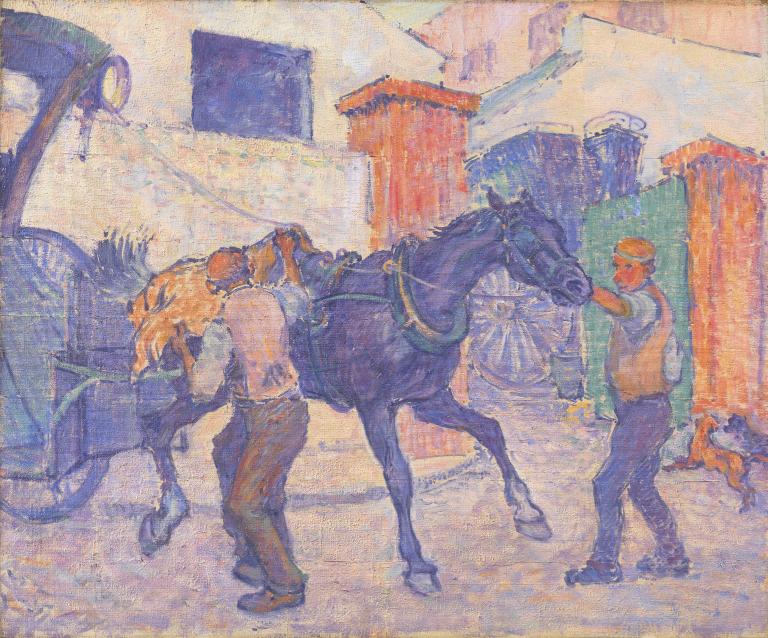

Robert Bevan The Cab Horse c.1910

Robert Bevan,

The Cab Horse

c.1910

Remarkable for its unexpected use of bright colour, Robert Bevan’s The Cab Horse was developed from studies of the cab yard at Ormonde Terrace in North London. When it was painted, motor taxis already outnumbered horse-drawn hansom-cabs in London, and the horse was disappearing from the urban landscape.

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

The Cab Horse

c.1910

Oil paint on canvas

629 x 762 mm

Presented by the Trustees of the Duveen Paintings Fund 1949

N05911

c.1910

Oil paint on canvas

629 x 762 mm

Presented by the Trustees of the Duveen Paintings Fund 1949

N05911

Ownership history

Inherited by Stanislawa de Karlowska (1876–1952), the artist’s widow; purchased through the Goupil Gallery, London, by the Duveen Paintings Fund 1926, by whom presented to Tate Gallery 1949.

Exhibition history

1910

Forty-Fourth Exhibition of Modern Pictures by the New English Art Club, Galleries of the Royal Society of British Artists, London, November–December 1910 (91).

1911

The First Exhibition of the Camden Town Group, Carfax Gallery, London, June 1911 (29).

1913

?Robert Polhill Bevan: Paintings and Drawings, Carfax Gallery, London, April 1913 (38, as ‘Putting To’).

1926

Robert Bevan: Memorial Exhibition, Goupil Gallery, London, February 1926 (129, as ‘The Cabhorse’, reproduced).

1939

Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Members of the Camden Town Group and Associated Artists, Aberdeen Art Gallery, September–October 1939 (2).

1976

Camden Town Recalled, Fine Art Society, London, October–November 1976, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, November–December 1976 (8, as ‘The Cab Horse (Putting To)’).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (15, reproduced).

2008–9

A Countryman in Town: Robert Bevan and the Cumberland Market Group, Southampton City Art Gallery, September–December 2008, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, January–March 2009 (no number, reproduced pl.8).

References

1910

Frank Rutter, ‘Round the Galleries: New English Art Club’, Sunday Times, 27 November 1910, p.2.

1911

‘The Camden Wonders’, Morning Post, 3 June 1911.

1911

A., ‘An Art Experiment. Exhibition of the New “Camden Town Group.”’, Daily Graphic, 15 June 1911, p.19.

1911

‘“Art Anarchists.” Exhibition of Pictures by the Camden Town Group’, Morning Leader, 15 June 1911.

