Henry Moore OM, CH Bird 1959, cast 1960

Image 1 of 8

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Bird

1959, cast 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Animals, and in particular birds, presented subjects that Moore returned to throughout his career. While this bronze sculpture from 1959 may not represent a particular species of bird, it demonstrates how Moore sought to make a work that conveyed the ‘vitality’ or inner life force of living creatures.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Bird

1959, cast 1960

Bronze on a Hoptonwood limestone base

121 x 375 x 130 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from an edition of 12

T02282

Bird

1959, cast 1960

Bronze on a Hoptonwood limestone base

121 x 375 x 130 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from an edition of 12

T02282

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone, April–May 1966; City Art Gallery, Plymouth, June–July 1966, no.38.

1967

Henry Moore, Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield, July–September 1967, no.37.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, no.105.

1975

Henry Moore: Fem Decennier, Skulptur, Teckning, Grafik 1923–1975, British Council touring exhibition: Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, June–July 1975; Kulturhuset, Stockholm, 12 August–5 October 1975; Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum, Aalborg, October–November 1975, no.57.

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976, no.61.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.81.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1982–3

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, November 1982–January 1983, no.56.

1983

Henry Moore: Esculturas, Dibujos, Grabados – Obras de 1921 a 1982, Museum of Contemporary Art, Caracas, March 1983, no.123.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.44.

2010

Object, Gesture, Grid: St Ives and the International Avant-garde, Tate St Ives, St Ives, May–September 2010.

References

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Gallery, London 1960 (another cast reproduced no.65).

1961

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Galleria Nazionale de Arte Moderna, Rome 1961 (another cast reproduced no.49).

1961

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Musée Rodin, Paris 1961 (another cast reproduced pl.35).

1962

Henry Moore: Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1962 (another cast reproduced pl.17).

1963

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Art Centre, La Jolla 1963 (another cast reproduced no.59).

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, London 1965, no.445 (?another cast reproduced pls.78a–b).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.405 (?another cast reproduced).

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo 1968 (another cast reproduced no.99).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–69, London 1970 (?another cast reproduced no.575).

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence 1972, reproduced no.105.

1973

Henry J. Seldis, Henry Moore in America, New York 1973 (another cast reproduced p.182).

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Cartwright Hall, Bradford 1978, reproduced no.81.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.41.

1981

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2282 Bird’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.126.

1982

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, exhibition catalogue, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City 1982 (another cast reproduced no.310).

1983

W.J. Strachan, Henry Moore: Animals, London 1983 (?another cast reproduced no.23).

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.74.

Technique and condition

Bird 1959 is a small bronze sculpture representing a bird, and is attached to a rectangular base made from polished Hoptonwood limestone.

The shape of the bird’s large beak suggests that it may have been formed from found objects, perhaps parts of an existing mould to which Moore added plaster to create the finished model. The marks on the surface of the bronze are indicative of the type of tool marks found on Moore’s other sculptures, and were made on the original plaster model from which the bronze sculpture was cast. There are surform marks on the right side of the bird and marks made using a fine-toothed saw blade in the cavity at the top of the wings. Texture is given to the wings and tail by a series of inscribed cross-hatched lines (fig.1). Bird was probably cast using the lost wax technique. Fragments can be heard moving inside the sculpture, which suggests that it is hollow, although it is not possible to confirm this visually.

Detail of hatched lines on wing of Bird 1959, cast 1960

Tate T02282

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of hatched lines on wing of Bird 1959, cast 1960

Tate T02282

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of patina on tail of Bird 1959, cast 1960

Tate T02282

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of patina on tail of Bird 1959, cast 1960

Tate T02282

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The bronze has been artificially patinated to achieve a variegated green and brown colour (fig.2). First, a layer of transparent brown patina was applied, probably using a solution of potassium polysulphide (also known as ‘liver of sulphur’), followed by a more opaque pale green patina on top. There are many different patina recipes used to produce green colours on bronzes but they often contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts dissolved in water. The solution is usually applied in successive layers until the desired colour is achieved. The green patina has been lightly abraded on the sculpture’s high points to reveal the underlying brown colour. Lastly, a clear wax was applied to protect the coloured surface.

