At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee

Julia Kelly

Moore served as trustee of the Tate Gallery twice (1941–8 and 1949–56) and also of the National Gallery (1955–74). This essay looks at some of the decisions he was involved in making and considers how these roles impacted on the development of his career and identity as an artist.

Photograph showing the Trustees of the National Gallery in the Conservation Studio 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Douglas Glass, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Photograph showing the Trustees of the National Gallery in the Conservation Studio 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Douglas Glass, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The Moore family on the lawn behind Hoglands having an informal tea party with Philip and Cicely Hendy early 1950s

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Photo: Sue Turner, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

The Moore family on the lawn behind Hoglands having an informal tea party with Philip and Cicely Hendy early 1950s

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Photo: Sue Turner, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Nevertheless, Moore also held himself at a certain distance from the upper echelons of the art world. His letter turning down his knighthood reflected a certain ‘them and us’ mentality. Moore seemingly did not want to mark himself out from other artists: ‘such a title might tend to cut me off from fellow artists whose work has aims similar to mine’. He also cited the altered conception of his identity and work that the title would bring about and which he was keen to avoid, suggesting that such official honours were not in keeping with his artistic vision. (‘I have been trying to consider how I myself should feel if I were addressed as “Sir Henry”, every day, even in my workshop, and I cannot help thinking that it would somehow change my conception of myself and with it the conception of my work.’)9 Moreover, Moore may have been a Trustee of two central British art institutions but he was apparently not wholly ‘art establishment’ material. Writing in his autobiography in the 1960s John Rothenstein, director of the Tate and Moore’s supporter, made the striking comment that ‘figures such as Moore, Kokoschka and Bacon are hardly imaginable as Academicians’.10 Rothenstein’s comment was in the context of a wider discussion about the shifting spheres of influence in the art world after the Second World War, where an older Royal Academy-dominated ‘establishment’ had made way for a newer one formed of the Tate, ICA, British Council, Arts Council and Contemporary Arts Society.11

Why Moore would be unimaginable as an RA to Rothenstein is unclear but he was probably viewed as the antithesis of the then President of the Royal Academy, Charles Wheeler, the first sculptor to take up the post. In his later recollections Caro, who had trained under both artists, certainly played up the contrast: he recalled the ‘Victorian academy pointing machine’ he had used in Wheeler’s studio, whose results were ‘totally mechanical, awful!’, and whose use Moore deliberately avoided.12 Wheeler had served on the Tate’s Board of Trustees between 1941 and 1949, at the same time as Moore, and Moore was also on the committee that selected sculptures including Wheeler’s for the Battersea Park Open Air Sculpture Exhibition in 1948.13 Were the lines of demarcation between rear- and vanguards still so clearly drawn in the 1950s and 1960s? John Russell, in his account of Moore’s life and work first published in 1968, remembered a time in the past when a historian of British sculpture had warned against confusing Moore with ‘Henry Moore R.A.’, a Victorian artist in the Tate’s collection: the implication of this recollection was that now there was no reason why the modernist Moore should not also be admitted to the Academy.14 Perhaps Rothenstein’s comment reflected Moore’s own hostility towards the Royal Academy, which was rooted in the scandal over the partial demolition of Epstein’s sculptures on the Strand in the late 1930s, and was fuelled by Alfred Munnings’s public attacks on Moore in the late 1940s (a well known painter of horses, Munnings was an outspoken enemy of modernism).15

Moore’s own career underwent a startling progression during the war years, which coincided with the beginning of his Trusteeship at the Tate, and his involvement with the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA), alongside Kenneth Clark (then Director of the National Gallery), Philip James (who would later edit Moore’s writings), Hendy and Rothenstein. As Packer put it, by the end of the war, ‘at forty-seven, the wilful iconoclast, unremitting modernist and enfant terrible of the popular imagination was translated by a curious social alchemy into a substantial, senior and eminently respectable public figure’.16 Not only that, but Moore came to apparently enjoy his role on various boards, and be seen as a desirable addition to them, as Russell suggested: ‘Not to have Moore on a committee meant, in official art circles, the loss of a leaven of good nature and good sense’.17

Moore’s relationship with Tate was also transformed during the 1940s, setting the scene for a sustained connection between the artist and the institution which culminated in Moore’s gift to the Tate of thirty-six bronzes and plasters in 1978, a collection of works which complemented the gallery’s existing holdings, some of which had been acquired with Moore’s help at reduced prices. In addition, Moore began to give Tate in the mid-1970s a substantial collection of his prints, with the intention of the gallery eventually owning one copy of each impression of his graphic output (over 700 works in total). It might be useful to compare Moore’s representation at Tate with that of another prominent British sculptor of the pre- and post-war period, Frank Dobson. In 1938 Dobson had six sculptures in Tate’s collection; Moore had none. By 1968, when Moore’s second solo exhibition was staged at Tate, he was represented by twenty-one sculptures and fifteen drawings; Dobson’s tally had risen only by a further four to ten works.18 Tate’s holdings of Moore’s work would have been even higher were in not for a sequence of events in the late 1960s and early 1970s which saw a large number of original plasters as well as sculptures and works on paper being donated to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto instead of finding a home in London.19

This essay will examine Moore’s changing public status, and relationship with the Tate above all, through his official activity as a Trustee of the two major British national art galleries. It uses the available evidence from minutes of committee meetings, as well as other archival sources, to piece together a picture of Moore’s involvement, as part of his overall professional concerns as an artist and broader artistic identity. The sculptor’s attitude towards the Tate, as one of the institutions that would most prominently represent him in Britain, was also not without its ambivalences: having ‘conquered’ the gallery initially, Moore’s ambitions would later take him elsewhere into an international arena. Arguably, his vision for his own work was from the outset a universalising one, taking its bearings from the wide scope of the British Museum and a sense of a long artistic tradition into which he could insert himself. He might have been paired with Turner for the Venice Biennale in 1948, a great honour as a modern ‘master’, but ultimately Moore looked to ancient Mexico, or the Michelangelo of the Carrara quarries. First, however, he would have to find acceptance within his national context, via the Tate Gallery.

Moore and the Rothensteins

In the late 1930s the then director of the Tate Gallery, the painter James Bolivar Manson, was supposed to have notoriously declared that Henry Moore’s work would never enter the gallery’s collection (if it did, it would be ‘over my dead body’, he is reported to have said).20 While Manson’s attitude towards Moore’s work seems to indicate a clearly held antipathy towards modernist art, the reality of this was probably more complex. In 1938 Manson was also involved in advising the customs authorities about the importation into Britain of a group of sculptures by artists including Arp, Brancusi, Calder and Laurens, on their way to an exhibition organised by the collector Peggy Guggenheim. Manson gave his opinion that these works were not art, effectively blocking their entry into the country and apparently scuppering the exhibition. But he changed this assessment under pressure from art critics and artists, including Moore, who published statements in the press defending the work of these significant international artists.21 This incident was reminiscent of the famous trial in New York a decade earlier when Brancusi’s work had been examined and finally judged to be art, with the help of witnesses including Duchamp and Jacob Epstein. Manson was, in fact, a good friend of Epstein, having shared a studio with him in Paris in the early 1900s while they were both studying at the Académie Julian. Manson supported Epstein in one of his controversies over public works, the planned removal of his reliefs from the headquarters of the BMA building in the Strand in 1935, adding his signature to a letter to the Times which was co-signed by William Rothenstein and Kenneth Clark, among others.22 However, the distrust of modernism was palpable and prevented the gallery from considering the work of Moore and other leading British modernists under Manson’s directorship.

