Henry Moore OM, CH Head of Serpent 1927

Image 1 of 10

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Head of Serpent 1927© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

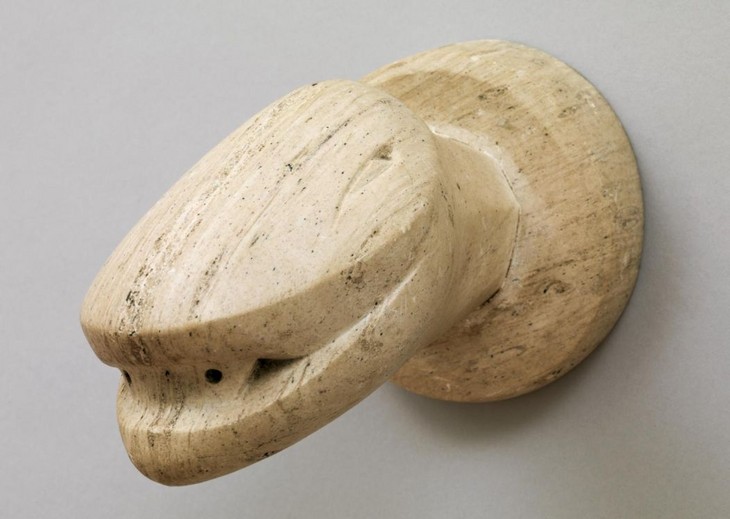

Head of Serpent

1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Head of Serpent is an early example of Henry Moore’s lifelong engagement with animal subjects. Moore himself never commented on this particular work but its subject may reflect his fascination with the art of ancient Mexico in which the snake was an important emblem.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Head of Serpent

1927

Travertine marble

180 x 114 x 114 mm

Lent from a private collection 1994

L01766

Head of Serpent

1927

Travertine marble

180 x 114 x 114 mm

Lent from a private collection 1994

L01766

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist by the artist’s sister, Mrs Mary Spencer Garrould, Norfolk, possibly c.1928 and by 1944; thence by descent.

Exhibition history

1928

Henry Moore: Sculpture, Drawings, Warren Gallery, London, 1928, no.2 (as ‘Snake’s Head’).

1961

Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carvings, Marlborough Fine Art, London, June–July 1961, no.10.

1968

Henry Moore, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, May–July 1968; Museum Boymans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, September–November 1968, no.7.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983.

1998

Henry Moore: Friendship and Influence, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, October–December 1998, no.76.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, May–September 2004, no.4.

References

1928

Anon., ‘Yorkshire Miner’s Artist-Son’, Yorkshire Evening Post, 30 January 1928 (Henry Moore Foundation Archive).

1944

Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944, reproduced p.4, pl.4a.

1983

W.J. Strachan, Henry Moore: Animals, London 1983, p.25, reproduced figs.3 and 4.

1988

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, 1957, revised edn, London 1988, no.45, p.4, reproduced p.30.

2000

Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art and the Post-Columbian World, New York 2000, p.104.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, reproduced p.42.

Technique and condition

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Head of Serpent 1927

Stone

object: 180 x 114 x 114 mm

Lent from a private collection 1994

On long-term loan to Tate L01766

On long-term loan to Tate L01766

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore OM, CH

Head of Serpent 1927

Lent from a private collection 1994

On long-term loan to Tate L01766

On long-term loan to Tate L01766

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Head of Serpent 1927 (front view) 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Head of Serpent 1927 (front view) 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