There are no visible inscriptions or foundry marks on the sculpture but it is known that Bird was cast in an edition of twelve plus one artist’s copy at the Art Bronze Foundry in London. The sculpture is fixed from underneath through two recessed holes in the base.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Bird 1959, cast 1960 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, April 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Henry Moore’s Bird 1959 does not depict a particular species of bird but displays certain features that make it recognisable as such. These include a long bill with a smooth and relatively flat upper surface, a short rounded body, and a long feathered tail. The bill and the tail project beyond the front and rear edges of the rectangular Hoptonwood limestone base on which the sculpture sits. From the side the bird’s body can be seen to extend on a diagonal axis, with the bill tilting upwards, the body curving downwards, and the tail projecting horizontally backwards. Consequently the sculpture appears carefully weighted, with the bill and tail counterbalancing each other.

Detail of bill of Bird 1959, cast 1960

Tate T02282

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of bill of Bird 1959, cast 1960

Tate T02282

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of wing and tail of Bird 1959, cast 1960

Tate T02282

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of wing and tail of Bird 1959, cast 1960

Tate T02282

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The bill comprises a wide upper mandible with a flat upper surface and a thinner lower mandible containing a large hole at its far end. This hole appears to delineate the shape of a pelican’s dip netting bill – a large fold of skin connected to a pelican’s lower mandible that acts rather like a net (fig.1). On the right side of the bird the jawline curves smoothly into the wing, underneath which deep recesses evoke the shapes of a skeletal structure. The peaked curve connecting the upper mandible and the wing complicates any sense of anatomical legibility in that the body appears to occupy the position of a head. Similarly, from certain angles the crests of the wings may also be understood to represent eyes. Both wings extend backwards and form a long tail with scalloped edges suggestive of feathers (fig.2). Moore paid particular attention to the surfaces of the wings and tail, marking them with a series of cross-hatched lines to evoke a feathery texture.

From plaster to bronze

Henry Moore

Bird 1959

Plaster

135 x 380 x 130 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Bird 1959

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

When the plaster version was complete it was sent to the Art Bronze Foundry in London to be cast in bronze. At the foundry a mould was made of the plaster sculpture into which molten bronze was poured. Bird was cast in an edition of twelve plus one artist’s copy. Records at the Henry Moore Foundation indicate that the work belonging to Tate is the artist’s copy and was cast in April 1960.2

After it had been cast at the foundry the bronze sculpture was returned to Moore so that he could inspect the casting and make decisions about its patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the bronze surface. Bird has a fairly consistent light brown base patina, over which a light green patina was applied and polished back to reveal the underlying brown colour on the sculpture’s high points.

Origins and development

In 1968 Moore explained the origins of Bird to the photographer John Hedgecoe:

ten years ago I made a teracotta bird table. A big, black crow (I particularly like crows) used to come and eat from this table. I think it came because it was old and sick and it was the only way it could get its food. It had something wrong with its beak and it stood almost horizontally. That bird is why I did this sculpture.3

Henry Moore

Bird 1927

Bronze

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Bird 1927

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Haida rattle from British Columbia, Canada, unknown date

Wood

335 x 110 x140 mm

British Museum, London

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.5

Haida rattle from British Columbia, Canada, unknown date

British Museum, London

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The Henry Moore Gift

Henry Moore presented Bird to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift. The Gift comprised thirty-six sculptures in bronze, marble and plaster and was exhibited in its entirety alongside Tate’s existing collection of Moore’s work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday, which opened in June 1978. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.11 Bird was included in the birthday exhibition and was displayed in gallery nineteen. The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.12 At the close of the exhibition in late August 1978 the Director of Tate Norman Reid reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.13

Bird was cast in an edition of twelve plus one artist’s copy. Other casts of the sculpture can be found in the Gwendolyn Weiner Collection, on permanent loan to the Palm Spring Desert Museum, and the Norton Simon Foundation, Pasadena. The remainder are believed to be held in private collections. The full-size plaster is held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation.

Alice Correia

April 2013

Notes

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.192.

Related essays

- 'I tried to push him down the stairs': John Berger and Henry Moore in Parallel Tom Overton

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- ‘A sincere academic modern’: Clement Greenberg on Henry Moore Courtney J. Martin

Related catalogue entries

Related material

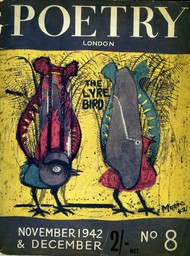

-

Magazine cover

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Bird 1959, cast 1960 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, April 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www