Attitudes towards Moore’s work at the Tate changed when John Rothenstein took over as director in 1938. In the following year the Board of Trustees voted finally to accept the gift of Moore’s Recumbent Figure 1938 (Tate N05387) from the Contemporary Art Society, which had been ‘on hold’, the first work by Moore to enter the national collection. By August 1940 Rothenstein was writing to Moore to confirm Tate’s purchase of three drawings from Moore, and expressing the wish to acquire more work.23 Rothenstein later recalled in his autobiography that Moore was not making sculpture at the time due to the ‘restlessness and tension’ of the time, instead experimenting with using watercolour washes over white wax crayon, where the initial use of wax to suggest forms was for Rothenstein analogous to his previous practice of direct carving.24 It seems significant that Rothenstein was keen to connect these drawings closely to Moore’s sculpture, as if they could stand in for it at a difficult time during the war. In May 1941 Moore was officially welcomed onto the Board of the Tate Gallery’s Trustees, to replace the painter Augustus John, who had served there between 1933 and 1941. (John had purchased work, probably drawings, from Moore’s first solo exhibition at the Warren gallery in January 1928, and was included in a group show with Moore that travelled to Berlin later that spring.)25

Attitudes towards Moore’s work at the Tate changed when John Rothenstein took over as director in 1938. In the following year the Board of Trustees voted finally to accept the gift of Moore’s Recumbent Figure 1938 (Tate N05387) from the Contemporary Art Society, which had been ‘on hold’, the first work by Moore to enter the national collection. By August 1940 Rothenstein was writing to Moore to confirm Tate’s purchase of three drawings from Moore, and expressing the wish to acquire more work.23 Rothenstein later recalled in his autobiography that Moore was not making sculpture at the time due to the ‘restlessness and tension’ of the time, instead experimenting with using watercolour washes over white wax crayon, where the initial use of wax to suggest forms was for Rothenstein analogous to his previous practice of direct carving.24 It seems significant that Rothenstein was keen to connect these drawings closely to Moore’s sculpture, as if they could stand in for it at a difficult time during the war. In May 1941 Moore was officially welcomed onto the Board of the Tate Gallery’s Trustees, to replace the painter Augustus John, who had served there between 1933 and 1941. (John had purchased work, probably drawings, from Moore’s first solo exhibition at the Warren gallery in January 1928, and was included in a group show with Moore that travelled to Berlin later that spring.)25

Moore’s apparently rapid ascendency within the Tate, moving from persona non grata to Board member, belied a network of contacts and supporters that predated this moment. Most significant within these was probably John Rothenstein’s father William Rothenstein, a painter who had trained in Paris at the Académie Julian in the 1890s. An important supporter of the Camden Town Group, he became Principal of the Royal College of Art (RCA) in 1920. Moore began as a student at the RCA in 1921, and in 1924 took up a part-time teaching post there. Being at the RCA also apparently facilitated his entrée into London society, with Rothenstein’s encouragement. Moore recalled meeting the future prime minister Ramsay McDonald, among other eminent public figures, at William Rothenstein’s house in Kensington, and being put at his ease: ‘I wasn’t awed or anything; and so Rothenstein gave me the feeling that there was no barrier, no limit to what a young provincial student could get to be and do’.26 Moore shared with Rothenstein a background in the North of England, away from the capital, and a certain outsider status: Rothenstein as the child of German-Jewish immigrants to Bradford in the 1860s; Moore as the seventh son of a coalminer in Castleford. According to Moore’s account, Rothenstein encouraged and promoted his confidence, telling him ‘Moore, you’ve got the ball at your feet’.27 Rothenstein’s support for Moore was later repaid, when Moore was instrumental in pushing through the acquisition of paintings by him as a Tate Trustee.28

William Rothenstein’s brothers Charles and Albert Rutherston (who Anglicised their names) were also important early supporters of Moore. Charles was probably responsible for Moore’s first sales of his work, buying two wood carvings in c.1923.29 He also introduced Moore to the gallery owner Dorothy Warren, who staged the sculptor’s first solo exhibition in January 1928 at the Warren Gallery in London.30 Albert Rutherston (1881–1953) was a painter associated with the Camden Town Group who became Ruskin Master of Drawing in Oxford in 1929.31 In November 1938 he opened the South West Riding Artists’ Exhibition in Wakefield, in which Moore’s Reclining Figure was displayed (and subsequently acquired by Wakefield Art Gallery in 1942, after several years of negotiation).32 Rutherston was also a close friend of Augustus John, whom Moore replaced as a Tate Trustee in 1941.

The ideal trustee

It seems that William Rothenstein’s son John had already been aware of Moore’s work while in Leeds, where he directed the Art Gallery between 1932 and 1933. In unpublished notes on Moore in the Tate archive from the early 1930s, written on the back of paper headed ‘City Art Gallery, Leeds’, John Rothenstein claimed that he had got to know the artist ‘not long after his arrival’ at the Royal College, having had ‘many opportunities of getting to know the students’ since his father took over as Principal in 1920. In these notes Rothenstein saw Moore as part of a ‘loosely knit and greatly talented group’, which numbered seven Yorkshiremen among them, ‘either by birth or adoption’.33 The dynamic between capital and province being alluded to here is surely significant, mirroring the Rothenstein family’s own career progressions, as well as their perception that talented Yorkshire artists could only flourish by moving to London.34

In his autobiography John Rothenstein recalled his first impressions of the Tate’s Board of Trustees, describing their meetings as ‘seignorial in tone, dominated by aristocratic connoisseurs and men of affairs’. An artist, however, could serve a different role, and Rothenstein had a more favourable memory of Moore’s predecessor, Augustus John: ‘All listened with deference, however, to the sensible, simply expressed opinions of Augustus John’. Other artists on the board such as William Nicholson and Walter Russell left little impression, but the only sculptor represented, Sir William Reid Dick, was notable for the wrong reasons, being ‘apt to take a conventional “Royal Academy” line very much out of harmony with the sentiments of his fellow-Trustees’.35

The appointment of Reid Dick to the Tate Board of Trustees in 1934 had been made partly under pressure from the Royal Society of British Sculptors (RBS), who protested when, in 1928, a painter filled a vacancy on the board created by the death of the architectural sculptor Henry Poole.36 Reid Dick represented, then, the interests of not only the RBS but also those of the Royal Academy (of which he was a member), which supported the former organisation in a number of complaints made against the representation of British sculptors in the Tate’s galleries in the late 1930s.37 This quasi-feud was particularly focused on the new Duveen Gallery, which had been designed especially to display sculpture, and had opened in 1937. John Rothenstein recalled a delegation from the RBS coming to the Tate to protest at the lack of British sculpture shown in the new Sculpture Hall.38

Moore’s status as a sculptor in particular, as well as a modern artist of a certain tendency (not allied to the ‘conservative’ strand of the Royal Academy) was undoubtedly significant in his appointment as a Tate Trustee. If ‘progressive’ continental and British sculpture was needed to fill the new Duveen Gallery, then to secure the input and validation of one of its leading protagonists was surely crucial. Importantly for this role, however, Moore was a good ‘compromise’ candidate: neither too radical nor too backward-looking, aligned with no particular grouping, although having connections with both abstract and surrealist groups in the 1930s. Moreover, Moore had other influential supporters during the late 1930s and early 1940s in the form of Clark and Hendy. They both admired the old masters and modern art and their promotion of certain British artists (Moore, Graham Sutherland and John Piper, for instance, who were shown together at Temple Newsam in Leeds in 1941) began to grant the latter the status of modern masters. As the then director of the National Gallery Clark’s support was particularly significant: he appointed Moore an Official War Artist in 1940 and and promoted Moore through the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, including the latter’s Shelter drawings in the exhibition of National War Pictures at the National Gallery in 1941–2. This proved a pivotal moment in the history of the public’s perception of Moore. Clark’s role as an arbiter of taste in old master works may well have encouraged Moore to think of himself in these terms too.39

In the references made by John Rothenstein to Moore’s appointment as a Trustee in his autobiography, three main aspects of the Yorkshireman’s suitability can be noted: his personal qualities and character; his identity as a London museum-goer; and his status as a practising artist. The kinds of personal qualities to which Rothenstein referred include an ‘air of unhurried confidence’ and a ‘good conscience’, as well as a constancy of behaviour and approach: ‘the same Yorkshire hard-headedness tempered by a reluctance to think ill of his fellow-men without manifest cause’.40 As well as playing up certain stereotypes relating to Moore’s background, the Tate’s director also described the artist as ‘the happiest man I knew’.41 In an article on Moore for the Times Saturday Review written in 1968 by Hendy, who would be Director of the National Gallery during the artist’s Trusteeship in the 1950s and 1960s, he was portrayed as eminently sociable and public-spirited: ‘The fact that he finds in committee work that contact with others which his love of people in quantity demands, as well as a chance to further significant causes, has been a piece of good fortune, for post-war misanthropic England’.42