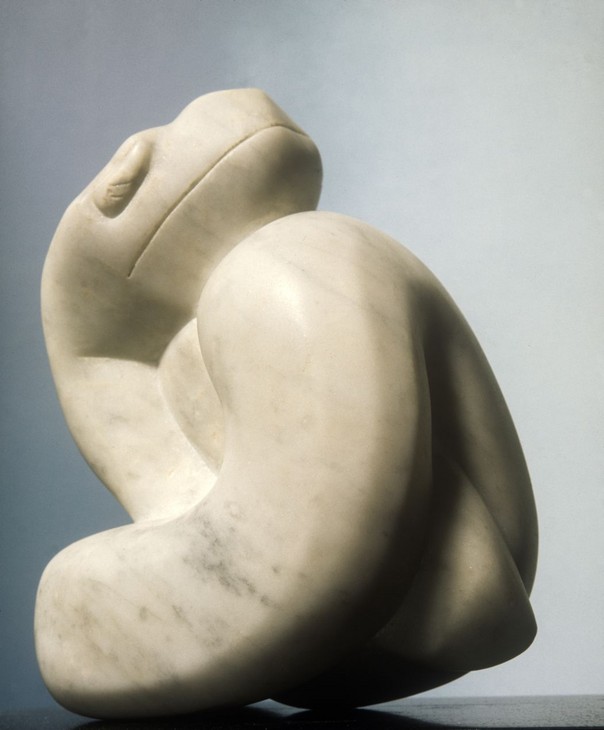

This small, carved sculpture of the head and neck of a serpent is made in buff coloured limestone with intermittent sparkling bedding planes that run from front to back. Such banding is characteristic of travertine marble.

The sculpture is intended for wall mounting and is attached with fixing cement and a single screw to a circular mount which has a bevelled sloping surface to tilt the snake’s head down towards the viewer (fig.1). Moore has carved the snake with smooth planar surfaces that are finished to a matte texture. Narrow shapes are recessed into the surface of the head to represent the creature’s eyes, while inside the mouth are two triangular notches and two neatly drilled holes (the exact purpose or meaning of these is unclear) (fig.2).

Carving a stone object begins with the artist roughing out the shape and removing larger unwanted areas of stone using a hammer and chisels. Point chisels are often used first because the sharp point directs maximum force from the hammer to drive off chunks of stone or, alternatively, a pitching tool may be used. This is a large chisel with a very broad edge that can be used to split stone along its bedding planes.

The sculpture’s shape might then be refined using a claw chisel, which leaves characteristic parallel lines in the surface from its multiple small chisel heads and removes material quickly. The sculptor will further perfect the form using various sizes of chisels at a shallow angle to the surface before using more abrasive tools such as rasps and rifflers. In the case of this sculpture Moore has further worked the stone with files and fine abrasives to achieve a final smooth surface, leaving no traces of the original tool marks.

At this stage of his career Moore favoured what he called ‘direct carving’ where the sculptor works directly on the stone without reference to a model or maquette.

There are no inscriptions on this sculpture.

Lyndsey Morgan

July 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', July 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Head of Serpent 1927 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Head of Serpent is a small, wall-mounted stone sculpture of a snake-like head thrusting forward from a circular base. Sharply incised narrow ovals on either side of the smoothly rounded head indicate the serpent’s eyes. Its jaws are improbably thick, and seen from the side the snake seems to smile. Inside its mouth are two triangular notches and, mysteriously, two neatly drilled holes. The cream travertine marble used in this work has a slight graining, producing black-brown streaks that run along the serpent’s head, emphasising its length and narrow eyes.

The sculpture was made in 1927 when Moore was working as a tutor at the Royal College of Art in London. Moore had taken up a teaching post in the sculpture department in 1924 after gaining his diploma from the college and continued working there until 1931. Although nothing is known about the precise circumstances in which Head of Serpent was made, it was probably carved at Moore’s studio, 3 Grove Studio, Adie Road, Hammersmith, where Moore lived and worked between 1926 and 1929. The sculpture is numbered 45 in the artist’s catalogue raisonné of 1957, which notes that it was made in the autumn of 1927. If correct, this means that the sculpture was completed only a few months before it was exhibited in Moore’s first solo exhibition in January 1928 at the Warren Gallery, London. This exhibition contained sculptures and drawings made over a seven-year period, the earliest work dating from 1922. When it was exhibited at the Warren Gallery, Head of Serpent was listed in the exhibition pamphlet as Snake’s Head. It was re-titled Head of Serpent in 1944 when it was included in critic Herbert Read’s book Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, which was later revised and reissued as the artist’s catalogue raisonné. Subsequent published literature has repeated the title Head of Serpent, but on entering the Tate collection its title was initially revised to Head of a Serpent in order to make the title read more easily. In 2014 the title was changed back to that listed in the artist’s 1957 catalogue raisonné.