1911

Frank Rutter, ‘Round the Galleries: Neo-Romanticists?’, Sunday Times, 25 June 1911, p.5.

1911

‘The Camden Town Group’, The Bazaar, the Exchange and Mart, 30 June 1911, p.1319.

1911

Desmond MacCarthy, ‘Mr. Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group’, Eye-Witness, 6 July 1911, p.84.

1926

‘The Goupil Gallery’, Times, 4 February 1926.

1926

Frank Rutter, ‘The Art of Robert Bevan’, Sunday Times, 7 February 1926.

1926

‘The Late Robert Bevan’, Observer, 14 February 1926.

1926

Ywain, ‘Three Hopes of English Art’, Referee, 14 February 1926.

1926

‘The Robert Bevan Memorial Exhibition’, Colour, March 1926.

1926

‘Helping Young Artists’, Evening Standard, March 1926.

1926

‘Art of the Day in the London Galleries’, Sphere, 27 March 1926, p.415, reproduced.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, p.55, reproduced pl.ix.

1965

R.A. Bevan, Robert Bevan 1865–1925: A Memoir by his Son, London 1965, pp.17, 27, reproduced pl.31 (as ‘The Cab Horse (Putting to)’).

1970

William Gaunt, ‘Robert Bevan’, British Racehorse, December 1970, p.568.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.218, 363, reproduced. pl.75.

1999

Frances Stenlake, From Cuckfield to Camden Town: The Story of Artist Robert Bevan, Cuckfield 1999, pp.37, 39, 55, reproduced p.37.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.163.

2007

Robert Upstone, ‘The London Context and Critical Reception of Robert Bevan’s “The Cab Horse”’, Burlington Magazine, vol.149, no.1255, October 2007, pp.689–93, reproduced p.691.

2008

Frances Stenlake, Robert Bevan: From Gauguin to Camden Town, London 2008, pp.91, 185, reproduced p.90.

2011

Helena Bonett, ‘“In these English farms, if anywhere, one might see life steadily and see it whole”: Representations of the Countryside in E.M. Forster’s “Howards End” and the Paintings of Robert Bevan’, The Camden Town Group, Tate 2011, http://www.tate.org.uk/.

Technique and condition

The Cab Horse is painted in artists’ oil colours on a primed and stretched canvas. The cloth is one piece of open, plain weave, coarse fibre canvas, possibly jute. The canvas warp is horizontal to the image and the top edge has distortions and holes from the hooks used to attach the canvas onto a loom for priming. The priming appears to consist of an animal glue sizing with an off-white layer of oil priming that covers most of the canvas with an even and thin layer retaining the weave texture. The Bevan studio stamp has been applied to the back of the canvas and the stretcher (see also Tate T01121).

The painting covers the whole face of the stretched canvas. The canvas was prepared for transferring the image from a drawing by forming a grid of thin threads over the front held by pins around the edges. The pin holes are approximately 3 inches apart on the vertical edge and more than 3½ inches apart along the horizontal edge forming a 7 x 7 inch grid. The grid appears to have remained in place during painting, leaving occasional characteristic ridges in the paint.

The initial drawing was applied fluently in thinned blue oil paint. Spencer Gore used the same technique for underdrawing, which was probably influenced by post-impressionist practice (see Tate T02260). The main colour was applied in rapid brushstrokes of fluid colour dabbed, scumbled and dragged on. The white priming is often visible through the broken colour, particularly in the depiction of the pale surfaces of the road and buildings. The lively texture and broken colour gives the sensation of the play of diffuse light on static and moving surfaces. Where the colour has been more extensively worked, for example in the horse, in the modification of the cab lamp and the surrounding wall towards the top left, the paint is overlaid in fluent strokes of contrasting cool and warm colours, which maintain the vibrancy of the surface. In some areas thicker applications of the fluid paint has developed fine contraction cracks on drying.

A warm yellow varnish covers most but not the entire surface. It has gathered into small pools in the intricate texture of the paint surface and was probably applied soon after the paint dried to enrich the sunken surface of the paint. There are some sizeable areas where the surface is unvarnished, which appear to be random (see also Tate N04750).