Rothenstein recalled his impressions of Moore as his Hampstead neighbour in the late 1930s in his autobiography:

He used to encourage me to talk about my hopes for the Tate ... and he would listen with alert and benevolent interest. Although an impassioned visitor to museums and art galleries, he seemed to have given little thought to the possibility of their representing his own generation. (He himself, for instance, was still unrepresented at the Tate at the time of my first visit.) The warmth and perceptiveness of his response to my hopes for securing such representation at the Tate determined me to do what I could to procure his appointment as a Trustee43

This perception of Moore as a committed museum-goer may well have been informed by his father William’s interactions with Moore while at the RCA, in particular by the letter that Moore wrote to Rothenstein senior from Italy while on his travelling scholarship in 1924, in which he appeared relatively unimpressed by the cultural offerings of Paris and Italian cities: ‘If this scholarship does nothing else for me – it will have made me realise what treasures we have in England – what a paradise the British Museum is, and how high in quality, representative, how choice is our National Collection’.44

As an artist, Moore could fulfil a particular function as a Trustee. For Rothenstein, he strengthened the conviction that artists had a significant part to play on the gallery’s Board.45 This was not just in themselves, but as conduits to the work of other fellow artists: ‘It was not that I considered artists to be necessarily the best judges of painting and sculpture in general, but they are the best judges of the kind of painting and sculpture which they themselves practise. Since the emerging generation now needed to be represented, what better judges than such leading figures among them?’46

When Moore became a Trustee at the National Gallery in the mid-1950s, however, his expertise was being sought as an artist who precisely could pass judgment on art made before his time, notably, the work of French Impressionists like Renoir and Degas whose reputations were being consolidated during this period. Hendy in his appraisal of Moore’s role as a Trustee pointed to the then recently published statement on Renoir included in Philip James’s anthology of Moore’s writings and statements, and recalled the artist’s role as a commentator on the work of fellow-artists more broadly: ‘To every kind of work of art his reaction is quick and generous, coming from a sympathetic understanding of what the artist was trying to do’.47 Hendy’s article also implied the drawbacks of the practically-minded artist, recalling Moore’s ‘natural unwillingness to do much preparation’ for the National Gallery’s board meetings. Moore’s strengths as a committee member lay for this commentator in his artistic insights, despite a certain lack of engagement with official business: ‘I occasionally had to beg him to read the minutes or the agenda during his train journey. It would have been no use to ask for his vote – nor was there any need. His view on affairs is usually the practical one; his comments on artistic matters are awaited by all concerned as for a revelation’.48 While Rothenstein’s accounts of Moore as a Trustee are generally flattering, a reference to the comparative strengths of Moore and Coldstream (who served as a Tate Trustee between 1949 and 1963) is revealing: ‘The opinions of the Trustees ... especially Henry Moore’s, carried weight, but none of them ... was a professional committee man as Coldstream was: a master of the art of persuasion, quick, supple, courteous – and determined’.49

Ultimately, if we read between the lines of Rothenstein’s account, one of the functions of Moore as a Tate Trustee was to secure his own work for the Gallery’s collection, an arrangement of benefit to both sides. One of his extended encomiums of Moore as a Trustee suggests precisely this:

To the inspired commonsense of Henry Moore I had frequent recourse, especially where the acquisition and even, on occasion, the placing of sculpture was concerned. During my years as Director almost all the Trustees formed an attachment to the Tate, but with Henry the attachment was a deep and personal one: even after he had completed his second term as Trustee he continued to identify himself closely with our affairs. ‘I think we ought to have that,’ he would say about some proffered gift or loan that I had mentioned to him. Later still, when it was decided to represent certain artists as fully as our resources allowed, he showed great generosity in enabling us to acquire outstanding examples of his own work at minimal cost.50

The sculptor speaks

Moore’s contributions to Board meetings, as recorded in their minutes, show overall an increase in confidence during the thirty or so years of service he provided at the Tate and the National Gallery, as is to be expected. This is also reflected in the transition from his role as a Tate Trustee, where primarily at least he was expected to pass judgment on the work of his peers, to his role at the National, where his advice on acquisitions of works by major historical artists was sought. Moore’s guidance on artistic matters was looked to even during the brief breaks in his Trusteeships: in the minutes of the May 1948 meeting a letter of thanks to him was proposed as his tenure had come to an end, but with a ‘hope that he would re-join the Board before long’.51 The following month, in June 1948, a proposal to take on an exhibition of contemporary Italian painting which had been organised at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, by Alfred Barr was endorsed indirectly by Moore as a non-Board member: ‘The chairman mentioned that Mr Henry Moore was especially enthusiastic about the recent achievement of Italian artists and the Board agreed in principle that it would be most desirable to hold such an exhibition’.52 After his tenure ceased definitively in 1956 he was occasionally mentioned in meetings as a continuing point of reference, and continued to correspond with John Rothenstein and Norman Reid about Tate matters.

It is interesting to speculate about the significance of Moore’s status as a sculptor in particular when he joined the Tate Board, especially in the context of the recently-opened Duveen gallery. The composition of the Trustees for Moore’s first meeting on 20 May 1941 was as follows: Sir Edward Marsh, Lord Sandwich, Sir William Reid Dick, Allan Gwynne-Jones, Lord Methuen, Jasper Ridley, Kenneth Clark, Moore and Lord Crawford (absent at Moore’s first meeting). Only three of those on the Board were artists: Reid Dick, whose role has been discussed already, Gwynne-Jones, who had been Professor of Painting at the RCA during William Rothenstein’s directorship, and Moore. Reid Dick would soon stand down, to be replaced in 1942 by Charles Wheeler. When Wheeler was replaced by Moore in 1949, to take on his second stint as a Tate Trustee, there were more artists represented on the Board, but all painters: William Coldstream, Graham Sutherland, John Piper and Henry Lamb. A letter in the Tate archive from Jasper Ridley, Chair of the Board of Trustees to Anthony Bevir, Clement Attlee’s Private Secretary in July 1949, made the case for Moore’s reappointment:

I have reflected further on this question of a sculptor to take the place of Charles Wheeler on the Tate Board. It is not very easy because the sculptors whom we would care to have are not very thick on the ground. In any case, Henry Moore was a conspicuously useful Trustee on any topic that arose, whether of judgment or administration, and I have no doubt that he would be the most agreeable person.53

The question of why sculptors ‘whom we would care to have’ were so scarce is a tantalising one, and suggests again Moore’s particular qualities in bridging different artistic and institutional worlds. By the 1950s Moore was the sole sculpture representative on the Tate Board, and his opinion was sought accordingly.

The year before Moore joined the Board, one of the minutes of John Rothenstein’s contributions notes his recent visit to the U.S.: ‘I took every opportunity of bringing the special qualities of Contemporary British Art, and Sculpture, to the notice of the general public, of connoisseurs, and more especially that of the directors of American Museums’.54 It is of note here that Rothenstein includes ‘sculpture’ as a specific category (and does not refer to ‘painting’ by contrast, but more generally to ‘contemporary art’). Of course, Moore was already on the radar of Alfred Barr, having featured in his exhibitions Cubism and Abstract Art and Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism in 1936. But given the way in which Rothenstein began to bring first Moore’s work into the Tate, then the sculptor himself as Board member, it is tempting to see his presence behind the heightened profile of sculpture, and particularly contemporary sculpture, for the Tate’s director.

