in his photographic book Henry Moore at the British Museum, in which he identified and discussed artworks from the British Museum’s collection that influenced him during his career. He explained in the book how the holes of this mask ‘make a formal contrast to the solid part of the sculpture’.23 Although Moore would not fully explore the aesthetic qualities of holes in his stone sculptures until the 1930s, his Mask is an early example of how he began to challenge conventional notions of the solidity of sculpture.

Aztec mask of Xipe Totec from Oaxaca, Mexico before 1521

110 mm

Musée du Louvre

reproduced in Adolphe Basler and Ernest Brummer, L'Art précolombien, Paris 1928, pl.49

Fig.6

Aztec mask of Xipe Totec from Oaxaca, Mexico before 1521

Musée du Louvre

reproduced in Adolphe Basler and Ernest Brummer, L'Art précolombien, Paris 1928, pl.49

Henry Moore

Head of a Woman 1926

Concrete

The Hepworth Wakefield

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Norman Taylor

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Head of a Woman 1926

The Hepworth Wakefield

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Norman Taylor

I used the asymmetrical principle in which one eye is quite different from the other, and the mouth is at an angle bringing back the balance. I had noticed this in some of the Mexican masks, and I began to find it in reality in all faces ... it is when you come to look at a person’s face with acute observation that you will find these many small variations that make all the difference between a really sensitive portrait and a dull one.26

While in his later work Moore would avoid representing personalised facial expressions so that his figures could stand as universal archetypes, in Mask the face seems to convey a certain youthful vulnerability and even alarm.

Raymond Coxon and Edna Ginesi

Raymond Coxon (1896–1997) was identified as the owner of Mask when it was first exhibited in Moore’s 1951 solo exhibition at the Tate Gallery, curated by David Sylvester. Moore had met Coxon, a painter, on his first day at Leeds School of Art in 1919 and they became close friends. Together, and with fellow Leeds artists Barbara Hepworth and Edna Ginesi, they went on to study at the RCA where the four were known as the ‘Leeds table’.29 Moore and Coxon shared accommodation in Chelsea as students and it was Coxon who accompanied Moore on his first trip to Paris in 1922.30 Coxon and Ginesi married in 1926 and Moore was their best man; his wedding gift to them was his sculpture Head of the Virgin after Rosselli 1922–3. Coxon later taught at the Richmond College of Art where, in 1927–8, his students included the painter John Piper. Both Coxon and Ginesi taught at Chelsea Polytechnic throughout the 1940s and 1950s and examples of their work are held in Tate’s collection.31

Given their close friendship it is probable that Coxon acquired Mask directly from the artist shortly after it was made. In May 1964 Coxon and Ginesi wrote a letter to Moore stating:

A man from Paris has written to borrow the mask for an exhibition of Primitive Influences and this happens to coincide with a letter from Gowing giving us the congé from Chelsea.

It has brought about a situation where we must reorganise our financial position and we are turning our much loved possessions into negotiable assets.

So we have replied to Paris regretting that his request may have to be passed on to a new owner.

It is not painless to dispose of things we have loved for up to forty years, it goes without saying.32

It seems that, having taught at Chelsea Polytechnic for more than twenty years, both Coxon and Ginesi were made redundant when the School of Art merged with the Regent Street Polytechnic School of Art to create the new Chelsea School of Art (the first head of this new institution was the artist and writer Lawrence Gowing). The loss of their salaries obliged them to sell Moore’s work.

In 1966 Mask was exhibited at the commercial gallery Marlborough Fine Art, which was at this time Moore’s primary London dealer. It is likely that Moore advised Coxon on where he could sell the sculpture, and Marlborough would have been an obvious choice (Mask had previously been loaned to Marlborough in 1961 for its exhibition of Moore’s stone and wood carvings). Coxon sold the sculpture to Marlborough Fine Art on 24 June 1964 and it was bought from the gallery two years later by the British businessman Sir Alistair McAlpine. McAlpine sold the sculpture at Sotheby’s and although the date of the sale is currently unknown, it is likely that the sculpture was not in his possession for long. Mrs Lewis Cohen acquired the sculpture at auction, and it remained in her collection for around thirty years. Mask was purchased from this private collection through Browse and Darby, London, with assistance from the National Art Collections Fund, by Tate in 1993.

Alice Correia

December 2012

Notes

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, 1957, 5th edition, London 1988, p.2.

For example, see Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.72; Henry Moore: Early Carvings 1920–1940, exhibition catalogue, Leeds City Art Galleries, Leeds 1982, p.62; Andrew Causey, The Drawings of Henry Moore, London 2010, p.34. In the 2010 Moore exhibition at Tate Britain this sculpture was displayed in the room titled ‘World Cultures’; see http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/henry-moore-0/henry-moore-room-guide/henry-moore-room-guide-room-1 , accessed 22 November 2012. The term ‘pre-Columbian’ denotes the period of history preceeding Christopher Columbus’s voyages to South America in 1492 and European contact with and influence on American indigenous cultures and civilisations.

For example, the French artist Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) took inspiration from ancient Peruvian pottery for his figurative ceramic works in the 1880s, a precedent of which Moore was certainly aware by the time he carved Mask; see Braun 2000, pp.74–5.

Christopher Green, ‘Expanding the Canon: Roger Fry’s Evaluations of the “Civilized” and the “Savage”’, in Christopher Green (ed.), Art Made Modern: Roger Fry's Vision of Art, exhibition catalogue, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London 1999, p.126.

Henry Moore, ‘Primitive Art’, Listener, 24 April 1941, pp.589–9, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.104.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeny, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.45.

Alfred P. Maudslay specialised in the study of ancient Mayan inscriptions and his collection of Mayan sculptures had been kept in the basement of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, until ethnographic curator Thomas Joyce transferred it to the British Museum and dedicated a room in the museum for its display. See Braun 2000, p.95.

For reports on these excavations see Anon., ‘Ruins in British Honduras’, Times, 12 January 1926, p.11, and Anon., ‘More Mayan Ruins Discovered’, Times, 10 February 1926, p.13.

This link between the photographic reproduction and the sketch is asserted in Alan Wilkinson, ‘Circus Drawings and Study of a Mexican Head’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore, London 2006, p.99.

Alan Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.68.

Henry Moore, Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981, p.74. Although scholarship undertaken at the British Museum has suggested that the Xipe Totec mask might date from the nineteenth century and had been created to satisfy the growing European market for antiquities, it nonetheless remains important for understanding the development of Moore’s sculpture; see http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aoa/m/masks_of_xipe_totec.aspx , accessed 23 November 2012.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and Direct Carving: Technique, Concept, Context Sarah Victoria Turner

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore and Stone: Methods and Materials Sebastiano Barassi and James Copper

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Mask ?1928 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www