Roy Perry

November 2003

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', November 2003, in Robert Upstone, ‘The Cab Horse c.1910 by Robert Bevan’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

In 1908 Robert Bevan held a second solo exhibition at the Baillie Gallery in London, but it was barely mentioned in the press. That same year, however, brought a turning point in his career with his decision to exhibit at the inaugural exhibition at the Royal Albert Hall in July of the Allied Artists’ Association. This was an exhibiting society formed by the critic Frank Rutter on the model of the Paris Salon d’Automne which, unlike the Royal Academy, did not vet the works submitted. Instead, for a subscription, artists could simply exhibit a fixed number of works. Although the first, vast exhibition consisted of over 4,000 items, each artist’s pictures were shown as a group together. The five pictures Bevan submitted cannot now be identified. But they were admired by Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman, neither of whom had seen his work before, and they invited Bevan to join the Fitzroy Street Group. This was an important development for Bevan. For the first time since his days in Pont-Aven in Brittany, fourteen years earlier, he was part of a group of painters with shared interests. Perhaps more fundamentally, he was also given an opportunity to sell his work, and for it to be seen by important collectors and critics of contemporary British art.

Bevan was one of the older members of the group, and he seems to have quickly taken up a distinct position at Fitzroy Street. His friend Walter Bayes, another recruit from the Allied Artists’ Association exhibition, recalled that:

Bevan was rather the Mæcenas of the group whose subscription was always paid to date, and he was, I fancy, sometimes a help in time of trouble. His gruff voice and appearance of a fox-hunting squire was rather refreshing at Fitzroy Street, where some (of the visitors rather than the members) tended to be ‘arty.’ When respectable American ladies who were seeing ‘Yurrup’ came to Fitzroy Street, it was Bevan who used to fish out for display to them Gilman’s most realistic and intimate nudes.1

Bevan’s allowance from his parents allowed him to buy his friends’ work, effectively subsidising their own careers in a modest way, and formed the basis of the collection that was displayed in 2008 at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.2 His son estimated that:

At no time until his father died in 1918 did Bevan have an allowance from him greater than £300 a year. His investment income did not exceed £50 a year ... This was not the unrelieved poverty of many of his artist friends. Bevan was never forced to supplement his income by teaching like Gilman, or taking administrative posts like Hubert Wellington and Manson.3

Marjorie Lilly gave a flavour of Bevan’s personality at Fitzroy Street, recalling that:

He used to take up his stances at our parties by the chimney piece, having arranged his glass of beer and smoking apparatus on the shelf with deliberation. From this advantageous position he could observe in the looking glass before him every newcomer who entered the door. Bevan was no equalitarian, and Fitzroy Street at this time was full of gate-crashers who descended like locusts ... to consume as much as possible of the food and drink ... he subjected each guest to a prolonged glare, to assure himself that they were presentable. Sometimes, when he was doubtful of their respectability, he would question us loudly about them in his own peculiar brand of Anglo-French, much to their joy if they happened to understand him.4

Cab-yard scenes

It was probably in the same year he joined the Fitzroy Street Group that Bevan painted The Hansom Cab,5 the first of what was to become a series of pictures depicting cab-yards and their horses. Bevan’s son believed the decision to take up these subjects may have been ‘The only influence which I think Sickert exerted ... by encouraging him to paint what really interested him in what he saw around him in London’.6 This was fairly standard realist advice. A keen rider and equine connoisseur, what always interested Bevan more than anything else was horses. It should be no surprise then that he sought out urban, working life equestrian subjects for his art, and in truth Sickert may have had little to do with his decision to do so. Although the great majority were painted around 1910, between 1908 and 1912 Bevan painted a series of cab-horse subjects, numbering ‘at least eight’ according to his son.7 These include Crocks c.1909–10 (destroyed by the artist),8 The Cabyard, Night 1910 (fig.1), The Cab Yard, Evening c.1910 (private collection),9 Thirsty Cab Horse c.1910 (private collection),10 No.12612 exhibited 1911 (untraced),11 The Yard Gate exhibited 1911 (untraced),12 and The Clipped Horse 1911 (private collection).13 Cab subjects were clearly of importance to Bevan for it was the way he represented himself principally in the very first Camden Town Group exhibition, in which he showed Crocks, Tate’s The Cab Horse and The Yard Gate, along with a landscape, In Sussex c.1911 (private collection).14 Bevan showed the cab-yard at different times of day in his sequence of pictures, and under different lighting conditions.