A push to enrich the Gallery’s sculpture holdings, however, could not be immediately forthcoming during the war years, as a memorandum on purchasing policy aired at a meeting in December 1942 made clear. Under ‘Sculpture’, the need to purchase more contemporary sculptural works was recognised but the challenge this posed was also noted: ‘it would appear that war conditions have played an important part in limiting the production of sculpture in this country’.55 As we have already seen, Rothenstein had already been active in acquiring drawings by Moore to ‘stand in’ for his sculptures, and another statement from the same meeting confirmed an agreement between Tate and the War Artists Advisory Committee to include in the Tate’s collection some of the war works arising from that initiative; a series of Moore’s Shelter Drawings were presented to the Tate in 1946.56

In a meeting of January 1945, at which Moore was present, the Board considered and declined the purchase of a work in wood by Barbara Hepworth titled simply Sculpture for 90 guineas. The case prompted consideration of the representation of similar work in the collection: ‘It was felt, however, that there was a case for some representation at the Gallery, of ‘abstract’ art (of which the carving under consideration was an example), and it was agreed to consider this question more fully at the next meeting’.57 At the February 1945 meeting, the role of ‘modern foreign art’ was up for discussion: ‘A list of foreign painters and sculptors ... either insufficiently or not at all represented at the Tate was shown to the Board, who agreed that the gaps in the collection were grave’.58 The list of sculptors included the following names: Arp, Barlach, Bourdelle, Brancusi, Calder, De Fiori, Flanagan, Gabo, Gargallo, Giacometti, Kolbe, Laurens, Lehmbruck, Lipchitz, and Zadkine. Another complementary ‘must-have’ list of makers of ‘Abstract Art’ included a sizable proportion of sculptors: Arp, Bigge, Brancusi, Calder, Gabo, Giacometti, Hepworth, Miró, Mondrian, Moholy-Nagy, Moore, Ben Nicholson, Ozenfant, Pevsner, Piper, and Tunnard. The sculptors listed here are largely expected names, with the exception of the Austrian sculptor Ernesto de Fiori and a mysterious ‘Flanagan’.59 Moore himself was of course present in the second list of ‘abstract’ artists, and the acquisition of his sculpture (rather than works on paper) by Tate recommenced that year, with the minutes of the April 1945 meeting recording the decision to purchase four bronzes relating to his Northampton Madonna and Child and three relating to The Family (for the Barclay school in Stevenage).60

During the 1940s, while Moore himself did not contribute very frequently to the Board’s discussions, questions relating to his own work did arise. His Green Hornton stone Recumbent Figure 1938 (Tate N05387), which the Tate had acquired and which had gone on loan to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, had been displayed outside and was then damaged, ‘knocked off its pedestal and its head severed by two ill-disposed persons who had entered the Museum premises’, as the Board minutes recorded it.61 Its subsequent repair and the compensation paid to the Tate for its damage were also raised.62 Moore was not always present at the meetings where these matters were discussed (and he withdrew when the purchase of his work arose). On occasion he communicated his views to the Board at a distance. In the Tate archive of Trustees’ correspondence one postcard dated May 1941 and sent from Hoglands to Rothenstein reads: ‘I vote for the late Gertler – I think his later period should be represented in the Gallery./I do NOT vote for the A.R. Thomson’.63 Another of unclear date (probably from the 1950s) reads simply, ‘I think, definitely, we should have a Calder mobile/Henry’.64

Art adviser and intermediary

Moore was certainly much more actively involved in potential acquisitions during the 1950s and played a more prominent role as a supporter of artists of his own and younger generations. In 1947 Moore had already shown his support for a recently deceased fellow artist, Paul Nash, with whom Moore had collaborated in the group Unit One in the 1930s, lending his voice to the idea of a memorial exhibition: ‘Mr Henry Moore stressed the desirability of holding memorial exhibitions of outstanding artists, and the Board reaffirmed that the organisation of such exhibitions would be regarded as part of the Gallery policy’.65 Similarly, a minute of February 1950 recorded that ‘Mr. Moore proposed and the Board agreed that the Tate should organise a Memorial Exhibition of the work of Edward Wadsworth which could perhaps be shown in the autumn’.66 The following year Moore also championed the cause of an ailing Wyndham Lewis, who, as he put it, ‘has recently been afflicted by almost complete loss of sight, and whose services as an art critic, writer and artist were outstanding. He wondered if there were any way in which it could be recommended that this distinguished critic could be assisted by the State, preferably by being put on the Civil List’.67 Moore’s advocacy of artists whose careers had finished went in tandem with his ongoing support for the increased representation of younger artists in general at the Tate. In March 1950 he joined fellow Trustee Graham Sutherland in suggesting ‘that the Tate could concern itself to a greater extent with the work of living artists’.68 In a meeting of September 1952 the Board was read a letter from the absent Trustee Dennis Proctor (a Secretary at the Treasury), expressing his unease about some of the younger artists being brought forward for consideration, and suggesting that ‘the Board should be specially careful about buying works by favourite pupils known to them’ (a reference probably aimed at Coldstream who sometimes promoted the work of those he had taught).69 The chair, Earl Jowitt (then Lord Chancellor), overruled this, however, with Moore waiting in the wings to reinforce the point: ‘Lord Jowitt agreed that, while not being too experimental in their choice, it was the policy of the Gallery to consider the work of artists while they were still young. Mr. Moore thought that de Stael and Soulages should be represented, and the Board agreed to consider a painting by Soulages at the next meeting, if possible’.70

Moore’s contributions to Board meetings and interactions with the Tate often concerned considerations of what works to purchase by what artists. It seems that Moore’s judgement was most often trusted in this respect, and his advice followed. In January 1951 the minutes recorded just such an intervention: ‘Mr. Henry Moore reported that an interesting painting by George Lambert was to be sold at Christies’ the following day. After consideration the Board empowered Professor Coldstream to bid on its behalf at the sale of this work up to £160’, and the gallery duly purchased Lambert’s A View of Box Hill, Surrey 1733.71 However, another potential purchase of a work by Alexander Calder, in which Moore was involved and which was raised at the same Board meeting, did not materialise: ‘The Board, after considering “Forest” (mobile) by Alexander Calder, asked Mr. Henry Moore and Mr. John Piper to select two other examples from the Exhibition at the Lefevre Gallery for consideration at the next meeting’.72

Moore was involved in some of the major early twentieth-century sculptural acquisitions at the Tate during this period, including the purchase of works by Matisse. In July 1952 at the Trustees’ meeting sculptures by Matisse were considered using photographs, and opinions were divided as to whether a sculpture or a painting were preferable:

Sir Philip Hendy said that much as he would like to see an example of Matisse’s sculpture in the Gallery, he thought this artist was not sufficiently well represented as a painter, and would much prefer a monumental example of his work in this medium. Mr Sutherland suggested that such a work should not be later than 1918–23. Mr. Moore thought that both a sculpture and further examples of painting by Matisse should be sought. Sir Philip Hendy felt that if we were to buy both, the money available for a painting would be insufficient to acquire a really first rate example.73

A small bronze by Matisse, Reclining Nude II 1927 (Tate N06146) was purchased in 1953 using the Knapping Fund, suggesting that Moore was at least partially successful in getting his wish. In 1955 the question of acquiring Matisse’s Backs (Tate T00081, T00114, T00160 and T00082) from the late artist’s family arose (Matisse had died in 1954). Moore, along with Piper and Lawrence Gowing (who had joined the Trustees in 1953), were tasked with putting together a document to support the Director’s letter to the Treasury ‘requesting a special grant and explaining the importance of the work and the fact that an opportunity to purchase it at this price, or possibly ever again, might not recur’.74 Moore also strongly supported the acquisition during the meeting, again coming out in favour of sculptural works over paintings: ‘Mr. Moore said that, in his opinion, these sculptures were much finer as works of art than some of Matisse’s pictures’. In February 1956 it was reported to the Board that the Treasury had agreed to an additional purchasing grant of £5,000 to help to buy the four Matisse bronzes: Moore offered ‘to assist in siting the bronzes’.75 An unsigned letter to Moore (probably from Norman Reid, then Deputy Director) in May 1956 asked for the sculptor’s advice in spacing the Backs along the big wall on which they were to be shown.76

Moore in his role as Trustee also acted as an intermediary between the Gallery and artists and collectors. In 1953 the Board decided to purchase some maquettes arising from the Unknown Political Prisoner competition (for which Moore had been advising the organising committee) but declined one by the constructivist sculptor Naum Gabo, as well as another work by him put forward for consideration, Construction in Space 1952. The Trustees did, however, express the desire to purchase a work by Gabo, examples of which they wanted to see in the flesh. ‘Mr. Moore undertook to convey the Board’s views to the artist’, the minutes read.77 A copy of Moore’s subsequent letter to Gabo is held in the Tate’s archive:

Perhaps you know I am one of the Trustees of the Tate Gallery. At the Trustees’ last meeting we talked about trying to make the Tate sculpture collection properly representative, and I was asked to give my list of those I thought should be represented, and of course your name was one of them. A work of your brother, Pevsner, was up for consideration but only by photograph. The Tate has not got a great deal of money to spend, it only gets a relatively small grant and the price of the Pevsner was more than the Tate could afford at the present low state of its funds. I said that it was equally, if not more, important to have your work represented in the Tate ... However, this is only an enquiry as I am but one of the Trustees, and the rest of them are not always unanimous in their appreciation of contemporary work, so it may be that nothing will come of this enquiry, but I hope personally very much that we shall have a work of yours. – To me it is very important that we should.78

Moore’s letter ended with a memory of meeting him on the boat going to America, the fact that he heard news of him via mutual friends like Herbert Read, and a mention of his own family.79 The sculptor’s reference to Pevsner’s work was quietly diplomatic, as the Tate did indeed acquire his Maquette of a Monument Symbolising the Liberation of the Spirit 1952 (Tate N06162) in 1953, as agreed by the Board prior to Moore’s letter to Gabo.

