Robert Bevan 1865–1925

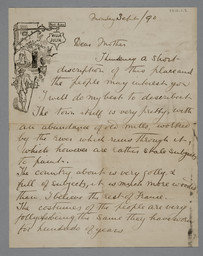

Robert Polhill Bevan (figs.1 and 2) was the fourth child in a family of six born to Richard Bevan, banker in the firm of Barclay, Bevan, Tritton and Co. (now known simply as Barclays) and Laura Bevan (née Polhill). He resisted following his elder brothers into a career in the bank and having received drawing lessons at home with the artist Arthur Earnest Pearce (1859–1934), who later became a designer for Doulton’s potteries, he studied art at the Westminster School of Art under the principalship of Frederick Brown (1851–1941), founder member of the New English Art Club and later to become Professor of the Slade School of Fine Art. Although his upbringing was quintessentially English, Bevan formed important links with the continental avant-garde from early on in his artistic career. In the autumn of 1889, he undertook a year’s study at the Académie Julian, one of many Parisian establishments that catered for art students from all over Europe. It was in Paris that Bevan was introduced to recent developments in French painting including the work of the ‘Pont-Aven School’, a colony of artists working in Brittany with Paul Gauguin. From the summer of 1890 until the autumn of 1891 Bevan visited Pont-Aven himself. His sketchbooks from this period are now in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

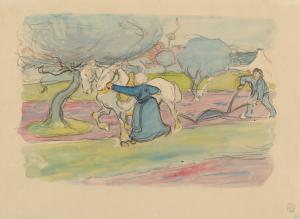

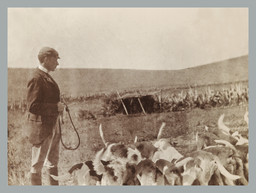

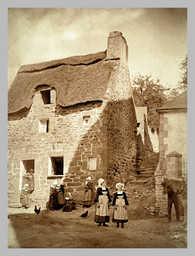

Financial support from his father initially freed Bevan from the necessity of earning a living and during his twenties he enjoyed a comfortable life indulging his two passions, painting and hunting. At the end of 1891 in the company of another artist, Joseph Crawhall (1861–1913), he travelled to Spain and then on to Tangier, Morocco, where he did not complete much work but principally enjoyed the fox hunting and racing season, acting as Master of the Hunt in 1892. From 1893–4 he returned to Pont-Aven, during which time he met both Gauguin and Renoir, and became interested in lithography. On his return to England he lived a solitary existence on an isolated farmhouse at Hawkridge, Exmoor. For the next three years he divided his time between painting and hunting, combining the two in oils, watercolours or lithographs of agricultural landscapes and hunting scenes. In July 1897 he met and fell in love with a Polish painter, Stanislawa de Karlowska, at a friend’s wedding in Jersey. After a brief but frequent correspondence,1 conducted in French, their only common language, Bevan made the journey to Poland and the two were married in Warsaw in December. They returned to Bevan’s parents’ house, Horsgate, in Cuckfield in Sussex (fig.3), where their first child, Edith Halina, ‘Halszka’, was born in December 1898. A son, Robert Alexander, ‘Bobby’, followed in March 1901.

Financial support from his father initially freed Bevan from the necessity of earning a living and during his twenties he enjoyed a comfortable life indulging his two passions, painting and hunting. At the end of 1891 in the company of another artist, Joseph Crawhall (1861–1913), he travelled to Spain and then on to Tangier, Morocco, where he did not complete much work but principally enjoyed the fox hunting and racing season, acting as Master of the Hunt in 1892. From 1893–4 he returned to Pont-Aven, during which time he met both Gauguin and Renoir, and became interested in lithography. On his return to England he lived a solitary existence on an isolated farmhouse at Hawkridge, Exmoor. For the next three years he divided his time between painting and hunting, combining the two in oils, watercolours or lithographs of agricultural landscapes and hunting scenes. In July 1897 he met and fell in love with a Polish painter, Stanislawa de Karlowska, at a friend’s wedding in Jersey. After a brief but frequent correspondence,1 conducted in French, their only common language, Bevan made the journey to Poland and the two were married in Warsaw in December. They returned to Bevan’s parents’ house, Horsgate, in Cuckfield in Sussex (fig.3), where their first child, Edith Halina, ‘Halszka’, was born in December 1898. A son, Robert Alexander, ‘Bobby’, followed in March 1901.