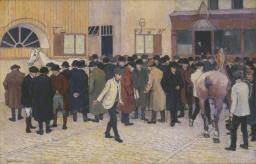

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

The Cabyard, Night 1910

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 690 mm

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Fig.1

Robert Bevan

The Cabyard, Night 1910

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

George Stubbs 1724–1806

A Grey Hunter with a Groom and a Greyhound at Creswell Crags c.1762–4

Oil paint on canvas

support: 445 x 679 mm; frame: 620 x 855 x 110 mm

Tate N01452

Purchased 1895

Fig.2

George Stubbs

A Grey Hunter with a Groom and a Greyhound at Creswell Crags c.1762–4

Tate N01452

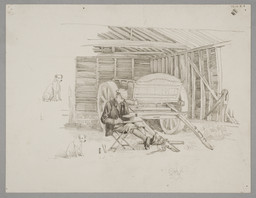

In The Cab Horse, Bevan shows a horse being released from the shafts of a two-wheeled hansom-cab, and simultaneously having a blanket thrown over its back, signifying it has returned from the day’s work. It is a scene full of movement: the horse staggering back awkwardly as the men manoeuvre it into position. The grinning face, prominent nose and lips, and ruddy colouring of the man on the right deliver an element of caricature, having something of the quality of the knockabout Georgian humour, bulging bodies and dynamic, bounding draughtsmanship of Thomas Rowlandson (1757–1827). But at the same time the man holding the bridle is also reminiscent of more elegant eighteenth-century horse and groom pictures by equestrian painters such as George Stubbs (1724–1806), for example A Grey Hunter with a Groom and a Greyhound at Creswell Crags c.1762–4 (Tate N01452, fig.2). Indeed, Bevan’s son confirms that his father ‘was a great admirer of such artists as Hogarth, Stubbs, and Rowlandson’.15 The playful dogs on the right margin add a foil or commentary to the horse’s friskiness, or the activity of the men themselves, and this also is a rhetorical device to be found in historic British painting. Bevan’s picture, however, is emphatically a scene from working-class life, and a commemoration of a working horse rather than a sleek thoroughbred. He had a lifelong love of horses, and as a young man had hunted on Exmoor and raced horses while living in Tangiers. ‘Contemporaries of his youth told us that he was a good and bold horseman’, his son wrote. ‘And though he could not afford to hunt after his marriage, and very seldom rode in England, he continued to study horses not only as types but often as individuals with love and understanding.’16

Bevan made studies for the painting at the cab-yard in Ormonde Terrace, London NW8, overlooking Primrose Hill, and just a few minutes’ walk from his house in Adamson Road, Swiss Cottage. Any trace of the cab-yard has since been obliterated by a large block of flats, probably built between the two world wars. There is an extended sequence of sketches and designs for alternative compositions at the yard in an unfoliated sketchbook in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.17 This contains numerous drawings of details of cabs, cab lamps, horses and drivers, measurements of cabs and wheels, a composition study for a view out of the Ormonde Terrace yard gates and up the road, and another of an unhitched horse and group of men lounging by the gates viewed from the same standpoint as The Cab Horse. There are not, however, in any of Bevan’s surviving sketchbooks in the Ashmolean, sketches or composition designs which directly relate to the Tate picture. The sketchbook composition studies all have a line border, indicating that Bevan considered them suitable to work up into finished pictures. Together they indicate that Bevan recorded successive stages of the cab-yard’s work, from hitching to unhitching, feeding and watering and preparation for the horse’s sleep in the stable.