Moore also acted as an intermediary in 1955 when the Tate was offered as a gift a sculpture by the sculptor Germaine Richier: ‘Mr. Moore informed the Board that he had been approached by a person, who wished for the time being to remain anonymous, but who had offered to present to the Gallery “Water” a bronze by Germaine Richier which had been in the recent exhibition of her work at the Hanover Gallery. The Board authorised Mr. Moore to say they would gladly accept this offer’.80 Richier’s Water 1953–4 (Tate T00075) was purchased from the Hanover Gallery with the help of Lord Sainsbury and Robert Sainsbury: the latter, a collector of Moore’s work and friend, was perhaps the unnamed benefactor the sculptor referred to.

In June 1955 the Board minutes record that Rothenstein had been seeking Moore’s advice about the purchase of a bronze by Giacometti, and that he had also been tasked with deciding the merits of two sculptures by Elizabeth Frink.81 Even after his Trusteeship had finished, Moore was still in contact with Rothenstein about potential acquisitions: a letter of 1960 asks Moore’s opinion on the bronze works of the sculptor Fazzini, as the Board were undecided.82 Conversely, Rothenstein wrote to Moore in 1963 to let him know the Board had rejected his suggested purchase of a work by John Warren-Davis.83

The taste and judgment of the artist Trustees during the period that Moore served on the Tate Board could also cause difficulties for the Director, as Rothenstein pointed out in his autobiography, bemoaning their adherence to the ‘modern movement’: ‘They would prefer to acquire, I came to see, an inferior Picasso to a first-rate Pre Raphaelite’.84 When Rothenstein brought sculptures by Manzù and Marini to the Board in 1950 following a visit to Milan, it rejected them, causing the Director to reflect bitterly in his diary about the inadequacy of his powers of persuasion and what he saw as a lack of consistency in the Trustees’ decisions.85 The Board minutes, in fact, record that the Trustees asked for other examples of works by the two sculptors, in particular, Marini’s Horseman 1947 (Tate N06009), which the Tate did subsequently acquire.86 Moore also gave his support to a subsequent Manzù purchase.87 It is likely that Moore was involved in this overriding of the Director’s taste, given his involvement with the dealer Curt Valentin, who had also begun to represent Marini in the U.S.88 When in 1952 the Chair of the Board, Lord Jowitt, raised a concern about Trustees declining works which ‘would be most acceptable to Embassies and the houses of Colonial Governors’, Moore and Coldstream were quick to counter, warning ‘against the acceptance of any principle which might lead to the lowering of Tate’s standards’.89

Sculpture’s technicalities and display

There is evidence from the Board minutes of Moore’s status as an authority not only as an adviser on acquisitions but also as an expert on practical matters relating to sculpture. In July 1952 the minutes reported that a bronze cast of James Havard Thomas’s Cassandra c.1912–21 (Tate N06082) ‘had now been completed with much valuable help and advice from Mr. Henry Moore’.90 The following year, Moore was involved in a more complex question of casting concerning Eric Kennington’s Reclining Figure of Colonel T.E. Lawrence 1939, a monument in the Church of St. Martin, Wareham, Dorset.91 Kennington had offered the Tate a cast of this work, which he would sell them for the price of casting.92 Moore ‘recommended that it should be cast in ciment-fondue [sic] which would cost approximately £100’, but two of the Trustees, Coldstream and John Fremantle, questioned the status of casting an existing monument, raising an issue about sculptural reproduction that has often dogged the medium.93 Moore countered their doubts with practicality, asserting that ciment-fondu ‘was a permanent medium and could be exposed outside’, and tacitly supporting Kennington’s project.94 The Board remained unconvinced: ‘The Chairman reminded the Board that original works of art only were eligible for inclusion in the collection and the Board resolved that the Director should find out whether the cast was to be made from the carving or from a preliminary cast for it, and report to the next meeting’.95 Later that year, however, Board minutes recorded that a cast (Tate N06230) had indeed been ordered from the sculptor, undoubtedly another manifestation of the sway that Moore’s opinions as a practising and successful sculptor held with both the Tate’s director and the Board.96

Moore continued to provide advice after his Trusteeship ceased in his letters to Rothenstein, writing in August 1959: ‘I think it is a good idea of yours to ask the Kunsthaus Zurich to make a cast of their base for the Brancusi. It looks to me as though it could have been designed by Brancusi himself, anyhow it is much better than the base our one is on’.97

An important and more substantial intervention into the Board’s business concerning sculptural matters came in 1954, under the heading ‘Sculpture Hall Wall Covering’:

Mr. Moore explained that he had long been concerned about the way the colour of the stone in the sculpture hall failed to show off the sculpture to the best advantage. The light in the hall was bad enough and was further absorbed by the walls, which were of an extraordinarily unsympathetic colour. He suggested that a special kind of stone paint could be applied which would leave the character and the texture of the stone intact and improve the colour. A light matt surface was required and the hall would benefit by increased lighting in any case. He did not agree with a suggestion by Professor Coldstream that the walls could be painted off-white and covered with modern tapestries as he thought it distracting to mix paintings or tapestries with sculpture in that setting.98

Just prior to this Trustee meeting, Moore had been into the Sculpture Gallery to look at its lighting, according to a letter from the beginning of March from Moore to Norman Reid, the Tate’s Deputy Director, in which the sculptor thanked Reid for ‘arranging for two experimental spot-lights for the Sculpture Hall on March 18th’.99 Clearly the effect created must have displeased him, and the increased lighting may have drawn attention to the colour of the walls that he found so jarring. Moore’s statement here very much tallies with ‘modern’ approaches to the display of sculpture, against plain walls with no distractions. This incident showed him again at odds with the opinion of Hendy, who suggested ‘that the walls could be covered with curtains of a suitable material’. Moore’s advice was apparently heeded, as the Board resolved to approach Lady Duveen and family to see if they ‘would be agreeable to have the walls treated with colour’.

Buying Moore’s work

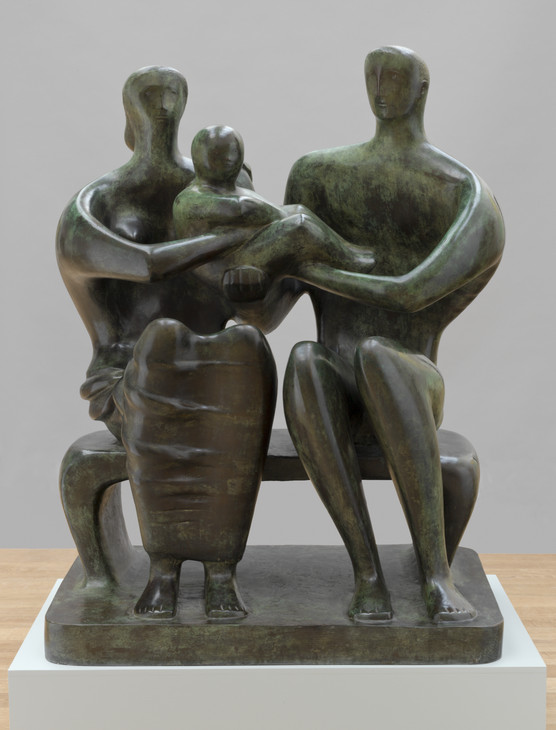

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Bronze

object: 1540 x 1180 x 700 mm, 475 kg

Tate N06004

Purchased 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore OM, CH

Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

I am sure I can persuade him to be satisfied with half the commission he made on the Museum of Modern Art one, that is by me letting him have the second cast for £1850 instead of £2000. Although this means me losing a little, I am only too happy about it, to think that the Tate will be having this group.102