The material of Head of Serpent was identified in 1928 simply as stone, and most subsequent publications repeated this unspecific information. In 1983, however, sculpture historian W.J. Strachan identified the stone as travertine marble, which has since been confirmed by Tate conservator Lyndsey Morgan (see Technique and condition).1 The serpent’s head and base has been carved from a single block of travertine marble, a sedimentary rock that is known for its fibrous veining. The marble is found globally, but is commonly associated with quarries in Italy; travertine marble derives its name from the Italian town of Tivoli, and was used in the construction of prestigious buildings in ancient Rome, including the Colosseum. In 1981 Moore explained why he liked working with this particular stone: ‘Travertine has a good quality – ruddy, powerful, strong. You feel you haven’t got to handle it with kid gloves’.2 The ancient Romans used travertine marble as a material for sculpture, a tradition that was continued by Michelangelo in the sixteenth century, and then by Moore, most notably in his commissioned Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–8.

Henry Moore

Snake 1924

Marble

171 x 165 x 127 mm

Collection of Mary Moore

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Snake 1924

Collection of Mary Moore

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

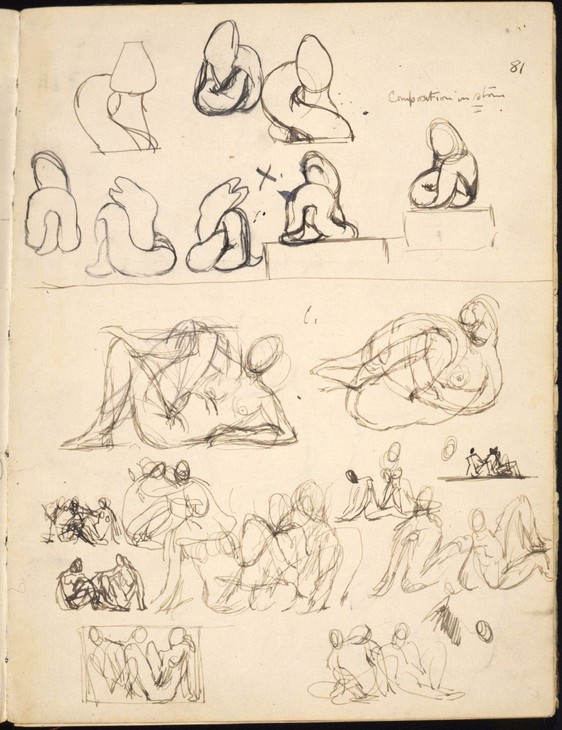

Studies for Snake Sculpture 1921–2 (detail from Notebook No.2), Ink and chalk on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Studies for Snake Sculpture 1921–2 (detail from Notebook No.2), Ink and chalk on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Over the course of his career Moore created four snake sculptures, of which Head of Serpent was the second. The first, Snake 1924 (fig.1), in white marble, presents a snake with the length of its body tightly coiled around itself. This sculpture is directly linked to a series of preparatory drawings which also show a snake coiled around itself, seen from different angles (fig.2). The way in which the upward looking snake’s head rests on its own body in the sculpture replicates the designs seen in Moore’s sketches. Although none of Moore’s sketches from the 1920s correspond as explicitly to Head of Serpent, his sketchbooks reveal that he was interested in animal forms. In his book Henry Moore: Animals, published in 1983, W.J. Strachan suggested that Head of Serpent was a continuation of the 1924 Snake. However, although Snake and Head of Serpent have a shared subject matter, in the later work Moore chose only to prioritise and develop the primary features of the earlier sculpture, namely the head and the mouth, dispensing with the rest of the snake’s body. Moreover, while Snake was designed to be placed on a flat surface, Head of Serpent was fashioned to hang on a wall.

It is likely that the sculpture was originally displayed at or above eye level because the angle of the head tilts downwards, as seen in a photograph showing the sculpture installed at Moore’s 1961 exhibition at Marlborough Fine Art, London. This wall-mounted schema is rare in Moore’s work, although another example in Tate’s collection is Animal Head 1956 (Tate T02277). The third and fourth snake sculptures made by Moore were made decades later and cast in bronze, Snake Head 1961 and Serpent 1973.3