Horse cabs

John Thomson 1837–1921

London Cabmen, from 'Street Life in London' 1877–8

Photograph, Woodburytype

113 x 89 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.3

John Thomson

London Cabmen, from 'Street Life in London' 1877–8

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

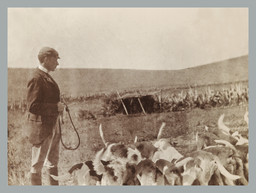

Bevan was painting his cab-horse pictures at a time of rapid transition, when the traditional cabs were being replaced by motor taxis. The horse cab trade was a big employer; the 1891 census listed 15,219 licensed London cab-drivers, and they were a more numerous group than, for instance, dock workers. There were also numerous attendant professions to the cab-drivers based in the yards themselves, such as coachbuilders and stablemen.20 The first motor cab was licensed in London in 1903, and it was the only one operating in the city that year, while there were 11,404 registered horse-drawn cabs. But over the next seven years there was a dramatic and very visible change. Bevan first showed The Cab Horse in the year that motor taxis overtook horse cabs in number. In 1909 there were 3,956 motor cabs and 6,562 horse cabs licensed and listed in the Annual Report of the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police; but in 1910 the motors became the more numerous, with 6,397 licensed against 4,724 horse cabs. This trend continued and by 1914 there were only 1,400 horse cabs; by 1923 there were 347 and in 1930 just 69, and these for the most part used for giving sight-seeing rides to tourists or for weddings.21 The look and experience of London’s streets changed irrevocably and quickly. This decline of a traditional trade caused some degree of hardship in the cab-horse business. Horse cabmen were given preferential treatment in obtaining licences to drive the new motor taxis in that they were excused being tested on their ‘knowledge’ of the streets and were simply given a driving test. In 1911 it was estimated that sixty-seven per cent of motor taxi drivers were former horse cabmen. However, others did not find replacement employment in the new trade, and older horse drivers were less likely to find a job driving motors because the cost of insuring them made their employment by the cab companies too expensive. Such was the problem that in 1910 the horse cab

drivers’ union protested that many such men were ending up in the workhouse.22 Principally as a response to the enforced retirement of the horses, but also an organisation to find work for their drivers, a Horses’ and Drivers’ Aid Committee was formed in 1912.

Bevan was evidently aware of the tribulations of the industry and the drivers. On Christmas Day 1911 he received a letter from John Lyon, Forage Contractor, of 31 Queen’s Terrace, St John’s Wood, one of the cab-yards where he had been making pictures, thanking him for what must have been a donation:

Dear Sir

Thanks very much for thinking of our stablemen again, they don’t get paid so well as they did, because the taxi cabs or new ways of getting about has about ruined our cab trade, so any kindness like yours is most acceptable to them,

With the compliments of the season23

The economics of the cab trade were explained in considerable detail in W.J. Gordon’s The Horse World of London and, although this was published in 1896, the same conditions still applied when Bevan painted The Cab Horse. Gordon explained that the horse cab trade operated on a system of rental:

Some masters drive their own cabs, and naturally take good care of their own property; but with the bulk of the cabmen the horse is a machine, hired out as one might hire out a tricycle and returned in a sufficiently sound state to avoid comment. The man finds the horse and cab ready for him in the morning; he leaves his licence as security for his return; and he drives off in search of fares. When he comes back he simply hands the cab over as it stands, pays up – or not – at the office, and hurries out of the yard. Some there are who will look over the horse before he is put into the shafts, and follow him into the stable on their return, and treat him more as a friend; but there are not many of these when we come to percentages ... The amount paid by the man for the day’s hire varies with the vehicle, the master and the season.24

Reception

Under the subheading ‘The Vanishing Cab Horse’, Frank Rutter drew attention to the contemporary resonance and social importance of Bevan’s cab pictures when they were shown in the first Camden Town Group exhibition in 1911:

I would commend to the notice of this society the works of Mr. R. P. Bevan, who is one of the hardest of the group to place by reason of his strong individuality. His decoratively conceived and shrewdly observed paintings of the vanishing cab-horse in the street and stable (28, 29, 31) are in some respects the most remarkable pictures in a remarkable exhibition. To their great and obvious artistic merits they have added a genuine historic interest, and they are precious documents of rapidly disappearing phases of London life.25

Rutter had already praised Bevan’s pictures of this sort. When The Cab Horse was shown for the first time in 1910 he had singled it out in his Sunday Times review of the New English Art Club exhibition:

The most interesting things in the show are in the two small end galleries. Here are grouped more or less together a number of works by the young painters who are reviving the fame of Fitzroy-street. Highest honours must be awarded to Mr. Robert B. [sic] Bevan for his ‘Cab Yard, Morning’ (82) and ‘The Cab Horse’ (91). Here at last is an artist who really has something to say and his own way of saying it. Obviously, he is the historian of the decline of the horse, whose character he gives with a rare half humorous tenderness. Its sorry fate he veils in half-mourning hues of violet, colour undeniably more voulu than vu, but for that reason no less expressive and harmonious. Add to these qualities a vigorous simplicity in expressing form and the power to weave forms into well-balanced and original designs, and it will be seen that in Mr. R.P. Bevan we possess a very remarkable painter with emotions to express as well the power to express them.26

The picture’s colouring was something on which almost all critical notices of The Cab Horse focused their attention. Bevan’s colour scheme was extremely adventurous, using combinations of both complementary and contrasting colours, such as red with green. His choice and use of colours is reminiscent of pictures by the Fauve painters, and may be compared most closely with those of André Derain (1880–1954). Such works were virtually unseen in London before Roger Fry’s two post-impressionist exhibitions held in 1910 and 1912. But Bevan evidently kept up with artistic developments in Paris, his son writing that:

In the years that followed their meeting, I believe that Gore, Gilman, and Bevan all had some influence on each, both in their use of colour and in their broadening of planes and masses. This was, of course, accelerated in 1910, when Gilman and Gore in London and Paris discovered the post-impressionists. But the painters who gave such a healthy shock to the London art world in Roger Fry’s post-impressionist exhibition in 1910 were not new to Bevan.27

In the first decade of the century, his son noted, Bevan ‘visited Paris from time to time and kept himself informed of what was going on across the Channel in these explosive years’.28 Postcards in the possession of Bevan’s descendants indicate that he travelled to Paris, and is likely therefore to have witnessed the progressive evolution of modern French painting, and the revolution in colouring. Bevan’s bold colour scheme, and his outlining of the forms in The Cab Horse, was probably a conscious response to recent French painting. The dabbed touches of colour are a development of the impressionist technique he had used in earlier pictures. The paint surface itself, whilst quite thin overall, has a series of ridges which suggest that it was painted using a string grid attached over the canvas. This would have been used to copy the design from a squared-up drawing on to the canvas.

The critic Desmond MacCarthy, writing in Eye-Witness, analysed whether Bevan’s colour scheme in The Cab Horse affected the essential truthfulness of the subject. ‘Among the most interesting’ items in the 1911 Camden Town exhibition, he wrote,

are three pictures by Mr. R.P Bevan. They are pictures of a cabman’s yard. In one a lean but violent screw [slang for a worn-out horse] is still between the shafts, and two ostlers drawn in energetic attitudes, one at its head the other throwing a horse rug over its quarters, are in attendance upon it; behind it is the bright green gate of the yard ... The drawing of these objects – the figures, the animals, and the cabs – is vigorous and full of animation; the colour is imaginary and fantastic. The horse between the shafts is a violet horse, the gate-pillars are an apricot red, everywhere there is an unreal iridescence, the shabby box-cloth coat of the yardmaster has a dove-like sheen on it; yet this fanciful colouring does not interfere with the realism of the scene; it seems even to enhance it, as though this convention of unnatural, bright colour succeeded in conveying a sense of the life of the stable-yard which was still an important part of our actual impression of such scenes.29