Valentin had first made contact with Moore in 1942 to ask him to show his recent drawings at his Buchholz Gallery in New York, in the process narrowly beating Pierre Matisse to the post in becoming Moore’s U.S. dealer (by the sculptor’s own account).103 The way Moore painted the negotiations over the price of the Tate’s Family Group gave the impression that he was very close to Valentin, wielding a certain amount of power and influence over his dealer. He also highlights his own willingness to lose money in order to benefit the Tate; a strategy of course that would benefit him, by having work in the collection of a high-profile, prestigious art institution.104 Rothenstein replied to Moore’s letter a week later, expressing his gratitude for the suggested price of £2,100, and also himself highlighting the sculptor’s generosity in possibly losing money on the deal: ‘I must confess that I am a bit concerned at the suggestion that this arrangement would involve you actually taking a loss ... if a small further adjustment can be made to preclude the transactions involving you in a loss, I am sure that the Board would wish it’.105 However, this adjustment did not appear to materialise, as the minutes of a further meeting record the purchase of the work at the agreed cost of £2,100.106 A follow-up letter from Moore the following year included an account of the sculpture’s costs, although the artist claimed not to need to explain further the reduction in price ‘by £500’, as it had already been ‘explained in letters at the time’, and reiterated his pleasure at the work’s entry into the collection: ‘I am very happy indeed, of course, that the Tate is having this piece’.107 In 1955 the Family Group came up again in a Board meeting, this time for a less happy reason: a mistake had been made in using £1,000 from the Charles Kerr Fund towards the payment for this work, a fund ‘the use of which was entirely restricted to painting’, an issue that was later to return to haunt Rothenstein108.

Moore’s work continued to be acquired by the Tate during his service as a Trustee. His Girl 1931 (Tate N06708) in Ancaster Stone, for example, was purchased from the Whitechapel Gallery for £500 in 1952.109 His King and Queen 1952–3 was offered on a temporary loan in 1954 by Valentin, ‘on condition that it was exhibited as being lent anonymously’, and a cast subsequently made especially for the Tate in 1957 (Tate T0228).110 That there was some concern felt about the conflict of interest arising in acquiring the sculptor’s work while he was still serving as a Trustee is demonstrated by a letter from Rothenstein to Moore in January 1957 on the Tate’s plans to acquire more work:

You will perhaps remember that while you were still a Trustee I mentioned to you the wish of the Board to amplify the representation of your own work in the Gallery, and that you replied that you of course warmly welcomed the idea but would prefer that consideration of the matter be deferred until you were no longer a member of the Board.111

In 1960 a letter from Rothenstein confirmed the Trustees’ decision to purchase Divided Form 2, and added thanks for a reduction in its cost: ‘They immensely appreciated your generosity in reducing the price from £7,000 to £5,000’.112 Moore’s dealings with the Tate regarding the purchase of his own works were a mix of confident benevolence and a certain discretion about his situation. It is perhaps telling that when in June 1954 a discussion at the Board of Trustees tackled the question of whether purchasing prices should be included in annual reports (as they had been in the pre-war period), Moore was quick to point out the disadvantage of this from the artist’s perspective: ‘Mr. Moore thought that to include prices might be unfair to artists, some of whom may have lowered their price for the Gallery’.113

The Degas affair

Tate’s acquisition of Moore’s Family Group via Valentin and with Moore’s intervention set the scene for the controversy that arose in the wake of the Gallery’s purchase of Degas’s Little Dancer in the 1950s. The Board meeting at which the initial decision was taken, the same at which the purchase of Moore’s Girl from the Whitechapel was agreed, took place in June 1952 in the absence of Moore, as well as of Sutherland and Piper.114 A few months later, however, doubts had been raised about the price agreed for this sculpture. The Director’s Report in the minutes of the meeting of October 1952 included a copy of a letter sent to Valentin, and his reply. First, Valentin was asked about his alleged remarks to Trustees concerning the purchase:

At the last meeting of the Tate Board several Trustees said that they had been informed by two authorities, one of whom was yourself, that in their opinion, the price of £9,000 odd, paid for the Little Dancer, by Degas, was very excessive, and that examples were available in the United States for around £5,000, and possibly even for £4,000. The British Treasury would be unlikely to sanction its purchase for dollars, but I am writing to ask whether by any chance you know of one which might be purchased for £’s or frs. I need not tell you that I should be grateful for your advice.115

Valentin’s reply is worth quoting at length:

I guess it is really none of my business to criticize prices the Tate Gallery pays. On the other hand, as you probably know, the Tate Gallery is one of the museums in the world which interests me most; therefore, I was really amazed to read in the LONDON TIMES about the price the Tate Gallery paid for the little ‘Dancer’. It reminded me that I had sold one cast in 1945 to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Virginia, for 4,300 dollars. The only people to whom I talked about this matter were my friends Graham Sutherland, Henry Moore and John Piper. But I did not say I knew of another cast available either in the United States or in Europe. I might have said that I did not think the bronze should have cost more than 5,000 pounds sterling; perhaps this is my very personal opinion. Also I could not help comparing the price and the piece with the slightly smaller version of the same bronze which I saw at the Lefevre Gallery in London this summer, and which was priced at 900 pounds sterling.116

Valentin names the Trustees to whom he had talked directly: the same three artists who had sent their apologies at the June meeting where the initial decision was announced.

Moore was clearly one of those on the Tate Board in the early 1950s who was prepared to cast doubt on Rothenstein’s judgment in agreeing a purchase price for the Degas sculpture. The background to this was his relationship with Valentin, who had become a close friend, spending every Christmas at Hoglands between about 1946 and 1952. With Valentin’s help, Moore had demonstrated how he could give the Tate a good deal on the acquisition of his own work. To buy a Degas sculpture at what seemed like an excessive price stood undoubtedly in stark contrast to this. The Trustees’ doubts about the price paid for the Degas fanned the fires of tensions developing within the Tate’s administration, largely due to the machinations of its Deputy Keeper, LeRoux Smith. LeRoux was an artist and curator who had trained and worked in England but whom Rothenstein had met in South Africa. LeRoux had been the Director of the Pretoria Art Centre and one of the artists included in a touring show at the Tate in 1948, Contemporary South African Painting, Sculpture and Drawing. Rothenstein’s attention had been drawn by Moore to the work of another South African artist, Enslin Hercules du Plessis, in a letter of 1943.117 LeRoux and Du Plessis both exhibited with the New Group in South Africa in the late 1930s.

Moore was clearly one of those on the Tate Board in the early 1950s who was prepared to cast doubt on Rothenstein’s judgment in agreeing a purchase price for the Degas sculpture. The background to this was his relationship with Valentin, who had become a close friend, spending every Christmas at Hoglands between about 1946 and 1952. With Valentin’s help, Moore had demonstrated how he could give the Tate a good deal on the acquisition of his own work. To buy a Degas sculpture at what seemed like an excessive price stood undoubtedly in stark contrast to this. The Trustees’ doubts about the price paid for the Degas fanned the fires of tensions developing within the Tate’s administration, largely due to the machinations of its Deputy Keeper, LeRoux Smith. LeRoux was an artist and curator who had trained and worked in England but whom Rothenstein had met in South Africa. LeRoux had been the Director of the Pretoria Art Centre and one of the artists included in a touring show at the Tate in 1948, Contemporary South African Painting, Sculpture and Drawing. Rothenstein’s attention had been drawn by Moore to the work of another South African artist, Enslin Hercules du Plessis, in a letter of 1943.117 LeRoux and Du Plessis both exhibited with the New Group in South Africa in the late 1930s.