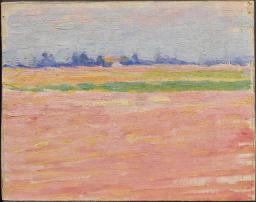

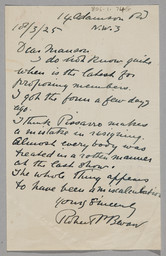

In 1900, Bevan and his family moved to a large house at 14 Adamson Road, in the Swiss Cottage area of London. Although he abandoned the paintings and lithographs of hunting scenes and never hunted again after his marriage, he still drew inspiration for subjects for painting from the countryside. He formed the habit of spending the summer on a painting trip in various rural locations such as a cottage called St Ives in Kingston near Lewes, Sussex (fig.4), or in Russian Poland with his wife’s family. His work at this time reflected his first-hand experience with recent French art during his travels on the continent. Oil paintings and watercolours of agricultural scenes of the South Downs or Poland provided motifs with which to explore his concerns with the effects of light and the use of colour. Philip Hendy (later Director of the National Gallery) claimed that Bevan was the first Englishman to use pure colour in the twentieth century and was the ‘real pioneer’ of the modern English school.2 Some indication of the progressive nature of Bevan’s early paintings can be gauged by the newspaper reviews of his first solo exhibition held at the Baillie Gallery in 1905. Bevan’s show, which featured recent Polish work, appeared five years before Roger Fry’s first post-impressionist exhibition, when the most avant-garde paintings seen in London would have been those of Claude Monet and the impressionists. The critics were unprepared for Bevan’s application of neo- and post-impressionist principles. They vilified his use of ‘violent’ and ‘garish’ colour ‘which has an evil habit of losing control over itself’,3 calling it ‘uncompromising’ and ‘French impressionism gone to the bad’.4

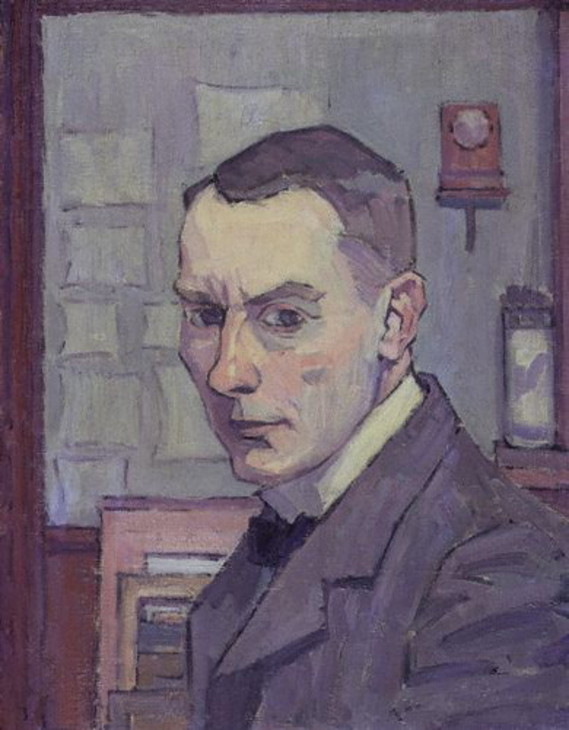

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Self-Portrait c.1914

Oil on canvas

457 x 356 mm

National Portrait Gallery, London

Photo © National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig.2

Robert Bevan

Self-Portrait c.1914

National Portrait Gallery, London

Photo © National Portrait Gallery, London

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Maples at Cuckfield, Sussex 1914

Oil paint on canvas

515 x 612 mm

National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

Photo © National Museum of Wales

Fig.3

Robert Bevan

Maples at Cuckfield, Sussex 1914

National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

Photo © National Museum of Wales

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

In the Downs near Lewes 1906

Oil paint on canvas

340 x 460 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.4

Robert Bevan

In the Downs near Lewes 1906

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

In 1900, Bevan and his family moved to a large house at 14 Adamson Road, in the Swiss Cottage area of London. Although he abandoned the paintings and lithographs of hunting scenes and never hunted again after his marriage, he still drew inspiration for subjects for painting from the countryside. He formed the habit of spending the summer on a painting trip in various rural locations such as a cottage called St Ives in Kingston near Lewes, Sussex (fig.4), or in Russian Poland with his wife’s family. His work at this time reflected his first-hand experience with recent French art during his travels on the continent. Oil paintings and watercolours of agricultural scenes of the South Downs or Poland provided motifs with which to explore his concerns with the effects of light and the use of colour. Philip Hendy (later Director of the National Gallery) claimed that Bevan was the first Englishman to use pure colour in the twentieth century and was the ‘real pioneer’ of the modern English school.2 Some indication of the progressive nature of Bevan’s early paintings can be gauged by the newspaper reviews of his first solo exhibition held at the Baillie Gallery in 1905. Bevan’s show, which featured recent Polish work, appeared five years before Roger Fry’s first post-impressionist exhibition, when the most avant-garde paintings seen in London would have been those of Claude Monet and the impressionists. The critics were unprepared for Bevan’s application of neo- and post-impressionist principles. They vilified his use of ‘violent’ and ‘garish’ colour ‘which has an evil habit of losing control over itself’,3 calling it ‘uncompromising’ and ‘French impressionism gone to the bad’.4