Reviewing the same show, the Morning Post decided that Bevan’s Cab Horse and The Yard Gate were

the most arresting (you can hardly avoid Scotland Yard metaphor) in design and colour ... They will undoubtedly repel you at first unless you have been through the Paris Autumn Salon cure. Then after, say ten minutes, examination of the other pictures you will realise ... that the painter has something to say, and that his horses have brought news from Ghent – ‘pleasant or unpleasant’ is beside the question [a reference to Robert Browning’s poem ‘How they Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix’(1845), which evokes the rhythm of galloping horses].30

Reactions to Bevan’s pictures in the group’s first exhibition were mixed. While The Bazaar, the Exchange and Mart observed that ‘Truly clever and impressionistic are the cab-yard scenes by Mr. R.P. Bevan’,31 the Daily Graphic sardonically noted ‘It cannot be said there is anything among the exhibits which calls for a lyrical expression of delight, unless such might be inspired by a company of ballet dancers, cab horses, and murderers, to which Mr. Gore, Mr. Bevan and Mr. Sickert introduce us’.32 The Morning Leader, under the heading ‘Art Anarchists’, felt it necessary to warn visitors:

Certain pictures, the ‘Crocks’ and ‘Cab Horse’ of Mr. R.P. Bevan, for instance, will come as a shock to those accustomed to traditional methods. Mr. Bevan’s work at first sight looks as if a naughty child had run amok with a box of crayons and a badly illustrated paper ... for looking at a few of the pictures in the exhibition smoked glasses are almost a necessity.33

Huntly Carter in the New Age had identified what he perceived as a small group of ‘colourists’ within the 1910 New English Art Club exhibition at which The Cab Horse was shown. After postulating that ‘colour has the rare merit of changing men’s atmosphere’, he observed that while colour had the potential to enervate it could also be a source of disturbance, and that ‘three fourths of the human race are unaffected by colour, except in a hostile form. Pure, clean colour arouses in their honest bosoms an exasperation only equalled by that called forth by the so-called indecent forms of art.’34 Turning to the New English Art Club exhibition, Carter continued:

The successful praise of colour, which is one of the highest achievements in painting, has been undertaken and accomplished by a small group of painters. Within this group there is another small group composed of painters who intimately understand the colour of colour and the colour of shadows. One who has mastered this knowledge is S.F. Gore ... Another is Lucien Pissarro, who is carrying on the brilliant traditions of his father .... Robert Bevan is a third colourist belonging to this individual group. Here, again, in his work are clear vision and clever interpretation, light and colour treated reverently and handled sincerely, and with full understanding ... A fourth is Harold Gilman ... I have grouped these four painters because their work has characteristics in common. They do not seek to uphold the academic traditions of the N.E.A.C. ... They conceive and express subject in colour; they work putting the colour on in separate touches all through; they use very simple palettes and make very simple mixtures. They avoid the use of varnishes; their surfaces are, in consequence, matt, and thus their work largely partakes of the character of early tempera.35

When Bevan showed The Cab Horse at the 1910 winter exhibition of the New English Art Club, he and the other Fitzroy Street artists were getting increasingly irritated with the club’s selectors, and two of Bevan’s watercolours were turned down for the show. Spencer Gore wrote about the exhibition to his pupil John Doman Turner:

Your drawings looked very distinguished when they came up at the NEAC. Unfortunately the most conventional minded of a set of people whose ideas of painting are about 50 years out of date hung the watercolours of Rich!!!36 As you know from his work which is entirely imitative and has not an atom of observation in it ... Also you may notice that we – myself, Pissarro, Gilman, Bevan, Lamb have all been gently pushed into the inner rooms. Gilman had one thing rejected and Bevan two watercolours while Innes another interesting artist has all his watercolours very badly hung.37

This dissatisfaction with the New English Art Club would be one of the factors that precipitated the founding of the Camden Town Group in 1911. In his next letter to Doman Turner, Gore wrote baldly:

As to where things are hung it means nothing except that the NEAC dislike our kind of painting and will probably edge us out all together sooner or later and you have suffered with us.38