Graham Sutherland took a high profile role between 1952 and 1954 while LeRoux’s campaign against Rothenstein was at its height, writing to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rab Butler, and finally resigning from the Board of Trustees at the end of January 1954. Moore’s role during this period, however, is less clear. When Sutherland’s resignation was raised in Parliament, in the context of more general concern about the Tate’s misuse of bequest funds, one defence of the Trustees’ actions was that ‘the irregularities ... took place over a number of years and in circumstances for which a good many of the present trustees were not responsible’.118 Moore, however, was the longest-standing artist Trustee at this point, having served for about twelve years in total. Moreover, the purchase of his own work, albeit presumably without his knowledge, had been subject to one of the administrative ‘irregularities’ alluded to (the purchase of sculpture using a fund restricted to painting). Moore was a signatory to the Report by the Trustees of the Tate Gallery published in February 1954, which provided accounts of the infringements of terms of funds (including references to purchases of works by Giacometti, Degas, Renoir, Matisse and Picasso, but not Moore), as well as a rebuttal of potential criticisms of excessive prices paid: ‘It can always be claimed that a picture which at any previous date could have been bought more cheaply is at the time of its purchase an extravagance. The logical implication of this would be that purchases should be confined to the works of unknown artists, but this is scarcely the function of a National Collection’.119 With his connections to European modernism, Moore had also arguably been the most authoritative artist voice on the Board of Trustees with regard to the acquisition of works by the artists in question (more so than Coldstream or Edward Bawden, the other artist Trustee on the Board at the point, Sutherland just having resigned).

Rothenstein’s own account of the ‘Tate Affair’ in his 1966 autobiography made several allusions to the disappointment he felt at the Trustees’ behaviour during this period. In particular, he reflected on the younger artist Trustees as a new kind of constituency, having been largely prior to the 1940s Royal Academicians: ‘Aware though I was of the contribution that they might make, I was still very blind to the politics of power or prestige in which some ambitions find a congenial fulfilment’.120 Rothenstein was also quick, however, to distance Moore specifically from this: ‘It need hardly be said, however, that both as artist and as man Henry Moore, despite a sense of commitment to fellow-artists that in these days led him into courses that he afterwards regretted, was of a calibre that transcended such preoccupations’.121 Reading between the lines here, Moore clearly did turn against the Tate’s Director, and moreover Rothenstein retrospectively viewed the artist Trustees as forming a ‘self-assertive, highly articulate, group with a sense of solidarity as artists’.122 When the Trusteeship of Kenneth Clark was turned down by the Treasury in 1952 against Rothenstein and the Board’s wishes, the Director was told ‘that the responsible authorities took the view that the group of artists in question was powerful enough as it was’.123

Rothenstein’s account of the controversy, which extended to attacks in the press orchestrated by Leroux (who was close to the press baron Lord Beaverbrook) and by the art historian Douglas Cooper, a friend of Sutherland, calling for the Director’s resignation from the Tate, later expressed his feelings of deep betrayal that none of the Trustees whom he liked and admired publicly defended him or asked for his side of the story.124

Moreover, on one level, Rothenstein’s later account of the affair hints that Moore himself was to some extent culpable in the administrative errors in Trust Funds that fuelled the public controversy. When the Director was told that his Board could not give him a vote of confidence, his ‘Treasury superiors snorted with incredulity; “as if”, they said, “the Trustees were not every bit as responsible as you”’.125 Rothenstein went on in his autobiography to wonder at how every member of the Board missed the mistake in using the Kerr Fund as part payment towards a bronze by Moore, given that during a period of eight months while the bronze was being cast the make-up of its payments was regularly recorded in Board minutes.126 But the relationship between Moore and Rothenstein recovered, the sculptor being remembered by the director as one of the few Trustees of the period to express regret for their actions.127 Moore later told Berthoud that he had finally supported Rothenstein as opposed to LeRoux or Cooper, whom he evidently disliked.128 One of the minutes for a Board meeting at the National Gallery records a discussion about a proposed tour of a Delacroix exhibition organised by Douglas Cooper, and Moore’s stern advice not ‘to collaborate in any way with Mr Cooper’.129

In 1958, according to Rothenstein’s account, Moore told the latter’s wife Elizabeth, ‘When I think what we almost did to John! I can never remember it without horror’.130 By the early 1960s a letter from Moore to Rothenstein indicates a close rapport, Moore expressing his delight that Rothenstein is dedicating his Phaidon book British Art since 1900 to him, and signing off ‘with love to you both from both of us. Yours ever’.131 When Moore was to raise the idea of a major gift of his work to the Tate a few years later, Rothenstein wrote to him enthusiastically, mentioning too the reflected glory it would entail for himself. ‘I should feel this to make a wonderful conclusion to my Directorship’.132 In his own very defensive account of the 1950s, Rothenstein implied Moore’s involvement while also exonerating him, perhaps with an eye on later developments, including Moore’s gift to the Tate, as his autobiography was published in 1966. All along, as we have seen, Moore was crucial to Rothenstein’s strategies as Director, seen as an ally and good judge of modern art, but perhaps most importantly himself a significant modern artist whose presence on the Board of Trustees enabled the Tate to build substantial holdings of his work.

Moore’s role as a Tate Trustee during the tumultuous period of 1952–4 is complex and ambiguous. From today’s perspective, Moore’s role in raising questions about the price paid for Degas’s Little Dancer is also complicated by its source, the dealer Valentin, who died in the summer of 1954 while staying at Marini’s villa in Forte dei Marmi, and was later always seen as highly respected in the art world, ‘as lovable as a human being as he was inspired as a dealer’, in Berthoud’s account.133 Recent research has suggested that when dealing in art classed as ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis, Valentin was sending the profits made back to the Third Reich; indeed, this deal allowed him to acquire ‘unwanted’ works in Germany and sell them abroad at below their market value, giving him the appearance of a dealer-benefactor for major art institutions in America and Europe. Valentin’s reported comments, then, on the price of a Degas sculpture, which contributed to the Tate’s difficulties during the 1950s, can be seen in the light of his dealings, where his apparent bravura about his ability to find cheaper versions of modern art works has to be tempered by the knowledge that he was potentially passing off looted works as ‘bargains’.134 There is no evidence that Moore knew about this aspect of Valentin’s dealing.

From the Tate to the National Gallery

During Moore’s second period as a Trustee at the Tate, the sometimes vexed relationship between the Tate and the National often arose, and the sculptor contributed comments to discussions, particularly concerning the division of art works between the two institutions, in the context of the Courtauld Bequest, the Massey Report, and the National Art Collections Bill. Moore’s role in this respect appears to have been diplomatic and conciliatory, as some of his contributions to the debate implied: ‘Mr. Henry Moore considered that the Trustees would have to face the problem squarely sometime; the transfer of pictures could not be postponed indefinitely, however awkward and regrettable it might prove’; ‘Mr. Moore emphasized the need for some kind of guidance in order to avoid tension between the two institutions’.135 In May 1955 Moore was nominated as the Tate’s representative on the Board of the National Gallery, an arrangement that had been set in place precisely to help negotiate the relationship between the two galleries.136 In October that year the minutes of the National Gallery Board meeting record his balanced intervention into a discussion about the transfer of thirty-one nineteenth-century paintings from the Tate: ‘Mr. Moore ... thought that some of the Trustees of the Tate Gallery had strong feelings in the matter and he did not think there was any hope of their agreeing to part with, for example, “La Baignade” by Seurat for a considerable time to come. On the other hand, he thought that discussions of the matter with the Tate Gallery might profitably begin soon’.137 When Moore’s term of office at the Tate came to an end in 1956, Coldstream replaced him as the Tate representative, but a few months later Moore was welcomed back onto the National Gallery Board as one of its own Trustees.138

On the Board of the National Gallery, Moore could be freer to support causes as he saw fit. Beyond official tasks that he was given, like representing the Gallery in a meeting with the Chancellor of Exchequer to discuss an increase in its Grant-in-Aid in early 1957 (with no success),139 or analysing the Gallery’s previous attendance figures,140 Moore was largely involved in passing judgment on proposed acquisitions, and occasionally in intervening in debates involving sculpture. Proposed purchases in which he became involved included those of Giorgione’s Tramonto in 1957, Renoir’s two panels titled Dancing Girl in 1961 and a painting by Piazzetta, The Music Lesson, in 1973.141 Moore was an important advocate of Cézanne’s Grandes Baigneuses in 1964, claiming in the Board meeting that ‘in this and the other versions of the picture Cezanne was expressing his ambition of competing with the Old Masters’142, while also attending its press view as a supportive presence.143 In 1959 Moore acted as an intermediary in the Gallery’s purchase of Degas’s After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, offering to write to its owner, Harry Walston, whom he knew, to ask for a reduction in its price.144