Notebook No.2 is the earliest of six surviving notebooks and many of the drawings contained within it relate to Moore’s coursework for the Royal College of Art.4 Some of the drawings were annotated by Moore, or were subsequently labelled during Moore’s lifetime, as having been made after visits to the British Museum. Moore made regular trips to the museum following his arrival in London in 1921, and used its collection as a source of inspiration for subjects and sculptural ideas that were later developed in the studio. While it is unlikely that the sketches of snakes found in Notebook No.2 were exact copies of specific works in the British Museum, Moore was certainly aware of the various sculptures of snakes in the collection, particularly examples from ancient Mexico, suggesting that his sketches may well have evolved from his observation of these ancient artworks.5

Moore’s knowledge of the arts of ancient Latin and South America was informed by his reading of the art critic Roger Fry’s Vision and Design (1920) as a student at Leeds School of Art in 1920. Fry had included a chapter on ancient American arts in his book, and Moore later recalled that ‘Fry opened the way to other books and to the realisation of the British Museum. That was the beginning really’.6 In 1947 Moore recalled, ‘One room after another in the British Museum took my enthusiasm. The Royal College of Art meant nothing in comparison ... And after the first excitement it was the art of ancient Mexico that spoke to me most’.7 The British Museum had a particularly large collection of ancient Mexican sculpture having acquired its first piece in the 1820s and Moore may have visited the museum’s 1923 exhibition of Mayan sculpture from the Maudlay Collection.

Mexica (Aztec)

Coiled rattlesnake c.1300–1521

Granite

360 x 530 mm

British Museum

© Trustees of The British Museum

Fig.3

Mexica (Aztec)

Coiled rattlesnake c.1300–1521

British Museum

© Trustees of The British Museum

In 1980 Moore was invited to select artworks from the British Museum collection that influenced him during his career. These objects were collated for publication in the photographic book Henry Moore at the British Museum (1981).11 After Moore’s introduction, photographs of the fifty items selected by Moore are organised according to geographical region or type. The chapter on Aztec sculpture contains five works from the museum’s collection and includes an ancient Mexican stone rattlesnake (fig.3). Moore explained why he admired this particular work, stating, ‘Although the snake is coiled into a most solid form, it has a real air of menace, as if it could strike at any moment’.12

Aztec

Serpent c.1300–1521

Stone

215 x 260 x 370 mm

British Museum

© Trustees of The British Museum

Fig.4

Aztec

Serpent c.1300–1521

British Museum

© Trustees of The British Museum

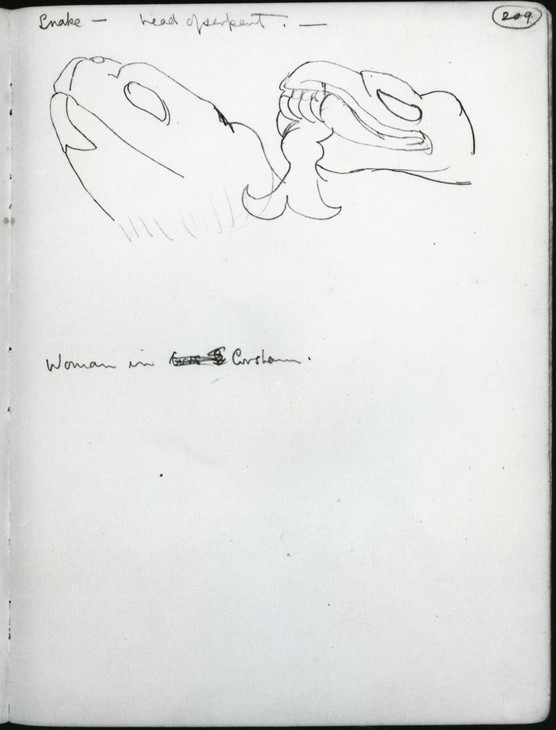

Henry Moore

Studies of a Serpent's Head 1925 (from Notebook No.3 )

Graphite on paper

224 x 172 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Studies of a Serpent's Head 1925 (from Notebook No.3 )