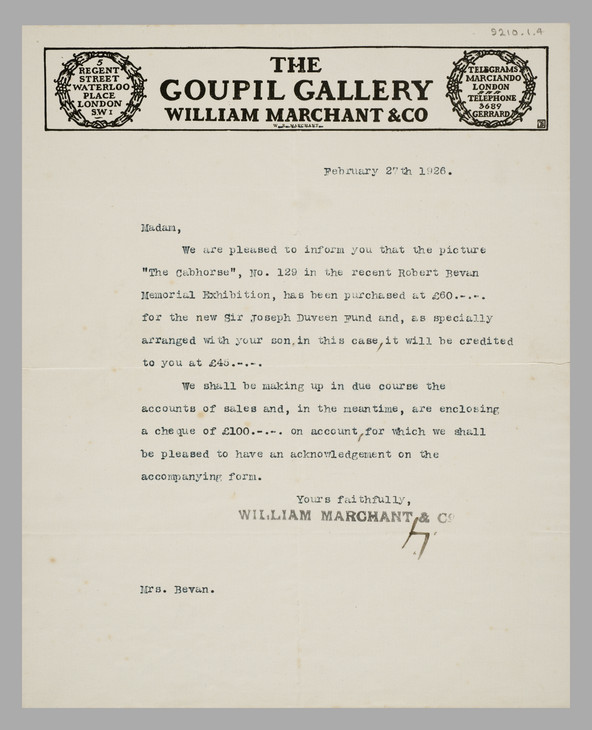

William Marchant & Co.

Letter to Stanislawa de Karlowska 27 February 1926

Tate Archive TGA 9210/1/4

William Marchant & Co.

Letter to Stanislawa de Karlowska 27 February 1926

Tate Archive TGA 9210/1/4

Following Bevan’s death a memorial exhibition was held at the Goupil Gallery in 1926 and The Cab Horse was bought there by the Duveen Fund for £60 (fig.4). The first work it had acquired, it was not assigned to the Tate Gallery until 1949.

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

See From Sickert to Gertler: Modern British Art from Boxted House, exhibition catalogue, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh 2008.

Untraced, once in the collection of Judge Evans, reproduced in Colour Magazine, July 1918, p.128. A crayon and watercolour study of the same composition is reproduced in Bevan 1965, pl.28.

Repainted in 1922, this second version reproduced in Frances Stenlake, Robert Bevan: From Gauguin to Camden Town, London 2008, p.168. The composition was also used for a lithograph Bevan made in 1924–5, reproduced in Stenlake 2008, p.169.

Shown at the 1911 Camden Town Group exhibition (32). The 3 December review in the Sunday Times confirmed it was a cab subject.

All statistics taken from Trevor May, Gondolas and Growlers: The History of the London Horse Cab, Stroud 1995, pp.v, 166.

A., ‘An Art Experiment. Exhibition of the New “Camden Town Group.”’, Daily Graphic, 15 June 1911, p.19.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related archive items

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

Related reviews and articles

- Desmond MacCarthy, ‘Mr. Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group’ Eye-Witness, 6 July 1911, pp.83–4..

- Huntly Carter, ‘Art’ The New Age, 9 June 1910, pp.135–6.

- A., ‘An Art Experiment. Exhibition of the New “Camden Town Group.”’ The Daily Graphic, 15 June 1911, p.19.

- Walter Bayes, ‘The Camden Town Group’ The Saturday Review, 25 January 1930, pp.100–1.

- Author unknown, ‘“Art Anarchists.” Exhibition of Pictures by the Camden Town Group’ Morning Leader, 15 June 1911.

- Author unknown, ‘The Camden Wonders’ Morning Post, 3 June 1911.

- Frank Rutter, ‘Round the Galleries’ Sunday Times, 25 June 1911, p.5.

- Author unknown, ‘The Camden Town Group’ The Bazaar, The Exchange and Mart, 30 June 1911, p.1319.

Related film

-

A horse-drawn carriage and horse and cart pass by the Tate Gallery, London 1910© British Pathé

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘The Cab Horse c.1910 by Robert Bevan’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www