Moore’s main intervention in sculptural matters on the National Gallery Board dealt with a proposal in the late 1950s to re-situate the statue of James II by Grinling Gibbons in the Gallery’s front garden to make way for a statue of Raleigh based on a model by Fiore de Henriquez (1901–2004). Moore came out in strong support for Grinling Gibbons’ sculpture: ‘Mr. Moore deplored the suggested removal of the statue of James II which was one of the finest in London and could be seen in its present position by the maximum number of people. He thought the statue of George Washington, on the contrary, was very poor and should be the one removed if either were to be taken away’.145 It is tempting to see evidence here of Moore’s support for English art and culture, in opposition to the proposal to put together two figures with American interest, the existing Washington statue made after a model by Houdon. The Royal Fine Art Commission, on which Moore also sat, was also mobilised in opposition to the scheme, as he reported to the National Gallery Board the following year.146

If during his Tate Trusteeship Moore had not always supported his Director, the same ambivalence was true, albeit to a lesser extent, of his Trusteeship of the National Gallery. Despite Berthoud’s claim that Moore ‘was perhaps rather too inclined to support Philip Hendy’,147 the evidence of Board meetings from both the Tate and the National Gallery show a more nuanced picture. At the Tate Moore had on several occasions disagreed with Hendy on acquisitions, and in one case on the viability of an exhibition of Mexican art, in which Moore himself would naturally be expected to take an interest: ‘In reply to Sir Philip Hendy’s objection to the exhibition on the grounds that it fell almost entirely outside the scope of the Tate, Mr. Moore stated that the nature of early Mexican art made the subject peculiarly relevant to contemporary art’.148 On a more significant question at the National Gallery concerning the Hugh Lane bequest and whether a number of paintings from the Gallery should be given to Dublin, Moore initially supported Hendy, but then changed his mind. In October 1957 Moore stated in a Board meeting that ‘It was the Trustees’ duty to keep the pictures at the Gallery and any other course would be an admission that they were in the wrong’.149 A decade later, however, when considering the loan of works from the Hugh Lane bequest to Ulster Museum and delaying their return to London, a situation Hendy was not happy with, Moore took a different view: ‘Mr. Moore, who explained that he had opposed the original settlement, said that he now favoured a loan to Belfast and was convinced that Ireland should be treated as one country’.150

Moore’s last meeting on the Board of Trustees of the National Gallery was on the 4 April 1974. On the 5 April, a letter from new Director Michael Levey expressed gratitude on behalf of the Gallery’s staff: ‘We are deeply conscious of all your friendly interest over the years, as well as naturally valuing your experienced sensitivity in front of paintings of all kinds. Your reaction has always been of the deepest interest and was bound to be received with fond respect’.151 This letter reflected one of Moore’s key functions as a Trustee: to provide judicious responses to art works. But this analysis of his roles at both the Tate and the National Gallery also reveal another side of Moore’s identity as a strategic operator, negotiating some of the twists and turns of gallery and art world politics, and often providing a balanced view, sometimes opportunely shifting positions and allegiances over several years. When Moore was asked in 1972 by Edward Playfair, Chair of the National Gallery Trustees, to think about a successor to his post, the terminology used was revealing: ‘By the time you go I feel that the Board would gain by having an artist who is well accustomed to our ways’.152 Moore was indeed well attuned to art committees and Board meetings by the 1970s, able to support and challenge while also, crucially, retaining a sense of his own artistic identity. Rather than being at the ‘heart’ of the establishment, he knew instead how to work with it: how to respond to and engage with its ‘ways’.

Shaping his own legacies

The role Moore had taken as a Trustee both of the Tate and the National Gallery, particularly with respect to judgements passed on not only modern works of art but also latterly historical works from a long artistic tradition, no doubt heightened his sense of his own place in art history, a sense that had long been nurtured by supporters like Clark and Read. This may have had some bearing in Moore’s shift away from the Tate Gallery in the later 1960s as the complexities of his proposed gift were being worked out, and in the shadow of the notorious letter to the Times signed by artists of a younger generation, dismayed at what they perceived to be Moore’s increasing dominance at the gallery, and accusing the Tate Gallery and implicitly Moore himself of trying ‘to predetermine greatness for an individual in a publicly financed form of permanent enshrinement’.153 The snub that Moore experienced at this moment, often seen as one of the spurs for his donation to the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) of works that were intended for the Tate Gallery, can only have distanced him further from the artists of his time. As a Trustee of the Tate, he had played an important role in supporting fellow artists; at the National Gallery he was inevitably at a remove from such concerns, engaging to a greater degree with issues of artistic legacy and posterity, concurrently as he was contemplating these in relation to his own oeuvre. Why indeed would an artist at the stage of his career that Moore had reached not seek a ‘form of permanent enshrinement’?

The permanent display of his plasters in Toronto in the specially-designed Henry Moore Sculpture Center, with its echoes of the glyptotheque and the Italian interest in plaster casts seen as works in their own right, such as those by his friend Marini, could not help but have certain classicising overtones. Moore had been well received for his major exhibition in Florence in 1972, and had been spending more time in Forte dei Marmi, near Carrara, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, having bought a holiday home there. Opening in 1974, the same year that Moore’s Trusteeship at the National Gallery came to an end, the symbolism of the Art Gallery of Ontario’s museum enshrinement of his work was striking, and strikingly eclipsed the Tate’s own eventual presentation of his gift in 1978, despite apparently having the Tate’s discreet blessing.154 Moore’s own account of the Toronto gallery, included in Peter Seldis’s 1973 book on Moore in America, charted his own realisation of the artistic value of his plasters, prompted by ‘a friend who works at the Victoria and Albert Museum’, that is to say someone used to dealing with works from much earlier periods.155 Moore mentioned the fact that the Tate’s proposed extension would ‘not be built for some years’, but that he had also not envisaged homing all of his preliminary plasters in that institution: ‘...nor would I want to give them all the plasters’.156

Exactly why Moore should not want to give a more substantial gift of the plasters to the Tate Gallery, which was a major blow to the London gallery, is unclear. One possibility is that Moore felt he could have greater degree of control over the installation of his work at the Art Gallery of Ontario, as a special purpose-built gallery was to be constructed. His 1973 account refers to a visit to London with the AGO’s director, the collector Sam Zacks (who helped to finance the project), and the architect of the Henry Moore Sculpture Center, in order to look at ‘different museums so that I could show them what was right or wrong with them as far as the display of sculpture is concerned’.157 When he saw a model of the proposed gallery, he was pleased with its structure in that respect: ‘I could see that my ideas about that very important subject had been followed’.158 We have seen how Moore at times took a strong view about aspects of the display of sculpture at the Tate Gallery, and as he acquired greater experience of assessing museum displays as a Trustee, both of his own work and that of others, the chance to play a central role in the creation of a new space for his sculptures may have been too good to miss.

It is possible, too, that Moore while was looking beyond the modern British art world in establishing a personal display space in Canada, he was also looking to a broader, longer artistic tradition. Zacks, a driving force in bringing the Moore works to Toronto, collected early twentieth-century masters as well as antiquities. Another important figure in the development of the Henry Moore Sculpture Center, Allan Ross, wrote in wooing letters to Moore in 1967 of ‘a splendid classical structure to adequately house the collection you have in mind for Tate Gallery and which they for some years apparently cannot accommodate’, as well as insisting ‘I do so much want you to continue to grow world-wide’.159 In 1973 Moore began to be represented by a branch of Daniel Wildenstein’s art dealing business in London, as the only contemporary British artist to be associated with the gallery, which dealt mainly in impressionists and old masters. In a striking parallel, Daniel’s father Georges Wildenstein had taken on Picasso in the 1920s, at the time the only living artist on their books, putting the latter into a stable alongside the likes of Chardin in an established European tradition. In both cases the latent message was clear: this is an artist who belongs to a tradition, whose reputation is already affirmed and secure in the pantheon of greats, and whose value as a solid financial investment is also assured.