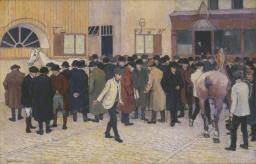

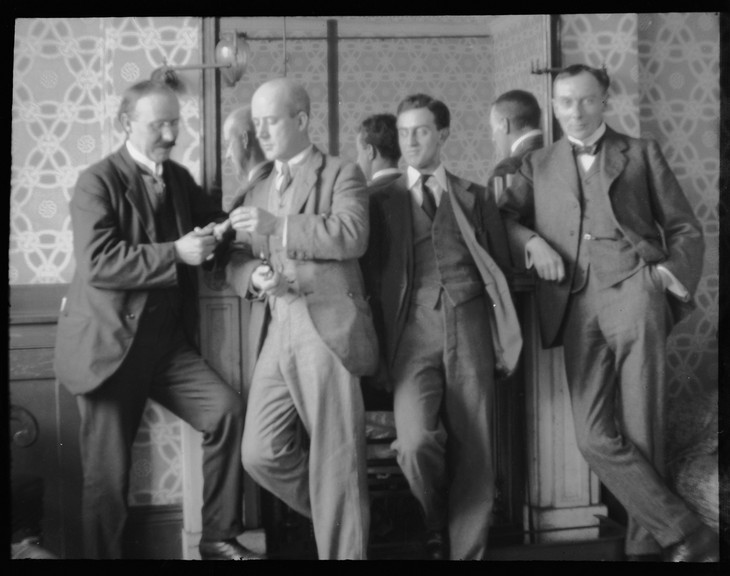

Bevan became involved with other British modernist artists relatively late in life. After the time spent abroad in France and Poland he worked largely in isolation and without recourse to a like-minded circle of artists. This all changed when in 1908 he was drawn into the artistic scene in London after exhibiting work at the inaugural exhibition of the Allied Artists’ Association. Bevan’s paintings caught the attention of Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore and they invited him to join Walter Sickert’s Fitzroy Street circle where he became a regular visitor. Although, at forty-three years of age, Bevan was over ten years older than Gore, Gilman and Charles Ginner, he was of a similar age to Sickert and Lucien Pissarro. Like the two older painters, he brought first-hand knowledge of modern French art to the group, having been one of the few Englishmen to have personally known and worked with Gauguin. In 1910 Bevan exhibited for the first time at the New English Art Club and in the following years was heavily involved in the formation and exhibitions of the Camden Town Group. His involvement with Sickert’s circle began to be reflected in observations of everyday life from the Swiss Cottage area in which he lived. It was possibly Sickert who advised Bevan to exploit his love of horses in his work and it is these paintings of working horses in the cab and sale yards of Edwardian London for which Bevan is best remembered.

Alvin Langdon Coburn 1882–1966

The Cumberland Market Group c.1915 from left to right: Charles Ginner, Harold Gilman, John Nash and Robert Bevan

Negative, gelatine on nitrocellulose roll film

90 x 120 mm

Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Fig.5

Alvin Langdon Coburn

The Cumberland Market Group c.1915 from left to right: Charles Ginner, Harold Gilman, John Nash and Robert Bevan

Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Robert Bevan sketching, possibly on the Blackdown Hills, Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.6

Robert Bevan sketching, possibly on the Blackdown Hills, Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

The Cabyard, Night 1910

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 690 mm

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Fig.7

Robert Bevan

The Cabyard, Night 1910

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Despite the fact that Bevan’s work received the praise and support of critics such as Frank Rutter, J.B. Manson and Philip Hendy, he did not sell many paintings in his own lifetime. Only one work was bought by a public art collection whilst he was alive, Cab Yard at Night 1910 (fig.7). After his death his work was vigorously promoted and exhibited by his son, Robert A. Bevan, who also completed the first comprehensive biography of his father in 1965.

Notes

Catalogue entries

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Robert Bevan 1865–1925’, artist biography, February 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www