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Although he singled out the coiled rattlesnake for inclusion in his 1981 publication, it is likely that Moore also looked at other examples of ancient Mexican snakes in the British Museum during the 1920s. Of the entwined snakes in his 1921–2 sketch, the example on the far left appears to have more in common with the stone serpent (fig.4) than with the coiled rattlesnake. In 1996 Moore’s niece, Ann Garrould, noted that the exact source of a sketch from 1925, annotated ‘snake – head of serpent’ (fig.5), had not yet been identified, but recounted how Moore had called it ‘a bit Mexican’.13 The sketch shows two snake heads that recall both the coiled rattlesnake showing its fangs and the reposed but menacing stone example. In his sketches Moore probably amalgamated shapes seen in a range of ancient Mexican examples. With the knowledge of form that these sketches provided, Moore went on to create his own interpretations of ancient snake forms. Indeed, in Herbert Read’s 1934 publication Henry Moore: Sculptor, Moore is quoted as saying, ‘in my sculpture I do not use my memory or observations of a particular object, but rather whatever comes up from my general fund of knowledge’.14 According to Read, Moore’s animal sculptures from the 1920s were reduced to certain basic shapes or features in an attempt to convey the animal’s life force or inner character.15 In so-called primitive art, including archaic Egyptian and ancient Mexican sculpture, Read explained:

there is no attempt to conform with the exact but casual appearances of animals; and no desire to evolve an ideal type of animal. Rather from an intense awareness of the nature of the animal, its movements and its habits, the [ancient] artist is able to select just those features which best denote its vitality, and by exaggerating these and distorting them until they cohere in some significant rhythm and shape, he produces a representation which conveys to us the very essence of the animal.16

Later Moore echoed this interpretation when he praised Mexican sculpture for ‘its tremendous power without loss of sensitiveness, its astonishing variety and fertility of form invention’.17 He also found in it parallels with medieval church carvings, noting: ‘Mexican sculpture, as soon as I found it, seemed to me true and right, perhaps because I at once hit on similarities in it with some eleventh-century carvings I had seen as a boy on Yorkshire churches.’18 In 2002 Moore scholar Alan Wilkinson claimed that in his statement Moore was ‘almost certainly referring to the carved corbels’ depicting grotesque human and animal forms, thought to date from the mid-fourteenth century, in St Oswald’s Church, Methley, West Yorkshire.19 Some years earlier, W.J. Strachan had offered a similar insight, writing that Head of Serpent was ‘angled like a gargoyle and as menacing as many of them are’.20

Detail of Quetzalcoatl from the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, Teotihuacán, Mexico, c.150–200

Fig.6

Detail of Quetzalcoatl from the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, Teotihuacán, Mexico, c.150–200

Henry Moore and Rufino Tamayo at the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, Xochicalco, Mexico, 1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore and Rufino Tamayo at the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, Xochicalco, Mexico, 1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Bird 1927

Bronze

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Bird 1927

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Duck 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Duck 1927

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Inspired, perhaps, by the example of Quetzalcoatl and the ‘form invention’ of ancient Mexican sculpture, in 1927 Moore made a number of animal sculptures that only loosely resemble their subjects. Moore’s bronze Bird 1927 (fig.8) and concrete Duck 1927 (fig.9) share some similarities with Head of Serpent, in particular the angled, thrusting head.

Head of Serpent was included in Moore’s first solo exhibition held at the Warren Gallery, London, in 1928; the show included forty-two sculptures and fifty-one drawings. The Warren Gallery was run by Dorothy Warren who, in 1961, Moore remembered as ‘a remarkable person with tremendous energy and real verve, real flair’.28 Moore’s exhibition was one in a series that presented the work of artists whose fathers had been miners. The series started with a sell-out exhibition of paintings by Evan Walters (1893–1951) and concluded with a controversial display of paintings by D.H. Lawrence, which were seized by the police.29 Moore went on to recall that, although several sculptures were sold during the exhibition, it was his drawings that proved to be most successful commercially.30

Although he had exhibited in a number of group exhibitions during the 1920s, Moore’s 1928 solo exhibition put him in the public eye. Although some reviews were negative, most concurred that Moore was a young artist with potential. The unnamed reviewer for the Times claimed that although Moore’s abilities as a carver were not in question, ‘his actual sense of form is not yet highly developed’.31 One of the most positive reviews came from the Yorkshire Evening Post, although the reviewer approached the exhibition from a very particular perspective: under the title ‘Yorkshire Miner’s Artist-Son: Unconventional Work by Castleford Man’, the unnamed London correspondent for the Yorkshire Evening Post made Moore’s origins the key to understanding the exhibition. ‘Mr. Moore’s sculptures and drawings are full of primitive vitality which derives in some degree from the sturdy mining stock from which the artist springs.’32 Building on this notion that Moore’s art originated from his father’s occupation, the reviewer went on to suggest that his sculptures ‘radiate vitality and masculine strength’.33 While other reviewers focused attention on Moore’s female figures, the correspondent for the Yorkshire Evening Post highlighted Snake 1924 and Head of Serpent: ‘a snake in white marble is a striking piece of work, and the sculptor has achieved success in another study of a snake’s head in stone’.34

Perhaps the most important review of the exhibition, however, was written by P.G. Konody for the Observer.35 Konody’s review noted that there was nothing in Moore’s exhibition to suggest that he was the product of the Royal College of Art, or that he had studied under Professor Derwent Wood, whose teaching was based in the classical tradition. Positioning Moore alongside continental cubist sculptors Ossip Zadkine (1890–1967) and Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964), Konody suggested that his work was ‘more concerned with abstract relations of plane to plane than with representation’.36 Although Head of Serpent was not specifically mentioned in his review, it is possible to argue that in light of Konody’s commentary the sculpture would have been understood as a particularly modern work by those sympathetic to contemporary developments in art because of its streamlined forms.

Head of Serpent was acquired by Moore’s sister Mrs Mary Spencer Garrould sometime prior to 1944, when her ownership of the sculpture was noted in Herbert Read’s book Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings. It remains in a private collection and has been on loan to Tate since 1994.

Alice Correia

November 2012

Notes

Henry Moore cited in Carl Tucker, ‘Creators on Creating: Henry Moore’, Saturday Review, March 1981, p.44, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.223.

In the early 1970s Moore reviewed his drawings and sketchbooks with student Alan Wilkinson, who completed his doctorial thesis ‘The Drawings of Henry Moore’ (Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London) in 1974. The dates of drawings and sketches included in Wilkinson’s thesis were attributed in collaboration with Moore. Wilkinson subsequently became a leading Moore scholar and the first curator of the Henry Moore Centre at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada. Although Wilkinson’s thesis remained unpublished until 1984, much of his research was utilised in the 1978 Tate exhibition catalogue The Drawings of Henry Moore, which dated Notebook No.2 to 1921–2.

There are no recorded statements by Moore about Head of Serpent and it was rarely exhibited during his lifetime. Due to its limited exposure in exhibitions it has received very little critical attention to date. However, existing scholarship concurs that it sprung from the same sources identified in relation to the 1924 Snake, specifically Moore’s interest in ancient Mexican art. See Strachan 1983, p.23, and Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art and the Post-Columbian World, New York 2000, p.140.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeny, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.44.

Braun 2000, p.96. Braun notes that public interest in ancient Mexico had been fuelled since 1923 by regular features in the London Illustrated News.

For reports on these excavations see Anon., ‘Ruins in British Honduras’, Times, 12 January 1926, p.11, and Anon., ‘More Mayan Ruins Discovered’, Times, 10 February 1926, p.13.

In his introduction to the book Moore noted, ‘It has been a wonderful experience for me to recapture the delight, the excitement, the inspiration I got in these pieces as a young and developing sculptor’. See Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981, p.16.

Henry Moore, ‘Primitive Art’, Listener, 24 April 1941, pp.589–9, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.104.

For further information on Teotihuacán, see http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/414 , accessed 30 July 2012.

See William York Tindall, ‘D.H. Lawrence and the Primitive’, in Sewanee Review, vol.45, no.2, April–June 1937, p.203.

In 1960 Moore stated that he ‘read the whole of D.H. Lawrence’ between the ages of twenty and twenty-two (between 1918 and 1920). See Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.50.

For further information on Xochicalco, see http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/939 , accessed 22 November 2012.

Henry Moore cited in John and Vera Russell, ‘Conversations with Henry Moore’, Sunday Times, 24 December 1961, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.54.

See Alexander Davis, ‘Henry Moore’s Library: A Commentary’, in Alexander Davis (ed.), Henry Moore Bibliography. Volume 5: Index 1986–1991, Much Hadham 1994, p.89.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and Direct Carving: Technique, Concept, Context Sarah Victoria Turner

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore and Stone: Methods and Materials Sebastiano Barassi and James Copper

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Head of Serpent 1927 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www